Abstract

Background

Improving our understanding of the relationship between the genotype and the drug resistance phenotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis will aid the development of more accurate molecular diagnostics for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Studies that use direct genetic manipulation to identify the mutations that cause M. tuberculosis drug resistance are superior to associational studies in elucidating an individual mutation's contribution to the drug resistance phenotype.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the literature for publications reporting allelic exchange experiments in any of the resistance-associated M. tuberculosis genes. We included studies that introduced single point mutations using specialized linkage transduction or site-directed/in vitro mutagenesis and documented a change in the resistance phenotype.

Results

We summarize evidence supporting the causal relationship of 54 different mutations in eight genes (katG, inhA, kasA, embB, embC, rpoB, gyrA and gyrB) and one intergenic region (furA-katG) with resistance to isoniazid, the rifamycins, ethambutol and fluoroquinolones. We observed a significant role for the strain genomic background in modulating the resistance phenotype of 21 of these mutations and found examples of where the same drug resistance mutations caused varying levels of resistance to different members of the same drug class.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights those mutations that have been shown to causally change phenotypic resistance in M. tuberculosis and brings attention to a notable lack of allelic exchange data for several of the genes known to be associated with drug resistance.

Keywords: M. tuberculosis, microbial susceptibility tests, genetics, SNPs, in vitro resistance

Introduction

The 2012 WHO report on global tuberculosis (TB) surveillance suggests that only one in five patients with drug-resistant TB are diagnosed and appropriately treated.1 Patients with undiagnosed drug resistance have higher morbidity and mortality than patients with drug-susceptible disease, and may continue to spread drug-resistant TB in their communities.2 The WHO has stated that a major challenge for drug-resistant TB control is the lack of laboratory capacity to diagnose resistance.1 Newer, molecular-based diagnostics detect mutations conferring drug resistance and offer advantages for the identification of resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) over traditional culture-based techniques, including a more rapid turnaround time and a lower level of skill required to run the tests.3–5 A thorough understanding of which mutations encode drug resistance in Mtb will be helpful in focusing research aimed at elucidating the underlying mechanisms of resistance and in supporting the development of more accurate molecular diagnostic tests for patient care.

Epidemiological studies of Mtb drug resistance have largely focused on the association of specific mutations with the drug resistance phenotype, primarily through the comparison of mutations in specific genes in resistant clinical strains with drug-susceptible counterparts.6–8 This approach, however, cannot definitively establish causality between the mutation and the resistance phenotype. Studies using direct bacterial genetic manipulation to identify the mutations that cause Mtb drug resistance can better elucidate the individual mutation's contribution to the drug resistance phenotype and uncover whether additional factors, like synergy, strain background or interactions between mutations, modulate this relationship. The purpose of this systematic review is to clarify mutation–phenotype relationships in Mtb by identifying which mutations have been causally linked to Mtb drug resistance and in what context these causal observations have been made.

Methods

Definitions

Two types of mutation were included in this study: (i) non-synonymous nucleotide substitutions, denoted by x#y, where x represents the wild-type amino acid, # the codon number and y the variant amino acid; and (ii) non-coding (ribosomal RNA, promoter, intergenic regions) nucleotide substitutions, denoted by #xy, where # refers to the position relative to the start of the non-coding region, x is the wild-type nucleotide base and y is the variant nucleotide base. For phenotype measurements, we defined MIC as the lowest concentration of drug that inhibits bacterial growth and IC50 as the concentration of drug required to inhibit supercoiling activity by 50%. We describe a mutation leading to any increase in MIC as causative of resistance; mutations that increase the MIC above the accepted critical concentration for medical diagnostic testing is said to be causing clinical levels of resistance.9

Literature search

Using the search strategy described in Table 1, we identified peer-reviewed primary research studies that reported the effect of creating specific mutations in resistance-associated genes on the drug resistance phenotypes of Mtb strains. We searched the PubMed and EMBASE databases from January 1980 to June 2012, using combinations of the keywords listed in Table 1. Bibliographies of articles selected for further review were hand-searched and additional references not previously identified were added as appropriate. We performed full-text mining of keywords in search theme 4 ‘Introduction of mutation’ on articles retrieved by PubMed and EMBASE using search themes 1–3. This additional step was undertaken to capture articles that did not have these keywords in the title or abstract.

Table 1.

Search strategy to identify studies of mutations documented to confer resistance by evidence of genetic experiment

| Search theme |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. organism | 2. drug resistance | 3. mutation | 4. method of introducing mutation | |

| PubMed database | ||||

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms | 1. ‘mycobacterium tuberculosis’ | 1. ‘drug resistance’, OR | 1. ‘mutation’, OR | NA |

| 2. ‘microbial sensitivity tests’ | 2. ‘amino acid substitution’, OR | |||

| 3. ‘mutagenesis, site-directed’, OR | ||||

| 4. ‘codon’ | ||||

| text terms | 1. ‘mycobacterium tuberculosis’, OR | 1. ‘resistance’, OR | 1. ‘mutation*’, OR | 1. ‘isogenic’, OR |

| 2. ‘m tuberculosis’, OR | 2. ‘mic’, OR | 2. ‘mutagenesis’, OR | 2. ‘engineered’, OR | |

| 3. ‘mtb’ | 3. ‘inhibitory concentration’, OR | 3. ‘mutant*’, OR | 3. ‘mutagenesis’, OR | |

| 4. ‘drug susceptibility’ | 4. ‘nonsense’, OR | 4. ‘recombinant’, OR | ||

| 5. ‘missense’, OR | 5. ‘site-directed’, OR | |||

| 6. ‘frameshift’, OR | 6. ‘allelic’, OR | |||

| 7. ‘codon*’, OR | 7. ‘transduction’, OR | |||

| 8. ‘transduction’ | 8. ‘wild-type’, OR | |||

| 9. ‘induced’, OR | ||||

| 10. ‘introduced’ | ||||

| EMBASE | ||||

| Emtree tool | 1. ‘mycobacterium tuberculosis’ | 1. ‘drug resistance’ | 1. ‘mutation’, OR | NA |

| 2. ‘site-directed mutagenesis’, OR | ||||

| 3. ‘amino acid substitution’, OR | ||||

| 4. ‘codon’ | ||||

| text terms | 1. ‘mycobacterium tuberculosis’, OR | 1. ‘resistance’, OR | 1. ‘mutations*’ OR | 1. ‘isogenic’, OR |

| 2. ‘m tuberculosis’, OR | 2. ‘mic’, OR | 2. ‘mutagenesis’, OR | 2. ‘engineered’, OR | |

| 3. ‘mtb’ | 3. ‘mics’, OR | 3. ‘mutant*’, OR | 3. ‘mutagenesis’, OR | |

| 4. ‘inhibitory concentration’, OR | 4. ‘nonsense’, OR | 4. ‘recombinant’, OR | ||

| 5. ‘drug susceptibility’ | 5. ‘missense’, OR | 5. ‘site-directed’, OR | ||

| 6. ‘dst’ | 6. ‘frameshift’, OR | 6. ‘allelic’, OR | ||

| 7. ‘codon*’, OR | 7. ‘linkage transduction’, OR | |||

| 8. ‘transduction’ | 8. ‘wild-type’, OR | |||

| 9. ‘induced’, OR | ||||

| 10. ‘introduced’ | ||||

NA, not available.

Study selection criteria

Methods to investigate phenotype causation have included (i) gene knockouts and complementation of the resulting null mutants; (ii) increasing transcription of the gene, leading to its overexpression; and (iii) in vitro selection of drug-resistant clones by plating susceptible strains on serial dilutions of a drug.10–12 While the former methods shed light on whether the entire gene is essential for resistance, spontaneous mutants with a resistance phenotype may include compensatory mutations. Allelic exchange techniques, which introduce specific point mutations into a gene of interest, do not have these limitations and directly define the causative role for mutations in drug resistance, making it our method of choice for this review.

We included studies if they met the following criteria: (i) single point mutations within a putative resistance gene were introduced into Mtb strains using specialized linkage transduction or site-directed/in vitro mutagenesis; and (ii) a change in the resistance phenotype was documented. The resistance phenotypes were reported as MIC measurements or IC50 results performed before and after the introduction of a mutation. Researchers have demonstrated a quinolone structure–activity relationship for the gyrA/B protein complex, in which inhibition of supercoiling activity by 50% (IC50) correlates well (better than DNA cleavage) with inhibition of Mtb growth by the fluoroquinolones (FQs).13 We included studies that used liquid- or solid-based media for drug susceptibility testing.

We excluded manuscripts that (i) studied mycobacterial species other than Mtb; (ii) created knockout or overexpression of a gene instead of a single point mutation; (iii) did not specify the host strain used when measuring the MIC effect; (iv) did not state how the unique transfer of the intended point mutation was confirmed; or (v) did not have a phenotypic result (MIC or IC50). We excluded in vitro selected mutations in order to remove the potential effects of compensatory mutations.

Data extraction

For every study that met our eligibility criteria, two of three authors (H. N.-G., K. R. J. and M. R. F.) independently reviewed the data and one additional author (M. B. M.) adjudicated differences between the authors. From each publication, the following information was extracted by two authors (H. N.-G. and K. R. J.): authors; publication year; gene; amino acid and nucleotide coordinates of the mutation; host strain and method used to introduce the mutation; method used to confirm introduction of the mutation; resistance genotypic and phenotypic susceptibility methods; and phenotypic results. Additional details and clarifications were obtained via personal correspondence by one of the authors (H. N.-G.).

Results

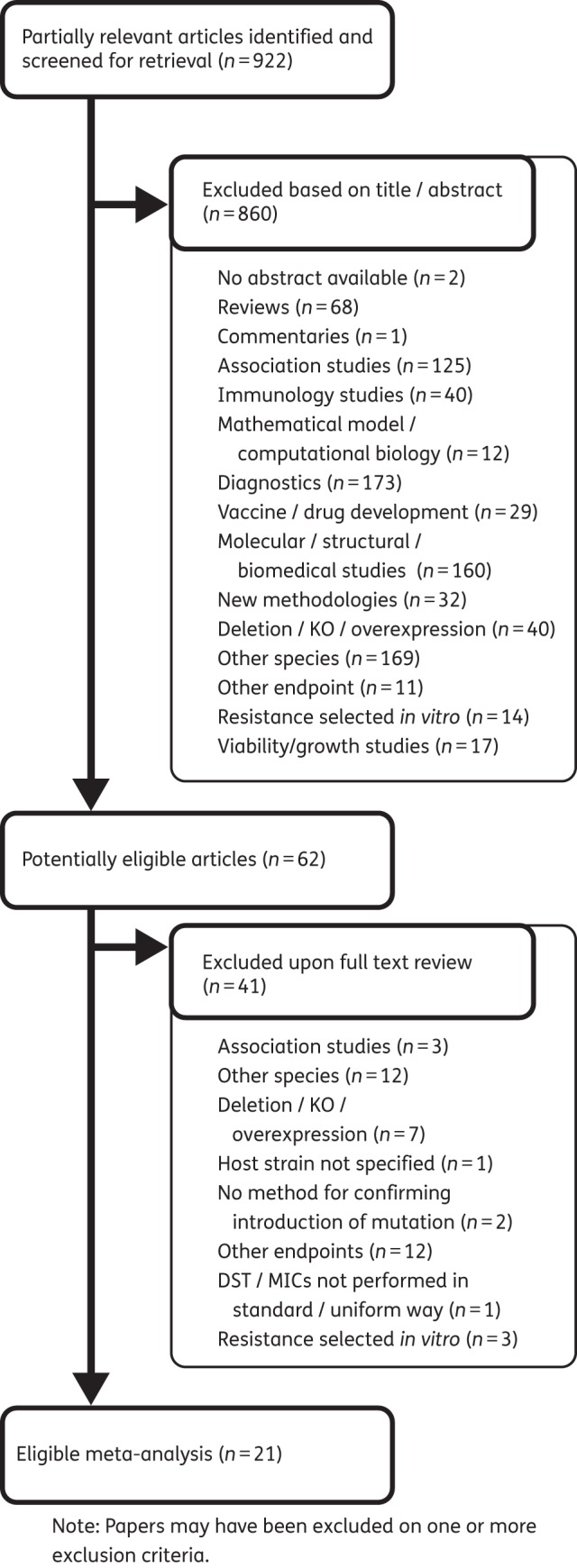

Of the 489 publications that we identified, 444 were excluded after abstract review. We performed full-text reviews of the remaining 45 papers and excluded a further 25. We identified 433 more papers through an additional text-mining step. Seventeen of these were selected through title and abstract review, but 16 were excluded upon full-text review. In total, 21 articles were selected for inclusion and final data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process and reasons for exclusion of studies. KO, knock-out.

Isoniazid

We identified studies examining 11 different putative isoniazid resistance mutations in four Mtb genes: katG, the furA-katG intergenic region, inhA and kasA. Of these 11 mutations, 7 were shown to confer resistance to isoniazid (Table 2). No two studies looked at the same point mutation.

Table 2.

Mutations shown to confer resistance to isoniazid, ethambutol or RIF

| Drug | Gene | Host strain | Substitution | MIC (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | katG | INH34a | WTb | 0.1 | Pym et al., 200214 |

| S315T | 5 | ||||

| T275P | >10 | ||||

| H37Rv | WT | 0.1 | Richardson et al., 200917 | ||

| W300G | 128 | ||||

| furA-katG intergenic region | NCGM2836c | WTb | 0.1 | Ando et al., 201118 | |

| G7A | 0.4 | ||||

| A10C | 0.4 | ||||

| G12A | 0.15 | ||||

| inhA | H37Rv | WT | 0.1 | Vilcheze et al., 200616 | |

| S94A | 0.5 | ||||

| Ethambutol | embB | 210d | WT | 2 | Safi et al., 201023 |

| G406S | 6 | ||||

| G406A | 7 | ||||

| G406D | 7 | ||||

| G406C | 7 | ||||

| Q497R | 12 | ||||

| 210d | WT | 2 | Safi et al., 200819 | ||

| M306I (ATA) | 7 | ||||

| M306I (ATC) | 7 | ||||

| M306L | 8.5 | ||||

| M306V | 14 | ||||

| 5310e | WT | 3 | |||

| M306I (ATA) | 16 | ||||

| M306I (ATC) | 16 | ||||

| M306L | 20 | ||||

| M306V | 28 | ||||

| H37Rv | WT | 1 | Plinke et al., 201121 | ||

| M306I (ATC) | 2 | ||||

| M306I (ATA) | 4 | ||||

| M306V | 4 | ||||

| H37Rv | WT | 5 | Starks et al., 200920 | ||

| M306V | 20 | ||||

| M306I (ATA) | 10 | ||||

| Beijing F2 | WT | 5 | |||

| M306V | 20 | ||||

| M306I (ATA) | 10 | ||||

| embC | H37Rv | WT | 3 | Goude et al., 200922 | |

| T270I | 4 | ||||

| Rifampicin | rpoB | H37Rv | WT | 0.25 | Williams et al., 199824 |

| D516V | 32 | ||||

| H526Y | 64 | ||||

| S531L | >64 | ||||

| WT | ≤0.015f | ||||

| H526Y | 16f | ||||

| S531L | 16f | ||||

| WT | 0.03g | ||||

| D516V | 16g | ||||

| H526Y | 16g | ||||

| S531L | >64g | ||||

| H37Ra | WT | 1.5 | Zaczek et al., 200926 | ||

| D516V | 50 | ||||

| H526Y | 25 | ||||

| S531L | 50 | ||||

| S512I + D516G | 6.2 | ||||

| Q513L | 6.2 | ||||

| M515I + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| D516Y | 3.1 | ||||

| KL1936h | WT | 1.5 | |||

| H526D | 50 | ||||

| D516V | 25 | ||||

| Q513L | 12.5 | ||||

| S531L | 50 | ||||

| Q510H + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| S512I + D516G | 6.2 | ||||

| M515I + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| KL463i | WT | 1.5 | |||

| H526D | 50 | ||||

| D516V | 25 | ||||

| Q513L | 50 | ||||

| S531L | 50 | ||||

| Q510H + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| S512I + D516G | 6.2 | ||||

| M515I + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| D516Y | 3.1 | ||||

| H37Raj | WT | 1.5 | |||

| H526D | 50 | ||||

| D516V | 25 | ||||

| S531L | 50 | ||||

| Q510H + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| S512I + D516G | 6.2 | ||||

| Q513L | 6.2 | ||||

| M515I + D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| D516Y | 6.2 | ||||

| H37Ra | WT | <0.1 | Siu et al., 201127 | ||

| S531L | 64 | ||||

| V146F | 64 | ||||

| I572F | 8–16 |

WT, wild-type.

aΔfurA-ΔkatG clinical isolate resistant to isoniazid and with inherent up-regulation of ahpC.

bComplemented with the wild-type katG gene.

cΔfurA-ΔkatG clinical isolate resistant to isoniazid.

dDrug-susceptible clinical strain, member of the W-Beijing family.

eClinical isolate resistant to ethambutol.

fRifabutin.

gRifapentine.

hRifampicin-susceptible clinical strain containing PrpoB natural promoter.

iRifampicin-susceptible clinical strain.

jContaining a modified heat shock promoter (Phsp65).

Mutations that caused isoniazid resistance

Pym et al.14 investigated two point mutations in katG using host strain INH34, a clinical isolate with inherent up-regulation of ahpC.15 The use of this strain ensured that any phenotypic differences detected among the INH34 transformants could not be due to the emergence of compensatory mutations in the promoter region of ahpC. Both katG S315T and T275P caused isoniazid resistance. Vilcheze et al.16 introduced mutation S94A into the inhA gene of an H37Rv Mtb reference strain and found that it conferred a >5-fold increase in resistance to both isoniazid and ethambutol. Richardson et al.17 demonstrated that a katG W300G H37Rv transformant caused a 1280-fold increase in isoniazid MIC, while Ando et al.18 found that complementing mutations (−7GA, −10AC and −12GA) into a clinical isolate with a deleted furA-katG gene conferred low-level isoniazid resistance (0.1–1 mg/L).

Mutations that had no effect on isoniazid resistance

Pym et al.14 complemented a resistant furA-katG deletion Mtb mutant with a katG gene carrying the A139V mutation and found that it restored isoniazid susceptibility. This demonstrates that A139V does not confer resistance in this strain. Vilcheze et al.16 found that kasA G312S and F413L mutations in H37Rv caused no detectable changes in isoniazid MIC. Ando et al.18 found that mutation C41T in furA resulted in no appreciable change in MIC relative to the Mtb strain harbouring the wild-type furA gene (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mutations shown not to confer resistance to isoniazid, ethambutol or rifampicin

| Drug | Gene | Host strain | Substitution | MIC (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | katG | INH34a | A139V | 0.1 | Pym et al., 200214 |

| furA-katG intergenic region | NCGM2836a | C41T | 0.1 | Ando et al., 201118 | |

| kasA | H37Rv | G312S | 0.1 | Vilcheze et al., 200616 | |

| F413L | 0.1 | ||||

| Ethambutol | embC | H37Rv | M300L | 0.5b | Goude et al., 200922 |

| M300I | 3 | ||||

| M300V | 0.5b | ||||

| D294G | 0.5b | ||||

| Rifampicin | rpoB | H37Rv | D516V | ≤0.015c | Williams et al., 199824 |

| H37Ra | Q510H + D516Y | 1.5 | Zaczek et al., 200926 |

aΔfurA-ΔkatG clinical isolate resistant to isoniazid and with inherent up-regulation of ahpC.

bMutations shown to increase susceptibility to isoniazid, ethambutol or rifampicin.

cRifabutin.

Ethambutol

We identified six studies examining nine different putative ethambutol resistance mutations in the gene embB. Four of these investigated the same three mutations [Met306Ile (ATA), Met306Ile (ATC) and Met306Val]. We identified one additional study that examined five putative ethambutol resistance mutations in embC. All nine embB mutations and one embC mutation were shown to confer resistance to ethambutol.

Mutations that caused ethambutol resistance

Two different clinical strains were chosen by Safi et al.19 as host backgrounds for introducing embB gene mutations into codon 306: drug-susceptible 210 belonging to the W-Beijing family, the embB sequence of which is identical to that of laboratory strain H37Rv; and the ethambutol-resistant clinical isolate 5310 that had been reverted back to wild-type embB sequence. Mutations M306V, M306L, M306I (ATA) and M306I (ATC) all caused ethambutol resistance (MIC > 4 mg/L) when incorporated into wild-type strain 210 and strain 5310.19

Starks et al.20 introduced the embB M306V allele into H37Rv and Beijing F2, resulting in a 4-fold ethambutol MIC increase, while M306I resulted in a 2-fold increase in both host strains. Plinke et al.21 found a 4-fold increase in ethambutol MIC for mutations M306V and M306I (ATA) and a 2-fold increase for mutation M306I (ATC) when introduced into H37Rv. These, however, remained below the critical clinical cut-off value. Goude et al.22 showed that mutation M70I introduced into H37Rv presented a small increase in ethambutol MIC (4 mg/L), insufficient to render it clinically resistant.

Safi et al.23 also looked at the role of common mutations found in clinical strains with high-level ethambutol resistance at the embB 406 and 497 codons. They substituted the wild-type clinical Mtb 210 strain embB G406 codon with G406A, G406D, G406C or G406S, all of which led to ethambutol resistance. Replacing the wild-type embB Q497 codon in strain 210 with the Q497R codon also increased the ethambutol MIC (Table 2).

Mutations that potentiated susceptibility or had no effect on ethambutol resistance

Goude et al.22 introduced a point mutation at the conserved aspartate D294G that had previously been shown to affect the activity of embC in Mycobacterium smegmatis to determine whether a similar effect would be seen in Mtb. They found that D294G and a further two mutations introduced into codon 300 of the embC arabinosyltransferase (M300L and M300V) increased susceptibility to ethambutol. Mutation M300I had no resistance effect (Table 3).

Rifamycins

We identified four studies that examined five putative single rifamycin resistance mutations and three double mutations in Mtb. The most common rifamycin amino acid substitutions in clinical strains (rpoB codons 531, 526 or 516) and two additional mutations were shown to individually confer resistance to rifamycins.23

Mutations that caused resistance to rifamycins

Williams et al.24 investigated the causal relationship between specific amino acid changes and three rifamycins (rifampicin, rifapentine and rifabutin) by incorporating mutations D516V, H526Y and S531L into the rpoB gene of Mtb H37Rv. Mutant alleles S531L and H526Y conferred high-level resistance to the three rifamycins (Table 2). Clones containing mutation D516V showed resistance to rifampicin and rifapentine but susceptibility to rifabutin. Gill and Garcia25 also found that these three mutant alleles led to elevation of IC50 values for rifampicin, rifabutin and rifaximin. They found that the rifabutin IC50 was elevated less by mutations S531L and D516V than by H526Y. Zaczek et al.26 explored whether the background Mtb strain affected the change in the rifampicin MIC. All strain backgrounds (H37Ra, KL1936 and KL463) containing rpoB genes with mutations H526D, D516V or S531L had high-level rifampicin resistance.

Noting that 5% of clinical strains with rifampicin resistance do not have mutations in the 81 bp region of rpoB, Siu et al.27 aimed to identify mutations located outside this rifampicin resistance-determining region. They found that H37Ra transformants containing mutations S531L or V146F were resistant to rifampicin. Transformants containing mutation I572L had a rifampicin MIC raised to 8–16 mg/L. Although V146F and I572L conferred resistance, the authors noted that they are rarely seen in clinical strains.

Zaczek et al.26 found that D516Y conferred low-level resistance in strains KL453, KL1936 and H37Ra. The double mutations Q510H + D516Y, S512I + D516G and M515I + D516Y all conferred low-level resistance in these strains. Hence, the substitutions in position 516 (D/Y; D/G), even when supported with Q510H, M515I or S512I, did not result in a large increase in the rifampicin MIC. The authors therefore concluded that a mutation D/Y or D/G at 516 is not sufficient to confer clinical rifampicin resistance in Mtb, in contrast to D/V, which does confer clinical resistance.

Mutation(s) with an effect on resistance to rifamycins that varied by host strain

Zaczek et al.26 found that mutation Q513L led to high-level rifampicin resistance in strain KL463, lower-level resistance in KL1936 and no significant increase in MIC in H37Ra (Table 2).

FQs

We identified nine articles that studied the causal relationship between mutations in gyrA/B in Mtb and resistance to FQs. All except one of these studies measured IC50 rather than MIC as the resistance outcome. Not all FQs have the same effect on Mtb. Ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin have bacteriostatic antimycobacterial activity, whereas moxifloxacin shows high bactericidal activity.25

gyrA

Mutations that caused FQ resistance

Onodera et al.28 found that gyrA mutations A90V and A90V + D94V greatly increased the IC50 of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin compared with the wild-type (Table 4). Aubry et al.29 reported that gyrA mutations A90V, D94G and D94H led to increased IC50s of four FQs; in addition, mutation A90V + D94G had an additive effect as a double mutant. Matrat et al.30 found that transformants bearing gyrA G88A and G88C were more resistant than wild-type gyrase to inhibition by FQs. The increases in IC50 for G88C were higher than for G88A with respect to gatifloxacin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin and similar for ofloxacin. Malik et al.31 reported that the A74S mutation increased the MIC 2-fold to 4-fold for each FQ tested, which is slightly above the critical concentration. While the single D94G mutation conferred resistance, the addition of A74S to D94G had a synergistic effect, further increasing the MICs of all FQs tested by 2-fold to 8-fold over those for the single D94G mutation. Kim et al.32 found that IC50 values of levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin against DNA gyrase containing S95 + D94G were 2-fold greater than those against DNA gyrase containing S95 with A74S + D94G, which was higher than the wild-type.

Table 4.

Mutations shown to cause resistance to at least one FQ

| Gene | Host straina | Substitution | Ofloxacin IC50 or MICb (mg/L) | Ciprofloxacin IC50 or MICc (mg/L) | Levofloxacin IC50 or MICd (mg/L) | Gatifloxacin IC50 or MIC (mg/L) | Moxifloxacin IC50 or MICe (mg/L) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gyrA | — | WT | — | 12.2 | 13.9 | — | — | Onodera et al., 200128 |

| A90V | — | >400 | >400 | — | — | |||

| A90V + D94V | — | >400 | >400 | — | — | |||

| — | WT | 10 | — | 12 | 2.5 | 2 | Aubry et al., 200629 | |

| A90V | 100 | — | 55 | 20 | 35 | |||

| D94G | 350 | — | 170 | 70 | 50 | |||

| D94H | 800 | — | 320 | 150 | 90 | |||

| A90V + D94G | >1600 | — | >1600 | >320 | >160 | |||

| — | WT | 10 | — | 5 | 4 | 4 | Matrat et al., 200630 | |

| G88A | 40 | — | 30 | 7 | 10 | |||

| G88C | 50 | — | 100 | >128 | 35 | |||

| — | WT (S95) | — | 18 | 34 | 9 | — | Kim et al., 201232 | |

| D94G + S95 | — | 196 | 310 | 76 | — | |||

| A74S + D94G + S95 | — | 107 | 171 | 48 | — | |||

| H37Rv or Erdman | WT | 0.5 | <0.25–0.5 | <0.25 | — | <0.25 | Malik et al., 201231 | |

| H37Rv | A74S + D94G | 16–32 | 16 | 16 | — | 4–16 | ||

| A90V | 2–4 | 2–4 | 0.5–2 | — | 0.5–1 | |||

| Erdman | A74S | 1–2 | 1 | 1 | — | 0.5–1 | ||

| A90V | 2–8 | 4 | 0.5–4 | — | 0.5–1 | |||

| CDC1551 | D94G | 8 | 8 | 8 | — | 2 | ||

| gyrB | — | N510D | 120 | — | 500 | 45 | 35 | Aubry et al., 200629 |

| — | WT | — | 7 | 22 | 9 | 16 | Kim et al., 201136 | |

| E540V | — | 251 | 82 | 37 | 61 | |||

| — | WT | 10 | — | 8 | 3 | 2.5 | Pantel et al., 201237 | |

| D500A | 22 | — | 25 | 8 | 6 | |||

| N538T | 28 | — | 24 | 14 | 12 | |||

| T539P | 30 | — | 17 | 13 | 12 | |||

| E540V | 80 | — | 64 | >20 | >20 | |||

| H37Rv or Erdman | WT | 0.5 | <0.25—0.5 | <0.25 | — | <0.25—0.5 | Malik et al., 201231 | |

| N538D | 4 | 4 | 2 | — | 1 | |||

| T539P | 0.5–1 | 1 | 0.5–1 | — | 0.5–1 | |||

| N538K | 2 | 2 | 1 | — | 1–2 | |||

| H37Rv | E540V | 4 | 2 | 1–2 | — | 0.5–1 | ||

| D500H | 4–8 | 1–2 | 2–4 | — | <0.25–0.5 | |||

| D500N | 4 | 1 | 2 | — | <0.25–0.5 | |||

| N538D + T546M | 2 | 4 | 2 | — | 1 | |||

| N538T + T546M | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | — | 0.5–1 | |||

| A543V | 2 | 1 | 1 | — | 0.5–1 | |||

| E540D | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | — | 2–4 | |||

| R485C + T539N | 4–8 | 2 | 2–4 | — | 2 | |||

| Erdman | E540V | 4 | 2–4 | 2 | — | 1 | ||

| D500H | 4–8 | 1 | 2–4 | — | 0.5 | |||

| D500N | 4 | 2 | 2 | — | 0.5 | |||

| N538D + T546M | 4 | 8 | 2 | — | <0.25–1 | |||

| N538T + T546M | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | — | <0.25–1 | |||

| T539N | 2 | 2 | 1 | — | 1 | |||

| E540D | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | — | 2 | |||

| R485C + T539N | 8 | 4 | 4 | — | 4 |

aIC50s were determined directly on recombinant gyrA and gyrB subunits produced in E. coli plasmids. All references except for Malik et al.,31 used IC50s.

bCritical concentration: MIC > 2 mg/L.

cCritical concentration: MIC > 2 mg/L.

dCritical concentration: MIC > 1 mg/L.

eMIC > 0.5 mg/L (low-level resistance) and >2 mg/L (high-level resistance).

Mutations that increased susceptibility or had no effect on FQ resistance

Aubry et al.29 reported that gyrA mutations T80A and T80A + A90G led to a reduced IC50; A90G alone did not affect the FQ IC50 (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Malik et al.31 also found that the gyrA double mutation T80A + A90G had no significant effect on MICs and actually decreased the MIC for ofloxacin. Transformants with G247S and A384V, located outside the gyrA quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR), had similar FQ MICs compared with negative controls.

Matrat et al.33 looked to identify the minimum number of mutations needed to increase FQ susceptibility in Mtb to levels similar to those in Escherichia coli. An A83S mutation in gyrA was sufficient to decrease moxifloxacin IC50 to a susceptible range for E. coli. To decrease the ofloxacin IC50 to a susceptible range similar to E. coli, the A83S mutation had to be coupled with a second substitution, either M74I in gyrA or R447K in gyrB. Modification of the vicinity of A83 (residues 84 and 85) did not have any effect on FQ susceptibility.

Kim et al.32 explored whether lineage-specific amino acid residues affect FQ resistance. They conducted in vitro IC50 studies using recombinant DNA gyrase bearing an S95 residue in gyrA. The wild-type (gyrA containing S95) and gyrA containing A74S with the S95 demonstrated similar levels of in vitro FQ susceptibility. The authors believed the reason that this mutation did not show the higher FQ resistance described in previous reports was because those earlier strains from China were Beijing, which contains threonine at position 95, which may already enhance resistance by altering interactions between α4 and α3 helices.34,35

gyrB

Mutations that caused FQ resistance

Aubry et al.29 found that the N510D mutation in gyrB led to an IC50 elevation (Table 4). Kim et al.36 found that a gyrase bearing the E540V amino acid substitution in gyrB, mimicking a clinical strain from Bangladesh, was highly resistant to inhibition by four FQs. Pantel et al.37 reported that D500A and N538T (located in the QRDR) and T539P (located outside the QRDR) conferred low-level resistance, in contrast to E540V (also outside the QRDR), which conferred higher-level resistance. In contrast to the findings of Kim et al.36 and Pantel et al.,37 Malik et al.31 found that the resistance pattern of the E540V mutation was dependent on the genetic background of the mutated strain. In H37Rv, E540V conferred consistent susceptibility to ciprofloxacin but conferred resistance to levofloxacin and ofloxacin and low-level resistance to moxifloxacin. In the Erdman background, E540V exhibited cross-resistance to all four FQs tested during one round of testing but was susceptible to moxifloxacin on repeat testing. In addition, Malik et al.31 found that transformants harbouring D500A had increased MICs for levofloxacin and ofloxacin (at least 4-fold), which were still considered in the susceptible range; the MICs for ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin were unaffected.

Malik et al.31 report that transformants harbouring gyrB D500H or D500N were resistant to levofloxacin and ofloxacin but susceptible to ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin. The N538D-containing transformant exhibited resistance to all four FQs. The N538D + T546M double mutation conferred resistance to all of the FQs tested when introduced into Erdman but did not significantly increase the MIC to a greater extent than N538D alone. The N538D + T546M double mutation resulted in slightly different results in the H37Rv genetic background, where it was resistant to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin but susceptible to ofloxacin. Transformants carrying another variant at codon 538, N538T, plus T546M were susceptible to all FQs tested. These data suggest that T546M does not play a synergistic role in FQ resistance and N538T does not confer resistance. The R485C and T539N gyrB mutations each independently increased the MIC, but not to clinical resistance levels. The T539N mutation did confer low-level resistance to moxifloxacin in the Erdman strain. When introduced together into H37Rv, gyrB R485C + T539N conferred resistance to ofloxacin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin; the same double mutation in Erdman conferred resistance to all four FQs tested. Based on these results, R485C and T539N individually increase the FQ MIC slightly but in combination they act synergistically to increase the MIC above the critical concentration to confer clinical resistance.

Malik et al.31 found that the T539P mutation alone increased the levofloxacin MIC, but not above the critical concentration; this mutation did not substantially affect the MIC for any other FQ. Both A543T and A543V increased (2-fold to 4-fold) the MICs for levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin but had no effect on the moxifloxacin MIC. These were still below the accepted critical concentration for clinical resistance. The N538K mutation exhibited low-level resistance to moxifloxacin and increased the MICs (4-fold) of ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin and levofloxacin, although these increases were not sufficient to be considered resistant.

Mutations that increased susceptibility or had no effect on FQ resistance

Pantel et al.38 studied eight substitutions in gyrB (D473N, P478A, R485H, S486F, A506G, A547V, G551R and G559A) and found that none of them was implicated in FQ resistance (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Malik et al.31 found that gyrB M330I, V340L and T546M did not confer resistance to any FQ tested. Transformants with D533A were also susceptible to all four FQs. T546M did not confer FQ resistance. Matrat et al.33 found that the R447K substitution conferred increased susceptibility.

Discussion

In this systematic review we identified papers that introduced drug resistance-conferring mutations into eight genes (katG, inhA, kasA, embB, embC, rpoB, gyrA and gyrB) and one intergenic region (furA-katG). Within these genomic regions, 25 individual mutations plus 3 double mutations caused clinical resistance to first-line drugs, and 8 resulted in no change in inhibitory concentration. A further 18 individual mutations and 7 double mutations caused clinical resistance to one or more FQs, with 26 individual mutations and 4 double mutations conferring no change in FQ inhibitory concentrations (Tables 2–4 and Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Several studies found that mutations can have a different effect on the drug MIC, depending on the background strain into which it is introduced. For example, the rpoB mutation Q513L led to high-level resistance to rifampicin in strain KL463, lower-level resistance in strain KL1936 and no significant increase in MIC in H37Ra. In embB, mutation M306I (ATC) caused a moderately higher MIC in strain 5310 compared with strain 210 and H37Rv. Similarly, embB mutation M306I (ATA) resulted in varied levels of MIC: 7 mg/L in strain 210; 16 mg/L in strain 5310; 10 mg/L in a Beijing F2 strain; and both 4 mg/L and 10 mg/L in two H37Rv-derived strains in two different studies. Depending on what value is chosen as the critical concentration cut-off, the latter H37Rv could be considered ‘susceptible’ and the former ‘resistant’.9

Although all MICs consistently increased, such discrepancies underline the limitations of the currently accepted critical concentration cut-offs in determining clinical ‘resistance’, and suggest that epistasis between the introduced mutations and other genetic variation elsewhere in the genome plays an important role in influencing the resistance phenotype. Mutation–mutation interactions have been previously noted to influence the drug resistance phenotype of other pathogens such as HIV.39 The observation of epistasis influencing the drug resistance phenotype in Mtb challenges the reductionist view that one ‘correct’ mutation is sufficient to result in resistance to a particular drug, and supports the more comprehensive study of additional genes in the Mtb genome that can modulate or contribute to the resistance phenotype in an alternative ‘multi-hit’ model.

This systematic review also demonstrates that the same drug resistance mutations can cause varying levels of resistance to different members of the same drug class, For example, the D500H mutation in gyrB led to resistance to earlier-generation FQs (ofloxacin, levofloxacin) but not moxifloxacin. Likewise, clones containing the D516V mutation in rpoB showed resistance to rifampicin and rifapentine but maintained susceptibility to rifabutin. This finding is consistent with similar observations made in clinical strains that exhibited rifampicin resistance with rifabutin susceptibility by current cut-offs.40

It is possible that these observations may be overemphasized by the current, arguably arbitrary, drug concentration cut-offs for clinical resistance. However, the observation that in isogenic backgrounds the same mutation leads to smaller increments in MIC for some members of the same drug class, coupled with the known higher pharmacological potency of some of these agents seems likely to have treatment implications. To date, there are no direct clinical or pharmacological data to support the clinical efficacy of treating Mtb resistant to one member of the FQ or rifamycin drug class with another member, but observations of improved treatment outcomes for patients with extensively drug-resistant TB (by definition resistant to a member of the FQ drug class) who were treated with later-generation FQs (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) provide some indirect support for this notion.41–44 Evidence from this review thus emphasizes the importance of further studying FQs and alternative rifamycins to assess their clinical value in the treatment of Mtb resistant to other members of the same drug class.

This systematic review highlights some notable lack of allelic exchange data for several of the genes known to be associated with drug resistance. Notably, we found no studies that met our inclusion criteria which studied pncA, rrs, inhA promoter region, or ethA encoding resistance to the drugs pyrazinamide, streptomycin, the aminoglycosides (amikacin, capreomycin, kanamycin) and ethionamide. Even within the genes studied, only a subset of the common mutations was studied in most cases. For example, we found no report of allelic exchange experiments performed at codon 91 of gyrA, or codons 446, 447, 461, 494, 501 and 504 of gyrB, codons that have previously been associated with FQ resistance in clinical strains.45,46

Rapid molecular assays for detecting drug resistance are currently limited, with GeneXpert (Cepheid) only testing for rifampicin resistance, the sensitivity of the GenoType MTBDR test (Hain Lifescience) for the detection of isoniazid resistance reported to be in the 80%–90% range47–49 and the GenoType MTBDRsl assay showing a low level of performance for FQs, aminoglycosides and ethambutol (reported sensitivities of 87%–89%, 21%–100% and 39%–57%, respectively).50–53 Their accuracy is largely dependent on the strength of the association between a specific mutation and the resistance phenotype. These and further allelic exchange studies may point towards recommendations for improving the diagnostic accuracy of molecular-based resistance assays, depending on their correlation with the frequency of these mutations found in clinical strains. For example, including embB mutations in codon 406, shown to increase the ethambutol MIC to a clinically significant level in this review and also observed in clinical isolates in India, Russia and the USA,54–56 could improve the sensitivity for detecting resistance to ethambutol in those particular geographic settings. An updatable database on mutations associated with resistance worldwide, such as TBDReaMDB, may serve as a cross-check for the clinical relevance of including newly identified mutations from allelic exchange studies into diagnostic tests.46 Finally, the reviewed allelic exchange experiments suggest that mutation Q513L in rpoB, currently assayed in the GeneXpert pipeline, does not result in a consistent increase in rifampicin MIC, depending on the strain background genome. This may have an impact on GeneXpert's specificity.

It is critical to note that drug susceptibility testing, although the gold standard, is not 100% accurate. A lack of concordance with resistance screening may therefore not necessarily imply that resistance has been missed. It has been shown that in vitro data do not necessarily correlate with in vivo data and vice versa. For example, mutations leading to only slightly raised in vitro rifampicin resistance may indeed have clinical significance,57 while mutations with dramatic in vitro effects may be unfit in vivo and hence very rare in patient isolates.12 Whole genome sequencing and convergence analysis may be particularly useful in identifying potential mutations of interest requiring confirmation.58,59

This systematic review highlights the current understanding of the causal relationships of different mutations on phenotypic resistance in Mtb as studied via allelic exchange. Given increasing reports of Mtb strains with higher levels of drug resistance worldwide, this review provides new suggestions for drug resistance diagnostics development and highlights some gaps in our knowledge of genotype–phenotype relationships that are worth further study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) (SFRH/BD/33902/2009 to H. N.-G.), the National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Center (1K01 TW009213 to K. R. J.), departmental funds of the pulmonary division of Massachusetts General Hospital to M. R. F. and the National Institutes of Health/NIAID (U19 A1076217 to M. B. M.).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Table S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).

References

- 1.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2012. Geneva: WHO; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf. (2 May 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, et al. Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans CA. GeneXpert—a game-changer for tuberculosis control? PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SY, Kim H, Kim SY, et al. The Xpert® MTB/RIF assay evaluation in South Korea, a country with an intermediate tuberculosis burden. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1471–6. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson KR, Theron D, Kendall EA, et al. Implementation of GenoType MTBDRplus reduces time to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis therapy initiation in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;56:503–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqi N, Shamim M, Hussain S, et al. Molecular characterization of multi-drug resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients in North India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:443–50. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.443-450.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang K, Sun H, Zhao Y, et al. Characterization of rifampin-resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Sichuan in China. Tuberculosis. 2013;93:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tessema B, Beer J, Emmrich F, et al. Analysis of gene mutations associated with isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol resistance among Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;10:12–37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottger EC. The ins and outs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1128–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boshoff HI, Mizrahi V. Purification, gene cloning, targeted knockout, overexpression, and biochemical characterization of the major pyrazinamidase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5809–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5809-5814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heym B, Stavropoulos E, Honore N, et al. Effects of overexpression of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase AhpC on the virulence and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1395–401. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1395-1401.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergval IL, Schuitema AR, Klatser PR, et al. Resistant mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis selected in vitro do not reflect the in vivo mechanism of isoniazid resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:515–23. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aubry A, Pan X, Fisher LM, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA gyrase: interaction with quinolones and correlation with antimycobacterial drug activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1281–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1281-1288.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pym AS, Saint-Joanis B, Cole ST. Effect of katG mutations on the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the implication for transmission in humans. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4955–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4955-4960.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pym AS, Domenech P, Honoré N, et al. Regulation of catalase–peroxidase (KatG) expression, isoniazid sensitivity and virulence by furA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:879–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vilcheze C, Wang F, Arai M, et al. Transfer of a point mutation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhA resolves the target of isoniazid. Nat Med. 2006;12:1027–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardon E, Lin S, Pinsky B, et al. First documentation of isoniazid reversion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1347–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando H, Kitao T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T. Downregulation of katG expression is associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1615–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safi H, Sayers B, Hazbon MH, et al. Transfer of embB codon 306 mutations into clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains alters susceptibility to ethambutol, isoniazid, and rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2027–34. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01486-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starks AM, Gumusboga A, Plikaytis BB, et al. Mutations at embB codon 306 are an important molecular indicator of ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1061–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01357-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plinke C, Walter K, Alv S, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis embB codon 306 mutations confer moderately increased resistance to ethambutol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2891–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00007-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goude R, Amin A, Chatterjee D, et al. The arabinosyltransferase EmbC is inhibited by ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4138–46. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00162-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safi H, Fleischmann RD, Peterson SN, et al. Allelic exchange and mutant selection demonstrate that common clinical embCAB gene mutations only modestly increase resistance to ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:103–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01288-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams DL, Spring L, Collins L, et al. Contribution of rpoB mutations to development of rifamycin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1853–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill SK, Garcia GA. Rifamycin inhibition of WT and Rif-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in vitro. Tuberculosis. 2011;91:361–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaczek A, Brzostek A, Augustynowicz-Kopec E, et al. Genetic evaluation of relationship between mutations in rpoB and resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to rifampin. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siu GKH, Zhang Y, Lau TCK, et al. Mutations outside the rifampicin resistance-determining region associated with rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:730–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onodera Y, Tanaka M, Sato K. Inhibitory activity of quinolones against DNA gyrase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:447–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aubry A, Veziris N, Cambau E, et al. Novel gyrase mutations in quinolone-resistant and -hypersusceptible clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: functional analysis of mutant enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:104–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.104-112.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matrat S, Veziris N, Mayer C, et al. Functional analysis of DNA gyrase mutant enzymes carrying mutations at position 88 in the A subunit found in clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4170–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00944-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik S, Willby M, Sikes D, et al. New insights into fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: functional genetic analysis of gyrA and gyrB mutations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H, Nakajima C, Kim YU, et al. Influence of lineage-specific amino acid dimorphisms in GyrA on Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to fluoroquinolones. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matrat S, Aubry A, Mayer C, et al. Mutagenesis in the α3α4 GyrA helix and in the toprim domain of GyrB refines the contribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA gyrase to intrinsic resistance to quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2909–14. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01380-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Z, Zhang J, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of gyrA gene mutations between laboratory-selected ofloxacin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi R, Zhang J, Li C, et al. Emergence of ofloxacin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from China as determined by gyrA mutation analysis using denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography and DNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4566–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01916-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Nakajima C, Yokoyama K, et al. Impact of the E540V amino acid substitution in GyrB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on quinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3661–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00042-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pantel A, Petrella S, Veziris N, et al. Extending the definition of the GyrB quinolone resistance-determining region in Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA gyrase for assessing fluoroquinolone resistance in M. tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1990–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06272-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pantel A, Petrella S, Matrat S, et al. DNA gyrase inhibition assays are necessary to demonstrate fluoroquinolone resistance secondary to gyrB mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4524–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00707-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsch MS, Günthard HF, Schapiro JM, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection: 2008 recommendations of an International AIDS Society-USA panel. Top HIV Med. 2008;16:266–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schön T, Juréen P, Chryssanthou E, et al. Rifampicin-resistant and rifabutin-susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains: a breakpoint artefact? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2074–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobson KR, Tierney DB, Jeon CY, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:6–14. doi: 10.1086/653115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rustomjee R, Lienhardt C, Kanyok T, et al. A phase II study of the sterilizing activities of ofloxacin, gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:128–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang JY, Wang JT, Tsai TH, et al. Adding moxifloxacin is associated with a shorter time to culture conversion in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takiff H, Guerrero E. Current prospects for the fluoroquinolones as first-line tuberculosis therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5421–29. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00695-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maruri F, Sterling TR, Kaiga AW. A systematic review of gyrase mutations associated with fluoroquinolone-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a proposed gyrase numbering system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:819–31. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandgren A, Strong M, Muthukrishnan P, et al. Tuberculosis drug resistance mutation database. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavusoglu C, Turhan A, Akinci P, et al. Evaluation of the Genotype MTBDR assay for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2338–42. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Somoskovi A, Dormandy J, Mitsani D, et al. Use of smear-positive samples to assess the PCR-based genotype MTBDR assay for rapid, direct detection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex as well as its resistance to isoniazid and rifampin. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4459–63. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01506-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aslan G, Tezcan S, Emekdas G. Evaluation of the genotype MTBDR assay for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance in clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex clinical isolates. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2009;43:217–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hillemann D, Rusch-Gerdes S, Richter E. Feasibility of the GenoType MTBDRsl assay for fluoroquinolone, amikacin, capreomycin, and ethambutol resistance testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1767–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang WL, Chi TL, Wu MH, et al. Performance assessment of the GenoType MTBDRsl test and DNA sequencing for detection of second-line and ethambutol drug resistance among patients infected with multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2502–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00197-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brossier F, Veziris N, Aubry A, et al. Detection of GenoType MTBDRsl test of complex mechanisms of resistance to second-line drugs and ethambutol in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1683–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01947-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Said HM, Kock MM, Ismail NA, et al. Evaluation of the GenoType MTBDRsl assay for susceptibility testing of second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:104–9. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srivastava S, Garg A, Ayyagari A, et al. Nucleotide polymorphism associated with ethambutol resistance in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53:401–5. doi: 10.1007/s00284-006-0135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramaswamy SV, Amin AG, Goksel S, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms associated with ethambutol resistance in human isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:326–36. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.326-336.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Srivastava S, Ayyagari A, Dhole TN, et al. embB nucleotide polymorphisms and the role of embB306 mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to ethambutol. Int J Med Microbiol. 2009;299:269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Deun A, Barrera L, Bastian I, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with highly discordant rifampin susceptibility test results. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3501–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01209-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hazbon MH, Motiwala AS, Cavatore M, et al. Convergent evolutionary analysis identifies significant mutations in drug resistance targets of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3369–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00309-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farhat MR, Shapiro BJ, Kieser KJ, et al. Convergent evolution reveals targets of positive selection in drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Nat Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ng.2747. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.