Abstract

Neglect is a pervasive form of child maltreatment. Health care practitioners often struggle with deciding when an action (or lack of action) by a caregiver constitutes inadequate care and is neglectful. The present article discusses the epidemiology, risk factors and outcomes of neglect. In addition, assessment using objective markers, such as harm and potential harm, in the identification of neglect is described, and unique factors that impact assessing and addressing issues of neglect in the clinical setting are discussed. Practical strategies for intervening in cases of neglect are discussed, including how to engage families in which there are concerns for neglect, mandated reporting, working collaboratively with children’s services, ongoing monitoring of families, and how health care professionals can effectively engage in neglect prevention and advocacy.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Child neglect, Protective services

Abstract

La négligence est une forme envahissante de maltraitance d’enfants. Les dispensateurs de soins éprouvent souvent de la difficulté à déterminer si un geste (ou l’absence d’un geste) posé par une personne qui s’occupe de l’enfant est inadéquat et constitue une manifestation de négligence. Le présent article traite de l’épidémiologie, des facteurs de risque et des issues de la négligence. De plus, les auteurs y décrivent un mode d’évaluation au moyen de marqueurs objectifs, tels que les préjudices réels ou potentiels, pour dépister la négligence, et y abordent des facteurs uniques qui ont une incidence sur l’évaluation et la résolution de la négligence en milieu clinique. Ils proposent des stratégies pratiques pour intervenir en cas de négligence, y compris comment aborder les familles chez qui on craint de la négligence, les signalements obligatoires, la collaboration avec les services de protection de la jeunesse, la surveillance continue des familles et la manière dont les professionnels de la santé peuvent participer de manière efficace à la prévention de la négligence et prendre position à cet égard.

DEFINITION

Neglect is a pervasive form of child maltreatment. A variety of definitions for neglect have been proposed, with many focusing on omissions in care giving. However, at its core, neglect occurs when a child’s basic needs for food, shelter, clothing, education, nurturing and supervision are not being adequately met, potentially or directly impeding normal development and safety (1,2). In practice, this definition is challenging to apply. It is often difficult to decide when an action (or lack of action) by a caregiver constitutes inadequate care and is neglectful (3,4). In the present review, we discuss the prevalence, risk factors, challenges in diagnosis and management recommendations to address the challenging and important issue of neglect.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Neglect and emotional abuse are the most common forms of maltreatment of children. According to the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (5), one-third of substantiated investigations for child maltreatment in 2008 involved neglect, representing >28,000 cases. Substantiated cases of neglect were often chronic in nature, with more than two-thirds of these cases involving multiple incidents. It is essential that health care practitioners who work with children and families have an approach to this challenging issue with significant implications for health and well-being.

RISK FACTORS

Parental problems are commonly considered to be the main contributor to neglect. Certainly, parental factors, such as mental health issues, intellectual deficits and substance abuse, have been associated with neglect (6,7). Developmental-ecological theory, however, suggests that child, parental, parent-child, family, community and society factors may all contribute to neglect. Often, several factors interact and play a role in the occurrence of neglect (eg, a single parent experiencing depression and substance abuse in a community with few resources) (8).

Younger children, children with complex medical problems, and children with developmental disabilities are at an increased risk for neglect (9,10) due to the heightened challenge of meeting the basic needs of these populations. However, while less often recognized, older children and adolescents with emotional and behavioural problems are also at risk. Consider, for example, the adolescent with type 1 diabetes presenting with recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis whose unmet mental health issues are a contributor to poor adherence to the insulin treatment regimen.

Family factors and characteristics of the parent-child relationship associated with neglect include less positive engagement between the parent and child, inappropriate parental expectations, chaotic family environments, increased family stress (8) and intimate partner violence (11–13).

The community and society in which the child lives may also contribute to the occurrence of neglect. Communities without community centres and other supportive resources and communities in which caregivers are socially isolated often have a higher prevalence of neglect (8). Although it is important to note that many impoverished families provide safe and nurturing environments for their children, poverty has consistently been found to contribute to neglect (14,15). A negative or dismissive view of children in society may result in fewer resources focused on children’s needs and thus foster neglect (8). Hence, a developed and prosperous society may be neglectful of children by not making available resources that meet the needs of its children.

OUTCOMES

Neglected children are at risk for physical, emotional and behavioural disorders in childhood (8,16) and adulthood (17). Adverse psychological sequelae may develop via several pathways. Childhood adversity jeopardizes neurodevelopmental progress (18). Adversity at specific vulnerable times, such as during infancy, predicts later adverse psychological outcomes such as disorders of attachment, anxiety and depression (19). This developmental sensitivity is apparent in studies of institutionalized Romanian children and other populations who have experienced significant childhood adversity resulting in neuroendocrine changes (20). In some situations, it may not be the neglect per se, but rather highly comorbid conditions, such as physical or sexual abuse, as well as the contextual circumstances (eg, substance abuse) that lead to poor psychological outcomes. For example, neglect with comorbid abuse is associated with an increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (21). These associated risks warrant attention to ensure children’s safety, health and development. Careful surveillance of emotional and behavioural functioning is important in children who have experienced or are at risk for neglect, and a low threshold for intervening or making a mental health referral is warranted.

In addition to developmental and psychological outcomes, children previously investigated for neglect are at risk for future neglect regardless of previous child welfare intervention or disposition (22). This may involve the same or a different type of neglect. For example, a child with a history of medical neglect may continue to inadequately adhere to medical treatment, or may experience a different problem such as poor school attendance (educational neglect).

TYPES OF NEGLECT AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

There are several forms of neglect, and the specific type of neglect influences how the concerns manifest. The different forms are listed in Table 1. What unifies the various forms of neglect is the interference with normal childhood development, health and safety resulting from a child’s basic need(s) not being adequately met. The following sections consider neglect in various typical presentations to the health care practitioner, including neglect as a primary concern and requests for assessment of neglect concerns by child protection workers.

TABLE 1.

Types of neglect

| Type of neglect | Definition |

|---|---|

| Physical | Inadequate food, clothing, shelter, hygiene |

| Medical | Failure to provide prescribed medical care or treatment or failure to seek appropriate medical care in a timely manner |

| Dental | Failure to provide adequate dental care or treatment |

| Supervisional | Failure to provide age-appropriate supervision |

| Emotional | Failure to provide adequate nurturance or affection, failing to provide necessary psychological support, or allowing children to use drugs and/or alcohol |

| Educational | Failure to enroll a child in school or failure to provide adequate home schooling, failure to comply with recommended special education, allowing chronic truancy |

| Other | Includes exposing children to domestic violence, or engaging or encouraging children to participate in illegal activities such as shoplifting or drug dealing |

Adapted from reference 31

Neglect as the primary concern

Health professionals encounter many situations in which concerns of neglect are front and centre, such as when a child does not receive necessary health care or a mother’s depression compromises her ability to provide adequate care for her infant. Other common presentations include failure to thrive (23,24), nonadherence to medical treatment, and failure or delay in seeking care for worrisome symptoms (25). It is important that practitioners probe the underlying circumstances in cases of injury and ingestion, maximizing recognition of neglect and providing an opportunity to intervene to prevent further adverse outcomes. For example, a four-year-old girl presents with a limp after jumping off a tree in the backyard. She has no injuries other than right distal tibial point tenderness and radiographic findings of a buckle fracture. The history accounts for the injury and no concerns of child abuse arise. This could be (and often is) the end of the evaluation unless the health professional probes the circumstances surrounding the fall and discovers concerns related to inadequate supervision and neglect (26).

In each case, there is a need to consider child, family, community and societal risk factors that may be contributing to neglect.

Referrals from child welfare

Children may be referred to child health professionals by child welfare social workers to assess for reported neglect. In these circumstances, families may feel forced to have their child(ren) undergo a medical evaluation. Defining the role of the health professional in the evaluation of neglect, what is being requested, and potential conflicts (patient confidentiality, forensic versus clinical relationship) should be clarified with both the child welfare worker and the family before evaluation. It is important to work with the family and the child protection agency when possible, to obtain consent for information to be shared with one another.

The family’s perception and concerns should be solicited and addressed and, if developmentally feasible and appropriate to the child protection/legal context and involvement, there is great value in talking directly with the child regarding the concern for neglect. In addition, it is important to clarify the circumstances regarding the possible neglect by talking with the child-welfare caseworker, sharing concerns and strengths of the family after the evaluation.

ASSESSMENT

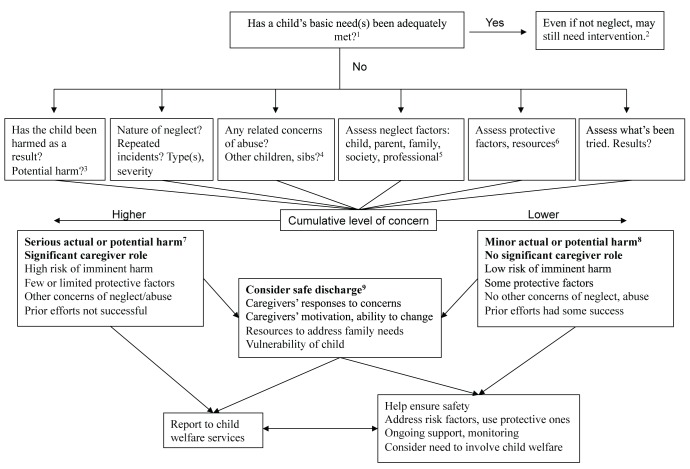

A stepwise approach to the assessment of neglect concerns may help to guide the practitioner in determining the most appropriate management plan (Figure 1). Identifying harm is one useful objective marker in the assessment of possible neglect (23). If a child is harmed due to a circumstance that can reasonably be attributed to inadequate care or supervision, one can construe that as neglect. For example, it is possible that asthma in a particular child is difficult to control, thus the reason for a subsequent exacerbation and hospitalization. However, it is not uncommon for a family to be nonadherent to the asthma regimen, or for a child to live in an apartment where cockroaches trigger the asthma and the landlord does not address the infestation, leading to concerns of neglect, with harm resulting from discomfort and illness, missed school, and isolation from friends and family during hospital admission. It is an important first step to understand the relative contributions of the medical etiology and the adequacy of care. When concerns of inadequate care arise, contributors to the problem may vary and are important to assess to identify how best to ensure the child’s needs are met and future harm is prevented.

Figure 1).

Guidelines for approaching possible child neglect in child health care settings. 1) Health care (medical, mental and dental, food, hygiene/sanitation, safety/supervision) and development (emotional, cognitive). There is no simple way to rate ‘adequacy,’ but ‘inadequacy’ should be based on evidence that the circumstances pose risks to a child’s health, development and safety, and may cause actual or potential harm. 2) Children’s needs are naturally met on a continuum from ‘fully’ to ‘not at all.’ Even when circumstances do not cross the ‘neglect threshold’ for a child welfare report, intervention may still be helpful. 3) Potential harm is of concern, especially with a view to prevention. Estimate the severity of the potential harm and the likelihood of it occurring. 4) Neglect often involves siblings (sibs) or other children in the home. It is helpful to try to assess them as well. 5) A good understanding of what is underpinning the neglect is key to intervening appropriately. There are often multiple contributors: child (eg, disabled, refusing to take medications), parent (eg, depressed, substance abuse), family (eg, intimate partner violence, father not involved), community (eg, many stressors, few supports), societal (eg, poverty, lack of health insurance), and professional (eg, not responding to ‘red flags’, missed diagnoses). 6) In addition to risk factors, there are usually protective factors that may buffer the stressors. It is important to identify these because they are often helpful in working effectively with families. ‘Internal’ protective factors include a child’s wish to feel well and a parent’s caring toward the child. ‘External’ protective factors include supportive extended family, community resources/agencies and you – as an involved professional. 7) This illustrates a severe situation. The first two items in bold clearly require child welfare involvement. The other factors may or may not be present. In addition to a child welfare report, consider what other interventions may benefit the family. 8) This illustrates a less severe situation. Other interventions may first be attempted, while considering the need for a child welfare report. Many situations may fall in the grey zone between ‘severe’ and ‘less severe’ and require clinical judgment as how to intervene. This figure is intended as a general guide. 9) When discharging a child from an in- or outpatient setting, it is important to consider whether it is safe for the child to go home. In addition to information from the adjacent boxes, it is useful to assess the parents’ responses to the concerns, their motivation and ability to better protect their child, and the availability of needed resources (eg, drug treatment). Special consideration should be given to the child’s vulnerability, including age/development, medical or behavioural problems, and ability to cope (eg, take her own medications)

Another aspect to consider in the diagnosis of neglect is potential harm. There are a few elements to consider regarding potential harm, including the likelihood of harm occurring and the severity of the potential harm. Consider two infections – tinea corporis and bacterial meningitis. With a minor infection localized to the skin such as tinea, discomfort and scratching could lead to further complications (potential for harm). However, even without treatment, the tinea may resolve without sequelae. In contrast, a clearly sick child with meningitis who does not receive medical care could experience devastating consequences. Lack of care for a minor condition that does not result in significant harm to a child is usually acceptable, whereas inadequate care for a condition with highly predictable and potentially severe outcomes constitutes neglect. These two infections are at the extremes of the spectrum; more often, health professionals face circumstances that fall somewhere in the middle.

When assessing the weight to place on a potentially serious complication in the assessment of neglect concerns, it is also useful to consider the immediacy of potential harm as well as later opportunities to effectively intervene. Bacterial meningitis can directly impact brain tissue. In contrast, with a common infection such as otitis media, there is a small but real likelihood of serious complications if untreated; however, otitis usually progresses slowly, allowing later opportunities to intervene and prevent the harm.

When assessing concerns of neglect, it is helpful to focus on whether the needs of the child were met in the caregiving environment, and the resultant harm – actual or potential – rather than focusing on the intentions of parents or caregivers. The concerned health practitioner should not assume the intention of a caregiver in cases of neglect, but rather explore the circumstances that contributed to the occurrence of neglect. Most parents do not intend to harm; rather, obstacles impede the ability to meet their child’s needs. Intentionality is inherently difficult to assess and attempting to assess intentionality may aggravate a negative stance toward the parents. However, in determining an appropriate intervention for neglect, understanding caregiver thinking underpinning their action or inaction guides the management plan.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR ADDRESSING NEGLECT

It is useful to approach neglect as a symptom, rather than a disease or disorder. The challenge is to probe what is underpinning the neglect. It is recommended that practitioners ask open-ended questions (eg, “tell me what happened”) that enable the family to describe the circumstances surrounding the possible neglect. Interviewing family members separately is optimal. Collateral information from other family members, and health and other professionals, is often useful. In addition, consideration of how the health care professional and system may be contributing to the neglect, such as when access to care decreases due to changes in clinic hours or availability of supportive resources, is recommended. Some specific recommendations follow:

Maintain alliance with family

When confronted with concerns of neglect, it is important for health professionals to assess the safety, health and development of the patient while maintaining an alliance with the family to more effectively promote change. In this context, the health care professional and the family work together openly to clarify the etiology of the neglect. Because many cases of potential neglect may not warrant the involvement of the child welfare system, an optimal approach to improve the child’s care requires understanding the contributing factors to the occurrence of neglect and developing a plan tailored to the individual needs of the child and family. It is essential that health professionals avoid the common pitfall of blaming the parent, but rather work with the family to uncover the contributing factors to neglect and engage and motivate and support the family toward more appropriate care.

Bring neglect out from the shadows

In most cases, the health professional should be forthright with the family regarding concerns, and the assessment and management plan. Families may benefit from engaging other family members, community and religious supports and services to tackle problems contributing to the neglect. Forthrightly but kindly addressing neglect can help transform the problem from a hidden embarrassment (eg, about not having enough food) to an open, solvable problem.

Consider duration of treatment

The health professional, working with the family, should develop appropriate timelines for change – with clear and measurable outcomes. A written contract that the family and health care provider both sign establishes a concrete record of the agreed-on plan and lays the foundation to assess future progress (25). Often, neglect is the product of multiple factors and a chronically dysfunctional situation, and improvement may require a prolonged effort. Informal and formal supports and services may both be needed, and regular follow-up with the same health professional is optimal to assess progress and modify the management plan when necessary.

Focus on achieving rather than avoiding

A positive, constructive approach helps motivate parents to engage in interventions. Treatment objectives should focus on increasing positive behaviours (eg, attending school) rather than decreasing negative behaviours (eg, fewer school absences). Components of motivational interviewing (27), such as demonstrating a discordance between current behaviours and future goals, are useful in moving individuals toward change.

Mandated reporting

When addressing neglect, health professionals are advised to always consider their mandated duty to report suspected maltreatment to child welfare services, especially in situations in which moderate or severe harm is involved, when initial interventions have failed and when other forms of maltreatment are suspected. In addition, due to the lack of social work availability in most clinical settings, child welfare system help is often needed to assess the home environment when all of the risks to the child are not clear and there is reason for concern.

Ongoing monitoring

It is important that adequacy of care and factors in the environment contributing to disease or injury be considered in children and families presenting for health care. In families with a history of neglect, the use of case management, patient management contracts, and the provision of additional resources may be indicated for monitoring medical, developmental, psychological, educational or safety concerns.

The individual, family, community and social conditions that contributed to the occurrence of neglect may persist and may wax and wane. It is important, therefore, to routinely follow-up with the family to monitor the situation and help when needed. For example, follow-up with a mother whose postpartum depression contributed to medical neglect may enable the practitioner to advocate for her and facilitate a referral. When the practitioner has developed an alliance with the family, this periodic inquiry will likely be viewed positively as caring and helpful.

When child welfare services are involved, it is helpful to ask parents for consent for sharing of information back and forth with the agency. Open communication is helpful in cases of neglect throughout the follow-up period.

Strategies for prevention

There are a few interventions to prevent child maltreatment with promising findings. Two specific home visitation programs, the Nurse-Family Partnership and Early Start, have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing maltreatment in randomized controlled trials (28). Clinic-based models are now available to screen for and help address family psychosocial risk factors that contribute to neglect. One such program, the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model, has been demonstrated to be practical and effective in paediatric primary care settings (29,30). This model enhances physician awareness of psychosocial contributors to neglect, provides a tool to efficiently screen for targeted problems, and offers a multidisciplinary model to effectively address problems facing many families.

SUMMARY

Health professionals aware of the pervasive nature of and significant short- and long-term sequelae associated with neglect are well positioned to be advocates for children. Advocacy within one’s community and nationally by improving education regarding neglect among health professionals, policy makers and families is needed to help prevent neglect and minimize its significant adverse short- and long-term impacts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helfer RE. The neglect of our children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37:923–42. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubowitz H, Bennett S. Physical abuse and neglect of children. Lancet. 2007;369:1891–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60856-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians’ experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: Do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saulsbury FT, Campbell RE. Evaluation of child abuse reporting by physicians. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:393–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1985.02140060075033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada . Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2008: Major Findings. Ottawa: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaffin M, Kelleher K, Hollenberg J. Onset of physical abuse and neglect: Psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appleyard K, Berlin LJ, Rosanbalm KD, Dodge KA. Preventing early child maltreatment: Implications from a longitudinal study of maternal abuse history, substance use problems, and offspring victimization. Prev Sci. 2011;12:139–49. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0193-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:413–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu SS, Ma C-X, Carter RL, et al. Risk factors for infant maltreatment: A population-based study. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:1253–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall-Tackett K, Lyon T, Taliaferro G, Little L. Why child maltreatment researchers should include children’s disability status in their maltreatment studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:147–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotch JB, Browne DC, Dufort V, Winsor J. Predicting child maltreatment in the first 4 years of life from characteristics assessed in the neonatal period. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:305–19. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreat. 2003;8:334–49. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conron KJ, Beardslee W, Koenen KC, Buka SL, Gortmaker SL. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and child maltreatment in a national sample of families investigated by child protective services. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:922–30. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee BJ, Goerge RM. Poverty, early childbearing, and child maltreatment: A multinomial analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1999;21:755–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theodore A, Chang JJ, Runyan D. Measuring the risk of physical neglect in a population-based sample. Child Maltreat. 2007;12:96–105. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Psychiatric diagnoses of maltreated children: Preliminary findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:863–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–65. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Bellis MD. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:150–72. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bos K, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Drury SS, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA. Psychiatric outcomes in young children with a history of institutionalization. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19:15–24. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.549773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1223–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreat. 2009;14:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trocmé N, Knoke D, Fallon B, MacLaurin B. Differentiating between substantiated, suspected, and unsubstantiated maltreatment in Canada. Child Maltreat. 2009;14:4–16. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block RW, Krebs NF, American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and Committee on Nutrition Failure to thrive as a manifestation of child neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1234–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenny C, American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect Recognizing and responding to medical neglect. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1385–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hymel KP, American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect When is lack of supervision neglect? Pediatrics. 2006;118:1296–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyler DO, Horner SD. Family-centered collaborative negotiation: A model for facilitating behavior change in primary care. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:194–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123:858–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK model of pediatric primary care: Can child maltreatment be prevented in a low-risk population? Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:259–68. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barron CE, Jenny C. Definitions and categorization of child neglect. In: Jenny C, editor. Child Abuse and Neglect. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 539–43. [Google Scholar]