Abstract

Background

Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) contribute to carcinogenesis and cancer progression, although their origin and role remain unclear. We recently identified and investigated the in situ identity and implications of gastric submucosa-resident mesenchymal stem cells (GS-MSCs) in the progression of gastric carcinogenesis.

Methods

We isolated GS-MSCs from gastric submucosa using hydrogel-supported organ culture and defined their identity. Isolated cells were assessed in vitro by immunophenotype and mesengenic multipotency. Reciprocal interactions between GS-MSCs and gastric cancer cells were evaluated. To determine the role of GS-MSCs, xenografts were constructed of gastric cancer cells admixed with or without GS-MSCs.

Results

Isolated cells fulfilled MSCs requirements in regard to plastic adherence, stromal cell immunophenotype, and multipotency. We demonstrated a paracrine loop that gastric cancer cells enhanced the migration, proliferation, and differentiation of GS-MSCs; additionally, GS-MSCs promoted the proliferation of gastric cancer cell in vitro. Xenograft experiments showed that GS-MSCs significantly promoted cancer growth and angiogenesis. GS-MSCs that integrated into gastric cancer became not only CAFs but also rarely endothelial cells which contributed to the formation of cellular and vascular cancer stroma.

Conclusions

Endogenous GS-MSCs play an important role in gastric cancer progression.

Keywords: Gastric-resident mesenchymal stem cell, Carcinoma-associated fibroblast, Cancer stroma, Stomach neoplasms

All types of cancer require a specialized microenvironment, referred to the cancer stroma, for cancer initiation and progression.1 Carcinoma-associated fibroblast (CAF) is a primary cell type among heterogeneous stromal cell populations, although the origin of CAF is still ambiguous.2 The chemoattractants secreted by cancer guide migration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) to cancer tissues.3 Evidence indicates that recruited BM-MSCs contribute to carcinogenesis, progression, and angiogenesis by acting as progenitors for stromal cells.4

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are not restricted to bone marrow and are widely distributed in almost all tissues as tissue resident MSCs.5 Because tissue-resident MSCs retain a homing property to inflammatory or injured sites,6 they have a role in the development of cancer. Convincing evidence suggests that a subset of CAFs is derived from tissue-resident MSCs.7-9 Although a few studies have reported the existence of gastric-resident MSC-like cells, questions about their identity and role in gastric cancer remain to be defined.9,10

Invasive gastric carcinoma that extends beyond the mucosa often evokes a stromal reaction, which results in increased numbers of CAFs and a remodeled matrix compared to carcinoma in situ.11 Therefore, it is important to determine whether MSCs that reside endogenously in the stomach contribute to a specific role in gastric carcinogenesis. We previously demonstrated the existence of gastric submucosa-resident MSCs (GS-MSCs).12 In this study, we used a hydrogel-supported 3-dimensional (3D) organ culture to renew the tissue-resident MSCs population ex vivo, which was applied to isolate and define the MSC niche. This study worked to determine the in situ identity of GS-MSCs and their role in gastric carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

3D organ culture of gastric submucosa and isolation of outgrown cells

All gastric submucosa (GS) were obtained from brain-dead patients (n=12; 35 to 56 years; mean, 51 years). The procedure and guidelines were approved by the ethical committee at Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University School of Medicine. The GS was minced into 2 to 3 mm3 fragments, embedded in fibrin hydrogel, and cultured as described previously.5 After 14 days of organ culture, outgrown cells were selectively recovered from the hydrogel and propagated in a monolayer condition. When the cells reached confluence, they were detached and seeded at a density of 2×103 cells/cm2. This initial passage was referred to as passage 1. A limited dilution assay was performed to determine the clonogenic potential of recovered cells. The colony was counted using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) after 11 days of culture. All cell-based assays used subcultured outgrown cells at passage 3.

Localization and phenotype of in vitro renewed and outgrown cells

Paraffin sections including cultured GS fragments and outgrown cells were used to determine the in situ localization and phenotype of in vitrorenewed and outgrown cells during organ culture. Immunophenotype was determined with immunohistochemical staining using an EnVision detection system (Dako, Glosrup, Denmark) and diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).13 In situ localization of the renewed cells was evaluated using immunofluorescent staining and markers for endothelial cells (EC; CD31 and CD34), pericytes (CD140b and smooth muscle actin [SMA]), and MSCs (CD29 and CD105).14 The signals were visualized with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. All antibodies used in this experiment are listed in Table 1.

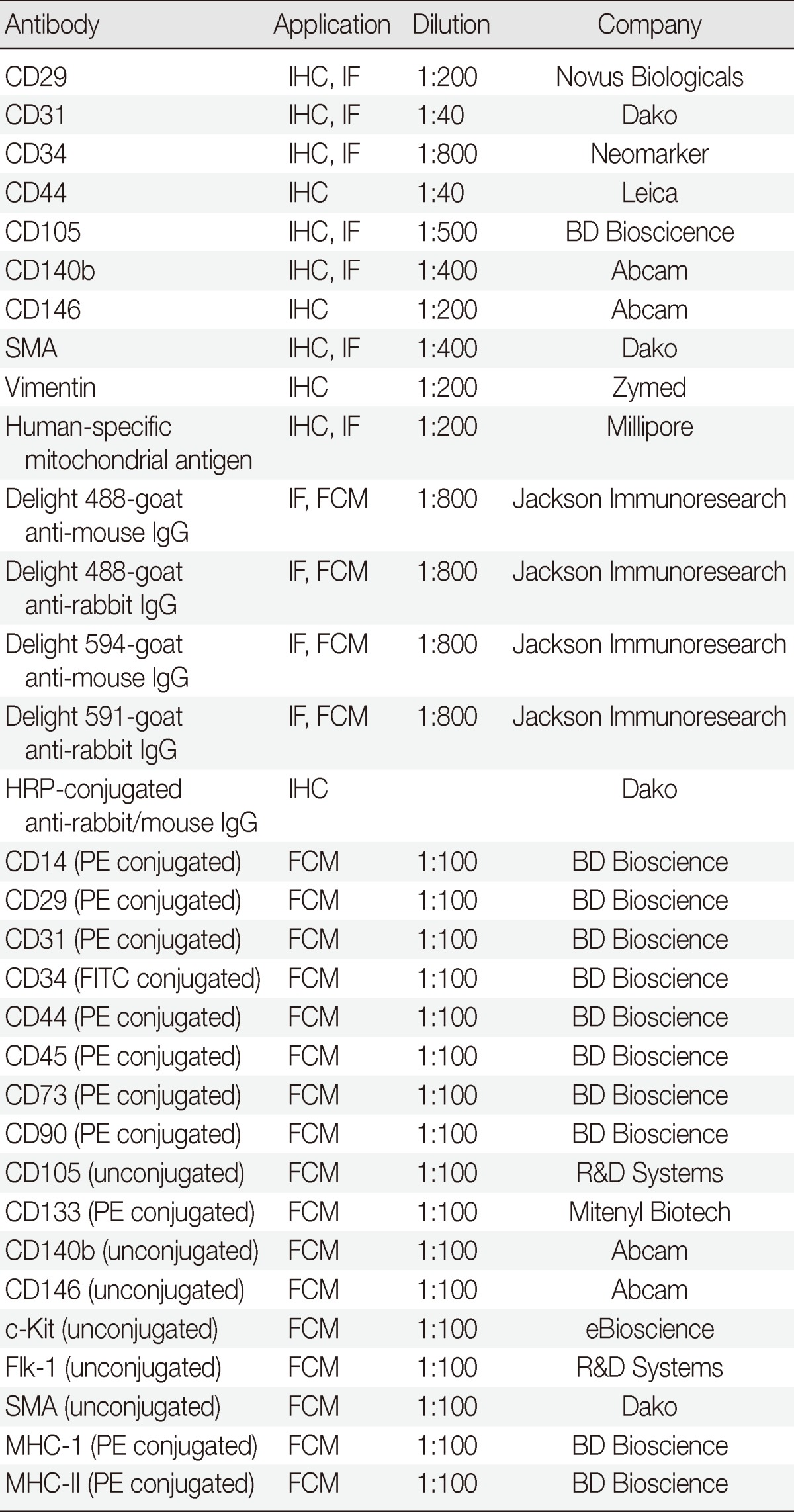

Table 1.

Antibodies used in the study

IHC, immunohistochemical staining; IF, immunofluorescent staining; SMA, smooth muscle actin; FCM, flow cytometry; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; PE, phycoerythrin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; MHC-I, major histocompatibility complex class I; MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex class II.

Flow cytometry analysis

The immunophenotype of the subcultured cells was analyzed with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). After the cells were incubated with primary or isotype-matched antibodies, the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and fixed. For unconjugated antibodies, the signal was detected after incubation with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. Isotype-matched immunoglobulin was used as a negative control. A minimum of 10,000 events were acquired for each analysis.

In vitro mesengenic differentiation

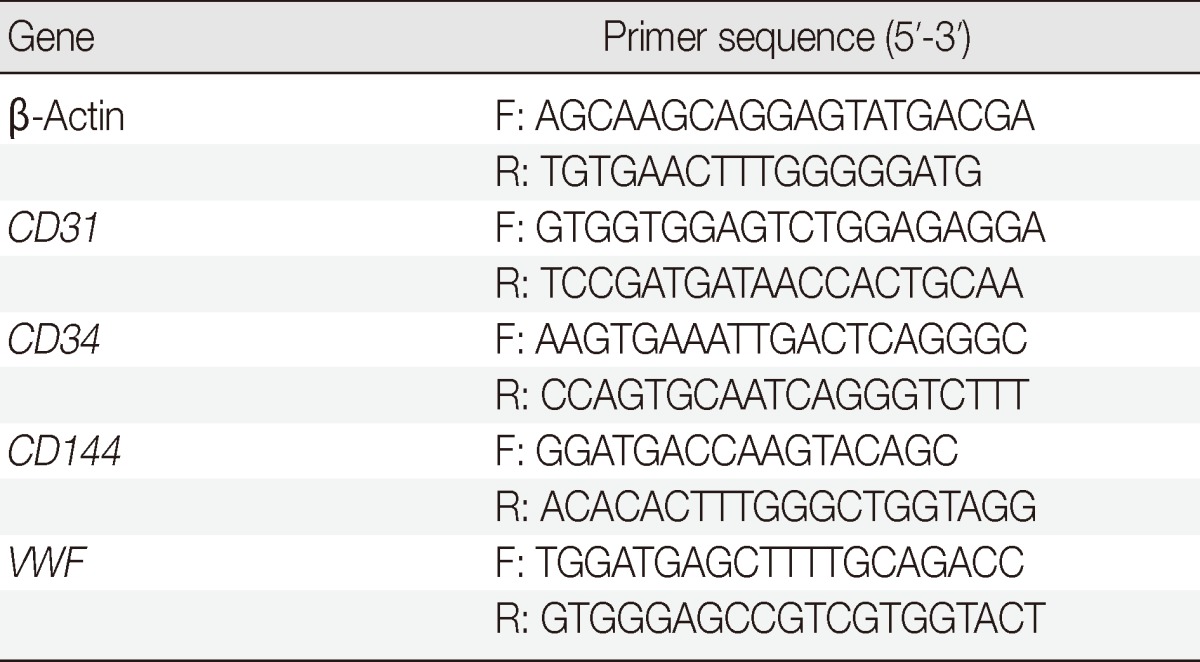

Subcultured cells were induced into adipogenic and osteogenic cells as described previously.5 Adipogenic or osteogenic differentiation was determined with Oil Red O (Sigma) or Alizarin Red (Sigma) stainings, respectively. To determine the EC differentiation potential, subcultured cells were seeded on fibrin hydrogel and induced with 20 ng/mL vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or conditioned media. Endothelial cell differentiation was determined by capillary-like network formation and expression of EC-specific markers. The tube length and the branching points of the capillary-like structure were measured with the photoplanimetric method using Image J (NIH). The expression of EC-specific proteins and mRNAs was determined by immunofluorescent staining and by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, respectively. The primers used in this experiment are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in the study

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Conditioned media

All gastric cancer cell lines including AGS, NCI-N87, and SNU-1 were purchased from Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). When the cancer cells or GS-MSCs reached 80% confluence, the cells were washed three times with Dulbecco's modified Eagle media (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and incubated with vehicle (99% DMEM and 1% calf serum) for 12 hours. Conditioned media comprised of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) and HEK293 were used as positive or negative controls, respectively.

In vitro scratch assay

A confluent monolayer of GS-MSCs on 60-mm dishes was scraped with a p200 pipet tip to create a straight scratch line. The debris was removed by washing with vehicle media, conditioned media were added, and then the cells were cultured for 24 hours. The photoplanimetric method was used to measure the migration distance with Image J. The mitogenic effect of gastric cancer cells on GS-MSCs was determined by measuring the DNA content using PicoGreen dsDNA quantitation kit (Invitrogen) after the cells were incubated for three days with conditioned gastric cancer cell line media.

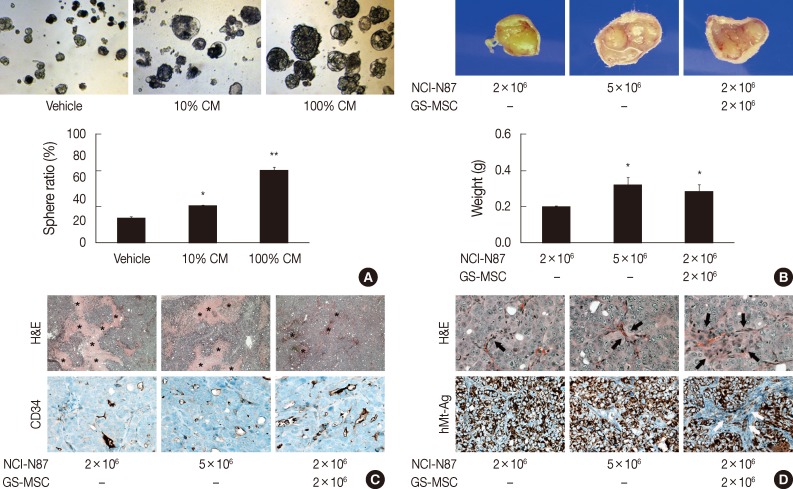

In vitro tumor sphere formation assay

NCI-N87 cells (1×104) were suspended in vehicle, 10% or 100% conditioned media of GS-MSCs, transferred into each well of an ultra-low attachment 12-well plate (Coring, Lowell, MA, USA), and cultured for 12 days. The sphere ratio was calculated as the percentage of the sphere with more than 100 µm of diameter to the total sphere number.

Xenograft transplantation

The xenograft animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Review Committee of Inje University School of Medicine. Athymic nude mice (Balb/c nu/nu, 6 weeks old, female, n=20) were used for the procedure, and NCI-N87 cells (2×106) admixed with or without GS-MSCs (2×106) or 5×106 NCI-N87 cells were injected subcutaneously. Tumorigenesis was assessed daily with macroscopic observation. Three weeks after the injection, the formed tumor was dissected, and its weight was measured. To evaluate the general features and CD34+ microvascular density, hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry were performed. Double immunostaining against a human-specific mitochondrial antigen (hMt-Ag) and ECs and CAFs markers was performed to determine the role of the transplanted GS-MSCs. The signals were visualized with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. Isotype-matched immunoglobulin was used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the SPSS ver. 10.0.7 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. A p<.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

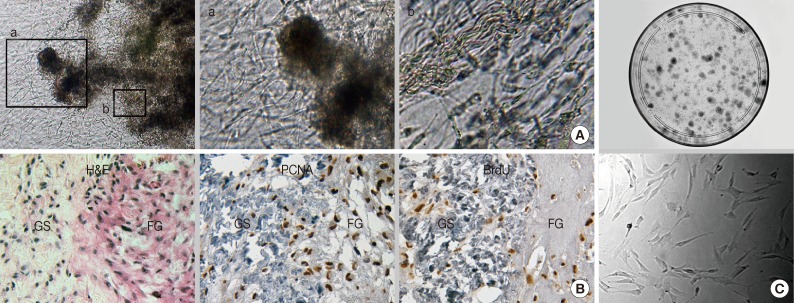

In situ renewed and outgrown cells showed MSC-like phenotypes

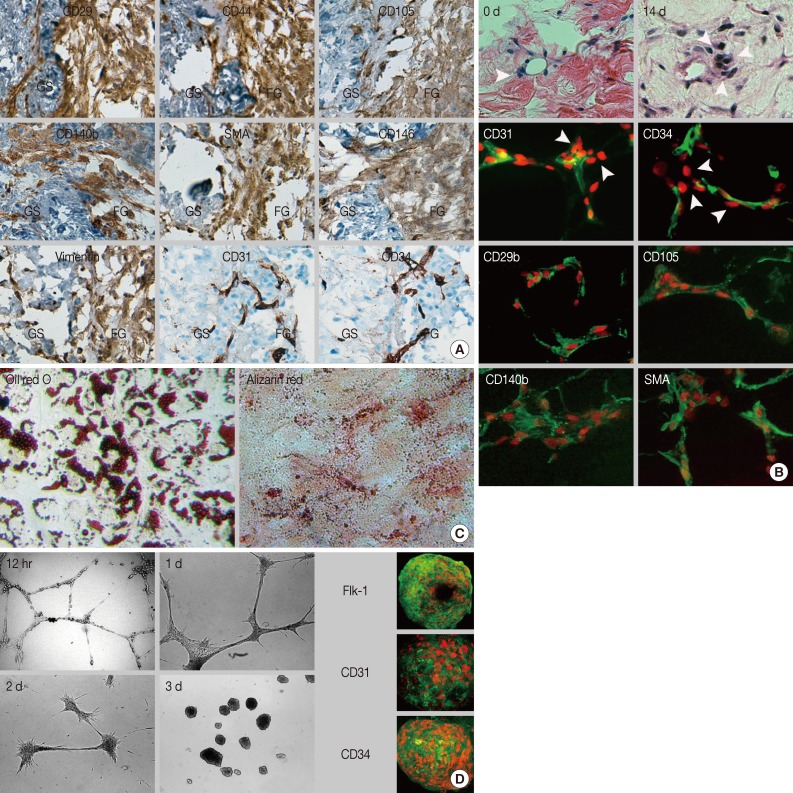

The sol-gel phase transitional hydrogel provided physical support for GS fragments and a large surface area for outgrowth of the in vitro renewed cells residing in the GS. Outgrown cells were recognized on day 1 of culture; thereafter, these cells proliferated extensively and distributed in the fibrin hydrogel and within the GS (Fig. 1A). Most of the outgrown cells that had a spindle-shape appearance expressed or incorporated proliferating cell nuclear antigen or bromodeoxyuridine, which indicated that these cells were derived from in vitro cell division (Fig. 1B). After 14 days of culture, outgrown cells were successfully recovered from the hydrogel after urokinase treatment. Recovered cells were rapidly attached and spread on the plastic dish within 30 minutes. The limited dilution assay showed that more than 15% of the recovered cells that formed colonies were composed of homogeneous fibroblastoid cells (Fig. 1C). Outgrown cells uniformly expressed a set of MSC markers including CD29, CD44, and CD105 (Fig. 2A). Moreover, these cells expressed pericyte markers including CD140b, CD146, and α-SMA, but no EC markers (CD31 and CD34) or hematopoietic cell markers (CD34 and CD45, data not shown) were observed, indicating that outgrown cells showed MSC-and pericyte-like phenotypes. Next, we determined where the cells resided in the GS. The cell density within the GS increased around the perivascular area of microvessels that did not have a mural layer after 14 days of organ culture (Fig. 2B). Immunostaining demonstrated that the in vitro renewed cells increased around CD31+ and CD34+ microvessels. These cells did not express EC markers but consistently expressed MSC and pericyte markers. Our results suggest that perivascular MSC-like cells were predominantly renewed during the in vitro culture and outgrew into the hydrogel, indicating that the origin of the outgrown cells was a specific population of microvascular pericytes residing in the GS.

Fig. 1.

Fibrin hydrogel-supported 3-dimensional organ culture of the gastric submucosa (GS). (A) Phase-contrast microphotographs show robust cell outgrowth into the hydrogel from the embedded GS. High-power observation discloses outgrown cells with the fibroblastoid feature in the hydrogel (a) and in situ renewed cells inside of the GS (b). (B) After two weeks of organ culture, the number of cells increases in the fibrin hydrogel (FG) and the GS. Most cells express or incorporate proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) or bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). (C) The limited dilution assay indicates the highly clonogenic potential of recovered outgrown cells from the hydrogel with fibroblastoid morphology. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Fig. 2.

The immunophenotype, localization, and differentiation potential of in situ renewed and outgrown cells. (A) Immunohistochemical staining reveals that outgrown cells express mesenchymal stem cell markers and pericyte markers but do not express endothelial cell markers. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows increased cell density around the microvessels at day 14 of culture compared to day 0. Immunofluorescent staining shows perivascular localization of in situ renewed cells with a mesenchymal stem cell-and pericyte-like phenotype. (C, D) Nuclei are counterstained with propidium iodide (red). Subcultured outgrown cells show differentiation potential into adipogenic (C, Oil red O), osteogenic (C, Alizarin red), and endothelial cells (D). Cells induced with vascular endothelial growth factor form a capillary-like network at 12 hours. Then, cells aggregate with each other to form a spheroid structure at day 3 and express FIk-1, CD31, and CD34. SMA, smooth muscle actin; GS, gastric submucosa; FG, fibrin hydrogel.

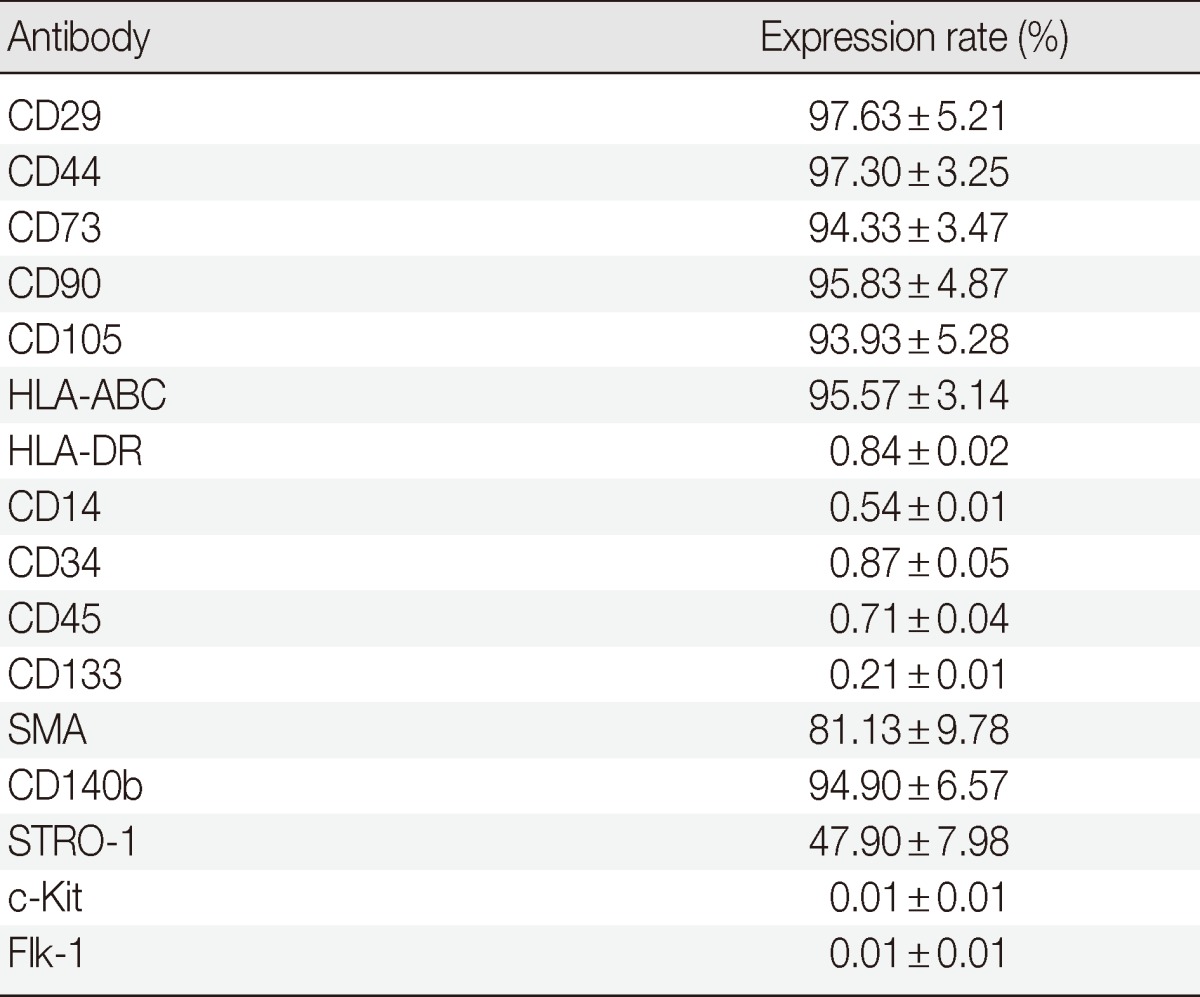

Subcultured outgrown cells exhibit typical MSC properties

Regardless of tissue origin, MSCs are defined by stromal cell immunophenotype and multipotency which are categorized into mesodermal lineages. This study determined whether in vitro subcultured outgrown cells fulfilled these requirements. The outgrown cells rapidly adhered and showed typical fibroblastic features once seeded on cultured plastic. Subcultured cells did not show any alterations in the initial immunophenotype observed for the in situ renewed and outgrown cells. Additionally, more than 90% of the cells consistently expressed MSC markers, such as CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105, and expressed pericyte markers at variable frequencies, indicating the MSC-and pericyte-like immunophenotypes were maintained after in vitro expansion (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expression rate of the surface markers analyzed with flow cytometry

SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Subcultured cells showed cytoplasmic accumulation of fat droplets and mineral crystal deposition in response to the defined culture conditions, which indicated that the cells retained adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential (Fig. 2C). MSCs have been considered as tissue-resident endothelial progenitor cells due to their ability to differentiate toward ECs.15 The subcultured outgrown cells induced by VEGF formed a capillary-like structure within 12 hours (Fig. 2D), which indicated angiogenic potential. Next, the capillary-like structure disassembled, and the outgrown cells aggregated and transformed into a sphere-like structure at three days. Interestingly, when the spheres formed, the outgrown cells expressed EC markers (Flk-1, CD31, and CD34), indicating EC differentiation potential. Collectively, our results indicated that the outgrown cells from the GS fulfilled the minimum requirement of MSCs in terms of plastic adherence, stromal cell immunophenotype, and multipotency.

Gastric cancer cells enhance GS-MSC migration, proliferation, and endothelial differentiation

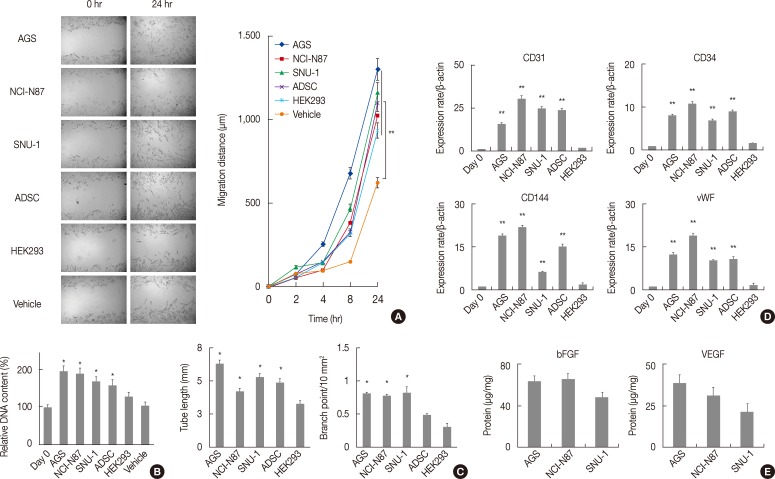

Evidence indicates that the reciprocal interaction between cancer cells and BM-MSCs is important in carcinogenesis.16 However, the reciprocal interactions between gastric-resident MSCs and gastric cancer cells have not been elucidated. The in vitro migration assay revealed that conditioned gastric cancer cell line media significantly increased GS-MSC migration (p<.01) (Fig. 3A) and the proliferation of GS-MSCs (p<.05) (Fig. 3B) compared to vehicle.

Fig. 3.

Paracrine effects of gastric cancer cells on gastric submucosa-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GS-MSCs). Conditioned gastric cancer cell line media (AGS, NCI-N87, and SNU-1), adipose-derived stem cells (ADSC), and HEK293 are used. (A) GS-MSCs migration do not significantly increased in cells incubated with conditioned gastric cancer cell media. **p<.01 compared to vehicle. (B) Cell proliferation increases meaningfully in GS-MSCs incubated with the conditioned gastric cancer cell media. *p<.05 compared to vehicle. (C) The tube length and branch point of capillary-like network significantly increase in GS-MSCs induced by conditioned gastric cancer cell media. *p<.05 compared to HEK293. (D) Endothelial cell-specific mRNAs measured with quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction are highly expressed in GS-MSCs induced by conditioned gastric cancer cell media. vWF, von Willebrand factor. **p<.01 compared to HEK293. (E) Quantitative analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) contents with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in conditioned gastric cancer cell line media.

Since angiogenesis is critical for tumorigenesis, cancer cells secrete proangiogenic factors that directly or indirectly contribute to neovascularization. Therefore, we determined the effects of gastric cancer cells on GS-MSCs EC differentiation. All conditioned gastric cancer cell line media and ADSCs enabled GS-MSCs to form a capillary-like structure (data not shown). However, HEK293 vehicle or conditioned media did not form capillary-like structures. In addition, the tube length and the number of branch points of the capillary-like network were significantly higher in cells induced by conditioned gastric cancer cell line media than in conditioned HEK293 media (p<.01) (Fig. 3C).

Next, we investigated the EC-specific mRNA expression levels in induced GS-MSCs with conditioned gastric cancer cell line media. Interestingly, GS-MSCs induced by conditioned gastric cancer cell media showed significantly higher EC-specific mRNA expression of CD31, CD34, CD144, and von Willebrand factor compared to GS-MSCs before induction or those induced by conditioned HEK293 media (Fig. 3D). However, no meaningful difference in the EC-specific mRNA expression level was observed according to gastric cancer cell type. VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) play important roles in mobilization and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells, and immunoabsorbent analysis showed that the VEGF and bFGF were detected in all conditioned gastric cancer cell line media but not in conditioned HEK293 media. This indicates that proangiogenic factors secreted by gastric cancer cells might directly induce GS-MSCs toward ECs (Fig. 3E).

GS-MSCs promote tumor growth and angiogenesis

Although our data indicated chemotactic and mitotic effects of gastric cancer cells on GS-MSCs, whether GS-MSCs play specific roles in gastric cancer is unclear. The tumor sphere-forming assay indicated that GS-MSC had a mitogenic effect on the growth of gastric cancer cells (Fig. 4A). Conditioned GS-MSC medium dose-dependently enhanced NCI-N87 tumor sphere formation. Next, we investigated the role of GS-MSCs in tumorigenesis and progression in vivo. All mice injected with 5×106 NCI-N87 only showed de novo tumor formation at one week, but mice injected with 2×106 NCI-N87 had late-forming tumors at two weeks. The tumor volume was related to the number of NCI-N87 injections in a dose-dependent manner at three weeks (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, tumors in mice injected with 2×106 NCI-N87 and 2×106 GS-MSCs were detected earlier, at one week. The size and weight of the tumors were significantly higher in mice injected with both NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs compared to those of mice injected with 2×106 NCI-N87 only (p<.01). However, GS-MSCs did not induce de novo tumor formation by non-tumorigenic gastric cancer cells, such as AGS, until 12 weeks of observation (data not shown). These data suggest that GS-MSCs can accelerate cancer growth but not cancer initiation.

Fig. 4.

The effect of gastric submucosa-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GS-MSCs) on the growth of gastric cancer cells. (A) Conditioned GS-MSCs media (CM) enhances in vitro tumor spheroid formation of NCI-N87 in a dose-dependent manner. *p<.05 and **p<.01 compared to vehicle. (B) The weight of the tumor measured at three weeks post-injection increases in mice injected with NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs. *p<.05 compared to NCI-N87 (2×106 cells). (C) Tumors formed by injection of NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs show decreased coagulative necrosis (asterisk) but increased CD34+ microvascular density compared to tumors formed by injection of NCI-N87 only. (D) Tumors formed by injection of NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs show increased cellular and vascular stroma (arrow, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]) compared to tumors formed by injection of NCI-N87 only. Human-specific mitochondrial antigen (hMt-Ag) is uniformly expressed in all cancer cells, but hMt-Ag+ stromal cells (arrows) are detected in tumors formed by NCI-N87 and GS-MSC injections.

De novo formed tumors exhibited typical features of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma regardless of GS-MSC injection (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, tumors formed by NCI-N87 and GS-MSC coinjections showed decreased coagulative necrosis compared to tumors formed by injection of NCI-N87 only (Fig. 4C). The CD34+ microvascular density was significantly increased in tumors injected with NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs (2.79/mm2) compared to tumors injected with 2×106 (1.87/mm2) and 5×106 (1.95/mm2) NCI-N87, respectively (p<.05). Intriguingly, the cancer stroma formed by coinjection of NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs showed increased cellularity and vascularity compared to the cancer stroma formed by injection of NCI-N87 only (Fig. 4D).

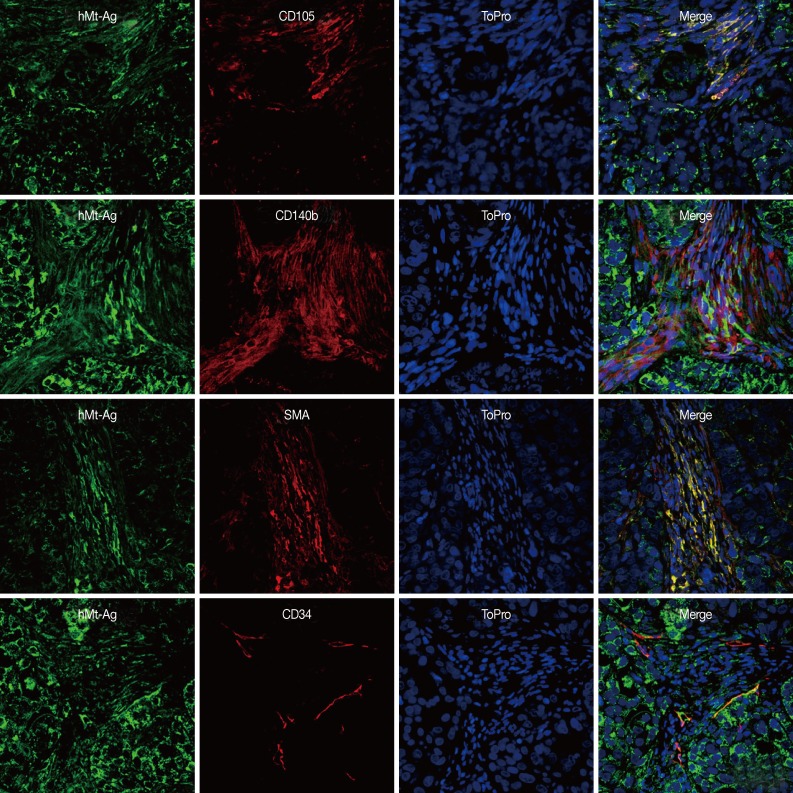

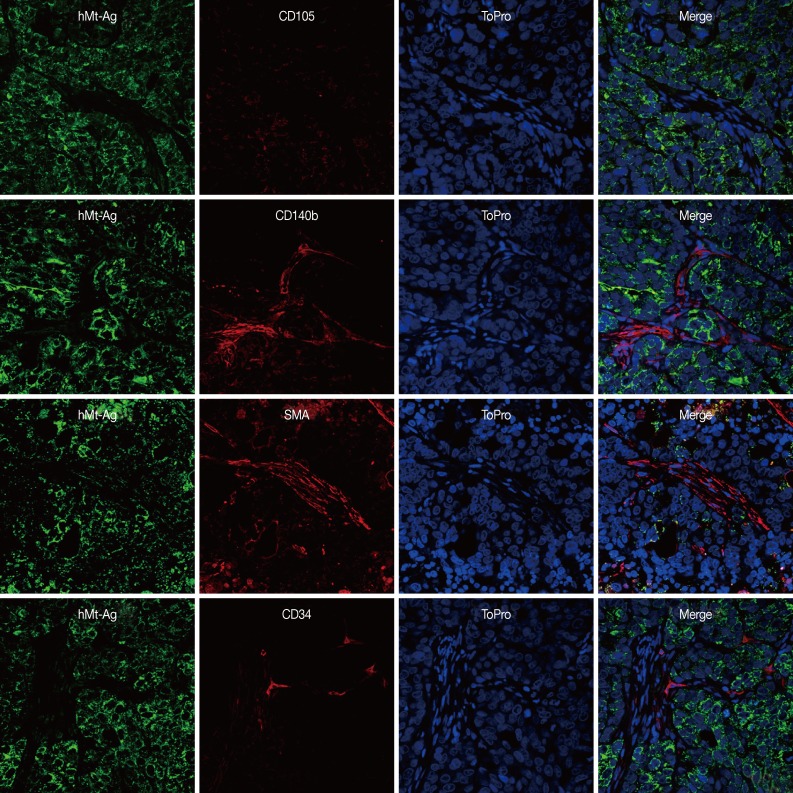

GS-MSCs directly integrate into tumor stroma and become SMA+ CAFs

To investigate the role of GS-MSCs in gastric cancer, we traced the injected cells using hMt-Ag. All cancer cells homogeneously expressed hMt-Ag in their cytoplasm, but hMt-Ag tracing did not detect intervening cancer stroma formed by NCI-N87-only injections. More than 20% of the cancer stromal cells formed by NCI-N87 and GS-MSC coinjections expressed hMt-Ag.

We performed double immunostaining to determine the role of the injected GS-MSCs. hMt-Ag+ stromal cells were widely distributed along the cancer stroma and coexpressed CD105, CD140b, and SMA (Fig. 5). The analysis indicated that approximately 20% of hMt-Ag+ stromal cells coexpressed SMA. Occasionally, hMt-Ag+ stromal cells coexpressing CD34 were observed in the intraluminal side of microvessels in the cancer stroma, but less than 1% of CD34+ ECs were observed to demonstrate this coexpression. However, the cancer stroma formed by an injection of NCI-N87 alone were not localized with any hMt-Ag+ stromal cells (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results indicate that locally delivered GS-MSCs were integrated into the cancer stroma where GS-MSCs become SMA+ CAFs but rarely microvascular ECs, which contributed to the cancer stroma and gastric cancer angiogenesis.

Fig. 5.

The contribution of gastric submucosa-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GS-MSCs) to the formation of cancer stroma. Immunofluorescent staining reveals that human-specific mitochondrial antigen (hMT-Ag)+ stromal cells coexpress CD105, CD140b, and smooth muscle actin (SMA) and are easily observed in the cancer stroma formed by co-injection of NCI-N87 and GS-MSCs, but hMT-Ag+/CD34+ endothelial cells are rarely observed. Nuclei are counterstained with ToPro.

Fig. 6.

Representative microphotographs of double immunostaining against human-specific mitochondrial antigen and stromal cell markers (CD105, CD140b, and smooth muscle actin [SMA]) and endothelial cells (CD34) in the cancer stroma formed by injection of NCI-N87 only. hMT-Ag, human-specific mitochondrial antigen. Nuclei are counterstained with ToPro.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have indicated that various cancers can attract MSCs in their microenvironment, and that MSCs become CAFs and play a role in tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and progression. However, most of these studies described the roles of BM-MSCs.16-18 In this study, we demonstrated the existence of endogenous gastric-resident MSCs and their role in gastric cancer.

Evidence suggests that MSCs reside in a perivascular niche, where they are in close proximity to ECs of microvessels.5 This evidence illustrates that the degree of microvascular density is closely related to the MSC density. Thus, we speculated that the GS might retain a higher density of MSCs compared to other compartments of the stomach due to their high vascularity. The results demonstrate that in situ renewed cells were apparent in perivascular locations in the GS and consequently outgrew in the hydrogel. Both in situ and subcultured outgrown cells shared typical biologic properties with BM-MSCs. Collectively, our data support not only the perivascular MSC hypothesis, but also the existence of gastric-resident MSCs residing in the GS. Additionally, our results suggest the possibility that tissue-resident MSCs are not restricted to the stomach but might be widely distributed in other areas of the intestinal tract.

Cancer growth is determined by crosstalk between cancer cells and stromal cells.17 Our in vitro results demonstrate a paracrine loop in which gastric cancer cells exert migration and proliferation of GS-MSCs, and, in response, GS-MSCs subsequently play an important role in gastric cancer growth and angiogenesis. Proangiogenic factors secreted by gastric cancer cells, such as VEGF and bFGF, further induced GS-MSC EC differentiation in vitro. Meanwhile, GS-MSCs also facilitated not only in vitro tumor spheroid formation, but also enhanced in vivo tumor growth. Collectively, our results indicate that a reciprocal interaction between gastric cancer cells and GS-MSCs is exerted synergistically in gastric cancer.

CAFs are thought to develop from both local and distant niches and to provide a functional and structural supportive microenvironment for cancer. A number of studies have indicated that tissue-resident MSCs integrate into cancer sites and contribute to the formation of cancer stroma in various types of cancer.7-9 Although a few studies have elucidated the existence of MSC-like cells in the stomach, the contributions of gastric-resident MSCs in gastric cancer are less well known.9,10 Our results demonstrated that tumors with admixed GS-MSCs showed hMt-Ag positive stromal cells that coexpressed with CD105, CD140b, SMA, and CD34, indicating that GS-MSCs can give rise to a set of stromal cell populations, including CAFs and ECs. Therefore, GS-MSCs constitute an important cell source for CAFs in that they promote gastric cancer growth through the formation of fibrovascular stroma.

Promoting angiogenesis is an important function of MSCs during wound healing as well as carcinogenesis.19,20 MSCs promote angiogenesis through the expression of SDF-1 and VEGF, which mobilize ECs and/or endothelial progenitor cells.21 Moreover, MSCs can directly give rise to angiogenic cells both in vitro and in vivo.22 Thus, a specific population of MSCs has been regarded as tissue-resident endothelial progenitor cells. Our data indicate that gastric-resident MSCs also contribute to direct and indirect promotion of tumor angiogenesis since the CD34+ microvascular density was significantly increased in tumors with admixed GS-MSCs. Although our results indicate that GS-MSCs can differentiate into ECs in vitro, the frequency of CD34+/hMt-Ag+ ECs was less than 1% among the CD34+ ECs of the microvessels, indicating that the proangiogenic ability of GS-MSCs is most likely induced by an indirect mechanism.

In summary, we showed that gastric-resident MSCs exist in the GS. These cells reciprocally interact with cancer cells to promote the growth and progression of gastric cancer. Similar to BM-MSCs, gastric-resident MSCs actively integrated, became SMA+ CAFs and CD34+ ECs, and contributed to the formation of the fibrovascular cancer stroma. These observations have implications for gastric cancer progression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mid-Carrier Researcher Program (NRF 2009-0060244 and NRF 2012-046885) and the NanoBio R&D Program (2008-01163) of the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning & National Research Foundation of Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes: bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Direkze NC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jeffery R, et al. Bone marrow contribution to tumor-associated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8492–8495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Silva Meirelles L, Caplan AI, Nardi NB. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287–2299. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muehlberg FL, Song YH, Krohn A, et al. Tissue-resident stem cells promote breast cancer growth and metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:589–597. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin G, Yang R, Banie L, et al. Effects of transplantation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells on prostate tumor. Prostate. 2010;70:1066–1073. doi: 10.1002/pros.21140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomoto-Kojima N, Aoki S, Uchihashi K, et al. Interaction between adipose tissue stromal cells and gastric cancer cells in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;344:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X, Zhang X, Wang S, et al. Isolation and comparison of mesenchymal stem-like cells from human gastric cancer and adjacent non-cancerous tissues. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0908-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semba S, Kodama Y, Ohnuma K, et al. Direct cancer-stromal interaction increases fibroblast proliferation and enhances invasive properties of scirrhous-type gastric carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1365–1373. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi MY, Kim HI, Yang YI, et al. The isolation and in situ identification of MSCs residing in loose connective tissues using a niche-preserving organ culture system. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4469–4479. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang TJ, Kim SW, Lee KS. The expression of pigment epithelium-derived factor in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:261–265. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung YH, Kim J, Kim BM, et al. Neoplastic stromal cells of intracranial hemangioblastomas disclose pericyte-derived mesenchymal stromal cells-like phenotype. Korean J Pathol. 2011;45:564–572. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res. 2004;95:343–353. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137877.89448.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuiffo BG, Karnoub AE. Mesenchymal stem cells in tumor development: emerging roles and concepts. Cell Adh Migr. 2012;6:220–230. doi: 10.4161/cam.20875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keung EZ, Nelson PJ, Conrad C. Concise review: genetically engineered stem cell therapy targeting angiogenesis and tumor stroma in gastrointestinal malignancy. Stem Cells. 2013;31:227–235. doi: 10.1002/stem.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki K, Sun R, Origuchi M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells promote tumor growth through the enhancement of neovascularization. Mol Med. 2011;17:579–587. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foronjy RF, Majka SM. The potential for resident lung mesenchymal stem cells to promote functional tissue regeneration: understanding microenvironmental cues. Cells. 2012;1:874. doi: 10.3390/cells1040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torsney E, Xu Q. Resident vascular progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]