Abstract

L-arginine-L-aspartate is widely used by athletes for its potentially ergogenic properties. However, only little information on its real efficacy is available from controlled studies. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of prolonged supplementation with L-arginine-L-aspartate on metabolic and cardiorespiratory responses to submaximal exercise in healthy athletes by a double blind placebo-controlled trial. Sixteen healthy male volunteers (22 ± 3 years) performed incremental cycle spiroergometry up to 150 watts before and after intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate (3 grams per day) or placebo for a period of 3 weeks. After intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate, blood lactate at 150 watts dropped from 2.8 ± 0.8 to 2.0 ± 0.9 mmol·l-1 (p < 0.001) and total oxygen consumption during the 3-min period at 150 watts from 6.32 ± 0.51 to 5.95 ± 0.40 l (p = 0.04) compared to placebo (2.7 ± 1.1 to 2.7 ± 1.4 mmol·l-1; p = 0.9 and 6.07 ± 0.51 to 5.91 ± 0.50 l; p = 0.3). Additionally, L-arginine-L-aspartate supplementation effected an increased fat utilisation at 50 watts. L-arginine and L-aspartate seem to have induced synergistic metabolic effects. L-arginine might have reduced lactic acid production by the inhibition of glycolysis and L-aspartate may have favoured fatty acid oxidation. Besides, the results indicate improved work efficiency after L-arginine-L-aspartate intake. The resulting increases of submaximal work capacity and exercise tolerance may have important implications for athletes as well as patients.

Key Points.

Amino acids are among the most common nutritional supplements taken by athletes. They are involved in numerous metabolic pathways that affect exercise metabolism.

Three weeks of L-arginine-L-aspartate supplementation resulted in lower blood lactate concentrations and oxygen consumption, diminished glucose and enhanced fat oxidation, and reduced heart rate and ventilation during submaximal cycle exercise.

This implies increased submaximal work capacity and exercise tolerance, which may have important implications for both athletes as well as patients.

Key Words: Nutrition, supplementation, amino acids, ergogenic, performance

Introduction

Amino acids are among the most common nutritional supplements taken by athletes. They are involved in numerous metabolic pathways that affect exercise metabolism. Although it is likely that amino acids play important anaplerotic functions during exercise and recovery sustaining the metabolic process, there is little evidence from controlled studies for ergogenic benefits of amino acid ingestion (Brooks, 1987; Hargreaves and Snow, 2001; Kreider et al., 1993). For example, the supplementation of branched-chain amino acids and glutamine were shown to have little or no effect on performance (Davies, 1995; Gastmann and Lehmann, 1998; Kreider, 1998). In contrast, impressive effects on the performance of endurance exercises in the field have been reported after prolonged intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate (Schmid et al., 1980; Sellier, 1979). However, these studies did not use standardised test procedures to evaluate the influence of L- arginine-L-aspartate on performance and associated cardiovascular and metabolic responses. L- arginine, a precursor of nitric oxide, was shown to decrease exercise-induced blood lactate concentrations (Gremion et al., 1989) and to improve the management of multiple cardiovascular diseases by correcting endothelial dysfunction (Ceremuzynski et al., 1997; Cheng and Balwin, 2001). But most published reports on humans are based on studies of small numbers of subjects and do not allow definitive recommendations. A recently published animal study confirmed that L-arginine supplementation augments aerobic capacity, particularly under conditions where endothelium-derived nitric oxide (EDNO) activity is reduced (Maxwell et al., 2001). The authors demonstrated enhanced exercise-induced EDNO synthesis and aerobic capacity after L- arginine supplementation also in healthy animals. If this holds true for humans, important conclusions could be derived that might also be applicable for athletes. Beside a possible effect on exercise-induced hyperaemia (Lau et al., 1998), nitric oxide was shown to modulate muscle metabolism including glucose uptake, glycolysis and mitochondrial oxygen uptake (Reid, 1998). L-aspartate, a precursor of oxaloacetate, was supposed to increase the utilisation of free fatty acids (FFA) and to spare muscle glycogen (Lancha et al., 1995). Additionally, L-aspartate increased the peripheral clearance of ammonia (Denis et al., 1991) with the consequence of delayed muscle fatigue and increased endurance performance. Although the effects of these two amino acids have been supposed to be synergistic, little is known on their impact on endurance performance. Our previous observations (Brunner et al., 2003) and the findings of Schmid et al. (1980) and Sellier (1979) suggest that L-arginine-L-aspartate seems especially to impinge on low-intensity exercise in particular and, that prolonged supplementation rather than short-term intake seems to stabilise beneficial changes of exercise metabolism. We therefore evaluated the effects of the prolonged supplementation of L-arginine-L-aspartate on metabolic and cardiorespiratory responses to submaximal exercise in healthy athletes.

Methods

Subjects

Male sport students of the University of Innsbruck were invited to participate in the study. Criteria for exclusion were acute or chronic illnesses, regular use of drugs or preparations of amino acids, regular smoking (> 3 cigarettes per day), abnormal results concerning exercise responses, counts of red and white blood cells and biochemical parameters of renal and liver function. Finally, sixteen participants (22 ± 3 years) were randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to the L-arginine-L-aspartate group (AG) or to the placebo group (PG). Baseline characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1. Members of the PG were rather occasional smokers than those of the AG, but none of them did smoke more than 20 cigarettes per week. The members of the PG tended to be more physically active at a lower intensity compared to the AG. The products of duration and intensity, however, were the same for both groups. Baseline exercise testing (cycle ergometry) revealed a maximum oxygen uptake of about 50 ml·min-1·kg-1 for both groups. Participants performed their usual physical activities throughout the study. They were asked not to change their patterns of nutrition and sleep. Physical activity, nutrition, sleeping and well being of each participant were recorded on a daily basis. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Innsbruck.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the L-arginine-L-aspartate and the placebo group. Data represent means (±SD) or frequencies.

| PLACEBO (n=8) |

L-ARGININE- L-ASPARTATE (n=8) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 21.0 (1.8) | 22.4 (3.9) |

| Height (m) | 1.81 (.08) | 1.80 (.07) |

| Body mass (kg) | 75.5 (11.6) | 72.5 (6.5) |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 79.6 (11.6) | 77.0 (12.7) |

| Resting systolic BP (mmHg) | 127.4 (20.8) | 133.8 (16.2) |

| Resting diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 76.0 (8.6) | 77.4 (18.1) |

| Occasional smokers, n (%) | 4 (50) | 2 (25) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Duration (h·week-1) | 14.8 (7.3) | 11.4 (4.4) |

| Intensity* (1-3) | 1.8 (0.7) | 2.2 (0.6) |

* Intensity 1-3: 1 = low, 2 = moderate, 3 = high.

Exercise testing

In our previous pilot study which was not placebo-controlled (Brunner et al. 2003), we found that highly impressive effects occurred below the anaerobic threshold. For this reason, we decided to use a submaximal exercise test in the present investigation. Incremental submaximal cycle spiroergometry was performed before (pre-test) and after 3 weeks (re-test) of intake of L-arginine- L-aspartate or placebo. Re-tests were performed on the last day of the intake of the preparation. Tests were carried out in the late morning and early afternoon not less than 2 hours after a light meal. No intense physical activity was permitted during the 2 days prior to the tests and smoking was not allowed on the days of exercise testing. Cycle adjustments were the same for both tests. Before starting the exercise test, subjects rested for 5 minutes in a sitting position on the cycle ergometer (Ergoline 900, Schiller, Switzerland). The initial intensity of 50 watts was increased by 50 watts every 3 minutes up to 150 watts. Pedalling frequency was held constant at 70 rpm. Gas exchange and heart rate (Oxycon Alpha, Jaeger, Germany) were recorded continuously. The gas analysis system has been calibrated before each test. Blood pressure was measured at the end of each workload.

Blood samples (20 µl), from an earlobe, were collected at the end of the workloads of 100 watts and 150 watts and the whole blood samples were analysed enzymatically for blood lactate concentration with a Biosen 5040 apparatus (EKF Industrie, Barleben, Germany).

Temperature in the laboratory room was about 26 degrees Celsius and relative humidity was about 60 %. All participants had been familiarised with the test procedures prior to the study.

Administration of L-arginine-L-aspartate

After exercise testing, participants received 60 5 ml ampoules, each containing 1 g of L-arginine-L- aspartate (in saccharose solution) or placebo (saccharose solution), which were identical in appearance and similar in taste (Certificate of analysis: Laboratoire Sarget, Cedex, France). Subjects were instructed to take 3 ampoules orally per day (morning, noon, evening) for 20 consecutive days. The regular intake was documented in the protocol. The chosen dose and the duration of intake are common among athletes. Because of organizational considerations (5 ml ampoules, double-blind experiment) dosing was not adjusted for body mass. The efficiency of L- arginine-L-aspartate supplementation, especially regarding nitric oxide production, was confirmed in our not-placebo controlled pilot project (Brunner et al., 2003) by measuring urine nitrate excretion and blood glucose. For this reason we did not repeat these measurements in the present investigation.

Statistics

Data are presented as means (±SD). From the continuous monitoring during exercise tests, averages of the last 30 seconds of each workload were used to calculate mean values.

Physical work capacity at the heart rate of 130 beats·min-1 was calculated by intrapolation on the individual power-to-heart rate curves. Total oxygen consumption of the 3-min period at 150 watts was calculated by the area under the curve. Paired t-tests were used for the comparison of continuous variables within groups and unpaired t-tests to evaluate changes during the 3-week treatment period between groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

A total sample of 16 participants was sufficient to reach a statistical power of 90 %. The calculation of the sample size was based on the results of a (non-placebo) controlled pilot project preceding the present study (Brunner et al., 2003). To determine the test-retest reliability of the measurements of blood lactate concentration and oxygen consumption at 150 watts before and after supplementation, intra-class correlation coefficients choosing a 2-way fixed model, excluding systematic error (ICC 3,1; Weir, 2005) were calculated. The analyses revealed ICC of 0.69 (PG) and 0.62 (AG), p < 0.05 considering oxygen consumption and ICC of 0.89 (PG) and 0.97 (AG), p < 0.01 considering lactate concentration.

Results

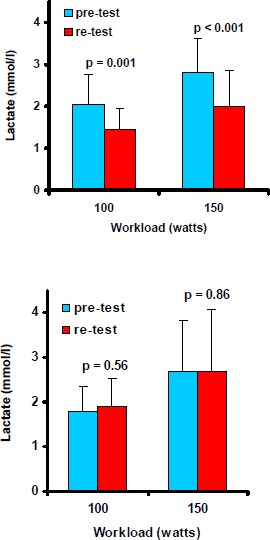

All subjects completed the 3-week regimen of L-arginine-L-aspartate or placebo without any side effects. Records of daily protocols of the participants showed that there were no substantial differences between groups in patterns of physical activity, nutrition or sleeping habits during the 3 weeks of study. Body mass did not change significantly between the groups (AG: 72.5 ± 6.5 vs. 71.8 ± 5.9 kg and PG: 75.5 ± 11.6 vs. 75.6 ± 11.4 kg). The L-arginine-L-aspartate intake effected a clearly lower blood lactate accumulation at 100 watts (2.0 ± 0.7 to 1.4 ± 0.5 mmol·l-1; p = 0.001) and 150 watts (2.8 ± 0.8 to 2.0 ± 0.9 mmol·l-1; p < 0.001) when compared to placebo (1.8 ± 0.6 to 1.9 ± 0.7 mmol·l-1; p = 0.6 and 2.7 ± 1.1 to 2.7 ± 1.4 mmol·l-1; p = 0.9) (p < 0.01 for different changes between groups) (Figure 1). Mean values of cardiovascular and respiratory responses to submaximal exercise in the pre-test and the re-test are shown in Table 2. Whereas steady state oxygen consumption at the end of each workload did not change between the groups, the total oxygen uptake over the 3-min period at 150 watts decreased after intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate from 6.32 ± 0.51 to 5.95 ± 0.40 l (p = 0.04) in comparison to placebo (6.07 ± 0.51 to 5.91 ± 0.50 l; p = 0.3) (p < 0.05 for different changes between groups). This was accompanied by a diminished minute ventilation at 100 and 150 watts (p < 0.05) and lower heart rates at 50, 100, and 150 watts (p < 0.05). Carbon dioxide output was decreased at 50 and 150 watts (p < 0.05) and the respiratory exchange ratio at 150 watts (p < 0.05) after the 3-week treatment period in the AG compared to the PG. The relatively high respiratory exchange ratios in both groups may be partly due to a slight hyperventilation because of the warm room conditions at both tests. The calculated rates of carbohydrate and fat oxidation from the respiratory analyses revealed an increased fat utilisation after L-arginine-L-aspartate supplementation (Table 3). Physical work capacity at the heart rate of 130 beats·min-1, calculated by intrapolation on the individual power-to-heart rate curves, was enhanced after L-arginine-L- aspartate (+10.4 ± 11.0 watts) versus placebo (- 9.9 ± 17.9 watts) (p < 0.02). Separate analyses did not indicate any differences between the occasionally smokers and non-smokers.

Figure 1.

Blood lactate concentration (mean values, SD) at 100 and 150 watts during the submaximal cycle ergometry before (pre-test) and after (re-test) 3 weeks of intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate (upper figure) or placebo (lower figure). P for changes between pre- and re-test.

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory responses to submaximal cycle ergometry before (pre-test) and after (re-test) 3 weeks of intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate or placebo. Data represent means (±SD).

| PLACEBO (n=8) | L-ARGININE-L-ASPARTATE (n=8) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 50 watts | 100 watts | 150 watts | Rest | 50 watts | 100 watts | 150 watts | ||

|

Heart Rate (bpm) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

80 (12) 82 (18) |

100 (9) 104 (9) |

117 (10) 121 (10) |

134 (10) 138 (10) |

77 (13) 80 (15) |

99 (8) 94 (6) * |

114 (8) 111 (8) * |

134 (8) 129 (7) ** |

|

Systolic

BP (mm Hg) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

128.8 (22.1) 118.6 (13.6) |

142.4 (16.5) 131.3 (14.5) |

151.8 (17.8) 147.4 (20.7) |

170.4 (20.2) 165.1 (14.4) |

133.8 (16.2) 122.4 (12.8) |

154.0 (13.9) 139.0 (14.4) |

161.6 (20.5) 148.6 (17.8) |

178.9 (22.5) 173.5 (17.2) |

|

Diastolic

BP (mm Hg) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

76.0 (8.6) 76.1 (12.7) |

70.0 (11.9) 68.4 (14.1) |

69.4 (14.2) 69.4 (13.2) |

70.3 (9.4) 66.7 (12.6) |

77.4 (18.2) 76.3 (10.1) |

72.3 (18.9) 71.3 (9.0) |

70.5 (13.2) 70.4 (12.3) |

70.0 (16.4) 71.6 (9.0) |

| RPP |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

10344 (2578) 9869 (2725) |

14123 (1689) 13720 (2122) |

17701 (2610) 17696 (2315) |

22848 (2973) 22719 (2313) |

10285 (1950) 9740 (1667) |

15163 (1401) 13057 (1556) |

18350 (2626) 16426 (2315) |

23908 (3646) 22533 (2847) |

| VE (l·min-1) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

15.5 (4.6) 14.6 (4.3) |

27.7 (5.5) 28.4 (4.3) |

38.5 (4.2) 39.6 (4.5) |

53.2 (6.4) 54.9 (5.5) |

14.9 (3.2) 15.6 (2.2) |

31.7 (4.8) 28.5 (3.6) |

39.4 (3.9) 37.6 (3.1) * |

53.3 (5.2) 50.7 (4.5) * |

| VO2 (l·min-1) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

.410 (.072) .375 (.090) |

1.082 (.118) 1.065 (.131) |

1.577 (.127) 1.551 (.123) |

2.105 (.188) 2.089 (.149) |

.429 (.094) .418 (.067) |

1.183 (.191) 1.100 (.136) |

1.651 (.105) 1.551 (.116) |

2.214 (.160) 2.071 (.139) |

| VCO2 (l·min-1) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

.380 (.090) .347 (.086) |

.952 (.134) .955 (.159) |

1.459 (.104) 1.482 (.134) |

2.105 (.161) 2.163 (.143) |

.397 (.102) .382 (.052) |

1.087 (.153) .926 (.097) * |

1.508 (.111) 1.403 (.132) |

2.199 (.140) 2.032 (.134)** |

| VE / VO2 |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

37.2 (5.8) 38.9 (4.5) |

25.6 (3.5) 26.7 (2.3) |

24.5 (2.5) 25.7 (3.5) |

25.3 (2.5) 26.4 (3.5) |

35.2 (6.2) 38.7 (11.3) |

27.1 (4.2) 26.3 (4.7) |

24.0 (3.2) 24.4 (2.8) |

24.2 (2.6) 24.6 (3.3) |

| VE / VCO2 |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

40.5 (4.6) 42.0 (4.0) |

29.1 (3.5) 29.9 (2.4) |

26.4 (2.6) 26.8 (2.3) |

25.3 (2.0) 25.4 (2.1) |

38.2 (6.1) 41.4 (7.3) |

29.3 (3.6) 31.1 (5.2) |

26.3 (3.6) 27.0 (3.0) |

24.3 (2.5) 25.1 (3.1) |

| RER |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

.92 (.10) .93 (.11) |

.88 (.04) .89 (.04) |

.93 (.04) .96 (.06) |

1.00 (.05) 1.04 (.07) |

.92 (.10) .93 (.16) |

.92 (.07) .85 (.08) |

.91 (.05) .90 (.05) |

.99 (.04) .98 (.05) * |

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01 for changes between groups. Abbreviations: BP = Blood pressure, VE = Minute ventilation, RPP = Rate pressure product, RER = Respiratory exchange ratio.

Table 3.

Rates of carbohydrate and fat oxidation from the respiratory analyses during submaximal cycle ergometry before (pre-test) and after (re-test) 3 weeks of intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate or placebo. Data represent means (SD).

| PLACEBO (n=8) | L-ARGININE-L-ASPARTATE (n=8) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 50 watts | 100 watts | 150 watts | Rest | 50 watts | 100 watts | 150 watts | ||

|

Caloric Equivalent

(kcal·l-1 O2) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

4.933 (.1014) 9.4936 (.096) |

4.899 (.057) 4.916 (.055) |

4.956 (.046) 4.980 (.037) |

5.025 (.028) 5.036 (.020) |

4.921 (.122) 4.907 (.105) |

4.950 (.082) 4.855 (.094) * |

4.942 (.067) 4.930 (.067) |

5.024 (.026) 5.011 (.039) |

|

TOTAL EnEx

(kcal·h-1) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

121.5 (22.6) 111.1 (26.6) |

318.1 (36.6) 314.4 (41.7) |

468.9 (36.0) 463.5 (36.6) |

634.6 (54.3) 631.1 (43.9) |

126.7 (29.1) 122.8 (18.3) |

351.0 (53.5) 320.0 (36.7) |

489.5 (29.8) 458.9 (34.6) |

667.3 (46.0) 622.5 (40.0) |

|

EnEx by CARBOH (kcal/h) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

86.7 (41.0) 77.7 (30.6) |

194.5 (62.0) 210.1 (73.5) |

355.1 (52.2) 379.4 (53.9) |

596.9 (42.1) 612.5 (41.5) |

91.7 (40.9) 74.1 (31.5) |

254.7 (70.6) 150.7 (11.0) * |

351.3 (89.2) 317.2 (88.2) |

622.8 (44.4) 561.4 (68.3)** |

|

EnEx by FAT (kcal·h-1) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

34.9 (27.8) 33.4 (26.9) |

123.6 (38.9) 104.2 (36.4) |

113.8 (60.4) 83.2 (45.9) |

37.7 (48.4) 18.6 (35.0) |

35.0 (23.3) 48.7 (38.6) |

96.3 (87.6) 169.3 (87.8) |

138.2 (89.6) 141.7 (80.8) |

44.4 (52.1) 61.1 (68.7) |

|

RELATIVE En Ex by CARBOH (%) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

69.1 (27.1) 70.4 (25.9) |

60.3 (15.1) 65.3 (15.0) |

76.1 (12.2) 81.9 (9.8) |

94.4 (7.2) 97.2 (5.3) |

70.5 (22.8) 62.4 (28.6) |

73.8 (22.0) 48.1 (25.7) * |

71.9 (18.0) 69.0 (18.1) |

93.6 (7.5) 90.3 (10.5) |

|

RELATIVE EnEx by Fat (%) |

Pre-Test Re-Test |

30.9 (27.1) 29.6 (25.9) |

39.7 (15.1) 34.7 (15.0) |

23.9 (12.2) 18.1 (9.8) |

5.6 (7.2) 2.8 (5.3) |

29.5 (22.8) 37.6 (28.6) |

26.2 (22.0) 51.9 (25.7) * |

28.1 (18.0) 31.0 (18.1) |

6.4 (7.5) 9.7 (10.5) |

* p<0.05;

§ p<0.01 for changes between groups. Abbreviations: EnEx = Energy Expenditure, CARBOH = Carbohydrates.

Discussion

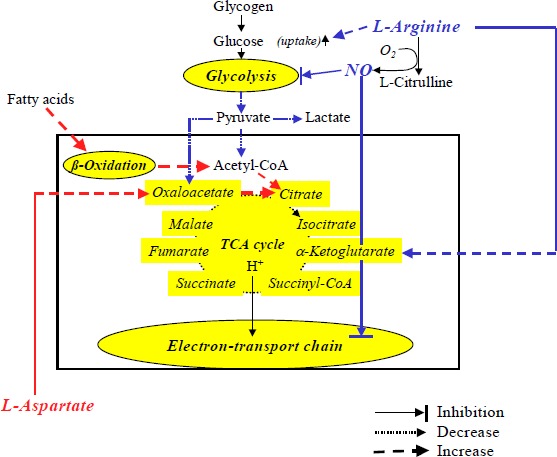

Three weeks of L-arginine-L-aspartate supplementation resulted in lower blood lactate concentrations and oxygen consumption, diminished glucose and enhanced fat oxidation, and reduced heart rate and ventilation during submaximal cycle exercise. The increase in submaximal physical work capacity and the right-shifted lactate-performance relationship indicate increased aerobic performance. Both L-arginine and L-aspartate may have contributed to the observed effects. Both of them might have acted as alternative substrates for glucose via aerobic metabolism and thus partly explain lower lactate concentrations and the lower respiratory exchange ratio observed after L- arginine-L-aspartate intake (see Figure 2). Although not measured, nitric oxide (NO), derived from L-arginine ingestion, may be speculated to be responsible for some of the presented results. NO may enhance glucose uptake and inhibit glycolysis (Balon and Nadler, 1994; Mohr et al., 1996). Thus, the NO-related inhibition of glycolysis could at least partly explain the lower lactate levels observed. Also Schaefer et al. (2002) recently demonstrated a clearly reduced exercise- induced increase in plasma lactate. They found a close relationship between changes in lactate levels and L-citrulline and suggested that the blunted lactate concentration was effected via the L- arginine-nitric oxide pathway. Others reported enhanced plasma lactate during exercise by NO synthase inhibition (Mills et al., 1999). NO also seems to regulate mitochondrial function through competitive inhibition of oxygen use in the electron transport chain, especially at cytochrome c oxidase (Kindig et al. 2001). It remains unclear whether this indicates a performance restriction or a more economical use of oxygen, e.g. at submaximal work, resulting in lower whole body oxygen consumption after L-arginine ingestion. Additionally, NO could exert its effect by acting directly on muscle fibres, “putting a brake ”on muscle contraction and its associated metabolism (Marechal and Gailly, 1999). Whereas L-arginine undoubtedly can increase exercise tolerance and performance in patients with cardiovascular diseases (Ceremuzynski, 1997; Craeger et al., 1992), no satisfactory clinical studies found any beneficial effects of L-arginine on endurance performance in healthy subjects or athletes. Therefore it may be assumed that L-aspartate made a noteworthy contribution to the beneficial effects observed in the present study. L-aspartate, a precursor of oxaloacetate, was suggested to improve biochemical capacity of muscle for oxidation of fatty acids through the Krebs cycle (Lancha et al., 1995). Actually the authors demonstrated that oxaloacetate precursors enhanced the muscle to utilize free fatty acids and to spare glycogen during endurance exercise, effecting clearly increased time to exhaustion. This would be in line with our observation of enhanced fat oxidation and improved aerobic performance after L-arginine-L- aspartate intake. Thus, when glycolysis is inhibited by L-arginine, L-aspartate may be an important source of oxaloacetate for the oxidation of FFA.

Figure 2.

Suspected pathways that may effect exercise metabolism with the combined supplementation of L-arginine and L-aspartate.

Besides, especially L-aspartate may increase the peripheral clearance of ammonia (Denis et al., 1991) with the consequence of delayed muscle fatigue and increased endurance performance. This effect, however, may be more important during high-intensity exercise (Edwards, 2003). Whereas several studies reported beneficial effects of L-aspartate on endurance performance (Ahlborg et al., 1968; Gupta and Scrivastava, 1973) others found not (Hagan et al., 1982; Maughan and Sadler, 1983). This inconsistency may be explained by the different test protocols applied, the different training states of athletes, different dosages of aspartate, etc. Taken together, L-aspartate seems to have at least equally ergogenic advantages in healthy athletes as L-arginine. The combined supplementation, however, might induce synergistic effects. L-arginine may primarily reduce lactic acid production by the inhibition of glycolysis and L-aspartate may favour fatty acid oxidation (Figure 2). The observed reduction of heart rates and ventilation at given submaximal workloads after L-arginine-L-aspartate may be consequences of diminished activities of chemoreceptors and metaboreceptors because of the reduced carbon dioxide production and blood lactate levels during exercise (Piepoli et al., 1995; Whipp and Wasserman, 1980).

Only a few studies evaluated the combined effects of a prolonged intake of L-arginine and L- aspartate. Beneficial effects on endurance performance have been reported, in uncontrolled studies, by Schmid et al. (1980) and Sellier (1979). In contrast, Colombani and colleagues (1999) recently reported no obvious metabolic benefits from the chronic supplementation with L-arginine-L-aspartate. However, they did not standardise exercise intensity and therefore their results cannot be used for comparisons. The present investigation demonstrated marked effects of prolonged L-arginine-L- aspartate intake on submaximal exercise of short duration. Further studies will have to evaluate its effects on more prolonged and/or intense exercise to exhaustion.

This is the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study investigating ergogenic effects of L- arginine and L-aspartate intake. However, it has several limitations. First of all the combined ingestion of these two amino acids hardly allows differentiation between effects of the single substances. On the other hand, mechanisms of action of each amino acid used in the present study have been investigated extensively, and based on available information, it is plausible to assume that jointly they exert synergistic effects. Another limitation may be the fact that the same dosage of the amino acid supplement was used for all participants, irrespective of their body mass. Although this may well enhance variability and thus cause a type II error it should have no influence on the significant effects we observed. In addition, an overestimation of carbohydrate oxidation rates may have occurred because of slight hyperventilation due to the warm room conditions. But as the room temperature was the same at the pre- and re-tests and for both groups, it too should not have influence on the relative changes observed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, prolonged nutritional supplementation with L-arginine-L-aspartate increases fat oxidation and reduces blood lactate levels and oxygen consumption and associated heart rate and ventilation during submaximal cycle exercise. This implies increased submaximal work capacity and exercise tolerance, which may have important implications for both athletes as well as patients.

Acknowledgments

We owe thanks to Mr. Reinhard Pühringer and Mr. Robert Treitinger for their technical and organisational support and to Dr. Rajam Csordas for editorial assistance and critical reading of the manuscript.

Biographies

Martin BURTSCHER

Employment:

Professor of Sport Science at the University of Innsbruck.

Degree:

MD, PhD.

Research interests:

Exercise physiology and pathophysiology; effects of high altitude.

E-mail: martin.burtscher@uibk.ac.at

Fritz BRUNNER

Employment:

Assistant Professor of Sport Science at the University of Innsbruck.

Degree:

PhD

Research interests:

Sports biomechanics.

E-mail: fritz.brunner@uibk.ac.at

Martin FAULHABER

Employment:

PhD student at the Dept. of Sport Science of the University of Innsbruck.

Degree:

MSc

Research interests:

Alpine sports, Exercise physiology.

E-mail: martin.faulhaber@uibk.ac.at

Barbara HOTTER

Employment:

Assistant Professor of Sport Science at the University of Innsbruck.

Degree:

PhD

Research interests:

Socio-psychology, Alpine sports.

E-mail: barbara.hotter@uibk.ac.at

Rudolf LIKAR

Employment:

Anaesthesiologist at the General Hospital of Klagenfurt.

Degree:

MD

Research interests:

Pain pathophysiology.

E-mail: r.likar@aon.at

References

- Ahlborg B., Ekelund L.G., Nilsson C.G. (1968) Effect of potassium-magnesium-aspartate on the capacity for prolonged exercise in man. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 74, 238-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balon T., Nadler J. (1994) Nitric oxide release is present from incubated skeletal muscle preparations. Journal of Applied Physiology, 77, 2519-2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks G.A. (1987) Amino acid and protein metabolism during exercise and recovery. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 19(Suppl. 5), 150-156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F., Hotter B., Burtscher M., Kornexl E. (2003) Effects of a prolonged intake of L-arginine-L-aspartate on motor performance. In: Abstract Book of the 8th Annual Congress of the European College of Sport Science. Salzburg 2003 455 [Google Scholar]

- Ceremuzynski L., Chamiec T., Herbacynska-Cedro K. (1997) Effect on supplemental oral L-arginine on exercise capacity in patients with stable angina pectoris. The American Journal of Cardiology 80, 331-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.W., Balwin S.N. (2001) L-arginine in the management of cardiovascular diseases. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 35, 755-764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombani P.C., Bitzi R., Frey-Rindova P., Frey W., Arnold M., Langhans W., Wenk C. (1999) Chronic arginine aspartate supplementation in runners reduces total plasma amino acid level at rest and during marathon run. European Journal of Nutrition 38, 263-270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creager M.A., Gallagher S.J., Girerd X.J., Coleman S.M., Dzau V.J., Cooke J.P. (1992) L-arginine improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypercholesterolemic humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 90, 1248-1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J.M. (1995) Carbohydrates, branched-chain amino acids, and endurance. The central fatigue hypothesis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition 5, 29-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis C., Dormois D., Linossier M.T., Eychenne J.L., Hanseux P., Lacour J.R. (1991) Effect of arginine aspartate on the exercise induced hyperammoniemia in humans: a two periods cross-over trial. Archives Internationales de Physiologie, de Biochimie et de Biophysique 99, 123-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards W.W. (2003) Arm crank power and hyperammonemia in response to l-aspartic acid supplementation. Dissertation. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College [Google Scholar]

- Gastmann U.A., Lehmann M.J. (1998) Overtraining and the BCAA hypothesis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 30, 1173-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremion G., Palud P., Gobelet C. (1989) Arginine aspartate and muscular activity. Part II. Schweizer Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin 37, 241-246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J., Srivastava K.K. (1973) Effect of potassium-magnesium aspartate on endurance work in man. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology 11, 392-394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan R.D., Upton S.J., Duncan J.J., Cummings J.M., Gettman L.R. (1982) Absence of effect of potassium-magnesium aspartate on physiologic responses to prolonged work in aerobically trained men. International Journal of Sports Medicine 3, 177-181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves M.H., Snow R. (2001) Amino acids and endurance exercise. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 11, 133-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig C.A., McDonough P., Erickson H.H., Poole D.C. (2001) Effect of L-NAME on oxygen uptake kinetics during heavy-intensity exercise in the horse. Journal of Applied Physiology 91, 891-896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider R.B. (1998) Central fatigue hypothesis and overtraining. : Overtraining in Sport. : Kreider R.B., Fry A.C., O´Toole M.Champaign, Illionis: Human Kinetics; 309-331 [Google Scholar]

- Kreider R.B., Miriel V., Bertun E. (1993) Amino acid supplementation and exercise performance: proposed ergogenic value. Sports Medicine 16, 190-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancha A.H., Recco M.B., Abdalla D.S., Curi R. (1995) Effect of aspartate, asparagine, and carnitine supplementation in the diet on metabolism of skeletal muscle during moderate exercise. Physiology and Behaviour 57, 367-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K.S., Grange R.W., Chang W.J., Kamm K.E., Sarelius I., Stull J.T. (1998) Skeletal muscle contractions stimulate cGMP formation and attenuate vascular smooth muscle myosin phosphorylation via nitric oxide. FEBS-Letters 431, 71-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marechal G., Gailly P. (1999) Effects of nitric oxide on the contraction of skeletal muscle. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 55, 1088-1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan R.J., Sadler D.J. (1983) The effects of oral administration of salts of aspartic acid on the metabolic response to prolonged exhausting exercise in man. International Journal of Sports Medicine 4, 119-123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A.J., Ho H.V., Le C.Q., Lin P.S., Bernstein D., Cooke J.P. (2001) L-arginine enhances aerobic exercise capacity in association with augmented nitric oxide production. Journal Applied Physiology, 90, 933-938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills P.C., Marlin D.J., Scott C.M., Smith N.C. (1999) Metabolic effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition during exercise in the horse. Research in Veterinary Science 66, 135-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr S., Stamler J.S., Brune B. (1996) Posttranslational modification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by S-nitrosylation and subsequent NADH attachment. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271, 4209-4214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepoli M., Clark A.L., Coats A.J. (1995) Muscle metaboreceptors in hemodynamic, autonomic, and ventilatory responses to exercise in men. American Journal of Physiology 269, H1428-1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid M.B. (1998) Role of nitric oxide in skeletal muscle: synthesis, distribution and functional importance. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 162, 401-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A., Piquard F., Geny B., Doutreleau S., Lampert E., Mettauer B., Lonsdorfer J. (2002) L-arginine reduces exercise-induced increase in plasma lactate and ammonia. International Journal of Sports Medicine 23, 403-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid P., Gleispach H., Wolf W., Pessendorfer H., Schwaberger P. (1980) Leistungs-beeinflussung und stoffwechselveränderungen während einer langzeitbelastung unter argininaspartat. Leistungssport 10, 486-495 [Google Scholar]

- Sellier J. (1979) Intéret de l´aspartate d´arginine sangenor chez des athletes de compétition en périod d´entrainement intensif. Revue de Medecine de Toulouse, 879 [Google Scholar]

- Weir J.P. (2005) Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 19, 231-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipp B.J., Wasserman K. (1980) Carotid bodies and ventilatory control dynamics in man. Federation Proceedings 39, 2668-2673 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]