Abstract

Recent studies in mammals have documented neural expression and mobility of retrotransposons and suggested that neural genomes are diverse mosaics. Here we report transposition in memory-relevant neurons in the Drosophila brain. Cell-type specific gene expression profiling revealed transposon expression is more abundant in mushroom body (MB) αβ neurons than in neighboring MB neurons. The PIWI-RNA (piRNA) proteins Aubergine and Argonaute 3, known to suppress transposons in the fly germline, are expressed in the brain and appear less abundant in αβ MB neurons. Loss of piRNA proteins correlates with elevated transposon expression in brain. Lastly, paired-end deep sequencing identified over 200 de novo transposon insertions in αβ neurons, including events into memory-relevant loci. Our observations indicate that genomic heterogeneity is a conserved feature of the brain.

Transposons comprise nearly 45% and 15-20% of the human and fly genome, respectively (1-3). Mobilized transposons can act as insertional mutagens and create lesions where they once resided (2). Recombination between homologous transposons can also delete intervening loci. Specific regions of the mammalian brain, most evidently the hippocampus, might be particularly predisposed to transposition (4, 5). LINE-1 (L1) retrotransposons mobilized during differentiation appear to insert in the open chromatin of neurally expressed genes (4-6). One such insertion in neural progenitor cells altered the expression of the receiving gene, and subsequent maturation of these cells into neurons (6). The mosaic nature of transposition could therefore provide additional neural diversity that might contribute towards behavioral individuality in addition to contributing towards neurological disorders (7-9).

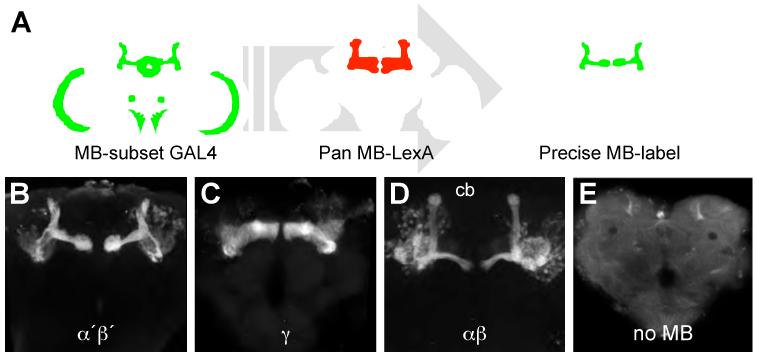

The Drosophila melanogaster mushroom bodies (MBs) are brain structures critical for olfactory memory. The approximately 2000 intrinsic MB neurons are divisible into α′β′, γ and αβ by morphology and roles in memory processing (10-13). In this study, we used cell-type specific gene expression profiling (14) to gain insight into cellular properties of MB neurons. Intersectional genetics (15) (Fig. 1A) allowed us to exclusively label MB α′β′, γ, and αβ neurons in the brain with green fluorescent protein, GFP (Fig. 1B-D). We also assayed for comparison a genotype where GFP labels most neurons in the brain, except MB neurons - the no MB group, (Fig. 1E). Sixty brains per genotype were dissected from the head capsule and dissociated by proteolysis and agitation before GFP-expressing single cell bodies were collected using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). Total RNA was isolated from 10000 cells per genotype and polyA RNA was amplified and hybridized to Affymetrix Drosophila 2.0 genome expression arrays. Each genotype was processed in four independent replicates (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1. Exclusive labeling of MB neuron subsets in the fly brain.

(A) MB-expressing GAL4s with expression elsewhere in the brain were intersected with an almost pan MB-expressing LexA. See Supporting Online Material for detail of genetic approach. Confocal projection of individual brains from flies labeling (B) α′β′ (C) γ and (D) αβ neurons. (E) all neurons in the brain, except MB neurons, no MB. Scale bar 40 μm.

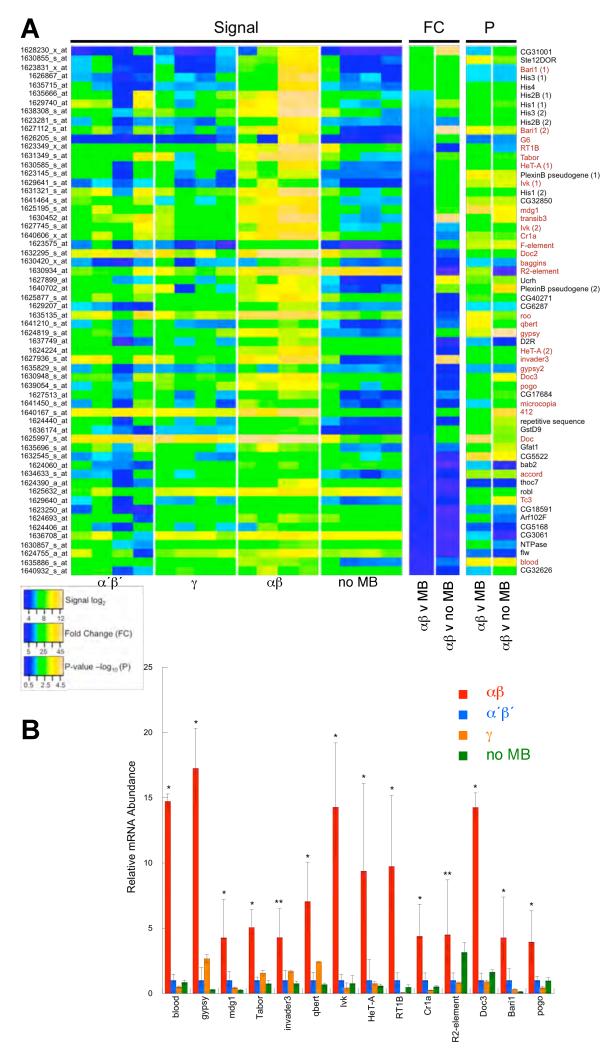

Fig. 2. Gene expression profiling MB neurons.

(A) Microarray data emphasizing elevated expression in αβ neurons. Each signal column per category represents an independent replicate. Fold change (FC) and t-test P values are shown for αβ versus other MB neurons (average value for α′β′ and γ) and αβ versus the no MB group. Transposons denoted in red. Scale bars linear for fold change, −log10 for P-value and log2 of the signal level. (B) QRT-PCR validation of increased transposon mRNA levels in αβ neurons. * denotes αβ signal significantly different to all other populations, all P≤0.05, T-Test. ** denotes αβ signal significantly different to MB but not no MB group for R2, and αβ significantly different to all except γ for invader3.

Routine statistical analysis for differentially expressed genes, including a multiple-testing correction across all sixteen datasets, did not reveal significant differences at a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05. We therefore used CARMAweb (16) to identify 146 mRNAs whose average signal was ≥7 in αβ neurons and that were also ≥2-fold higher than in α′β′. 29 of the top 60 transcripts from this list, that were significantly different from α′β′ signals by raw P-value, represent transposons (Fig. 2A and Table S1). Alignment of the corresponding values from the γ and no MB profiles showed a similarly significant bias in transposon expression over these samples. We identified retrotransposons that transpose via a replicative mechanism involving an RNA intermediate and DNA elements that use non-replicative excision and repair. Retrotransposons can be subdivided into long-terminal repeat (LTR) and Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements (LINEs). We found eleven LTR; Tabor, mdg1, roo, qbert, gypsy, invader3, gypsy2, microcopia, 412, accord and blood, twelve LINE-like; G6, Rt1b, HeT-A, Ivk, Cr1a, F element, Doc2, baggins, R2, Doc3 and Doc and four DNA elements; Bari1, pogo, Tc3 and transib3.

We further analyzed fourteen transposons, representing the most abundant in each class. Quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR) of RNA from independently purified cell samples confirmed transposon expression was significantly higher in αβ than other MB neurons (Fig. 2B). All transposons, other than R2, were also significantly higher in αβ than the rest of the brain. R2 is unique, because it exclusively inserts in the highly repeated 28S ribosomal RNA locus and heterochromatin (17).

Transposition is ordinarily regulated by chromatin structure and post-transcriptional degradation of transposon mRNA using complementary RNAs (18-25). The small interfering RNA (siRNA) pathway has been implicated in somatic cells (26). In contrast, the PIWI-associated RNA (piRNA) pathway has a more established role in the germline (19-21). The microarray analysis skewed our attention towards piRNA because the translocated Stellate locus, Stellate12D orphon (Ste12DOR) mRNA, was >20-fold higher in αβ than other MB neurons and the rest of the brain (Fig. 2A and Table S1). Stellate repeat transcripts are usually curtailed by piRNA, not siRNA (27, 28). Stellate repeats encode a Casein Kinase II regulatory subunit and piRNA mutant flies form Stellate protein crystals in testis (29). Immunostaining Stellate in the brain labeled puncta within αβ dendrites in the MB calyx, consistent with high Ste12DOR expression in wild-type αβ neurons (Fig. S1).

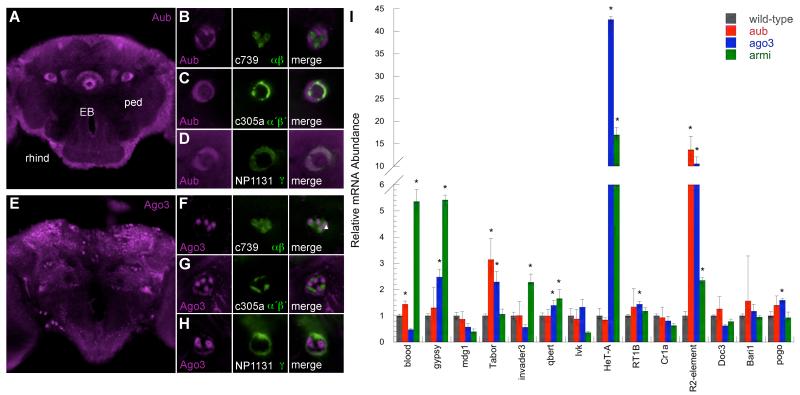

piRNAs are loaded into PIWI clade argonaute proteins Piwi, Aubergine (Aub) and Argonaute 3 (Ago3) (21). Piwi and Aub can amplify piRNA pools with Ago3 (30, 31). To investigate piRNA involvement in differential transposon expression we immunolocalized PIWI proteins and co-localized CD8::GFP to assign signals to MB neuron type (Fig. 3). Aub and Ago3 differentially labeled MB subdivision in addition to structures throughout the brain (Figs. 3, S2 and S3) but we did not detect Piwi (32). The ellipsoid body of the central complex, stained strongly for Aub but not at all for Ago3 (Figs. 3A, 3E, S2D and S3D) suggesting possible functional exclusivity of PIWI proteins in the brain.

Fig. 3. Aub and Ago3 are not abundant in αβ neurons.

(A) Aub immunostaining (magenta) labels the ellipsoid body (EB) and MB subdivision in the peduncle (ped). Single confocal section at the level of the MB peduncle. Dotted box denotes area in panels (B-D). (B) Aub labels α′β′ and γ neurons in the peduncle more than αβ. Aub staining is mutually exclusive to GFP (green) expressing αβ neurons but overlaps with (C) α′β′ and (D) γ neurons. (B-D) left panels Aub staining; middle GFP; right panel merge. (E) Ago3 immunostaining (magenta) labels neurons throughout the brain and MB subdivision in the peduncle. Single confocal section at the level of the MB peduncle. Dotted box denotes area in panels (F-H). (F) Ago3 staining is prominent in the αβ core (closed triangle) and does not overlap with outer GFP labeled αβ neurons (open triangle) nor (G) α′β′ but overlaps with (H) γ neurons. Left panels Ago3 staining; middle GFP; right panel merge. Scale bar 10μm. (I) Several transposon transcripts are elevated in ago3, aub and armi mutant fly brains. QRT-PCR analysis from wild-type, aubHN2/aubQC42, ago3t2/ago3t3 and armi1/armi27.1 mutant heads. Values normalized to wild-type heads. * denotes significant increase, P<0.05 (T-test).

Differential Aub and Ago3 label is most evident within axon bundles in the peduncle and lobes, where MB neuron types are anatomically discrete (Figs. 3A-H and S2). Aub protein co-localized with γ and α′β′ in the peduncle and lobes but was reduced in αβ in both locations (Figs. 3B-D and S2). Ago3 did not label MB lobes (Fig. S3) but co-localized with γ in the peduncle (Fig. 3H). Ago3 labeled core αβ (αβc) neurons but did not label outer αβ (Fig. 3F). Therefore outer αβ neurons do not abundantly express Aub or Ago3 suggesting transposon suppression is relaxed. In contrast, γ express Aub and Ago3, providing potential for piRNA amplification, and α′β′ express Aub. These patterns of Aub and Ago3 in the MB peduncle appear conserved in brains from D. erecta, D. sechellia and the more distantly related D. pseudoobscura species (Fig. S4).

Loss of siRNA function elevates transposon expression in the head (22). We replicated these findings using ago2414 and dcr-2L811fsX mutant flies (Fig. S5). In parallel we tested whether piRNA suppressed transposon expression using transheterozygous aub (aubHN2/aubQC42) and ago3 (ago3t2/ago3t3) (19, 33) and transheterozygous armitage (armi1/armi72.1) heads (34) (Fig. 3I). Levels of the 14 LTR, LINE-like and TIR group transposons verified to be expressed in αβ neurons (Fig. 2B) were assayed by QRT-PCR. 13 of the 14 transposons were significantly elevated in siRNA defective ago2 and dcr-2 mutants (Fig. S5). The piRNA defective aub, ago3 and armi mutants also exhibited significantly elevated levels of 9 of the 14 elements (Fig. 3I). LTR elements gypsy, Tabor and qbert, LINE-like HeT-A, RT1B and R2 and the TIR element pogo were higher in ago3 mutants. In addition blood, Tabor and R2 were elevated in aub flies and blood, gypsy, Tabor, invader3, qbert, HeT-A and R2 in armi mutants. Therefore, the piRNA pathway contributes to transposon silencing in the brain and low level Aub and Ago3 may permit expression in αβ neurons.

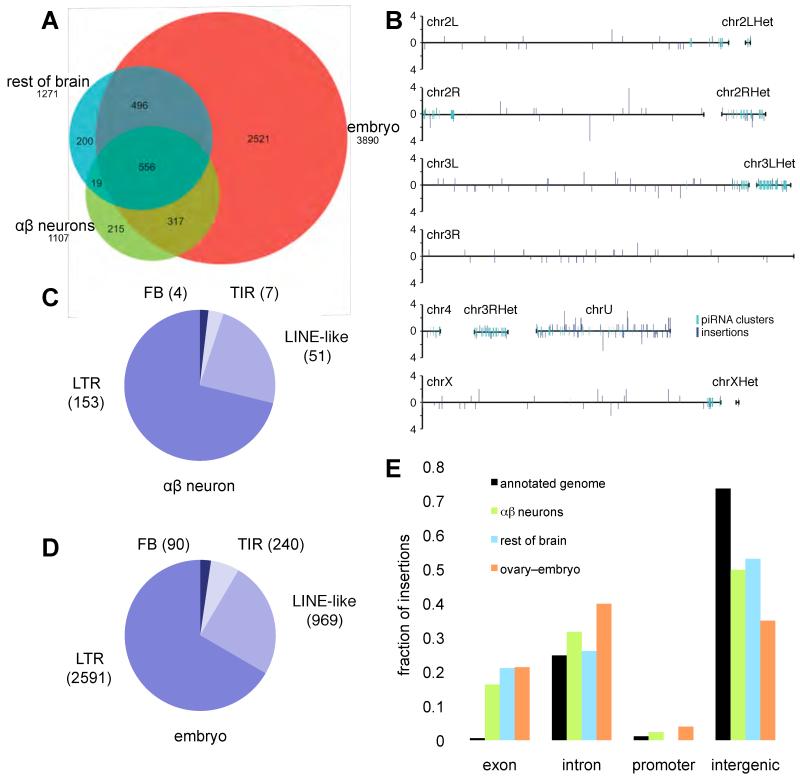

To determine whether transposons are mobile we mapped new insertions by deep sequencing (35) αβ DNA (Fig. 4). We purified αβ neurons by FACS, as for transcriptome analysis, but isolated genomic DNA. Insertions were defined by paired-end reads in which one end mapped to the annotated genome and the other to transposon sequence. To identify de novo transposition events in αβ neurons we compared the genomic position of transposons within αβ sequence to those located by sequencing DNA from genetically identical embryos. In addition we sequenced DNA from the remainder of the brain tissue from the FACS separation of αβ neurons (Fig. 4A and Table S4).

Fig. 4. Identification of de novo transposition events in αβ neurons.

(A) Venn diagram of transposon insertions identified in this study. Direct genome sequencing identified 215 insertion sites in αβ neuron DNA and 200 in DNA from other brain cells that were not present in embryo DNA from genetically identical sibling flies. (B) Chromosomal distribution of new transposon insertions in αβ neurons. Bar height indicates number of insertions in each location. piRNA clusters are shown. (C) The proportion of new insertions found for each transposon class in αβ neurons. (D) Proportion of insertions per transposon class in the inherited fly genome from our sequencing of embryo DNA. (E) Distribution of transposons in the annotated genome significantly differs from de novo insertions in αβ neurons, the rest of brain and ovary DNA with respect to neighboring genes (p-value <2.2E-16 for αβ neurons, the rest of brain and ovary; χ2 test).

These studies identified 3890 transposon insertions in embryo DNA that differed from the published Drosophila genome sequence (Fig. 4A). In comparison αβ neuron DNA revealed 215 additional sites. The remaining brain tissue uncovered 200 new insertions, including 19 identical to those in αβ neurons. The αβ and other brain insertions are likely de novo because the sequencing depth was ten times higher for embryos (34.1 fold) than neurons (3.1 fold), due to the ease of collecting material. By randomly sampling reads to yield 1-fold genome coverage, we calculated 129 new transposon insertions per αβ neuron genome (Table S2). Sequencing single neurons (36) would reveal the exact cellular frequency and heterogeneity of transposition events.

New αβ insertions occurred across all chromosomes without obvious regional bias (Fig. 4B). In addition, insertions resulted from 49 different transposons representing LTR, LINE-like, TIR and Foldback (FB) classes (Fig. 4C). They included 11 of the 27 transposons in the αβ transcriptome (Fig. 2A) and the number of insertions per class is consistent with their prevalence in the genome (Fig. 4D). Therefore, many transposons mobilize in αβ neurons.

108 of the 215 de novo αβ insertions mapped close to identified genes (Fig. 4E and S6). Of these, 35 disrupted exons, 68 introns and 5 fell in promoter regions (<1kb from transcription start site). The remaining 107 insertions located to piRNA clusters or intergenic regions and were not assigned to a particular gene. A similar distribution was observed for the 200 new insertions in the rest of the brain (Fig. 4E and S6). The reference fly genome has 258, 11110, 502 and 33008 transposon insertions in exonic, intronic, promoter and intergenic regions respectively. Therefore both groups of brain cells had a significantly larger fraction of de novo insertions within exons and fewer in intergenic regions than transposons annotated in the genome (Fig. 4E and Table S8). To test whether such a distribution was unique to neurons we analyzed de novo insertions in ovary, again using embryo sequence as the comparison. New insertions in ovary DNA revealed a similar skew towards exons (Fig. 4E and Table S8).

In mammals, active L1 elements appear to disrupt neurally expressed genes (4-6). New αβ neuron insertions, but not those in other tissue (Tables S7 and S9), were significantly enriched in 12 Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Benjamini FDR <5%; Tables S4 and S5) all of which are related to neural functions. Moreover, promoter regions from 18 of 20 of the targeted genes drive expression in αβ neurons (Table S10). We found exonic insertions in gilgamesh, derailed and mushroom body defect and intronic insertions in dunce and rutabaga (Table S3), all of which have established roles in MB development and function (37-40). In addition, MB neurons are principally driven by cholinergic olfactory projection neurons (41) and receive broad GABA-ergic inhibition (42) and dopaminergic modulation through G-protein coupled receptors (43). We identified intronic insertions in nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α 80B, G protein-couple receptor kinase 1 and cyclic nucleotide gated channel-like and an exonic insertion in GABA-B-receptor subtype 1 (Table S3). Transposon-induced mosaicism could therefore alter integrative and plastic properties of individual MB αβ neurons.

In conclusion, our data establish that transposon-mediated genomic heterogeneity is a feature of the fly brain and possibly other tissues. Taken with prior work in rodents and humans (4-6), it suggests genetic mosaicism may be a conserved characteristic of certain neurons. Work in mammals indicates L1 expression occurs because the L1-promoter is released during neurogenesis (6, 21). Our data are consistent with such a model and also that transposons avoid post-transcriptional piRNA silencing in adult αβ neurons.

A recent study described a role for piRNA in epigenetic control of memory-related gene expression in Aplysia neurons (44). It is therefore possible that MB neurons differentially utilize piRNA to control memory-relevant gene expression, and transposon mobilization is an associated cost. Since we found transposon expression in αβ neurons of adult flies, it is conceivable that disruptive insertions accumulate throughout life leading to neural decline and cognitive dysfunction.

Alternatively, permitting transposition may confer unique properties across the 1000 neurons in the αβ ensemble and potentially produce behavioral variability between individual flies in the population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Data are available through ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) and NCBI Short Read (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/sra) archives as E-MEXP-3798 and SRP017718. We thank Anand Vodala, Jerome Menet, Kate Abruzzi and Noreen Francis for advice with techniques. S.W. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Basic Biomedical Sciences, The Gatsby Charitable Foundation, Oxford Martin School and grants MH069883 and MH081982 from NIH. M.R. is funded by NS044232 and NS045713 from NIH and the Ellison Medical Foundation. Z.W. and W.T. are funded by R01HD049116 from NIH.

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

References and Notes

- 1.Cordaux R, Batzer MA. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:691. doi: 10.1038/nrg2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazazian HHJ. Science. 2004;303:1626. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaminker JS, et al. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0081. RESEARCH0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coufal NG, et al. Nature. 2009;460:1127. doi: 10.1038/nature08248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillie JK, et al. Nature. 2011;479:534. doi: 10.1038/nature10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muotri AR, et al. Nature. 2005;435:903. doi: 10.1038/nature03663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muotri AR, Gage FH. Nature. 2006;441:1087. doi: 10.1038/nature04959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer T, McConnell MJ, Marchetto MC, Coufal NG, Gage FH. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:345. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gage FH, Muotri AR. Sci Am. 2012;306:26. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0312-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum AL, Li W, Cressy M, Dubnau J. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trannoy S, Redt-Clouet C, Dura JM, Preat T. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1647. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krashes MJ, Keene AC, Leung B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. Neuron. 2007;53:103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu D, Akalal DB, Davis RL. Neuron. 2006;52:845. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagoshi E, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:60. doi: 10.1038/nn.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shang Y, Griffith LC, Rosbash M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809577105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainer J, Sanchez-Cabo F, Stocker G, Sturn A, Trajanoski Z. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakubczak JL, Burke WD, Eickbush TH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muotri AR, et al. Nature. 2010;468:443. doi: 10.1038/nature09544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, et al. Cell. 2009;137:509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vagin VV, et al. Science. 2006;313:320. doi: 10.1126/science.1129333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:246. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghildiyal M, et al. Science. 2008;320:1077. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito K, Siomi MC. Dev Cell. 2010;19:687. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennecke J, et al. Science. 2008;322:1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1165171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang N, Kazazian HHJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:763. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:94. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aravin AA, et al. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1017. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravin AA, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6742-6750.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bozzetti MP, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennecke J, et al. Cell. 2007;128:1089. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunawardane LS, et al. Science. 2007;315:1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1140494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox DN, et al. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3715. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schupbach T, Wieschaus E. Genetics. 1991;129:1119. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.4.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomari Y, et al. Cell. 2004;116:831. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khurana JS, et al. Cell. 2011;147:1551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evrony GD, et al. Cell. 2012;151:483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomchik SM, Davis RL. Neuron. 2009;64:510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan Y, Yu D, Pletting J, Davis RL. Neuron. 2010;67:810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreau-Fauvarque C, Taillebourg E, Boissoneau E, Mesnard J, Dura JM. Mech Dev. 1998;78:47. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hovhanyan A, Raabe T. J Neurogenet. 2009;23:42. doi: 10.1080/01677060802471700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasuyama K, Meinertzhagen IA, Schurmann FW. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:211. doi: 10.1002/cne.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Davis RL. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:53. doi: 10.1038/nn.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waddell S. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:457. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajasethupathy P, et al. Cell. 2012;149:693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.