Abstract

Alterations in the overall cerebral hemodynamics have been reported in multiple sclerosis (MS); however, their cause and significance is unknown. While potential venous causes have been examined, arterial causes have not. In this study, a multiple delay time arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging sequence at 3T was used to quantify the arterial hemodynamic parameter bolus arrival time (BAT) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) in normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and deep gray matter in 33 controls and 35 patients with relapsing–remitting MS. Bolus arrival time was prolonged in MS in NAWM (1.0±0.2 versus 0.9±0.2 seconds, P=0.031) and deep gray matter (0.90±0.18 versus 0.80±0.14 seconds, P=0.001) and CBF was increased in NAWM (14±4 versus 10±2 mL/100 g/min, P=0.001). Prolonged BAT in NAWM (P=0.042) and deep gray matter (P=0.01) were associated with higher expanded disability status score. This study demonstrates alteration in cerebral arterial hemodynamics in MS. One possible cause may be widespread inflammation. Bolus arrival time was longer in patients with greater disability independent of atrophy and T2 lesion load, suggesting alterations in cerebral arterial hemodynamics may be a marker of clinically relevant pathology.

Keywords: hemodynamics, inflammation, magnetic resonance imaging, multiple sclerosis, perfusion imaging, relapsing–remitting

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disabling disease of the central nervous system, characterized by the presence of focal white matter lesions, which exhibit inflammation, demyelination, and axonal loss.1 While inflammation within the lesions is the most visible aspect of the neuropathology of MS, it is increasingly recognized that a more widespread and subtle form of inflammation also occurs within the normal-appearing white and gray matter, characterized pathologically by infiltration of lymphocytes, perivascular inflammation, and clusters of activated microglia.1, 2 These widespread inflammatory changes may have clinical relevance, as they correlate with markers of neuroaxonal damage and loss,3, 4 which in turn is associated with the accrual of fixed disability.1, 3

Ongoing inflammatory processes in normal-appearing white and gray matter have been challenging to study using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as they are not associated with a frank breach of the blood–brain barrier that can be detected as a region of gadolinium contrast enhancement.5 However, inflammation can cause more subtle microscopic alteration in vascular function,6 and lead to increases in vasodilatory nitric oxide7 and glutamate.8 Using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, an increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) has also been observed in prelesional normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) for several weeks before the development of a focal white matter lesion,9 and significant increase in cerebral blood volume is seen at the earliest stages of both new lesion development10 and existing lesion reactivation11, 12 in animal models of MS. These increases in CBF and cerebral blood volume are the earliest MRI detectable changes in lesions, and precede changes in blood–brain barrier permeability, T2 relaxation, and alteration in diffusion. It is possible that CBF and cerebral blood volume changes are sensitive to inflammation during an early stage of lesion development, which may be a critical step in lesion genesis, and MRI measures sensitive to these subtle vascular changes within the normal-appearing white and gray matter could determine the extent of this inflammation. As inflammation may both promote the development of focal demyelinating lesions, and contribute to axonal loss, measures sensitive to this inflammation could also help elucidate its pathologic significance in vivo.

As inflammation and release of vasoactive substrates could cause widespread arteriolar dilatation leading both to increased CBF and decreased arterial flow velocity due to increase in arterial cross-sectional area,13 joint measurement of CBF and cerebral arterial hemodynamics may be a promising approach to assess inflammation using MRI. Previous studies in MS have shown alteration in overall cerebral hemodynamics, with studies demonstrating significant prolongation in cerebral circulation time,14 the minimum time taken for blood to travel from carotid artery to jugular vein, and increase in mean transit time,15, 16, 17 a measure of the average time taken for blood to traverse from the arterial to venous circulation. These overall cerebral hemodynamic changes could not be explained by venous abnormalities;14, 17 however, cerebral arterial hemodynamic parameters were not specifically studied.

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is an MRI method that allows non-invasive measurement of CBF, using inversion of arterial water spins as a tracer. When multiple delay times after arterial labeling are sampled, the cerebral arterial hemodynamic measure bolus arrival time (BAT) can be measured, defined here and previously18 as the time from labeling of blood in feeding arteries to its first arrival in the capillary network of the voxel of interest. Bolus arrival time is synonymous with the term arterial transit time, which has also been used in some previous studies.19, 20, 21, 22 Arterial spin labeling is particularly well suited to quantifying BAT when compared with contrast-based MRI methods because of the higher temporal resolution possible, and the fact that labeling can occur much closer to the tissue of interest, reducing temporal dispersion of the bolus. Bolus arrival time provides complementary information to CBF, and is distinct from mean transit time and time to peak, which are typically measured in PET and contrast-based MRI and CT techniques.23 In particular, the time to peak measurements always include both a BAT component and an MTT component, rendering a direct comparison inappropriate. Knowledge of BAT also enables more accurate quantification of perfusion, particularly where BAT is prolonged by pathology.23 A previous ASL study revealed increase in CBF in white matter and decrease in gray matter in patients with MS,24 but could not quantify BAT, as only a single delay time point was used.

The purpose of this study was to quantify BAT and CBF in patients with relapsing–remitting MS and controls using a multiple delay time ASL MRI sequence, to determine whether cerebral arterial hemodynamics are altered in MS, and if they are associated with clinical disability. We investigated patients with relapsing–remitting MS, as a greater knowledge of cerebral arterial hemodynamics may provide insight into the pathophysiological processes occurring during an earlier and more inflammatory stage of the disease.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

All procedures on human subjects were performed as described in a protocol approved by the Central London Research Ethics Committee 4 and performed as per Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Patients with MS were recruited from MS clinics in the hospital, and controls were recruited from a database of volunteers interested in research. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of clinically definite relapsing–remitting MS,25 or no neurologic disease in the healthy controls, and age between 18 and 65. Exclusion criteria were presence of other neurologic conditions, presence of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, or contraindication to MRI, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Patients with MS were at least 3 months from their last clinical relapse and last treatment with steroids. All subjects had a medical and neurologic history and examination on the day of their MRI scan, and patients with MS were assessed using the expanded disability status scale (EDSS).26 Thirty-five patients with MS and 33 controls were scanned (Table 1). Of the patients with MS, 12 were taking interferon beta-1a preparations, 4 interferon beta-1b preparations, and 6 glatiramer acetate. Thirteen took no disease-modifying treatment. All controls had normal appearances of T1-and T2-weighted MRI scans of the brain. Scans took place between September 2010 and September 2012.

Table 1. Summary of patient and control characteristics.

| Subject type | Age | Gender M:F | Median EDSS (range) | Disease duration in years | Brain parenchymal fraction | T2 lesion volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | 38.1±8.0 | 12:23 | 2.5 (0–6.5) | 8.2±6.5 | 75.1±1.8% | 9.5 (±11.6) mls |

| Controls | 40.0±11.1 | 14:19 | NA | NA | 76.2±1.4%a | NA |

EDSS, expanded disability status score; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Unless otherwise stated results are mean± s.d.

difference from controls P<0.01.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Acquisition

A 3.0 Tesla MRI scanner with 32-channel receive coil was used (Phillips Healthcare Systems, Best, The Netherlands). The center section was orientated along the subcallosal line.

Cerebral blood flow and bolus arrival time were assessed using the QUASAR MRI sequence, a multiple delay time, pulsed ASL sequence.19, 21 Noteworthy features of the sequence are that it employs a series of arterial crusher gradients in four diagonal directions (+x,+y,+z);(−x,+y,+z);(+x,−y,+z);(−x,−y,+z) to remove signal from arterial blood traveling at greater than 3 cm/second. This prevents overestimation of CBF and underestimation of BAT in tissue containing or close to transiting arteries and arterioles. The sequence also uses ‘Look-Locker' sampling to capture a train of images at 13 delay times after arterial labeling. These serial temporal measurements, in combination with the vascular crusher gradients, enable determination of the exact moment that the labeled arterial bolus first enters the capillary vasculature in the voxel of interest. The time from ASL to this point is defined here, as previously, as the BAT.18 Other scan parameters were: TR 4,000 milliseconds, TE 23 milliseconds, 13 delay times (40 to 3,640 milliseconds), ΔT1 300 milliseconds, field of view 240 × 240, voxel size 3.75 × 3.75 × 6 mm3, seven axial slices, slice gap 2 mm, flip angle=35/11.7°, SENSE=2.5, 84 averages (48 with vascular crusher gradients of 4 cm/second, 24 with no vascular crusher gradients, 12 with low flip angle), scan time 6 minutes 7 seconds. To minimize the effect of any change in physiologic parameters occurring during the course of the scanning session, the ASL was performed as the first sequence.

Two further sequences were acquired to assist region of interest (ROI) positioning on the ASL R1 map, and to quantify brain volume and lesion load. (i) A three-dimensional T1-weighted turbo gradient echo sequence with parameters: TR 6.9 milliseconds, TE 3.1 milliseconds,TI 824 milliseconds, field of view 256 × 256 × 180 mm3, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, 180 sagittal slices, scan time 6 minutes 31 seconds. This scan was used for brain parenchymal fraction (BPF) assessment. (ii) A fast spin multi echo scan with parameters: TR 5,230 milliseconds, TE1 16 milliseconds, ΔTE 16 milliseconds, 7 echoes, field of view 240 × 180 × 152 mm3, voxel size 1x1 × 2 mm3, 76 axial slices, acquisition time 6 minutes 48 seconds. The 4th echo with TE of 64 milliseconds was used for lesion detection as a T2-weighted scan.

Arterial Spin Labeling Post Processing

Post processing of the ASL sequence was performed as previously described19, 21 using a Windows 7 PC (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) running IDL 6.1 (ITT Visual Information Solutions, Boulder, CO, USA) to produce maps of BAT, CBF, and tissue R1. In short, pairs of images showing strong motion artefacts were automatically discarded. Labeled images were subtracted from non-labeled images to produce ΔM images. Arterial blood volume was calculated from the signal arising from fast moving arterial blood by subtraction of ΔM with vascular crusher gradients on from ΔM with vascular crusher gradients off. From these arterial blood volume maps, voxels containing arterial input functions were automatically identified, defined as having greater than 1.2% arterial blood volume. Bolus arrival time was calculated from the time difference between arterial labeling and the first arrival of the labeled blood at the capillaries, assessed from the ΔM maps with vascular crusher gradients on. ΔM with vascular crusher gradients on was additionally deconvoluted and scaled by the arterial input function to quantify CBF.

This MRI sequence and post processing method has been studied in a worldwide multi center test–retest study of 284 healthy controls. A mean gray matter CBF of 47.4 mL/100 g per minute with a within subject standard deviation of 4.7 mL/100 g per minute, and a mean gray matter BAT of 0.82 seconds with within subject standard deviation of 0.05 seconds was reported.21

Region of Interest Placement

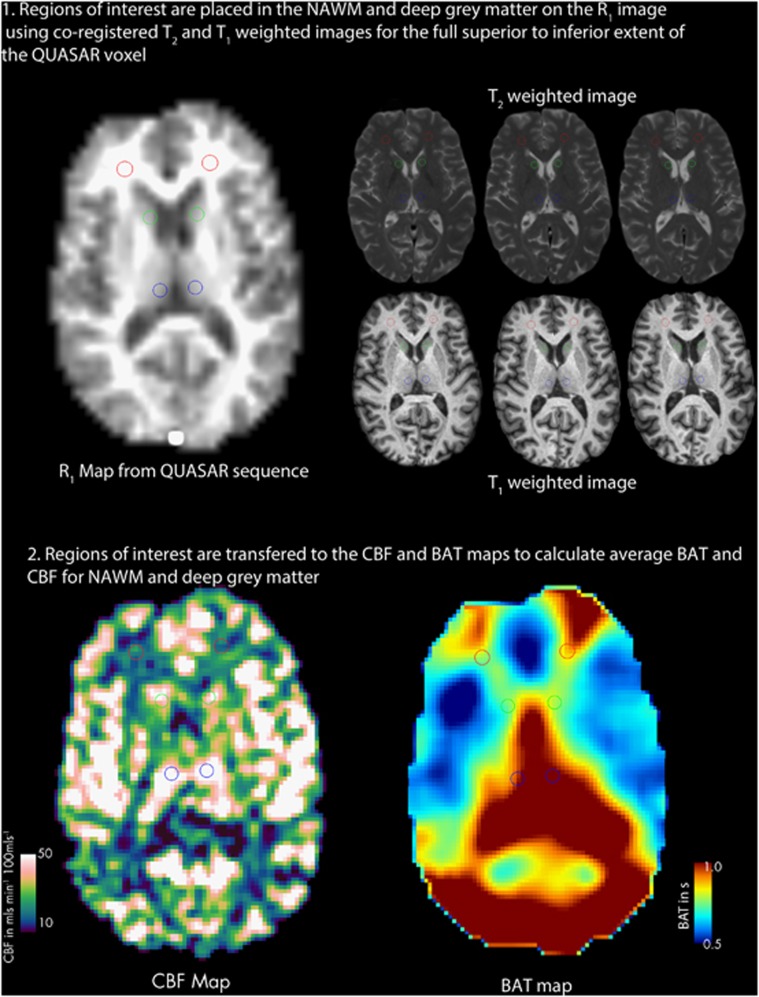

T1-weighted and T2-weighted images were registered to the R1 map calculated from the QUASAR sequence using an affine transformation with the NiftyReg toolkit (University College London, UK; www.sourceforge.net/projects/niftyreg).27, 28 Regions of interest were then placed onto the original R1 map from the ASL sequence using the T1-and T2-weighted images registered to the R1 map as a guide (Figure 1). Regions of interest were placed to avoid lesions and blood vessels, and placed in regions of the white matter away from known vascular border zones. Fourteen ROI, 4 to 6 voxels in volume (337.5 to 506.25 mm3) were placed in the NAWM of the frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes, four ROI, four voxels in volume (337.5 mm3) were placed in the thalamus and two ROI of four voxels (337.5 mm3) were placed in the caudate using JIM 6.0 (Xinapse systems, Northants, UK; http://www.xinapse.com). Regions of interest were combined and applied to the CBF and BAT maps to calculate a single mean CBF and BAT for NAWM and deep gray matter for each subject.

Figure 1.

Region of interest (ROI) placement. Regions of interest were placed on the R1 map from the arterial spin labeling (ASL) sequence using co-registered T1-weighted and T2-weighted scans. The image shows two of the 14 ROI placed in the white matter (red), and four of the six regions of interest placed in caudate (green) and thalamus (blue) Key: NAWM, normal-appearing white matter; CBF, cerebral blood flow; BAT, bolus arrival time.

Group-Averaged Maps

Group-averaged maps were made for the purpose of illustrating the results. The inverse of the matrix from the registration of the T1-weighted image to the ASL R1 map was multiplied by the matrix obtained from the affine registration of the T1-weighted image to the Montreal Neurological Institute template using the NiftiReg toolkit. This derived matrix was used to transform all the CBF and BAT maps to Montreal Neurological Institute space to enable group averages to be produced. As registration errors can occur, and these errors may be increased where brains with pathology are registered to a template created from healthy volunteers,29 these group-averaged maps were used for illustration only, and not used to quantify CBF and BAT.

Brain and Lesion Volume Measurement

Using the three-dimensional T1-weighted scan, all white matter lesions were outlined using the region of interest toolkit of JIM 6.0, and were filled with simulated NAWM signal intensities to improve the accuracy of segmentation. Neck slices were removed, and images were segmented into white, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid volume fraction maps using the FAST algorithm version 4.1 of FSL 4.1.3. Gray, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid volumes were calculated using the partial volume estimation method (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FAST#Tissue_Volume_Quantification). Brain parenchyml fraction was calculated by adding white and gray matter volumes together and dividing by total intracranial volume.

Lesions were identified using the 4th echo of the two-dimensional multi echo spin echo sequence, corresponding to a T2-weighted image with TE of 64 milliseconds. Lesions were outlined by a single operator, using a semi-automated technique based upon local thresholding using the region of interest toolkit of JIM 6.0. Lesion volume was calculated by multiplying lesion area by slice thickness.

Statistical Analysis

The majority of the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21 (IBM, New York, USA) and linear regression and subsequent bootstrapping analysis was performed using Stata 12.1 (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA).

Paired t-test was used for intrasubject comparison of regional CBF and BAT values in controls. Cerebral blood flow and BAT were compared between patients and controls using multiple linear regressions with CBF or BAT, the dependent variable and age and gender entered as co-variates. The analyses were repeated with BPF as an additional co-variate to assess whether differences seen were statistically independent of brain atrophy. Linear regression was also used to compare CBF and BAT between patients who took disease-modifying drugs compared with those who did not, with co-variates of age and disease duration.

In patients with MS, multiple linear regression was used to investigate associations between EDSS and CBF or BAT, with EDSS the dependent variable, CBF or BAT predictors, and gender and disease duration co-variates. Regression was repeated with T2 lesion volume and BPF as additional co-variates to determine whether associations seen were statistically independent of lesion volume and atrophy. As EDSS is not normally distributed, confidence intervals and P-values obtained were confirmed using non-parametric bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap estimates with 1,000 replicates. This allowed association with EDSS to be adjusted for confounders in a standard regression context.

Linear regression was used to assess the association of BAT and CBF with BPF and T2 lesion volume, with co-variates of age and disease duration, and to assess the relationship between BAT and CBF in patients and controls.

Results are presented as mean±s.d. Statistical significance is reported at P⩽0.05. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, as we were investigating a number of different, a priori hypotheses, and in such contexts, correction can be inappropriate. Nevertheless, P-values close to 0.05 should always be interpreted sensibly with caution.

Results

Results in Controls

As BAT is a measure of the time taken for transit of the bolus to the tissue of interest, it is related to the anatomy of the feeding vasculature, rather than of the tissue itself. For this reason, a distinct pattern of BAT was seen, with prolongation seen at the border zone territories of the major intracranial arteries (i.e. between the middle and posterior or anterior cerebral artery) (Figures 1 and 2A). This pattern has been previously reported in other studies using the same ASL technique.21, 30

Figure 2.

Group-averaged maps of bolus arrival time (BAT) in controls (A) and patients with multiple sclerosis (B) registered to Montreal Neurological Institute space at three different levels (template shown for reference in panel C. Note that prolongations of BAT are seen in the border zone territories between the anterior and middle cerebral artery territories (at 1 o'clock and 11 o'clock with respect to the map) and the middle and posterior cerebral artery territories (at 4 o'clock and 8 o'clock with respect to the map). Global increase in BAT is seen in patients with multiple sclerosis (B) as compared with controls (A).

Bolus arrival time was shorter in the deep gray matter as compared with the white matter (0.80 seconds±0.14 versus 0.92±0.15 seconds, P=0.001) (Figure 2A) and CBF was higher in deep gray matter as compared with white matter in healthy controls (46.0±5.7 versus 10.1±2.1 mL/100 g/min, P<0.001) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Group-averaged maps of cerebral blood flow (CBF) in controls (A) and patients with multiple sclerosis (B) registered to Montreal Neurological Institute space at three different levels (template shown for reference in panel C. A reduction in CBF can be seen in deep gray matter in patients with multiple sclerosis (B) when compared with controls (A). The increase in white matter CBF in patients with multiple sclerosis is harder to see because of the windowing chosen.

In controls, BAT in the deep gray matter was longer with increasing age (coefficient=0.0059, P=0.004) (i.e. BAT increases by 5.9 milliseconds per year), and was significantly longer in men as compared with women (mean difference=+0.093 seconds, P=0.032). No significant association was seen between age or gender and BAT or CBF in white matter, and no significant association was seen been between age or gender and CBF in deep gray matter.

Bolus Arrival Time and Cerebral Blood Flow in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Differences between patients with MS and controls were initially assessed with co-variates of age and gender. In these analyses, BAT was significantly longer in NAWM (1.00±0.20 versus 0.92±0.15 seconds, P=0.017) (Figure 2B) and in deep gray matter (0.90±0.18 versus 0.80±0.14 seconds, P=0.001) in patients with MS compared with controls. Cerebral blood flow was also increased in NAWM (14.4±4.4 versus 10.1±2.1 mL/100 g per min, P<0.001), but was decreased in the deep gray matter (40.3±12.0 versus 46.0±5.7 mL/100 g/min, P=0.005) (Figure 3B) in patients with MS compared with controls.

When BPF was added as an additional co-variate to the analysis, the increases seen in BAT in NAWM and deep gray matter were still statistically significant (P=0.031 and P=0.01, respectively), as was the increase in CBF in NAWM (P=0.001) (Table 2 and Figures 4A and 4C) indicating that these differences are statistically independent of changes in BPF. However, the decrease in deep gray matter CBF was no longer significant (P=0.81) (Figure 4D). Bolus arrival time and CBF in NAWM and deep gray matter were not significantly different between patients who took disease-modifying drugs compared with those who did not.

Table 2. Mean CBF and BAT results in patients and controls.

| Control | MS | P differencea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAT in seconds | |||

| NAWM | 0.92±0.15 | 1.0±0.20 | 0.031 |

| Deep gray matter | 0.80±0.14 | 0.90±0.18 | 0.01 |

| CBF in mL/100 g per minute | |||

| NAWM | 10.1±2.1 | 14.4±4.4 | 0.001 |

| Deep gray matter | 46.0±5.7 | 40.3±12.0 | 0.81 |

BAT, bolus arrival time; CBF, cerebral blood flow; MS, multiple sclerosis; NAWM, normal-appearing white matter.

Results shown are mean±s.d.

Significance assessed using regression with co-variates of age, gender, and brain parenchymal fraction.Bold values are significant at P<0.05.

Figure 4.

Box plot of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and bolus arrival time (BAT) in deep gray matter and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) in controls and patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Differences are assessed using linear regression with co-variates of gender, disease duration, and brain parenchymal fraction (BPF). In NAWM, significant increase in CBF (A) with prolongation of BAT (B) is seen in patients with MS (first row). In deep gray matter, decrease in CBF is not significantly different once BPF is added as a co-variate (C) but BAT is significantly prolonged (D) in patients with MS (second row).

Averaged plots of ΔM in patients and controls are shown in Figure 5 as an additional method of visualizing this data, showing delayed initial increase and lower peak of ΔM in deep gray matter, and delayed initial increase but higher peak of ΔM in NAWM in MS.

Figure 5.

Averaged plots of Δ M in deep gray matter (A) and normal-appearing white matter (B), in patients with MS (red) and controls (blue). In MS, deep gray matter Δ M rises later and to a lower peak compared with controls, indicating prolonged bolus arrival time (BAT) and lower cerebral blood flow (CBF). In normal-appearing white matter, Δ M rises later but to a higher peak compared with controls, indicating prolonged BAT but higher CBF. Note that the scale of the y-axis (Δ M) in the two charts is different, with the reduced scale in the normal-appearing white matter compared with deep gray matter indicating a comparative reduction in signal-to-noise in this region.

Association of Bolus Arrival Time and Cerebral Blood Flow with Expanded Disability Status Scale

In patients with MS, longer BAT in NAWM (coefficient=5.2, P<0.001), and deep gray matter (coefficient=7.6, P<0.001) was associated with a higher EDSS score when assessed with co-variates of disease duration and gender. The association between BAT and EDSS retained significance when T2 lesion volume and BPF were additionally entered as co-variates in NAWM (coefficient=4.1, P=0.042) (Figure 6A) and deep gray matter (coefficient=6.0, P=0.011) (Figure 6B) indicating the association of BAT with EDSS was additionally statistically independent from changes in T2 lesion volume and brain atrophy (Figure 6A). There was no significant association between EDSS and CBF in NAWM or deep gray matter with or without BPF and T2 lesion volume as co-variates.

Figure 6.

Scatter plots of expanded disability status score (EDSS) plotted against bolus arrival time (BAT) in the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) (A) and deep gray matter (B). Significance of association was assessed using linear regression with co-variates of gender, disease duration, T2 lesion load, and brain parenchymal fraction. Longer BAT in NAWM and deep gray matter were associated with higher EDSS score.

Association of Bolus Arrival Time and Cerebral Blood Flow with Atrophy and T2 Lesion Load

In patients with MS, reduction in BPF was strongly associated with a reduction in CBF in the deep gray matter (coefficient=3.5, P=0.003), but was not associated with CBF in NAWM (P=0.78), or BAT in the NAWM (P=0.22) or BAT in deep gray matter (P=0.090).

Increased T2 lesion volume was associated with longer BAT (coefficient=0.062, P=0.041) and higher CBF (coefficient=0.15, P=0.041) in the NAWM. In deep gray matter, increased T2 lesion volume was associated with longer BAT (coefficient=0.045, P=0.040), and decreased CBF (coefficient=−0.42, P=0.019).

Relationship between Bolus Arrival Time and Cerebral Blood Flow

In patients with MS, longer BAT in NAWM was associated with increased CBF in NAWM (coefficient=9.0, P=0.006), but reduced CBF in deep gray matter (coefficient=−23, P=0.012). Longer BAT in the deep gray matter was associated with decrease in CBF in the deep gray matter (coefficient=−31, P=0.006) and with increased CBF in the NAWM (coefficient=10, P=0.017). No significant associations were seen between BAT and CBF in controls.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated alteration in overall cerebral hemodynamics in MS. Cerebral circulation time, the difference in the arrival time of ultrasound contrast agent between the carotid artery and cerebral vein, was shown to be significantly prolonged in patients with MS (6.47 versus 5.54 seconds, P<0.001).14 Other studies using MRI contrast methods have shown significant prolongation of mean transit time, a measure of the average time contrast takes to transit from the arterial to venous circulation.15, 16, 17 These studies have indicated that prolongation of cerebral hemodynamics occurs in MS, but were not able to ascertain whether prolonged times were due to arterial or venous factors, as the methods were not able separate their effects. This study extends these observations by demonstrating that the cerebral arterial hemodynamic measure BAT is significantly prolonged in NAWM and deep gray matter in MS, independent of age, gender, and brain atrophy. We also found significant associations between EDSS and BAT in NAWM and deep gray matter, independent of age, gender, BPF, and T2 lesion load. These findings and possible pathophysiological causes will be discussed in turn.

Increased Cerebral Blood Flow and Prolonged Bolus Arrival Time in the Normal-Appearing White Matter in Multiple Sclerosis

We found increased BAT in NAWM suggesting a slower flowing blood in the arteries of patients with MS. The additional finding of increased CBF could suggest that this may be secondary to widespread arteriolar vasodilatation. Arterial vasodilation may explain the increase in CBF seen, and if sufficiently widespread could lead to reduction in flow velocity, as vessel cross sectional area is increased, and flow velocity is inversely proportional to vessel cross sectional area.13 Therefore BAT, measuring the time taken by the blood to reach the capillary bed, could be prolonged.

Widespread arteriolar vasodilation could represent a physiologic response to increased demand, which in the context of MS could be secondary to increased inflammatory and glial cell activity. Infiltration and activation of microglia and lymphocytes are seen in normal-appearing brain tissue in MS,13 and the increased metabolic activity from these cells could lead to increased metabolic demand. Another possible explanation may be that arteriolar vasodilation occurs secondary to dysregulation of the normal mechanisms controlling arteriolar tone. In the context of MS, this could be due to elevations of vasodilatory glutamate and nitric oxide.8, 31

Prolonged Bolus Arrival Time in Deep Gray Matter in Multiple Sclerosis

We found a reduction in CBF in deep gray matter in patients with MS; however, this was not independent of atrophy assessed by BPF. This suggests that reduction in CBF is secondary to reduced metabolic demand secondary to neuroaxonal loss.32 This would concur with a recent large study reporting an association between reduced cortical gray matter CBF and increased T2 lesion load. This study found that of all the variables tested, that white matter lesion load had the strongest association with cortical perfusion reduction,33 suggesting that focal lesions cause neuroaxonal disruption, which leads to a reduction in metabolic demand in the cortical gray matter, and hence reduction in perfusion.

Longer BAT was seen in deep gray matter independent of atrophy suggesting, unlike CBF, that changes in BAT are not directly related to neuroaxonal loss. That neuroaxonal loss per se does not cause alteration in gray matter BAT is also suggested by studies in primary neurodegenerative diseases; e.g. Alzheimer's disease, where reduction in gray matter CBF, thought to be secondary to neuroaxonal loss from neurodegeneration, is not accompanied by alteration in BAT.20, 22 As prolongation of BAT represents reduction in arterial flow velocity, prolonged BAT in deep gray matter could indicate CBF was reduced without commensurate reduction in arterial cross sectional area. One possible cause may be shunting of blood flow to NAWM.13

It is less likely that prolonged BAT in NAWM or deep gray matter represents cerebral venous obstruction or venous hypertension, as large changes in venous pressure have little effect upon BAT.34 Increased circulation time and mean transit time in MS were also not associated with alterations in venous drainage,14, 17 and a reduction in CBF in NAWM would be expected with cerebral venous obstruction or venous hypertension, rather than the increase we observed.

Association Between Prolonged Bolus Arrival Time and Disability

We found that longer BAT in NAWM and deep gray matter was associated with increased disability assessed by the EDSS score; however, CBF was not. As arterial flow velocity is inversely proportional to overall arteriolar cross sectional area, BAT prolongation may reflect both the degree of arteriolar dilatation, and how widespread these changes are across the whole brain. Cerebral blood flow, in contrast, may be sensitive to local changes in tone of the individual feeding arterioles only,13 and increases in CBF in response to vasodilation are limited by the fact that 70% of vascular resistance is at the capillary bed. This hypothesis is speculative however, and requires testing in further work. This could include longitudinal studies, and integrating measurement of CBF and BAT with other measures of tissue injury.

Comparisons with other Studies

No previous studies have examined BAT in MS. Our finding of increased CBF in NAWM is in agreement with a previous ASL study in MS,24 although reduction was seen in other studies using different techniques.15, 35, 36 The differences may be due to patient selection. Patients in our study all had relapsing–remitting MS with a higher median EDSS with similar disease duration compared with studies where a reduction in CBF was reported.15, 35, 36 It is plausible that our relapsing–remitting MS cohort, which has accrued disability at a faster rate will have higher level of inflammation, and glutamate and nitric oxide production in the NAWM, leading to increased CBF. The discrepancy could be due to the lower resolution of our technique, leading to increased partial volume effects from white matter lesions; however, we took care when placing ROIs to avoid lesions, and CBF is increased only in a subset of lesions.16

Previous studies have also shown reduction in CBF in gray matter in patients with MS as seen in this study,24, 33, 36, 37, 38 and association has been reported between reduction in CBF and clinical scores of fatigue and cognitive impairment.36, 37 Whether similar strong associations were seen between brain atrophy and deep gray matter CBF, as seen in this study was not specifically tested.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has a number of limitations, which could be addressed in further work. First, we were not able to monitor physiologic variables like heart rate or end tidal oxygen and carbon dioxide during the MRI session. It is possible that changes in these parameters may occur during the scan, and these may alter the CBF and BAT results seen. However, no subjects had any cardiac or respiratory disease, and the ASL scan was the first scan performed so that any alterations would have to occur in the first 8 minutes of scanning to affect the results. For these reasons, we think that it is unlikely that this had a significant effect upon the results seen here; however, further studies utilizing continuous heart rate monitoring and end tidal oxygen and carbon dioxide levels could address this further.

Second, we did not give contrast, so we were unable to correlate our CBF and BAT measurements in NAWM and deep gray matter with the presence of gadolinium-enhancing lesions. As gadolinium enhancement is a marker of inflammation in acute and reactivated MS lesions,5 assessing the association between the extent of these lesions and abnormalities in BAT and CBF could inform on the relationship between focal inflammation within lesions and the more widespread hemodynamic changes reported in this study.

Third, we were not able to accurately quantify changes in the arterial blood volume. This was because the method used to quantify arterial blood volume in this sequence utilizes velocity sensitive crusher gradients as the means to separate arterial from microvascular blood compartments. As the changes reported in BAT in patients with MS suggest that blood velocity is decreased in this group, and as a proper comparison of arterial blood volume between groups requires unchanged blood velocities to label the components as arterial and microvascular blood compartments in both groups identically, we did not consider the results accurate. Further studies combining ASL with other methods of assessing cerebral blood volume could help clarify the extent the changes in CBF and BAT are associated with alteration in cerebral blood volume, which could help further ascertain the mechanisms behind the changes seen herein.

Finally, a limitation of all ASL MRI methods is that they have a relatively coarse resolution and limited coverage. We took particular care in ROI positioning, using co-registered T1- and T2-weighted higher resolution scans to pick ROI locations, which avoided partial volume effects particularly with lesions and blood vessels, and we did not attempt to measure CBF or BAT in lesions or in cortical gray matter where because of their smaller size, partial volume effects would be more pronounced.

Looking to the future, it will be of interest to study patients with primary and secondary progressive MS, in whom there is less inflammatory disease and more neurodegeneration; studying these patient groups could help further interpret the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying changes observed in this study. Future insights may also be provided by investigating the relationship of ASL measures with other markers of inflammation, metabolism, and microstructural tissue damage including neuroaxonal loss.39, 40

Conclusions

This study is the first to report the use of an ASL perfusion MRI sequence to concurrently measure BAT and CBF in patients with MS. The study extends previous observations of prolongation of cerebral hemodynamics and regional alteration in perfusion by demonstrating longer BAT and increase in CBF in NAWM, and longer BAT in deep gray matter, independent of atrophy. The finding that longer BAT was associated with increased disability, independent of changes in atrophy and T2 lesion load additionally suggests that BAT may be a marker of clinically relevant pathophysiological processes in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The NMR unit where this work was performed is supported by grants from the MS Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Philips Healthcare, and supported by the National Institute for Health Research UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre. The authors would also like to thank all the patients and controls studied for their time and help.

DJT receives salary support for the work on clinical trials from Biogen Idec and Novartis. RK has received fees for participation in advisory boards from Genzyme, Novartis, and Biogen. DHM has received fees for participation in advisory board membership from Biogen Idec, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bayer Schering and has received fees for consultancy from Biogen Idex, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis. DHM also receives royalties from the sale of McAlpine's Multiple Sclerosis, 4th Edition. XG has received fees for consultancy from Philips Healthcare for the ASL method used on this study to help the company put it on their product. DP, ETP, DRA, and CWK report no additional conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by funding from the UK Department of Health National Institute of Heath Research UCLH-UCL Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme (grant code 6DFB). The NMR unit where this work was performed is supported by grants from the MS Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

References

- Kutzelnigg A, Lucchinetti CF, Stadelmann C, Bruck W, Rauschka H, Bergmann M, et al. Cortical demyelination and diffuse white matter injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:2705–2712. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeis T, Graumann U, Reynolds R, Schaeren-Wiemers N. Normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis is in a subtle balance between inflammation and neuroprotection. Brain. 2008;131:288–303. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, Lucchinetti CF, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009;132:1175–1189. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell OW, Rundle JL, Garg A, Komada M, Brophy PJ, Reynolds R. Activated microglia mediate axoglial disruption that contributes to axonal injury in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2010;69:1017–1033. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181f3a5b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soon D, Tozer DJ, Altmann DR, Tofts PS, Miller DH. Quantification of subtle blood-brain barrier disruption in non-enhancing lesions in multiple sclerosis: a study of disease and lesion subtypes. Mult Scler. 2007;13:884–894. doi: 10.1177/1352458507076970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb J, McQuaid S, Mirakhur M, Kirk J. Abnormal endothelial tight junctions in active lesions and normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:154–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider L, Fischer MT, Frischer JM, Bauer J, Höftberger R, Botond G, et al. Oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 2011;134:1914–1924. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Nelson S, Pelletier D. Evidence of elevated glutamate in multiple sclerosis using magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 T. Brain. 2005;128:1016–1025. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuerfel J, Bellmann-Strobl J, Brunecker P, Aktas O, McFarland H, Villringer A, et al. Changes in cerebral perfusion precede plaque formation in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal perfusion MRI study. Brain. 2004;127:111–119. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom KA, Anthony DC, Blamire AM, Waters S, Styles P, Perry VH, et al. MRI reveals that early changes in cerebral blood volume precede blood-brain barrier breakdown and overt pathology in MS-like lesions in rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:204–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serres S, Anthony DC, Jiang Y, Broom KA, Campbell SJ, Tyler DJ, et al. Systemic inflammatory response reactivates immune-mediated lesions in rat brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4820–4828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0406-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serres S, Bristow C, de Pablos RM, Merkler D, Soto MS, Sibson NR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals therapeutic effects of interferon-beta on cytokine-induced reactivation of rat model of multiple sclerosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:744–753. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas DA, Jones SR, Devor A, Huppert TJ, Dale AM. A vascular anatomical network model of the spatio-temporal response to brain activation. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1116–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M, Morra VB, Di Donato O, Maglio V, Lanzillo R, Liuzzi R, et al. Multiple sclerosis: cerebral circulation time. Radiology. 2012;262:947–955. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11111239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M, Saindane AM, Ge Y, Babb JS, Johnson G, Mannon LJ, et al. Microvascular abnormality in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: perfusion MR imaging findings in normal-appearing white matter. Radiology. 2004;231:645–652. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313030996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Law M, Johnson G, Herbert J, Babb JS, Mannon LJ, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MR imaging of multiple sclerosis lesions: characterizing hemodynamic impairment and inflammatory activity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1539–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaci FG, Marziali S, Meschini A, Fornari M, Rossi S, Melis M, et al. Brain hemodynamic changes associated with chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency are not specific to multiple sclerosis and do not increase its severity. Radiology. 2012;265:233–239. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhu X, Feinberg D, Guenther M, Gregori J, Weiner MW, et al. Arterial spin labeling MRI study of age and gender effects on brain perfusion hemodynamics. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:912–922. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E, Lim T, Golay X. Model-free arterial spin labeling quantification approach for perfusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:219–232. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiura T, Hiwatashi A, Noguchi T, Yamashita K, Ohyagi Y, Monji A, et al. Arterial spin labelling at 3-T MR imaging for detection of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:2819–2825. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen ET, Mouridsen K, Golay X. The QUASAR reproducibility study, part II: results from a multi-center arterial spin labeling test-retest study. Neuroimage. 2010;49:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak HKF, Chan Q, Zhang Z, Petersen ET, Qiu D, Zhang L, et al. Quantitative assessment of cerebral hemodynamic parameters by QUASAR arterial spin labeling in Alzheimer's disease and cognitively normal elderly adults at 3-Tesla. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:33–44. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu M, Maguire RP, Arora J, Planeta-Wilson B, Weinzimmer D, Wang J, et al. Arterial transit time effects in pulsed arterial spin labeling CBF mapping: insight from a PET and MR study in normal human subjects. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:374–384. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid W, Parkes LM, Ingle GT, Chard DT, Toosy AT, Altmann DR, et al. Abnormalities of cerebral perfusion in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1288–1293. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.026021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman C, Reingold S, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen J, Filippi M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ourselin S, Roche A, Subsol G, Pennec X, Ayache N. Reconstructing a 3D structure from serial histological sections. Image Vision Comput. 2001;19:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ourselin S, Stefanescu R, Pennec X. Robust registration of multi-modal images: towards real-time clinical applications. MICCAI. 2002;2489:140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi AM, Abolmaesumi P, Wild C, Johnsrude IS. A validation framework for probabilistic maps using Heschl's gyrus as a model. Neuroimage. 2010;50:z532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikse J, Petersen E, van Laar P, Golay X. Cerebral border zones between distal end branches of intracranial arteries: MR imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:572–580. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461062100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rejdak K, Eikelenboom MJ, Petzold A, Thompson EJ, Stelmasiak Z, Lazeron RHC, et al. CSF nitric oxide metabolites are associated with activity and progression of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:1439–1445. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142043.32578.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese M, Liu S, Babb JS, Mannon LJ, Grossman RI, Gonen O. Three-dimensional proton spectroscopy of deep gray matter nuclei in relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology. 2004;63:170–172. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133133.77952.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann M, Achtnichts L, Hirsch JG, Naegelin Y, Gregori J, Weier K, et al. 3D GRASE arterial spin labelling reveals an inverse correlation of cortical perfusion with the white matter lesion volume in MS. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1570–1576. doi: 10.1177/1352458512441984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish RS, Amiridze NS. Brain perfusion abnormalities in patients with compromised venous outflow. J Neurol. 2011;258:1445–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhya S, Johnson G, Herbert J, Jaggi H, Babb JS, Grossman RI, et al. Pattern of hemodynamic impairment in multiple sclerosis: dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MR imaging at 3.0 T. Neuroimage. 2006;33:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese M, Adhya S, Johnson G, Babb JS, Miles L, Jaggi H, et al. Perfusion magnetic resonance imaging correlates of neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:164–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese M, Park S-J, Johnson G, Babb JS, Miles L, Jaggi H, et al. Deep gray matter perfusion in multiple sclerosis: dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:196–202. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AW, Johnson G, Babb JS, Herbert J, Grossman RI, Inglese M. White matter hemodynamic abnormalities precede sub-cortical gray matter changes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;282:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paling D, Golay X, Wheeler-Kingshott C, Kapoor R, Miller D. Energy failure in multiple sclerosis and its investigation using MR techniques. J Neurol. 2011;258:2113–2127. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambron M, D'Haeseleer M, Laureys G, Clinckers R, Debruyne J, Keyser JD. White-matter astrocytes, axonal energy metabolism, and axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:413–424. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]