Abstract

This study investigated the changes in cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) signals, cerebrovascular and ventilatory responses to hypoxia and CO2 during altitude exposure. At sea level (SL), after 24 hours and 5 days at 4,350 m, 11 healthy subjects were exposed to normoxia, isocapnic hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hypocapnia. The following parameters were measured: prefrontal tissue oxygenation index (TOI), oxy- (HbO2), deoxy- and total hemoglobin (HbTot) concentrations with NIRS, blood velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCAv) with transcranial Doppler and ventilation. Smaller prefrontal deoxygenation and larger ΔHbTot in response to hypoxia were observed at altitude compared with SL (day 5: ΔHbO2−0.6±1.1 versus −1.8±1.3 μmol/cmper mm Hg and ΔHbTot 1.4±1.3 versus 0.7±1.1 μmol/cm per mm Hg). The hypoxic MCAv and ventilatory responses were enhanced at altitude. Prefrontal oxygenation increased less in response to hypercapnia at altitude compared with SL (day 5: ΔTOI 0.3±0.2 versus 0.5±0.3% mm Hg). The hypercapnic MCAv and ventilatory responses were decreased and increased, respectively, at altitude. Hemodynamic responses to hypocapnia did not change at altitude. Short-term altitude exposure improves cerebral oxygenation in response to hypoxia but decreases it during hypercapnia. Although these changes may be relevant for conditions such as exercise or sleep at altitude, they were not associated with symptoms of acute mountain sickness.

Keywords: altitude illness, carbon dioxide, cerebral hemodynamic, near-infrared spectroscopy, oxygenation

Introduction

Sufficient oxygenation of brain tissue is critical to avoid severe symptoms and life-threatening consequences during hypoxic exposure.1 Oxygen delivery to the brain is dependent on both arterial O2 content and cerebral perfusion. During hypoxic exposure, the cerebral blood flow (CBF) greatly depends on the balance between the O2 and the carbon dioxide (CO2) cerebrovascular responses (CVRs), as reduced arterial oxygenation is accompanied by hyperventilation-induced changes in arterial CO2.

Global CBF at high altitude has been measured by using inert tracers such as the Kety–Schmidt nitrous oxide washout method2, 3 or the 133xenon technique.4 Cerebrovascular responses to O2 and CO2 have mostly been measured by using transcranial Doppler (TCD).5 Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been proposed as an attractive and complementary methodology to TCD to measure cerebrovascular reactivity.6 Compared with TCD, cerebral NIRS has the advantage to provide insights into local tissue hemodynamics compared with the assessment of perfusion in large vessels by TCD and to measure not only the amount of blood under the probe (total hemoglobin content, HbTot) but also the respective concentration changes of oxy- (HbO2) and deoxy- (HHb) hemoglobin reflecting cerebral tissue oxygenation.7

Cerebral oxygenation measured by NIRS is reduced when arterial oxygenation drops during acute hypoxic exposure (10 minutes to 10 hours8, 9, 10). After 2 to 5 days of hypoxic exposure, the cerebrovascular response to hypoxia measured by TCD was shown to be enhanced, i.e. blood velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCAv) increased to a greater extent in response to hypoxia.11, 12 It remains to determine whether an enhanced hypoxic cerebrovascular response during prolonged hypoxic exposure (several days) may induce a better preservation of cerebral oxygenation in response to hypoxia and consequently a better acclimatization to high altitude.

Controversial results are available regarding changes in the cerebrovascular response to CO2 after several days at high altitude, with unchanged,13, 14, 15 reduced,16 or increased4, 17 responses to hypercapnia, and reduced13 or increased15, 16, 18 responses to hypocapnia. Some studies showed that in response to hypercapnia at SL, the enhanced MCAv is accompanied by parallel changes in NIRS signal, i.e. a large increase in HbO2 and a small decrease in HHb concentrations.6, 19 Changes in the cerebral tissue hemodynamics measured by NIRS in response to hyper- and hypocapnia during prolonged hypoxic exposure have never been investigated and may help to better understand cerebral adaptations and acclimatization to high altitude.

Cerebral oxygenation represents a vital parameter that can be challenged during prolonged hypoxic exposure such as at high altitude, under resting conditions but also during exercise and sleep that are able to induce profound changes in blood gases.20, 21 Whether cerebral oxygenation during changes in arterial CO2 differs after prolonged hypoxic exposure is also important to determine, as high-altitude exposure is associated with hypocapnia (at rest and even more during physical exercise) but also with periods of relative hypercapnia (during sleep apnea as frequently observed at high altitude).13 In addition, changes in cerebral perfusion and oxygenation are connected with the ventilatory response, which is an important factor for altitude acclimatization.22 In a recent study,23 we showed by using arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging at SL that CBF and cerebrovascular response to hypercapnia were increased and reduced, respectively, immediately after 6 days at 4,350 m. By using NIRS during the stay at high altitude, the present study investigated in the same subjects after acute (24 hours) and short-term (5 days) exposure to 4,350 m O2- and CO2-induced changes in cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. Based on previous reports regarding O2- and CO2-induced changes in MCAv at altitude,11, 13, 16, 23 we hypothesized that short-term exposure to high altitude would (i) increase cerebral perfusion and as a consequence cerebral oxygenation in response to hypoxia and (ii) reduce MCAv and therefore cerebral oxygenation in response to arterial CO2 changes. To address the potential link between changes in cerebrovascular and ventilatory responses at altitude,13, 16 we also tested the hypothesis that changes in cerebral perfusion and oxygenation would correlate with changes in ventilatory responses.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Eleven male subjects (mean±s.d. age 28±8 years, height 176±7 cm, weight 71±7 kg) participated in this study after giving written, informed consent. All participants underwent full medical screening before inclusion to rule out respiratory, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases. Subjects were usual recreational climbers with no history of severe acute mountain sickness (AMS) during previous high-altitude ascents and were unacclimatized to high altitude (no sojourn above 1,500 m over the past 3 months). They received no treatment to prevent or treat AMS throughout the study. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (CPP Grenoble Sud Est V) and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki (Clinical trial registration: NCT01565603).

Protocol

All subjects performed three experimental sessions. The first one (at SL) was performed at the Grenoble University Hospital (elevation: 212 m). Then, subjects underwent helicopter transport at midday (±2 hours) to be dropped 10 minutes later at 4,350 m (Observatoire Vallot, Mont Blanc, Chamonix, France). The second experimental session (D1) was performed the following day after 1 night spent at 4,350 m. The third session (D5) was performed after 5 days at 4,350 m. From D1 to D5, subjects stayed in the Observatoire Vallot without further ascent. During each experimental session, subjects were installed comfortably in a semi-recumbent position. They had to stay quiet and to avoid any movement for the entire test duration (∼90 minutes). Each subject performed the three experimental sessions at the same time of the day±2 hours. Subjects had no heavy meal within 2 hours before the tests and ingested no caffeine or alcohol at least 24 hours before the tests.

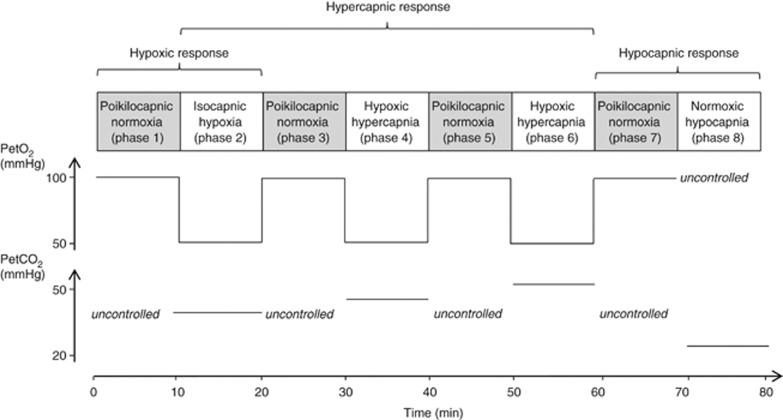

To assess ventilatory and cerebral hemodynamic responses, subjects inhaled gas mixtures with various inspiratory O2 and CO2 fractions delivered by a modified Altitrainer 200 (SMTEC, Nyon, Switzerland) via a face mask and were masked for the gas mixture composition. Inspiratory O2 and CO2 were adjusted to reach the target values for end-tidal partial pressure of O2 (PetO2) and CO2 (PetCO2) according to the modified ‘Leiden proposal'.24 The protocol (Figure 1) consisted of eight consecutive 10-minutes phases. In phases 1, 3, 5, and 7, target PetO2 was 100 mm Hg and CO2 was 0 (poikilocapnic normoxia). These phases allowed (i) avoidance of prolonged sustained hypoxic or hypercapnic exposure that may induce some ventilatory or cerebrovascular adaptations (e.g. ventilatory decline24) and (ii) repetitive measurement of baseline values to be compared with the subsequent phase (see below), therefore avoiding to compare measurements performed far from each other. In phases 2, 4, and 6, target PetO2 was 55 mm Hg (similar to values observed at ∼4,300 m while breathing ambient air). Target PetCO2 in phases 2, 4, and 6 was respectively 0, 5, and 12 mm Hg above the value measured at the end of phase 1. These three phases thus represent isocapnic hypoxia, hypoxic hypercapnia +5 mm Hg, and hypoxic hypercapnia +12 mm Hg conditions, respectively. In phase 8, to measure hypocapnic responses, subjects inhaled the same gas mixture as in phase 7 but were instructed and given verbal feedback to slightly hyperventilate to lower and then maintain PetCO2 at 15 mm Hg below the value measured at the end of phase 1.

Figure 1.

Description of the main phases of the protocol to measure ventilatory and cerebral hemodynamic responses with simultaneous changes in end-tidal O2 (PetO2) and CO2 (PetCO2) partial pressures at SL and at high altitude. End-tidal CO2 partial pressure values illustrate typical SL measurements. During poikilocapnic conditions (phases 1, 3, 5, 7), PetCO2 was uncontrolled; during the isocapnic condition (phase 2), PetCO2 was maintained at the same level as the end of phase 1, whereas during hypercapnic conditions (phases 4 and 6), PetCO2 was increased by +5 and +12 mm Hg above the value at the end of phase 1. See Materials and Methods for more details.

Ventilation, PetO2, PetCO2, arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) by finger pulse oximetry, and heart rate were continuously measured and recorded using an automated metabolic cart (Quark b2, Cosmed, Rome, Italy). Before each test, ambient conditions were measured, then the flow meter and gas sensors were calibrated by using a 2-L syringe and gases of known concentrations. All parameters were averaged over the last minute of each phase and used to calculate the hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses, i.e. the slope of the linear regression between changes in minute ventilation and the reduction in PetO2 (in l minute·mm Hg) or SpO2 (in l minute·%SpO2) and the increase in PetCO2 (in %·mm Hg), respectively. Transcranial Doppler and cerebral NIRS signals were also continuously recorded during the experimental sessions. Room air temperature during the test sessions was 23±2°C at SL, 21±2°C at D1 and 22±1°C at D5 at altitude.

Transcranial Doppler

Two different Doppler devices were used to assess on one hand MCAv changes during periods of gas mixture inhalation and on the other hand absolute MCAv under ambient conditions at sea level (SL) and at altitude. Blood velocity in the middle cerebral artery changes in response to gas mixture inhalation were measured with a Doppler instrument operating at 2 MHz (Wakie, Atys Medical, Soucieu en Jarrest, France). With this device, the Doppler probe could be secured by a headband maintaining the same insonation position throughout the experimental session. In all subjects, the right MCA was insonated through the transtemporal window at a depth of 50 to 60 mm. Mean right MCAv (in cm/second) was acquired over each heartbeat and averaged over the last minute of each phase of the protocol (see above). Measurements corresponding to isocapnic hypoxia, hypoxic hypercapnia+5 and+12 mm Hg and hypocapnia were expressed as a percentage of the respective previous poikilocapnic normoxic periods and used to calculate the hypoxic, hypercapnic, and hypocapnic cerebrovascular responses (TCD), i.e. the slope of the linear regression between changes in MCAv and the reduction in PetO2 (in %·mm Hg) or SpO2 (in %·SpO2), the increase in PetCO2 (in %·mm Hg) and the reduction in PetCO2 (in %·mm Hg), respectively. Due to technical problem, TCD measurements at D1 were available in five subjects only.

Absolute MCAv while breathing ambient air was assessed using a 5 to 1 MHz two-dimensional Transducer CX-50 (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands). This device was used for absolute MCAv measurement under ambient air to have a better reliability for between-day comparisons of absolute TCD MCAv values at rest.25 The clinoid process of the sphenoid bone and the brain stem were initially identified. Color-coded sonography allowed identifying the circle of Willis. The M1 segment of the right MCA was identified and manual angle correction was applied to measure mean right MCAv (in cm/second) by the inbuilt software.

Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

Cerebral oxygenation was monitored with a four-wavelength (775, 810, 850, 905 nm) NIRS device (NIRO-300, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). The optodes consisted of one emitter and one receiver (that includes three separate photo detectors) housed in a black holder. The holder was stuck on the skin with double-sided adhesive tape to ensure no change in its relative position and to minimize the intrusion of extraneous light and the loss of transmitted NIR light from the field of interrogation. An optical differential pathlength factor that takes into account light scattering in tissue is often inserted in the modified Lambert–Beer law used to describe optical attenuation. We decided not to use differential pathlength factor values as they may vary from one wavelength to another, across subjects, and even over time for a given subject and tissue.26 The optodes were positioned over the left prefrontal cortical area at the midpoint between Fp1-F3 landmarks of the international EEG 10 to 20 system electrode placement. The inter-optode distance was 4 cm and the optode holder was covered and maintained with a homemade black Velcro headband. Cerebral NIRS data were collected at time resolution of 0.5 seconds. Measurements corresponding to isocapnic hypoxia, hypoxic hypercapnia+5 and+12 mm Hg, and hypocapnia were expressed as relative concentration changes (Δμmolcm) from the respective previous poikilocapnic normoxic periods (see Figure 2) and used to calculate the hypoxic, hypercapnic, and hypocapnic NIRS responses, i.e. the slope of the linear regression between changes in NIRS signal and the reduction in PetO2 (in μmol/cm permm Hg) or SpO2 (in μmol/cm per·%SpO2), the increase in PetCO2 (in μmol cm per·mm Hg) and the reduction in PetCO2 (in μmol cm per mm Hg), respectively. The following NIRS parameters were measured: (Δ(HbO2)), (Δ(HHb)), and (Δ(HbTot)=(HbO2)+(HHb)) changes. Total hemoglobin reflects changes in tissue blood volume within the illuminated area, (HHb) and (HbO2) are known to be reliable estimator of changes in tissue oxygenation status.7 In addition, the multidistance spatially resolved tissue oximeter we used (NIRO-300) could quantify tissue oxyhemoglobin saturation directly as a tissue oxygenation index (TOI, expressed in %), which is a surrogate measure for cerebrovenous saturation when applied to the head.

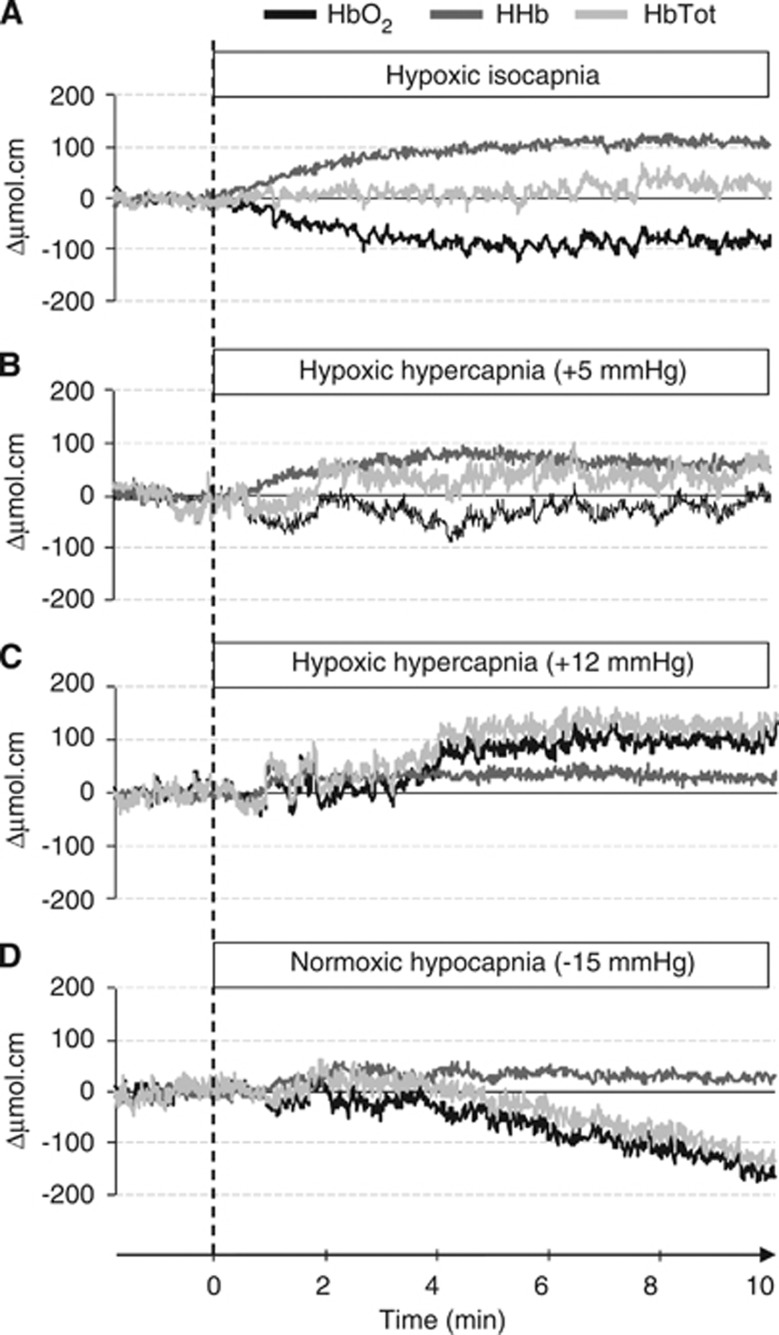

Figure 2.

Typical changes in prefrontal oxy-(HbO2), deoxy-(HHb) and total hemoglobin (HbTot) concentrations in response to hypoxic isocapnia (A), hypoxic hypercapnia +5 (B), and +12 mm Hg (C), and normoxic hypocapnia (D), from a baseline in poikilocapnic normoxia. Oxyhemoglobin is black, HHb is dark gray and HbTot is light gray. Raw data are presented for a representative subject at SL.

Symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness and Cardiorespiratory Parameters under Ambient Air

Subjects were asked every morning at altitude to complete self-reported questionnaires for AMS evaluation according to the Lake Louise Score (, five items)27 and the cerebral subscore of the Environmental Symptom Questionnaire (AMS-C, 11 items).28 The presence of AMS was defined as Lake Louise Score⩾3 and AMS-C⩾0.7. Heart rate and non-invasive blood pressure (Dinamap, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and SpO2 using finger pulse oximetry (Biox 3740 Pulse Oximeter, Ohmeda, Louisville, CO, USA) were measured under resting conditions while breathing ambient air.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the statistical significance of temporal changes during the study period (SL, D1, D5) was performed using one-way analysis of variance for repeated measurements (StatView SE program, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). When a significant main effect was found, post hoc analysis was performed with Fisher's LSD tests. Correlations were performed using linear regression and Pearson's coefficient. For all statistical analyses, a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 was used as the cut-off for significance. All descriptive statistics presented are mean values±s.d.

Results

Hypoxic Responses

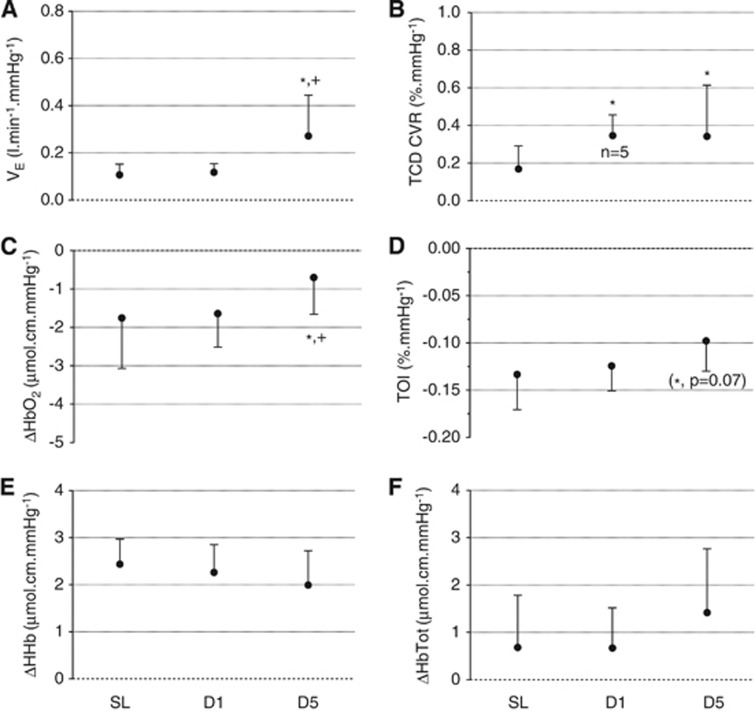

(Figure 3 and Figures 1 and 2 in Supplementary Online Data) The hypoxic ventilatory response was significantly increased at D5 compared with SL and D1 (ANOVA main effect of time: F=6.92, P=0.005, when expressed per mm Hg PetO2 reduction; F=8.14, P=0.003, when expressed per % SpO2 reduction). The hypoxic TCD CVR was significantly increased at D1 and D5 compared with SL (F=4.17, P=0.031, per mm Hg PetO2 reduction; F=5.30, P=0.014, per % SpO2 reduction). The hypoxia-induced HbO2 decrease per mm Hg of PetO2 reduction was significantly smaller at D5 compared with SL and D1 (F=3.94, P=0.036) and a similar tendency was observed for TOI (F=2.98, P=0.074). The increase in HbTot per % of SpO2 reduction was significantly larger at D5 compared with SL and D1 (F=5.90, P=0.027). No other significant difference in NIRS parameters was observed for hypoxic responses.

Figure 3.

Hypoxic responses: Ventilatory (VE, panel A), transcranial Doppler (TCD) (TCD cerebrovascular responses (CVR), panel B) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) (oxyhemoglobin (HbO2), panel C; tissue oxygenation index (TOI), panel D; deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), panel E; total hemoglobin (HbTot), panel F) responses to isocapnic hypoxia at sea level (SL), at day 1 (D1) and 5 (D5) at altitude. Changes in VE, TCD CVR and NIRS variables are expressed per mm Hg of change in end-tidal O2 partial pressure. *significantly different from SL;+significantly different from D1.

At D1, the ventilatory response was significantly correlated with TOI (per % SpO2 reduction; r2=−0.60, P=0.005) and HbTot (per mm Hg PetO2 reduction; r2=−0.48, P=0.004) responses, i.e. the greater the ventilatory response, the greater the TOI reduction and te smaller the HbTot increase. At D5, the TCD CVR was significantly correlated with HbO2 (per mm Hg PetO2 reduction; r2=−0.58, P=0.007) and HbTot (per mm Hg PetO2 reduction; r2=−0.39, P=0.039) responses, i.e. the greater the TCD CVR, the larger the HbO2 decrease and the smaller the HbTot increase.

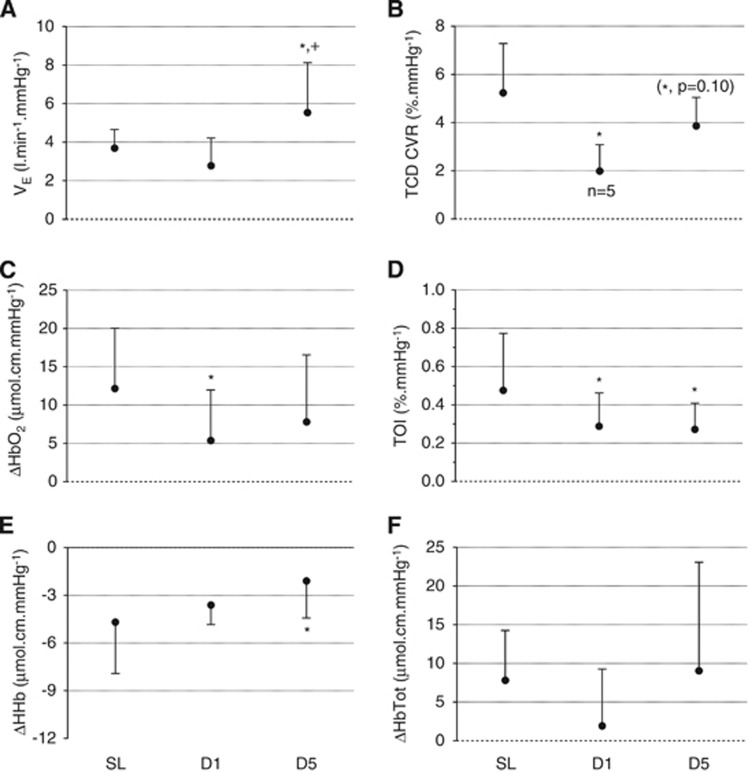

Hypercapnic Responses

(Figure 4 and Figure 3 in Supplementary Online Data) The hypercapnic ventilatory response was significantly increased at D5 compared with SL and D1 (F=14.60, P=0.001). The hypercapnic TCD CVR was significantly reduced at D1 (and tended to be reduced at D5) compared with SL (F=5.90, P=0.027). The HbO2 increase per mm Hg of PetCO2 increase was significantly smaller at D1 compared with SL (F=4.26, P=0.029), the TOI increase per mm Hg of PetCO2 increase was significantly smaller at D1 and D5 compared with SL (F=4.14, P=0.031) and the HHb reduction per mm Hg of PetCO2 increase was significantly smaller at D5 compared with SL (F=3.85, P=0.041). No other significant difference in NIRS parameters was observed for hypercapnic responses.

Figure 4.

Hypercapnic responses: Ventilatory (VE, panel A), TCD (TCD CVR, panel B) and NIRS (oxyhemoglobin (HbO2), panel C; tissue oxygenation index (TOI), panel D; deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), panel E; total hemoglobin (HbTot), panel F) responses to hypercapnia (expressed per mm Hg of change in end-tidal CO2 partial pressure) at sea level (SL), at day 1 (D1) and 5 (D5) at altitude. *significantly different from SL;+significantly different from D1.

At D5, the TCD CVR was significantly correlated with the TOI response (r2=0.71, P=0.002), i.e. the smaller the TCD CVR, the smaller the TOI increase.

Hypocapnic Responses

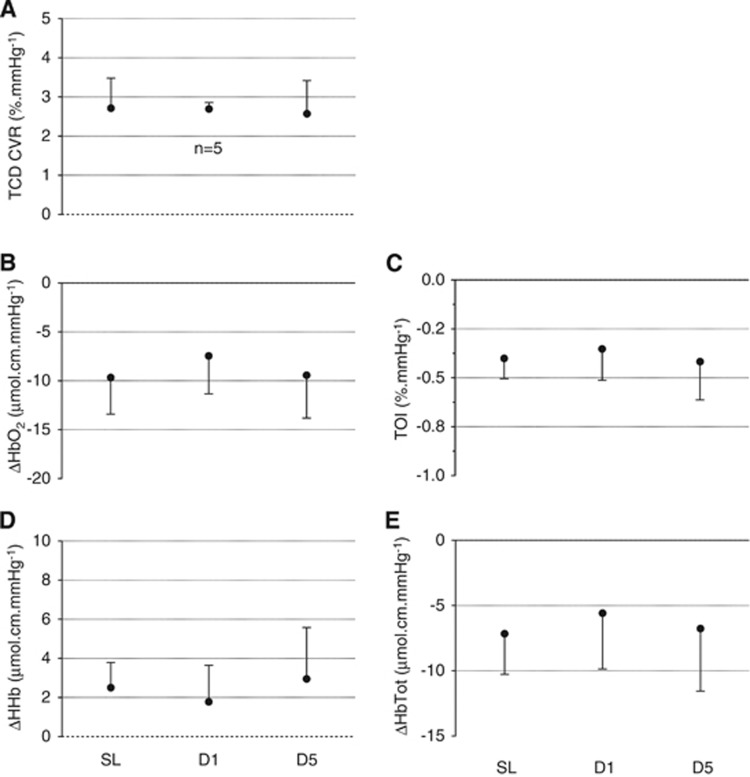

(Figure 5 and Figure 4 in Supplementary Online Data) The hypocapnic TCD CVR and NIRS responses did not change significantly throughout the protocol.

Figure 5.

Hypocapnic responses: TCD (TCD CVR, panel A) and NIRS (oxyhemoglobin (HbO2), panel B; tissue oxygenation index (TOI), panel C; deoxyhemoglobin (HHb), panel D; total hemoglobin (HbTot), panel E) responses to hypocapnia (expressed in mm Hg of change in end-tidal CO2 partial pressure) at sea level (SL), at day 1 (D1) and 5 (D5) at altitude.

Symptoms, Cardiorespiratory Parameters, Tissue Oxygenation Index and Blood Velocity in the Middle Cerebral Artery under Ambient Air

(Table 1) Symptoms of AMS were significantly increased at D1 compared with SL. At altitude while breathing ambient air, PetO2, PetCO2, SpO2, and TOI were significantly reduced whereas TCD MCAv values at rest, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure were significantly increased. No significant correlation was observed between symptoms of AMS or cardiorespiratory parameters under ambient air conditions and ventilatory, TCD, and NIRS responses to hypoxia, hypercapnia, or hypocapnia.

Table 1. Symptoms, cardiorespiratory, and cerebrovascular parameters while breathing ambient air at sea level and at altitude.

| SL | D1 | D5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLS | 1±1 | 5±3a | 1±1b |

| ESQ-c | 0.01±0.12 | 0.80±0.85a | 0.07±0.10b |

| PetO2 (mm Hg) | 102±4 | 47±2a | 50±6a,b |

| PetCO2 (mm Hg) | 41±5 | 34±2a | 31±3a,b |

| SpO2 (%) | 97±1 | 87±2a | 88±1a |

| TOI (%) | 76±4 | 65±3a | 66±4a |

| TCD MCAv (cm/second) | 55±8 | 64±8a | 66±9a |

| HR (b.p.m.) | 61±8 | 73±12a | 78±16a |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 104±6 | 107±7 | 116±7a,b |

D1, first day at 4,350 m; D5, fifth day at 4,350 m; ESQ-c, cerebral subscore of the environmental symptom questionnaire; HR, heart rate; LLS, Lake Louise score; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCAv, middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity; PetO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure; PetO2, end-tidal oxygen partial pressure; SL, sea level, SpO2, arterial oxygen saturation; TOI, cerebral tissue oxygenation index; TCD, transcranial Doppler.

Values are mean±s.d.

significantly different from SL.

significantly different from D1 (P⩽0.05).

Discussion

This study reports changes in cerebral NIRS signals together with ventilatory and TCD responses during hypoxic, hyper-, and hypocapnic gas inhalation at high altitude. Compared with SL, high-altitude exposure induced (i) smaller prefrontal deoxygenation in response to isocapnic hypoxia, and lower prefrontal oxygenation increase in response to hypercapnia, (ii) larger hypoxic and smaller hypercapnic TCD CVR, and (iii) greater hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses. In contrast, no change in NIRS and TCD hypocapnic responses was observed at high altitude. These results suggest that after several days at altitude, brain oxygenation is better preserved when arterial oxygenation drops whereas it is reduced during hypercapnia. Although these changes may be relevant for conditions such as exercise or sleep at altitude, their relationships with symptoms of AMS remain to be clarified.

Hypoxic Responses

The isocapnic hypoxic ventilatory and TCD responses show robust increases after 5 days at high altitude. Similar results were observed after several days in hypoxia (e.g.11, 12, 29). This increase was observed both as a function of PetO2 (per mm Hg, Figure 1) and SpO2 (per %, Figure 1 in Supplementary Online Data). As O2 arterial saturation is not the stimulus to the oxygen sensors at the carotid bodies or cerebrovascular levels, it appears more appropriate to express these responses as a function of mm Hg PetO2.24 The present study indicates that prefrontal oxygenation (HbO2) is less impaired during an isocapnic hypoxic challenge after 5 days (but not after 24 hours) at 4,350 m. Only one study30 measured cerebral deoxygenation during hypoxic breathing by NIRS before and after five nocturnal hypoxic exposures (8 hours/day, simulated altitude 4,300 m) and reported no significant change in prefrontal deoxygenation (assessed from an index of regional oxygen saturation, SrO2). This suggests that the amount of time spent in hypoxia may have been insufficient to induce significant improvement in cerebral oxygenation or that indexes of cerebral oxygenation (TOI in the present study and SrO2 in Kolb et al9 study) are less sensitive to altitude-induced changes in cerebral oxygenation than HbO2 concentration.

Changes in NIRS hemoglobin concentrations expressed as a function of PetO2 can be influenced by changes in the oxygen dissociation curve as observed at high altitude. These changes typically consist in a left shift due to hypocapnia and alkalosis associated with hyperventilation during acute exposure followed by a progressive return to SL values or even a right shift with, among other mechanisms, an increase in 2,3-DPG during full acclimatization.31 As the oxygen dissociation curve could not be measured within the present study, one can only speculate about a left shift of the oxygen dissociation curve at D1, whereas at D5 it was probably more similar to SL. Oxyhemoglobin (and TOI) reduction was significantly smaller at altitude when expressed as a function of PetO2 (Figure 1) but this effect did not reach significance when expressed as a function of SpO2 (Figure 1 in Supplementary Online Data). This suggests that part of the improved NIRS cerebral oxygenation in response to hypoxia at D5 was due to the smaller % SpO2 decrease during the hypoxic challenge (−9±2% at SL, −7±3% at D1 and −5±1% at D5, P⩽0.001) when PetO2 was reduced from 100 to 55 mm Hg. Regarding HbTot, however, a larger increase in hypoxia when expressed as a function of % SpO2 reduction (and a similar trend when expressed per mm Hg PetO2, P=0.14) suggests an increased local perfusion in response to hypoxia after 5 days of high-altitude exposure. Overall, similar tendencies were observed regarding changes in hypoxic NIRS responses when expressed as a function of PetO2 or SpO2 (Figure 3 and Figure 1 in Supplementary Online Data), suggesting that other factors than modifications of the oxygenation dissociation curve probably underlie the improved prefrontal oxygenation and perfusion in response to hypoxia at altitude. Systemic cardiovascular adaptations (as shown by the increased heart rate and mean arterial pressure, Table 1), neuronal pathways, circulating and endothelium-derived vasoactive stimuli are other potential mechanisms able to explain changes in cerebrovascular reactivity at high altitude.5, 32

The HbO2 and HbTot isocapnic hypoxic responses at D5 correlated with the TCD CVR, but these correlations were somehow unexpected, and it is difficult to explain why subjects with small NIRS responses have high TCD CVR. Transcranial Doppler evaluates changes in flow in a large artery (MCA) supplying several regions of the brain in addition to the frontal lobe. In contrast, NIRS HbTot is a volumetric index that is not directly dependent on blood flow but is rather influenced by local capillary vasodilation and venous compartment compliance. Peltonen et al10 observed no correlation between MCAv and HbTot responses to acute hypoxia. The absence of correlation between TCD CVR and NIRS signals at SL and D1 shows that both responses are overall poorly related.

The correlations between the hypoxic ventilatory response and the NIRS signals at D1 indicate that a large cerebral deoxygenation is associated with brisk hypoxic ventilatory response. Although the ventilatory response to hypoxia is mostly initiated by the carotid bodies, central oxygen sensors may also be involved.24 The latter exposed to more severe hypoxia as shown in the prefrontal cortex may stimulate ventilation to a greater extent. This is, however, hypothetical, and it remains unclear why such a relationship was obtained at D1 only. Peltonen et al10 reported at SL no correlation between hypoxic ventilatory, MCAv, and NIRS responses. The present results suggest that this is also essentially true at high altitude and that each of these responses relies on distinct mechanisms and regional adaptations (e.g. peripheral versus central chemoreceptors, large cerebral artery versus regional cortical oxygenation). Interestingly, the change in hypoxic TCD CVR occurred as soon as D1 (TCD CVR at D1 was available in five subjects only who had all larger values at D1 compared with SL) whereas significant changes in ventilatory and NIRS responses were observed at D5 only. Early cerebral adaptations may mostly depend on changes in blood gases, cerebrospinal fluid pH, and autonomic nervous system, whereas later adaptations may also include hematological modifications, angiogenesis, and alterations in the cerebral metabolic rate.32 Smith et al33 recently reported an increase in O2 cerebral metabolic rate (CMRO2) assessed by MRI methods during sustained hypoxia at high altitude (2 days at 3,800 m) that might be driven by the reduced arterial CO2 content associated with the hypoxic ventilatory response. In the present study, as PetCO2 was reduced at altitude, the cerebral responses were possibly measured from a larger initial CMRO2 at altitude compared with SL. Because NIRS signal is affected by cerebral perfusion but also by O2 extraction and metabolic rate, altitude-induced changes in CMRO2 might have influenced changes in NIRS signal at altitude. However, altered CMRO2 at high altitude is not a universal finding2, 3 and as we measured changes in NIRS signals relative to normoxic measurements made at the same altitude (i.e. at SL or at 4,350 m), the effect of changes in CMRO2 on the present results remains hypothetical. The present study does not provide direct evidence in support of any particular mechanisms regulating ventilatory and cerebral hypoxic responses at high altitude.

The improved tissue oxygenation in response to transient isocapnic hypoxic challenge did not translate into better prefrontal oxygenation under ambient air from D1 to D5 (based on TOI values, Table 1). This may be due to the insufficient sensitivity of TOI to changes in cerebral oxygenation (compared with HbO2 for instance, as indicated above) or to the concomitant influence of hypoxia and hypocapnia on cerebral oxygenation under ambient air at altitude. The increase in hypoxic TCD CVR may be one of the mechanisms leading to increased MCAv under ambient air at altitude (Table 1). Although both hypoxic TCD CVR and ambient air MCAv were significantly increased as soon as D1, no correlation was observed between both parameters. In a study parallel to the present one, we have observed that absolute CBF (measured in the same subjects by arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging) is still enhanced when measured at SL within a few hours (6±2 hours) after descent from several days at high altitude,23 suggesting that hypoxia per se is not the only factor influencing CBF changes at altitude.

Carbon dioxide Responses

The hypercapnic ventilatory response was significantly increased after 5 days at 4,350 m in accordance with previous observations in chronic hypoxia.14, 16, 17 The literature provides contrasted results regarding the effect of prolonged hypoxic exposure on the TCD CVR to CO2 (see Introduction). This may be due at least in part to differences in methodological approaches, with for instance inverse changes observed within the same altitude stay when measured with a rebreathing17 or a steady-state16 protocol. In the present study, we assessed steady-state hypercapnic responses under hypoxia to provide data relevant to conditions at altitude (e.g. sleep, exercise) whereas several other studies have measured the hypercapnic TCD CVR in hyperoxia (e.g.11, 12, 16).

An increase in CO2 ventilatory and CVRs after several days at high altitude has been suggested to occur because of the decline in cerebrospinal fluid HCO3−34, 35 which would result in larger pH reduction per mm Hg of PCO2 increase.11, 17 Despite this potential effect on the cerebrovascular tone, Lucas et al16 recently reported a reduced hypercapnic TCD CVR (measured in hyperoxia with a steady-state protocol) upon initial arrival and after 2 weeks at 5,050 m. One potential mechanism for reduced vasodilatory response to CO2 as in the present study and in Lucas et al16 may be the increased sympathetic nervous activity known to occur at altitude.36 The sympathetic control of cerebral perfusion remains,0 however, debated37 and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for changes in hypercapnic CVR at altitude.

The present study described, for the first time, alterations in NIRS signal in response to changes in arterial CO2 at altitude. Smielewski et al6 demonstrated that NIRS parameters react to alterations in arterial CO2, changes in HbO2 and HHb being significantly correlated to the change in TCD flow velocity measured nearby at the temporal window. The same authors showed the clinical value of NIRS responses to hypercapnia that were related to the severity of stenosis in patients with carotid artery diseases.38 In the present study, the TOI and HbO2 increase and the HHb reduction in response to hypercapnia were blunted at altitude. The correlation between TCD CVR and TOI responses at D5 suggest that reduced prefrontal oxygenation during CO2 inhalation may be due to a smaller increase in CBF. Hence, the NIRS data further suggest that the hypercapnic cerebral responses are altered after several days at high altitude as previously suggested.16, 23 We recently reported a reduced normoxic hypercapnic CVR measured by arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging at SL within a few hours after descent from several days at high altitude,23 showing that altitude-induced reduction in hypercapnic CVR observed in the present study does not depend on the hypoxic background during the measurement.

In addition to changes in peripheral chemosensitivity that are crucial for the development of ventilatory acclimatization as shown by changes in hypoxic ventilatory responses, changes in CO2 sensitivity is also relevant and can be potentially influenced by alteration in CVR. Hence, a reduction in CO2 CVR at altitude may enhance the CO2 ventilatory response by reducing cerebrospinal H+ washout while arterial CO2 increases.16 Changes in CO2 cerebral and ventilatory responses were, however, not correlated in the present study. A reduction in CO2 CVR may also promote breathing instability and the development of periodic breathing as frequently observed in newcomers to high altitude.13, 16 The reduction in cerebral oxygenation observed in the hypercapnic range at altitude might also suggest that the brain could be at risk of neurologic injuries during sleep apnea for instance.

As opposed to hypercapnic responses, we found no change in hypocapnic responses at high altitude. Cerebrovascular responses to CO2 are known to differ and possibly to involve distinct mechanisms in the hypercapnic and hypocapnic ranges.39 Previous studies have reported changes in TCD CVR to hypocapnia at high altitude.13, 16 These studies measured the hypocapnic TCD CVR while breathing ambient air at SL and at high altitude. It has been recently suggested40 that the comparison of hypocapnic reactivity may be influenced by the PaO2 increase associated with hyperventilation that could affect CBF differently when starting from normoxia (at SL) or preexisting hypoxia (at altitude). To eliminate this effect, we measured hypocapnic NIRS and TCD responses both at SL and at altitude while breathing a normoxic gas (leading to PetO2=100 mm Hg for 10 minutes before starting hyperventilation). The absence of change in NIRS and TCD responses to hypocapnia after several days at high altitude suggests that altitude-induced changes in CO2 CVR differ between the hypocapnic and hypercapnic range, the latter showing only significant alterations.

Finally, no correlation was observed between changes in hypoxic or CO2 cerebral responses and AMS severity. The present study was not designed to assess potential relationships between changes in cerebral perfusion and oxygenation and AMS severity, as only subjects with no AMS history (and therefore considered as AMS resistant) were included and because the demonstration of such a relationship would require a larger sample size.

Methodological Considerations

The hypercapnic responses were assessed under hypoxic conditions to mimic altitude conditions, i.e. to evaluate cerebral responses to CO2 as sojourners at high altitude would face while breathing ambient air. Because of the interaction between hypoxic and hypercapnic stimuli,22 the ventilatory and cerebrovascular hypercapnic responses measured in the present study may differ from measurements under normoxic or hyperoxic conditions.

Several limitations inherent to NIRS measurement should be noted. First, we measured cerebral oxygenation over the prefrontal cortex. Cerebral blood flow may be heterogeneously distributed under hypoxia41 and regional differences in cerebral oxygenation could not be detected within the present study. Second, although we sought to minimize the effects of near-surface blood flow by controlling room air temperature, by using a 4-cm inter-optode distance and by measuring the TOI provided by the NIRO-300 using NIR spatially resolved spectroscopy, we cannot rule out the possibility that superficial layers blood flow affected cerebral oxygenation measured by NIRS. Whether changes in blood gases affect skin blood flow similarly at SL and after several days at high altitude is unknown. Third, slight variations in probe placement could affect cerebral oxygenation measurements. To counteract this possibility, we carefully placed the probe holder at the same position on each experimental day.

The validity of TCD to measure variation in CBF depends critically on the assumption of a constant diameter of the investigated artery. Previous reports suggest that under the conditions of the present study (<5,000 m), MCA diameter remains constant,30, 42, 43 whereas at higher altitude, this may not be the case.43 Further studies with sensitive measurements of MCA diameter are, however, needed to confirm that absolute values and acute changes in MCAv as measured in the present study can be considered as a good estimate of absolute CBF and CBF responses at altitude. Because of the poor between-day reliability of standard TCD absolute MCAv assessment,44 we measured absolute MCAv under ambient air at SL and at altitude by using 2D transcranial color-coded sonography that enables precise identification of the M1 segment of the right MCA and insonation angle correction when determining blood flow velocities.25

Conclusion

The present study shows that changes in hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory and CVRs at high altitude are associated with significant alterations in prefrontal NIRS responses, cerebral oxygenation being less impaired in response to isocapnic hypoxia while reactivity of NIRS oxygenation variables to hypercapnia is smaller. The absence of change in hypocapnic responses suggests that the effect of altitude on cerebral responses to CO2 may differ between the hypercapnic and hypocapnic ranges. Based on correlations and kinetics of changes over the 5 days at altitude, ventilatory, TCD and NIRS responses appear to rely, at least in part, on distinct mechanisms. Further studies are needed to clarify their respective roles regarding altitude acclimatization.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the subjects for participating in this study, the SMTEC company for providing the gas mixing device, Philips, and Atys Medical for providing the TCD devices.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism website (http://www.nature.com/jcbfm)

We thank Rhône-Alpes Region for financial support.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hornbein TF. The high-altitude brain. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:3129–3132. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.18.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller K, Paulson OB, Hornbein TF, Colier WN, Paulson AS, Roach RC, et al. Unchanged cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism after acclimatization to high altitude. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus JW, Chiodi H, Eger EI, 2nd, Brandstater B, Hornbein TF. Cerebral blood flow in man at high altitude. Role of cerebrospinal fluid pH in normalization of flow in chronic hypocapnia. Circ Res. 1966;19:274–282. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JB, Wright AD, Lassen NA, Harvey TC, Winterborn MH, Raichle ME, et al. Cerebral blood flow in acute mountain sickness. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:430–433. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Ogoh S. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in mammals during chronic hypoxia: a matter of balance. Exp Physiol. 2009;95:251–262. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.045575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smielewski P, Kirkpatrick P, Minhas P, Pickard JD, Czosnyka M. Can cerebrovascular reactivity be measured with near-infrared spectroscopy. Stroke. 1995;26:2285–2292. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.12.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrey S. Non-invasive NIR spectroscopy of human brain function during exercise. Methods. 2008;45:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Barach A, Murrell C, Hamlin M, Hellemans J, Ogoh S. Alterations in cerebral autoregulation and cerebral blood flow velocity during acute hypoxia: rest and exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H976–H983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00639.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb JC, Ainslie PN, Ide K, Poulin MJ. Protocol to measure acute cerebrovascular and ventilatory responses to isocapnic hypoxia in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;141:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen JE, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH, DeLorey DS, duManoir GR, Petrella RJ, et al. Cerebral and muscle tissue oxygenation in acute hypoxic ventilatory response test. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;155:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JB, Sperling B, Severinghaus JW, Lassen NA. Augmented hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in men during 5 days at 3,810 m altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:1214–1218. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.4.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ, Fatemian M, Tansley JG, O'Connor DF, Robbins PA. Changes in cerebral blood flow during and after 48 h of both isocapnic and poikilocapnic hypoxia in humans. Exp Physiol. 2002;87:633–642. doi: 10.1113/eph8702437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Burgess K, Subedi P, Burgess KR. Alterations in cerebral dynamics at high altitude following partial acclimatization in humans: wakefulness and sleep. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:658–664. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00911.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Burgess KR. Cardiorespiratory and cerebrovascular responses to hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing: effects of acclimatization to high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;161:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GF, Krins A, Basnyat B. Cerebral vasomotor reactivity at high altitude in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:681–686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SJ, Burgess KR, Thomas KN, Donnelly J, Peebles KC, Lucas RA, et al. Alterations in cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity during 14 days at 5050 m. J Physiol. 2011;589:741–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JL, Burgess KR, Basnyat R, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJ, et al. Influence of high altitude on cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. J Physiol. 2010;588:539–549. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber AP, Hartley T, Pretorius PJ. Effect of acute exposure to 3660 m altitude on orthostatic responses and tolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:591–601. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00749.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terborg C, Gora F, Weiller C, Rother J. Reduced vasomotor reactivity in cerebral microangiopathy: a study with near-infrared spectroscopy and transcranial Doppler sonography. Stroke. 2000;31:924–929. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imray CH, Myers SD, Pattinson KT, Bradwell AR, Chan CW, Harris S, et al. Effect of exercise on cerebral perfusion in humans at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:699–706. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00973.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaggio A, Insalaco G, Marrone O, Romano S, Braghiroli A, Lanfranchi P, et al. Effects of high-altitude periodic breathing on sleep and arterial oxyhaemoglobin saturation. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:408–413. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Poulin MJ. Ventilatory, cerebrovascular, and cardiovascular interactions in acute hypoxia: regulation by carbon dioxide. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:149–159. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villien M, Bouzat P, Rupp T, Robach P, Lamalle L, Tropres I, et al. Changes in cerebral blood flow and vasoreactivity to CO(2) measured by Arterial Spin Labeling after 6 days at 4,350 m. Neuroimage. 2013;72:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ, Dahan A. The ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysis. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:675–754. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PJ, Evans DH, Naylor AR. Measurement of blood flow velocity in the basal cerebral circulation: advantages of transcranial color-coded sonography over conventional transcranial Doppler. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:21–26. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan A, Meek JH, Clemence M, Elwell CE, Fallon P, Tyszczuk L, et al. Measurement of cranial optical path length as a function of age using phase resolved near infrared spectroscopy. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:889–894. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199605000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach RC, Bartsch P, Hackett PH, Oelz O.The lake louise acute mountain sickness scoring systemIn: Sutton JR, Coates J, HC S eds. Hypoxia and Molecular Medicine Queen City Printers: Burlington, VT; 1993272–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JB, Cymerman A, Burse RL, Maher JT, Rock PB. Procedures for the measurement of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1983;54:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Severinghaus JW, Powell FL, Xu FD, Spellman MJ., Jr. Augmented hypoxic ventilatory response in men at altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:101–107. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb JC, Ainslie PN, Ide K, Poulin MJ. Effects of five consecutive nocturnal hypoxic exposures on the cerebrovascular responses to acute hypoxia and hypercapnia in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1745–1754. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00977.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow RM. The role of hemoglobin oxygen affinity in oxygen transport at high altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;158:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugniaux JV, Hodges AN, Hanly PJ, Poulin MJ. Cerebrovascular responses to altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;158:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZM, Krizay E, Guo J, Shin DD, Scadeng M, Dubowitz DJ. Sustained high-altitude hypoxia increases cerebral oxygen metabolism. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:11–18. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00703.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Forster HV, Gledhill N, doPico GA. Effects of moderate hypoxemia and hypocapnia on CSF [H+] and ventilation in man. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:665–674. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster HV, Dempsey JA, Chosy LW. Incomplete compensation of CSF [H+] in man during acclimatization to high altitude (48300 M) J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:1067–1072. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Lucas SJ, Fan JL, Thomas KN, Cotter JD, Tzeng YC, et al. Influence of sympathoexcitation at high altitude on cerebrovascular function and ventilatory control in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1058–1067. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00463.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Tzeng YC. On the regulation of the blood supply to the brain: old age concepts and new age ideas. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1447–1449. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00257.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Pickard JD, Kirkpatrick P. Clinical evaluation of near-infrared spectroscopy for testing cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with carotid artery disease. Stroke. 1997;28:331–338. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Eliasziw M, Poulin MJ. Relationship between middle cerebral artery blood velocity and end-tidal PCO2 in the hypocapnic-hypercapnic range in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:129–137. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01186.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller K. Every breath you take: acclimatisation at altitude. J Physiol. 2010;588:1811–1812. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.188615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Salmaso D, Sidiras G, Jonsson C, Jacobsson H, Larsson SA, et al. Impact of acute hypobaric hypoxia on blood flow distribution in brain. Acta Physiol. 2011;202:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ, Robbins PA. Indexes of flow and cross-sectional area of the middle cerebral artery using doppler ultrasound during hypoxia and hypercapnia in humans. Stroke. 1996;27:2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.12.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MH, Edsell ME, Davagnanam I, Hirani SP, Martin DS, Levett DZ, et al. Cerebral artery dilatation maintains cerebral oxygenation at extreme altitude and in acute hypoxia-an ultrasound and MRI study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2019–2029. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon CJ, McDermott P, Horsfall D, Selvarajah JR, King AT, Vail A. The reproducibility of transcranial Doppler middle cerebral artery velocity measurements: implications for clinical practice. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:21–27. doi: 10.1080/02688690701210539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.