Abstract

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins maintain the spatial expression patterns of genes that are involved in cell-fate specification along the anterior-posterior (A/P) axis. This repression requires cis-acting silencers, which are called PcG response elements (PREs). One of the PcG proteins, Pleiohomeotic (Pho), which has a zinc finger DNA binding protein, plays a critical role in recruiting other PcG proteins to bind to PREs. In this study, we characterized the effects of a pho mutation on embryonic segmentation. pho maternal mutant embryos showed various segmental defects including pair-rule gene mutant patterns. Our results indicated that engrailed and even-skipped genes were misexpressed in pho mutant embryos, which caused embryonic segment defects.

Keywords: eve, Drosophila melanogaster, GAGA, pleiohomeotic, Polycomb group genes, PRE, segmentation genes

INTRODUCTION

Segment identity along the anterior-posterior (A/P) axis is defined by the spatial expression patterns of homeotic genes in the Antennapedia complex (ANTC) and Bithorax complex (BXC) (McGinnis and Krumlauf, 1992). The spatial expression patterns of these complexes are maintained through interactions between Polycomb group (PcG) and trithorax group proteins (trxG) (Orlando and Paro, 1995; Pirrotta, 1998).

A major role of PcG proteins is to maintain the anteriorboundary of homeotic gene expression by repressing their expression in cells where their transcription has not been initiated (Pirrotta, 1998). Loss of function PcG mutations commonly cause ectopic homeotic expression and consequently a homeotic transformation, which is similar to the gain of function mutations in homeotic genes (Sinclair et al., 1992). However, derepression phenotypes vary widely among PcG mutations. Most PcG genes function maternally as well as zygotically (Breen and Duncan, 1986; Girton and Jeon, 1994).

PcG proteins function as part of Polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), including PRC1 (Francis et al., 2001), PRC2 (Francis et al., 2001; Saurin et al., 2001), and PhoRC complex. Of the molecularly characterized PcG proteins, only Pleiohomeotic (Pho) and its homolog, Pho-like (Phol), have been found to have DNA binding domains (Brown et al., 1998; 2003). Pho binds directly to PRC1 as well as to the Brahma (BRM) chromatin remodeling complex in Drosophila embryonic nuclear extracts (Mohd-Sarip et al., 2002). Pho also directly binds to a PRC2 in the wing imaginal disc (Wang et al., 2004). In addition, Pho interacts with drosophila Scm-related gene containing four mbt(dsfmbt) displaying methyl-lysine-binding activity when forming a Pho-repressive complex (PhoRC) (Klymenko et al., 2006), suggesting that Pho could be the initial recruiter of the PcG complex. The repression of gene expression by the PcG complexes occurs through Polycomb response elements (PREs) (Muller and Kassis, 2006). DNA sequences bound to Pho have been identified in a number of PREs of several genes and these sequences are required for silencing of gene expression (Brown et al., 1998; Fritsch et al., 1999; Mihaly et al., 1998). Moreover GAGA, which is encoded by the gene Trithorax- like (Trl) and colocalized with several PcG proteins at PREs, seems to facilitate Pho binding to chromatin (Mahmoudi et al., 2003; Strutt et al., 1997).

A large number of key developmental genes including the Hox genes have been shown to be Polycomb (Pc) targets (Kwong et al., 2008). Through whole-genome mapping to identify sites bound by the Pho, the majority of Pc targets were found to also be associated with Pho binding, indicating that Pho plays a widespread role in the maintenance machinery in cell fate determination. So far, over 200 PcG target genes have been identified (Brown et al., 1998; Kwong et al., 2008). These targets contain segmentation genes including en, eve, oddskipped (odd), Kruppel (Kr), wingless (wg), suggesting that PcG gene mutation may affect segmentation. Zygotic mutant embryos of Additional sex combs (Asx) and maternal effect mutant embryos of Polycomblike (Pcl) showed segment defects (Breen and Duncan, 1986; Sinclair et al., 1992).

Although Pho is molecularly well-characterized and expected to play an important role in the gene silencing process, its functions are still not fully understood. Here, we carefully characterized the effects of the pho maternal effect mutation on segmentation. Using various approaches to assess the effect of Pho, we argue that maternal Pho functions as a negative regulator of segmentation genes during early embryogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks and culture

The phocv allele was recovered as a recombinant from the phoc strain of Drosophila (Girton and Jeon, 1994). The phocv allele produced by the insertion of mdg4/gypsy elements (Brown et al., 2003) into the phocv allele. The mutation phocv / phocv is viable. Females produce embryos that die before hatching. Other mutations and balancers are described in Lindsley and Zimm (Lindsley and Zimm, 1992) and flybase (http://flybase. org). Flies were reared in 20 mm-diameter vials containing a standard cornmeal/yeast medium seeded with live yeast. Stocks were maintained at 20℃. Flies were reared at 25℃; eggs were also collected at 25℃.

Immunohistochemical and embryological studies

Immunohistochemical staining was performed with anti-En (4D9 from DSHB), anti-Eve (2B8 from DSHB) and anti-Kr (gift from Dr. Hiromi) primary antibodies and detected using a Vectastain ABC kit (Vectorlabs). RNA in situ hybridization on wholemounted embryos was performed using digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes, in accordance with Tautz and Pfeifle (Tautz and Pfeifle, 1989). For cuticle preparation, eggs were collected at 12 h intervals and further incubated for 24 h at 25℃.

Plasmids, antibodies, and reagents

Drosophila eve promoter DNA fragments containing from -667 to +174 were cloned into a pGL2-basic vector (Promega, USA) to yield pGL2-eve-Luc reporter plasmids. Drosophila GAGA cDNA and pho cDNA fragments were cloned into pPAC-PL to yield cloning pPAC-GAGA and pPAC-Pho, respectively. To prepare recombinant GST-fusion proteins, cDNA fragments encoding GAGA-ZFDBD and Pho-ZFDBD generated by PCR were cloned into pGEX4T3 (Amersham Biosciences, USA). All plasmid constructs were verified by sequencing.

GST fusion protein purification

To prepare bacterial-expressed recombinant fusion proteins, pGEX4T3-GAGA-ZFDBD and pGEX4T3-Pho-ZFDBD plasmids were transformed into E. coli (BL21-DE3). After culture and disruption of bacteria, soluble fractions of lysate were incubated with 2 ml GSH-agarose resin (Peptron, Korea) for 2 h at 4℃. After washing, bound proteins were eluted in 2 ml elution buffer (5 mM GSH, 50 mM Tris-HCl, final pH 8.0).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Oligonucleotide probes (500 picomoles each in 83.3 mM Tris- HCl, pH 8.0, 16.7 mM MgCl2, 166.7 mM NaCl) were annealed. 100 picomoles of annealed oligonucleotides for EMSAs were labeled with [α-32P]-ATP and Klenow enzyme (Roche, Germany). [α-32P]-labeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides were purified with SephadexTM G-50 (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden). Sequences of various oligonucleotide probes designed using well-known consensus binding sequences (Fritsch et al., 1999; Mihaly et al., 1998) used in EMSA are as follows (only the top strand is shown).

GAGA #1, 5′-GATCACACACTCTCTGCCG-3′; GAGA #2, 5′- GATCCGGAACTCTCTCTCTCTCCAGCT-3′; GAGA #3, 5′-GATCGCACCGAGAGCACAG-3′; GAGA #4, 5′-GATCATCCA CTCTCAGCAC-3′; GAGA #5, 5′-GATCTGGCTGAGAGCAG CA-3′. Pho #1, 5′-GATCGGGCGGCCATTATCT-3'; Pho #2, 5′- GATCAGGTTATGGCTGGAC-3′; Pho #3, 5′-GATCAAGTCA TGGCAGCCATGGCAGTGT-3′; Pho #4, 5′-GATCATAATGC CATATCAT-3′; Pho #5, 5′-GATCGGAGTGCCATGGCCAGC ATGGCCAGGAC-3′; Pho #6, 5′-GATCCGGCGGCCATTTGC C-3′.

Each binding reaction was performed in 20 μl binding buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 20 mM KCl, 0.8 mM EDTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 5 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1% BSA, 8% glycerol and purified recombinant GST-GAGAZFDBD (1 μg), GST-PhoZFDBD (1 μg). Protein-DNA complexes were resolved from free probes by 4% non-denaturing poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis at room temperature in 0.5× TBE buffer (89 mM Tris-Borate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.3).

Cell culture and transient transfection

Drosophila SL2 cells were transfected with 1 μg plasmid DNA using Cellfectin reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Cells were then harvested 24 h after transfection and lysed in 100 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega, USA). Luciferase activities were measured using the Luciferase Assay reagent (Promega, USA). Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity (Lee et al., 2011).

RESULTS

The pho maternal effect mutation affects the expression of engrailed

Pho was previously shown to bind to a PRE region of the en gene and mutation in pho released the pairing sensitive silencing generated by the engrailed fragment (Brown et al., 1998). This result suggested that pho might be involved in the regulation of segmentation. Therefore, we examined the expression of en in pho mutant embryos.

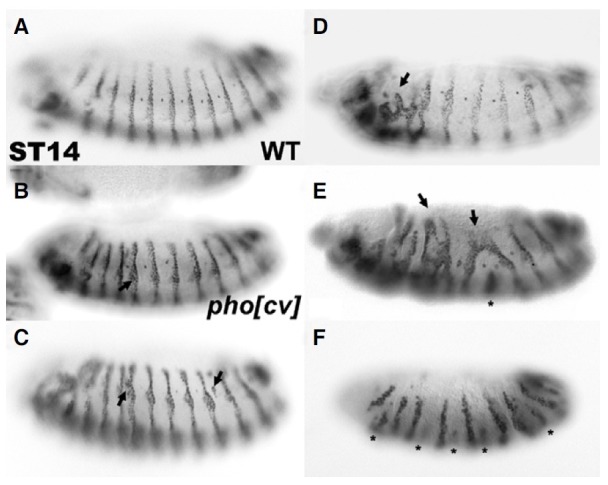

At stage 14 in wild type embryos, en was expressed in a series of 14 stripes approximately 1-2 cells wide (Fig. 1A). Midlaterally, a spur of en expression was extended in the anterior direction for 2-3 cells (DiNardo et al., 1985). When pho mutant embryos were analyzed on a larger scale, they frequently showed ectopic expression of en (41%, n = 39, Figs. 1B, 1C, arrows). This suggests that Pho is involved in maintaining the normal en expression pattern like other PcG proteins, such as Pc (Moazed and O’Farrell, 1992). In addition, en stripes frequently disappeared, were broken, or fused (Figs. 1D, 1E, Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, defects in en stripes often occurred alternatively along the thoracic and abdominal segments of embryos (Fig. 1F), suggesting that en stripe defects may be due to the abnormal expression of upstream segmentation genes caused by pho mutations.

Fig. 1. A pho mutation caused abnormal expression of eve. (A) At stage 14 in WT embryos, en was expressed in a series of 14 stripes approximately 1-2 cells wide and 2-3 cells mid-laterally. (BE) At stage 14, pho mutant embryos displayed different degrees of ectopic En expression (arrows). (D) The number of stripes was reduced, or (E-F) the stripes were reduced in pho mutant embryos (asterisk). Also in some pho mutants, stripes were broken (D) and fused with each other (E) or reduced like pair-rule mutants (F).

The pho maternal effect mutation causes segment-defects

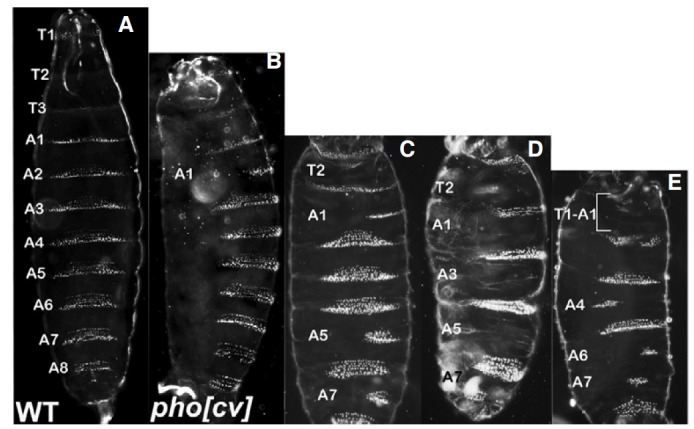

We previously reported that pho mutant embryos produced from phocv/phocv females displayed segment defects, suggesting that pho might be involved in segmentation (Breen and Duncan, 1986; Girton and Jeon, 1994; Kwon et al., 2003). To better understand the effects of pho on segmentation, we first carefully analyzed denticle defects in embryos from phocv /phocv females. Wild type embryos contained three fine thoracic denticle belts and eight abdominal ones (Fig. 2A). Denticle defects occurred in all segments with a high frequency in the second thoracic (T2) and odd-numbered abdominal segments (Figs. 2B-2E and Supplementary Table 2). More than 70% of pho mutant embryos showed segment defects in the T2, A1, and A7 segments, and quite a high percent of mutants (40 to 60%) displayed defects in the A3 and A5 segments. However, less than 10% of pho mutant embryos had defects in the A2, A4 and A8 abdominal segments. Such a high frequency of segment defects in pho mutant embryos has never been observed in other PcG mutant embryos.

Fig. 2. Embryonic denticle patterns. (A) WT first instar larva. The ventral cuticle pattern was characterized into three thoracic and eight abdominal denticle belts. (B-E) phocv /phocv maternal effect embryos. The pho mutants contained various segment defects. Labeled segments were partially or completely missing in denticle belts. The odd numbered abdominal segments were mostly affected.

phocv/phocv maternal effect mutation affects the expression of pair-rule genes

Frequent pair-rule pattern of denticle belt defects in pho mutant embryos (Supplementary Table 2) and abnormal en expression (Fig. 1) suggested that Pho might be involved in the regulation of segmentation genes at an earlier stage of the embryo. Therefore, we examined the expression of pair-rule genes.

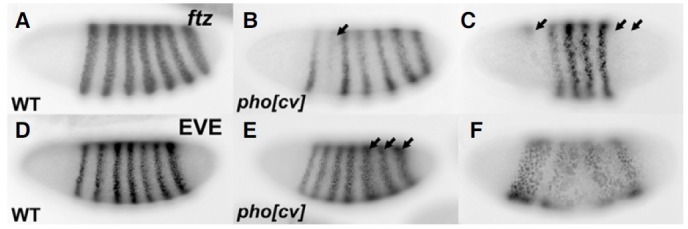

The odd-numbered segment defects in pho mutant embryos was similar to the mutant phenotypes of the pair-rule gene, fushi tarazu (ftz) (Weiner et al., 1984). So, we first examined the expression of ftz in pho mutant embryos. At the cellular blastoderm stage of wild type embryos, ftz is expressed in a sevenstripe pattern (Fig. 3A). In many pho mutant embryos, ftz stripes were partially missing (Figs. 3B and 3C, arrows), which might suggest that Pho could be a positive regulator of the ftz gene. However, this is in contrast to the general role of Pho as a negative regulator of genes. Furthermore, the ftz promoter of 1 kb upstream from the transcription start site has just a presumptive Pho binding site in a reverse direction. Thus, we speculated that the abnormal expression of the eve gene, a primary pairrule gene, might affect the expression of ftz, a secondary pairrule gene. The eve promoter has the presumptive nine Pho binding sites within 1 kb upstream from the transcription start site (Fritsch et al., 1999; Mihaly et al., 1998). According to a previous study, ectopic eve expression caused a loss of ftz expression (Manoukian and Krause, 1992).

Fig. 3. A pho maternal effect mutation did not maintain the expression of eve. At the cellular blastoderm stage in wild type embryos, ftz (A) and eve (D) were periodically expressed in even- and oddnumbered segments. Each stripe was 3-4 cells wide. In many pho maternal effect mutant embryos, ftz stripes were broken (B) or missing (C). In pho mutants, the expression of eve was extended (E) or the stripes were fused (F).

Eve is expressed in a seven-stripe pattern in wild type embryos (Fig. 3D), but in pho mutant embryos, their expressions were partially extended or even fused within each other’s stripe (Figs. 3E and 3F), suggesting that Pho negatively regulates eve expression. Although these phenotypes were quite variable, the expansion of eve stripes was mainly observed in the posterior region of the embryo (Fig. 3E). The interaction between Pho and eve was further verified in the ChIP assay in which eve was shown to have the predicted PREs (Kwong et al., 2008). In addition to the ChIP assay, eve was also shown to contain many PREs on its 5′ and 3′ locus and one of them was located near the promoter region, which might be involved in its maintenance during early embryogenesis (Fujioka et al., 2008). On the other hand, the PREs played no role in regulating the expression of ftz.

Pho acts as a negative regulator of eve interacting with GAGA

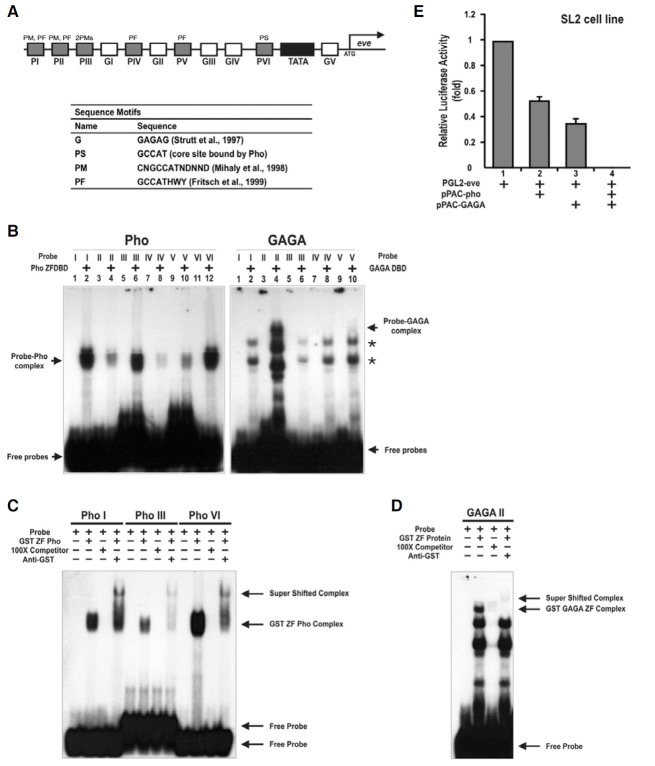

To further characterize eve-PREs, we first searched for predicted binding sites of Pho and GAGA in the 1 kb region of the promoter, which contained the TATA box, based on their wellconserved binding sequence, and found six and five potential binding sites of Pho and GAGA, respectively (Fig. 4A). One of the proteins involved in recruiting PcG proteins to the DNA may be a GAGA factor, which is a protein involved in nucleosome remodeling (Tsukiyama et al., 1994).

Fig. 4. Pho and GAGA bind to regulatory elements of the eve gene and potently repress its transcription. (A) Structure of the 1 kb regulatory region of the eve gene. Putative binding sites are indicated by the filled and open boxes. Open box, GAGA; filled gray box, Pho; filled black box, TATA box. Arrow, eve transcription starts. G is the GAGA consensus sequence (Strutt et al., 1997). P is the Pho consensus sequence (Fritsch et al., 1999; Mihaly et al., 1998). (B-D) DNA-Pho or GAGA interaction assays by EMSA. Pho binds to all six putative binding elements with varying degrees of affinity. The Pho-DNA complexes were supershifted by an antibody specific to the GST polypeptide. GAGA binds to only one site (GII) out of five putative sites tested, which was also supershifted by the antibody. Asterisks appear to be non-specific binding. (PhoI: -644 bp, PhoIII: -539 bp, GAGAII: -236 bp, PhoVI: +22 bp) (E) Transient transfection assays in Drospophila SL2 cells. Pho and GAGA strongly repressed the expression of a reporter luc gene by 50% and 65%, respectively. Co-transfection of Pho and GAGA expression vectors completely repressed luc transcription.

EMSA was performed to identify molecular events among Pho, GAGA, and their putative binding regulatory elements (Fig. 4). We also tried to determine which Pho binding sites were more important. Recombinant GST-PhoZFDBD bound to all potential binding sites with varying degrees of affinity (Fig. 4B). Particularly, Pho I, III and VI elements were strongly bound relatively to the others and were all supershifted when incubated with anti-GST after reacting with the recombinant protein (Fig. 4C). In contrast, GST-GAGAZFDBD bound to only one of its five predicted binding sites, the GAGA II element (GII), which were also supershifted under the same condition as the other Pho elements (Fig. 4D), suggesting that GII is a very important element in transcription repression by GAGA.

To investigate whether Pho represses the expression of eve through this regulatory region containing their potential binding sites in vitro, a luciferase activity assay in SL 2 cell was performed (Fig. 4E). In these experiments, Pho was shown to repress the transcription of the luciferase gene, which is a reporter gene, by 50% and GAGA repressed transcription by 65%. In addition, when Pho and GAGA were co-transfected, the reporter gene was almost completely repressed.

In summary, these results imply that Pho and GAGA repress the transcription of the eve gene by directly binding to the eve PRE element on its promoter, which may be important in maintaining the expression of eve during early embryonic segmentation.

DISCUSSION

Apart from homeotic transformations, one of the striking phenotypes produced by the phocv mutation is the appearance of embryonic segment defects. Segment defects were also observed in the mutant embryos of other PcG genes including Asx (Sinclair et al., 1992), Pcl (Breen and Duncan, 1986), and Sex comb extra (Sce) and Posterior sex comb (Psc) (Adler et al., 1991). These results imply that PcG proteins might be involved in regulating the expression of segmentation genes. However, the molecular mechanisms by which PcG proteins regulate segmentation genes have not been characterized yet.

It was shown that pho zygotic mutation caused a slight derepression of en (Moazed and O’Farrell, 1992). In fact, Pho was identified as a protein that binds to the PREs of the en gene and mediates pairing-sensitive silencing, suggesting that pho is involved in the regulation of en expression (Brown et al., 1998). Here, we showed that pho maternal mutation leads to relatively strong misexpression of en, indicating that maternal pho functions in maintaining the expression of en.

In addition to the ectopic expression of en, pho mutant embryos showed abnormal en stripe patterns including stripe fusion and stripe defects, mainly in even numbered stripes. These results are coincident with the predominant segment defects in the mesothorax and in the odd numbered abdominal segments. These findings strongly imply that these phenotypes are caused by alternations in the expression of the ftz gene, which might appear to be indirectly suppressed by ectopic expression of eve in pho mutation. In addition, Pho was shown to bind to the regulatory sites of eve in the EMSA and luciferase activity assay, which suggests that eve expression is regulated by maternal Pho. However, since some of the ftz stripes were missing, which was not exactly coincident with ectopic expression of eve stripes, segment defects may be caused by misregulation of other segmentation genes as well.

Maternal E(Z), which is a PcG, also acts to repress a gap gene, hb (Pelegri and Lehmann, 1994). In this study, we also found that some pho mutant embryos showed an expansion in the expression territory of Kr and kni to a more anterior domain (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2), which was shown to contain Pho binding sites in the ChIP assay (Kwong et al., 2008). These findings suggest that misexpressed Kr and kni in pho mutation might repress the expression of pair-rule genes. The ChIP assay also showed numerous other binding sites of Pho to segmentation genes including giant, odd-skipped, paired and wingless, etc (Kwong et al., 2008), which demonstrates that Pho may regulate other segmentation genes as well.

Taken together, various segment defects were due to derepression of multiple segmentation genes in pho mutant embryos, suggesting that Pho is involved in maintaining the expression pattern of segmentation genes as well as homeotic genes.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hiromi and Dr. Small for providing the anti-Kr, the anti-Kni and the ftz cDNA respectively. We also thank all the members of the Jeon’s and Hur’s laboratories for technical support. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (313-2008-2-C00727).

References

- 1.Adler P.N., Martin E.C., Charlton J., Jones K. Phenotypic consequences and genetic interactions of a null mutation in the Drosophila Posterior Sex Combs gene. Dev. Genet. (1991);12:349–361. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020120504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breen T.R., Duncan I.M. Maternal expression of genes that regulate the bithorax complex of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. (1986);118:442–456. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown J.L., Mucci D., Whiteley M., Dirksen M.L., Kassis J.A. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene pleiohomeotic encodes a DNA binding protein with homology to the transcription factor YY1. Mol. Cell. (1998);1:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J.L., Fritsch C., Mueller J., Kassis J.A. The Drosophila pho-like gene encodes a YY1-related DNA binding protein that is redundant with pleiohomeotic in homeotic gene silencing. Development. (2003);130:285–294. doi: 10.1242/dev.00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNardo S., Kuner J.M., Theis J., O’Farrell P.H. Development of embryonic pattern in D. melanogaster as revealed by accumulation of the nuclear engrailed protein. Cell. (1985);43:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis N.J., Saurin A.J., Shao Z., Kingston R.E. Reconstitution of a functional core polycomb repressive complex. Mol. Cell. (2001);8:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fritsch C., Brown J.L., Kassis J.A., Muller J. The DNA-binding polycomb group protein pleiohomeotic mediates silencing of a Drosophila homeotic gene. Development. (1999);126:3905–3913. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujioka M., Yusibova G.L., Zhou J., Jaynes J.B. The DNA-binding Polycomb-group protein Pleiohomeotic maintains both active and repressed transcriptional states through a single site. Development. (2008);135:4131–4139. doi: 10.1242/dev.024554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girton J.R., Jeon S.H. Novel embryonic and adult homeotic phenotypes are produced by pleiohomeotic mutations in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. (1994);161:393–407. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klymenko T., Papp B., Fischle W., Kocher T., Schelder M., Fritsch C., Wild B., Wilm M., Muller J. A Polycomb group protein complex with sequence-specific DNA-binding and selective methyl-lysine-binding activities. Genes Dev. (2006);20:1110–1122. doi: 10.1101/gad.377406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon S.H., Kim S.H., Chung H.M., Girton J.R., Jeon S.H. The Drosophila pleiohomeotic mutation enhances the Polycomblike and Polycomb mutant phenotypes during embryogenesis and in the adult. Int. J. Dev. Biol. (2003);47:389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwong C., Adryan B., Bell I., Meadows L., Russell S., Manak J. R., White R. Stability and dynamics of polycomb target sites in Drosophila development. PLoS Genet. (2008);4:e1000178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S., Kim S., Nahm M., Kim E., Kim T.I., Yoon J.H., Lee S. The phosphoinositide phosphatase Sac1 is required for midline axon guidance. Mol Cells. (2011) doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0168-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsley D.L., Zimm G.G. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press; (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahmoudi T., Zuijderduijn L.M., Mohd-Sarip A., Verrijzer C.P. GAGA facilitates binding of Pleiohomeotic to a chromatinized Polycomb response element. Nucleic Acids Res. (2003);31:4147–4156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manoukian A.S., Krause H.M. Concentration-dependent activities of the even-skipped protein in Drosophila embryos. Genes Dev. (1992);6:1740–1751. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGinnis W., Krumlauf R. Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell. (1992);68:283–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90471-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihaly J., Mishra R.K., Karch F. A conserved sequence motif in Polycomb-response elements. Mol. Cell. (1998);1:1065–1066. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moazed D., O’Farrell P.H. Maintenance of the engrailed expression pattern by Polycomb group genes in Drosophila. Development. (1992);116:805–810. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohd-Sarip A., Venturini F., Chalkley G.E., Verrijzer C.P. Pleiohomeotic can link polycomb to DNA and mediate transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. (2002);22:7473–7483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7473-7483.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller J., Kassis J.A. Polycomb response elements and targeting of Polycomb group proteins in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. (2006);16:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orlando V., Paro R. Chromatin multiprotein complexes involved in the maintenance of transcription patterns. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. (1995);5:174–179. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelegri F., Lehmann R. A role of polycomb group genes in the regulation of gap gene expression in Drosophila. Genetics. (1994);136:1341–1353. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirrotta V. Polycombing the genome: PcG, trxG, and chromatin silencing. Cell. (1998);93:333–336. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saurin A.J., Shao Z., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Kingston R.E. A Drosophila Polycomb group complex includes Zeste and dTAFII proteins. Nature. (2001);412:655–660. doi: 10.1038/35088096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinclair D.A., Campbell R.B., Nicholls F., Slade E., Brock H.W. Genetic analysis of the additional sex combs locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. (1992);130:817–825. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.4.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strutt H., Cavalli G., Paro R. Co-localization of Polycomb protein and GAGA factor on regulatory elements responsible for the maintenance of homeotic gene expression. EMBO J. (1997);16:3621–3632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tautz D., Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. (1989);98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukiyama T., Becker P.B., Wu C. ATP-dependent nucleosome disruption at a heat-shock promoter mediated by binding of GAGA transcription factor. Nature. (1994);367:525–532. doi: 10.1038/367525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L., Brown J.L., Cao R., Zhang Y., Kassis J.A., Jones R.S. Hierarchical recruitment of polycomb group silencing complexes. Mol. Cell. (2004);14:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner A.J., Scott M.P., Kaufman T.C. A molecular analysis of fushi tarazu, a gene in Drosophila melanogaster that encodes a product affecting embryonic segment number and cell fate. Cell. (1984);37:843–851. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]