Abstract

Cnu is a small 71-amino acid protein that complexes with H-NS and binds to a specific sequence in the replication origin of the E. coli chromosome. To understand the mechanism of interaction between Cnu and H-NS, we used bacterial genetics to select and analyze Cnu variants that cannot complex with H-NS. Out of 2,000 colonies, 40 Cnu variants were identified. Most variants (82.5%) had a single mutation, but a few variants (17.5%) had double amino acid changes. An in vitro assay was used to identify Cnu variants that were truly defective in H-NS binding. The changes in these defective variants occurred exclusively at charged amino acids (Asp, Glu, or Lys) on the surface of the protein. We propose that the attractive force that governs the Cnu-H-NS interaction is an ionic bond, unlike the hydrophobic interaction that is the major attractive force in most proteins.

Keywords: Cnu, DNA binding, H-NS, protein-protein interaction

INTRODUCTION

H-NS is a DNA-binding protein that represses gene expression. It appears that H-NS binds DNA in two steps (Rimsky et al., 2001). H-NS specifically binds to a high-affinity site, followed by the cooperative binding of additional H-NS molecules to lower-affinity sites (Bouffartigues et al., 2007). H-NS is a 15.6-kDa protein composed of 136 amino acids that presumably exists as a dimer in solution. H-NS has two structurally and functionally distinct domains (Badaut et al., 2002; Bloch et al., 2003; Dorman et al., 1999; Esposito et al., 2002; Renzoni et al., 2001; Shindo et al., 1995; 1999; Ueguchi et al., 1996; 1997), an N-terminal dimerization/oligomerization domain (residues 1 to 57 or 64) and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain (after residue 80). These two domains are separated by a long and flexible linker region. H-NS oligomerization is also important for the repression of gene expression (Rimsky et al., 2001).

There is a group of small 70-amino acid proteins that are required for H-NS function. These are Cnu and Hha in Escherichia coli (Kim et al., 2005; Nieto et al., 1991), RomA from the plasmid R100-1 (Nieto et al., 1998), and YmoA from Yersinia enterocolitica (Cornelis et al., 1991). The Cnu-H-NS complex binds to cnb (Kim et al., 2005), and the Hha-H-NS complex represses the hly operon that encodes the hemolysin toxin (Nieto et al., 2000). The YmoA-H-NS protein complex represses the inv gene in Y. enterocolitica (Ellison and Miller, 2006).

The Cnu protein, formerly identified as YdgT, was first described as a paralogue of Hha in E. coli (Paytubi et al., 2004). Cnu was originally identified as a DNA binding factor for a specific region in the origin of chromosomal DNA replication of E. coli (oriC), cnb (Kim et al., 2005) (Fig. 1B). The Cnu protein is composed of 71 amino acids and shares 38% identity and 68% related amino acids with Hha. Both proteins form functional protein complexes with H-NS in vivo. The arginine residue at position 12 (Arg12) in H-NS is involved in Hha binding (Garcia et al., 2006). A cysteine to isoleucine change at residue 18 (C18I) in Hha maintains H-NS binding activity, but abolishes the repression of the hly operon (Cordeiro et al., 2008). Recently, de Alba et al. (2011) identified the aspartic acid at position 48 (D48) of Hha as a key residue for H-NS binding. However, the physical interaction, structural integration, and attractive forces between Cnu and H-NS have not been studied.

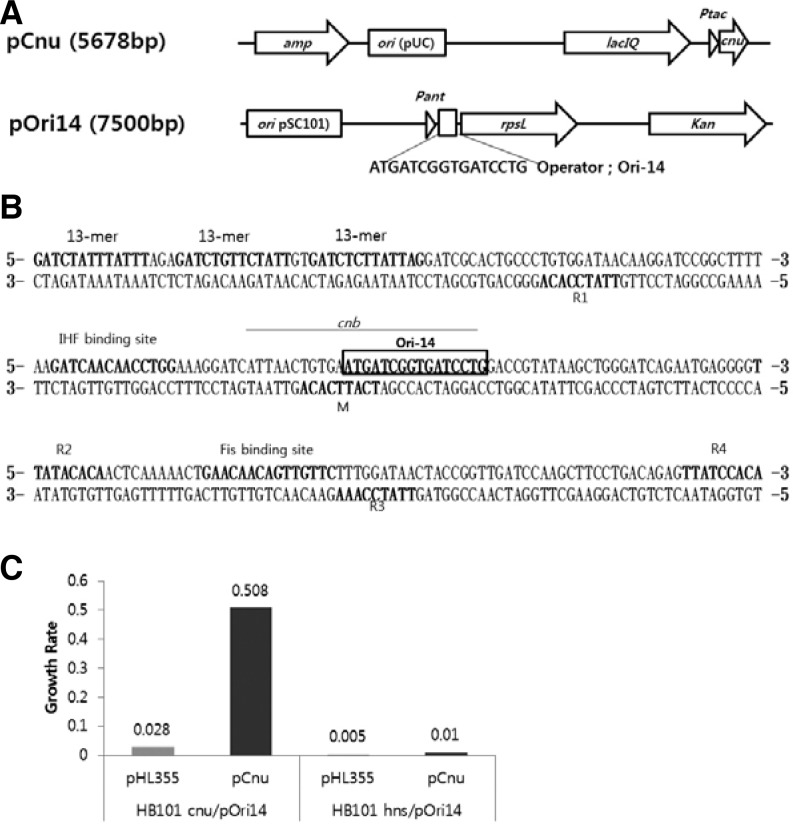

Fig. 1.

The plasmid map of pCnu and pOri14 (A). pCnu encodes the Cnu protein that binds as a Cnu-H-NS complex to the Ori-14 sequence in the operator region of pOri14. This binding activity makes the host cell (HB101) resistant to streptomycin. The DNA sequence of the oriC region in E. coli (B). The 13-mer regions are where DNA opening occurs during the initiation of chromosomal DNA replication. R and M regions are where DnaA protein binds. The Cnu-H-NS binding site (cnb) identified by (Kim et al., 2005) is overlined and the refined binding site (Ori-14 from this study) within cnb is boxed. The Growth Ratio (GR) of HB101 harboring the indicated plasmids are presented (C). Higher GRs correspond to better binding of the Cnu-H-NS complex to the Ori-14 sequence in vivo.

The purpose of this study was to examine the interaction between H-NS and Cnu at the molecular level. We randomly mutagenized the cnu gene and selected for mutants that did not interact with H-NS. Most of the selected Cnu variants had amino acid changes at charged residues on the surface of the protein (Asp, Glu, or Lys). We propose that the attractive force that governs the Cnu-H-NS interaction is an ionic bond, unlike the hydrophobic interactions that are the major attractive force used in most proteins (de Alba et al., 2011).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

E. coli strain HB101(F- mcrB mrr hsdS20(rB- mB-) recA13 leuB6 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 rpsL20(SmR) glnV44 λ-) was used throughout this study. BL21(DE3)/pLysS or BL21(DE3)hns/pLysS were used for the preparation of the His-tagged Cnu variants. The deletion of specific genes from these strains was performed by precisely removing the target gene following a previously published procedure (Yu et al., 2000).

Plasmid construction

The cnu gene was PCR-amplified using chromosomal DNA from HB101 as a template. A pair of primers having EcoRI or BamHI sites at the end was used for PCR amplification. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pHL355 (Kim et al., 2005) to make pCnu. Synthetic DNA fragments of Ori14-up (5′-ATGATCGGTGATCCTG-3′) and Ori14-down (5′-CAGGATCACCGATCAT-3′) were hybridized. The resulting double-stranded DNA fragment was cloned into the SmaI site of pHL343 (Kim et al., 2005) to make pHL562. The EcoRI-EcoRV restriction fragment of pHL204 (Lee et al., 1998) was replaced with the EcoRI-EcoRV restriction fragment of pHL562, completing the assembly of the substrate plasmid pOri14. To make His-tagged Cnu and the variants, the corresponding genes were PCR amplified and inserted into the NdeI-XhoI site of the plasmid pET15b (Novagen, Germany).

cnu random mutagenesis and screening for streptomycin-sensitive colonies

Random mutagenesis of cnu was performed using error-prone PCR (Joe et al., 2010). The cnu gene was amplified in a PCR reaction containing 10 ng plasmid pCnu, 0.5 μM of each primer (pHL355-RM-F primer, 5′-TTCACACAGGAAACAGAATTC-3′; pHL355-RM-B primer, 5′-CATCCGCCAAAACAGAAGCTT-3′), 5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Bioneer, Korea), dNTP mix (1 mM dCTP, 1 mM dTTP, 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dGTP, final concentration), and 1X error-prone PCR buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 50 mM KCl, 7 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% gelatin (W/V)] under the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 30 s at 72°C. PCR products were purified using a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) and ligated into EcoRI/BamH1-digested pHL355. The ligation was performed overnight at 25°C and the ligation products were introduced into HB101cnu/pOri14 by electroporation (BioRad). The transformed cells were plated on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The next morning, transformants were individually transferred simultaneously on LB agar plates containing ampicillin, kanamycin, streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 20 μM IPTG, and on to similar LB agar plates lacking streptomycin. Plates were incubated at 37°C. More than 2000 colonies were screened and 89 Str-sensitive colonies were identified. The pCnu plasmid was isolated from the Str-sensitive colonies and mutations were identified by DNA sequencing of the cnu gene in pCnu (Solgent, Korea).

Measurement of growth ratio

The overnight culture of HB101cnu harboring pOri-14 and each mutant cnu encoding plasmid grown at 37°C in LB with proper antibiotics was diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in LB with proper antibiotics and IPTG. For the GR measurement, the OD600 was measured every 2 h.

Purification of 6xHis-Cnu mutants

BL21(DE3)/pLysS carrying pET-Cnu or pET-Cnu-mutants were grown to OD600 of 0.6 at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm in 50 ml LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (Cm; 22 μg/ml). For induction of the target gene, IPTG was added (0.2 mM final concentration) and cells were grown at 15°C for Cnu or Cnu-mutants for an additional 16 h with 200 rpm shaking. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 570 μl Binding & Wash buffer (Tris-HCl, pH8.0, and 100 mM NaCl) and 30 μl of 5 M NaCl. Cells were opened by sonication (power 45%, 2 s, 1-s pause for 1 min, 30-s interval, three times, SoNo-Plus, Bandelin, Germany). Target proteins were purified using MagExtractor-His-tag® magnetic beads (Toyobo, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. To the 600 μl of the supernatants, 40 μl of magnetic beads (MagaExtractor-His-tag, Toyobo, Japan) were added and mixed using a rotator at room temperature for 30 min. The magnetic beads were washed twice with 500 μl Binding & Wash buffer and resuspended in 150 μl Elution buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 200 mM imidazole). Proteins were eluted using a rotator at 25°C for 10 min. An equal volume of 100% glycerol was added to the supernatant (150 μl) and mixed. Proteins were kept at −20°C.

RESULTS

DNA binding activity of the Cnu-H-NS complex to Ori-14 sequence

The DNA binding activity of the Cnu-H-NS complex can be measured using an in vivo assay system based on bacterial genetics, in which Cnu-H-NS binding to an operator DNA sequence results in the repression of the rpsL gene on a low-copy plasmid, pOri14 (Fig. 1A). In an E. coli strain such as HB101 that harbors pOri14, the DNA binding activity of the Cnu-H-NS complex to the operator confers resistance to the antibiotic streptomycin (Str). Previously, we measured the growth rate of HB101 cells in Str-containing LB medium to assay the DNA binding activity of the Cnu-H-NS complex and found a direct relationship between the binding activity of the Cnu-H-NS complex to the operator sequence and the growth rate of host cells in Str-medium (Kim et al., 2005).

In a series of experiments using the in vivo assay system described above, we identified a specific 16-base pair DNA sequence in the oriC, the origin of chromosomal DNA replication of E. coli (Fig. 1B), whose presence as the operator sequence in pOri14 can allow the host cells to grow in Str-medium. The growth rate of HB101 harboring both pOri14 and pCnu (HB101/pOri14/pCnu) in Str-LB medium was about half (0.5) of the growth rate of the same cells in LB-medium. pCnu is a high copy number plasmid in which the cnu gene is expressed under the control of the promoter tac (Ptac, Fig. 1A). The growth rate in Str-LB compared to that in LB was defined as the growth ratio (GR) (Fig. 1C). The GR of HB101cnu/pOri14/pCnu reached 0.5 only when the cnu gene was induced with isopropyl-beta-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). HB101cnu is a strain of HB101 in which the cnu gene is removed. However, when IPTG was not added to the medium or when pHL355 (pCnu without the cnu gene) was used instead of pCnu, the GR of HB101cnu/pOri14 fell below 0.03, suggesting that Cnu is indeed a critical factor in binding to the Ori-14 sequence. Interestingly, when the hns gene was removed from HB101 (HB101hns), t he GR o f HB101hns/pOri14/pCnu decreased to 0.01, indicating that the host cells had become Str-sensitive. These results suggest that H-NS plays a critical role in the binding of the Cnu-H-NS complex to the Ori-14 sequence. The results also suggest that H-NS alone does not bind to the Ori-14 sequence, but that H-NS must form the Cnu-H-NS complex to efficiently bind to the Ori-14 sequence.

Searching for Cnu-variants that cannot make protein contacts with H-NS

The observation that the GR of HB101cnu/pOri14/pCnu when Cnu is induced is 0.5 indicates that this strain can form a colony in Str-LB medium. Because the loss of either Cnu or H-NS from this strain lowered the GR of the cells to the point that they could not form a colony in Str-LB, we were able to screen for mutant Cnu-proteins that had lost the ability to make protein-protein interactions with H-NS.

We randomly mutagenized the cnu gene in pCnu and transformed HB101cnu/pOri-14. Transformants were plated on LB agar plates and individually-transferred onto Str-LB plates the following day to screen for colonies that could not grow on Str-LB. We screened 2,000 transformants and found 89 Str-sensitive colonies. DNA sequencing of the variant cnu genes in pOri14 isolated from the 89 Str-sensitive colonies identified 40 cnu mutants (Table 1). Most variants (82.5%) had a single amino acid change, but a few variants (17.5%) had double changes.

Table 1.

Amino acid changes in the Cnu variants

| Structure | N-term | Helix1 | Loop1 | Helix2 | Loop2 | Helix3 | C-term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Residue no. | 1–5 | 6–13 | 14–18 | 19–28 | 29–33 | 34–52 | 53–71 |

| Single amino acid Change | Q4R | K9R | S15P | E20G | T29P | M39K | Q61R |

| F10I | E17V | K21E | D32V | M39R | V62E | ||

| K21I | M39Y | V66D | |||||

| Y23H | M39T | W67R | |||||

| D24V | D44N | Y69F | |||||

| L26P | D44V | V70G | |||||

| L26H | D44E | Q71H | |||||

| H45L | |||||||

| E49G | |||||||

| E49V | |||||||

| L50P | |||||||

| V51D | |||||||

| Double amino acid change | K12E | L22V | |||||

| L26H | M39I | ||||||

| Y23H | Q61R | ||||||

| D24V | D58V | ||||||

| D32V | V62A | ||||||

| K21E/Y28H | |||||||

| H68L/V70G | |||||||

Cnu variants that could not make protein contacts with H-NS

The structure of Cnu revealed by a NMR study showed that Cnu is composed of three alpha helices with two turns between the helices. The five amino acid residues at the N-terminus and 18 amino acids at the C-terminus are not structured (Bae et al., 2008). The amino acid changes in our Cnu variants are listed according to their position in the helices and turns (Table 1).

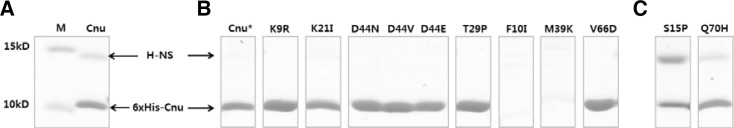

We conducted an in vitro assay to confirm that the Cnu variants are indeed unable to form complexes with H-NS. The crude protein preparation containing His-tagged Cnu was loaded onto a nickel affinity column, and the His-tagged Cnu protein was co-eluted with H-NS from the column (Fig. 2A) (Kim et al., 2005), suggesting that the Cnu-H-NS complex maintained close contact during the in vitro procedures. We then assayed the ability of Cnu variants to form protein complexes with H-NS. We overexpressed His-tagged variant Cnu proteins and bound them to a nickel affinity column. When the majority of Cnu variants were eluted from the nickel column, H-NS protein was not co-eluted (Fig. 2B), suggesting that those Cnu variants could not form a Cnu-H-NS complex. These in vitro results support the in vivo results of the screen. Two variants, F10I (phenylalanine at position 10 changed to isoleucine) and M39K were barely detectable in the soluble fraction when stained with Coomassie Blue (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, these tagged variants were detected in the insoluble fraction indicating that these proteins were largely insoluble (data not shown). It is likely that F10I and M39K make the Cnu protein insoluble due to the location and chemical nature of the changed amino acids (see below). However, H-NS did co-elute with the S15P and Q70H variants (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the S15P and Q70H variants in the protein complex likely prevent H-NS from binding to the Ori-14 sequence.

Fig. 2.

Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide protein gels indicate that H-NS is co-eluted with the His-tagged Cnu from the nickel affinity column (A). The same protein gels from some of the Cnu variants (B) showing that H-NS is not co-eluted with the corresponding Cnu variant. F10I and M39C Cnu variants are not detected in the protein gel. Some variants, such as S15P and Q70H, are co-eluted with H-NS (C). Cnu* shows that H-NS is not co-eluted when the His-tagged Cnu is prepared from hns-deleted BL21(DE3). M indicates a protein molecular marker. Nine micrograms of protein were loaded in each lane.

Location and chemical nature of the mutated amino acid residues

The Cnu variants were divided into four groups (internal, external, loop, and C-terminal) based on the location of the changes (Table 2). Interestingly, changes grouped by the location share the same chemical nature of the original amino acid: the original amino acids of the variants of the internal group are all hydrophobic, and those of the external group are all charged (Table 2).

Table 2.

Original amino acid of the Cnu variants

| Group | Internal | External | Loop | C term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phe10 | Lys9 | Gln4 | Gln61 | |

| Leu22 | Glu20 | Ser15 | Val62 | |

| Tyr23 | Lys21 | Glu17 | Val66 | |

| Leu26 | Asp24 | Thr29 | Trp67 | |

| Met39 | Asp44 | Asp32 | Tyr69 | |

| Leu50 | Glu49 | Val70 | ||

| Gln71 |

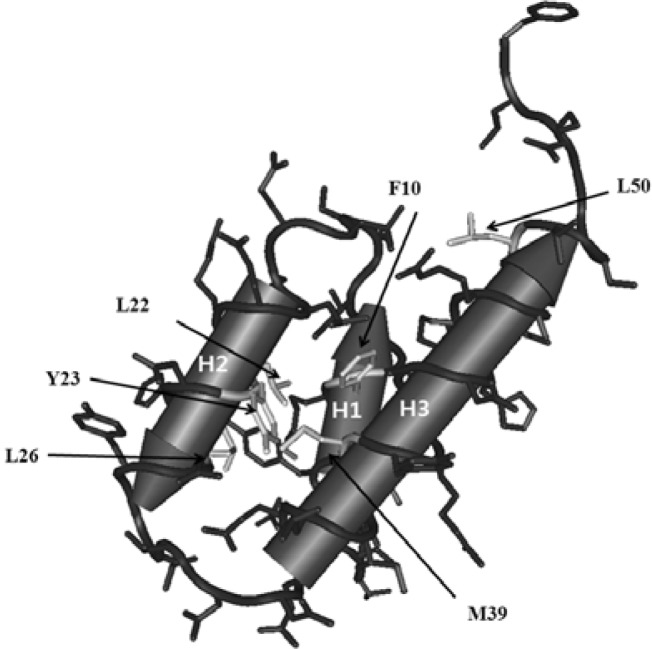

Internal

Variants in this group have changes at the interior of the protein. The variants belonging to this group are: F10I, L22V, Y23H, L26P, L26H, M39K, M39R, M39Y, M39T, and L50P. There were four independent changes at Met39. The wild-type amino acids of these variants are Phe, Leu, and Met, which are all hydrophobic. The 3D structure of Cnu indicates that Phe 10 resides in helix 1, while Leu 22 and Tyr 23 are located in helix 2, and Met 39 resides in helix 3 (Fig. 3). Close examination of residue positions in the 3D structure of Cnu revealed that the side-chains are within 3-Å proximity (Fig. 3). It is likely that the close proximity of these hydrophobic side chains establish a hydrophobic interaction that stabilizes the three alpha helices. The insoluble nature of F10I and M39K may have resulted from destabilization of the hydrophobic interaction due to the bulky replacement of Ile for Phe at residue 10 and the charge incorporation by Lys at residue 39, respectively.

Fig. 3.

A schematic presentation of the side chains of the Cnu variants belonging to the internal group. The corresponding side chains are shown in white. Alpha helices (H1, H2, and H3) are indicated by a cylinder with arrow head that indicates the direction of the C-terminus. This 3D structure of Cnu was drawn using Cn3D (Wang et al., 2000) based on Protein data bank ID 2JQT.

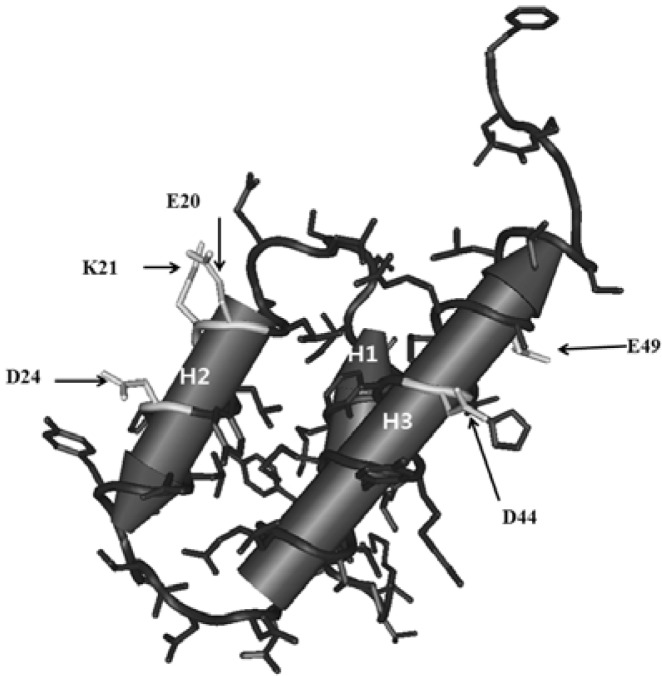

External

Variants in this group have changes at the external surface of the protein. The variants belonging to this group are: E20G, K21E, K21I, D24V, D44N, D44V, D44E, E49G, and E49V. There were two and three independent changes at Lys21 and Asp44, respectively. It is interesting that the wild-type amino acids of these variants are Lys, Glu, and Asp, which are all polar and charged residues. The 3D structure of Cnu indicates that residues Glu 20, Lys 21, and Asp 24 lie in helix 2. Asp 32 is a part of loop 2 and Asp 44 and Glu 49 lie in helix 3 (Fig. 4). The interaction between Cnu and H-NS seems to be specific and subtle because the change of Asp 44 to Glu in the D44E variant abolished the interaction, even though both residues contain similar carboxylic groups that differ only in that Asp lacks one methylene group.

Fig. 4.

A schematic presentation of the side chains of the Cnu variants belonging to the external group. The corresponding side chains are shown in white.

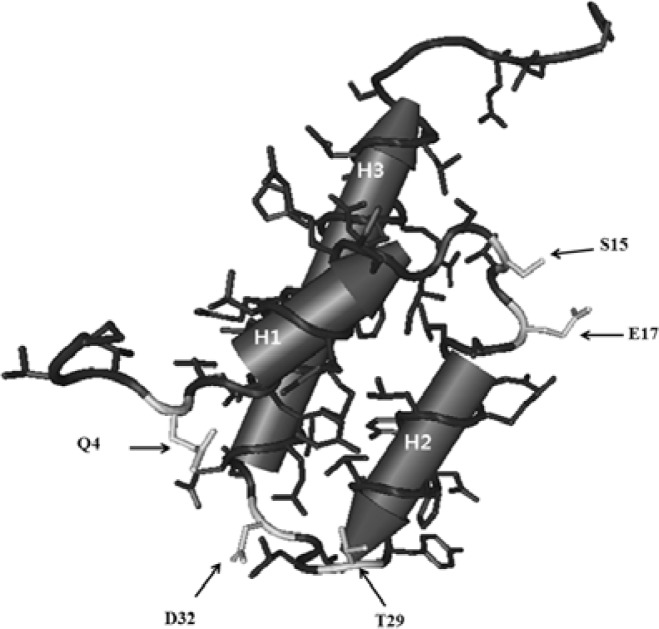

Loop

Variants in this group have changes in the loops of the Cnu protein. The variants belonging to this group are: Q14R, S15P, E17V (loop1), T29P, and D32V (loop2) (Fig. 5). No clear patterns of original or changed amino acid characteristics were found.

Fig. 5.

A schematic presentation of the side chains of the Cnu variants belonging to the loop group. The corresponding side chains are shown in white.

Unstructured C-terminal

The variants in this group have amino acid changes at the unstructured C-terminal portion of Cnu (residues 53–71). The changes were clustered toward the end of the protein (residues 60–71). No clear patterns of original or changed amino acid characteristics were found.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used an in vivo binding assay for Cnu and H-NS to the Ori-14 sequence and found that the binding of Cnu protein to the Ori-14 sequence required H-NS and vice versa, suggesting that Cnu and H-NS bind to the Ori-14 sequence as a Cnu-H-NS complex. Furthermore, we identified amino acid residues that are critical for this Cnu-H-NA complex. H-NS is a known DNA-binding protein (Dorman, 2004 and references therein). Amino acid comparisons of Cnu and H-NS indicate that Cnu lacks a DNA binding motif (Fang and Rimsky, 2008). Thus, it is hypothesized that the role of Cnu is to modulate the DNA-binding activity of H-NS, enabling H-NS to bind to a specific sequence of DNA. We found that the S15P and Q70H variants formed a protein complex with H-NS, but the growth rate of HB101/pOri14 harboring these variants in Str-LB was 0.005, suggesting that S15P-H-NS and Q70H-H-NS complexes are not able to bind to the Ori-14 sequence. These results further support our hypothesis that Cnu modulates the DNA-binding activity of H-NS. Since the molar ratio of the Cnu-H-NS complex is 2:1 (Bae et al., 2008), it is possible that the binding of a Cnu monomer to an H-NS dimer allows H-NS to bind to a specific sequence of DNA.

The Internal group of the Cnu variants may have been identified in our screen because of their altered structures leading to insoluble proteins. The importance of these hydrophobic residues in stabilizing the three alpha helices was suggested by a NMR study of Cnu (Bae et al., 2008). Therefore, it is likely that these variants are not defective in specific interactions with H-NS, but in their proper folding. However, some of these variants, such as S15P or Q70H, might be defective in Ori-14 binding rather than in the interaction with H-NS because they co-eluted with H-NS from the nickel affinity column. Most of the variants belonging to the External group appear to be true interaction-defects; they were not co-eluted with H-NS from the nickel column and they were soluble (data not shown). The original amino acids of the external group were all charged residues: Asp, Glu, and Lys. These data suggest that the interaction energy between Cnu and H-NS comes from ionic interactions rather than hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, or Van der Waals forces. de Alba et al. (2011) have reported that the key residue of Hha in binding H-NS is Asp48 (equivalent to Asp44 in Cnu) strongly supports this idea. Thus, it is possible that changes in ionic strength or pH in the cell modulate the interaction between Cnu and H-NS by changing the charges across the surface of Cnu.

Our results from a mutagenic screen using an in vivo assay to detect the binding of Cnu and H-NS to the Ori-14 sequence suggest that the interaction between Cnu and H-NS largely depends on ionic bonds. Additionally, this interaction is essential for the DNA-binding activity of H-NS. Based on our results, we hypothesize that cellular pH changes the DNA-binding activity of H-NS by altering the interaction between Cnu and H-NS. If this is the case, our study may provide the mechanistic basis for how the initiation of DNA replication can be induced by a change in cellular pH. Analysis of the Cnu-H-NS DNA-binding activity at various pH levels is currently in progress.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank a Biology undergraduate Park, Dongnyuk for his work on the cnu random mutagenesis. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2011-0004864). This work was also supported by the 21C Frontier Microbial Genomics and Application Center Program (MG08-0201-2-0).

REFERENCES

- Badaut C., Williams R., Arluison V., Bouffartigues E., Robert B., Buc H., Rimsky S. The degree of oligomerization of the H-NS nucleoid structuring protein is related to specific binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41657–41666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S.H., Liu D., Lim H.M., Lee Y., Choi B.S. Structure of the nucleoid-associated protein Cnu reveals common binding sites for H-NS in Cnu and Hha. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1993–2001. doi: 10.1021/bi701914t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch V., Yang Y., Margeat E., Chavanieu A., Auge M.T., Robert B., Arold S., Rimsky S., Kochoyan M. The H-NS dimerization domain defines a new fold contributing to DNA recognition. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:212–218. doi: 10.1038/nsb904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffartigues E., Buckle M., Badaut C., Travers A., Rimsky S. H-NS cooperative binding to high-affinity sites in a regulatory element results in transcriptional silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:441–448. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro T.N., Garcia J., Pons J.I., Aznar S., Juarez A., Pons M. A single residue mutation in Hha preserving structure and binding to H-NS results in loss of H-NS mediated gene repression properties. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3139–3144. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G.R., Sluiters C., Delor I., Geib D., Kaniga K., Lambert de Rouvroit C., Sory M.P., Vanooteghem J.C., Michiels T. ymoA, a Yersinia enterocolitica chromosomal gene modulating the expression of virulence functions. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba C.F., Solorzano C., Paytubi S., Madrid C., Juarez A., Garcia J., Pons M. Essential residues in the H-NS binding site of Hha, a co-regulator of horizontally acquired genes in Enterobacteria. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1765–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C.J. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C.J., Hinton J.C., Free A. Domain organization and oligomerization among H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison D.W., Miller V.L. H-NS represses inv transcription in Yersinia enterocolitica through competition with RovA and interaction with YmoA. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5101–5112. doi: 10.1128/JB.00862-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D., Petrovic A., Harris R., Ono S., Eccleston J.F., Mbabaali A., Haq I., Higgins C.F., Hinton J.C., Driscoll P.C., et al. H-NS oligomerization domain structure reveals the mechanism for high order self-association of the intact protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F.C., Rimsky S. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J., Madrid C., Juarez A., Pons M. New roles for key residues in helices H1 and H2 of the Escherichia coli H-NS N-terminal domain: H-NS dimer stabilization and Hha binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe E.J., Kim B.G., An B.C., Chong Y., Ahn J.H. Engineering of flavonoid O-methyltransferase for a novel regio-selectivity. Mol Cells. 2010;30:137–141. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Bae S.H., Yun S.H., Lee H.J., Ji S.C., Lee J.H., Srivastava P., Lee S.H., Chae H., Lee Y., et al. Cnu, a novel oriC-binding protein of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6998–7008. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.6998-7008.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.Y., Lee H.J., Lee H., Kim S., Cho E.H., Lim H.M. In vivo assay of protein-protein interactions in Hin-mediated DNA inversion. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:5954–5960. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5954-5960.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto J.M., Carmona M., Bolland S., Jubete Y., de la Cruz F., Juarez A. The hha gene modulates haemolysin expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:1285–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto J.M., Prenafeta A., Miquelay E., Torrades S., Juarez A. Sequence, identification and effect on conjugation of the rmoA gene of plasmid R100-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998;169:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto J.M., Madrid C., Prenafeta A., Miquelay E., Balsalobre C., Carrascal M., Juarez A. Expression of the hemolysin operon in Escherichia coli is modulated by a nucleoid-protein complex that includes the proteins Hha and H-NS. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;263:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s004380051178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paytubi S., Madrid C., Forns N., Nieto J.M., Balsalobre C., Uhlin B.E., Juarez A. YdgT, the Hha paralogue in Escherichia coli, forms heteromeric complexes with H-NS and StpA. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:251–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzoni D., Esposito D., Pfuhl M., Hinton J.C., Higgins C.F., Driscoll P.C., Ladbury J.E. Structural characterization of the N-terminal oligomerization domain of the bacterial chromatin-structuring protein, H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:1127–1137. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsky S., Zuber F., Buckle M., Buc H. A molecular mechanism for the repression of transcription by the H-NS protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:1311–1323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo H., Iwaki T., Ieda R., Kurumizaka H., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T., Morikawa S., Nakamura H., Kuboniwa H. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of a nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS, from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00079-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo H., Ohnuki A., Ginba H., Katoh E., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T., Yamazaki T. Identification of the DNA binding surface of H-NS protein from Escherichia coli by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00862-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi C., Suzuki T., Yoshida T., Tanaka K., Mizuno T. Systematic mutational analysis revealing the functional domain organization of Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:149–162. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi C., Seto C., Suzuki T., Mizuno T. Clarification of the dimerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;274:145–151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Geer L.Y., Chappey C., Kans J.A., Bryant S.H. Cn3D: sequence and structure views for Entrez. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:300–302. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Ellis H.M., Lee E.C., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G., Court D.L. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2000;97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]