Abstract

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) is a plant bacterial pathogen that causes bacterial blight (BB) disease, resulting in serious production losses of rice. The crystal structure of malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (XoMCAT), encoded by the gene fabD (Xoo0880) from Xoo, was determined at 2.3 Å resolution in complex with N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethansulfonic acid. Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase transfers malonyl group from malonyl CoA to acyl carrier protein (ACP). The transacylation step is essential in fatty acid synthesis. Based on the rationale, XoMCAT has been considered as a target for antibacterial agents against BB. Protein-protein interaction between XoMCAT and ACP was also extensively investigated using computational docking, and the proposed model revealed that ACP bound to the cleft between two XoMCAT subdomains.

Keywords: acyl carrier protein, computational docking, fatty acid synthesis, malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase, Xanthomanous oryzae pv. oryzae

INTRODUCTION

Rice is one of the most common food staples throughout the world. Bacterial blight (BB) is a serious and destructive disease causing massive production losses of rice. BB is caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) (Ezuka A, 2000), which is prevalent in tropical countries, particularly in Asia. However, no effective drugs against BB have been identified until now. Lee and coworkers reported the whole genomic sequence of Xoo (Lee et al., 2005), which has provided useful information for the selection of essential drug target enzymes from its 4538 putative genes. Xoo0880 (XoMCAT) is one of the target genes, which is related to the fatty acid synthesis (FAS) in bacteria (Payne et al., 2004; 2007; Yoon et al., 2011).

Biosynthesis of fatty acids is essential for all living organisms (Magnuson et al., 1993; White et al., 2005). The type I FAS system found in animals consists of a single polypeptide chain made up of eight distinct domains that is involved in all catalytic reactions. In contrast, bacteria have the type II FAS system, which involves a series of individual enzymes. Xoo0880 expresses malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (MCAT, EC2.3.1.39), which is responsible for transferring a malonyl group to acyl carrier protein (ACP). Resulting malonyl-ACP intermediate participates in type II FAS (Ruch and Vagelos, 1973). Thus MCAT takes part in FAS by extending the length of the growing chain by two carbon atoms via providing malonyl-ACP as a two carbon donor in the elongation step of FAS. MCAT also provides acyl-ACP thioesters, which are related with aromatic polyketide biosynthesis and secondary metabolites such as tetracyclines and erythromycins (Keatinge-Clay et al., 2003; Summers et al., 1995). MCAT has been considered as a target for antibacterial agents (Campbell and Cronan, 2001; Miesel et al., 2003), and our group selected XoMCAT as a potential drug target against BB. In this study, we determined the crystal structure of XoMCAT in complex with N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethansulfonic acid (NHE) at the active site. To understand its interaction with ACP, protein-protein (P-P) docking of XoMCAT and ACP was carried out. The determined XoMCAT structure could be useful in developing antibacterial agents against BB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression and purification of XoMCAT

The strain of Xoo KACC10331 was obtained from the Rural Development of Administration (RDA), South Korea. The E. coli host strain BL21 (DE3) was purchased from Novagen. Cloning, expression, and purification of XoMCAT were performed as described in the previous report (Jung et al., 2008). The purity of the enzyme was examined by SDS-PAGE analysis, and the protein concentration (7 mg ml−1) was determined by Bradford (1976).

Crystallization and data collection

Well-diffracted XoMCAT crystal was grown at 283K under the condition of 0.1 M CHES pH 9.0, 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and 0.2 M NaCl by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method in a week. Before collecting data, a crystal was frozen in liquid nitrogen with 25% (v/v) glycerol as a cryoprotectant. The entire data were collected at 2.3Å resolution using an ADSC quantum 270 CCD detector of the beam-line 17A at the photon factory (KEK), Japan. The data set was integrated and scaled using the DENZO and SCALEPACK programs (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997), respectively. All relevant crystallographic parameters and refinement details are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystal parameters and refinement statistics

| Crystal data parameters | XoMACT/NHE |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell constant (Å) | |

| a | 41.4 |

| b | 74.6 |

| c | 98.5 |

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | PF-17A |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.96418 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0−2.3 |

| No. reflections | 61,832 |

| No. unique reflections | 12,427 |

| Completeness (%) | 92.2 (88.2) |

| Average I/σ (I) | 30.9 (3.7) |

| †Rmerge (%) | 6.0 (33.0) |

| Redundancy | 5.0 |

| Refinement | |

| Refmac5 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 49.3−2.3 |

| No. protein atoms | 2293 |

| No. of water | 159 |

| No. of ligand | 1 (NHE) |

| *Rwork/Rfree (%) | 16.8/22.5 |

| Figure of Merit | 0.85 |

| Rmsd bond lengths/angles (Å/°) | 0.02/1.79 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 26.7 |

(Values in parentheses are for the last resolution shell)

Rmerge = Σ hkl Σi |Ii(hkl) – 〈I(hkl) 〉| / Σhkl ΣiIi (hkl), where Ii (hkl) is the ith observation of reflection hkl and 〈 I(hkl) 〉 is the weighted average intensity of all observations I of reflection hkl.

Rfactor Σ ‖Fo| − |Fc‖ / Σ |Fo|. Rfree was calculated with 5% of the reflections set aside randomly throughout the refinement.

Structure determination and refinement

Structure determination of XoMCAT was carried out by molecular replacement (MR) using the MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov, 2010) program using malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (MCAT; pdb id: 1mla) from E. coli (Serre et al., 1995) as a template model, which shares 52% sequence identity with XoMCAT. The MR solution structure showed a well fitted electron-density map (2Fo-Fc) for all of the residues, and structural modeling was carried out using the COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) graphics program. Complete structural refinement of XoMCAT was performed using the Refmac 5.1 (Murshudov et al., 1997) program from the CCP4 suite. Visualization and cartoon diagrams were drawn using PYMOL graphics program (Schrodinger, 2010). The pictorial representation of hydrogen bonding and non-bonded interactions for the complexes were derived using the program LIGPLOT (Wallace et al., 1995).

Protein-protein docking

The ligand protein ScACP (pdb id: 2af8) from Streptomyces coelicolor (Schrodinger, 2010) was used for the protein-protein (P-P) docking study. The complex model of XoMCAT/ScACP was constructed using the program ICM MolSoft. The grid potential maps generated from the XoMCAT molecule were defined in a box around the hypothetical binding site, covering approximately half of the XoMCAT surface. The rigid-body docking was performed by sampling different positions and orientations of ScACP molecule with respect to XoMCAT molecule using a Pseudo-Brownian Monto Carlo procedure (Abagyan et al., 1994) implemented in the MolSoft ICM 3.6 program. After complete sampling over the XoMCAT surface was performed, total 23,779 conformations were generated and ranked based on their pairwise shape complementarity (PSC) score. All of the steps were performed using default parameters, which are given in the online manual (http://www.molsoft.com/gui/protprot.html). The top predictions from each cluster were then manually inspected and investigated based on several criteria, such as score, charge complementarity, hydrophobic interactions, and overall agreement with prior biological information.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall structure of XoMCAT

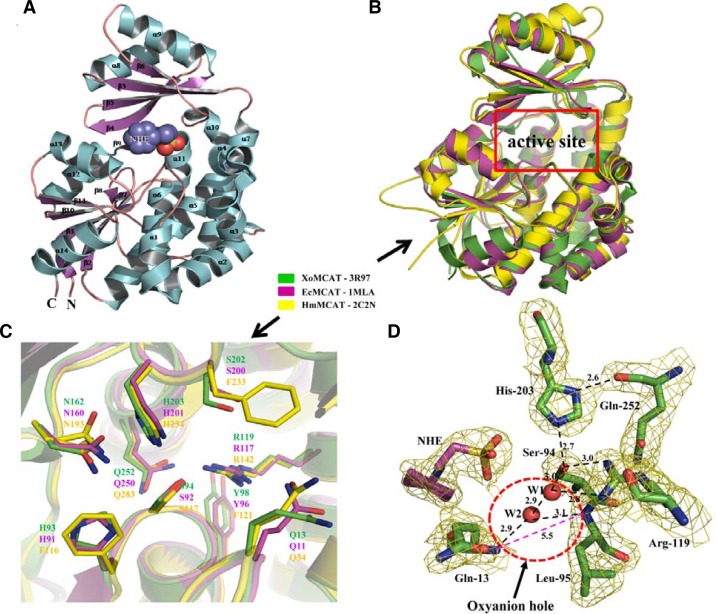

The crystal structure of XoMCAT (Fig. 1A) was determined by MR, and the refined structure coordinate and structure factor was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (pdb id: 3R97). The final model structure was validated using the PROCHECK program (Laskowski et al., 1993), which showed that 91.7% of the residues were located in the allowed region. XoMCAT structure was composed of 14 α-helices and 11 β-strands, and the total accessible surface area was 12,585 Å2. The overall structure of XoMCAT was folded into two subdomains. The large subdomain consisted of two non-contiguous segments formed from-residues 1–129 and from 200–314. The remaining residues were located in the small subdomain. The large subdomain consisted of a short four-stranded parallel β-sheet surrounded by different lengths of 12 α-helices, a long loop with small antiparallel β-strands at the edge, and another β9-strand located between the helices α11 and α12. The smaller subdomain contained four-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet capped by two α-helices.

Fig. 1.

Overall structure of XoMCAT: (A) Cartoon diagram of XoMCAT structure with NHE ligand (space filled diagram) at the active site. (B) Overall structural superposition diagram of XoMCAT (green), EcMCAT (pink), and HmMCAT (yellow). The active site position is indicated by the red box. (C) Residues in the active site of XoMCAT (green), EcMCAT (pink), and HmMCAT (yellow) are illustrated in stick model with labels. (D) The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 1.0 σ level for active site residues and NHE ligand is illustrated. Both the residues (green) and NHE ligand (pink) are shown as a stick model. All hydrogen bonds are indicated in dotted lines. Oxyanion hole distance (pink color) is indicated in the red color dotted ring between the residues, Gln-13 and Leu-95.

Thus far, several MCAT structures from various species have been characterized, such as EcMCAT from Escherichia coli, pdb id: 1MLA (Serre et al., 1995), ScMCAT from Streptomyces, pdb id: 1nm2 (Keatinge-Clay et al., 2003), MtMCAT from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pdb id:2qc3 (Li et al., 2007), HpMCAT from Helicobacter pylori, pdb id: 2h1y (Zhang et al., 2007) and HmMCAT from human mitochondria, pdb id: 2c2n (unpublished). All MCATs including XoMCAT share the similar fold (Fig. 1B), and structural comparison of XoMCAT and other MCATs of EcMCAT, ScMCAT, MtMCAT, HpMCAT and HmMCAT showed the root mean square deviations (r.m.s.d) of 0.74, 1.52, 1.54, 1.37 and 1.35 Å, respectively. Although overall folds of the MCATs are similar, substrate binding pockets surrounding the active site are different. For examples, in HpMCAT, the corresponding residues of XoMCAT α4-helix, which is located close to the pentapeptide (GQGSQ) loop and the nucleophilic elbow containing Ser-94, existed as a loop. In HmMCAT, XoMCAT α14-helix is missing and the part of XoMCAT β11-strand is changed to α-helix, and the areas are known to bind with ACP. EcMCAT has the most similar structure with XoMCAT as shown by the lowest r.m.s.d. value and active site residues are also well conserved (Fig. 1C).

Active site of XoMCAT

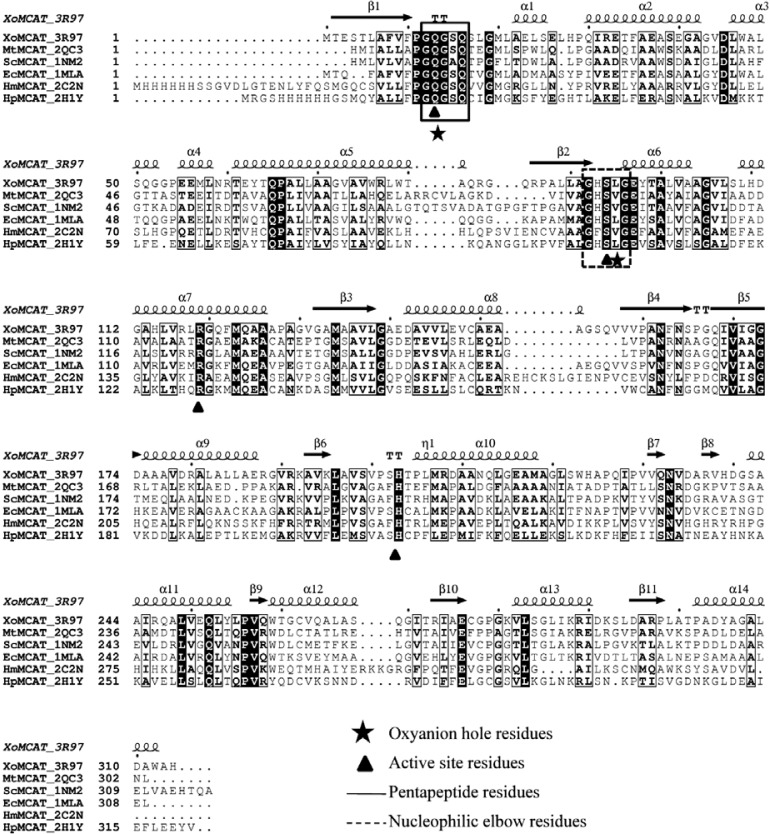

XoMCAT is a serine-dependant hydrolase, and multiple sequence alignment (MSA) analysis (Fig. 2) found that key catalytic residues are strictly conserved. The nucleophilic serine residue (Ser-94) of XoMCAT is located at the center of GHSLG, which is the consensus pentapeptide in the tight turn between β2-strand and α6-helix in the large domain, and called the nucleophilic elbow or β-Ser-α motif (Derewenda and Derewenda, 1991). Residue Ser-94 was located at the disallowed region in the Ramachandran map and it is a characteristic of the active site residue in nucleophilic elbow due to the strain in the enzyme conformation. Another key residue His-203 of XoMCAT located in the deep gorge between the two subdomains, and His-203 and Ser-94 participate in the catalysis reaction along with an oxyanion hole, which was formed between the backbone amide groups of the two residues (Gln-13 and Leu-95) with distances varying from 5.2 to 5.5 Å (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of MCAT structures from various species. The proteins listed from top to bottom: XoMCAT from X. oryzae pv. oryzae; MtMCAT from M. tuberculosis; ScMCAT from S. coelicolor a3, EcMCAT from E. coli, HmMCAT from human mitochondria, and HpMCAT from H. pylori ss1. Secondary structure elements of the MCAT are shown in the top of sequences alignment. Fully conserved residues showed in black box with white characters. The triangles represent the active site residues Gln-13, Ser-94, Arg-119, and His-203. The boxes indicate the conserved nucleophilic elbow (dotted) and GQGXQ pentapeptide (line box) residues. The stars indicate the residues involved in oxyanion hole formation.

MCAT enzymes commonly adopt a ping-pong mechanism for the transfer of a malonyl (MAL) group from malonyl CoA to ACP during FAS (Zhang et al., 2007). A schematic diagram of malonyl CoA binding to MCAT and the transfer of MAL to ACP is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. In the XoMCAT structure, the side chain hydroxyl group of Ser-94 formed a hydrogen bond with NE2 of His-203 (Fig. 1D). The ND1 atom of His-203 acted as a hydrogen bond donor and interacted with the main chain carbonyl oxygen of Gln-252. Another active site residue Arg-119 formed a hydrogen bond (3.0 Å) with the nucleophilic Ser-94 hydroxyl group. Two water molecules, W1 and W2, were found in the active site near to the nucleophilic residue Ser-94. W2 accepted two hydrogen bonds from the main chain amides of residues Leu-95 (3.1 Å) and Gln-13 (2.8 Å) and donated a hydrogen bond to another water, W1 (2.8 Å). W1 accepted a second hydrogen bond from NH1 of Arg-119 (2.7 Å). Reported all MCAT structures had the oxyanion hole, which is located between the backbone amide groups of Gln-13 and Leu-95 in XoMCAT, and the diameter was reduced when substrate bound in the active site: the diameter of the oxyanion hole of EcMCAT/MAL/CoA complex structure (5.2 Å) (Oefner et al., 2006) is narrower than that in the apo EcMCAT (pdb id: 1mla) structure (5.4 Å). The diameter of the oxyanion hole in XoMCAT was wider (5.5 Å) than those of both apo and complex EcMCAT (Supplementary Table S1). The variation in the size of the oxyanion hole influences the catalytic activity of MCAT.

It is interesting to note that the solvent molecule, N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethansulfonic acid (NHE), was tightly bound in the substrate binding site. Asn-162 formed a hydrogen bond with NHE. Residue Ser-202 also formed a hydrogen bond with NHE, and His-93 interacted with the NHE molecule via a water molecule. The tight interaction of NHE molecule with His-93 and Ser-202 in the substrate binding pocket could be used to design an inhibitor to XoMCAT.

Proposed catalytic mechanism

Generally proposed catalytic reaction of MCAT can be divided into two parts (Joshi and Wakil, 1971): formation of MCAT/ malonyl CoA complex and formation of the MCAT/MAL/ACP complex via activation of the oxyanion hole (Zhang et al., 2007). In the first part of the reaction, the oxyanion hole is activated when malonyl CoA binds with MCAT. We tried to obtain the XoMCAT structure in complex with malonyl CoA in various ways. However, no obvious extra-density in the active site was observed in the co-crystal structures. Instead, the EcMCAT/ MAL/CoA complex structure (pdb id: 2g2z) (Oefner et al., 2006) was taken as a model to analyze the interaction between XoMCAT and malonyl CoA. The amino acid sequences of E. coli and XoMCAT shared 52% sequence identity, and r.m.s.d between the structures was 0.74 Å. The cartoon diagram of the structure comparison between EcMCAT/MAL/CoA and XoMCAT is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2A. The interactions between CoA and active site residues including hydrogen bond interactions (Ser-165, Pro-166, and Asn-162) and hydrophobic interactions (Gly-139 & 167, Val-282, and Gln-168) were conserved in XoMCAT (Supplementary Fig. S2B). MAL binding residues (Gln-13, Ser-94, Arg-119, and His-203) close to the oxyanion hole were well conserved. Especially Gln-13, located in the highly conserved pentapeptide GQGXQ near the active site, was also involved in the formation of an oxyanion hole. In the second part of the MCAT catalytic mechanism in FAS, ACP binds to the surface of MCAT/MAL/CoA complex and the ACP binding pushes the Gln-13 toward Leu-95, which causes the activation of the oxyanion hole to release the MAL group to form MAL-ACP.

Computational protein-protein docking (XoMCAT/ScACP)

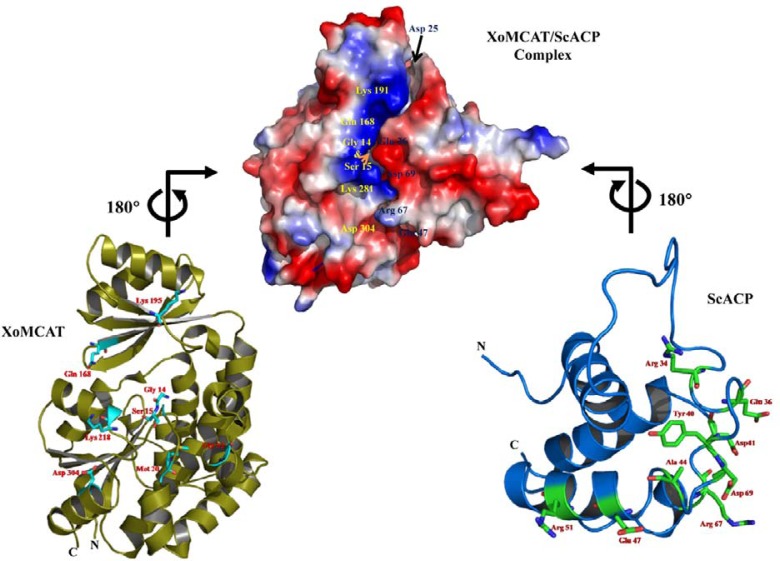

MCAT has two structural important motifs related to its biological function; one is the catalytic active site and the other is the ACP-binding site on its surface (Serre et al., 1995). Study of the interaction between MCAT and ACP is very interesting due to the role of ACP to transfer the malonyl group in Type II FAS. Thus far, no crystal structure of MCAT complexed with ACP has been reported. We used P-P computational docking to investigate the interaction between XoMCAT and ACP. The reported ScACP structure from S. coelicolor was taken as the ACP model for the P-P docking study (Serre et al., 1995). The optimized complex model of XoMCAT/ScACP was calculated as described in materials and methods. The MolSoft ICM suit generated 23,779 conformations of the protein complex, and the top scored molecule was selected based on the energetically favorable conformation of XoMCAT and ScACP based on the surface electrostatic potential. In the best scored model, ScACP bound at the groove between the two subdomains in XoMCAT near the entrance of the active site. The ACP binding site of XoMCAT was located adjacent to the GQGXQ loop including the oxyanion hole forming Gln-13 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Zhang et al. (2007) proposed HpMCAT/HpACP complex structure via molecular docking and the model suggested that two positively charged areas of HpMCAT near its active site would bind to the negatively charged surface of HpACP. Our XoMCAT/ScACP complex model showed that the same positively charged binding areas of XoMCAT bound to the negatively charged areas of ScACP (Fig. 3), however in a different orientation: the binding areas of XoMCAT and ScACP were similar with the corresponding areas of HpMCAT and HpACP, however the binding orientation of ScACP was approximately 180° rotated from the HpACP binding orientation along the XoMCAT/ScACP binding axis. In order to prove the detail interaction between XoMCAT and XoACP, the co-crystal structure would be essential.

Fig. 3.

Protein-protein docking: docking model of XoMCAT/ScACP complex with important residues (cyan and green residues) for electrostatic interactions and cartoon structures of XoMCAT and ScACP with binding residues (stick model).

Based on our XoMCAT/ScACP complex structure, the residues Lys-195, Lys-281, Asp-304 and Gln-168 of XoMCAT interacted with the oppositely charged residues of ScACP (Asp-41, Asp-69, Glu-36, Asp-25, and Arg-67) in the form of salt bridges and hydrogen bonds (Supplementary Table S2). Other residues of Met-20, Gly-14, Ser-15, and Gly-52 in XoMCAT also formed hydrogen bonds with Glu-47, Tyr-40, Ala-44, and Gly-52 of the ScACP protein. The hydrophobic residues in a long loop of ScACP interacted with the residues of XoMCAT (β3 & β6 and core of helical bundle of the large catalytic domain) (Supplementary Table S3). The loop residues of ScACP recognized the electropositive/hydrophobic residues near the active site entrance of XoMCAT and stacked in the binding groove between the two subdomains on the surface. Remarkably, almost all interfacial residues of XoMCAT involved in the p-p interaction were conserved in most MCATs.

Two hydrogen bond interactions between the backbone carbonyls of Gly-14 and Ser-15 of XoMCAT and ACP residues are important because the XoMCAT residues are a part of the conserved pentapeptide loop (GQGXQ) near the oxyanion hole (Supplementary Table S2). The interaction could activate the oxyanion hole, and initiate the malonyl transfer to ACP, which was not mentioned in HpMCAT/HpACP docking model. The study of XoMCAT/ScACP complex structure suggests that XoMCAT directly binds to ACP and helps to transfer the malonyl group for further FAS. All of these findings would be helpful to understand the catalytic mechanism of MCAT and develop antibacterial agents against BB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. K.J. Kim and Dr. Y.G. Kim for their assistance with the beamline 4A and 6C at the Pohang Light Source (PLS), South Korea, and to staff members at the beamline 17A of the photon factory (KEK), Japan. This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (No. 2010-0011666 and No. 2011-0027928), and by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ008174), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by Korean Government (NRF-2011-619-E0002).

Note:

Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Abagyan R.A., Totrov M.M., Kuznetsov D.A. Icm: A new method for protein modeling and design: applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J. Comp. Chem. 1994;15:488–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J.W., Cronan J.E., Jr. Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis: targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:305–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda Z.S., Derewenda U. Relationships among serine hydrolases: evidence for a common structural motif in triacylglyceride lipases and esterases. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1991;69:842–851. doi: 10.1139/o91-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezuka A K.H. A histrorical review of bacterial blight of rice. Bull. Natl. Inst. Agrobiol. Resour. (Japan) 2000;15:53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V.C., Wakil S.J. Studies on the mechanism of fatty acid synthesis. XXVI. Purification and properties of malonylcoenzyme A--acyl carrier protein transacylase of Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971;143:493–505. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J.W., Natarajan S., Kim H., Ahn Y.J., Kim S., Kim J.G., Lee B.M., Kang L.W. Cloning, expression, crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of malonyl-CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (FabD) from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Acta. Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2008;64:1143–1145. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108035331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay A.T., Shelat A.A., Savage D.F., Tsai S.C., Miercke L.J., O’Connell J.D., 3rd, Khosla C., Stroud R.M. Catalysis, specificity, and ACP docking site of Streptomyces coelicolor malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase. Structure. 2003;11:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R., MacArthur M., Moss D., Thornton J. PROCHECK: a program to check the sterochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.M., Park Y.J., Park D.S., Kang H.W., Kim J.G., Song E.S., Park I.C., Yoon U.H., Hahn J.H., Koo B.S., et al. The genome sequence of Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae KACC10331, the bacterial blight pathogen of rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:577–586. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Huang Y., Ge J., Fan H., Zhou X., Li S., Bartlam M., Wang H., Rao Z. The crystal structure of MCAT from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals three new catalytic models. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K., Jackowski S., Rock C.O., Cronan J.E., Jr. Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesel L., Greene J., Black T.A. Genetic strategies for antibacterial drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:442–456. doi: 10.1038/nrg1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Dodson E.J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oefner C., Schulz H., D’Arcy A., Dale G.E. Mapping the active site of Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (FabD) by protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:613–618. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906009474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D.J., Gwynn M.N., Holmes D.J., Rosenberg M. Genomic approaches to antibacterial discovery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;266:231–259. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-763-7:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D.J., Gwynn M.N., Holmes D.J., Pompliano D.L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruch F.E., Vagelos P.R. The isolation and general properties of Escherichia coli malonyl coenzyme A-acyl carrier protein transacylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:8086–8094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1. 2010.

- Serre L., Verbree E.C., Dauter Z., Stuitje A.R., Derewenda Z.S. The Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase at 1.5-A resolution. Crystal structure of a fatty acid synthase component. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12961–12964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers R.G., Ali A., Shen B., Wessel W.A., Hutchinson C.R. Malonyl-coenzyme A: acyl carrier protein acyltransferase of Streptomyces glaucescens: a possible link between fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9389–9402. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A., Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace A.C., Laskowski R.A., Thornton J.M. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of proteinligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S.W., Zheng J., Zhang Y.M., Rock The structural biology of type II fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:791–831. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.J., Kang J.Y., Mikami B., Lee H.H., Suh S.W. Crystal structure of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase from Enterococcus faecalis in the ligand-unbound state and in complex with ATP and pantetheine. Mol. Cells. 2011;32:431–435. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0102-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liu W., Xiao J., Hu T., Chen J., Chen K., Jiang H., Shen X. Malonyl-CoA: acyl carrier protein transacylase from Helicobacter pylori: crystal structure and its interaction with acyl carrier protein. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1184–1192. doi: 10.1110/ps.072757307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.