Abstract

Previous studies have shown that Notch signaling not only regulates the number of early differentiating neurons, but also maintains proliferating neural precursors in the neural tube. Although it is well known that Notch signaling is closely related to the differentiation of adult neural stem cells, none of transgenic zebrafish provides a tool to figure out the relationship between Notch signaling and the differentiation of neural precursors. The goal of this study was to characterize Her4-positive cells by comparing the expression of a fluorescent Her4 reporter in Tg[her4-dRFP] animals with a GFAP reporter in Tg[gfap-GFP] adult zebrafish. BrdU incorporation indicated that dRFP-positive cells were proliferating and a double labeling assay revealed that a significant fraction of the Her4-dRFP positive population was also GFAP-GFP positive. Our observations suggest that a reporter line with Notch-dependent gene expression can provide a tool to examine proliferating neural precursors and/or neuronal/glial precursors in the development of the adult nervous system to examine the model in which Notch signaling maintains proliferating neural precursors in the neural tube.

Keywords: adult brain, GFAP, Her4, neural precursor, Notch, transgenic zebrafish

INTRODUCTION

The spatial and temporal differentiation of neural stem cells and/or neural precursors gives rise to the diversity and complexity of neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) (Ma et al., 2005; Yeo and Chitnis, 2007). Previous studies have shown that Notch signaling not only regulates the number of early differentiating neurons but also maintains proliferating neural precursors in the neural tube (Yeo and Chitnis, 2007). These previous studies led to the generation of transgenic zebrafish in which the spatiotemporal pattern of Notch activation can be examined in vivo (Yeo et al., 2007). Analysis of Tg[her4-fluorescent reporter] transgenic zebrafish has shown that while both the expression of proneural genes and the activation of Notch were critical for endogenous her4 expression, the reporter gene expression is primarily regulated by Notch activity alone (Yeo et al., 2007).

In limited regions of the adult mammalian CNS, neurogenesis occurs within niches that regulate the neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells (Ma et al., 2005). Previous reports have suggested that glial cells, including astrocytes, play a key role in controlling adult neurogenesis (Ma et al., 2005). In mammals, a key attribute of neural stem cells is the expression of the filament forming proteins glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and Nestin (Kempermann et al., 2004; Lendahl et al., 1990). In zebrafish, transgenic animals have been generated as tools to further the understanding of the roles of glia during CNS development in vivo (Bernardos and Raymond, 2006; Lam et al., 2009). However, although the relationship between Notch signaling and the differentiation of adult neural stem cells has been investigated in mammals, there has been no transgenic analysis of this relationship in zebrafish. The goal of this study was to characterize Her4-positive cells by comparing the expression of the fluorescent Her-4 reporter in Tg[her4-dRFP] zebrafish with that of the fluorescent GFAP reporter in Tg[gfap-GFP] zebrafish.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish lines

Zebrafish were maintained as described by Yeo et al. (2007). The lines used in this study were: AB* wild-type, Tg[her4-nlsGFP], Tg[her4-dRFP] (Yeo et al., 2007), Tg[gfap-EGFP] (Bernardos and Raymond, 2006), and Tg[her4-UAS].

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Dam et al., 2011). Antisense riboprobes were transcribed from cDNA for zebrafish notch3 and jagged1a. Photos were taken with a differential interference contrast microscope (Axioplan2; Carl Zeiss).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described by So et al. (2009). For immunostaining, anti-Myc (1/5000, Santa Cruz) and anti-BrdU (1/1000, Sigma) antibodies were used. Whole-mount immunostaining was performed as described by So et al. (2009) with a minor modifaction. The brains were removed from adult zebrafish and fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The specimens were immersed in 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4°C, frozen in OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical), and sectioned at 12–14 μm with a cryostat. Cryosections were washed once with PBST and twice with PBST (PBS, 1% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100), and incubated in 5% goat serum (Vector), PBS-T at RT for 1 h. The samples were incubated with the primary antibody solution at 4°C overnight. After four washes with PBST, the samples were incubated with secondary antibodies (1/1000 dilution, Alexa Fluor 488 and/or Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse and/or goat anti-rabbit IgG, Molecular Probes). For two-color staining with two mouse monoclonal antibodies. The Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector) was also used for immunostaining with the HRP substrate diaminobenzidine (DAB). When the samples were stained with a riboprobe and antibody, in situ hybridization (NBT/BCIP staining) was performed first, followed by immunostaining (DAB).

BrdU incorporation

BrdU incorporation was performed as previously described with a minor modifaction (Yeo and Chitnis, 2007). Adult zebrafish were kept in 100 mM BrdU (5′-bromo-2′ deoxyuridine, Sigma) solution for 1 h (short-term exposure) for 24 h (long-term exposure). Exposing the fish to the treated water allowed uptake of the thymidine analog, presumably via the gills. Fish were returned to small aquaria containing tank water that was changed every 0.5 for 2 h (to minimize reuptake of excreted BrdU). The brains were removed and fixed in 4% PFA in PBS. The cryosections were treated with 2 N HCl for 30 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, 0.1% Tween20, neutralized twice with 0.1 M Na2B4O7, and washed twice with PBS, 0.1% Tween20. Immunostaining was carried out as described above.

Cell transplantation

Eggs were collected and dechorionated by treatment with pronase in egg water solution. Eggs from Tg[her4-dRFP];Tg[gfap-GFP] double transgenic were to serve as donors without a mixture of fluorescein-dextran, rhodamine-dextran and phenol red. Cell transplants were performed on embryos at the mid-blastula stage (4-hpf). Cell transplants were done with a micro pipette whose tip had been pulled in a flame to achieve a bore size of 2–3 cell diameters, and most were performed by hand. A few were performed with the aid of a micromanipulator. Donor cells were loaded by suction from a donor specimen and then injected among the superficial cells of a recipient blastoderm at approximately the 1000-cell stage, without damage to the yolk cell. As few as 5 or as many as about 20 cells were injected into a single embryo in different experiments, under a dissecting microscope. Confocal images were taken at 28-hpf and 60-hpf.

RESULTS

Her4-positive cells are proliferating precursor in the tectum opticum of adult zebrafish

To characterize the Her4-positive cells in adult zebrafish, Tg[her4-dRFP] and Tg[her4-nlsGFP] fish were exposed to 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Fig. 1). BrdU can be incorporated into the genomic DNA of proliferating cells. Cells which have incorporated BrdU into their DNA can be detected using a monoclonal antibody against BrdU. The cells are treated with 2 N HCl to denature the DNA and then stained with the BrdU antibody. However, when tissue sections from Tg[her4-dRFP] and Tg[her4-nlsGFP] zebrafish brains were exposed to HCl, the fluorescence of the reporter proteins was quenched. To solve this problem, we performed double-labeling immunofluorescence using anti-BrdU and anti-Myc antibodies, since dRFP and nlsGFP are both tagged with 6 repeats of the Myc epitope (Yeo et al., 2007, see the “Materials and Methods”).

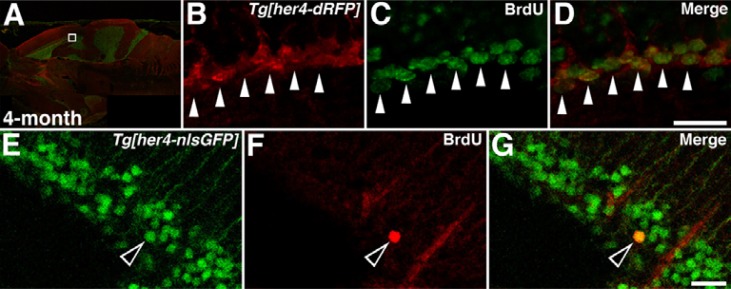

Fig. 1.

BrdU-labeling reveals proliferating neural precursor cells in the adult brain of 4-month-old Tg[her4-reporter] zebrafish. Sagittal-section and left anterior views are shown. (A-D) Long-term exposure (24 h) of Tg[her4-dRFP] animals to BrdU. Confocal images identify dRFP (B, red) and BrdU (C, green) labeling in the adult Tg[her4-dRFP] brain (A). High magnification views of the boxed area in A (B–D). White arrowheads indicated BrdU- and dRFP-positive cells in the tectum opticum (TeO). (E–G) Short-term exposure (1 h) of Tg[her4-nlsGFP] animals to BrdU. Confocal images identify GFP (E, green) and BrdU (F, red) labeled nuclei in the adult brain of Tg[her4-nlsGFP] animals. Open arrowheads indicate BrdU- and GFP-positive nuclei in the TeO. Scale bars 25 μm.

A large population of BrdU-positive cells was detected in the adult zebrafish cerebellum and tectum opticum (TeO) after a long-term exposure to BrdU (Fig. 1A). Double-labeling experiments revealed that most of BrdU-positive cells in TeO were also dRFP-positive (Figs. 1B–1D). Although double-labeling experiments implicated that the majority of dRFP-positive cells were the proliferating cells, it needs to be defined that all the new born neural progenitor in the ventricular zone of adult nervous system was solely proliferating one. To address this, we performed the short-term BrdU incubation using Tg[her4-nlsGFP] zebrafish (Figs. 1E–1G). A small number of BrdU-positive cells were observed in the TeO after a 1 h of BrdU administration (Fig. 1F). Double-labeling experiments revealed that all the nucleus of BrdU-positive cells in the TeO was also overlapped with that of GFP-positive (Fig. 1G). These data are consistent with the ideas that Notch signaling maintains proliferating neural precursors in the neural tube (Yeo and Chitnis, 2007). The data further suggest that a fluorescent reporter line carrying a Notch-Su(H)-dependent gene can provide a tool suitable for examining the proliferating cells in the neural development of the adult nervous system.

Expression of notch3 and jagged1a in the adult brain

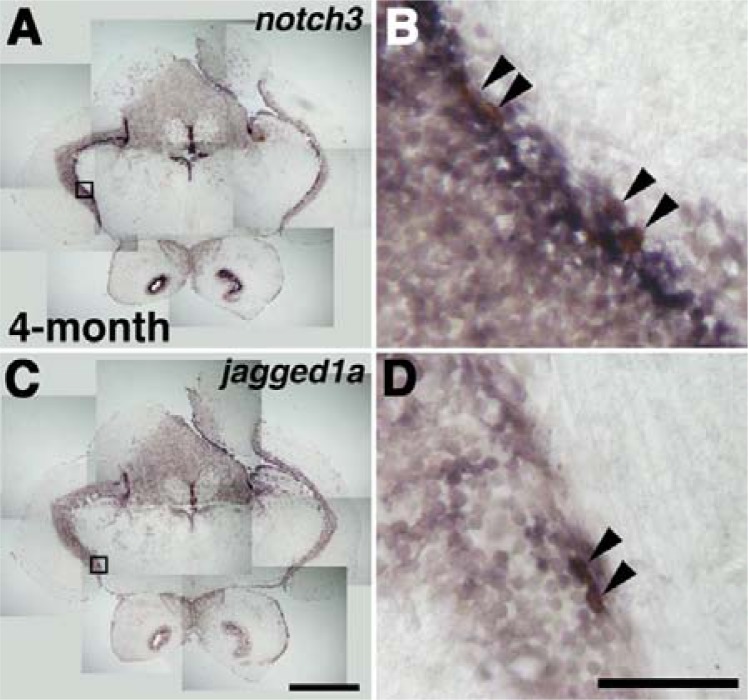

To determine whether de novo neurogenesis occurs in the TeO, we examined the expression of several genes involved in the neurogenic cascade (Yeo and Chitnis, 2007; Yeo et al., 2007). We observed that notch3 and jagged1a were expressed within the TeO of zebrafish adult brain (Figs. 2A and 2C). After 1 h of BrdU incubation, the majority of BrdU positive cells were found in the expression domain of notch3 and jagged1a in the TeO. At high magnification views, BrdU positive cells expressed notch3. While jagged1a expression partially overlapped with BrdU positive cells, rather jagged1a was more intensively expressed in the surrounding cells of BrdU positive ones (Figs. 2B and 2C). These data imply that the molecular factors able to mediate the Notch signaling are present in the TeO area, and Tg[her4-fluorescent protein] reporter lines could mimic the expression of such molecular factors.

Fig. 2.

Expression of notch3 and jagged1a in the adult brain. Cross-section views are shown. The transcripts of notch3 (A, dark blue) and jagged1a (C, dark blue) are detected in tectum opticum (TeO) of 4-month-old zebrafish brain. High magnification views of the boxed area in (A) and (C) (B and D, respectively). Arrowheads indicate BrdU-positive cells. Scale bars 100 μm.

Her4-positive cells are GFAP-positive in the adult brain of zebrafish

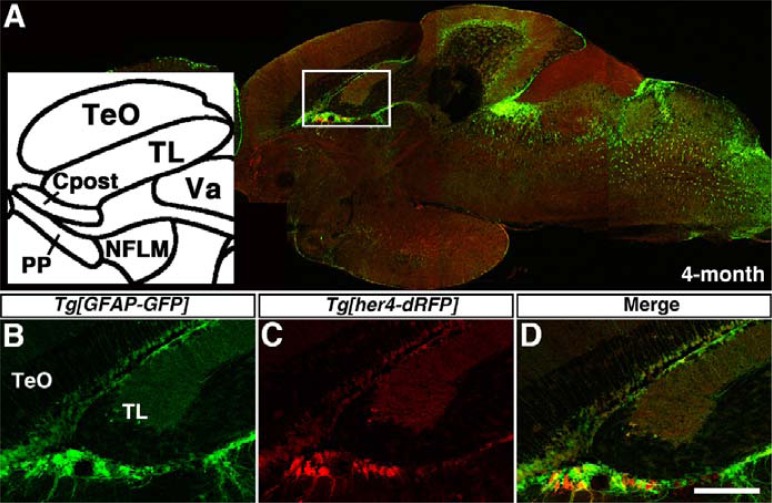

GFAP, an intermediate filament protein, is expressed in astrocytes and radial glial cells as neuronal/glial precursors (Eng et al., 2000). The vertebrate GFAP regulatory elements have been previously used to generate transgenic lines that express GFP in the neuronal/glial precursors of adult zebrafish (Bernardos and Raymond, 2006). To confirm whether a reporter line with Notch-Su(H)-dependent expression of fluorescent proteins marks neural precursors in the vertebrate nervous system, we generated the double transgenic zebrafish by mating Tg[her4-dRFP] and Tg[gfap-GFP] zebrafish (Fig. 3). Confocal image of para-sagittal section showed that most of dRFP and GFP labeled cells were co-localized together in the restricted brain region of the four-month old Tg[her4-dRFP];Tg[GFAP-GFP] double transgenic zebrafish (Fig. 3A). High magnification views reveal that a signicant population of dRFP-positive cells in TeO was also GFP-positive (Figs. 3B–3D). Although the majority of dRFP-positive cells expressed GFP, more intensive red fluorescence than green one was observed in some cells of the commissural postoptica (Cpost), the periventricular pretectum (PP), and the nucleus of the medial longitudinal fascicle (nMLF) (Fig. 3D). These data suggested that dRFP-positive cells are neural/glial precursors, and further provided the possibilities that dRFP-positive neural/glial precursors are a heterogenous and/or the stability of dRFP differs from that of GFP.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of fluorescent protein expression in Tg[her4-dRFP] and Tg[GFAP-EGFP] transgenic zebrafish. Sagittal-section and left anterior views are shown. Confocal images identify dRFP (red, C) and EGFP (green, B) labeled cells in the adult brain of Tg[her4-dRFP];Tg[GFAPEGFP] double transgenic zebrafish at 4 months of age (A). High magnification views of the boxed area in (A) (B–D). Cpost, commissural postoptica; nMLF, nucleus of the medial longitudinal fascicle; PP, periventricular pretectum; TeO, tectum opticum; TL, torus longitudinalis; Va, valvula cerebella. Scale bars 50 μm.

Cell transplantation analysis reveals the differential expression of fluorescent proteins

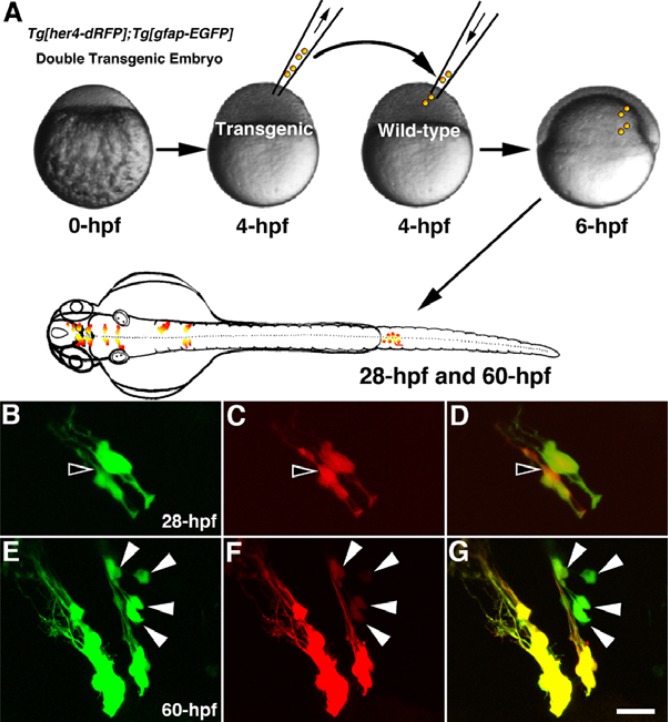

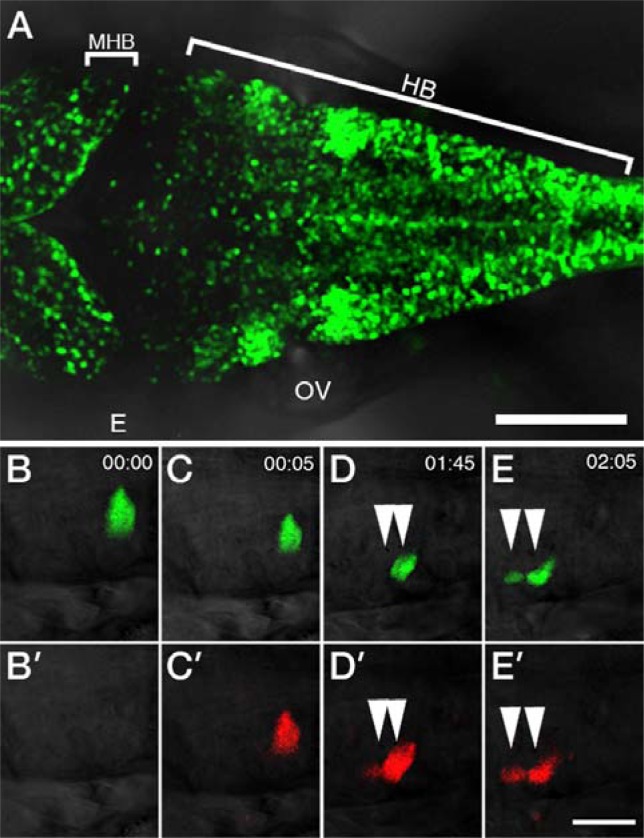

To test these possibilities, we performed cell transplantation experiments (Fig. 4A). When the cells derived from Tg[her4-dRFP];Tg[GFAP-GFP] double transgenic embryos were transplanted into wild type embryos, the fluorescent labeled cells could be easily observed without interference of the fluorescent neighboring ones (Figs. 4B–4G). In this way, multi-lineage transplanted engraftment efficiency can be monitored in a real-time manner in living recipient animals. It was notable that all the GFP positive cells were identified as dRFP-positive ones. Interestingly, a cell colored with more intensive red fluorescence than that of green fluorescence at 28-hpf (Fig. 4D) and vice versa at 60 hpf (Fig. 4G). Additionally, we performed genetic mosaic analysis by injecting UAS-EosFP DNA constructs into Tg[her4-Gal4] transgenic embryos at 1-cell stage (Fig. 5A). After selecting an embryo, photo-conversion was performed at 34 hpf using UV microscope. Time-lapse images show the proliferating cells in the hindbrain (Figs. 5B–5E).

Fig. 4.

Cell transplantation analysis reveals the differential expression of fluorescent proteins in the Tg[her4-dRFP];Tg[GFAP-EGFP] embryos. Left anterior views are shown. (A) Diagram shows the procedure of cell transplantation. Confocal images show the expression of dRFP (red, D, F) and EGFP (green, B, E) in the diencephalon at 28 hpf (B–D) and 60 hpf (E–G). Open arrowheads indicate the relatively strong dRFP-positive cells (B–D). White arrowheads indicate the relatively strong EGFP-positive cells (E–G). Scale bars 25 μm.

Fig. 5.

Mosaic analysis reveals the proliferating cells in the Tg[her4-Gal4] embryos. Left anterior views are shown. (A) Confocal images of Tg[her4-Gal4]; Tg[UAS-EGFP] embryos at 48 hpf. (B–E) Time-lapse images show the expression of EosFP in the hindbrain from 34 hpf (B) to 36 hpf (E). UAS-EosFP DNA was injected into Tg[her4-Gal4] fertilized eggs. Photo-conversion was performed at 34 hpf using UV microscope (C′–E′). White arrowheads indicate the proliferating cells in the hindbrain. MHB, mid-hindbrain boundary; HB, hindbrain; E, eye; OV, otic vesicle. Scale bars 100 μm (A) and 25 μm (B–E).

The differences in fluorescent intensity may be caused by reduced stability of the dRFP (Yeo et al., 2007). Time-lapse images of double transgenic Tg[her4:nlsEGFP];Tg[her4:dRFP] animals showed that the dRFP signal started to degrade after 2.5 h and was largely diminished after 4.5 h, while the EGFP signal persisted at the same level in the same cells of the spinal cord (Yeo et al., 2007). This observation demonstrated that dRFP is less stable than EGFP in vivo (Yeo et al., 2007). Although the comparison between GFP and dRFP fluorescence intensity in the transgenic fish identified important distinctions, analysis of the transgenic reporter lines demonstrated that these transgenes are effective reporters of Notch activity, particularly in the CNS. Thus, the differences in fluorescent intensity may also be caused by differences in promoter activity between her4 and gfap.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have carried out immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, both at single-cell resolution in an adult vertebrate brain. Expression of a Notch and its ligand in TeO of the adult zebrafish brain provided an explanation of fundamental reasons of this study. Additionally, long-term and short term exposure of BrdU showed that large number of proliferating progenitors were located in TeO of the adult zebrafish brain. Analyses of the transgenic reporter lines demonstrated that these transgenes are excellent readout of Notch activity, particularly in the CNS. Our observations suggest that a fluorescent reporter line carrying a Notch-dependent reporter gene provides a tool to explore the proliferating neural precursors and/or neuronal/glial precursors during development of the adult nervous system. Gal4 transgenic zebrafish under control of her4 promoter can be used to study gene expression and function in a tissue-specific manner.

Expression of a Notch and its ligand in the adult zebrafish brain

Previous study showed that Jagged2 and Jagged1b knock-down allow progenitors to prematurely differentiate into neuron at early neurogenesis (Gwak et al., 2010). Based on our observation, we suggested that the combined functions of the Jagged2- and Jagged1b-mediated Notch signaling are necessary for the in vivo maintenance of progenitors during later development (Gwak et al., 2010). In adult zebrafish brain, however, transcripts of Jagged2, Jagged1a as well as Delta homologs were undetectable by in situ hybridization, especially in TeO region (data not shown). Our observation showed that only jagged1b among Notch ligands is strongly expressed at the adult zebrafish brain. Furthermore, the expression pattern of Jagged1b is very similar to that of Notch3 and that of reporter of her4 transgenics. Although Delta-mediated Notch signaling is necessary for the differentiation of neural stem cell both qualitatively and quantitatively (Grandbarbe et al., 2003), our observation strongly suggests that the Jagged1b-mediated Notch signaling pathway is required for the maintenance of neural progenitors in the adult zebrafish brain, but not Delta-mediated. Our observations strongly support the idea that individual subtypes of Notch and their ligands, Jaggeds or Deltas, contribute in their ways to the building of the overall neural architecture, though the function of Notch signaling pathway is preserved during evolution and development (Gwak et al., 2010). Our results implicate that the function of the Jagged1b-mediated Notch3 signaling pathways are indispensable for the maintenance of the neural progenitors during adult neural development as well as the construction of the surrounding microenvironment, niche.

Zebrafish as a model animal for the adult neurogenesis

In the adult mammalian brain, subset of glia only in the dentate gyrus of hippocampus and in the subventricle zone (SVZ) act as multipotent neural stem cells (Ninkovic and Götz, 2007). These cells generate neurons and glia, becoming transit-amplifying precursors and then precursors that express neuronal progenitors (Ninkovic and Götz, 2007). However, many neuronal progenitors not only differentiate into neuronal cells, but also generate glia in an altered environment (Ninkovic and Götz, 2007). To figure out the idea whether the local environment, niche, is necessary for various steps of lineage progression in the adult brain or not (Ninkovic and Götz, 2007), a new animal model is required.

Many developmental biologists have had the choice of using zebrafish as their animal model, because of the rapid development, transparence of its embryo, the amount of fertilized egg and easy maintenance etc. Among them, it is a strong advantage that zebrafish is a vertebrate. From neurogenesis to organogenesis, from genetics to behavior, its application stands high in public estimation. In this respect, our study provides a tool for gain-of-function study by generating Gal4 transgenic zebrafish under control of her4 promoter, being of a help toward the field of the adult neurogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the members of the Yeo laboratory. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0070918).

REFERENCES

- Bernardos R.L., Raymond P.A. GFAP transgenic zebrafish. Gene Expr. Pattern. 2006;6:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam T.M., Kim H.T., Moon H.Y., Hwang K.S., Jeong Y.M., You K.H., Lee J.S., Kim C.H. Neuron-specific expression of scratch genes during early zebrafish development. Mol. Cells. 2011;31:471–475. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng L.F., Ghirnikar R.S., Lee Y.L. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: GFAP-thirty-one years (1969–2000) Neurochem. Res. 2000;25:1439–1451. doi: 10.1023/a:1007677003387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbarbe L., Bouissac J., Rand M., Hrabe de Angelis M., Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Mohier E. Delta-Notch signaling controls the generation of neurons/glia from neural stem cells in a stepwise process. Development. 2003;130:1391–1402. doi: 10.1242/dev.00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak J.W., Kong H.J., Bae Y.K., Kim M.J., Lee J., Park J.H., Yeo S.Y. Proliferating neural progenitors in the developing CNS of zebrafish require Jagged2 and Jagged1b. Mol. Cells. 2010;30:155–159. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G., Jessberger S., Steiner B., Kronenberg G. Milestones of neuronal development in the adult hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam C.S., Marz M., Strahle U. gfap and nestin reporter lines reveal characteristics of neural progenitors in the adult zebrafish brain. Dev. Dyn. 2009;238:475–486. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U., Zimmerman L.B., McKay R.D. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.K., Ming G.L., Song H. Glial influences on neural stem cell development: cellular niches for adult neurogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninkovic J., Götz M. Signaling in adult neurogenesis: from stem cell niche to neuronal networks. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;17:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So J.H., Chun H.S., Bae Y.K., Kim H.S., Park Y.M., Huh T.L., Chitnis A.B., Kim C.H., Yeo S.Y. Her4 is necessary for establishing peripheral projections of the trigeminal ganglia in zebrafish. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;379:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S.Y., Chitnis A.B. Jagged-mediated Notch signaling maintains proliferating neural progenitors and regulates cell diversity in the ventral spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5913–5918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607062104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S.Y., Kim M., Kim H.S., Huh T.L., Chitnis A.B. Fluorescent protein expression driven by her4 regulatory elements reveals the spatiotemporal pattern of Notch signaling in the nervous system of zebrafish embryos. Dev. Biol. 2007;301:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]