Abstract

Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 2 (ERK2) plays many vital roles in cellular signal regulation. Phosphorylation of ERK2 leads to propagation and execution of various extracellular stimuli, which influence cellular responses to stress. The final response of the ERK2 signaling pathway is determined by localization and duration of active ERK2 at specific target cell compartments through protein-protein interactions of ERK2 with various cytoplasmic and nuclear substrates, scaffold proteins, and anchoring counterparts. In this respect, dimerization of phosphorylated ERK2 has been suggested to be a part of crucial regulating mechanism in various protein-protein interactions. After the report of putative dimeric structure of active ERK2 (Canagarajah et al., 1997), dimeric model was employed to explain many in vivo and in vitro experimental results. But more recently, many reports have been presented questioning the validity of dimer hypothesis of active ERK2. In this review, we summarize the various in vitro and in vivo studies concerning the Monomeric or the dimeric forms of ERK2 and the validity of the dimer hypothesis.

Keywords: ERK2, MAP kinase, nuclear translocation, phosphorylation, scaffold protein

INTRODUCTION

Sustaining healthy individual cells is vital to the survival of a multicellular organism. To this end, living organisms have evolved a delicate mechanism involving cell proliferation, division, and self-termination. And the same signaling mechanism is often involved in diverse, and sometimes contradictory, life-or-death decisions in single living organisms. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are involved in diverse cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, inflammatory response, cell-death, migration, and survival (Chang and Karin, 2001; Chaudhary et al., 2000; Eblen et al., 2004; Jain et al., 1998; Pages et al., 1993). The MARK family in humans includes c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3) (Derijard et al., 1994; Fanger et al., 1997; Kyriakis et al., 1994), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK1 and ERK2) (Volmat and Pouyssegur, 2001; Yoon and Seger, 2006), p38s p38α, p38β, p38γ, p38δ) (Han et al., 1994), ERK5, ERK3s (ERK3, p97 MAPK, ERK4) (Lee et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 1995) and ERK7s (ERK7, ERK8) subfamilies; many are conserved in diverse organisms. MAPK cascades are delicate signal relaying mechanisms initiated from several extracellular stimuli. Cytokines, hormones, growth factors (Sasagawa et al., 2005; Schoeberl et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2000; Xie et al., 1998; Yujiri et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2003) including tumor necrosis factor, nerve growth factor, epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor β and diverse environmental stresses (Kyriakis et al., 1994; Rosette and Karin, 1996) stimulate MAPK signaling pathways. Signals are propagated through three-tiered protein kinase cascades: MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK), MAPK kinase (MAPKK, also abbreviated MEK) and MAPK. Upon external stimuli, the Ras or Rho family of small GTPases activate MAPKKK, which, in turn, activates a sequential chain MAPK cascade through MAPKKK, MAPKK and, finally, MAPK. MAPK either stays in the cytoplasm or translocates into the nucleus, relaying external stimuli to specific substrate by phosphorylation.

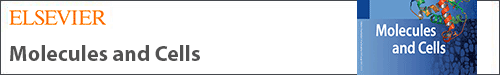

The ERK2 cascade, which is a central and ubiquitous signaling pathway, utilizes Raf, MEKs and ERKs as its kinase components. Activation of receptors, like receptor tyrosine kinase, epidermal growth factor receptor or G protein-coupled receptor by extracellular stimuli initiates signal propagation by recruiting an adaptor protein, Grb2, and guanidine nucleotide exchange factor, SOS (Cussac et al., 1999). Plasma membrane-anchored Ras, when activated by SOS, activates Raf by phosphorylating multiple phosphorylation sites (Farrar et al., 2000). Phosphorylated Raf activates the dual specificity kinases MAPKK MEK1 and MEK2 (S217 and S221 in MEK1, S222 and S226 in MEK2). Phosphorylation of threonine and tyrosine residues in the TEY (Thr202-Glu-Tyr204) motif at the activation loop by MEKs opens the catalytic site in ERK2 (Roux and Blenis, 2004) and its activity increases by 1000-fold, compared with inactive ERK2 (Payne et al., 1991; Robbins and Cobb, 1992; Robbins et al., 1993). Phosphorylation of ERK2 by MEKs releases it from MEKs and the activated ERK2 either translocates into the nucleus or remains in the cytoplasm in association with various scaffold proteins or substrates.

Activated ERK2 executes its role in the signaling cascade by phosphorylating various downstream substrates in the cytoplasm and nucleus. ERK2 displays a high preference of specificity in its phosphorylation site with Ser/Thr-Pro motif (Canagarajah et al., 1997). But, the Ser/Thr-Pro motif alone, which is common in many protein substrates, cannot account for the high substrate specificity of ERK2. To compensate for the low affinity of phosphorylation consensus sequence, MAPKs employ various docking interactions in substrate recognition (Abramczyk et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011b). In this mechanism, the phosphorylation consensus motif is drawn into close proximity with the catalytic site of MAPKs through various recognition sites remote from the catalytic site of ERK2 (Rainey et al., 2005). The best-characterized docking sites of ERK2 are the D-recruitment site (DRS) and the F-recruitment site (FRS). They respond to D-binding motif and F-binding motif, respectively, in recognition of the downstream substrate or upstream regulators (Lee et al., 2011a).

In resting cells, unphosphorylated ERK2 stays primarily in the cytoplasm, and is associated with several anchoring proteins. The localization and duration of localization are determined by several factors, including the nature of the extracellular stimuli and the integration of temporal- and spatial-specific proteinprotein interactions (Caunt et al., 2008; Coles and Shaw, 2002). Phosphorylation releases ERK2 from its cytoplasmic counterparts and it either translocates into the nucleus or stays in the cytoplasm by associating with various scaffold proteins or cytoplasmic substrates. Of the approximately 160 ERK2 substrates that have been identified so far, approximately 70 are cytoplasmic (Yoon and Seger, 2006). Although the mechanism and identity of the nuclear anchoring counterparts have not been clearly solved yet, stimulus-dependent duration of ERK2 localization in the nucleus suggests an existence of nucleus anchoring proteins or other nucleus-retention mechanism or involvement of scaffold proteins in substrate selectivity (Lenormand et al., 1998; Mandl et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2000; Reiser et al., 1999; Tanimura et al., 2002). Transient or sustained accumulation of ERK is also responsible for the difference between quiescence and proliferation in fibroblasts and epithelial cells (Pages et al., 1993; Vantaggiato et al., 2006; Yujiri et al., 2000). Sustained ERK2 activation in fibroblasts induces the expression of nuclear proteins that mediate the dephosphorylation and scaffolding of ERK, resulting in its accumulation in the nucleus. So, the localization and retention time of the activated MAPK in specific compartment are determined by various factors including the concentrations of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK2, various anchoring proteins in cytoplasm and nucleus and the equilibrium among them (Rosseland et al., 2005; Samarakoon and Higgins, 2003; Skarpen et al., 2008). The concentrations of MEKs and ERKs show cell-type specificities and the duration and strength of extracellular stimuli determines the concentration of released (phosphorylated) ERK2, and might also affect the synthesis of stimulus-dependent nuclear anchoring protein.

IN VITRO ANALYSIS OF ERK2 MONOMER AND DIMER MODELS

ERK2 structure

ERK2 is a compact 42 kDa protein. The N-terminal domain (residues 1–109 and 320–358) is composed of β-strands (β1–β4) and two α-helices (Canagarajah et al., 1997). The C-terminal domain (residues 110–319) is mostly helical and contains an activation loop and catalytic sites. Phosphorylation at Thr183 and Tyr185 of the activation loop (Asp165-Glu195) triggers a large conformational change in ERK2, opening the P+1 binding pocket. Several binding sites in ERK2 that interact with various substrates and upstream regulators have been identified. The D-recruiting site, comprised of β7, β8 and αD helix, and part of loops 7–8, is distant from the catalytic site and contains a common docking domain (Asp316 and Asp319) and hydrophobic binding cleft. The D-binding motif, consensus sequence of (R/K)n-X2-6-Φ-X-Φ, is commonly found in many ERK2 substrates, MEKs and MAPK phosphatase, interacting with the D-recruiting site of ERK2. DEF motif (docking site for ERK, or F binding motif) is identified in ERK2 nuclear substrates and has a characteristic FXFP consensus docking domain. The DEF docking site in ERK2 is closed in the inactive state and is accessible only in the active state. Part of the activation loop (Phe181-Thr204), αG helix and α2L14 of the MAPK kinase insert constitute the F-binding site for the DEF-motif. These sites, potentially operating together with additional domains in ERK2 such as the MAPK insert, are responsible for the levels of ERK2 phosphorylation as well as subcellular localization.

The putative dimeric structure of activated histidine (His)-tagged Erk2 was suggested in that dimeric interface is formed from a nonhelical leucine zipper composed of L333, L336 and L334 from each monomer (Canagarajah et al., 1997; Wilsbacher et al., 2006). Three residues at the C-terminus (Y356-S358) bind in the active site of a neighboring molecule, where R357 in the C-terminus makes an ion pair with D165 in the active site of another molecule. The X-ray structure also indicates the presence of two ion pairs on each end of the interface, H176 from the activation loop and L343 from the C terminus. Participation of H176 in activation loop might partly explain the decrease in the dissociation constant of phosphorylated Erk2.

Reports on dimeric or monomeric phosphorylated ERK2 in vitro

Despite the possibility that dimerization could be involved in diverse regulation mechanisms in the ERK2 signal propagation cascade, a few in vitro studies on the monomer-dimer equilibrium have been undertaken with biophysical/bioanalytical characterization. And even these studies have reported contradictory results concerning dimerization. The dimer dissociation constant (KD) of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated His6-tagged ERK2 in vitro were determined to be 7.5 nM and 20 μM, respectively, by monitoring gel filtration and equilibrium sedimentation studies (Khokhlatchev et al., 1998). Based on the reported dimeric interface, a dimerization-impaired ERK2 mutant (H176E, L333,336,341,344A) was also constructed (Wilsbacher et al., 2006). Interestingly, gel filtration chromatograms in this study showed that the relative dimer-to-monomer ratio depended on the existence of divalent cations, such as Ca2+ or Mg2+. Furthermore, incubation with strong divalent cation chelators, like EDTA and EGTA, diverted the equilibrium exclusively to the monomer form. Dimeric interface formation was also suggested in a hydrogen exchange/mass spectroscopy study of phosphorylated His-tagged ERK2 (Hoofnagle et al., 2001). The residues comprising the putative dimeric interface of phosphorylated ERK2 were more protected in solvent exchange than the interface of unphosphorylated ERK2.

Contrary to the reports on dimerization of active ERK2, Callaway et al. (2006) reported that active His6-tagged ERK2 exists predominantly as a monomer by employing gel filtration chromatography coupled with multi-angle laser light scattering. The elution profile of the gel filtration column exhibited several peaks, but molar mass distribution obtained from light scattering experiments demonstrated little deviation from approximately 41 kDa. Although the authors also suggested the existence of a dimeric association of ERK2, its quantity was vanishingly small and negligible. A more thorough biophysical investigation on the monomer-dimer equilibrium of activated ERK2 was recently carried out by employing various experimental tools including light scattering, analytical ultracentrifuge and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Kaoud et al., 2011). All the experimental results in this study indicated that tagless active ERK2 was a monomer and there was no propensity of homodimeric association. Comparison of His6-tagged and tagless ERK2 demonstrated that His6-tag on ERK2 induced significant dimerization in the absence of added divalent cations and dimeric His6-tagged ERK2 was estimated to be about 30%. Whereas tagless ERK2 showed no dependency on divalent cations for its monomer-dimer equilibrium, His-tagged ERK2 displayed that added Mg2+ led to increased dimeric population.

The reason of the discrepancy of the observed ERK2 monomer/dimerization equilibrium is not clear. One possibility that we must take heed of is the method of ERK2 expression and purification. In some of the aforementioned experiments, the Histidine tag was employed for purification purposes. His-tags have been generally used with great efficiency in protein expression with the belief that its presence does not affect the biochemical properties of proteins. But, in several reports, the His-tag did affect biophysical/biochemical properties and has the propensity to promote protein dimerization/oligomerization (Amor-Mahjoub et al., 2006; Wu and Filutowicz, 1999). It is interesting to note that removal of the His-tag from Ets-1, one of well-defined ERK2 substrate in the nucleus, decreases its binding affinity to ERK2 by 1.5-fold (Kaoud et al., 2011). The influence of His-tag on ERK2 dimerization was also found in other studies in relation with divalent cations. For example, calcium concentration played a critical role in nuclear translocation with His6-tagged ERK2, with calcium chelator enhancing nuclear translocation, whereas calcium ionophores prevented it (Chuderland et al., 2008). A study with His-tagged ERK2, monomer/dimer equilibrium in vitro was strongly dependent on the divalent cation concentration (Wilsbacher et al., 2006). Divalent ion increased the dimer population, while chelators decreased it. So, the enhanced nuclear translocation upon calcium chelator may imply the monomeric nature of ERK2 nuclear translocation or the simple diffusion is more efficient than the active transport.

Issues with dimer mutants

ERK2 mutant with impaired dimerization capability has been constructed according to the X-ray crystal structure of the putative ERK2 dimer (Wilsbacher et al., 2006), usually alanine mutations on four leucine residues, L333,336,334,343 and glutamate replacement for H176. Most nuclear transport study with the dimer-impaired mutant was performed by either deletion or mutations on these five residues. Although there has not been any report on the effect of these mutations on ERK2 structural characteristic, they might affect the folding and/or ERK2-substrate interaction properties. Especially, H176 is located in the activation loop and comprises part of the F-recruiting site of active ERK2. A coimmunoprecipitation study of dimerization-deficient ERK2 with endogeneous MEK1 (Wolf et al., 2001) showed that the residues reported to be required in homo-dimerization of ERK2 (H176, L333, L336, L341 and L344) are important in the association of ERK2 with MEK1 and also in nuclear translocation.

ERK2 IN THE CYTOPLASM

Regulation of ERK2 signal propagation through spatial sequestration is considered to be one of the major control mechanisms and, in association with scaffold proteins, accounts for activation of many cytoplasmic substrates. In un-stimulated cells, ERK2 stays mainly in the cytoplasm. Several reported proteins and organelles are responsible for ERK2 cytoplasmic retention, including microtubules, MEKs, protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-SL and various scaffold proteins, such as kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR), similar expression to fgf genes (Sef), PEA-15 and IQGAP-1. MEK, which has nuclear export signal (NES) (Adachi et al., 2000), can serve as cytoplasmic anchors for ERK2 by a direct binding interaction, holding the ERKs in the cytoplasm at times when the signaling pathway is inactive (Burack and Shaw, 2005). Among the many scaffold proteins for ERK2 identified to be necessary for localization into the cytoplasm, several are reported to form a dimer in association with ERK2. (Casar et al., 2008) reported that KSR1 binds to the ERK2 dimer via the FXF motif and that dimerized ERK2 is required in cytoplasmic substrate cPLA2 activation. As the FXF motif is also engaged in KSR1 binding and disruption of ERK2 dimerization impaired its binding capability to KSR1, the authors suggested that each respective monomer of dimerized ERK2 binds KSR1 and cPLA2 concomittently. Sef, IQGAP1, MP-1 (MEK partner 1) and MORG (MAPK organizer) were also found to associate with dimeric ERK2 upon EGF stimulation. Interestingly, the authors found that dimer formation of ERK2 was initiated by the association of monomeric ERK2 with a prebound ERK2-scaffold complex. But, dimeric interaction of ERK2 with scaffold proteins are not universal and, for example, PEA-15 was found to bind to monomeric ERK2 (Kaoud et al., 2011). So far, there has not been any observation that scaffold proteins and ERK2 dimerization are required in the activation of nuclear substrates.

MEK1/2

In resting cells, inactive ERK2 binds directly to MEKs (Fukuda et al., 1997) or with the help of other scaffold proteins (Morrison and Davis, 2003) via several protein-protein interaction motifs in each of the proteins. Several distinct sites in ERK2 have been identified in MEK interactions, include common docking (CD) domain in the C-terminus (Rubinfeld et al., 1999; Tanoue et al., 2000), N-terminal domain (Eblen et al., 2001), amino acids 312–320 (Rubinfeld et al., 1999; Wolf et al., 2001), MAPK insert (residues 246–276) and other C-terminal residues (Robinson et al., 2002; Rubinfeld et al., 1999). As a counterpart to the CD-domain in ERK2, the N-terminal region of MEK (residues 1–32) was found to participate in ERK2 binding and was aligned in tandem with nuclear export signal sequence (residues 33–44) (Fukuda et al., 1997). So, the peptide encompassing the ERK2 biding site and the NES sequence was demonstrated to be sufficient for ERK2 localization in cytoplasm (Fukuda et al., 1997). Several point mutations that impaired MEK-ERK2 binding while retaining other substrate binding affinity led to constitutive localization of ERK2 in nucleus, even in the presence of overexpressed MEK1 (Robinson et al., 2002). Active ERK2 is dissociated from MEK upon phosphorylation at T183 and Y185 in the activation loop. Dissociation allows both proteins to translocate into the nucleus separately. But, whereas ERK2 could remain in nucleus for up to several hours (Pouyssegur et al., 2002), the nuclear export signal of MEK in its N-terminal region enforces its export to the cytosol (Fukuda et al., 1996; Jaaro et al., 1997). When CHO cells were transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-ERK2 plasmid, the overexpressed GFPERK2 was distributed both in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Whitehurst et al., 2004). But, when co-transfected with a 2:1 ratio of MEK:GFP-ERK2, ERK2 was localized only to the cytoplasm. Skarpen et al. (2008) suggested the MEK-dependent regulation of ERK2 compartmentalization. The authors proposed that MEK1-activated ERK2 accumulated in the nucleus, while the MEK2-activated ERK2 remained in the cytoplasm. Adachi et al. (2000) suggested that relocalization of nuclear MAPK to the cytoplasm was achieved by nuclear export with MEK1. Thus, MEK1 is assumed to function, not only as a cytoplasmic anchor of MAPK, but also a continuous shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

PTP-SL

ERK2 is also retained in cytoplasm in an inactive form by association with protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-SL through the kinase interaction motif (Blanco-Aparicio et al., 1999). Phosphorylation of PTP-SL by protein kinase A releases ERK2 from this association.

KSR

KSR is constitutively associated with MEK, providing a platform for Raf or ERK binding (Cacace et al., 1999; Muller et al., 2001). In response to growth factor stimulation, KSR translocates from cytoplasm to the plasma membrane, facilitating MAPK signaling. In a study of KSR1-null mouse embryo fibroblasts, abrogation of the KSR-mediated Raf/MEK/ERK cascade could enhance cell immortalization (Kortum et al., 2006). Casar et al. reported the involvement of KSR in localization-directive ERK activation (Casar et al., 2009). The authors showed that, while human ERKs activated in lipid rafts interact with KSR1 phosphorylating EGF receptor, those activated at the endoplasmic reticulum associate with IQGAP-1, a phosphorylating cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2).

Sef

Sef (hSef) associates specifically with the active form of MEK (Torii et al., 2004). hSef binds MEK/ERK complex, inhibiting the dissociation and nuclear translocation of activated ERK from MEK, while it does not intimidate its cytoplasmic activity. ERK activated at endoplasmic reticulum requires Sef-1 in cPLA2 activation.

PEA-15

PEA-15 is a multifunctional protein that is expressed in various cell types and is enriched in brain astrocytes. It has been reported to be involved in apotosis and resistance to insulin in type II diabetes (Condorelli et al., 1999; Kitsberg et al., 1999). PEA-15 was also observed to be a mediator of cytoplasmic sequestration of ERK2 (Formstecher et al., 2001). Due to its nuclear export sequence, it blocks ERK accumulation in the nucleus while keeping cytoplasmic activity of ERK intact. In ERK2 binding, it requires MAPK insert in ERK2 (Whitehurst et al., 2004) and as a MAPK insert is necessary in MEK1 binding, PEA-15 binding was found to block activation of ERK2. A recent light scattering analysis (Kaoud et al., 2011) of active/tagless ERK2/PEA-15 complex following fractionation with a size-exclusion column showed that ERK2 forms a strong 1:1 complex with PEA-15 of approximately 57 kDa, suggesting that ERK2 binds PEA-15 as a monomer.

ERK2 IN THE NUCLEUS

Nuclear substrates of ERK2

Whether ERK2 exists as a monomer or dimer in the nucleus has not been resolved. One clue to answering this question could be the nuclear substrates of ERK2. If these substrates predominantly exist as a dimer, then the dimeric form of ERK2 in the nucleus could also be inferred. Many transcriptional factors form a homo-dimer or hetero-oligomeric structure in DNA binding through recognition of a palindromic DNA-sequence motif (Lee, 1992). So far, about 50 nuclear substrates of ERK2 have been found and most are transcriptional factors (Yoon and Seger, 2006). Ets family members, including Ets-1 and Elk1, Smad proteins, c-Fos, c-Myc and ATF2 are the most extensively studied substrates of ERK2. They constitute the final tier of ERK2 signaling cascade by regulating various transcriptions upon phosphorylation by active ERK2.

DNA binding structures of several Ets family members have been resolved, showing that a dimeric or hetero-oligomeric complex is formed upon DNA binding. But, homo-dimerization of Ets-1 is mediated by specific arrangement of DNA (Lamber et al., 2008) and monomeric Ets-1 can also bind a single Ets-binding domain in the absence of the palindromic sequence (Pufall and Graves, 2002; Sharrocks, 2001; Wasylyk et al., 1991). An in vitro study of the ERK2-Ets-1 complex suggested that Ets-1 exists as a monomer and that an additional cofactor might be necessary for dimerization (Callaway et al., 2006). Crystallographic structures of Elk-1 and Sap-1, Ets family members and ERK2 substrates revealed that they bind to DNA as a monomer utilizing a single Ets-DNA binding motif (Mo et al., 2000). In vitro analysis of cell lysates showed that active Elk-1 mainly exists as a monomer and the observed higher molecular weight of oligomerized Elk-1 than the calculated one suggests that a cofactor may be needed for oligomerization (Drewett et al., 2000). A recent study suggested that Elk-1 exists as a dimer in the cytoplasm but as a monomer in the nucleus (Evans et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011b). The authors proposed that the mutual exclusiveness of Elk-1 Ets-binding domain for the dimeric interface and DNA binding leads to monomeric accumulation in the nucleus. C-Jun and c-Fos, components of the AP1 transcription factor, heterodimerize with each other and bind to a specific DNA sequence upon activation by ERK2 (Patel et al., 1994; Seldeen et al., 2008). Smad proteins also oligomerize upon activation. Phosphorylation of R-Smads (Smad1, Smad2, and Smad3) at their respective three serine residues in the C-terminus by TGFβ receptor kinase triggers their heterotrimerization (two R-Smad + one Smad4) with Smad4 (Baburajendran et al., 2011; Chacko et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001). TGFβ-induced activation of Smad1/2/3 leads to nuclear accumulation of the heteromer, which activates target genes. But, Smad1/2/3 are also substrates of ERK2 and Ras-induced activation inhibits TGFβ signaling by phosphorylating remote threonine residue by ERK2 (Kretzschmar et al., 1997; 1999). Inactive Smad3 exhibits monomer-homotrimer equilibrium with an overall trimerization constant K3 of approximately 3 × 109 M−1 (Correia et al., 2001), suggesting that the homotrimer is predominant. Fitting the sedimentation equilibrium incorporating homodimer model yields negligible components for dimer population and phosphorylation at three C-terminal serine residues enhances the ability to form a trimer by 17–35 fold. Myc is relatively unstructured as a monomer and its α-helices are properly folded only when its dimerization interfaces are properly aligned upon DNA binding (Banerjee et al., 2006; Kohler et al., 1999). Moreover, it forms a stable heterodimer complex with another transcription factor, Max, and these proteins use a monomer pathway in which a monomer bound to DNA induces the other partner to dimerize on the DNA surface (Kohler et al., 1999). The homodimer dissociation constant for Myc was calculated to be approximately 7 mM (Jung et al., 2005), indicating a strong propensity of Myc to form a monomer instead of a dimer.

Nuclear anchoring proteins

Lenormand et al. suggested that the driving force of nuclear translocation of ERK2 is a neosynthesis of short-lived nuclear anchoring proteins (Lenormand et al., 1993). The authors found that, while inhibitors of protein synthesis impede the nuclear accumulation of ERK1/2, the stabilization of the presumed short-lived proteins by inhibition of targeted proteolysis promotes it. While nerve growth factor produces prolonged ERK2 activation up to 2 h, epidermal growth factor can activate ERK2 only transiently. Caunt et al. reported that ERK2 activation responses to epidermal growth factor (EGF) and protein kinase C (PKC) are transient and sustained, respectively, in its duration of effect (Caunt et al., 2008). ERK2 activation was reported to show stimulus-specific in nuclear localization. Whereas PKC-activated ERK2 is anchored to dual specificity phosphatease 2 or −4 in dephosphorylated form in nucleus, activated EGF showed only transient accumulation in nucleus and then was translocated back into the cytoplasm.

Nuclear translocation mechanisms

Another clue to resolve whether ERK2 exists as a monomer or a dimer lies in the transport mechanism of ERK2 into nucleus.

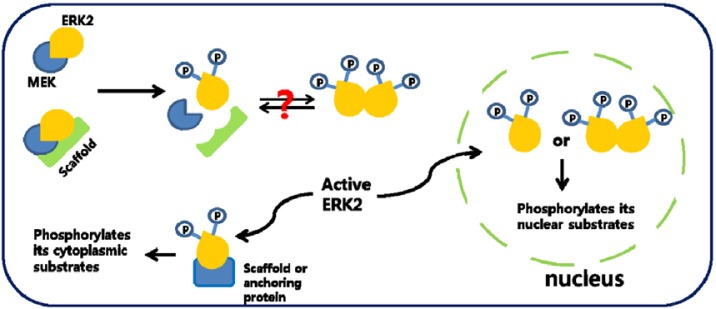

Active transport

Active transport mechanism of dimerized ERK2, which is too big to translocate into the nucleus by simple diffusion, was first proposed by observing nuclear uptake of unphosphorylated ERK2 by phosphorylated one. After microinjection into the cytoplasm, phosphorylation-site mutated (T183A, Y185F) ERK2 translocates into the nucleus after stimulation of cells (Khokhlatchev et al., 1998). Coinjection of unphosphorylated ERK2 with thiophosphorylated kinase-defective one suggested that phosphorylated ERK2 forms an import-competent complex with the unphosphophorylated one. Dimer formation was also surmised by observing nuclear translocation of β-gal-MAPK, which is supposed to be too big for passive diffusion, upon stimulation (Adachi et al., 1999). Whereas β-gal-tagged ERK2 could translocate into nucleus, dimerization-impaired (H181E L4A) one did not enter the nucleus. Reduction of nuclear translocation of GFP-tagged ERK2 with the deletion of amino acids 174–177 was also suggested as proof of the requisite for ERK2 dimerization in translocation (Horgan and Stork, 2003). But the assumption of dimer formation in these studies was based on the idea that either only phosphorylated ERK2 can translocate into nucleus, which has been proved false in many studies (Burack and Shaw, 2005; Fujioka et al., 2006; Lidke et al.; Whitehurst et al., 2002; Wolf et al., 2001) since then, or that the mutation/ deletion of amino acid residues (H176, L333, L336, L341 and L344) does not affect capability in protein-protein interaction, which was also questioned in many studies (Radhakrishnan et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2001; Yazicioglu et al., 2007). And injection of extraneous ERK2 might disturb the equilibrium among the various scaffold and anchoring proteins and endogeneous phosphorylated- and unphosphorylated-ERK2. The concentrations of endogeneous ERK and MEK show cell-type dependent variation [see the references in (Fujioka et al., 2006)] and both are in the range of sub- to a few micromolar range. Considering the fact that the subcellular redistribution of ERK is an outcome of re-equilibration of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERKs toward various anchoring-protein counterparts upon stimulation, injection of 20–80 μM of extraneous ERK could result in erroneous interpretation.

Facilitated diffusion via nuclear pore complex (NPC)

NPCs are large proteinaceous structures that serving as the gatekeepers controlling nucleocytoplasmic exchange of protein and RNA [see references in reviews (Chatel and Fahrenkrog, 2011; Wente, 2000)]. A NPC is built from nucleoporins and single or multiple copies of eight nucleoporins typically constitute the complex. So far, about 30 nucleoporins have been identified and in most cases nucleocytoplasmic transport through NPCs occurs through the binding of nuclear transport receptors of importins and exportins to a phenylalanine-glycine repeat motif in nucleoporins. This represents a facilitated diffusion mechanism, which requires specific, low affinity interactions with nucleoporin. A passive diffusion mechanism mediated through NPC was first proposed after the finding of energy-independent translocation of GFP-fused ERK2, which is too large to passively pass through the nuclear pore by passive diffusion. With reconstituted digitonin-permeabilized cells, it was suggested (Matsubayashi et al., 2001) that GFP-fused ERK2 can pass through the nuclear pore by directly interacting with NPC irrespective of its phosphorylation state. The authors showed that wheat germ agglutinin, which binds to glycosylated nucleoporin and inhibits the NPC-mediated transport, could markedly delay the translocation of GFP-ERK2. ERK2 was found to directly bind to phenylalanine-glycine repeat region of nucleoporin Nup214 in vitro. The same conclusion was reached independently using nearly the same experimental design (Whitehurst et al., 2002), except that they identified Nup153 as a binding partner for ERK2. In their study, GFP-ERK2 could accumulate in the nucleus irrespective of its phosphorylation state, implying the lack of requirement of phosphorylation-dependent dimerization in this translocation mechanism. Another experiment with GFP-ERK2 in a nuclear translocation study showed that dimerization-impaired ERK2 could still translocate into the nucleus upon stimulation (Wolf et al., 2001), indicating the monomeric nature of ERK2 in the NPC complex. Yazicioglu et al. (2007) suggested that the FXF motif in nucleoporin 153 may be involved in ERK2 binding in nuclear transportation. The authors found that mutations near the F-binding site in ERK2 reduced the binding to a recombinant C-terminal fragment of nucleoporin 153.

High rate of diffusion

Fujioka et al. (2006) investigated the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling rate of ERK by monitoring fluorescent intensity change in a short time scale. Based on the observed kinetic parameters, the authors developed a simple kinetic simulation model of the ERK cascade. They found that the rates of nuclear import or export of ERK did not show phosphorylation dependency. Utilizing these experimental parameters, Radhakrishnan et al. (2009) simulated cytosol-to-nucleus translocation by compartmental computational sensitivity analysis model (Radhakrishnan et al., 2009). Although this computational analysis did not include dimeric model in the simulation, the authors produced a theoretical profile that fit excellently with the experimental results, demonstrating that nuclear entry of wild type ERK2 and mutant one could be explained without invoking the dimerization hypothesis. From the simulation data, the authors suggested that altered interaction of dimerization-impaired ERK2 with phosphorylated MEK can lead to delayed nuclear uptake. Live cell imaging experiment of yellow fluorescent protein-fused ERK2 (Burack and Shaw, 2005) showed that the steady state rate of ERK2 migration into the nucleus was ATP-independent in resting cells and that this rate was much faster than the rate in EGF-stimulated ERK2, suggesting that passive diffusion is largely responsible for ERK2 migration. In the same study, the rate of nuclear translocation of dimerization-impaired ERK2 mutant stimulated by EGF was the same as that of wild-type ERK2, indicating that dimerization of ERK2 is not required for nuclear entry. But, as the characteristics or even existence of nucleus-anchoring protein has not been conclusively confirmed, we have no clue on the influence of protein modification on its nucleus localization. Adachi et al. (1999) showed that an inhibitor of nuclear pore-mediated active transport or an inhibitor of active nuclear transport were incapable of blocking the nuclear entry of ERK2, suggesting that ERK2 can passively diffuse into the nucleus.

MISCELLANEOUS EVIDENCE

Dimerization upon phosphorylation was also studied in vivo using a bioluminescence indicator (Kaihara and Umezawa, 2008). Genetically encoded tandem array of ERK2 were linked in the N- and C-termini with the N- and C-terminal halves of split Renilla luciferase. Stimulation of MCF-7 cells with epidermal growth factor increased the luciferase bioluminescence as each half of luciferase located at N- and C-termini of the tandem array of ERK2 was brought into close proximity due to the dimerization of ERK2. But, the irreversible connection of fused ERK2 does not truly reflect a dynamic physiological condition.

The observations of dimer formation of other MAPKs, including P38, ERK1 and JNK, were considered to be other grounds to support the dimeric nature of ERK2. Especially, ERK1, which shares approximately 70% sequence identity with ERK2, has been supposed to form a homodimer. Philipova and Whitaker reported that phosphorylated ERK1 forms a homodimer in vivo and in vitro, and that dimerization enhances ERK1 activity by 20-fold compared with the phosphorylated monomer (Philipova and Whitaker, 2005). The authors suggested that phosphorylated ERK1 could also form a dimer with unphosphorylated ERK1, although its activity increase was not as large as that of the phosphorylated dimer. Peak ERK1 activity was achieved by the phosphorylated dimer and basal activity in vivo is maintained by homodimers formed of monophosphodimer. But unfortunately, the authors used a non-reducing condition in sample preparation and addition of β-mercaptoethanol clearly disintegrated the oligomerized ERK1. Interestingly, in the same study, monomerized active ERK1 formed a high-molecular weight complex upon treatment with cell extract, implying that cytoplasmic cofactors are needed in ERK dimerization. Phosphorylated P38 does not form a homodimer (Bellon et al., 1999), but it was suggested that phosphorylated P38α/-β isoforms complex with ERK1 and ERK2 inhibiting MAPK activation (Casar et al., 2007).

Using GFP-tagged ERK1, Lidke et al. (2009) observed that dimerization is not a requisite for nuclear translocation and a putative dimerization-mutant ERK1 accumulates at the same level in the nucleus as that of wild type ERK1. Furthermore, the authors could not find any evidence of ERK1 dimerization upon stimulation in fluorescence resonance energy transfer and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measurements. The authors suggested that dimerization-mutation in ERK1 might affect its affinity toward scaffold proteins, thereby decreasing its activation efficiency by MEK.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the crystallographic studies of ERK2 decades ago, the dimer model of active ERK2 was evoked to explain many in vitro and in vivo observations, and active nuclear transport mechanism of dimeric ERK2 was suggested as one of the major processes of nuclear entry. But, many contradicting observations questioning the ERK2 dimer model compelled the inevitable reappraisal of the validity of this model. Especially, the thorough biophysical investigation of active ERK2 (Kaoud et al., 2011) significantly undermined the validity of the dimer hypothesis of active ERK2. According to the latter result, the effect of his-tag and the method of purification on ERK2 dimerization should be re-evaluated in the interpretation of experimental result. The active transport mechanism of dimeric ERK2 was also disputed when considering that the nuclear pore complex might be involved in the passive diffusion of labeled bulky ERK2. Mostly monomeric state of nuclear substrates of ERK2 also favors the monomer model of ERK2. There were several reports on dimer-to-dimer interaction of ERK2 with its cytoplasmic scaffold proteins. But, scaffold protein-induced dimerization of ERK2 was also suggested be a plausible explanation. Despite all these disputable experimental results on ERK2 monomer and/or dimer models, determining decisively whether active ERK2 exists as a monomer or dimer still demands more thorough investigations on this question.

Fig. 1.

Schematic description of ERK2 localization inside cells. Unphosphorylated, inactive ERK2 stays in cytoplasm via association with various anchoring or scaffolding proteins including MEKs, PTP-SL, KSR, and so on. Phosphorylated, active ERK2 either translocates into nucleus, activating its nuclear substrates, or stays in cytoplasm through interaction with various scaffolding or anchoring proteins.

Fig. 2.

Schematic description of the suggested translocation mechanism for active ERK2 into nucleus. (A) Simple diffusion for monomeric active ERK2. (B) Spontaneous active transport mechanism for explaining nuclear translocation of bulky dimeric ERK2. (C) Facilitated diffusion mechanism via nuclear pore complex for explaining bulky GFP-fused ERK2 in energy-independent pathway.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Core Research Center (grant R15-2006-020-00000-0 to Y.S.B), by World Class University program (R31-2008-000-10010-0 to Y.S.B) of the Ministry of Education, Science, and RP-Grant 2011 of Ewha Womans University.

REFERENCES

- Abramczyk O., Rainey M.A., Barnes R., Martin L., Dalby K.N. Expanding the repertoire of an ERK2 recruitment site: cysteine footprinting identifies the D-recruitment site as a mediator of Ets-1 binding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9174–9186. doi: 10.1021/bi7002058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M., Fukuda M., Nishida E. Two co-existing mechanisms for nuclear import of MAP kinase passive diffusion of a monomer and active transport of a dimer. EMBO J. 1999;18:5347–5358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M., Fukuda M., Nishida E. Nuclear export of MAP kinase (ERK) involves a MAP kinase kinase (MEK)-dependent active transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:849–856. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor-Mahjoub M., Suppini J.P., Gomez-Vrielyunck N., Ladjimi M. The effect of the hexahistidine-tag in the oligomerization of HSC70 constructs. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2006;844:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburajendran N., Jauch R., Tan C.Y., Narasimhan K., Kolatkar P.R. Structural basis for the cooperative DNA recognition by Smad4 MH1 dimers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8213–8222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Hu J., Goss D.J. Thermodynamics of protein-protein interactions of cMyc, Max, and Mad: effect of polyions on protein dimerization. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2333–2338. doi: 10.1021/bi0522551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon S., Fitzgibbon M.J., Fox T., Hsiao H.M., Wilson K.P. The structure of phosphorylated p38gamma is monomeric and reveals a conserved activation-loop conformation. Structure. 1999;7:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Aparicio C., Torres J., Pulido R. A novel regulatory mechanism of MAP kinases activation and nuclear translocation mediated by PKA and the PTP-SL tyrosine phosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1129–1136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burack W.R., Shaw A.S. Live Cell Imaging of ERK and MEK simple binding equilibrium explains the regulated nucleocytoplasmic distribution of ERK. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3832–3837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacace A.M., Michaud N.R., Therrien M., Mathes K., Copeland T., Rubin G.M., Morrison D.K. Identification of constitutive and ras-inducible phosphorylation sites of KSR: implications for 14-3-3 binding, mitogen-activated protein kinase binding and KSR overexpression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:229–240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway K.A., Rainey M.A., Riggs A.F., Abramczyk O., Dalby K.N. Properties and regulation of a transiently assembled ERK2.Ets-1 signaling complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13719–13733. doi: 10.1021/bi0610451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah B.J., Khokhlatchev A., Cobb M.H., Goldsmith E.J. Activation mechanism of the MAP kinase ERK2 by dual phosphorylation. Cell. 1997;90:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casar B., Sanz-Moreno V., Yazicioglu M.N., Rodriguez J., Berciano M.T., Lafarga M., Cobb M.H., Crespo P. Mxi2 promotes stimulus-independent ERK nuclear translocation. EMBO J. 2007;26:635–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casar B., Pinto A., Crespo P. Essential role of ERK dimers in the activation of cytoplasmic but not nuclear substrates by ERK-scaffold complexes. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casar B., Arozarena I., Sanz-Moreno V., Pinto A., Agudo-Ibanez L., Marais R., Lewis R.E., Berciano M.T., Crespo P. Ras subcellular localization defines extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 substrate specificity through distinct utilization of scaffold proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:1338–1353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caunt C.J., Rivers C.A., Conway-Campbell B.L., Norman M.R., McArdle C.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor and protein kinase C signaling to ERK2: spatiotemporal regulation of ERK2 by dual specificity phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6241–6252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706624200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko B.M., Qin B., Correia J.J., Lam S.S., de Caestecker M.P., Lin K. The L3 loop and C-terminal phosphorylation jointly define Smad protein trimerization. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:248–253. doi: 10.1038/84995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatel G., Fahrenkrog B. Nucleoporins leaving the nuclear pore complex for a successful mitosis. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary A., King W.G., Mattaliano M.D., Frost J.A., Diaz B., Morrison D.K., Cobb M.H., Marshall M.S., Brugge J.S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates Raf1 through Pak phosphorylation of serine 338. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:551–554. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuderland D., Marmor G., Shainskaya A., Seger R. Calcium-mediated interactions regulate the subcellular localization of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:11176–11188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles L.C., Shaw P.E. PAK1 primes MEK1 for phosphorylation by Raf-1 kinase during cross-cascade activation of the ERK pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:2236–2244. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli G., Vigliotta G., Cafieri A., Trencia A., Andalo P., Oriente F., Miele C., Caruso M., Formisano P., Beguinot F. PED/PEA-15: an anti-apoptotic molecule that regulates FAS/TNFR1-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:4409–4415. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia J.J., Chacko B.M., Lam S.S., Lin K. Sedimentation studies reveal a direct role of phosphorylation in Smad3:Smad4 homo- and hetero-trimerization. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1473–1482. doi: 10.1021/bi0019343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D., Vidal M., Leprince C., Liu W.Q., Cornille F., Tiraboschi G., Roques B.P., Garbay C. A Sos-derived peptidimer blocks the Ras signaling pathway by binding both Grb2 SH3 domains and displays antiproliferative activity. FASEB J. 1999;13:31–38. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derijard B., Hibi M., Wu I.H., Barrett T., Su B., Deng T., Karin M., Davis R.J. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewett V., Muller S., Goodall J., Shaw P.E. Dimer formation by ternary complex factor ELK-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:1757–1762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblen S.T., Catling A.D., Assanah M.C., Weber M.J. Biochemical and biological functions of the N-terminal, non-catalytic domain of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:249–259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.249-259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblen S.T., Slack-Davis J.K., Tarcsafalvi A., Parsons J.T., Weber M.J., Catling A.D. Mitogen-activated protein kinase feedback phosphorylation regulates MEK1 complex formation and activation during cellular adhesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:2308–2317. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2308-2317.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E.L., Saxton J., Shelton S.J., Begitt A., Holliday N.D., Hipskind R.A., Shaw P.E. Dimer formation and conformational flexibility ensure cytoplasmic stability and nuclear accumulation of Elk-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6390–6402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger G.R., Gerwins P., Widmann C., Jarpe M.B., Johnson G.L. MEKKs, GCKs, MLKs, PAKs, TAKs, and tpls: upstream regulators of the c-Jun amino-terminal kinases? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997;7:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar M.A., Tian J., Perlmutter R.M. Membrane localization of Raf assists engagement of downstream effectors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31318–31324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formstecher E., Ramos J.W., Fauquet M., Calderwood D.A., Hsieh J.C., Canton B., Nguyen X.T., Barnier J.V., Camonis J., Ginsberg M.H., et al. PEA-15 mediates cytoplasmic sequestration of ERK MAP kinase. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka A., Terai K., Itoh R.E., Aoki K., Nakamura T., Kuroda S., Nishida E., Matsuda M. Dynamics of the Ras/ERK MAPK cascade as monitored by fluorescent probes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8917–8926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M., Gotoh I., Gotoh Y., Nishida E. Cytoplasmic localization of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase directed by its NH2-terminal, leucine-rich short amino acid sequence which acts as a nuclear export signal. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20024–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M., Gotoh Y., Nishida E. Interaction of MAP kinase with MAP kinase kinase its possible role in the control of nucleocytoplasmic transport of MAP kinase. EMBO J. 1997;16:1901–1908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lee J.D., Bibbs L., Ulevitch R.J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoofnagle A.N., Resing K.A., Goldsmith E.J., Ahn N.G. Changes in protein conformational mobility upon activation of extracellular regulated protein kinase-2 as detected by hydrogen exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:956–961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan A.M., Stork P.J. Examining the mechanism of Erk nuclear translocation using green fluorescent protein. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;285:208–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro H., Rubinfeld H., Hanoch T., Seger R. Nuclear translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) in response to mitogenic stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:3742–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N., Zhang T., Fong S.L., Lim C.P., Cao X. Repression of Stat3 activity by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Oncogene. 1998;17:3157–3167. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K.C., Rhee H.S., Park C.H., Yang C.H. Determination of the dissociation constants for recombinant c-Myc, Max, and DNA complexes: the inhibitory effect of linoleic acid on the DNA-binding step. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaihara A., Umezawa Y. Genetically encoded bioluminescent indicator for ERK2 dimer in living cells. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:38–45. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaoud T.S., Devkota A.K., Harris R., Rana M.S., Abramczyk O., Warthaka M., Lee S., Girvin M.E., Riggs A.F., Dalby K.N. Activated ERK2 is a monomer in vitro with or without divalent cations and when complexed to the cytoplasmic scaffold PEA-15. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4568–4578. doi: 10.1021/bi200202y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlatchev A.V., Canagarajah B., Wilsbacher J., Robinson M., Atkinson M., Goldsmith E., Cobb M.H. Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell. 1998;93:605–615. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsberg D., Formstecher E., Fauquet M., Kubes M., Cordier J., Canton B., Pan G., Rolli M., Glowinski J., Chneiweiss H. Knock-out of the neural death effector domain protein PEA-15 demonstrates that its expression protects astrocytes from TNFalpha-induced apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8244–8251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08244.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler J.J., Metallo S.J., Schneider T.L., Schepartz A. DNA specificity enhanced by sequential binding of protein monomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11735–11739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortum R.L., Johnson H.J., Costanzo D.L., Volle D.J., Razidlo G.L., Fusello A.M., Shaw A.S., Lewis R.E. The molecular scaffold kinase suppressor of Ras 1 is a modifier of RasV12-induced and replicative senescence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:2202–2214. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2202-2214.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar M., Doody J., Massague J. Opposing BMP and EGF signalling pathways converge on the TGF-beta family mediator Smad1. Nature. 1997;389:618–622. doi: 10.1038/39348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar M., Doody J., Timokhina I., Massague J. A mechanism of repression of TGFbeta/Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M., Banerjee P., Nikolakaki E., Dai T., Rubie E.A., Ahmad M.F., Avruch J., Woodgett J.R. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamber E.P., Vanhille L., Textor L.C., Kachalova G.S., Sieweke M.H., Wilmanns M. Regulation of the transcription factor Ets-1 by DNA-mediated homo-dimerization. EMBO J. 2008;27:2006–2017. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.A. Dimeric transcription factor families: it takes two to tango but who decides on partners and the venue? J. Cell Sci. 1992;103(Pt 1):9–14. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.D., Ulevitch R.J., Han J. Primary structure of BMK1 a new mammalian map kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;213:715–724. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Warthaka M., Yan C., Kaoud T.S., Piserchio A., Ghose R., Ren P., Dalby K.N. A model of a MAPK* substrate complex in an active conformation: a computational and experimental approach. PLoS One. 2011a;6:e18594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Warthaka M., Yan C., Kaoud T.S., Ren P., Dalby K.N. Examining docking interactions on ERK2 with modular peptide substrates. Biochemistry. 2011b;50:9500–9510. doi: 10.1021/bi201103b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand P., Sardet C., Pages G., L’Allemain G., Brunet A., Pouyssegur J. Growth factors induce nuclear translocation of MAP kinases (p42mapk and p44mapk) but not of their activator MAP kinase kinase (p45mapkk) in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:1079–1088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand P., Brondello J.M., Brunet A., Pouyssegur J. Growth factor-induced p42/p44 MAPK nuclear translocation and retention requires both MAPK activation and neosynthesis of nuclear anchoring proteins. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:625–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidke D.S., Huang F., Post J.N., Rieger B., Wilsbacher J., Thomas J.L., Pouyssegur J., Jovin T.M., Lenormand P. ERK nuclear translocation is dimerization-independent but controlled by the rate of phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:3092–3102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl M., Slack D.N., Keyse S.M. Specific inactivation and nuclear anchoring of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 by the inducible dual-specificity protein phosphatase DUSP5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:1830–1845. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1830-1845.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y., Fukuda M., Nishida E. Evidence for existence of a nuclear pore complex-mediated, cytosol-independent pathway of nuclear translocation of ERK MAP kinase in permeabilized cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41755–41760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y., Vaessen B., Johnston K., Marmorstein R. Structure of the elk-1-DNA complex reveals how DNA-distal residues affect ETS domain recognition of DNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:292–297. doi: 10.1038/74055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D.K., Davis R.J. Regulation of MAP kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in mammals. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:91–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J., Ory S., Copeland T., Piwnica-Worms H., Morrison D.K. C-TAK1 regulates Ras signaling by phosphorylating the MAPK scaffold, KSR1. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson A.K., Vadhammar K., Nanberg E. Activation and protein kinase C-dependent nuclear accumulation of ERK in differentiating human neuroblastoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;256:454–467. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages G., Lenormand P., L’Allemain G., Chambard J.C., Meloche S., Pouyssegur J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases p42mapk and p44mapk are required for fibroblast proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8319–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel L.R., Curran T., Kerppola T.K. Energy transfer analysis of Fos-Jun dimerization and DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7360–7364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D.M., Rossomando A.J., Martino P., Erickson A.K., Her J.H., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D.F., Weber M.J., Sturgill T.W. Identification of the regulatory phosphorylation sites in pp42/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) EMBO J. 1991;10:885–892. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipova R., Whitaker M. Active ERK1 is dimerized in vivo: bisphosphodimers generate peak kinase activity and monophosphodimers maintain basal ERK1 activity. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:5767–5776. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouyssegur J., Volmat V., Lenormand P. Fidelity and spatio-temporal control in MAP kinase (ERKs) signalling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:755–763. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pufall M.A., Graves B.J. Autoinhibitory domains modular effectors of cellular regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002;18:421–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.031502.133614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan K., Edwards J.S., Lidke D.S., Jovin T.M., Wilson B.S., Oliver J.M. Sensitivity analysis predicts that the ERK-pMEK interaction regulates ERK nuclear translocation. IET Syst. Biol. 2009;3:329–341. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey M.A., Callaway K., Barnes R., Wilson B., Dalby K.N. Proximity-induced catalysis by the protein kinase ERK2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10494–10495. doi: 10.1021/ja052915p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser V., Ammerer G., Ruis H. Nucleocytoplasmic traffic of MAP kinases. Gene Expr. 1999;7:247–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D.J., Cobb M.H. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 2 autophosphorylates on a subset of peptides phosphorylated in intact cells in response to insulin and nerve growth factor: analysis by peptide mapping. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:299–308. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D.J., Zhen E., Owaki H., Vanderbilt C.A., Ebert D., Geppert T.D., Cobb M.H. Regulation and properties of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:5097–5106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson F.L., Whitehurst A.W., Raman M., Cobb M.H. Identification of novel point mutations in ERK2 that selectively disrupt binding to MEK1. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14844–14852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosette C., Karin M. Ultraviolet light and osmotic stress: activation of the JNK cascade through multiple growth factor and cytokine receptors. Science. 1996;274:1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseland C.M., Wierod L., Oksvold M.P., Werner H., Ostvold A.C., Thoresen G.H., Paulsen R.E., Huitfeldt H.S., Skarpen E. Cytoplasmic retention of peroxide-activated ERK provides survival in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2005;42:200–207. doi: 10.1002/hep.20762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P.P., Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:320–344. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.320-344.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld H., Hanoch T., Seger R. Identification of a cytoplasmic-retention sequence in ERK2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:30349–30352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarakoon R., Higgins P.J. Pp60c-src mediates ERK activation/nuclear localization and PAI-1 gene expression in response to cellular deformation. J. Cell Physiol. 2003;195:411–420. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa S., Ozaki Y., Fujita K., Kuroda S. Prediction and validation of the distinct dynamics of transient and sustained ERK activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:365–373. doi: 10.1038/ncb1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeberl B., Eichler-Jonsson C., Gilles E.D., Muller G. Computational modeling of the dynamics of the MAP kinase cascade activated by surface and internalized EGF receptors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nbt0402-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldeen K.L., McDonald C.B., Deegan B.J., Farooq A. Thermodynamic analysis of the heterodimerization of leucine zippers of Jun and Fos transcription factors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;375:634–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks A.D. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarpen E., Flinder L.I., Rosseland C.M., Orstavik S., Wierod L., Oksvold M.P., Skalhegg B.S., Huitfeldt H.S. MEK1 and MEK2 regulate distinct functions by sorting ERK2 to different intracellular compartments. FASEB J. 2008;22:466–476. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8650com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura S., Nomura K., Ozaki K., Tsujimoto M., Kondo T., Kohno M. Prolonged nuclear retention of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 is required for hepatocyte growth factor-induced cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28256–28264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T., Adachi M., Moriguchi T., Nishida E. A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates activators and regulators. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:110–116. doi: 10.1038/35000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii S., Kusakabe M., Yamamoto T., Maekawa M., Nishida E. Sef is a spatial regulator for Ras/MAP kinase signaling. Dev. Cell. 2004;7:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantaggiato C., Formentini I., Bondanza A., Bonini C., Naldini L., Brambilla R. ERK1 and ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinases affect Ras-dependent cell signaling differentially. J. Biol. 2006;5:14. doi: 10.1186/jbiol38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmat V., Pouyssegur J. Spatiotemporal regulation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway. Biol. Cell. 2001;93:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(01)01129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasylyk C., Gutman A., Nicholson R., Wasylyk B. The c-Ets oncoprotein activates the stromelysin promoter through the same elements as several non-nuclear oncoproteins. EMBO J. 1991;10:1127–1134. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente S.R. Gatekeepers of the nucleus. Science. 2000;288:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst A.W., Wilsbacher J.L., You Y., Luby-Phelps K., Moore M.S., Cobb M.H. ERK2 enters the nucleus by a carrier-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7496–7501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112495999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst A.W., Robinson F.L., Moore M.S., Cobb M.H. The death effector domain protein PEA-15 prevents nuclear entry of ERK2 by inhibiting required interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12840–12847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsbacher J.L., Juang Y.C., Khokhlatchev A.V., Gallagher E., Binns D., Goldsmith E.J., Cobb M.H. Characterization of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) dimers. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13175–13182. doi: 10.1021/bi061041w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf I., Rubinfeld H., Yoon S., Marmor G., Hanoch T., Seger R. Involvement of the activation loop of ERK in the detachment from cytosolic anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24490–24497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Filutowicz M. Hexahistidine (His6)-tag dependent protein dimerization a cautionary tale. Acta Biochim. Pol. 1999;46:591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.W., Hu M., Chai J., Seoane J., Huse M., Li C., Rigotti D.J., Kyin S., Muir T.W., Fairman R., et al. Crystal structure of a phosphorylated Smad2. Recognition of phosphoserine by the MH2 domain and insights on Smad function in TGF-beta signaling. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:1277–1289. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Makris C., Su B., Li E., Yang J., Nemerow G.R., Karin M. MEK kinase 1 is critically required for c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation by proinflammatory stimuli and growth factor-induced cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5243–5248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., Pallero M.A., Gupta K., Chang P., Ware M.F., Witke W., Kwiatkowski D.J., Lauffenburger D.A., Murphy-Ullrich J.E., Wells A. EGF receptor regulation of cell motility: EGF induces disassembly of focal adhesions independently of the motility-associated PLCgamma signaling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 5):615–624. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazicioglu M.N., Goad D.L., Ranganathan A., Whitehurst A.W., Goldsmith E.J., Cobb M.H. Mutations in ERK2 binding sites affect nuclear entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28759–28767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Seger R. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors. 2006;24:21–44. doi: 10.1080/02699050500284218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yujiri T., Ware M., Widmann C., Oyer R., Russell D., Chan E., Zaitsu Y., Clarke P., Tyler K., Oka Y., et al. MEK kinase 1 gene disruption alters cell migration and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase regulation but does not cause a measurable defect in NF-kappa B activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7272–7277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130176697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Wang W., Hayashi Y., Jester J.V., Birk D.E., Gao M., Liu C.Y., Kao W.W., Karin M., Xia Y. A role for MEK kinase 1 in TGF-beta/activin-induced epithelium movement and embryonic eyelid closure. EMBO J. 2003;22:4443–4454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Bao Z.Q., Dixon J.E. Components of a new human protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12665–12669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]