Abstract

The hepatitis B virus x protein (HBX) is expressed in HBV-infected liver cells and can interact with a wide range of cellular proteins. In order to understand such promiscuous behavior of HBX we expressed a truncated mini-HBX protein (named Tr-HBX) (residues 18–142) with 5 Cys→Ser mutations and characterized its structural features using circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarimetry, NMR spectroscopy as well as bioinformatics tools for predicting disorder in intrinsically unstructured proteins (IUPs). The secondary structural content of Tr-HBX from CD data suggests that Tr-HBX is only partially folded. The protein disorder prediction by IUPred reveals that the unstructured region encompasses its N-terminal ∼30 residues of Tr-HBX. A two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectrum exhibits fewer number of resonances than expected, suggesting that Tr-HBX is a hybrid type IUP where its folded C-terminal half coexists with a disordered N-terminal region. Many IUPs are known to be capable of having promiscuous interactions with a multitude of target proteins. Therefore the intrinsically disordered nature of Tr-HBX revealed in this study provides a partial structural basis for the promiscuous structure-function behavior of HBX.

Keywords: circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarimetry, hepatitis B virus-X (HBX), intrinsically unstructured/unfolded protein (IUP), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, promiscuity, truncated mini-HBX (Tr-HBX)

INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of effective vaccines, approximately 350 million people are chronically infected with human hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide. The facts that the number of chronic HBV carriers is increasing and that chronic infection with HBV results in liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma: HCC) which shows a poor prognosis suggest that additional efforts are needed to eradicate HBV by more accurately understanding the mechanism of HBV replication. HBV is a hepadnavirus composed of a partially double-stranded DNA that contains four open-reading frames (P, PreC/C, PreS1/S2/S, X) (Chisari et al., 1989; Ganem and Varmus, 1987; Mason et al., 1982; Weiser et al., 1983). The X gene in HBV encodes a protein called HBX consisting of 154 amino acid residues, whose role in cirrhosis, liver failure, and HCC has been intensively investigated (Arbuthnot and Kew, 2001; Benhenda et al., 2009; Bui-Nguyen et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2008b; Su et al., 1998; Waris and Siddiqui, 2003).

The exact function of HBX remains unknown except for the fact that HBX is a multifunctional protein involved in gene transcription, intracellular signal transduction, cell proliferation, apoptotic cell death, and DNA repair. Any structural knowledge on this promiscuous protein would be of great value, yet there is little structural information even for some regions of HBX not to mention its entire three-dimensional structure. The full HBX contains 9 Cys residues, eight of which are putatively known to be involved in forming disulfide bonds (Gupta et al., 1995). The paucity of structural information on HBX relates to the fact that ample production of full HBX with intact disulfide bonds in a soluble form or the production of certain regions of HBX that maintains some activity of full HBX has been impossible or dauntingly difficult, essentially preventing any structural studies (Hildt et al., 1996; Rui et al., 2001; Truant et al., 1995; Urban et al., 1997). Recently, shorter recombinant constructs of HBX including a variant called truncated mini HBX (residues 18–142) (we call Tr-HBX here) were successfully produced and analyzed by CD, fluorescence, and 1-D NMR spectroscopy (de Moura et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2009; Rui et al., 2005). The Tr-HBX retained at least some activity even though it contained Ser instead of Cys residues that are needed to form disulfide bonds (de Moura et al., 2005; Rui et al., 2005), insinuating that structural characterization of this Tr-HBX should yield information that could help us to at least get a glimpse on the structure-function behavior of HBX. Interestingly, Tr-HBX appeared rather unstructured by CD in aqueous solution.

NMR spectroscopy is a powerful tool that provides detailed structural characteristics of partially folded proteins or intrinsically unstructured/unfolded proteins (IUPs) at the amino acid residue level (Chi et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2000; 2012). IUPs are peculiar proteins that are affiliated with a variety of biological functions including transcription, translation, and cell signaling as well as critical diseases such as prion diseases, amyloidgenesis, cancers, and viral infections but do not form unique three-dimensional structures under non-denaturing conditions (Chouard, 2011; Lee et al., 2012). Massive bioinformatics predictions performed over the last decade suggest that approximately one-third of the whole proteome consists of such unorthodox proteins (Dunker et al., 2000; 2008; Uversky and Dunker, 2010). Here we have studied the structural features of intrinsically unfolded Tr-HBX using CD, two-dimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy, and bioinformatics predictions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site-directed mutagenesis

The Tr-HBX has a better solubility than the native HBX since it lacks the hydrophobic amino acid residues at the N- and C-termini. In order to prepare Tr-HBX we generated a HBX construct of the adr serotype containing the amino acid residues from 18 to 142 with 5 cysteines replaced by serines. The DNA Tr-HBX fragment was amplified by PCR and subcloned to pQE30 (Qiagen) with an N-terminal His tag via BamHI and SmaI restriction sites. The mutation of cysteines to serines was achieved using site-directed mutagenesis at the amino acid residue positions of 61, 69, 78, 115, and 137 and was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression and purification of Tr-HBX

E. coli strain BL-21(DE3), transformed with Tr-HBX DNA containing pQE30 vector, was grown in an LB medium. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were then further cultivated at 20°C for 16 h, harvested by centrifugation and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) containing lysozyme (1 mg/ml). After incubation on ice for 30 min, cells were lysed. Genomic DNA was digested by the addition of DNAse (5 U/μl). After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, cells were sonicated using an Ultra Cell TM (Sonics and Materials) and the pellet was separated by centrifugation (24,900 × g for 25 min at 4°C). The pellet was resuspended in the washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 3 M Urea, 1% Triton X-100) and then was solubilized in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and 8 M urea.

Protein sample preparation

The protein existing mainly in the supernatant fraction was purified using Ni-sepharose column (GE Healthcare) using an elution buffer composed of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 8 M urea, and 0.5 M imidazole. Further purification was completed by a SP-sepharose column (GE Healthcare) where the protein passed through the SP-sepharose column and was eluted by increasing the salt concentration to 1 M NaCl. The purified protein was refolded by a serial dialysis technique. For NMR experiments 15N-labeled Tr-HBX was produced whereas for CD measurements an unlabeled Tr-HBX was prepared. The molecular weight of the purified protein was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) SDS-gel electrophoresis of Tr-HBX. The molecular weight of the marker proteins (M) are indicated with lines. Lane M, molecular weight marker; lane 1, before induction; lane 2, after induction; lane 3, purified Tr-HBX. Coomassie brilliant blue was used for staining. (B) A MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of Tr-HBX.

CD spectropolarimetry

Circular dichroism (CD) experiments were performed on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter coupled to a water bath system for temperature control. Measurements in the far-ultraviolet region (210–260 nm) were carried out with a 1 mm path length quartz cell (Hellma). The protein concentration was 20 μM in a pH 6 buffered aqueous solution. Four scans were averaged for each sample and the contribution of the buffer was always subtracted. The observed optical activity was expressed as the mean residue ellipticity [θ] (degree cm2 dmol−1). CD data were processed and analyzed on Spectra manager (version 2) and Origin program (version 7).

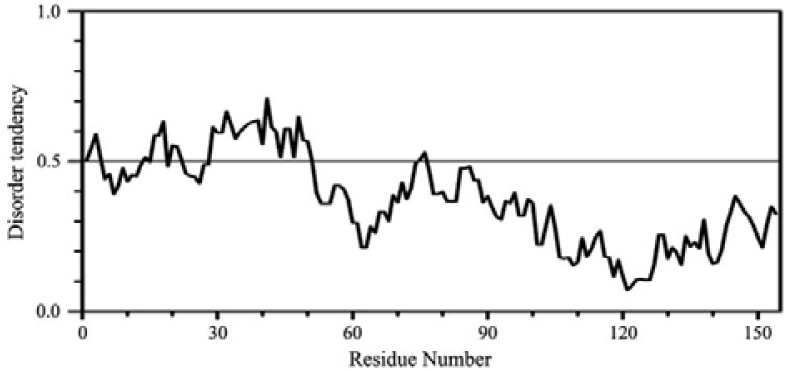

Disorder prediction of Tr-HBX

To assess the degree of overall disorder and to delineate the location of the disordered residues the amino acid sequence of Tr-HBX was input into the IUPred (http://iupred.enzim.hu) program, a web server specifically developed for predicting disorder in intrinsically unfolded proteins using estimated energy content (Dosztanyi et al., 2005). Scores above 0.5 indicate disorder and a score of 1.0 indicating a completely disordered state.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired using a Varian Unity INOVA 600 spectrometer or a Bruker DRX 900 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryo-detector. An NMR sample containing 0.36 mM 15N-labeled Tr-HBX was prepared in 90% H2O, 10% 2H2O, 25 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-ME, 1 mM PMSF and 10 μM EDTA. A two-dimensional (2-D) 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy (HSQC) spectrum was collected at 10°C. All data were processed and analyzed on a Sun SPARCstation using Varian Vnmr, nmrPipe/nmrDraw (Delaglio et al., 1995), and Sparky software (Goddard and Kneller, 2002).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Purification of Tr-HBX

The expression of Tr-HBX resulted in a band with a molecular weight of ∼15 kDa in a 17% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1). During the purification step, the protein concentration had to be kept minimal in order to avoid formation of aggregates. Initially Tr-HBX was obtained from the Ni-sepharose chromatography and then further purified by the cation exchange chromatography. The accurate mass of the Tr-HBX of the adr serotype was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Secondary structure content of Tr-HBX

A quick assessment of the secondary structure content and folding properties of Tr-HBX was done by CD at several urea concentrations (Fig. 2A). The CD spectra of Tr-HBX are typical of IUPs. Based upon the mean-residue ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222) which reflects the helical content in a protein we assessed that Tr-HBX contained less than 10% of helix and some β structures (turns and others). Interestingly, [θ]222 decreased when the urea concentration was increased (Fig. 2B). Such a denaturation profile cannot be obtained from a normal IUP, which does not contain the tertiary structure to be destroyed upon addition of urea. Therefore this result suggests that Tr-HBX should be a hybrid type IUP where a disordered region and a globular region coexist (Lee et al., 2012). Further support to this conclusion comes from a disorder prediction on HBX by the IUPred program shown in Fig. 3: the prediction shows that it is the N-terminal ∼50 residues in HBX encompassing the putative dimerization domain of HBX (Lin and Lo, 1989) or the N-terminal ∼30 residues in Tr-HBX which are disordered. Among several IUP predicting programs, PONDR, Globplot and IUPred seem to produce relatively more reliable results somewhat consistent with experimental results (Uversky and Dunker, 2010).

Fig. 2.

(A) Far-UV CD spectra of the purified Tr-HBX in 25 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-ME, 1 mM PMSF and 10 μM EDTA. ▪, 0 M ureaM ●, 1 M ureaM ▲, M M ureaM ★, 7 M urea. [B] The mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222) of Tr-HBX vs. urea concentration.

Fig. 3.

An IUPred prediction of intrinsic disorder for native HBX. The N-terminal ∼50 residues show disorder scores > 0.5.

NMR spectral analysis on Tr-HBX

Heteronuclear multidimensional (HetMulD) NMR spectroscopy assisted with a stable isotope labeling technology is a powerful technique for quantitatively investigating detailed structural features in IUPs (Lee et al., 2000; 2012). A 2-D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of a protein is used at the initial stage of structural analysis to determine if a protein might be globular or intrinsically unfolded. A protein in the latter state usually shows a very narrow chemical shift dispersion in both chemical shift dimensions of a 2-D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum (Chi et al., 2005; 2007; Kim et al., 2008a; 2009; Lee et al., 2000; 2012). Figure 4 shows a 2-D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of Tr-HBX where the chemical shift dispersion in the 1H dimension is only ∼0.6 ppm, indicating that the protein is an IUP. The 2-D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum should in principle show cross peaks the number of which is equal to the number of amino acid residues minus the number of proline residues and one (the N-terminal residue). The HSQC spectrum of Tr-HBX showing only ∼80 cross peaks instead of the expected 118 peaks indicates therefore that the Tr-HBX is not a usual IUP but a hybrid type IUP (Lee et al., 2012). The number of observable resonances in hybrid type IUPs is fewer than in non-hybrid type IUPs due to the differences in the relaxation times of the folded region and an unfolded region within one protein molecule. The number of observable peaks in several HSQC spectra obtained under various solvent conditions (different buffers, temperatures, and pH) is all similar (data not shown), indicating that the HSQC spectra showing smaller number of resonances than expected is due to the hybrid nature of Tr-HBX, not originating from experimental artifacts. This result that Tr-HBX is a hybrid type IUP is consistent with the results from CD and bioinformatics disorder prediction indicating that Tr-HBX is a hybrid IUP.

Fig. 4.

A two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of Tr-HBX in 25 mM sodium a cetate (pH 6 .0), 5 0 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, 1 mM PMSF, 0.01 mM EDTA containing 90% H2O / 10% 2H2O at 10°C.

Intrinsically unfolded nature of Tr-HBX

A native full HBX protein has never been subjected to NMR or x-ray structural characterization due to a difficulty in obtaining appropriate protein samples, either full HBX or smaller domains whose structural properties would be relevant to that of full HBX there is no indication that such a difficulty will be overcome in the near future. The current work is our first step towards a challenging goal of understanding the highly promiscuous and unorthodox structural-function behavior of HBX. Given that IUPs do not produce a single crystal suitable for an x-ray crystallographic analysis we have used NMR spectroscopy to study the structural features of Tr-HBX with Cys→Ser mutations which not only has an improved solubility but also retains some of the activity of the full HBX (Rui et al., 2005). Typical HetMuID NMR experiments require at least a few mg of protein labeled with stable isotopes such as 15N or 13C. It is currently not possible to obtain such an NMR sample. We used 15N labeled Tr-HBX in this study because it was shown that recombinant Tr-HBX at a concentration of ∼1 mM could be prepared (Rui et al., 2005), which is more or less an acceptable value for heteronuclear NMR experiments. Even though Tr-HBX is a shorter HBX construct with two disulfide bonds removed we gather that its overall topology should resemble that of full HBX to a reasonable degree judging from that it retains some activity. By the same token, we also speculate that full HBX may turn out to be a hybrid type IUP like Tr-HBX. Well-known examples of a hybrid type IUPs include prions (James et al., 1997) and p53 (Lee et al., 2000); in the former an unfolded N-terminal region consisting of ∼140 residues coexist with a globular C-terminal domain (residues 141–231) and in the latter two globular domains, a DNA binding domain (DBD) and a tetramerization domain (OD), coexist with an N-terminal intrinsically unfolded transactivation domain (∼70 residues) and a short C-terminal disordered region (residues 361–393) (Uversky et al., 2008). Since the most prominent property of IUPs is their promiscuous interaction with many target proteins the results of our combined CD, NMR, and the disorder prediction data provided a partial explanation for the promiscuous behavior of HBX.

Promiscuity of viral proteins from HBV

Several viral proteins are known to be IUPs (Longhi, 2010). For example, the preS1 surface antigen of HBV is an IUP whose NMR structural characterization led to the discovery of a potent HBV inhibitor (Chi et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008a). HBX represents a second IUP found in HBV. Thus like many other viruses HBV also appears to have adapted a strategy of using IUPs for its survival as well as for infection. The unorthodox HBX protein has been defying many attempts to study its structure-function behavior for decades. In hindsight, we learned that the current Tr-HBX construct is not a usual IUP and has structural features pertinent to the hybrid type IUPs such that Tr-HBX is not optimal for obtaining a full NMR resonance assignment needed for determining its atomic resolution structure. In addition to providing an initial insight into the promiscuity of HBX this work suggests that any future work aimed at analyzing the structural features of short regions or domains of HBX should involve a clever dissection of HBX into several (or at least two) constructs each of which would produce reasonably NMR-observable signals. One possibility is to take advantage of the fact that the sum of NMR spectra from dissected regions of a mother IUP is superimposable to the NMR spectrum of an entire mother IUP as has been demonstrated in the case of tau protein (Mukrasch et al., 2009).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank C. Lee for helpful comments. This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A101499) and a grant from Korea Research Foundation (2010-0022224) to K.H. Han.

REFERENCES

- Arbuthnot P., Kew M. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2001;82:77–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2001.iep0082-0077-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhenda S., Cougot D., Buendia M.A., Neuveut C. Hepatitis B virus X protein molecular functions and its role in virus life cycle and pathogenesis. Adv. Cancer. Res. 2009;103:75–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)03004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui-Nguyen T.M., Pakala S.B., Sirigiri R.D., Xia W., Hung M.C., Sarin S.K., Kumar V., Slagle B.L., Kumar R. NF-kappaB signaling mediates the induction of MTA1 by hepatitis B virus transactivator protein HBx. Oncogene. 2010;29:1179–1189. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S.W., Lee S.H., Kim D.H., Ahn M.J., Kim J.S., Woo J.Y., Torizawa T., Kainosho M., Han K.H. Structural details on mdm2-p53 interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38795–38802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S.W., Kim D.H., Lee S.H., Chang I., Han K.H. Pre-structured motifs in the natively unstructured preS1 surface antigen of hepatitis B virus. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2108–2117. doi: 10.1110/ps.072983507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari F.V., Ferrari C., Mondelli M.U. Hepatitis B virus structure and biology. Microb. Pathog. 1989;6:311–325. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouard T. Structural biology: breaking the protein rules. Nature. 2011;471:151–153. doi: 10.1038/471151a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moura P.R., Rui E., de Almeida Goncalves K., Kobarg J. The cysteine residues of the hepatitis B virus oncoprotein HBx are not required for its interaction with RNA or with human p53. Virus Res. 2005;108:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztanyi Z., Csizmok V., Tompa P., Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztanyi Z., Csizmok V., Tompa P., Simon I. The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;347:827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker A.K., Obradovic Z., Romero P., Garner E.C., Brown C.J. Intrinsic protein disorder in complete genomes. Genome Inform. Ser. Workshop Genome Inform. 2000;11:161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker A.K., Silman I., Uversky V.N., Sussman J.L. Function and structure of inherently disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem D., Varmus H.E. The molecular biology of the hepatitis B viruses. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:651–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard T.D., Kneller D.G. SPARKY 3. University of California; San Francisco: 2002. ( http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Mal T.K., Jayasuryan N., Chauhan V.S. Assignment of disulphide bonds in the X protein (HBx) of hepatitis B virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;212:919–924. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildt E., Hofschneider P.H., Urban S. The role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Virol. 1996;7:333–347. [Google Scholar]

- James T.L., Liu H., Ulyanov N.B., Farr-Jones S., Zhang H., Donne D.G., Kaneko K., Groth D., Mehlhorn I., Prusiner S.B., et al. Solution structure of a 142-residue recombinant prion protein corresponding to the infectious fragment of the scrapie isoform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10086–10091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Ni Y., Lee S.H., Urban S., Han K.H. An anti-viral peptide derived from the preS1 surface protein of hepatitis B virus. BMB Rep. 2008a;41:640–644. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.9.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Kim J.C., Kim J.K., Kim H.J., Lee H.M., Choi M.S., Maeng P.J., Ahn J.K. Hepatitis B virus X protein enhances NF-kappaB activity through cooperating with VBP1. BMB Rep. 2008b;41:158–163. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Lee S.H., Chi S.W., Nam K.H., Han K.H. Backbone resonance assignment of a proteolysis-resistant fragment in the oxygen-dependent degradation domain of the hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha. Mol. Cells. 2009;27:493–496. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Mok K.H., Muhandiram R., Park K.H., Suk J.E., Kim D.H., Chang J., Sung Y.C., Choi K.Y., Han K.H. Local structural elements in the mostly unstructured transcriptional activation domain of human p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:29426–29432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.I., Kim S.O., Kwon H.J., Park J.G., Sohn M.J., Jeong S.S. Phosphorylation of purified recombinant hepatitis B virus-X protein by mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase C in vitro. J. Virol. Methods. 2001;95:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Kim D.H., Han J.J., Cha E.J., Lim J.E., Cho Y.J., Lee C., Han K.H. Understanding pre-structured motifs (PreSMos) in intrinsically unfolded proteins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2012;13:34–54. doi: 10.2174/138920312799277974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M.H., Lo S.C. Dimerization of hepatitis B viral X protein synthesized in a cell-free system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;164:14–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Zou L., Li W., Wang L., Wu Y. High-level expression and large-scale preparation of soluble HBx antigen from Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2009;54:141–147. doi: 10.1042/BA20090116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi S. Structural disorder in viral proteins. Protein Pept. Lett. 2010;17:930–931. doi: 10.2174/092986610791498975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W.S., Aldrich C., Summers J., Taylor J.M. Asymmetric replication of duck hepatitis B virus DNA in liver cells: Free minus-strand DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:3997–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukrasch M.D., Bibow S., Korukottu J., Jeganathan S., Biernat J., Griesinger C., Mandelkow E., Zweckstetter M. Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui E., de Moura P.R., Kobarg J. Expression of deletion mutants of the hepatitis B virus protein HBx in E. coli and characterization of their RNA binding activities. Virus Res. 2001;74:59–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui E., de Moura P.R., Goncalves Kde A., Kobarg J. Expression and spectroscopic analysis of a mutant hepatitis B virus onco-protein HBx without cysteine residues. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Q., Schroder C.H., Hofmann W.J., Otto G., Pichlmayr R., Bannasch P. Expression of hepatitis B virus X protein in HBV-infected human livers and hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 1998;27:1109–1120. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truant R., Antunovic J., Greenblatt J., Prives C., Cromlish J.A. Direct interaction of the hepatitis B virus HBx protein with p53 leads to inhibition by HBx of p53 response element-directed transactivation. J. Virol. 1995;69:1851–1859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1851-1859.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S., Hildt E., Eckerskorn C., Sirma H., Kekule A., Hofschneider P.H. Isolation and molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus X-protein from a baculovirus expression system. Hepatology. 1997;26:1045–1053. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V.N., Dunker A.K. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:1231–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V.N., Oldfield C.J., Dunker A.K. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waris G., Siddiqui A. Regulatory mechanisms of viral hepatitis B and C. J. Biosci. 2003;28:311–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02970150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser B., Ganem D., Seeger C., Varmus H.E. Closed circular viral DNA and asymmetrical heterogeneous forms in livers from animals infected with ground squirrel hepatitis virus. J. Virol. 1983;48:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]