Abstract

Recently, graphene oxide (GO), one of the carbon nanomaterials, has received much attention due to its unique physical and chemical properties and high potential in many research areas, including applications as a biosensor and drug delivery vehicle. Various GO-based biosensors have been developed, largely based on its surface adsorption properties for detecting biomolecules, such as nucleotides and peptides, and real-time monitoring of enzymatic reactions. In this review, we discuss recent advances in GO-based biosensors focusing on a novel assay platform for helicase activity, which was also employed in high-throughput screening to discover selective helicase inhibitors.

Keywords: biosensor, drug screening, graphene oxide, helicase, hepatitis C

INTRODUCTION

Graphene, a one-atom-thick nanomaterial with sp2 carbons arranged in a two-dimensional honeycomb structure, has received much attention recently as an emerging material with a variety of potential applications based on its unique mechanical, electrical, optical, and biological properties (Zhu et al., 2010). The oxidized form of graphene, or graphene oxide (GO, Fig. 1), has been extensively explored in both basic and biomedical research largely because of its good biocompatibility, colloidal dispersibility in aqueous solution, flexible surface chemistry, amphiphilicity, and superior fluorescence quenching capability (Loh et al., 2010; Morales-Narvaez et al., 2012). Studies have demonstrated that the GO surface may interact through pi-pi stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions (Park et al., 2013) with various biomolecules, including thrombin (Chang et al., 2010), dopamine (Wang et al., 2009), nucleic acids (Lu et al., 2009), peptides (Wang et al., 2011a), proteins (Mu et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012), and lipids (Frost et al., 2012).

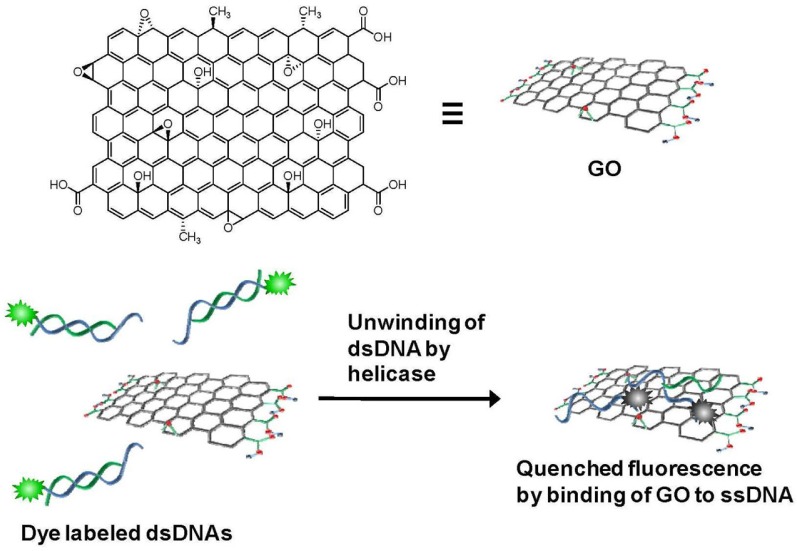

Fig. 1.

GO-based helicase activity assay. (Top) Structure of GO. (Bottom) Only unwound ssDNA, not dsDNA substrate, is adsorbed onto the GO surface to cause quenching of the fluorescent dye by energy transfer to GO.

These interactions are key to the use of GO for biological applications and enable the loading and release of various drug candidates (e.g., oligonucleotides and small molecules) and sensing probes. Additionally, the fluorescence quenching property of GO leads to a wide range of active research and development of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensors (Wang et al., 2010). The nano-sized GO (nGO, 50–300 nm) has been engineered, often by tuning GO preparation conditions, for use in intracellular delivery (Luo et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2011). The mechanism underlying GO cellular uptake remains to be determined; however, endocytosis appears to be involved in the process. Versatile covalent functionalization can be achieved through hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups present on the GO surface to enhance its physiochemical, electrochemical, or biological properties depending on the application (Huang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011).

GO-BASED HELICASE BIOSENSOR

Various GO-based enzymatic activity assay systems have been developed to target nucleases (Lee and Min, 2012), methyltransferases (Lee et al., 2011), and caspases (Wang et al., 2011b). Here, we focus on the first reported GO-based enzyme activity assay, namely the GO-based helicase activity assay (GOHA), and its use in identifying helicase nsP13 from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS CoV, SCV) (Jang et al., 2010). SARS is a viral respiratory disease in humans characterized by flu-like symptoms and high mortality rates. SCV helicases have been recognized as a primary target for direct-acting antiviral agents against SARS (Huang et al., 2008). The GOHA platform relies on the preferential binding of GO to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) over double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and the quenching of DNA-conjugated fluorescent dyes when the GO and dyes are present in close proximity. Strong adsorption of single-stranded nucleotides to GO is mediated by pi-pi stacking interactions between the aromatic rings in the exposed bases that constitute single-stranded nucleotides and the sp2 hybridized hexagonal structure of GO (Liu et al., 2008; Varghese et al., 2009). Contrary to ssDNA, dsDNA cannot interact with GO because the bases of dsDNA are located inside the double helix within the negatively charged phosphate backbone (He et al., 2010). Unwinding of dsDNA is initiated by addition of SCV helicases to a mixture of fluorescence-labeled substrate dsDNA and GO. As the helicase reaction proceeds, the fluorescence intensity decreases due to the energy transfer-mediated quenching that occurs upon binding of unwound ssDNA to the GO surface (Fig. 1). The GOHA platform is a good example of a GO-based enzymatic biosensor due to its highly selective adsorption to ssDNA and exceptionally high fluorescence quenching ability. Further application of GOHA for more pathophysiological relevance has been extensively studied including a robust and cost-effective drug discovery platform.

HEPATITIS C VIRUS NS3 HELICASE AND mGOHA FOR DRUG DISCOVERY

Hepatitis C is an infectious liver disease that affects more than 170 million people worldwide. Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) leads to severe liver disease, including cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma (Choo et al., 1989; Francesco et al., 2005). At present, a combination of PEG-conjugated interferon-α and ribavirin is routinely prescribed for treating hepatitis C infection. Interferon-α is an immune booster and ribavirin is a nucleoside-mimicking derivative that causes lethal mutations in the virus during RNA replication and indirectly contributes to sustaining the immune response against HCV genotypes 1, 2, and 3. However, this pharmacological intervention has showed only limited efficacy with significant side effects, including hemolytic anemia, depression, and fatigue. Frequent genetic mutations in HCV and drug resistance also significantly limit the effectiveness of current hepatitis treatments. For higher therapeutic efficacy, new drugs have been anticipated to target more genetically conserved proteins of HCV such as proteases. Direct-acting antiviral agents targeting the non-structural protein 3-4A serine protease (NS3-4A) (Lee et al., 2012) and non-structural protein 5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5B RdRp) (Farnik and Zeuzem, 2012) in the viral replication cycle have been reported to be more effective than conventional therapy. Two inhibitors of the NS3-4A protease, telaprevir (Vertex) and boceprevir (Merck), were recently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating HCV infection.

The HCV NS3 protein contains a C-terminal RNA helicase domain that hydrolyzes ATP to catalyze the unwinding of dsDNA or dsRNA into single-stranded forms. The N-terminal serine protease domain cleaves the HCV polyprotein and, consequently, releases mature proteins. The HCV NS3 helicase is one of the essential enzymes of HCV along with NS3-4A serine protease and NS5B RdRp, which are required for processing HCV proteins and viral replication. The HCV NS3 helicase has long been considered another important target for the development of hepatitis C therapeutics (Borowski et al., 2002; Frick, 2007); however, identification of potent inhibitors using chemical library screening has been challenging because the available helicase assay systems are incompatible with high-throughput formats.

Numerous technologies have been developed to measure helicase activity in vitro, including fluorescence and radiolabeled gel electrophoresis (Kwong and Risano, 1998), scintillation proximity assay (SPA) (Kyono et al., 1998), FlashPlate (Hicham Alaoui-Ismaili et al., 2000), electrochemiluminescence (ECL) (Zhang et al., 2001), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Hsu et al., 1998), FRET (Porter et al., 1998), time-resolving resonance energy transfer (TR-RET) (Earnshaw et al., 1999), and molecular beacon helicase assay (MBHA) (Belon and Frick, 2008) (Table 1). Some assay methods have contributed significantly to unveiling the helicase reaction mechanism at the molecular level. However, according to the NIH screen data (Mukherjee et al., 2012), some antiviral candidates identified by currently available helicase assays exhibited poor activity in cell-based analysis and even turned out to interfere with the assay itself and produced false positives.

Table 1.

Currently available HCV NS3 helicase activity assay platforms

| Assay | Detection | References |

|---|---|---|

| PAGE | Gel electrophoresis and radioimaging | Tai et al. (1996) |

| SPA | SPA beads, microplate scintillation counter | Kyono et al. (1998) |

| FlashPlate | FlashPlates, microplate scintillation counter | Hichem Alaoui-Ismaili et al. (2000) |

| ECL | Magnetic flow cell, ECL instrument | Zhang et al. (2001) |

| ELISA | UV-vis spectrophotometer (A450) | Hsu et al. (1998) |

| FRET | Fluorescence spectrophotometer | Porter et al. (1998) |

| TR-RET | Fluorescence spectrophotometer | Earnshaw et al. (1999) |

| SSB | Gel electrophoresis and fluorescence spectrophotometer | Rajagopal et al. (2008) |

| 3-AP | Fluorescence spectrophotometer | Raney et al. (1994) |

| MBHA | Fluorescence spectrophotometer | Belon and Frick (2008) |

See text for explanation on abbreviations

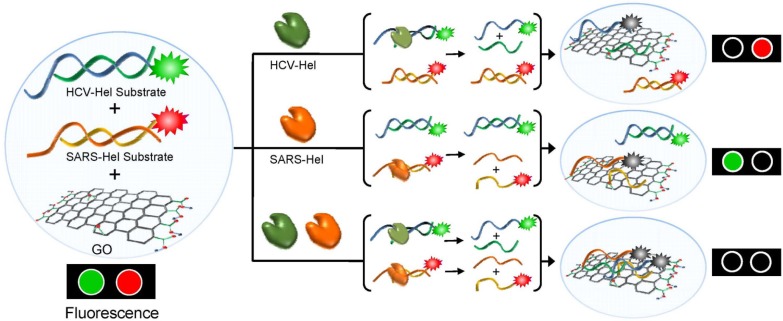

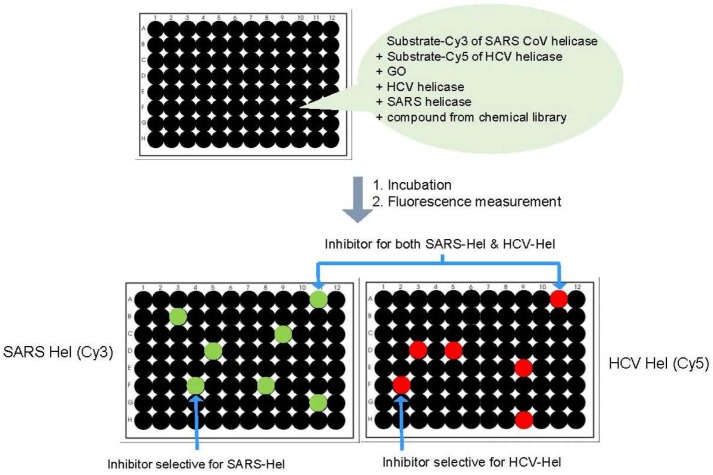

Recently, our laboratory reported a multiplexed helicase assay platform based on GO (called mGOHA) that exhibits robust sensibility and high-throughput compatibility (Jang et al., 2013) (Fig. 2). Briefly, mGOHA employs SCV helicase and HCV NS3 helicase in a single mixed solution with DNA substrates labeled with two distinct fluorescent dyes, Cy3 and Cy5, respectively. The substrates were designed to selectively recognize each helicase to ensure orthogonal reactivity. Approximately 10,000 small molecules underwent a high-throughput screen using the mGOHA platform to identify potent inhibitors of target helicases (Fig. 3). After the primary and secondary screens, five inhibitors specific to each helicase and five inhibitors active towards both helicases were identified. The inhibitors exhibited 50–500 μM of IC50 values on target helicases. Furthermore, most directly inhibited the ATPase activity of the target helicase. Among the five compounds identified as HCV NS3 helicase inhibitors, two compounds showed a considerable inhibitory effect on HCV gene replication following infection of the human liver cell line Huh-7. Collectively, mGOHA was demonstrated to be a successful high-throughput screening method that yields highly potent antiviral candidates without interfering with the assay itself and producing false positives. This novel assay also overcame the limitations of existing assay methods by providing reliable, reproducible, real-time quantitative monitoring of helicase activity.

Fig. 2.

mGOHA. Two different helicases, SCV helicase and HCV NS3 helicase, selectively recognize cognate dsDNA substrates labeled with two distinct fluorescent dyes. In a mixed solution, activities of the individual helicases are quantitatively measured with real-time monitoring.

Fig. 3.

Procedure for small-molecule screening against two helicases, SCV helicase and HCV NS3 helicase, based on mGOHA.

CONCLUSION

A helicase assay based on GO, called GOHA, was developed and successfully implemented in multiplexed high-throughput chemical screening to identify potent helicase inhibitors, which are potentially of clinical interest to treat hepatitis C and SARS. The new assay enables quantitative, reliable, and real-time monitoring of helicase activity by simply tracking changes in fluorescence intensity. The ability to perform multiplexed screening is also advantageous because it reduces costs and labor while providing near instantaneous information on the relative selectivity of the identified inhibitors.

To effectively treat HCV infection, direct-acting antiviral agents should be developed to complement the standard interferon-α and ribavirin treatments. In this regard, discovery of new inhibitors of HCV NS3 helicase will be a great addition to existing options for direct-acting antiviral agents. The GOHA will be further harnessed to identify other helicase inhibitors to treat additional viral infections in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the Basic Science Research Program, National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF; 2011-0017356 to D.-H.M., 2012-0003217 to M.J.L.) through the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) of the Korean government.

REFERENCES

- Belon A, Frick DN. Monitoring helicase activity with molecular beacons. BioTechniques. 2008;45:433–440. doi: 10.2144/000112834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski P, Niebuhr A, Schmitz H, Hosmane RS, Bretner M, Siwecka MA, Kulikowski T. NTPase/helicase of Flaviviridae: inhibitors and inhibition of the enzyme. Acta Biochim Pol. 2002;49:597–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HX, Tang LH, Wang Y, Jiang J, Li J. Graphene fluorescence resonance energy transfer aptasensor for thrombin detection. Anal Chem. 2010;82:2341–2346. doi: 10.1021/ac9025384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw DL, Moore KJ, Greenwood CJ, Djaballah H, Jurewics AJ, Murray J, Pope AJ. Time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer DNA helicase assays for high throughput screening. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:239–248. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnik H, Zeuzem S. New antiviral therapies in the management of HCV infection. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:771–783. doi: 10.3851/IMP2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesco RD, Migliaccio G. Challenges and successes in developing new therapies for hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:953–960. doi: 10.1038/nature04080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick DN. The hepatitis C virus NS3 protein: a model RNA helicase and potential drug target. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2007;9:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R, Jönsson GE, Chakarov D, Svedhem S, Kasemo B. Graphene oxide and lipid membranes: interactions and nanocomposite structures. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3356–3362. doi: 10.1021/nl203107k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Song B, Li D, Zhu C, Qi W, Wen Y, Wang L, Song S, Fang H, Fan C. A graphene nanoprobe for rapid, sensitive, and multicolor fluorescent DNA analysis. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Hicham Alaoui-Ismaili M, Gervais C, Brunette S, Gouin G, Hamel M, Rando F, Bedard J. A novel high throughput screening assay for HCV NS3 helicase activity. Antiviral Res. 2000;46:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(00)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CC, Hwang LH, Huang YW, Chi WK, Chu D, Chen DS. An ELISA for RNA helicase activity: application as an assay of the NS3 helicase of hepatitis C virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:594–599. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JD, Zheng BJ, Sun HZ. Helicases as antiviral drug targets. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:S36–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yin Z, Wu S, Qu X, He Q, Zhang Q, Yan Q, Boey F, Zhang G. Graphene-based materials: synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Small. 2011;7:1876–1902. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Kim YK, Kwon HM, Yeo WS, Kim DE, Min DH. A graphene-based platform for the assay of duplex-DNA unwinding by helicase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:5703–5707. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Ryoo SR, Kim YK, Yoon S, Kim H, Han SW, Choi BS, Kim DE, Min DH. Discovery of hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase inhibitors by a multiplexed, high-throughput helicase activity assay based on graphene oxde. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:2340–2344. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong AD, Risano C. Development of a hepatitis C virus RNA helicase high throughput assay. In: Kinchington D, Schinazi RF, editors. In Antiviral Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyono K, Miyashiro M, Taguchi I. Detection of hepatitis C virus helicase activity using the scintillation proximity assay system. Anal Biochem. 1998;257:120–126. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Min DH. A simple fluorometric assay for DNA exonuclease activity based on graphene oxide. Analyst. 2012;137:2024–2026. doi: 10.1039/c2an16214h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim YK, Min DH. A new assay for endonuclease/methyltransferase activities based on graphene oxide. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8906–8912. doi: 10.1021/ac201298r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Tong CY, Wong T, Wilkinson M. New therapies for chronic hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of evidence from clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:342–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Frankowski KJ, Belon CA, Neuenswander B, Ndjomou J, Hanson AM, Shanahan MA, Schoenen FJ, Blagg BSJ, Aube J, et al. Optimization of potent hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase inhibitors isolated from the yellow dyes thioflavins S and primuline. J Med Chem. 2012;55:3319–3330. doi: 10.1021/jm300021v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Robinson JT, Sun X, Dai H. PEGylated nanographene oxide for delivery of water-insoluble cancer drugs. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10876–10877. doi: 10.1021/ja803688x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh KP, Bao Q, Eda G, Chhowalla M. Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications. Nat Chem. 2010;2:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nchem.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN. A graphene platform for sensing biomolecules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4785–4787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Cote LJ, Tung VC, Tan AT, Goins PE, Wu J, Huang J. Graphene oxide nanocolloids. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17667–17669. doi: 10.1021/ja1078943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Narváez E, Pérez-López B, Pires LB, Merkoçi A. Simple Förster resonance energy transfer evidence for the ultrahigh quantum dot quenching efficiency by graphene oxide compared to other carbon structures. Carbon. 2012;2:2987–2993. [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q, Su G, Li L, Gilbertson BO, Yu LH, Zhang Q, Sun YP, Yan B. Size-dependent cell uptake of protein-coated graphene oxide nanosheets. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4:2259–2266. doi: 10.1021/am300253c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Hanson AM, Shadrick WR, Ndjomou J, Sweeney NL, Hernandez JJ, Bartczak D, Li K, Frankowski KJ, Heck JA, et al. Identification and analysis of hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase inhibitors using nucleic acid binding assays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8607–8621. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S, Aksay IA. Factors controlling the size of graphene oxide sheets produced via the graphite oxide route. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4073–4083. doi: 10.1021/nn200666r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Na HK, Min DH, Kim DE. Desorption of single-stranded nucleic acids from graphene oxide by disruption of hydrogen bonding. Analyst. 2013;138:1745–1749. doi: 10.1039/c3an36493c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DJ, Short SA, Hanlon MH, Preugscaht F, Wilson JE, Willard J, Consler TG. Product release is the major contributor to kcat for the hepatitis C virus helicase-catalyzed strand separation of short duplex DNA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18906–18914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal V, Patel SS. Single strand binding proteins increase the processivity of DNA unwinding by the hepatitis C virus helicase. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raney KD, Sowers LC, Millar DP, Benkovic SJ. A fluorescence-based assay for monitoring helicase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6644–6648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai CL, Chi WK, Chen DS, Hwang LH. The helicase activity associated with hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) J Virol. 1996;70:8477–8484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8477-8484.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese N, Mogera U, Govindaraj A, Das A, Maiti PK, Sood AK, Rao CNR. Binding of DNA nucleobases and nucleosides with graphene. Chemphyschem. 2009;10:206–210. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li YM, Tang LH, Lu J, Li J. Application of graphene modified electrode for selective detection of dopamine. Electrochem Commun. 2009;11:889–892. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Arnold JJ, Uchida A, Raney D, Cameron CE. Phosphate release contributes to the rate-limiting step for unwinding by an RNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1312–1324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li Z, Wang J, Li J, Lin Y. Graphene and graphene oxide: biofunctionalization and applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2011a;29:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang Q, Chu X, Chen T, Ge J, Yu R. Graphene oxide-peptide conjugate as an intracellular protease sensor for caspase-3 activation imaging in live cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011b;50:7065–7069. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Schwartz G, O’Donnell M, Harrison RK. Development of a novel helicase assay using electrochemiluminescence. Anal Biochem. 2001;293:31–37. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Guo ZY, Huang DQ, Liu Z, Guo X, Zhong H. Synergistic effect of chemo-photothermal therapy using PEGylated graphene oxide. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8555–8561. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J, Huang X, Zhou X, Wu H, Guo S. Assembly of graphene oxide-enzyme conjugates through hydrophobic interaction. Small. 2012;8:154–159. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Murali S, Cai W, Li X, Suk JW, Potts JR, Ruoff RS. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv Mater. 2010;22:3906–3924. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]