Abstract

Sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, remains a potentially lethal condition. (S)-1-α-Naphthylmethyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (CKD712) is noted as a drug candidate for sepsis. Many studies have demonstrated its significant anti-inflammatory effects. Here we first examined whether CKD712 inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced arachidonic acid (AA) release in the RAW 264.7 mouse monocyte cell line, and subsequently, its inhibitory mechanisms. CKD712 reversed LPS-associated morphological changes in the RAW 264.7 cells, and inhibited LPS-induced release of AA in a concentration-dependent manner. The inhibition was apparently due to the diminished expression of a cytosolic form of phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) by CKD712, resulting from reduced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, CKD712 inhibited the activation of ERK1/2 and SAP/JNK, but not of p38 MAPK. CKD712 had no effect on the activity or phosphorylation of cPLA2 and on calcium influx. Our results collectively suggest that CKD712 inhibits LPS-induced AA release through the inhibition of a MAPKs/NF-κB pathway leading to reduced cPLA2 expression in RAW 264.7 cells.

Keywords: CKD712, cPLA2, MAPKs, NF-κB, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis (Septicemia, blood poisoning) represents a whole-body inflammatory state that is usually caused by infection with gram-negative bacteria (Levy et al., 2003). Endotoxins from gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli that are released into the blood stream cause decreased tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery, multiple organ failure (septic shock), and death (Kumar Vinay, 2007). Sepsis is also known as a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), and remains a major challenge in medicine (Baron et al., 2006).

CKD712, (S)-1-α-naphthylmethyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline, is a newly synthesized tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid and an (S) enantiomer. It was originally extracted from Aconitum (known as Monkshood), and initially used as a cardio tonic, and has long been considered as a very important drug. It has also been used as a heart stimulant and diuretic in oriental herbal medicine (Zhou and Du, 2003). Kang et al. (1999) reported that the (S)-form, which has shown more potent anti-inflammatory effects than the (R)-form or racemic mixture, significantly inhibited inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, with concomitant decrease in nitric oxide (NO) production, by blocking the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), leading to increased survival rates in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated murine model of sepsis (Park et al., 2006; 2011).

A cytosolic form of phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) hydrolyzes phospholipids to arachidonic acid (AA) and lysophospholipids; this is the rate-limiting step during pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production (Clark et al., 1995; Leslie, 1997). There are several pathways for AA production through the activation and translocation to cell membrane of cPLA2; by increases in a) intracellular Ca2+ levels (Glover et al., 1995), b) direct activation by ceramide-1-phosphate (Lamour et al., 2009), c) phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Lin et al., 1993), and d) transcriptional expression (Clark et al., 1995). Recent evidence shows that cPLA2 could be an essential effector in the pathogenesis of the septic shock (Kim et al., 2006; Levy et al., 2000; Roshak et al., 1994) and acute lung injury caused by the sepsis syndrome (Nagase et al., 2000; 2003). Moreover, cPLA2, and not the secretory form of PLA2 (sPLA2), plays an important role in LPS-induced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) formation in human monocytes (Roshak et al., 1994). The disruption of a gene encoding cPLA2, and subsequent treatment with a potent inhibitor of cPLA2, such as arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, significantly attenuated LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice (Kim et al., 2006; Nagase et al., 2000; 2003). These studies suggest that the pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2 could be a novel therapeutic approach to sepsis.

In the present study, we have demonstrated the inhibitory effect of CKD712 on LPS-induced AA release and PGE2 production. These effects may be due to inhibition of cPLA2 expression, through the activation of a MAPK/NF-κB pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

LPS (from E. coli, serotype O128:B12), protease inhibitor cocktail, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltrazolium bromide], and dithiothreitol (DTT) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (USA). Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3), SP600125, PD98059, and SB203580 were obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, USA). Anti-cPLA2, anti-COX-2, and anti-GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). Anti-MAPK antibodies (p42/44, p38 MAPK, and JNK) and anti-phospho-MAPK (p-p42/44, p-p38 MAPK, and p-JNK) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling technology® (USA). 1-Stearoyl-2-(1-14C) arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho- choline [2-(1-14C) AA-GPC] (55 μCi/mol) and (5,6,8,9,11,12,14, 15-3H) arachidonic acid [(3H) AA] were purchased from Amersham Life Science Co. LTD. (UK). The plastic ware for cell culture was purchased from Nunc Co. (Denmark). All other chemicals were of highest purity available from commercial sources. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) enzyme immunoassay kit was from Sapphire Bioscience (Australia). The Nuclear Extraction kit and EMSA Gel Shift kit were purchased from Panomics (USA). Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kits was purchased from Invitrogen (Molecular Probes™, USA). (S)-Tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid (CKD712) was obtained from the Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Co. (Korea).

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells were obtained from ATCC (USA). The growth medium consisted of DMEM (USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1× antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin; Gibco). The cultures were maintained in an incubator at 37°C, in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Assay for arachidonic acid release

Sub-confluent cells in 6-well plates were labeled for 24 h with [3H] arachidonic acid (0.5 μCi/ml) in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. After labeling, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed 3 times with serum-free DMEM, followed by 30 min of incubation in this medium. After incubation, the indicated concentrations of CKD712 were added, and the cells were incubated for 1 h. Next, 1 μg/ml LPS was added, and arachidonic acid release was measured at the indicated times. To measure stimulated arachidonic acid release, an aliquot of medium was removed and centrifuged. The radioactivity in 100 μl of the supernatant was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 2910TR/Perkin Elmer LAS). The radioactivity of released arachidonic acid was normalized to the total radioactivity of the monolayer extracted with 1% Triton X-100.

Preparation of RAW 264.7-derived cPLA2

RAW 264.7 cells were grown in 150 × 20-mm petri dishes and washed twice with TBS. The cells were harvested in homogenizing buffer containing 0.12 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 75 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. The cell suspension was sonicated on ice 6 times for 3 s, with 5 s-intervals between each pulse to maintain ice-cold condition. The sonicated cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (lysates) was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatants (cytosolic fraction) were used as a source of cytosolic PLA2. For direct binding studies, cPLA2 was partially purified from the cytosolic fraction of RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were grown in T175 flasks, and the cytosolic fractions were prepared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g after sonication in 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0 (buffer H). The prepared sample was applied to a HiTrap™ Heparin HP column (1 ml, GE Healthcare) that was pre-equilibrated with buffer H at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Because enzyme activity was recovered in the unbound fraction, unbound path-through (PT) protein was eluted with 5 ml of buffer H and diluted with equal volumes of 1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 (buffer A). The diluted PT fraction was applied to MonoQ™ column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Unbound protein was eluted and rinsed with 25 ml of buffer A. The portion containing active enzyme was eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min using a 20-ml linear gradient of buffer A containing 1 M NaCl. An aliquot (20 μl) of each fraction (1 ml) was assayed for cPLA2 activity. The fraction exhibiting the highest activity was used for testing the direct effects of CKD712 on cPLA2.

Assay of PLA2 activity

PLA2 activity was assayed using the supernatant and pellet after centrifugation at 100,000 × g. Briefly, the standard incubation system (100 μl) for assaying PLA2 activity contained PLA2 preparations, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2 and 4.5 nmol of substrate 2-[1-14C] AA-GPC (approximately 55,000 cpm). The reactions were carried out at 37°C for 1 h and stopped by adding 560 μl of modified Dole’s reagent (n-heptane/isopropyl alcohol/1 N-H2SO4; 400/390/10, v/v) (Kim and Bonventre, 1993), and 110 μl of water. Then, the released [14C] AA was extracted and quantified.

Immunoblotting

RAW 264.7 cells were plated in 150 × 20-mm petri dishes at a density of ∼2 × 106 cells per plate. After 24 h, the media were replaced with serum-free DMEM for 30 min, and the cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of CKD712 for 1 h, and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 8 h. Treated cells were washed twice with TBS and collected in homogenizing buffer (75 mM Tris-HCl, 12 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0, 20 μM pepstatin, 10 mM mercaptoethanol, 20 μM leupeptin, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cells were homogenized in a sonicator and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min to remove debris. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h, and the pellet was resuspended in homogenizing buffer. The protein concentrations of the supernatants and pellets were measured using Bradford’s reagent (Biorad). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using an 8% gel, and then electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, USA) in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) containing 190 mM glycine, 4 mM SDS, and 20% methanol. These nitro-cellulose membranes were incubated with a blocking buffer containing 5% non-fat dry skim milk for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with mouse anti-cPLA2 primary antibody (1:2,000 dilution) overnight at 4°C with constant shaking. Unbound antibody was removed with TBST, antibody-binding sites were detected by using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (incubation for 2 h at 4°C), and blots were developed using a chromogenic substrate (Immuno Pure NBT/BCIP Substrate kit, Pierce Co., USA).

PGE2 enzyme immunoassay

The concentration of PGE2 in the medium used to culture RAW264.7 cells was measured using an ELISA kit (Sapphire Bioscience). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with CKD712 at various concentrations. After 1 h, LPS at 1 μg/ml was added, and the cells were incubated for 8 h. The cell culture medium was then sampled for PGE2 detection using anti-PGE2 immunoglobulin.

Calcium influx assay

The effect of CKD712 on calcium influx in RAW 264.7 cells was detected using Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kits (Invitrogen, USA). RAW 264.7 cells were plated in a 96-well black plate at 5 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h, the medium was removed from the well. Then, the procedure was continued according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Calcium influx was detected by fluorescence using the settings appropriate for excitation at 494 nm and emission at 516 nm. Analysis was operated with Synergy™ 2 Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek®, USA).

EMSA gel shift assay

RAW 264.7 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of ∼2 × 105 cells per well. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM for 30 min, the cells were incubated with the indicated CKD712 concentrations for 1 h, and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 4 h. After stimulation, the cell nuclei were extracted using a Nuclear Extraction kit (USA). Cells were washed twice in PBS and lysed on ice with gentle shaking for 10 min in extraction buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktail – Sigma –, and 4% IGEPAL). Cells were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was mixed with buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9; 400 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 10% glycerol; protease inhibitor; 10 mM DTT), and vigorously vortexed for 10 s. The mixture was then incubated at 4°C for 2 h with gentle shaking. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 × g, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Nuclear extracts (5 μg) were incubated with 1× binding buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ammonium sulfate, 1 mM DTT, 30 mM KCl, and 0.2% Tween-20) and 1 μg of poly d (I-C) in nuclease-free water for 5 min at room temperature. Biotin-labeled probe was then added; NF-κB: (5′ → 3′) AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C. The reaction mixture was incubated at 15°C for 30 min. The samples were electrophoresed on a 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5% TBE for 50 min at 120 V, and then transferred in 0.5% TBE onto a nylon membrane at 300 mA for 30 min. After transfer, the sample on the membrane was fixed by UV cross-linking at 120 mJ for 3 min. This membrane was then blocked with 1% blocking reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at room temperature for 15 min. The biotin-labeled probe was detected with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1:20,000 dilution, Pierce), for 15 min at room temperature. After washing 3 times, the membrane was overlaid with lumino/en-hancer and substrate for 5 min at room temperature. The image was acquired using ChemiDoc™ XRS (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (S.D.) of the indicated number of experiments. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CKD712 inhibits LPS-induced morphological changes in RAW264.7 cells

LPS is known to induce a morphological change in RAW 264.7 cells (Saxena et al., 2003). Thus, we confirmed the change induced by LPS, and examined the effects of CKD712 on this change using optical microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2, 1 μg/ml LPS significantly induced the morphological change at 2 h, which was subsequently inhibited by CKD712 in a concentration-dependent manner.

Fig. 2.

Effect of CKD712 on LPS-induced morphological changes in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 1 h in serum-free DMEM, and then incubated with the indicated concentrations of CKD712. After 30 min, the cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 2 h. Black arrows represent morphologically altered RAW 264.7 cells. The morphology of RAW 264.7 cells was visualized using optical microscopy (200× magnification).

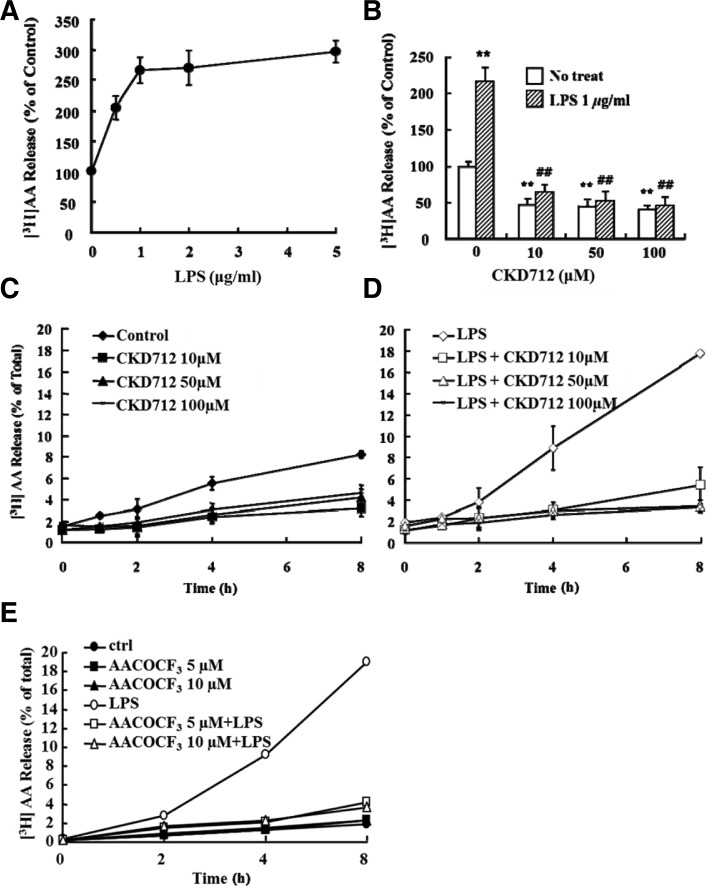

LPS induced AA release, which is inhibited by AACOCF3, and CKD712 inhibited this AA release

When RAW 264.7 cells pre-incubated with [3H]AA were treated with LPS for 8 h, we observed a concentration-dependent increase in AA release with saturation at 1 μg/ml (Fig. 3A); this release was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by CKD712 (Fig. 3B). The inhibitory effect of CKD712 on AA release was observed not only in an LPS-free culture system (Fig. 3C), but also in an LPS-treated system (Fig. 3D). The inhibitory effect of CKD712 was maximal at 100 μM, with almost complete inhibition of AA release. On the other hand, AACOCF3, a specific cPLA2 inhibitor, (Riendeau et al., 1994), was used to identify the forms of PLA2 that are involved in LPS-induced AA release; AACOCF3 was added to both LPS-free and LPS-treated systems. As shown in Fig. 3E, AACOCF3 inhibited AA release in both systems.

Fig. 3.

Effect of CKD712 on LPS-induced [3H] AA release in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS with 0.5 μCi/ml [3H] AA, washed 3 times with free DMEM, and then incubated for 8 h with various concentrations of LPS. The supernatants were then collected and tested for radioactivity (Tri-Carb 2910TR/ Perkin Elmer LAS). The radioactivity released by untreated cells was considered 100%. (B) [3H] AA release induced by LPS in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 24 h in complete DMEM with 0.5 μCi/ml [3H] AA, washed 3 times with free DMEM, and then incubated with the indicated concentrations of CKD712. After 1 h, incubated cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 8 h. The supernatants were then collected and the radioactivity was counted (Tri-Carb 2910TR/ Perkin Elmer LAS). The radioactivity released by untreated cells was considered 100%. After treatment with only CKD712 (C) or CKD712 and LPS (D), the [3H] AA released was detected in the supernatant over an 8-h time course (0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h). (E) After treatment of AACOCF3 (0, 5, and 10 μM) with or without LPS treatment, released [3H] AA was detected in the supernatant over an 8-h time course (0, 2, 4, and 8 h). **p < 0.01 compared with no treated-control group, ##p < 0.01 compared with LPS and 0 μM-treated group.

Investigation of the mechanism by which CKD712 inhibits LPS-induced [3H] AA release

We examined the direct effects of CKD712 on cPLA2 activity in a cell-free system. First, to separate cPLA2 from other forms of PLA2 such as sPLA2, or a Ca2+-independent form, cPLA2 was partially purified according to the activity profile from RAW 264.7 cell homogenates by using a Heparin HP hydrophobic column (Fig. 4A) and MonoQ™ anion exchange column (Fig. 4B). To confirm whether the active fractions displayed mostly cPLA2 activity, fractions were pre-incubated with AACOCF3 and DTT, a sPLA2 inhibitor. The PLA2 activity in the heparin-non-binding fractions was inhibited by AACOCF3 in a concentration-dependent manner, but not DTT (Fig. 4C), whereas the activity in the heparin-binding fractions was inhibited by DTT, but not AACOCF3 (Data not shown). The activity of the heparin-non-binding fractions was further purified using a MonoQ™ anion exchange column, and the active fractions incubated with various concentrations of CKD712. CKD712 showed no significant effect on this cPLA2 activity (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

CKD712 has no direct effect on purified cPLA2 from RAW 264.7 cells. cPLA2 was partially purified from RAW 264.7 cells following the procedure outlined in the “Materials and Methods”. (A) The prepared sample was applied to HiTrap TM Heparin HP column (1 ml, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer H at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. (B) The PT of Hi-Trap™ Heparin HP column, enzyme activity was recovered in unbound path-through (PT), was applied to Mono Q TM column (GE healthcare). (C) Purified cPLA2 was incubated with AACOCF3 (cPLA2 inhibitor) or DTT (sPLA2 inhibitor) or CKD712 at various concentration for 10 min, and then, PLA2 activity was assayed with the standard assay system.

Next, we examined in an indirect manner, the regulatory mechanism by which CKD712 inhibits cPLA2. The activity of cPLA2 enzyme could be stably increased by its phosphorylation, Ca2+ binding to its C2 domain (Leslie, 1997), or upregulation of enzyme expression. We examined the effect of CKD712 on the expression levels of cPLA2 and its activating mechanism. As shown in Fig. 5A, the protein level of cPLA2 in cell homogenates increased by 1 μg/ml LPS and was attenuated by CKD712 in a concentration-dependent manner. On the other hand, the inhibitory effect of CKD712 on cPLA2 expression was paralleled with that of its activity. CKD712 decreased cPLA2 activity in both the control and LPS-treated cells (Fig. 5A). To examine whether CKD712 inhibits cPLA2 phosphorylation, the cells were pre-treated with CKD712 at various concentrations, and stimulated with LPS for 0.5 h. As shown in Fig. 5B, whereas CKD712 decreased LPS-induced expression of cPLA2, the level of phosphorylation of cPLA2 was not affected even at 100 μM CKD712.

Fig. 5.

CKD712 downregulates the activity and expression level but not phosphorylation of cPLA2. (A) RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 1 h with the indicated concentrations of CKD712. After 1 h, the cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 8 h. Cells were then harvested and washed 2 times with TBS, and sonicated in lysis buffer (120 mM NaCl, 7 mM Tris-Cl, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0). The sonicated cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants (lysates) were assayed for cPLA2 activity, and immunobloted with anti-cPLA2 antibody. (B) RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with LPS for 30 min after pre-incubation with CKD712 at 0, 1, 10, 50, and 100 μM for 30 min. The lysate was then immunobloted with anti-cPLA2 and anti-phospho-cPLA2 antibodies. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with no treated-control group, ##p < 0.01 compared with LPS and 0 μM-treated group.

Next, to examine whether CKD712 regulates cPLA2 activity through the influx of Ca2+, the cells was pre-treated with CKD712 at various concentrations and assayed for Ca2+ influx by detecting the intensity at 516 nm using Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kits. A23187 immediately evoked Ca2+ influx, which gradually decreased (Fig. 6B), whereas LPS did not induce Ca2+ influx (Fig. 6A). In addition, pre-treatment with CKD712 even up to a high dose (100 μM) failed to decrease Ca2+ influx (Fig. 6B). These results collectively suggest that CKD712 may inhibit cPLA2 activation by inhibiting the expression of cPLA2, and not via its phosphorylation or increased Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 6.

Effect of CKD712 on cPLA2 activation by calcium influx. RAW 264.7 cells were plated in 96-well black plates at 5 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h, calcium influx was detected with Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kits (Invitrogen, USA) at 516 nm wavelength. Calcium influx into the cytosol was detected in cells treated with LPS (A) and A23187 (B) for 10 s (arrows).

Effect of CKD712 on LPS-induced NF-κB activation

To investigate how CKD712 inhibits the expression of cPLA2, we focused on the activation of the NF-κB transcription factor and MAPK pathway that the effects of LPS are known to be highly dependent upon (Dieter et al., 2002; Gilroy et al., 2004). First, to elucidate whether CKD712 blocked NF-κB activation by LPS, the cells were pretreated with CKD712 at various concentrations, and then stimulated by LPS. After 4 h, the interaction of nuclear proteins with a 65-kDa NF-κB probe was detected using an EMSA gel shift assay. Figure 7A shows that CKD712 significantly blocked LPS-induced activation and nuclear translocation of NK-κB. On the other hand, our data show that CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced expression of cPLA2 and COX-2 (Fig. 7B). Accordingly, Fig. 7C shows that LPS significantly increased PGE2 levels, and CKD712 blocked PGE2 release from RAW264.7 cells.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of LPS induced NF-κB activation by CKD712. After CKD712 was treated at indicated concentrations for 1 h in free DMEM, RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 4 h. Lysates and nuclear extracts of cells were prepared using a Nuclear Extraction kit (Panomics, USA). (A) Five micrograms of nuclear extract was incubated with a biotin-labeled probe; NF-κB: (5′ → 3′) AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C, at 15°C for 30 min. Images of probes bound with nuclear extract were acquired using ChemiDoc™ XRS (Bio-Rad), and the lysates were immunobloted with anti-cPLA2 and anti-COX-2 antibodies (B) After incubation with CKD712 and LPS for 8 h, released PGE2 was detected, in the medium used to grow the cells, by using anti-PGE2 antibody (PGE2 ELISA kit; Sapphire Bioscience). **p < 0.01 compared with no treated-control group, ##p < 0.01 compared with LPS and 0 μM-treated group.

Effect of CKD712 on LPS-induced MAPK activation

LPS-induced NF-κB activation is known to be associated with the activation of the MAPK pathway (Luo et al., 2006). Therefore, to examine whether LPS mediates the activation of MAPK pathway, the effects of LPS on the phosphorylation of MAPKs was detected using Western blot analysis, after the cells were treated with PD98059, SP600125, and SB203580, the inhibitors for ERK1/2, SAP/JNK, and p38 MAPK, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8A, LPS markedly phosphorylated MAPKs. Our data show that SAP/JNK and p38 MAPK phosphorylation was blocked by the respective inhibitors; however, PD98059 did not inhibit LPS-induced activation of ERK1/2 under the conditions used in this experiment (Fig. 8A). We then examined the effects of CKD712 on the activation of MAPKs. Figure 8B shows that CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and SAP/JNK in a concentration-dependent manner, but failed to inhibit LPS-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK.

Fig. 8.

Inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK/SAP by CKD712. After the cells were treated with MAPK inhibitors at 5 μM (A) or CKD712 at 0, 1, 10, 50, and 100 μM (B) for 0.5 h in free DMEM, RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 0.5 h. Next, the cells were harvested and washed 2 times in TBS, and then sonicated in lysis buffer (120 mM NaCl, 75 mM Tris-Cl, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0). The sonicated cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants (lysates) were immunobloted with anti-MAPK, anti-phospho-MAPK, anti-cPLA2, and anti-phospho-cPLA2 antibodies. GAPDH was used as a protein-loading control; its phospho-protein form (A) was detected by anti-GAPDH, not by anti-phospho-GAPDH. For immunob-lotting of phospho-proteins, BSA was used instead of skim milk, and NaN3 was excluded from all process-sing.

To examine the effects of CKD712 and MAPK inhibitors on cPLA2and AA release, the activity and expression of cPLA2 was analyzed. Although MAPK inhibitors decreased LPS-induced release of AA, CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced release of AA to lower than the control level as a stronger inhibitor compared to any of the MAPK inhibitors (Fig. 9A). Concomitantly, LPS increased the expression and activity of cPLA2 by 1.4 folds and ∼1.8 folds, respectively (Figs. 9B and 9C). CKD712, PD98059, and SP600125 blocked both the expression and activity of cPLA2 up to the activity of the control or lower, whereas SB203580 showed mild inhibition of the LPS-induced effects (Fig. 9C). Our results show that CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced expression of cPLA2, which is mediated by NF-κB activation through ERK1/2 and/or SAP/JNK pathway rather than p38 MAPK.

Fig. 9.

LPS-induced AA release and cPLA2 expression is related to the MAPK-activating pathway. (A) [3H] AA release was induced by LPS in RAW 264.7 cells, which were incubated for 24 h in complete DMEM with 0.5 μCi/ml [3H] AA, washed 3 times with free DMEM, and then incubated with MAPK inhibitors or CKD712. MAPK inhibitors were added at IC50 concentrations that downregulate cytokine levels in monocytes: SP600125 (JNK/SAP inhibitor), IC50: 5–10 μM, SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), IC50: 50–100 nM, and PD98059 (ERK1/2 inhibitor), IC50: 2 μM. After 0.5 h, the incubated cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 8 h. [3H] AA was detected in the supernatant over an 8-h time course (0, 2, 4, 40, and 8 h), using Tri-Carb 2910TR/ Perkin Elmer LAS. (B) RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 0.5 h with CKD712 or MAPK inhibitors. After 0.5 h, cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS and incubated for 8 h. Cells were then harvested and washed 2 times with TBS, followed by sonication in lysis buffer (12 mM NaCl, 75 mM Tris-Cl, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0). The sonicated cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The RAW 264.7 cell lysate was immunobloted with anti-cPLA2 antibody, and assayed for cPLA2 activity. **p < 0.01 compared with no treated-control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared with LPS only-treated group.

DISCUSSION

The cPLA2-induced release of AA is known to play a crucial role in the inflammatory response (Magrioti and Kokotos, 2009) and sepsis (Uozumi et al., 2008). In the present study, we showed that CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced release of AA through inhibition of cPLA2 expression. CKD712 inhibits the LPS- induced inflammatory response through various pathways: inhibition of HMGB1 secretion by inhibiting PI3K and classical PKC (Oh et al., 2011), selective inhibition of VCAM-1 (Tsoyi et al., 2009), and inhibition of HO-1 and JAK-2/STAT-1 (Tsoyi et al., 2008). Although the inhibitory effect of CKD712 on TXA2 (Pyo et al., 2007), iNOS, and COX-2 (Tsoyi et al., 2008) was also reported, whether it regulates cPLA2 as a key enzyme in the inflammatory response remains unknown. In fact, the precise mechanism regarding LPS/TLR signal-induced activation and cPLA2 expression remains unclear. A recent study showed that MAPKs and NF-κB pathways were involved in LPS-induced up-regulation of cPLA2 (Luo et al., 2006). Moreover, MAPKs are reported to mediate both cPLA2 expression, and phosphorylation (Zhi et al., 2007). Several lines of evidence demonstrate that various stimulators beside LPS induce the expression of cPLA2 through MAPK activation. Bradykinin-induced activation of PKC activates ERK, and then induces the expression of cPLA2 (Yang et al., 2005). Induction of cPLA2 and COX-2 by oncogenic Ras is mediated through the JNK and ERK pathway, rather than p38 MAPK (Van Putten et al., 2001).

It is known that cPLA2 can promote the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (McGuirk et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008). However, it is unlikely that the expression levels of cPLA2 change through an NF-κB-mediated autocrine production of a pro-inflammatory cytokine such as TNF-α (Lee et al., 2011). LPS-induced release of AA seems to be a long-term effect in our system, because AA was significantly increased after 4 h. Moreover, the expression of cPLA2 and the activation of NK-κB were significantly increased after 8 h and 4 h, respectively (Figs. 7A and 7B). On the other hand, LPS induced the phosphorylation of MAPKs after 30 min (Fig. 8). Additionally, in this study, we determined that CDK 712 could inhibit perfectly LPS-induced AA release from RAW 264.7 cell even at 10 μM (Fig. 3D) but, protein level of cPLA2 was significantly reduced at > 50 μM of CKD712 (Fig. 5A). Perhaps, in low concentration of CKD712, an additional pathway may regulate AA release not only regulation of cPLA2 expression pathway. In order to verify this hypothesis, we plan some additional experiments recently.

Several studies showed that MAPKs, including p38 MAPK (Leoncini et al., 2006), ERK (Su et al., 2004), and JNK (Casas et al., 2009), also induce cPLA2 phosphorylation. However, our results indicate that phosphorylation of cPLA2 was not observed after 2 h of stimulation with LPS (data not shown). Instead, our study showed that MAPK inhibitors diminished not only LPS-induced release of AA, but also cPLA2 expression, suggesting that MAPKs may mediate the expression of cPLA2.

Despite our use of MAPK inhibitors at different concentrations that can inhibit the expression of cytokines such as IL-2 and TNF-α as applied in studies investigating cPLA2 expression by using NF-κB (Barancik et al., 2001; Bennett et al., 2001; Xin et al., 1999), each of the MAPK inhibitors showed a different effect on LPS-induced AA release. PD98059 at 2 μM, SP 600125 at 110 nM, and SB203580 at 70 nM, could inhibit the phosphorylation of MAPKs (data not shown). That is, SB203580 slightly inhibited LPS-induced release of AA at 1 μM, whereas SP600125 and PD98059 completely inhibited the release at 5 μM and 1 μM after 8 h, respectively (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 9, MAPKs were involved in LPS-induced AA release. Furthermore, CKD712 inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and JNK/SAP, but not p38 MAPK, suggesting that CKD712 could completely inhibit the release of AA by inhibiting the activation of ERK1/2 and SAP/JNK.

The results from this study collectively show that CKD712 inhibited LPS-induced activation of NF-κB by inhibiting ERK1/2 and SAP/JNK, rather than p38 MAPK, thus inhibiting the release of AA through the inhibition of cPLA2 expression. Our findings may provide a rationale for using CKD712 as a potent therapeutic agent for sepsis through its reduction of AA, a precursor to inflammatory mediators such as eicosanoids.

Fig. 1.

Structure of CKD712. (S)-1-α-Naphthylmethyl-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Public Welfare & Safety Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2010-0020844).

REFERENCES

- Barancik M, Bohacova V, Kvackajova J, Hudecova S, Krizanova O, Breier A. SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38-MAPK pathway, is a new reversal agent of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Baron MJ, Perrella MA. Pathobiology of sepsis: are we still asking the same questions? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:129–134. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas J, Meana C, Esquinas E, Valdearcos M, Pindado J, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. Requirement of JNK-mediated phosphorylation for translocation of group IVA phospholipase A2 to phagosomes in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;183:2767–2774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JD, Schievella AR, Nalefski EA, Lin LL. Cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1995;12:83–117. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(95)00012-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieter P, Kolada A, Kamionka S, Schadow A, Kaszkin M. Lipopolysaccharide-induced release of arachidonic acid and prostaglandins in liver macrophages: regulation by Group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2, but not by Group V and Group IIA secretory phospholipase A2. Cell Signal. 2002;14:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy DW, Newson J, Sawmynaden P, Willoughby DA, Croxtall JD. A novel role for phospholipase A2 isoforms in the checkpoint control of acute inflammation. FASEB J. 2004;18:489–498. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0837com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover S, de Carvalho MS, Bayburt T, Jonas M, Chi E, Leslie CC, Gelb MH. Translocation of the 85-kDa phospholipase A2 from cytosol to the nuclear envelope in rat basophilic leukemia cells stimulated with calcium ionophore or IgE/antigen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15359–15367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Lee YS, Lee GW, Lee DH, Ryu JC, Yun-Choi HS, Chang KC. Inhibition of activation of nuclear factor kappaB is responsible for inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by higenamine, an active component of aconite root. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DK, Bonventre JV. Purification of a 100 kDa phospholipase A2 from spleen, lung and kidney: antiserum raised to pig spleen phospholipase A2 recognizes a similar form in bovine lung, kidney and platelets, and immunoprecipitates phospholipase A2 activity. Biochem J. 1993;294:261–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2940261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Kim GY, Kim JH, You HJ, Park YM, Lee HK, Yu HC, Chung SM, Jin ZW, Ko HM, et al. Glutamine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation and protects against endotoxin shock in mouse. Shock. 2006;25:290–294. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000194041.18699.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell R. Robbins Basic Pathology. 8th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lamour NF, Subramanian P, Wijesinghe DS, Stahelin RV, Bonventre JV, Chalfant CE. Ceramide 1-phosphate is required for the translocation of group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26897–26907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Lin CC, Lee IT, Lee HC, Yang CM. Activation and induction of cytosolic phospholipase a(2) by TNF-alpha mediated through Nox2, MAPKs, NF-kappa B, and p300 in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2103–2114. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoncini G, Bruzzese D, Signorello MG. Activation of p38 MAPKinase/cPLA2 pathway in homocysteine-treated platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:209–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CC. Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16709–16712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Dana R, Hazan I, Levy I, Weber G, Smoliakov R, Pesach I, Riesenberg K, Schlaeffer F. Elevated cytosolic phospholipase A(2) expression and activity in human neutrophils during sepsis. Blood. 2000;95:660–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LL, Wartmann M, Lin AY, Knopf JL, Seth A, Davis RJ. cPLA2 is phosphorylated and activated by MAP kinase. Cell. 1993;72:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90666-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo SF, Lin WN, Yang CM, Lee CW, Liao CH, Leu YL, Hsiao LD. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by lipopolysaccharide in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells: involvement of MAPKs and NF-kappaB pathways. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1201–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrioti V, Kokotos G. Phospholipase A2 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;20:1–18. doi: 10.1517/13543770903463905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk SP, Griselli M, Stumper OF, Rumball EM, Miller P, Dhillon R, de Giovanni JV, Wright JG, Barron DJ, Brawn WJ. Staged surgical management of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a single institution 12 year experience. Heart. 2006;92:364–370. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Uozumi N, Ishii S, Kume K, Izumi T, Ouchi Y, Shimizu T. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:42–46. doi: 10.1038/76897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Uozumi N, Aoki-Nagase T, Terawaki K, Ishii S, Tomita T, Yamamoto H, Hashizume K, Ouchi Y, Shimizu T. A potent inhibitor of cytosolic phospholipase A2, arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, attenuates LPS-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L720–726. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00396.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YJ, Youn JH, Min HJ, Kim DH, Lee SS, Choi IH, Shin JS. CKD712, (S)-1-(alpha-naphthylmethyl)-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline, inhibits the lipopolysaccharide-stimulated secretion of HMGB1 by inhibiting PI3K and classical protein kinase C. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1160–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Kang YJ, Park MK, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Hye Sook YC, Shin JS, Lee HW, et al. Enantiomers of higenamine inhibit LPS-induced iNOS in a macrophage cell line and improve the survival of mice with experimental endotoxemia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Hwang IC, Ha N, Lee S, Kim JM, Lee SS, Yu H, Lim IT, You JA, Kim DH. Effects of the antisepsis drug, (S)-1-(alpha-naphthylmethyl)-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (CKD-712), on mortality, inflammation, and organ injuries in rodent sepsis models. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:485–494. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo MK, Kim JM, Jin JL, Chang KC, Lee DH, Yun-Choi HS. Effects of higenamine and its 1-naphthyl analogs, YS-49 and YS-51, on platelet TXA2 synthesis and aggregation. Thromb Res. 2007;120:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riendeau D, Guay J, Weech PK, Laliberte F, Yergey J, Li C, Desmarais S, Perrier H, Liu S, Nicoll-Griffith D, et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, a potent inhibitor of 85-kDa phospholipase A2, blocks production of arachidonate and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by calcium ionophore-challenged platelets. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15619–15624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshak A, Sathe G, Marshall LA. Suppression of monocyte 85-kDa phospholipase A2 by antisense and effects on endotoxin-induced prostaglandin biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25999–26005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena RK, Vallyathan V, Lewis DM. Evidence for lipopolysaccharide-induced differentiation of RAW264.7 murine macrophage cell line into dendritic like cells. J Biosci. 2003;28:129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF02970143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, McClarty G, Dong F, Hatch GM, Pan ZK, Zhong G. Activation of Raf/MEK/ERK/cPLA2 signaling pathway is essential for chlamydial acquisition of host glycerophospholipids. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9409–9416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoyi K, Kim HJ, Shin JS, Kim DH, Cho HJ, Lee SS, Ahn SK, Yun-Choi HS, Lee JH, Seo HG, et al. HO-1 and JAK-2/STAT-1 signals are involved in preferential inhibition of iNOS over COX-2 gene expression by newly synthesized tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid, CKD712, in cells activated with lipopolysacchride. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1839–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoyi K, Kim WS, Kim YM, Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Yun-Choi HS, Chang KC. Upregulation of PTEN by CKD712, a synthetic tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid, selectively inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced VCAM-1 but not ICAM-1 expression in human endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uozumi N, Kita Y, Shimizu T. Modulation of lipid and protein mediators of inflammation by cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha during experimental sepsis. J Immunol. 2008;181:3558–3566. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Putten V, Refaat Z, Dessev C, Blaine S, Wick M, Butterfield L, Han SY, Heasley LE, Nemenoff RA. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by oncogenic Ras is mediated through the JNK and ERK pathways in rat epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1226–1232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Xue H, Xu Q, Zhang K, Hao X, Wang L, Yan G. p38 kinase/cytosolic phospholipase A2/cyclooxygenase-2 pathway: a new signaling cascade for lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6 release in differentiated U937 cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2008;86:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X, Yang N, Faber JE. Platelet-derived growth factor inhibits alpha1D-adrenergic receptor expression in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and ex vivo. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1143–1151. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CM, Lin MI, Hsieh HL, Sun CC, Ma YH, Hsiao LD. Bradykinin-induced p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation and cell proliferation via Src, EGF receptors, and PI3-K/Akt in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:538–546. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi L, Ang AD, Zhang H, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide induces the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines in human monocyte cell line U937 via the ERK-NF-kappaB pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1322–1332. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1006599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SJ, Du GY. Effects of higenamine on the cardio-circulatory system. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2003;28:910–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]