Abstract

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is known to promote tumor migration and invasion. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the TGF-β family expressed in a variety of human carcinoma cell lines. The role of bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP9), the most powerful osteogenic factor, in osteosarcoma (OS) progression has not been fully clarified. The expression of BMP9 and its receptors in OS cell lines was analyzed by RT-PCR. We found that BMP9 and its receptors were expressed in OS cell lines. We further investigated the influence of BMP9 on the biological behaviors of OS cells. BMP9 overexpression in the OS cell lines 143B and MG63 inhibited in vitro cell migration and invasion. We further investigated the expression of a panel of cancer-related genes and found that BMP9 overexpression increased the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 proteins, increased the expression of ID1, and reduced the expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) in OS cells. BMP9 silencing induced the opposite effects. We also found that BMP9 may not affect the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12)/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) axis to regulate the invasiveness and metastatic capacity of OS cells. Interestingly, CXCR4 was expressed in both 143B and MG63 cells, while CXCL12 was only detected in MG63 cells. Taken together, we hypothesize that BMP9 inhibits the migration and invasiveness of OS cells through a Smad-dependent pathway by downregulating the expression and activity of MMP9.

Keywords: BMP9, invasion, migration, MMP9, osteosarcoma

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignant bone tumor arising from bone in children and young adults. Conventional OS is classified into osteoblastic, chondroblastic and fibroblastic OS, according to its histological features (Bielack et al., 2009). OS is highly aggressive and it metastasizes mostly to the lungs and bones (Gill et al., 2013). However, despite the use of aggressive chemotherapeutic treatment strategies, the survival of OS patients has shown limited improvement. The prognosis is very poor, particularly in patients with clinically detectable metastasis at diagnosis or relapsed disease (Wachtel and Schaefer, 2010). Thus, a novel strategy to efficiently inhibit metastasis is highly desirable.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) belong to the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily. To date, more than 20 BMPs have been identified. Several BMPs, including BMP2, BMP4, BMP6, BMP7 and BMP9, have been shown to promote osteogenic differentiation, and recent evidence suggests that BMP9 is probably the most potent inducer (De Biase and Capanna, 2005; Kang et al., 2004; Luu et al., 2007). BMP9 is implicated in a number of physiologic events, including bone morphogenesis, function of the hepatic reticuloendothelial system, hematopoiesis, neuronal differentiation, glucose homeostasis, iron homeostasis and angiogenesis (Chen et al., 2003; David et al., 2007; Lopez-Coviella et al., 2000; Scharpfenecker et al., 2007; Upton et al., 2009). BMP9 exerts its effect by binding to and inducing the formation of heterotetrameric receptor complexes consisting of combinations of type I [activin receptor-like kinase (ALK1-7)] and type II (BMPRII, ActRIIA and ActRIIB) BMP receptors, leading to phosphorylation of the type I receptor and recruitment of downstream signaling restricted Smad proteins (R-Smads, Smads1, 5, and 8). As a result, Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 are activated by BMP9 receptors. Phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 forms a complex with Smad4 and then translocates to the nucleus to directly or indirectly regulate gene transcription (Miyazono et al., 2010; Nohe et al., 2004).

More recently, BMP9 has been demonstrated to play different roles in cancer cells dependent on the tissue type and environment. BMP9 has been shown to inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasiveness of prostate cancer cells and breast cancer cells (Wang et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2008), but to promote the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells (Herrera et al., 2009). However, the role of BMP9 in OS has not been comprehensively explored. In the current study, the expression of BMP9 and its receptors was examined in OS cell lines. We found that BMP9 and all of its receptors were expressed in OS cell lines, and that BMP9 overexpression inhibited OS cell migration and invasion. Conversely, BMP9 silencing induced the opposite effects. Furthermore, BMP9 simultaneously activated the Smad 1/5/8 pathway. By analyzing a panel of cancer-related genes, we found that BMP9 overexpression reduced the expression and activity of MMP9, while BMP9 silencing increased the expression and activity of MMP9 in OS cells. BMP9 did not mediate any significant effect on the expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) and its ligand, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12), which was only detected in MG63 cells. We hypothesize that BMP9 inhibited OS cell migration and invasion by activating the Smads signaling cascade and downregulating the expression and activity of MMP9.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-high glucose (DMEM-HG) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from HyClone. The HEK293 human embryonic kidney cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and the human OS cell lines, 143B and MG63, were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection. Recombinant adenoviruses expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), red fluorescent protein (RFP) or BMP9 (AdGFP, AdRFP, AdBMP9), and the BMP receptor Smad-responsive luciferase reporter, p12xSBE-luc, were generous gifts from Professor T.C. He, Chicago University, USA. Recombinant adenoviruses expressing siRNA targeting BMP9 (AdsiBMP9) with RFP were generated in our laboratory. Matrigel was obtained from Becton-Dickinson. Lipofectamine 2000 and Trizol reagent were purchased from Invitrogen (USA). RT-PCR reagents and SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit were purchased from TaKaRa Biotech (China). Anti-β-actin, anti-Smad1/5/8 and CXCR4 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). Anti-p-Smad1/ 5/8 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (MA). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Zhongshan Golden Bridge (China). Western blotting detection reagents were purchased from the Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (China). BeyoECL was purchased from Millipore. Luciferase assay kit was purchased from Promega. SDF-1α enzyme immunoassay kit was purchased from RayBiotech. Gelatin was obtained from Sigma.

Cell culture

The HEK293 and human OS cell lines, 143B and MG63, were cultured in DMEM-HG supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin G/streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air, and the medium was replaced every 2 days. The HEK293 cell line was used to generate adenoviruses. The experiments were performed using cells from passages 3–5.

Adenovirus infection

The cells were infected with AdBMP9, AdsiBMP9 or the control vectors, AdGFP and AdRFP. A blank control group not infected with adenovirus was also included. After 8–12 h of culture, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM. The fluorescence was then observed 24 h later. The adenovirus-infected cells were used for subsequent experiments.

Wound healing assay

143B and MG63 cells were seeded at densities of 3 × 105 and 3.5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates, respectively. On the following day, the cells were infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9. When the cells formed a confluent monolayer, the monolayers were wounded with pipette tips and the culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium. Wound healing was observed using bright field microscopy and images were captured at 0, 24 and 40 h after wounding.

Transwell motility and invasion assays

Cell motility and invasion assays were performed using 24-well BD Bio-Coat Invasion Chambers without or with Matrigel, respectively. Approximately 7.5 × 104 143B and 1 × 105 MG63 cells, suspended in 0.4 ml serum-free DMEM medium, were added to the upper chamber, and DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After incubation for 24 h, the upper surface of the pore filter was wiped with cotton swabs and cells that penetrated the pore filter were fixed and stained with crystal violet solution. Then, the migrating and invading cell numbers were counted in five randomly selected microscopic fields.

RNA extraction, RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 143B and MG63 cells using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the Reverse Transcriptase M-MLV (RNase H-) kit with random hexamer primers. RT-PCR was performed and PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on agarose gels (2%) and visualized with gold-view (Sbsgene, China). Real-time RT-PCR of MMPs and GAPDH gene expression in each group was performed using the CFX Connect™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) and the SYBR Prime-Script RT-PCR Kit (Perfect Real Time), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCt method. The expression levels of each mRNA were normalized to GAPDH. The primers used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| BMP9 | CTGCCCTTCTTTGTTGTCTT | CCTTACACTCGTAGGCTTCATA |

| ALK1 | GGCTCCCTCTACGACTTTCT | TGGGCAATGGCTGGTTT |

| ALK2 | AGGATTACAAGCCACCG | TACCAGCATTCTTTCATTAG |

| ALK3 | TCTTGGAGGAGTCGTAA | GTAAATGTATAGCTGAGGC |

| ALK4 | GTGGTGATGTGGCTGTGA | CCAGGTGCCATTATCTTTAT |

| ALK5 | CGCAACTCAGTCAACAGG | TGCACAGAAAGGACCCAC |

| ALK6 | AAATGTGGGCACCAAGAAAGA | ACAGGCAACCCAGAGTCATC |

| ALK7 | ATGTTGGGCATCAGTCA | TGGAAGGTGCAGTGTTAT |

| BMPRII | AAATAGCCTGGCAGTGAG | ATGTGACAGGTTGCGTTC |

| ActRIIA | AAACCTGCCATATCTCAC | GCACCCTCTAATACCTCT |

| ActRIIB | GAAGATGAGGCCCACCATTA | GACAGAGGTCACCAGGGAAA |

| ID1 | CGGTCTCATTTCTTCTCG | TCGGTCTTGTTCTCCCTC |

| CXCR4 | ACGCCACCAACAGTCAGA | ACAACCACCCACAAGTCA |

| CXCL12 | TGAGCTACAGATGCCCATGC | TTCTCCAGGTACTCCTGAATCC |

| MMP2 | TGGCAAGGAGTACAACAGC | TGGAAGCGGAATGGAAAC |

| MMP7 | GGAGGAGATGCTCACTTCGAT | AGGAATGTCCCATACCCAAAGA |

| MMP9 | GGGACGCAGACATCGTCATC | TCGTCATCGTCGAAATGGGC |

| GAPDH | CAGCGACACCCACTCCTC | TGAGGTCCACCACCCTGT |

Western blot analysis

Briefly, for protein isolation, 143B and MG63 cells were lysed with RIPA buffer. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes, followed by primary antibody incubation. After washing thrice with TBST, the membranes were incubated with a secondary IgG antibody for 1 h and washed again. The proteins of interest were detected using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Luciferase reporter assay

Exponentially growing cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates and transfected with 0.8 μg per well of BMP receptor Smad-responsive luciferase reporter, p12x SBE-luc, using Lipofectamine 2000. The medium was replaced 4–6 h after transfection. The next day, the cells were infected with AdBMP9 and AdGFP. Twenty-four hours after treatment, the cells were lysed and the cell lysates were collected for luciferase assays.

Immunocytochemical staining

For immunocytochemical staining of CXCR4 in 143B cells, the cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and then permeabilized by incubation in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 10 min. The coverslips were treated with 30% hydrogen peroxide solution at room temperature for 30 min to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. Then, the coverslips were washed in PBS thrice and blocked with normal goat serum at room temperature for 20 min. The cells were immunolabeled with rabbit anti-CXCR4 primary antibody (diluted 1:100 in PBS) at 4°C overnight. In the negative control group, the primary antibody was replaced with PBS. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG at 37°C for 30 min, followed by incubation with streptavidin-HRP conjugate for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were stained with DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin. The slides were then analyzed under a light microscope.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To determine SDF-1α secretion in conditioned medium, exponentially growing cells were plated in 6-well plates and infected with AdBMP9 or AdGFP. 8–12 h after treatment, the medium was replaced with serum-free medium. After incubation for 24 h, the supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C prior to assays. The supernatants were analyzed using the SDF-1α enzyme immunoassay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gelatin zymography

The activities of MMP9 in the conditioned media were determined by gelatin zymography. In brief, the cells were infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 for 12 h, and then the medium was replaced with serum-free medium. After culturing for a further 24 h, the conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 rpm. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay, and 30 μg of total protein from each sample was mixed with SDS sample buffer without β-mercaptoethanol and then electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg/ml gelatin. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 to remove SDS, incubated overnight at 37°C in 200 mM NaCl containing 40 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.6), and stained with 0.5% Coomassie Blue R-250. The presence of gelatinolytic or fibrinolytic activities was identified as transparent bands on a uniform blue background after destaining in 10% methanol and 5% acetic acid in water.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using independent sample Student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 5. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

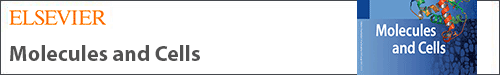

Characterization of BMP receptors in 143B and MG63 cells

To investigate the potential role of BMP signaling in 143B and MG63 cells, we analyzed the expression of seven type I receptors, ALKs 1-7, and three type II receptors, BMPRII, ActRIIA and ActRIIB, by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, in both 143B and MG63 cells, all BMP receptors were readily detected. The efficiency of AdBMP9 and AdsiBMP9 was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that 143B and MG63 cells are competent for responding to BMP signals.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of BMP receptors in 143B and MG63 cells. (A) Total RNA was isolated from the two OS cell lines. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed to assess the expression of the BMP receptors, ALK1-7 and BMPRII, ActRIIA and ActRIIB. (B) The expression of BMP9 in 143B cells and MG63 cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 at the mRNA level. All samples were normalized to GAPDH.

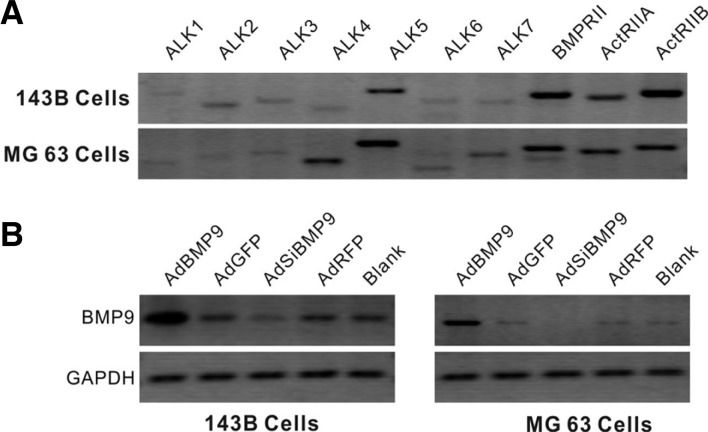

In vitro cell migration and invasion depend on BMP9 expression

To evaluate the effect of BMP9 on metastatic activity, cell migration was analyzed by wound healing and transwell migration assays. The data showed that BMP9 overexpression decreesed the wound closure rate and migrating cell numbers from 170 ± 19.1 to 98 ± 12.9 (P < 0.05) in 143B cells and 64 ± 7 to 40 ± 4.5 (P < 0.05) in MG63 cells compared with the AdGFP group, whereas BMP9 silencing had opposite effects. There was no significant difference between AdGFP or AdRFP and the blank control group (Figs. 2A and 2B). To further analyze the effect of BMP9 on the tumor malignancy of 143B and MG63 cells in vitro, a cell invasion assay was performed. As shown in Fig. 2C, BMP9 overexpression significantly reduced invasion cell numbers from 16.3 ± 0.9 to 9 ± 1.8 (P < 0.05) in 143B cells and from 13 ± 1.2 to 6.3 ± 0.8 (P < 0.05) in MG63 cells compared with the AdGFP group, whereas knockdown of BMP9 in 143B cells significantly increased invasion. These results suggest that BMP9 overexpression can inhibit the migration and invasion of OS cells.

Fig. 2.

In vitro cell migration and invasion depend on BMP9 expression. (A) Cell migration was monitored in a wound healing assay for 24 h in 143B cells and 40 h in MG63 cells. Magnification, ×100. (B) Relative transwell migration by 143B and MG63 cells was examined after incubation for 24 h. *P < 0.05 versus control cells. (C) Relative transwell invasion by 143B cells and MG63 cells was examined after incubation for 24 h. *P < 0.05 versus control cells.

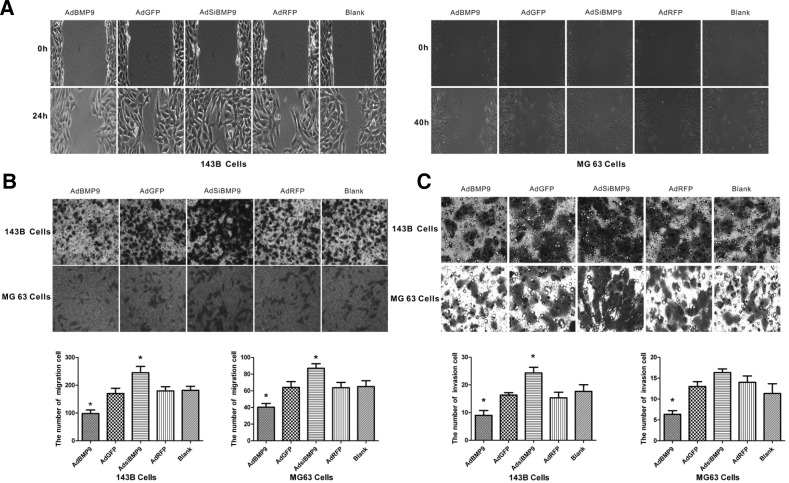

BMP9 overexpression activates the Smad1/5/8 pathway

The phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 downstream of the BMP receptors was analyzed using antibodies that specifically recognize the total and phosphorylated forms of these proteins. Western blotting experiments indicated that BMP9 overexpression increased the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 proteins, and that BMP9 knockdown reduced the phosphorylation of Smad 1/5/8 proteins, while total Smad1/5/8 proteins did not change, in 143B and MG63 cells (Fig. 3A). To further confirm that BMP signals are transduced in 143B and MG63 cells, we then assessed the regulation of transcriptional activity by BMP9 using the BMP-responsive Smads reporter, p12xSBE-Luc. As expected, 2.9-fold and 2.1-fold increases in promoter activity were observed in 143B and MG63 cells, respectively, treated with AdBMP9 compared with cells treated with AdGFP (Fig. 3B). We also investigated whether BMP9 could regulate the expression of its downstream target gene, ID1, by RT-PCR. BMP9 overexpression significantly increased ID1 mRNA expression, whereas knockdown of BMP9 reduced ID1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3C). These data revealed that BMP9 can induce the classical Smad signaling pathway in 143B and MG63 cells to regulate gene transcription.

Fig. 3.

BMP9 overexpression activates the Smad1/5/8 pathway. (A) 143B and MG63 cells were infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 for 24 h, and the total protein was harvested for Western blot analysis using specific antibodies against p-Smad 1/5/8 and Smad 1/5/8 normalized to β-actin. p-Smad 1/5/8 protein levels in the blank group were set as 1. *P < 0.05 versus control cells. (B) 143B and MG63 cells were transfected with p12xSBELuc. Next, cells were infected with AdBMP9. At 24 h post infection, the cells were lysed for luciferase activity assay. (C) 143B and MG63 cells were infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 for 24 h and ID1 levels were analyzed by RT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH. GAPDH expression was used as an internal loading control. ID1 mRNA levels in the blank group were set as 1. *P < 0.05 versus control cells.

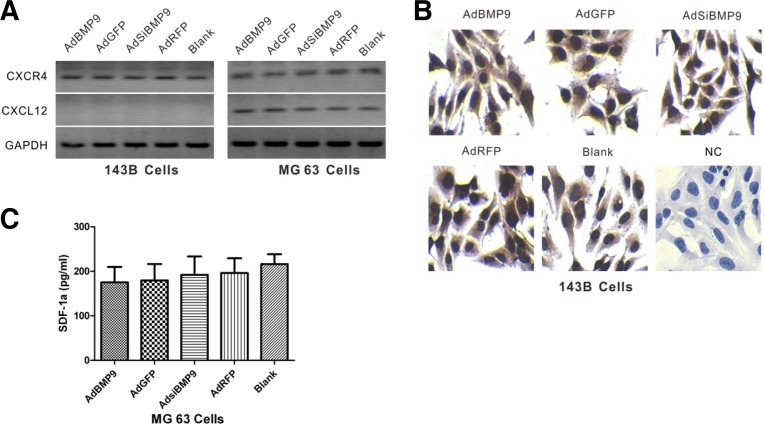

BMP9 does not affect the expression of CXCL12/CXCR4 in 143B and MG63 cells

To explore the mechanism by which BMP9 inhibits OS metastasis, we analyzed the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, which is involved in several aspects of tumor progression including angiogenesis, metastasis and survival. The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis has been shown to be involved in OS tumor progression (Teicher and Fricker, 2010). It was reported that the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling axis enhances the motility of human OS cells (Luo et al., 2008). After infecting 143B and MG63 cells with AdBMP9 or AdSiBMP9, the expression of CXCL12/CXCR4 mRNA by the two OS cell lines was evaluated by RT-PCR, immunostaining and ELISA. We found that the expression of BMP9 did not affect the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Interestingly, CXCL12 was detected in MG63 cells but not in 143B cells, while CXCR4 was expressed in both OS cell lines (Figs. 4A, 4B, and 4C). These results suggest that the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis may not be involved in the inhibition of OS metastasis by BMP9, and this may be one of the reasons for the different metastatic properties of the two cell lines.

Fig. 4.

BMP9 had no effect on the expression of CXCL12/CXCR4 in 143B and MG63 cells. (A) The RNA transcript levels of CXCL12 and CXCR4 were examined in 143B and MG63 cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 by RT-PCR. GAPDH expression was used as an internal loading control. (B) The CXCR4 protein level in 143B cells infected with AdBMPP9 or AdsiBMP9 was determined by immunostaining. (C) The CXCL12 protein level in MG63 cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 was determined by ELISA.

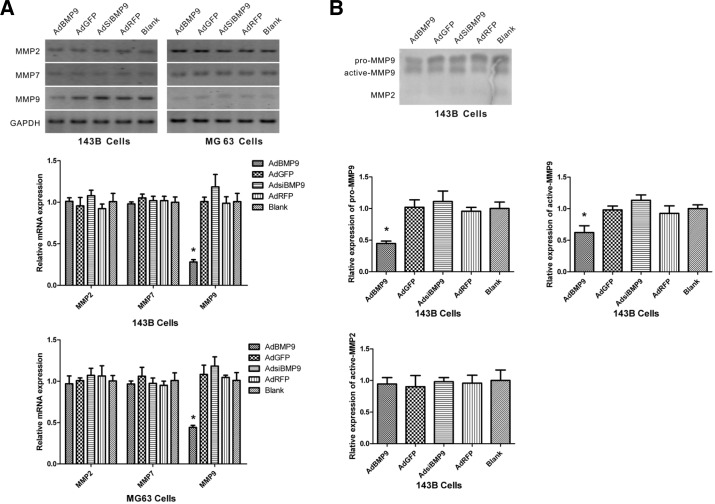

MMP9 but not MMP2 or MMP7 is involved in the inhibition of OS metastasis by BMP9

Cell movement is highly related to the proteolytic activity of MMPs, which regulate the dynamic ECM-cell and cell-cell interactions during migration (Bauvois, 2012; Gialeli et al., 2011). MMPs participate in the invasion of OS cells (Bjornland et al., 2005). To determine whether BMP9 regulates the levels of MMP2, MMP7 and MMP9 mRNAs, RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR was performed. The results showed that BMP9 overexpression markedly reduced the levels of MMP9 mRNA, whereas BMP9 silencing increased the levels of MMP9 mRNA. However, the expression of MMP2 and MMP7 mRNAs was not regulated by BMP9 (Fig. 5A). BMP9 overexpression may inhibit cell migration by downregulating MMP9 expression. To determine the effects of BMP9 on MMP activity, the enzymatic activity of MMPs was measured by gelatin zymographic analysis. The data showed that BMP9 overexpression decreased both the pro- and active forms of MMP9, whereas BMP9 silencing had the opposite effect. MMP2 activity was very weak and did not show any change in response to treatment in 143B cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

MMP9 but not MMP2 or MMP7 was involved in BMP9-inhibited OS metastasis. (A) The RNA transcript levels of MMP2, MMP7 and MMP9 were examined in 143B and MG63 cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 by RT-PCR (top panel) and real-time RT-PCR (bottom panel). GAPDH expression was used as an internal loading control. MMP mRNA levels in the blank group were set as 1. *P < 0.05 versus control cells. (B) The conditioned medium was collected from 143B cells infected with AdBMP9 or AdsiBMP9 for 24 h and analyzed for MMP activity by gelatin zymography. MMP pro- or active levels in the blank group were set as 1. *P < 0.05 versus control cells.

DISCUSSION

OS is the most common primary malignant tumor of the skeleton, and it occurs most frequently at the metaphysis of long bones during the longitudinal growth spurt in children and adolescents (Longhi et al., 2006; Mirabello et al., 2009). Bone tumors accounted for approximately 1,490 deaths and 2,810 new cases in the United States in 2011 (Siegel et al., 2011). Appropriate surgical resection and chemotherapy are the mainstays of treatment (Gorlick and Khanna, 2010; Tan et al., 2009). However, resistance to chemotherapy remains a major mechanism responsible for the failure of OS treatment. BMPs, members of the TGF-β superfamily, have been associated with a number of pathologies, including obesity, diabetes and various vascular diseases in addition to cancer and its related comorbidities (Kim and Choe, 2011). BMP9 was the first BMP to be isolated from the developing mouse liver, and it is the most potent inducer of osteogenic differentiation in MSCs (Luu et al., 2007; Song et al., 1995). More recently, BMP9 has been shown to play different roles in cancers. BMP9 reportedly inhibits the growth, adhesion, invasion and migration of prostate cancer cells, promotes ovarian cancer proliferation through the BMP/Smad signaling pathway, and inhibits the proliferation and invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Herrera et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2008). However, the role of BMP9 in OS cells remains unclear.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of BMP9 on the 143B and MG63 human OS cell lines. It has been reported that BMP signaling enhances invasion and bone metastasis by breast cancer cells through the Smad pathway (Katsuno et al., 2008). Activation of the BMP receptor complex initiates intracellular signal transduction (Chen et al., 2004; Miyazono et al., 2010). Using RT-PCR, we demonstrated that seven type I BMP receptors and three type II receptors were expressed in both 143B and MG63 cells. These results suggest that the binding of BMP9 to these receptors may activate cell signaling and affect OS cell activities. Furthermore, we observed that BMP9 over-expression had a significant inhibitory effect on 143B and MG63 cell migration and invasion, while BMP9 silencing had the opposite effect. These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown an inhibitory effect of BMP9 on the migration of prostate cancer and breast cancer cells (Wang et al., 2011; Ye et al., 2008). The response to BMP9, however, is not uniform among all cancers. BMP9 has been shown to trigger epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Li et al., 2013), and to be both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic, which likely reflects its complex interactions in developmental processes. Thus, the biologic response of cancer cells to BMP9 may depend not only on dosage, type of cell or tissue and the tumor microenvironment, but also on the presence of other factors that are not yet defined.

Smads are central mediators of BMP signaling that are activated by type I receptor kinases. To further explore whether BMP9 signaling pathways were functional in these two cell lines, the total and phosphorylated forms of Smad1/5/8 were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies that specifically recognize the total and phosphorylated forms of Smad1/5/8. We also analyzed the expression of ID1, which is a BMP target gene, by RT-PCR. Our results indicated that BMP9 overexpression induced the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 in these two cell lines. Furthermore, BMP9 overexpression activated the BMP receptor, Smad-responsive luciferase reporter activity, and increased the expression of its target gene, ID1. Taken together, these data demonstrate that BMP9 overexpression activates the Smad1/5/8 pathway.

It has been reported that the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is involved in the metastatic process in OS cells. CXCL12/CXCR4 enhanced the migration of human OS cells (Luo et al., 2008). CXCR4 is useful as a prognostic factor and as a predictor of potential metastatic development in OS (Laverdiere et al., 2005). The CXCR4/SDF-1 axis was involved in the metastatic process in OS cells in a mouse model (Perissinotto et al., 2005). We also showed that BMP9 expression is related to OS tumor progression. Based on these results, we proposed a hypothesis that the acquisition of invasiveness in OS cells by BMP9 inhibition may be associated with the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. We found that the expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 was not affected by either overexpression or knockdown of BMP9. Thus, our results demonstrate that BMP9 may not affect the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis to regulate the invasion and metastasis of OS cells. Interestingly, we found that CXCR4 was expressed in the two cell lines, but CXCL12 mRNA was only detected in MG63 cells and not in 143B cells, which might explain the different behaviors of these tumor cells.

It has been suggested that Disuffiram suppresses OS cell invasion by inhibiting MMP2 and MMP9 expression (Cho et al., 2007). BMP2 enhances tumor metastasis in gastric cancer in part by induction of MMP-9 activity (Kang et al., 2011). It remains to be determined whether MMPs are regulated by BMP9. Here, we showed that BMP9 overexpression reduced the level of MMP9 transcripts and MMP9 enzymatic activity, while BMP9 silencing had the opposite effects. However, BMP9 overexpression had no effect on MMP2 and MMP7 expression, or MMP2 enzymatic activity. However, whether MMP9 is critical for the inhibition of OS cell invasion by BMP9 needs to be further investigated.

In conclusion, this study found that BMP9 overexpression in OS cell lines reduced their migration and invasiveness, while BMP9 silencing had the opposite effect. Moveover, BMP9 overexpression activated the Smad1/5/8 pathway and downregulated the expression and activity of MMP9. Future studies should focus on defining whether the Smad1/5/8 pathway and MMP9 are required for the inhibition of OS cell invasion by BMP9, which may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for OS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our kind thanks to Dr. T.-C. He of The University of Chicago Medical Center for providing the adenoviruses. This work was supported by grant 30872770 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC3087 2770), by grant 31200971 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC31200971), by the Natural Science Foundation Project of CQ CSTC (CSTC, 2011BB5131) and by the National Ministry of Education Foundation of China (KJ120327).

REFERENCES

- Bauvois B. (2012). New facets of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 as cell surface transducers: outside-in signaling and relationship to tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 1825, 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielack S, Carrle D, Casali PG, Group EGW. (2009). Osteosarcoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 20Suppl 4137–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornland K, Flatmark K, Pettersen S, Aaasen AO, Fodstad O, Maelandsmo GM. (2005). Matrix metalloproteinases participate in osteosarcoma invasion. J Surg Res. 127, 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Grzegorzewski KJ, Barash S, Zhao Q, Schneider H, Wang Q, Singh M, Pukac L, Bell AC, Duan R, et al. (2003). An integrated functional genomics screening program reveals a role for BMP-9 in glucose homeostasis. Nat Biotechnol. 21, 294–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. (2004). Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 22, 233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Lee TS, Park JB, Park KK, Choe JY, Sin DI, Park YY, Moon YS, Lee KG, Yeo JH, et al. (2007). Disuffiram suppresses invasive ability of osteosarcoma cells via the inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression. J Biochem Mol Biol. 40, 1069–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, Feige J-J, Bailly S. (2007). Identification of BMP9 and BMP10 as functional activators of the orphan activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) in endothelial cells. Blood 109, 1953–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biase P, Capanna R. (2005). Clinical applications of BMPs. Injury 36Suppl 3S43–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. (2011). Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 278, 16–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J, Ahluwalia MK, Geller D, Gorlick R. (2013). New targets and approaches in osteosarcoma. Pharmacol Ther. 137, 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlick R, Khanna C. (2010). Osteosarcoma. J Bone Miner Res. 25, 683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera B, van Dinther M, ten Dijke P, Inman GJ. (2009). Autocrine bone morphogenetic protein-9 signals through activin receptor-like kinase-2/Smad1/Smad4 to promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 69, 9254–9262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Q, Sun MH, Cheng H, Peng Y, Montag AG, Deyrup AT, Jiang W, Luu HH, Luo J, Szatkowski JP, et al. (2004). Characterization of the distinct orthotopic bone-forming activity of 14 BMPs using recombinant adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. Gene Ther. 11, 1312–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MH, Oh SC, Lee HJ, Kang HN, Kim JL, Kim JS, Yoo YA. (2011). Metastatic function of BMP-2 in gastric cancer cells: The role of PI3K/AKT, MAPK, the NF-kappa B pathway, and MMP-9 expression. Exp Cell Res. 317, 1746–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuno Y, Hanyu A, Kanda H, Ishikawa Y, Akiyama F, Iwase T, Ogata E, Ehata S, Miyazono K, Imamura T. (2008). Bone morphogenetic protein signaling enhances invasion and bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through Smad pathway. Oncogene 27, 6322–6333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Choe S. (2011). BMPs and their clinical potentials. BMB Rep. 44, 619–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverdiere C, Hoang BH, Yang R, Sowers R, Qin J, Meyers PA, Huvos AG, Healey JH, Gorlick R. (2005). Messenger RNA expression levels of CXCR4 correlate with metastatic behavior and outcome in patients with osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 11, 2561–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Gu X, Weng H, Ghafoory S, Liu Y, Feng T, Dzieran J, Li L, Ilkavets I, Kruithof-de Julio M, et al. (2013). Bone morphogenetic protein-9 induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 104, 398–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhi A, Errani C, De Paolis M, Mercuri M, Bacci G. (2006). Primary bone osteosarcoma in the pediatric age: State of the art. Cancer Treat Rev. 32, 423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Coviella I, Berse B, Krauss R, Thies RS, Blusztajn JK. (2000). Induction and maintenance of the neuronal cholinergic phenotype in the central nervous system by BMP-9. Science (New York, N.Y.) 289, 313–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Chen J, Song W-X, Tang N, Luo J, Deng Z-L, Sharff KA, He G, Bi Y, He B-C, et al. (2008). Osteogenic BMPs promote tumor growth of human osteosarcomas that harbor differentiation defects. Lab Invest. 88, 1264–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu HH, Song W-X, Luo X, Manning D, Luo J, Deng Z-L, Sharffl KA, Montag AG, Haydon RC, He T-C. (2007). Distinct roles of bone morphogenetic proteins in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Orth Res. 25, 665–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. (2009). Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer 115, 1531–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. (2010). Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 147, 35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohe A, Keating E, Knaus P, Petersen NO. (2004). Signal transduction of bone morphogenetic protein receptors. Cell Signal 16, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto E, Cavalloni G, Leone F, Fonsato V, Mitola S, Grignani G, Surrenti N, Sangiolo D, Bussolino F, Piacibello W, et al. (2005). Involvement of chemokine receptor 4/stromal cell-derived factor 1 system during osteosarcoma tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 11, 490–497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharpfenecker M, van Dinther M, Liu Z, van Bezooijen RL, Zhao Q, Pukac L, Lowik CWGM, ten Dijke P. (2007). BMP-9 signals via ALK1 and inhibits bFGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 120, 964–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. (2011). Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 61, 212–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Celeste AJ, Kong FM, Jirtle RL, Rosen V, Thies RS. (1995). Bone morphogenetic protein-9 binds to liver cells and stimulates proliferation. Endocrinology 136, 4293–4297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ML, Choong PFM, Dass CR. (2009). Osteosarcoma: conventional treatment vs gene therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 8, 106–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher BA, Fricker SP. (2010). CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 16, 2927–2931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton PD, Davies RJ, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. (2009). Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and activin type II receptors balance BMP9 signals mediated by activin receptor-like kinase-1 in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 284, 15794–15804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtel M, Schaefer BW. (2010). Targets for cancer therapy in childhood sarcomas. Cancer Treat Rev. 36, 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Feng H, Ren W, Sun X, Luo J, Tang M, Zhou L, Weng Y, He T-C, Zhang Y. (2011). BMP9 inhibits the proliferation and invasiveness of breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 137, 1687–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Kynaston H, Jiang WG. (2008). Bone morphogenetic protein-9 induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells, the role of prostate apoptosis response-4. Mol Cancer Res. 6, 1594–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]