Abstract

Ambulatory electroencephalogram has been used for differentiating epileptic from nonepileptic events, recording seizure frequency and classification of seizure type. We studied 100 consecutive children prospectively aged 11 days to 16 years that were referred for an ambulatory electroencephalogram to a regional children's hospital. Ambulatory electroencephalogram was clinically useful in contributing to a clinical diagnosis in 71% of children who were referred with a range of clinical questions. A diagnosis of epileptic disorder was confirmed by obtaining an ictal record in 26% and this included 11 children that had previously normal awake and or sleep electroencephalogram. We recommend making a telephone check of the current target event frequency and prioritising those with typical events on most days in order to improve the frequency of recording a typical attack.

Keywords: Ambulatory electroencephalogram, audit, children

Introduction

Prolonged ambulatory electroencephalogram (AEEG) using a four-channel cassette recorder was first described in 1975.[1] It can be used to determine the focus of a seizure, to quantify the number of seizure discharges in a given period, to identify particular patterns of interictal or barely/subclinical “epileptic” activity, for example, continuous spike-wave in slow-wave sleep (CSWS) or electrical status epilepticus during sleep (ESES), and may help in differentiating between epileptic and nonepileptic events. It has the advantage of monitoring electroencephalogram (EEG) as the patients go about their normal activity including sleep and it can evaluate potential precipitating factors. Overall, clinical usefulness of AEEG in children has varied in different studies from 28% to 90%.[2,3,4]

Optimal duration of recording and the ideal patient selection to maximize its potential have not been well-established in children.

This prospective clinical audit was undertaken to assess the clinical usefulness of AEEG in confirming or rejecting the diagnosis of epileptic seizures and related disorders in an unselected group of children referred to a regional children's hospital. We hoped to ascertain the optimal duration of recording and improve patient selection.

Materials and Methods

We studied 100 consecutive children prospectively aged 11 days to 16 years that were referred for AEEG to a regional children's hospital. The referrals were accepted from paediatric neurologists and pediatricians practising other specialities including psychiatrists and neonatologists. The recordings were undertaken using an eight channel Oxford Medical system with the international 10-20 electrode placement system in the first 50 patients and in the next 50 patients, an 11 electrode and electrocardiogram channel loom digital system was used as it became available. Antiepileptic medication was not altered for the purpose of the recording. The duration of the recordings varied from 24-72 h.

The patient or observer, for example, the parent, pressed an event button during target events, thought to be possibly epileptic or during other events that might produce EEG artefact, such as electrode disconnection. A standard diary form was completed noting the date and time and nature of all such events.

A telephone check of the typical target event frequency was made, during the second half of the audit, within 7 days of the proposed AEEG date. The frequency of target events was based on parent's or carer's estimate and a typical frequency of at least 1 per day was chosen as adequate. Children referred for AEEG investigation of suspicious events occurring less often were deferred and the referring physician informed.

Ictal EEG demonstrating paroxysmal abnormalities: generalized spike and slow wave or focal, rhythmic slow wave activity was considered to be epileptic.

Results

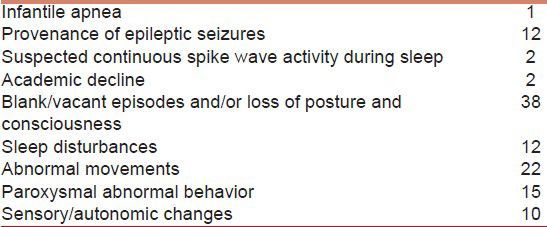

The sources of referral were shown in Table 1 and the reasons for referral in Table 2.

Table 1.

Source of referral for ambulatory electroencephalogram

Table 2.

Reasons for referral for ambulatory electroencephalogram

A total of 19% had more than one reason for referral. Most were undertaken to elucidate events, two were to look for CSWS or ESES and two were because of declining school performance.

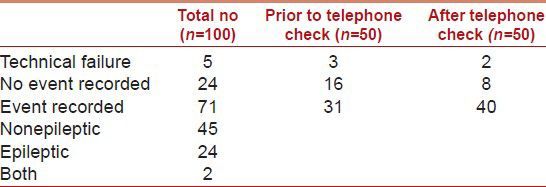

A total of 16 children of the first 50 had no target event recorded. Subsequently, after telephone checks were introduced (see above), only 8 of the next 50 had no target events recorded.

Table 3 shows the outcome of the AEEG recordings in the study population.

Table 3.

Outcome of ambulatory electroencephalogram

Among the 100 children, previous EEG results were available in 88, including 26 sleep EEG records, 1 videotelemetry, and 3 previous AEEGs.

36/88 children had generalized or focal epileptic discharges in their previous records.

Of the 26 children whose events or disorders were confirmed to be epileptic by AEEG, previous EEGs had demonstrated epileptiform abnormalities in 15 and no epileptiform abnormalities in 11.

Of the 45 children whose events or disorders were found to be nonepileptic by AEEG, previous EEGs had demonstrated no epileptiform abnormalities in 30 and epileptiform abnormalities in 9. Six previous EEGs were unavailable for review.

A clear answer to the clinical question was, therefore, provided in 71/100 cases.

A typical target event was recorded in 62% of the first 50 patients and in 80% of the next 50 patients.

Discussion

AEEG has been used for various purposes including differentiating epileptic from nonepileptic events, recording seizure frequency and classification of seizure type.[2,3] One study also reported its application in adults when under reporting of seizure frequency was suspected, to optimize the treatment.[5] It has also been used to help in identifying patients at low risk of recurrent seizures, among the patients presenting with infrequent seizures prior to drug treatment.[6] It has also been used to quantify paroxysmal discharges in patients with typical absence epilepsies by a limited recording over 8 h.[7]

88% of the children in our study underwent AEEG recording to help the differential diagnosis of a paroxysmal clinical event occurring in the awake or sleep state. The frequency of this indication was similar to that reported by Olson.[2] The clinical question that initiated the referral to AEEG could be answered in 71% of the patients and epileptic events were confirmed in 26% by AEEG. A total of 45% of the events/EEGs recorded had no electrographic epileptic correlates and a diagnostic opinion of nonepileptic events or disorders was offered to the referring clinician.

The frequency of success in differentiating epileptic from nonepileptic events varied from 52% to 89% in the other reported pediatric studies.[2,3,4] However, several theoretical problems limit the clinical utility of AEEG including the absence of a close correlation between AEEG and video-EEG. Some focal seizures responsible for behavioral and motor attacks, unresponsive stares or abnormal movements during sleep may not be recorded by the surface electrodes used in AEEG, for example, classically frontal lobe seizures may produce no changes on scalp EEG.

The use of combined ambulatory EEG and video recording of hospital in-patients has been reported by Shihabuddin et al.,[8] who used a time and date generator to synchronize the ambulatory cassette EEG recording with the video recording. A similar approach may be possible in out-patients.

The studies that reported the varying clinical value of AEEG in differentiating between epileptic and nonepileptic events did so by accepting the clinical diagnosis, and, in some, the clinical course of the patients, as the standard. No study, including our audit used video telemetry as the reference standard for comparing the outcomes of AEEG. Hence, a small number of patients may be misdiagnosed as having nonepileptic events due to absence of ictal abnormalities in the recordings using surface electrodes only. This was evident from the observations of Aminoff[9] in 1987. They examined AEEG findings of children who were diagnosed to have definitely epileptic or nonepileptic attacks and found that no electrographic accompaniments were present in some in “epileptic” attacks. They suggested that the more important role of AEEG was to reject a diagnosis of nonepileptic attacks by demonstration of electrographic seizure activity accompanying typical clinical events.

In our audit, when deciding the outcome of AEEG we accepted the attacks as likely to be nonepileptic if the ictal recordings had no electrographic accompaniments.

AEEG contributed to a change in the clinical diagnosis or management in 71% of our patients as compared to 29%, 90%, and 89%, respectively in the studies by Saravanan et al., Olson et al., and Foley et al. This may be due to variation in patient selection, the referral patterns, and indications and the duration of recording.

The criteria for selecting patients that had AEEG recordings varied from having their typical attacks on at least 3 days of a week to having attacks on most days and this information was not provided in some studies. It is suggested that selection of children with frequent episodes is an important factor associated with a higher chance of capturing the habitual target event.[10] However, a diagnostic opinion was reached in the highest percentage of children in the study by Olson et al., when the criteria of typical attacks on at least 3 days of a week were used.

In our study one or more typical target event was recorded in 71%. In the first half of the study, 16/50 had no events and this decreased to 8/50 in the second half when a telephone check of the event frequency was made in the week prior to the AEEG recording and only children with attacks typically every day were included. Our observations as well as those of Olson et al., suggest that to maximize the frequency of recording target events, only those with typical events on most days and at least on 3 or more days of a week should have an AEEG recorded.

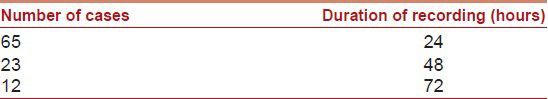

In the 71 patients that had their typical clinical events successfully recorded on AEEG, they were recorded within 24 h in 65 [Table 4]. This suggested that AEEG recordings for longer than 24 h may not be routinely necessary if patient selection can be optimised.

Table 4.

Ambulatory electroencephalogram recording duration

AEEG monitoring allows for long-term, mobile electroencephalographic recordings in children. It has the advantage that patients can go about their normal activity including sleep in their usual surroundings which can be very helpful, especially in children with previously normal awake and or sleep EEGs. Ambulatory EEG recordings in correctly selected cases can provide important additional information especially in confirming the diagnosis of epilepsy and can be an investigation to consider in the diagnostic chain prior to referral for a prolonged video-EEG.[11]

Conclusion

AEEG was clinically useful in contributing to a clinical diagnosis in 71% of children who were referred with a range of clinical questions. A diagnosis of epileptic disorder was confirmed by obtaining an ictal record in 26% and this included 11 children that had previously normal awake and or sleep EEGs. We recommend making a telephone check of the current target event frequency and prioritising those with typical events on most days in order to improve the frequency of recording a typical attack. Recording duration of 24 h should be sufficient in the majority of children referred for AEEG.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ives JR. 4-channel 24 hour cassette recorder for long-term EEG monitoring of ambulatory patients. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1975;39:88–92. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(75)90131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson DM. Success of ambulatory EEG in children. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:158–61. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saravanan K, Acomb B, Beirne M, Appleton R. An audit of ambulatory cassette EEG monitoring in children. Seizure. 2001;10:579–82. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2001.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley CM, Legido A, Miles DK, Chandler DA, Grover WD. Long-term computer-assisted outpatient electroencephalogram monitoring in children and adolescents. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:49–55. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatum WO, 4th, Winters L, Gieron M, Passaro EA, Benbadis S, Ferreira J, et al. Outpatient seizure identification: Results of 502 patients using computer-assisted ambulatory EEG. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:14–9. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curless RG, Ramsay RE, Katz DA, Gadia CA, Sheehan KA. Ambulatory EEG recordings in children with infrequent seizures. Pediatr Neurol. 1990;6:184–5. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90060-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Feo MR, Mecarelli O, Ricci G, Rina MF. The utility of ambulatory EEG in typical absence seizures. Brain Dev. 1991;13:223–7. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shihabuddin B, Abou-Khalil B, Fakhoury T. The value of combined ambulatory cassette-EEG and video monitoring in the differential diagnosis of intractable seizures. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1452–7. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aminoff MJ, Goodin DS, Berg BO, Compton MN. Ambulatory EEG recordings in epileptic and nonepileptic children. Neurology. 1988;38:558–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LS, Mitchell WG, Horton EJ, Snead OC., 3rd Clinical utility of video-EEG monitoring. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;12:220–4. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(95)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González de la Aleja J, Saiz Díaz RA, Martín García H, Juntas R, Pérez-Martínez D, de la Peña P. The role of ambulatory electroencephalogram monitoring: Experience and results in 264 records. Neurologia. 2008;28:583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]