Abstract

Intracranial tuberculomas continue to be a serious complication of central nervous system tuberculosis. Multiple central nervous system tuberculoma is commonly associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The development of intracranial tuberculomas has been thought to be caused by hematogenous spread of tubercle bacilli on the surface of brain parenchyma from the primary site of infection. Here, we describe the case of a 5-year-old male child with severe protein energy malnutrition (Marasmus) having large cervical lymphadenopathy and severe nutritional rickets with deformity at presentation. The child developed convulsions 20 days after initiation of antituberculous drugs, and neuroimaging confirmed multiple miliary tuberculomas of brain as primary etiology for the convulsions.

Keywords: Disseminated tuberculosis, miliary tuberculoma, rickets

Introduction

There are various clinical and radiological presentations of central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis. Common syndromes described in literature include tuberculous meningitis, solitary tuberculoma involving any part of the central nervous system (cerebral cortex, cerebellar hemispheres, brain stem, and spinal cord), and multiple tuberculomas of the brain. However, the disseminated or miliary brain tuberculosis is an uncommon presentation in children, and multiple tuberculoma of brain is generally seen in immunodeficient seropositive patients. Here, we describe the case of a malnourished child with contact history of tuberculosis to mother, presenting with large cervical lymphadenopathy and nutritional rickets. He developed convulsion due to a disseminated multiple miliary neurotuberculoma within few weeks of starting on antituberculosis treatment.

Case Report

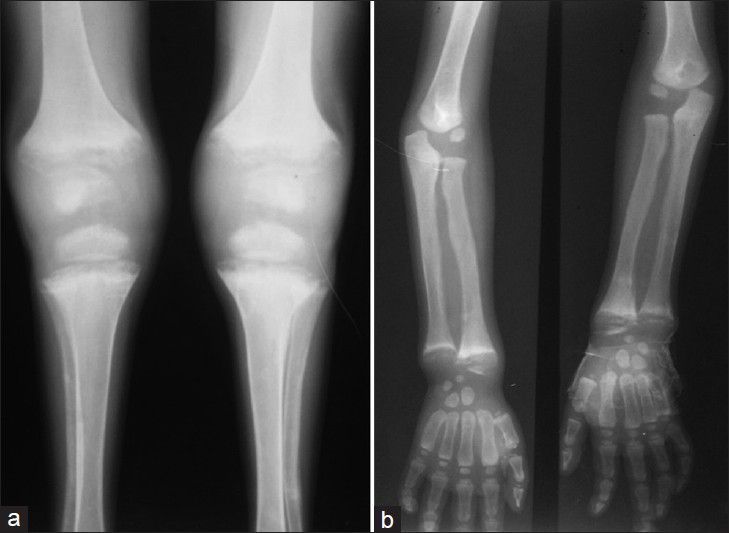

A 5-year-old marasmic male child was referred to our institute for multiple lymphadenopathy. His mother in the same household had pulmonary tuberculosis. On admission, the child had no history of cough, dyspnea or night sweats. However, he was lethargic and unable to stand or sit without support. His general examination was quite remarkable for the evidence of severe protein energy malnutrition (PEM) and rickets. He had marked pallor, generalized xerosis, crusted lesions with boil on the lower back, and hyperpigmented friction dermatosis on buttocks. His crawling movement was further complicated by valgus deformity of legs due to nutritional rickets. Cervical [Figure 1] and groin examination showed multiple matted lymph nodes forming a large cervical and inguinal lymphadenopathy. His ocular examination revealed nebular keratopathy in both eyes. His initial evaluation at the previous institute did not reveal any malignancy as a possible etiology for large cervical and inguinal lymphadenopathy. His detailed clinical neurological evaluation did not reveal any positive findings. Hematological investigation revealed severe anemia (Hemoglobin - 7.3 gm/dl), leukocytosis (Total Leukocytes Count - 15,700/mm3; 84% neutrophils, 12% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, and 1% eosinophils), and mild thrombocytopenia (87,000/mm3). Biochemical investigation for rickets showed hypocalcemia (serum calcium - 6.31 mg/dl), normal phosphate (serum phosphate - 4 mg/dl), higher alkaline phosphate - 310, and low Serum 25 (OH) D - 8 ng/ml. He was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) test; Mantoux test was also negative. The chest X-ray revealed miliary Koch's infiltration with a widening of the costochondral junction of the ribs due to rickets in the bony thorax [Figure 2]. Abdominal and thoracic ultrasound revealed mild hepatomegaly, mild splenomegaly, and enlarged mesenteric, inguinal, peripancreatic, celiac axis, periportal, and bilateral iliac lymph nodes. Corroborative radiological evaluation for rickets (X-ray both knee and wrist joint) showed metaphyseal widening with splaying and fraying of epiphysis and changes related to osteoporosis, and pencil line thinning of the epiphyseal cortex, suggesting rickets [Figure 3]. Fine needle aspiration cytology of cervical lymph node showed features of tuberculous lymphadenitis with the presence of acid-fast bacilli.

Figure 1.

Showing (a and b) large cervical lymphadenopathy and (c) deformity of legs due to rickets

Figure 2.

Chest X-ray showing miliary Koch's infiltration with rickets-like changes in the bony thorax

Figure 3.

X-ray (a) both knee and (b) wrist joint showing rickets-like changes

Antituberculosis therapy including Streptomycin injection (according to CAT-1 of the National Tuberculosis Control Program) and oral steroids were started. Cytology report confirmed the Koch's etiology. Severe PEM and vitamin deficiency were aggressively managed in the hospital with supervised high protein diet and oral therapeutic supplementation of Vitamin A and Vitamin D with calcium. During 2 weeks of observation in the pediatric ward, the child recovered gradually and was discharged home with oral medicines. Within 3 weeks of discharge, the patient presented again to the pediatric intensive care unit with generalized tonic-clonic convulsions. There was no focal neurological sign on examination. The computed tomography (CT) scan of brain revealed multiple small tuberculomas in the brain parenchyma scattered like millets in the cerebral hemispheres, bilateral cerebellum, and brain stem [Figure 4]. Few of them were conglomerate in the left cerebellum, right parietal region, and pons with periventricular hypodensity. Anticonvulsant therapy was started and Streptomycin and steroid were added to the chemotherapy. Afterward, the child was symptom free.

Figure 4.

CT scan of brain showing multiple small tuberculomas in brain parenchyma scattered like millets

Discussion

Tuberculosis of the central nervous system can be present in many different clinical and radiological patterns, with disseminated or miliary brain tuberculomas as a rare presentation.[1] A study by Garg et al. demonstrated that miliary pulmonary tuberculosis is associated with various complications in the central nervous system, of which tuberculous meningitis occurred most frequently and is often complicated by cerebral tuberculoma formation.[2] Tuberculomas develop following hematogenous dissemination of bacilli from an infection elsewhere in the body, usually the lung.[3,4] Paradoxical enlargement of cerebral tuberculomas or development of new ones has been noted during the treatment of miliary tuberculosis or tuberculous meningitis. This paradoxical development of tuberculoma during therapy is recognized as a rare response to treatment of the disease, and is thought to have the same mechanism as paradoxical responses of other tissues such as lymph nodes and lung.[5] The occurrence of paradoxical development of tuberculomas during therapy is presumably due to the interplay between the host's immune responses and direct effects of mycobacterium products.[6,7,8,9] The treatment of paradoxically enlarged tuberculomas is also controversial. Hejazi et al.,[10] in their study of 34 cases, recommended not changing the antituberculous drug regime. They advocated systemic dexamethasone as an adjuvant therapy for 4-8 weeks. Corticosteroids are beneficial in patients with increased intracranial pressure or severe neurological symptoms and, in most patients, surgical treatment is not necessary. Hence, paradoxical development of tuberculomas during chemotherapy usually does not represent a failure of antituberculous therapy and continuation of antituberculous therapy, with or without the addition of steroids, can usually achieve a complete resolution of the tuberculomas.[11] However, surgical treatment may be necessary in some lesions that fail medical treatment or in those with larger lesions located superficially.[12]

Multiple (CNS) tuberculoma is commonly associated with the HIV infection.[13] The patient reported here, though is seronegative for HIV infection, suffered disseminated miliary tuberculosis of lungs and brain. The paradoxical immune response similar to an immunodeficient state is probably due to severe malnutrition and deficiency of essential micronutrient and vitamins. The case reported here may also be considered an immunodeficient host because of the associated severe malnutrition. Children with malnutrition show a high incidence of deranged cellular immunity.[14] Protein deprivation may result in impaired DNA synthesis and atrophy of both the thymus and lymphoid tissue. A correlation has been shown between the degree of impairment of tests of cellular immunity and the severity of malnutrition. Severe nutritional deprivation leads to a deficiency of low-molecular-weight lymphocyte growth factors, which may contribute to immunodeficiency associated with the disease.[15] There is a strong association of decreased serum 25D concentrations and increased severity and/or susceptibility to tuberculosis infection. Williams et al.[16] determined the vitamin D status of 64 children infected with tuberculosis, and 86% of their patients were found to have inadequate vitamin D stores.

Multiple tuberculoma of brain is a well described entity in the literature in adult patients. Our case is that of the youngest child with an immunodeficiency due to severe malnutrition with miliary brain tuberculomas and multiple lymph nodes involvement.

Conclusion

Miliary brain tuberculomas is extremely rare and more commonly reported in seropositive patients with miliary pulmonary tuberculous infection and those with immunodeficiency due to HIV. Our case report highlights a seronegative child with miliary tuberculosis of the brain and lung parenchyma and multiple lymphadenitis. Severe PEM and advanced nutritional rickets constitute a compromised immune status that can facilitate the dissemination of mycobacterial infection as in seropositive patients even after appropriate antituberculous treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Alkhani A, Al-Otaibi F, Cupler EJ, Lach B. Miliary tuberculomas of the brain: Case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:411–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg RK, Sharma R, Kar AM, Kushwaha RA, Singh MK, Shukla R, et al. Neurological complications of miliary tuberculosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:188–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J, Ling C, Kosmalski MM, Hulseberg P, Schreiber HA, Sandor M, et al. Intracerebral mycobacterium bovis bacilli calmette-guerin infection-induced immune responses in the CNS. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;213:112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rock RB, Olin M, Baker CA, Molitor TW, Peterson PK. Central nervous system tuberculosis: Pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:243–61. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onwubalili JK, Scott GM, Smith H. Acute respiratory distress related to chemotherapy of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis: A study of two cases and review of the literature. Q J Med. 1986;59:599–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afghani B, Lieberman JM. Paradoxical enlargement or development of intracranial tuberculomas during therapy: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1092–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang AB, Grimwood K, Harvey AS, Rosenfeld JV, Olinsky A. Central nervous system tuberculosis after resolution of miliary tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:519–23. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199806000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers ST, Hendrickse WA, Record C, Rudge P, Smith H. Paradoxical expansion of intracranial tuberculomas during chemotherapy. Lancet. 1984;2:181–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gropper MR, Schulder M, Duran HL, Wolansky L. Cerebral tuberculosis with expansion into brainstem tuberculoma. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:927–31. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.6.0927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hejazi N, Hassler W. Multiple intracranial tuberculomas with atypical response to tuberculostatic chemotherapy: Literature review and a case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139:194–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01844751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai MH, Huang YC, Lin TY. Development of tuberculoma during therapy presenting as hemianopsia. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:360–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhargava S, Tandon PN. Intracranial tuberculomas: A CT study. Br J Radiol. 1980;53:935–45. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-53-634-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kioumehr F, Dadsetan MR, Rooholamini SA, Au A. Central nervous system tuberculosis: MRI. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:93–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00588067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geefhuysen J, Rosen EU, Katz J, Ipp T, Metz J. Impaired cellular immunity in kwashiorkor with improvement after therapy. Br Med J. 1971;4:527–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5786.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beatty DW, Dowdle EB. Deficiency in kwashiorkor serum of factors required for optimal lymphocyte transformation in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979;35:433–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams B, Williams AJ, Anderson ST. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in children with tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:941–2. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31817525df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]