Abstract

Emergency post-coital contraception (EC) is an effective method of preventing pregnancy when used appropriately. EC has been available since the 1970s, and its availability and use have become widespread. Options for EC are broad and include the copper intrauterine device (IUD) and emergency contraceptive pills such as levonorgestrel, ulipristal acetate, combined oral contraceptive pills (Yuzpe method), and less commonly, mifepristone. Some options are available over-the-counter, while others require provider prescription or placement. There are no absolute contraindications to the use of emergency contraceptive pills, with the exception of ulipristal acetate and mifepristone. This article reviews the mechanisms of action, efficacy, safety, side effects, clinical considerations, and patient preferences with respect to EC usage. The decision of which regimen to use is influenced by local availability, cost, and patient preference.

Keywords: emergency contraception, levonorgestrel, intrauterine device, emergency contraceptive pills

Introduction

Approximately forty percent of all pregnancies worldwide are unintended, with higher unintended pregnancy rates in developing (57 per 1,000 women aged 15–44 years of age) vs developed regions (42 per 1,000 women aged 15–44 years of age).1,2 Emergency contraception (EC) is an important tool in preventing unintended pregnancies and is now widely available in most countries. Early regimens, described as the Yuzpe method, consisted of taking higher doses of estrogen/progesterone combination oral contraceptives. This method was found to be less effective and the side effect profile higher than with newer methods.3 Currently there are several options, including pills: progestin-only (levonorgestrel), progesterone modulators (ulipristal acetate), antiprogesterone synthetic steroids (mifepristone), and the copper intrauterine device (IUD). In many countries, levonorgestrel has been given over-the-counter status, allowing earlier and easier access. While the mechanism of action of many of these methods is not completely understood, most are thought to work by delaying or preventing ovulation, and thus are not considered abortifacients. Of the previously described methods, the copper IUD is the most effective. The following is a review of the various options for EC. See Table 1 for a summary.

Table 1.

Methods of emergency contraception.

| Method | Dose | Timing after intercourse | Adverse effects | Relative contra-indications | Absolute contra-indications* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper IUD | Single IUD | 0–120 hours | Pain, bleeding | Bleeding disorders, ovarian cancer, high individual likelihood of exposure to gonorrhea/chlamydia, AIDS | Current pregnancy, active pelvic infection, copper allergy, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, pelvic tuberculosis, Wilson’s disease, known or suspected pelvic malignancy, uterine abnormalities that distort the uterine cavity | |

| Levonorgestrel | 1.5 mg or 0.75 mg × 2 (equal efficacy) | 0–72 hours (may be used up to 120 hrs with decreased efficacy, and off-label) | Nausea, vomiting, headache, menstrual changes | None | None | Efficacy decreased in morbidly obese Efficacy decreases with time |

| Ulipristal acetate | 30 mg | 0–120 hours | Nausea, vomiting, headache, menstrual changes | Renal/hepatic impairment, uncontrolled asthma, breast feeding (can pump and discard milk for 36 hours) | Sensitivity to Lactose monohydrate (including galactose intolerance) | Efficacy decreased in morbidly obese Limited safety data in < age 18 No change in efficacy with time (up to 120 hours) |

| Mifepristone | 10–50 mg | 0–120 hours | Nausea, vomiting, headache, menstrual changes | Adrenal failure, steroid therapy, bleeding disorders, porphyria | None | Availability limited to Armenia, China, Russia, and Vietnam |

| Yuzpe method | Combination estrogen/progesterone pilldose depends on pill brand used | 0–72 hours | Nausea, vomiting, headache, menstrual changes | None | None | Higher side effect profile |

Notes:

An established pregnancy is a contraindication to all of the above. While LNG and UPA are not abortifacients, an established pregnancy is a contraindication as they will not be efficacious. For the copper IUD, pregnancy is a contraindication as there is an increased risk of septic abortion and serious pelvic infection. For ulipristal acetate, it is contraindicated in pregnancy as animal studies showed increase pregnancy loss.51 Low doses of mifepristone are used for EC. High doses of mifepristone (200 to 600 mg) are used as an abortifacient either alone or with misoprostol, a prostaglandin analogue.

Mechanism of action

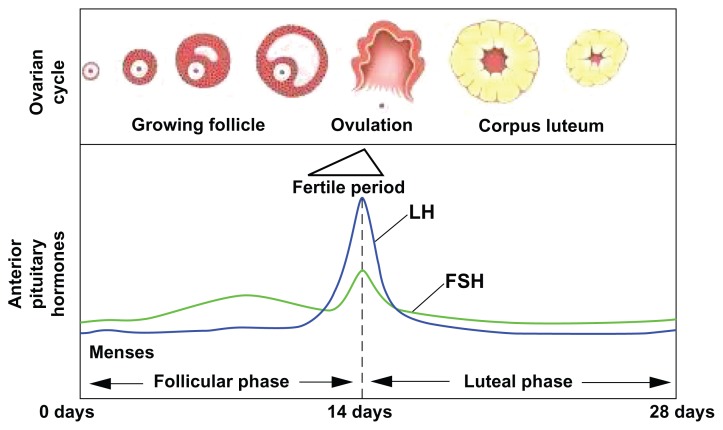

The mechanism of action of EC methods is incompletely understood. Although the time of ovulation may be difficult to predict, the fertile window extends from 5 days before ovulation (the lifespan of a sperm within the female genitourinary (GU) tract) to the day of ovulation (after which time the ovum deteriorates)4 (Fig. 1). The highest rates of conception begin 2 days before and continue up to the day of ovulation.4 Most methods are thought to prevent pregnancy by delaying or inhibiting ovulation.5,6 Other proposed mechanisms include alterations in hormone levels, changes in the endometrial environment, and inhibition of fertilization.7–9

Figure 1.

Diagram of hormonal fluctations in the menstrual cycle.

Notes: Day 0 of the menstrual cycle is the first day of menstruation. During the follicular phase LH and FSH (both released by the anterior pituitary) levels begin to rise, and peak at approximately day 14, as an egg is released from the lead follicle (top picture). The ‘fertile period’ begins approximately 5 days before the LH surge, and ends the day after, as the egg rapidly degenerates if not fertilized. LNG and the Yuzpe regimen are effective only if given before the LH surge. UPA continues to be effective until the LH surge peaks. The copper IUD continues to be effective throughout the cycle. Menstrual cycle times can vary widely by individual, thus making exact timing of the fertile period difficult to calculate.

The copper IUD is the most effective form of post-coital emergency contraception, and can be used up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse without change in efficacy. Unlike the pills described below, the mechanism of the copper IUD is somewhat different. Pre-fertilization effects are prominent.10 The copper composition can be toxic to both the ovum and the sperm.10,11 Additionally, the foreign body induces a chronic inflammatory response, leading to release of cytokines and integrins.12 These inflammatory markers cause both a spermicidal effect and inhibit implantation even if fertilization does occur.10 The copper IUD may also be effective after fertilization occurs; although the mechanism is not completely understood, these post-fertilization effects usually take place before the embryo even enters the uterus.10 The copper IUD has an additional benefit, in that it can be employed for up to 12 years and used as a form of long-acting reversible contraception preventing future unintended pregnancies.13

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is a progestin-only pill licensed in many countries around the world. As with the other forms of emergency contraception, the exact mechanism is not fully understood. Studies indicate that LNG suppresses ovulation by delaying the leutinizing hormone (LH) surge (Fig. 1).14–17 In order to be effective, it must be administered before the LH surge begins. It is thus reasonable to infer that LNG is less effective when given closer to the time of ovulation.14 However, one study found that LNG increases the amount of glycodelin in the body, which can theoretically prohibit fertilization after ovulation has occurred.18 Still, studies indicate that after ovulation occurs, LNG has only minor effects on corpus luteum function, and is thought to be ineffective once fertilization has transpired.6 Studies in rats and monkeys have demonstrated no post-fertilization effects of LNG, and most experts agree that the majority of levonorgestrel’s effects derive from inhibition of ovulation.19,20

Ulipristal acetate (UPA), a progesterone receptor modulator, was granted market authorization by the European Medicines Agency in 2009, and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010. UPA has a mechanism similar to that of LNG. Specifically, UPA delays follicular rupture by approximately 5 days, thus inhibiting or delaying ovulation.21 When ovulation is delayed by 5 days, the lifespan of sperm within the female GU tract, the chances of fertilization are greatly decreased. As with LNG, it should be administered before ovulation occurs in order to be effective. However, unlike LNG, UPA may be effective after the LH levels have already begun to rise.21 UPA generally works best when given before the LH surge, but it continues to be effective until LH levels peak. In addition to delaying or inhibiting ovulation, UPA also causes hormonal changes—specifically, a drop in LH levels and a resultant increase in menstrual cycle length.21 Some studies have shown endometrial changes after UPA administration, but the significance of these remains unclear.22,23

Mifepristone, an anti-progestin synthetic steroid, is best known as an abortifacient in large doses (200 to 600 mg) in early pregnancy. It has also been studied, mostly in China, as an emergency contraceptive option within 120 hours of unprotected sexual activity at much lower doses (10 to 50 mg).24–26 The mechanism of mifepristone as an emergency contraceptive usually occurs pre-implantation and thus is not considered an abortifacient in this context. As with other emergency contraceptive options, the effect of mifepristone varies based on the timing of administration within the menstrual cycle.6 During the follicular phase, mifepristone delays the estrogen rise, LH surge, and ovulation. In addition, it suppresses endometrial development and follicle development. These effects of mifepristone ultimately lead to inhibition of ovulation.6,27 After ovulation, mifepristone inhibits endometrial development and blocks the expression of necessary endometrial receptors. The endometrium remains immature, thus preventing implantation from effectively occurring.6,27 Mifepristone is the only pill that, at higher doses (200 to 600 mg), is effective once implantation occurs and can stop an early pregnancy from continuing, thus considered an abortifacient in this context.28,29 Mifepristone licensure and use as an emergency contraceptive is currently limited to Armenia, China, Russia, and Vietnam.30,31

The Yuzpe method is the oldest form of post-coital emergency contraception, and was first described in 1974. This method utilizes a combination estrogen and progestin.32 In the 1970s, unlicensed use of a combination of oral contraceptive pills added to the accessibility of this regimen. When utilized during the first half of the menstrual cycle, the Yuzpe method delays or inhibits ovulation. The Yuzpe method is only effective if follicles are not already well developed.8 Some studies suggest that there may be secondary mechanisms of action, including disruption of luteal function, alteration of the endometrial environment, depression of sex steroid levels, alterations in cervical mucus physiology, and inhibition of fertilization.8,9

Efficacy

There is strong evidence that all forms of emergency contraception are effective at the individual level. The copper IUD is the most effective of all forms of emergency contraception. A systemic review article by Cleland, et al33 of 42 studies analyzed patients that had copper IUDs inserted 2–10 days after unprotected intercourse. From a total of 7,034 patients around the world who had post-coital IUD insertions, there were only 10 pregnancies, with a failure rate of only 0.14% (95% CI = 0.08%–0.25%).33 There is some evidence that copper IUDs are more effective if they contain at least 380 mm2 of copper.34,35 The copper IUD is the only form of emergency contraception that continues to provide ongoing contraception for years when left in place.13 While the copper IUD is the most effective form of EC and is often offered in family planning and women’s clinics, it requires expertise and equipment necessary for insertion. This expertise is not available immediately at many sites.

The most common EC pill offered is LNG. A double-blind controlled trial involving 1998 women compared LNG with the Yuzpe method. This trial found that the crude pregnancy rate was 1.1% in the LNG group and 3.2% in the Yuzpe method group, yielding a relative risk of 0.36 (95% CI = 0.18–0.70). The estimated efficacy, when used within 72 hours of intercourse was 85% for LNG, compared with 57% in the Yuzpe method group. The efficacy (based on estimates of conception probabilities) of LNG decreased with time: from 95% at 24 hours to 58% when taken between 49–72 hours.3 Earlier administration of LNG is imperative; the recommended regimen involves administration of LNG within the first 72 hours. While LNG can be used up to 120 hours after unprotected sex, a downward gradient in efficacy has been observed during the 49–72 hour time period. The odds ratio of pregnancy, if given five days after unprotected intercourse (compared to one day), is almost 6.3,36,37 Additionally, LNG is ineffective once fertilization has occurred. LNG can be administered as a single dose regimen (1.5 mg), or less commonly as a two-dose regimen (0.75 mg q 12 hours) with no significant difference in pregnancy rate between these two regimens.25 It is important to note that the efficacy of LNG decreases as body mass index increases, with a four-fold risk of pregnancy in obese women compared to women with a normal body mass index.38

UPA has similar efficacy to LNG. Two randomized, non-inferiority, clinical trials compared the efficacy of UPA and LNG. One trial enrolled 1672 women, and found that pregnancy occurred in 0.9% (CI = 0.2%–1.6%) of the UPA group and 1.7% (95% CI = 0.8%–2.6%) of the LNG group. UPA averted 85% of unwanted pregnancies, indicating a similar efficacy when compared to LNG.39 A second trial involved 2221 women given emergency contraception within 5 days of unprotected intercourse. In the UPA group, there was a reported 1.8% (95% CI = 1.0%–3.0%) pregnancy rate; in the LNG group, there was a reported 2.6% (95% CI = 1.7%–3.9%) pregnancy rate.40 A meta-analysis combining the two trials was performed in order to increase the power, revealing a significantly lower pregnancy rate with UPA when compared to LNG. A subgroup analysis of the 203 women who received emergency contraception between 72 and 120 hours after unprotected intercourse, revealed that all 3 pregnancies in this subgroup had received LNG.40 This difference in efficacy between 72 and 120 hours is attributed to the fact that UPA is able to delay ovulation in the immediate preovulatory period, when LNG is ineffective.41 As with LNG, there was a trend toward decreased effectiveness of UPA in obese women; however, the current data is not statistically significant, with a 95% CI of 0.89–7.00.40 UPA is sold in over 60 countries.42

Mifepristone, less commonly used for emergency contraception, has been compared to both the Yuzpe method and LNG. Two randomized controlled studies studied the difference between 600 mg of mifepristone and the Yuzpe method. In both of these studies, none of the women who received mifepristone became pregnant.43,44 One study compared low dose mifepristone (10 mg) to 1.5 mg LNG in a single dose, and LNG 0.75 mg in 2 doses; pregnancy rates in this study were 1.5% with mifepristone, 1.5% with single-dose LNG, and 1.8% with two-dose LNG, leading to the conclusion that there is no difference in efficacy.25 One study found no significant difference in efficacy between three different doses of mifepristone (10, 50 and 600 mg). 45 Therefore, the lowest dose is recommended. Mifepristone is currently used only in Armenia, China, Russia, and Vietnam for this indication.31

Despite being the least effective of all forms of emergency contraception, the Yuzpe method remains in use, as it is easily accessible to women who are already on select forms of oral contraception.46 A review of eight studies showed an estimated range of effectiveness between 56.4% and 89.3%. The reduced risk of pregnancy with the Yuzpe method is 74.1% (95% CI = 62.9%–79.2%).47 As with other forms of post-coital contraception, this method is most effective the sooner it is completed after unprotected intercourse.

Safety and side effects

Emergency contraceptive methods are considered safe. Most cause alterations in hormone levels and changes in menstrual bleeding patterns. Side effects are relatively mild with most agents and may include nausea, vomiting, and headache. Of all methods, the Yuzpe method has the highest incidence of side effects, namely nausea and vomiting. There are no absolute contraindications for the most commonly used forms of EC, the progestin-only pills. Absolute contraindications exist for the copper IUD and mifepristone as detailed below. Pregnancy is noted as a contraindication to progestin-only ECPs, because they are unlikely to be effective after a pregnancy has been established. Studies have shown very little risk to a pre-existing pregnancy from LNG and the Yuzpe method.48–50 There are too few pregnant patients in the UPA studies to make a determination, but animal studies cited in the product insert reported pregnancy loss; therefore, UPA is classified as Pregnancy Category X.51 The product insert instructs that if pregnancy cannot be excluded on the basis of history and/or physical exam, a pregnancy test is recommended prior to use.51

The most common side effects with the copper IUD are pain during the insertion process and increased menstrual bleeding.52 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and local anesthesia are commonly utilized if discomfort is experienced during the procedure. Absolute contraindications to copper IUD placement are the same as with routine insertion and include pregnancy (due to increased risk of septic abortion and serious pelvic infection), undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, malignant gestational trophoblastic disease, active pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic tuberculosis infection or purulent cervicitis, copper allergy, Wilson’s disease, known or suspected pelvic malignancy, and uterine abnormalities that distort the uterine cavity.53

LNG is generally well tolerated. The most common side effects with LNG are nausea (23%) and vomiting (5.6%). Less common events include fatigue, dizziness, headache, and mastalgia. Disruption in the menstrual cycle pattern may also occur.

UPA has a similar side effect profile when compared to the other hormonal emergency contraceptive pills. Headache is the most common side effect, occurring in 19% of patients.41 Other side effects include nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and lower abdominal pain.39 In addition, menstrual cycle length increased by approximately 2.8 days, with no change in duration of menstrual bleeding.54 UPA is metabolized by the kidney and the liver, therefore UPA is contraindicated in severe kidney or liver disease. UPA use in severe, uncontrolled asthma is a relative contraindication, as UPA has some antagonist effect at glucocorticoid receptors. Since ella and ella- One® one contain lactose monohydrate, they should not be offered to those with rare errors of galactose metabolism.41 If UPA is used while breast feeding, breast milk should be discarded for 36 hours, as it is a lipophilic compound, and therefore could be secreted in breast milk. Data from rat and rabbit studies show increased perinatal deaths for the offspring of those exposed to UPA. In those animals that survived, however, there were no increased fetal malformations.51 As noted previously, if pregnancy cannot be ruled out based on patient history, a pregnancy test prior to administration is recommended.51 Data is limited for pregnant women, but preliminary data from a meta-analysis and post-marketing surveillance suggests that there is little harm to the fetus.40 If a patient becomes pregnant after taking ellaOne®, the provider should enter the patient into the HRA Pharma ellaOne® pregnancy registry (http://www.hra-pregnancy-registry.com/en/, accessed 11/19/12). Patients should be counseled that oral contraceptives may be less effective throughout the current cycle, and an alternate method of birth control should be used throughout the current cycle.

Side effects of mifepristone include nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, fatigue, mastalgia, lower abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Studies indicate that a larger dose of mifepristone correlates with a longer delay to menses.45 Absolute contraindications to mifepristone use include chronic adrenal failure, steroid therapy, severe asthma, bleeding disorders, known hypersensitivity to prostaglandins or mifepristone, and porphyria.55

The Yuzpe method has more pronounced side effects than the other regimens for emergency contraception. 50% of women develop nausea, and 20% develop vomiting. Antiemetic medications are recommended if the Yuzpe method is used. Changes in menstrual bleeding and mastalgia also occur.43 Although there is a theoretical concern for increased risk of venothromboembolism with high dose estrogen therapy, current studies do not support any increased risk with brief use of estrogen.56 Prescribers should consider alternatives if patients have relative contraindications to combined estrogen/progesterone therapy.

Clinical Considerations

Recommendations as to which ECP to use depends on a number of factors, including timing of presentation after unprotected sexual intercourse, patient factors (such as obesity, allergies, and concurrent medications), cost, and availability.

Timing of unprotected sexual intercourse

While all methods are highly effective within 72 hours of unprotected sexual intercourse, UPA may be more effective in those who present 72–120 hours.40 While LNG can be administered after 72 hours and before 120 hours, it is less effective, and is not currently labeled for use as such. The copper IUD does not decrease in efficacy over the 120 hours.

Patient factors

Weight: While BMI > 30 kg/m2 is not considered a contraindication to ECPs, both LNG and UPA were found to be less effective in patients with BMI > 30. Although no studies have looked at this specifically, sub-group analysis from a meta-analysis showed a statistically significant increase in risk of failure in the LNG group: OR 4.41 in the LNG group and 2.62 in the UPA group for obese women with BMI > 30.40 UPA was more efficacious than LNG in obese women; UPA may therefore be preferred to LNG in this population, although more studies are needed. The efficacy of the copper IUD does not change with BMI, and therefore this method may be preferred in women with BMI > 35.

Uncontrolled asthma: In those patients with uncontrolled asthma on glucocorticoids, LNG is preferable to UPA, as UPA blocks glucocorticoid receptors and may theoretically worsen asthma (although there are no studies specifically looking at this).

Concomitant medications: Since UPA and LNG are metabolized by the CYP3A4 microsomal system, medications which induce the CYP3A4 system (such as barbiturates, carbamazepine, felbamate, griseofulvin, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, St. John’s Wort, and topiramate) may decrease levels of UPA, but the actual effect of these interactions is unclear.51 Some experts recommend against concomitant use of these medications and UPA.57 Where readily available, insertion of a copper IUDs may be preferable in a patient who has taken any of these medications in the past 28 days.51 Theoretically, drugs that inhibit the CYP3A4 system (such as anti-retrovirals used for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis, itraconazole, and clarithromycin) may inhibit the metabolism of UPA, and lead to increased levels of UPA. Currently there is scant literature evaluating this interaction in vivo. Medications that decrease the pH of the stomach (including antacids, H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors) may decrease the absorption and efficacy of UPA; therefore, discussion with patients regarding the potential decreased efficacy in these situations is warranted.51

Breastfeeding: Most EC is safe when breastfeeding. Mifepristone should not be used in women who are breastfeeding. UPA is a lipophilic compound, and therefore could be excreted in breast milk. If UPA is taken, most experts recommend discarding breast milk for 36 hours.

After EC is given, and when appropriate, contraception should be started to prevent further episodes of unplanned pregnancies (‘quick start’ contraception). As LNG and UPA may prevent or delay ovulation, subsequent episodes of unprotected sexual intercourse, may lead to pregnancy; therefore, it is recommended in all cases that patients use a barrier method to prevent unintended pregnancies after ECPs. Since UPA is a progesterone receptor modulator, it could theoretically interfere with OCPs that contain progesterones. When progesterone containing OCPs are started immediately, patients should also be advised to use barrier protection or abstain from sexual activity until the next menstrual cycle.51 Providers should remind patients that EC does not prevent HIV or other sexual transmitted infections and stress the importance of barrier protection. Patients who do not experience a menstrual cycle one week after her usual expected menstrual cycle or three weeks after taking ECPs should take a pregnancy test and/or seek medical care.

Place in Therapy

Increased access has led to increased use of emergency contraception methods.58 Emergency contraception is offered, provided, and/or dispensed in emergency rooms, outpatient clinics and pharmacies. EC can also be provided in advance, allowing earlier and easier access. Women can receive ECPs and copper IUDs through family planning, public health, and other outpatient clinics. Dedicated emergency contraceptive pill products are available in over 140 countries worldwide.59 In over 60 of these countries including Ireland, Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Israel, and the United Kingdom, ECPs are over-the-counter and can be obtained in pharmacies without a prescription.59 In France, ECPs are free of charge to minors and can be dispensed anonymously from pharmacies.59 Some countries have age restrictions and prescription requirements, such as the US where Plan B One-Step® (levonorgestrel) is over-the- counter for men and women 17 years of age and older, but requires a prescription for females under 17-years-old.60

In addition to outpatient clinics and pharmacies, emergency rooms play an important role in access to ECPs for women, especially those seeking medical care after a sexual assault. In many countries around the world, such as the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, governments and hospitals have created protocols and guidelines that include counseling about and provision of ECPs for sexual assault survivors.61 In the US, medical groups such as the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, as well as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommend that ECPs be offered routinely after sexual assault.62–64 Emergency departments in 17 states and the District of Columbia are required by law to provide EC related services to sexual assault victims upon request.60 International organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Health and Community Section in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the Interagency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations have produced protocols that emphasize the importance of access to and provision of ECPs to refugees following rape.61

Patient Preference

Preference for the different types of EC largely depends on patient and provider knowledge, as well as availability and access. Two large studies from China, where almost 60% of all married women use IUDs for contraception, and a small pilot study from the US showed that women who received the copper IUD for EC found it an acceptable option.65 Continuation rates ranged from 61%–94%, depending on the follow-up time and parity of participant.52,66,67 The copper IUD is the most effective form of EC, has been used as EC for over 35 years, can provide up to 12 years of reversible contraception, and does not decrease in efficacy over the duration of time when it can be used.33,52,67,68 Despite the long-term contraceptive benefits of the copper IUDs, this method remains underutilized. The necessity of IUD placement by a trained health care provider, high up-front costs, lack of provider and patient knowledge regarding the IUD’s effectiveness and use as a form of EC, all contribute to the relatively low use of the copper IUDs as a form of EC.69–71 Two studies from the US of adolescents and young women presenting to family planning clinics reported that when counseled on IUDs for EC, 13%–15% of them would choose an IUD, with increased numbers if provided on the same day and at free cost.69,72 The copper IUD is also cost effective in the long term given decreased healthcare costs due to lower unintended pregnancy rates compared to oral levonorgestrel pills.73 These studies suggest that with increased provider and patient education, lower costs, and improved access to trained providers, there may be more women who choose copper IUDs for emergency contraception.

ECPs are more widely available and are the most common type of EC used worldwide. Studies indicate, however, that they are still underutilized, and thus are not associated with a reduction in the unintended pregnancy or abortion rate at the population level.58,74 Utilization of ECPs remains low in many countries around the world. In the United States, data from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006–2008 showed that even after ECPs became available without a prescription for people 17 years of age and older, the number of women who reported using ECPs remained below 10% (9.7%).75 In other countries, Demographic and Health Survey data from 2005–2009 indicated a higher use of EC, though still under 25% of unmarried sexually active women reported use: 21.7%, 15%, 11%, and 10%, in Albania, Ukraine, Kenya, and Colombia respectively.76–78

Factors Affecting ECP Use: Knowledge, Prescriptive Practices, and Access

Successful use of emergency contraception requires accurate knowledge about the different EC methods by both providers and patients, prescriptions when necessary for obtaining ECPs, and access to the different methods. Studies from over a decade ago show poor knowledge about EC among healthcare providers (HCP) and patients as well as a lack of counseling about and dispensing of ECPs by HCPs. For example, a study published in 2000 reported only 20% of pediatricians ever prescribing ECPs while another study in 2001 revealed that only 17% of pediatricians routinely counseled adolescents about the availability of EC.79,80 Two studies in 1998 of adolescents in the US, revealed that only one third (28% in one study and 30% in the other) of the respondents had heard of EC.81,82 More recent studies have shown some improvement in the number of patients who have heard of EC, though less so among populations at higher risk of unplanned pregnancies such as adolescents. A literature review published in 2012 on male knowledge about ECPs in the US showed that 38% of adolescent males and 65%–100% of adult males were familiar with EC.83 48% of pregnant teens presenting for an abortion to clinics in Shanghai had heard about EC.84 Slightly higher rates were found at a teen clinic in Hawaii (56%)85 and among sexually active teens in Switzerland (89% of girls and 75% of boys).86 In sub-Saharan Africa, knowledge about EC ranged from 57% of rural women in Ghana to between 47% and 84% of female students at 2 different universities in Ethiopia.87–89

Unfortunately, despite awareness of the availability of emergency contraception, knowledge about timing, and appropriateness continues to be an issue. A study from 2004 reported that 77% of women presenting to an inner-city emergency department in the US having heard of EC, although 25%–50% of them did not have sufficient knowledge to use it effectively.90 Similarly, two studies from 2009 showed an increase in the number of providers aware of the method, but there remained a lack of accurate medical knowledge about the method.91,92 71% of family medicine providers in Pakistan had heard of EC.91 Despite the widespread knowledge of the product, only 40% had prescribed it, 24% felt it was an abortifacient, and 42% were unsure if it was an abortifacient.91 85% of pediatric emergency medicine physicians in the US reported prescribing ECPs to adolescents but 43% of respondents answered > 50% of knowledge based questions about EC incorrectly.92 Nearly all of the 448 Jamaican and Barbadian health care providers surveyed had heard of EC, but only one in five knew it could be prescribed as often as needed.93

There also continues to be a bias towards restricting EC access to adolescents despite its proven efficacy and safety as well as recommendations for improved access for high-risk populations such as adolescents.62,94 A study of Nicaraguan pharmacists showed that the majority of them sold EC at least once a week (92%) and 65% of them were willing to provide them to all women in need, but only 13% would dispense to minors.95 A qualitative study of physicians and nurses working in three large academic, urban, free-standing pediatric emergency rooms in the US found that nurses commonly expressed views that adolescents who may need EC are irresponsible and that EC should only be used after an assault and very few nurses, physicians, or NPs supported advance prescription for EC.96

“Advance provision” of emergency contraception refers to providing patients with ECPs or a prescription for ECPs for patients to fill as needed in the future. Advanced provision has been shown to increase the use of ECPs in multiple studies.58,74,97–101 Concerns that advanced provision will increase rates of sexually transmitted infections and unprotected sexual activity have proven to be unfounded.98,102–104 However, although EC is effective in reducing unplanned pregnancy on an individual level, studies including a Cochrane metaanalysis indicate that emergency contraception pills, even with advanced provision, are not associated with a reduction in the unintended pregnancy, or abortion rates at a population level.58,74,105 Reported reasons for underuse of emergency contraception methods at an individual level include failure to recognize the risk of conception, misunderstanding about the appropriate time frame to use emergency contraception, lack of knowledge on where to obtain the medication, and perceived risk or stigma.58,106 Although EC has not affected pregnancy and abortion rates at a population level, medical, policy and public health groups continue to recommend advanced provision for vulnerable populations such as adolescents.62,107

Access to emergency contraception has also been influenced by politics, which has been tied to gender issues and individuals’ and groups’ beliefs about abortion and contraception. These factors determine whether providers and hospitals offer ECPs, as well as if ECPs are provided by pharmacies over-the-counter with or without pharmacist intervention, by prescription only, or sold freely. Access can also depend on whether the government believes EC to be a form of contraception or a form of abortion. For example in Peru, the Ministry of Health (MINSA) issued a resolution (No. 167-2010) categorizing EC as a contraceptive method allowing Peruvian public health facilities to distribute ECPs to women for free.108 Soon after, a petition was filed and MINSA issued a subsequent resolution (No. 652-2010) that prohibits free distribution of EC, making EC essentially inaccessible.109

In 1998, Mexico first began considering the inclusion of emergency contraception as part of their public health services but it did not officially become part of the Health Sector List of Essential Medications until 2005.110 At that time, the Catholic Church threatened to excommunicate women who used EC as well as those who provided it.110 Chile first introduced ECPs in 2001 by prescription but lawsuits were quickly filed by groups opposing EC.111 Due to legal issues, political pressure and opposition from religious groups, it was not until 2010 that ECPs were made affordable and available in pharmacies and public health clinics for all women 14 years of age and older.59,111 The US FDA delayed approving behind the counter status for EC (for those over age 17) for three years despite evidence of efficacy and safety. EC remains prescription only for those under age 17, despite recommendations to eliminate age restrictions from FDA experts.112

Conclusion

In 2008, there were approximately 208 million pregnancies worldwide, of which approximately 41% were unintended.1 As availability of EC can decrease the number of unintended pregnancies, many medical groups, nonprofit organizations and experts in a variety of fields, including but not limited to the American Academy of Pediatrics, The United Nations Population Fund, The World Health Organization, and The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, advocate for easy access to emergency contraceptive pills.59 ECPs are safe and there are no absolute contraindications for usage of LNG or the Yuzpe method and few relative contraindications to UPA, low dose mifepristone, and the copper IUD. The copper IUD, LNG, UPA, and low dose mifepristone are highly effective in preventing unintended pregnancies when used as directed. Providers working with women in clinics, emergency departments, and pharmacies should be familiar with the availability of medications, as well as options for provision. Patient preference, provider capability, and local availability will influence which options are most preferable.

Abbreviations

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- IUD

Intrauterine device

- LNG

Levonorgestrel

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- ECPs

Emergency contraceptive pills

- EC

Emergency contraception

- HCP

Healthcare provider

- UPA

Ulipristal acetate

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AK, LH, JL all contributed to the first draft, as well as all subsequent revisions, of the manuscript. AK, LH, JL jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. AK, LH, JL reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures and Ethics

As a requirement of publication author(s) have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. Any disclosures are made in this section. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest. Provenance: the authors were invited to submit this paper.

Funding

No outside funding was provided in the writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: Worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an unmet need for contraception in developing countries and their reasons for not using a method. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec;333(23):1517–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gemzell-Danielsson K, Berger C, Lalitkumar P. Emergency contraception— mechanisms of action. Contraception. 2012:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marions L, Hultenby K, Lindell I, Sun X, Stabi B, Danielsson KG. Emergency contraception with mifepristone and levonorgestrel: Mechanism of action. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swahn ML, Westlund P, Johannisson E, Bygdeman M. Effect of post-coital contraceptive methods on the endometrium and the menstrual cycle. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996 Sep;75(8):738–44. doi: 10.3109/00016349609065738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croxatto HB, Fuentealba B, Brache V, et al. Effects of the Yuzpe regimen, given during the follicular phase, on ovarian function. Contraception. 2002;65(2):121–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ling WY, Robichaud A, Zayid I, Wrixon W, MacLeod SC. Mode of action of DL-norgestrel and ethinylestradiol combination in postcoital contraception. Fertil Steril. 1979;32(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)44237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanford JB, Mikolajczyk RT. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices: Update and estimation of postfertilization effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(6):1699–708. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.128091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ammala M, Nyman T, Strengell L, Rutanen E. Effect of intrauterine contraceptive devices on cytokine messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the human endometrium. Fertil Steril. 1995;63(4):773–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savaris R, Zettler CG, Ferrari AN. Expression of α4β1 and αvβ3 integrins in the endometrium of women using the T200 copper intrauterine device. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(6):1102–7. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivin I. Utility and drawbacks of continuous use of a copper T IUD for 20 years. Contraception. 2007;75(Suppl 6):S70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand M, del Carmen Cravioto M, Raymond EG, et al. On the mechanisms of action of short-term levonorgestrel administration in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;64(4):227–34. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hapangama D, Glasier AF, Baird DT. The effects of peri-ovulatory administration of levonorgestrel on the menstrual cycle. Contraception. 2001;63(3):123–9. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croxatto HB, Brache V, Pavez M, et al. Pituitary–ovarian function following the standard levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive dose or a single 0.75-mg dose given on the days preceding ovulation. Contraception. 2004;70(6):442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durand M, del Carmen Cravioto M, Raymond EG, et al. On the mechanisms of action of short-term levonorgestrel administration in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2001;64(4):227–34. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand M, Koistinen R, Chirinos M, et al. Hormonal evaluation and mid-cycle detection of intrauterine glycodelin in women treated with levonorgestrel as in emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):526–33. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller AL, Llados CM, Croxatto HB. Postcoital treatment with levonorgestrel does not disrupt postfertilization events in the rat. Contraception. 2003;67(5):415–9. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortiz ME, Ortiz RE, Fuentes MA, Parraguez VH, Croxatto HB. Post-coital administration of levonorgestrel does not interfere with post-fertilization events in the new-world monkey Cebus apella. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(6):1352–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brache V, Cochon L, Jesam C, et al. Immediate pre-ovulatory administration of 30 mg ulipristal acetate significantly delays follicular rupture. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(9):2256–63. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stratton P, Levens ED, Hartog B, et al. Endometrial effects of a single early luteal dose of the selective progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):2035–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passaro MD, Piquion J, Mullen N, et al. Luteal phase dose-response relationships of the antiprogestin CDB-2914 in normally cycling women. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(9):1820–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng L, Che Y, Gülmezoglu AM. Interventions for emergency contraception. Chochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001324.pub4. Art.No.:CD001324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Peregoudov A, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comparison of three single doses of mifepristone as emergency contraception: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9154):697–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bygdeman M, Danielsson KG, Marions L, Swahn ML. Contraceptive use of antiprogestin. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 1999;4(2):103–7. doi: 10.3109/13625189909064011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvestre L, Dubois C, Renault M, Rezvani Y, Baulieu E-E, Ulmann A. Voluntary interruption of pregnancy with mifepristone (RU 486) and a prostaglandin analogue. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(10):645–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003083221001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodger M, Baird D. Induction of therapeutic abortion in early pregnancy with mifepristone in combination with prostaglandin pessary. Lancet. 1987;2(8573):1415–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westley E, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception: global challenges, new opportunities. Contraception. 2012;85(5):429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trussell J, Raymond EG. Emergency contraception: a last chance to prevent unintended pregnancy. 2012. [Accessed Oct 20, 2012]. pp. 1–31. Available at: http://ec.princeton.edu/questions/ec-review.pdf.

- 32.Yuzpe AA, Thurlow HJ, Ramzy I, Leyshon JI. Post coital contraception – A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: A systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(7):1994–2000. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Brien PA, Kulier R, Helmerhorst FM, Usher-Patel M, d’Arcangues C. Copper-containing, framed intrauterine devices for contraception: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception. 2008;77(5):318–27. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56(6):341–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piaggio G, Kapp N, von Hertzen H. Effect on pregnancy rates of the delay in the administration of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a combined analysis of four WHO trials. Contraception. 2011;84(1):35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noé G, Croxatto HB, Salvatierra AM, et al. Contraceptive efficacy of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel given before or after ovulation. Contraception. 2010;81(5):414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creinin M, Schlaff W, Archer DF, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089–97. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000239440.02284.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron ST. Emergency contraception options: Focus on ulipristal acetate. Clin Med Insights: Women’s Health. 2012;4:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dedicated emergency contraceptive pills worldwide. 2012. [Accessed Nov 11, 2012]. http://ec.princeton.edu/pills/Dedicated_ECPs.pdf.

- 43.Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Mifepristone (RU 486) compared with high-dose estrogen and progestogen for emergency postcoital contraception. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(15):1041–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210083271501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb AM, Russell J, Elstein M. Comparison of Yuzpe regimen, danazol, and mifepristone (RU486) in oral postcoital contraception. BMJ. 1992;305(6859):927–31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6859.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin J, Weisberg E, Fraser IS. Comparison of three single doses of mifepristone as emergency contraception: A randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45(6):489–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wertheimer RE. Emergency postcoital contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(10):2287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trussell J, Rodríguez G, Ellertson C. Updated estimates of the effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Contraception. 1999;59(3):147–51. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Chen J, Wang Y, Ren F, Yu W, Cheng L. Pregnancy outcome after levonorgestrel-only emergency contraception failure: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(7):1605–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raman-Wilms L, Tseng A, Wighardt S, Einarson T, Koren G. Fetal genital effects of first-trimester sex hormone exposure: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(1):141–9. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00341-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bracken M. Oral contraception and congenital malformations in offspring: a review and metaanalysis of the prospective studies. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76(3):552–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulipristal acetate. [Prescribing Information] 2010. [Accessed Nov 20, 2012]. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022474s000Lbl.pdf.

- 52.Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: A prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fine PM, Mathe H, Ginde S, Cullins V, Morfesis J, Gainer E. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2):257–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c8e2aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mifeprex Medication Guide. Mifeprex. 2006. files/84/Interstitial.html.

- 56.Vasilakis C, Jick SS, Jick H. The risk of venous thromboembolism in users of postcoital contraceptive pills. Contraception. 1999;59(2):79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gemzell-Danielsson K, Meng C-X. Emergency contraception: potential role of ulipristal acetate. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2010 Apr;2:53–61. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(1):181–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250904.06923.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.International Consortium for Emergency Contraception: EC Status and Availability Database. [Accessed Oct 1, 2012]. http://www.cecinfo.org/index.php.

- 60.States Policies in Brief: Emergency Contraception. Washington, DC: Guttmacher Institute; Oct 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Governments worldwide put emergency contraception into women’s hands: A global review of laws and policies. 2004. pp. 1–19. [Briefing paper] Available at: http://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/documents/pub_bp_govtswwec.pdf.

- 62.Access to emergency contraception. Committee opinion No. 542. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(542):1250–3. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318277c960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sexual assault and STDs. STD Treatment Guidelines 2010. [Accessed Oct 10, 2012]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/sexual-assault.htm.

- 64.Policy of the House of Delegates. American Medical Association; 2004. H-75, 985 Access to Emergency Contraception. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salem R. New Attention to the Iud: Expanding Women’s Contraceptive Options to Meet Their Needs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: The INFO Project; Feb, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Simonsen SE, Gurtcheff SE, Trauscht-Van Horn J, Murphy PA. The copper T380A IUD vs. oral levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a prospective observational study. Contraception. 2011;84(3):321–2. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou L, Xiao B. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: a multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107–12. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The Intrauterine Device (IUD) for Emergency Contraception. New York, NY: International Consortium for Emergency Contraception; Sep, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turok DK, Gurtcheff SE, Handley E, et al. A survey of women obtaining emergency contraception: are they interested in using the copper IUD? Contraception. 2011;83(5):441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harper C, Speidel JJ, Drey EA, Trussell J, Blum M, Darney P. Copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception: Clinical practice among contraceptive providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(2):220–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182429e0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wright RL, Frost CJ, Turok DK. A qualitative exploration of emergency contraception users’ willingness to select the copper IUD. Contraception. 2012;85(1):32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh ML, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819c856c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dermish A, Turok D, Kim J. Cost-effectiveness of emergency contraception— IUDS versus oral EC. Contraception. 2012;86(3):316. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu X, Cheng L, Hua X, Glasier A. Advanced provision of emergency contraception to postnatal women in China makes no difference in abortion rates: a randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2005;72(2):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kavanaugh ML, Williams SL, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knowledge and ever used of emergency contraception in Africa. [Accessed Oct 5, 2012]. http://www.cecinfo.org/UserFiles/File/DHS/Emergency%20Contraception%20in%20Africa.pdf.

- 77.Knowledge and ever used of emergency contraception in Latin America. [Accessed Oct 5, 2012]. http://www.cecinfo.org/UserFiles/File/DHS/Emergency%20Contraception%20in%20Latin%20America.pdf.

- 78.Knowledge and ever used of emergency contraception in Europe and West Asia. [Accessed Oct 5, 2012]. http://www.cecinfo.org/UserFiles/File/DHS/Emergency%20Contraception%20in%20Europe%20and%20West%20Asia.pdf.

- 79.Golden NH, Seigel WM, Fisher M, et al. Emergency contraception: Pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes, and opinions. Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):287–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sills MR, Chamberlain JM, Teach SJ. The Associations Among Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Emergency Contraception. Pediatrics. 2000;105(Suppl 3):954–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohall A, Dickerson D, Vaughan R, Cohall R. Inner-city adolescents’ awareness of emergency contraception. JAMWA. 1998;53(5):258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delbanco S, Parker M, McIntosh M, Kannel S, Hoff T, Stewart F. Missed opportunities: Teenagers and emergency contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(8):727–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.8.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marcell AV, Waks AB, Rutkow L, McKenna R, Rompalo A, Hogan MT. What do we know about males and emergency contraception? A synthesis of the literature. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(3):184–93. doi: 10.1363/4418412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu J, Cheng L. Awareness and usage of emergency contraception among teenagers seeking abortion: A Shanghai survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;141(2):143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ahern R, Frattarelli LA, Delto J, Kaneshiro B. Knowledge and awareness of emergency contraception in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(5):273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ottesen S, Narring F, Renteria S-C, Michaud P-A. Emergency contraception among teenagers in Switzerland: a cross-sectional survey on the sexuality of 16- to 20-year-olds. J Adol Health. 2002;31(1):101–10. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ahmed FA, Moussa K, Petterson K, Asamoah B. Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practice of emergency contraception: a cross-sectional study among Ethiopian undergraduate female students. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Opoku B, Kwaununu F. Knowledge and practices of emergency contraception among Ghaniaian women. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(2):147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tilahyn D, Assefa T, Belachew T. Knowledge, attitude and practice of emergency contraceptives among Adama University female students. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20(3):195–202. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v20i3.69449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abbott J, Feldhaus KM, Houry D, Lowenstein SR. Emergency contraception: What do our patients know? Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(3):376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abdulghani H, Karim S, Irfan F. Emergency contraception: knowledge and attitudes of family physicians of a teaching hospital, Karachi, Pakistan. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(3):339–44. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i3.3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goyal M, Zhao H, Mollen C. Exploring emergency contraception knowledge, prescription practices, and barriers to prescription for adolescents in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):765–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yam E, Gordon-Strachan G, McIntyre G, et al. Jamaican and Barbadian health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding emergency contraceptive pills. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2007;33(4):160–7. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.33.160.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Improving Access to Emergency Contraception. New York, NY: International Consortium for Emergency Contraception; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ehrle N, Sarker M. Emergency contraceptive pills: Knowledge and attitudes of pharmacy personnel in Managua, Nicaragua. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2011;37(2):67–74. doi: 10.1363/3706711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miller MK, Plantz DM, Denise Dowd M, et al. Pediatric emergency health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding emergency contraception. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(6):605–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jackson R, Schwarz E, Freedman L, Darney P. Advance supply of emergency contraception: Effect on use and usual contraception—A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raine T, Harper CC, Rocca C, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and stis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(1):54–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lo SST, Fan SYS, Ho PC, Glasier AF. Effect of advanced provision of emergency contraception on women’s contraceptive behaviour: A randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(10):2404–10. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ekstrand M, Larsson M, Darj E, Tydén T. Advance provision of emergency contraceptive pills reduces treatment delay: A randomised controlled trial among Swedish teenage girls. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(3):354–9. doi: 10.1080/00016340801936024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Harper C, Cheong M, Rocca C, Darney P, Raine T. The effect of increased access to emergency contraception among young adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):483–91. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000174000.37962.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Belzer M, Sanchez K, Olson J, Jacobs AM, Tucker D. Advance supply of emergency contraception: A randomized trial in adolescent mothers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18(5):347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gold M, Wolford J, Smith K, Parker A. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ellertson C, Ambardekar S, Hedley A, Coyaji K, Trussell J, Blanchard K. Emergency contraception: Randomized comparison of advance provision and information only. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(4):570–5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Polis C, Grimes DA, Schaffer K, Blanchard K, Glasier A, Harper C. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005497.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Free C, Lee RM, Ogden J. Young women’s accounts of factors influencing their use and non-use of emergency contraception: in-depth interview study. BMJ. 2002;325:1393–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7377.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Policy Statement: Emergency contraception: Committee on Adolescence. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1174–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mitchell C. Peru reinstates free distribution of emergency contraception after WHO asserts that EC does not cause abortion. 2010. [Accessed Oct 10, 2012]. http://blog.iwhc.org/2010/04/peru-reinstates-free-distribution-of-emergency-contraception-after-who-asserts-that-ec-does-not-cause-abortion/

- 109.Indice CLAE de acceso a la anticoncepcion de emergencia: La situacion de la anticoncepcion de emergencia en America Latina y El Caribe: Barreras y facilitadores en la accesibilidad: Consorcio Latinoamericano de Anticoncepcion de Emergencia; Oct 2010.

- 110.Amuchastegui A, Cruz G, Aldaz E, Mejia MC. Politics, religion and gender equality in contemporary Mexico: women’s sexuality and reproductive rights in a contested secular state. Third World Q. 2010;31(6):989–1005. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2010.502733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Guzman V, Seibert U, Staab S. Democracy in the country but not in the home? Religion, politics and women’s rights in Chile. Third World Q. 2010;31(6):971–88. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2010.502730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wood AJJ, Drazen JM, Greene MF. The Politics of Emergency Contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):101–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1114439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]