Abstract

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer in women and the third most common in men worldwide. In this study, we used MEDLINE to conduct a systematic review of existing literature published in English between 2000 and 2010 on patterns of colorectal cancer care. Specifically, this review examined 66 studies conducted in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand to assess patterns of initial care, post-diagnostic surveillance, and end-of-life care for colorectal cancer. The majority of studies in this review reported rates of initial care, and limited research examined either post-diagnostic surveillance or end-of-life care for colorectal cancer. Older colorectal cancer patients and individuals with comorbidities generally received less surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. Patients with lower socioeconomic status were less likely to receive treatment, and variations in patterns of care were observed by patient demographic and clinical characteristics, geographical location, and hospital setting. However, there was wide variability in data collection and measures, health-care systems, patient populations, and population representativeness, making direct comparisons challenging. Future research and policy efforts should emphasize increased comparability of data systems, promote data standardization, and encourage collaboration between and within European cancer registries and administrative databases.

In 2008, an estimated 2.1 million individuals were diagnosed with colorectal cancer worldwide, with nearly 60% residing in developed regions (1,2). Globally, colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer in women and third in men (1,2). Although rates vary significantly by regions of the world, Australia/New Zealand and Western Europe have among the highest estimated incidence rates of colorectal cancer (1,2). For both genders, Central and Eastern Europe have the highest mortality rates because of colorectal cancer worldwide (1,2). Given that the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer increases with older age, global prevalence is rising over time because of growing proportions of elderly (1,2). Better methods of screening and early detection and advances in treatment are also improving survival, further contributing to increasing prevalence (1,2). Undoubtedly, these increases have significant implications for health-care costs, delivery, and service utilization associated with this disease.

Given high rates of mortality and incidence for colorectal cancer in certain parts of Europe, this region of the world is an important area of international focus. Available comparative research on cancer in European countries has primarily come from studies conducted by EUROCARE, a research collaboration between several European population-based cancer registries that began in 1990 (3). EUROCARE was designed to develop standardized measures for improved comparability of cancer data between European countries and explore trends in patterns of cancer treatment and survival (3). Findings from these studies have demonstrated considerable variation in age-adjusted 5-year survival by country and region, with the highest colorectal cancer survival rates in northern European countries and the lowest in Eastern European countries (4–9).

A study comparing colorectal cancer survival in Europe to the United States during the period of 1985–1989 found that 5-year survival ranged from 13% to 22% higher in the United States depending upon tumor subsite (10). Verdecchia et al. compared data from 47 European registries to data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and noted higher mean survival in the United States compared with Europe for multiple cancers, including colorectal cancer, for patients diagnosed in 1995–1999 and followed up to December 2003 (7). Although limited, existing studies have suggested that differences in stage at diagnosis, postoperative mortality, and access to care may be factors that partially explain variations in outcomes between European nations (11–13).

With the larger goal of improving delivery of population-based care for colorectal cancer, assessment of current practices is a necessary first step. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review of published studies to evaluate patterns of initial care following diagnosis, post-diagnostic surveillance, and end-of-life care for colorectal cancer in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Examination of this literature will provide a deeper understanding of care patterns and trends over time and may identify disparities in treatment. Assessment of data comparability between nations can also inform data collection and in combination with patient outcomes and cost data, assist resource allocation, health-care delivery, and research and policy efforts targeting colorectal cancer treatment.

Methods

Study Selection and Criteria

The MEDLINE database was used to identify articles on colorectal cancer care published in English between January 2000 and December 2010. The Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term “Colorectal Neoplasms” was combined with additional headings or text strings related to patterns of care, such as “physician’s practice patterns,” “guideline adherence,” “chemotherapy,” and “radiotherapy” (see Appendix). In total, this search strategy yielded 717 articles.

Articles were hierarchically excluded according to the following criteria: 1) article was an editorial, letter, essay, commentary, conference paper, note, published guideline, highlight, or review; 2) study was based on biological specimens, nonhuman population, simulation model, or hypothetical cohort; 3) study did not report receipt of initial, post-diagnostic surveillance, or end-of-life colorectal cancer care; 4) study reported results from a clinical study or controlled trial evaluating a specific treatment; 5) study included only outcome measures, such as survival; 6) study had sample size of less than 200 cancer patients; and 7) study did not report data for colorectal cancer care separately from other cancer sites.

Data Abstraction

After applying the exclusion criteria to the 717 identified articles, a total of 105 studies were retained and abstracted by four individuals. Additionally, because electronic searches may not include all relevant studies, we reviewed the reference lists of these 105 articles and published reviews of colorectal cancer treatment (14–25) to identify additional studies for possible inclusion. Through this process, the study team identified 34 additional articles that were also included and abstracted. In total 139 studies were abstracted and a subset of 66 articles reporting patterns of colorectal cancer care in countries outside of North America were included in this systematic review (25–90).

The countries represented in this review include Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Additionally, one study included in the review compared data from cancer registries in multiple European countries: Genoa and Varese, Italy; Côte-d’Or, France; Granada, Navarra, and Tarragona, Spain; Tampere, Finland; Estonia; Slovenia; Slovakia; and Krakow and Kielce, Poland. The remaining 73 articles were included in the companion review conducted by Butler et al., which examines patterns of colorectal cancer care in the United States and Canada (91).

A standardized abstraction form was used to record information on study characteristics and principal findings, including initial care and treatment (eg, surgery, radiotherapy [RT], chemotherapy), post-diagnostic surveillance, and end-of-life care. We also abstracted several study characteristics, including reporting of stage, year of diagnosis or treatment, sample size, patient age, health delivery setting, and data sources. In order to ensure comparability between reviewers, three quality control reviews were conducted and compared for uniformity in abstraction procedures. After each quality control review, adjustments were made to increase consistency in data abstraction. By the last quality review, it was determined that comparability among the four reviewers had been achieved, and studies that were abstracted prior to this point were revisited for secondary abstraction.

Data Analyses

Data are presented for initial care following colorectal cancer diagnosis, post-diagnostic surveillance, and end-of-life care. We abstracted “chemoradiation” or “any adjuvant therapy” as reported in the underlying studies and classified treatment as “multicomponent care” when one particular form of treatment could not be separately abstracted from other treatment types.

Several studies reported multiple types of care, such as rates of surgery as well as chemotherapy. These studies were reported in both tables on surgery and chemotherapy. As a result, some studies may appear in the data tables more than once. Tables presenting studies with findings on receipt of initial care are organized by cancer site and then by year of publication, beginning with the most recent year of publication. Given the limited number of studies focusing on either post-diagnostic surveillance (n = 7) or end-of-life care (n = 1), findings from these studies are described in the text only.

Results

Study Characteristics

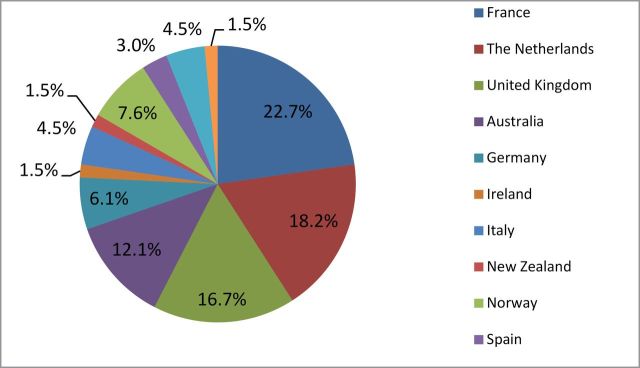

Out of the total 66 papers included in the review, the vast majority focused on initial treatment for colorectal cancer (Table 1). Limited research examined either post-diagnostic surveillance or end-of-life care. With respect to distribution by country, the majority of studies were conducted in France (22.7%), the Netherlands (18.2%), the United Kingdom (16.7%), and Australia (12.1%) (Figure 1). Categories for components of care were not mutually exclusive. Nearly three-quarters of studies reported rates of surgery (69.7%), whereas approximately half of studies reported rates of radiation treatment (48.5%) and chemotherapy (51.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of colorectal cancer care studies from Europe, Australia, and New Zealand (n = 66)

| Characteristics | No. of studies | Percentage of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Study publication year | ||

| 2000–2003 | 16 | 24.2 |

| 2004–2007 | 35 | 53.0 |

| 2008–2010 | 15 | 22.7 |

| Tumor site reported (not mutually exclusive)* | ||

| Colon | 29 | 43.9 |

| Rectum | 45 | 68.2 |

| Colorectal (combined) | 11 | 16.7 |

| Type of care measured | ||

| Initial treatment only | 58 | 87.9 |

| Initial treatment + post-diagnostic surveillance | 5 | 7.6 |

| Post-diagnostic surveillance only | 2 | 3.0 |

| End of life | 1 | 1.5 |

| Component(s) of care reported (not mutually exclusive)* | ||

| Initial care | ||

| Surgery | 46 | 69.7 |

| Radiation | 32 | 48.5 |

| Chemotherapy | 34 | 51.5 |

| Multicomponent | 11 | 16.7 |

| Post-diagnostic surveillance | 7 | 10.6 |

| End-of-life care | 1 | 1.5 |

| Cancer patient identification/data source | ||

| Registry | 20 | 30.3 |

| Medical records/hospital data | 21 | 31.8 |

| Registry + medical records/hospital data | 9 | 13.6 |

| Registry + physician survey | 8 | 12.1 |

| Other | 5 | 7.6 |

| Not reported | 3 | 4.5 |

| Study design | ||

| Retrospective cohort | 54 | 81.8 |

| Prospective cohort | 10 | 15.2 |

| Cross-sectional | 2 | 3.0 |

| Lower-bound year of diagnosis | ||

| Prior to 1990 | 11 | 16.7 |

| 1990–1999 | 28 | 42.4 |

| 2000 and later | 8 | 12.1 |

| Not reported | 19 | 28.8 |

| Age distribution | ||

| Mean/median age <65 | 9 | 13.6 |

| Mean/median age >65+ | 49 | 74.2 |

| Not reported | 8 | 12.1 |

| Number of cancer patients | ||

| <500 | 16 | 24.2 |

| 500–999 | 15 | 22.7 |

| 1000–4999 | 20 | 30.3 |

| 5000–9999 | 5 | 7.6 |

| 10 000+ | 10 | 15.2 |

* Exceeds 100% because some studies counted in more than one category; percentages for components of care and cancer site were derived by dividing reported number of studies by total number of studies (n = 66); several articles examined both colon and rectal cancers separately; therefore, these studies were counted twice when reporting site of cancer.

Figure 1.

Percentage of studies by country.

As shown in Table 2, the data sources for measuring patterns of care varied significantly in terms of population coverage (eg, single institution vs national) and availability of information about cancer diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, and health services reported. Studies from certain countries, such as France and the Netherlands, relied more heavily on registry data, with several studies using the French network of cancer registries (FRANCIM) or the Eindhoven registry as the data source. By contrast, studies conducted in countries such as Italy, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom relied more heavily on hospital data sources that were comprised of either single or multiple institutions. Studies from other countries had mixed data sources that ranged from national health insurance commissions for pharmaceuticals to single institutions to registries in a particular geographic region or area.

Table 2.

Characteristics of selected data sources for measuring patterns of colorectal cancer care in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand*

| Country | Data source | Type of data | Population coverage | Information about cancer patients | Health services reported | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of diagnosis | Stage at diagnosis | Surgery | Chemotherapy | Radiation | ||||

| Australia | Multiple hospitals | Hospital records | Four hospitals in Western Australia; 1.8–2 million | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Victoria Cancer Registry | Registry | State in southeast Australia | √ | √ | ||||

| Health Insurance Commission through PBS | Insurance claims for pharmaceuticals | National | √ | |||||

| France | Burgundy Registry of Digestive Cancers | Registry, physician survey | Region | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Calvados Registry of Gastrointestinal Tumors | Registry | Administrative district in north of France | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| FRANCIM | Registry, hospital data, physician survey | 10% of French population in eight administrative areas | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Multiple hospitals | Medical records | 81 hospitals | Date of surgery | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Germany | Multiple hospitals | Hospital databases/medical records | 75 hospitals in five states: Bradenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, Mecklenberg-West Pomerania | Hospital admission date | √ | |||

| Munich Cancer Registry | Registry | Individuals residing in Munich region, approximately 2.3 million | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Ireland | National Cancer Registry | Registry | NCR records all cancers diagnosed in Ireland and has 98% completeness of registration | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Italy | University of Milan, San Raffaele Hospital | Hospital data | Single hospital in Milan | Date of treatment | √ | |||

| Oncology centers | Forms completed by treating oncologist | 86 Italian oncology centers | NR | √ | √ | |||

| The Netherlands | Netherlands Cancer Registry–National Registry of Hospital Discharges | Cancer registry, national registry of hospital discharge diagnoses, hematology departments and radiotherapy institutions | All malignancies in the Netherlands | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Cancer registry notified by pathology departments, hospital records, and radiotherapy institutes | All malignancies in southern part of the Netherlands, approximately 2.4 million | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Dutch National Medical Registry | Hospital discharge | All hospitalized patients in the Netherlands | Date of surgery | √ | ||||

| New Zealand | Christchurch Hospital | Hospital patient notes | Single hospital in Canterbury region | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Norway | Aker Hospital linked to registry | Hospital data, registry | Single hospital in Oslo catchment of 180 000 | Hospital admission | √ | √ | √ | |

| Norwegian Rectal Cancer Project | Registry, medical records, patient administrative data | Rectal cancer treated with curative intent in one of 47 hospitals | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Spain | Clinico Universitario of Valencia | Registry | Valencia hospital catchment of 275 000 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Sweden | National Quality Registry for Rectal Adenocarcinoma | Registry | 97% of all rectal patients in Sweden since 1995 | √ | √ | |||

| Uppsala/Orebro registries | Registry | Uppsala/Orebro | √ | √ | ||||

| Multiple hospitals | Medical records | County of Vastmanland, five hospitals | Date of surgery | √ | ||||

| United Kingdom | NHS HES dataset | Hospital discharge | All NHS hospitals | Date of surgery | ||||

| NORCCAG; Newcastle and North Tyneside, Northumberland, Gateshead, South Shields, Sunderland, Teesside, County Durham, Cumbria, and part of North Yorkshire | Hospital data | All hospitals in northern region of England, population 3.1 million | √ | |||||

| Hospital | Hospital data | Single hospital, Leeds, England | Date of surgery | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Scottish registry linked to hospital data | Registry, hospital inpatient and day case form data | All hospitals in Scotland | √ | √ | √ | |||

| European collaboration | Cancer registries from the following regions: Genoa and Varese (Italy); Côte-d’Or (France); Granada, Navarra, and Tarragona (Spain); Tampere (Finland); Estonia; Slovenia; Slovakia; and Krakow and Kielce (Poland) | Registry data | Each cancer registry provides detailed information on diagnostic and treatment procedures, obtained from clinical records | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

* FRANCIM = French network of cancer registries; NCR = National Cancer Registry; NHS HES = National Health Service Hospital Episode Statistics; NORCCAG = Northern Region Colorectal Cancer Audit Group; NR = not reported; PBS = Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Initial Treatment

Surgery.

Forty-six articles included in the review reported rates of surgical treatment and spanned several countries (Table 3), including France (19.6%), the United Kingdom (19.6%), Australia (15.2%), and the Netherlands (15.2%). Among studies that were not exclusively limited to patients undergoing surgery, rates of resection varied from 54% to 85% (36,57) depending upon cancer site, stage, patient age, disease stage, and study time period. One study was conducted as a European collaboration comparing rates of resection with curative intent across eight European countries (28) and found significant variation of resection rates by country, ranging from 44% in Kielce (Poland) to 86% in Genoa (Italy).

Table 3.

Patterns of care for the initial surgical treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand by cancer site, publication year, and country (n = 46)*

| First author, y (ref.) | Country | Stage | Year of diagnosis | N | Age (y) | Health delivery setting and data sources | Findings related to initial surgical treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | Lepage, 2006 (49) | France | All stages | 2000 | 567 | Mean at diagnosis 70 | Burgundy Registry of Digestive Cancers | 74.4% curative resection, 15% palliative resection; 3.9% exploratory laparotomy or bypass |

| Morris, 2007 (44) | Australia | Stage II | 1993–2003 | 812 | Mean 64.9 | Four hospitals in Western Australia covering 1.8–2 million people; pathology reports | 82% of the sample received surgery alone | |

| Silvera, 2006 (50) | France | All stages | Hospitalized or surgery 2001–2002 | 1842 | 18+; mean 68.7 | French health insurance database; patients in Paris metropolitan area; surveys of medical advisers | 96.6% had surgery; 89.7% laparotomy; LAP used for 5.9% of operated patients, with conversion to laparotomy for 34% | |

| Phelip, 2005 (63) | France | All stages | 1995 | 1605 | 75+ | FRANCIM and survey given to specialists | Primary tumor resection in 89.6%, ranging from 87.9% to 92.9% by region | |

| Faivre-Finn, 2002 (79) | France | All stages | 1976–1998 | 3389 | NR | Côte d’ Or, Burgundy registry; hospital data, physician surveys among specialists and GPs | 85.2% had resection, rising from 69.3% (1976–1979) to 91.9% (1988–1991) then stable; rates increased among elderly over time (56.4% vs 90.5%); curative resections rose from 56.6% to 81.0%; in multivariate results, younger age, urban residence, non-MET tumor status, and later diagnosis associated with resection | |

| Rectum | Elferink, 2010 (26) | The Netherlands | Non-MET 77.8%; MET 17.4%; NR 4.8% | 2001–2006 | 16 039 | <60: 26.2%; 60–74: 43.4%; 75+: 30.3% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Patients <75 y and diagnosed with T1-M0 tumors who underwent POL or TEM was 34% vs 43% in 75+; more patients <75 y with an M1 tumor had surgical resection of primary tumor vs 75+ (44% vs 31%) |

| Elferink, 2010 (30) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1989–2006 | 40 888 | ≤44: 4%; 45–59: 22%; 60–74: 43%; ≥75: 32% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Among patients <75 y with stages I–III, resections remained stable from 1989 to 2006, but decreased in elderly from 91% (1989–1993) to 81% (2004–2006); among stage IV patients, younger patients had metastasectomy more frequently | |

| Khani, 2010 (27) | Sweden | All stages | Surgery 1993–1996; 1996–1999 | 277 | Period 1 median 70; period 2 median 69 | County of Vastmanland; four district hospitals’ (period 1) or central county hospital’s (period 2) medical records | In period 1, 38% of patients had AR, 8% LAR, 38% APR, and 16% other surgical procedures; in period 2, 3% had AR, 55% LAR, 18% APR, and 24% other procedures | |

| Marwan, 2010 (25) | Australia | All stages | 2005 | 582 | <59: 32.3%; 60–69: 27.3%; 70+: | Victorian Cancer Registry | 23.4% had APR; 53.2% AR; 1.2% total proctocolectomy; 0.2% TEM; and 23% ULAR | |

| Raine, 2010 (31) | United Kingdom | NR | Admitted 1998–2006 | 29 214 | ≥50 | Inpatient treatment HES dataset | 71.9% of patients with surgery had AR; in adjusted analyses, AR more common in women, elderly, higher SES, ER admissions, and in more recent years | |

| Ferenschild, 2009 (33) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1996–2003 | 210 | Mean 69 | Medical charts, including hospital notes, radiotherapy plans, and pathology reports | LAR in 69% and APR in 31% | |

| Martling, 2009 (35) | Sweden | All stages | 1995–2002 | 11 774 | Median women 73; men 71 | National Quality Registry included patient data, adjuvant treatment, surgery | 86.4% had surgical resection; 52.7% AR; 26.9% APR; 10.3% HP; 10.1% other procedures | |

| Sigurdsson, 2009 (37) | Norway | NR | 1997–2002 | 297 | Median 77; range 67–84 | Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Registry | 64% had noncurative surgery, younger patients more likely; in resected patients, 48% major resections, 48% stomas, and 4% local procedures or surgical explorations | |

| Tilney, 2008 (38) | United Kingdom | NR | Admitted 1996–2004 | 52 643 | NR | England; inpatient treatment in HES dataset | 24.9% had APR, which decreased from 29.4% to 21.2% over time; in adjusted analyses, APR less likely among older age, female, higher SES, and ER presentation patients | |

| Ptok, 2007 (42) | Germany | Stages I–III | Entered study 2000–2001 | 1557 | Median 66; range 26–92 | Multisite observational study, data collected from patients, hospital data | APR rate significantly associated with hospital volume | |

| Phelip, 2004 (66) | France | All stages | 1990 and 1995 | 945 | Stratified as <75 and >75 | FRANCIM; survey given specialists and GPs | The proportion with resection increased from 84.6% in 1990 to 91.9% in 1995; patients 75+ and with VM less likely to have surgery; the proportion of TE increased over time (3.2% to 13.2%) | |

| Phelip, 2004 (69) | France | All stages | 1995 | 683 | ≥75: 38.8% | Nine FRANCIM registries; health services data from survey given to gastroenterologists, oncologists, and surgeons | 88.4% had resection; age and distant metastases independently associated with resection; 14.2% of patients had resection without laparotomy, which varied across districts; 36.1% of resected patients had a stoma | |

| Wibe, 2004 (72) | Norway | Stages I–III | Surgery 1993–1999 | 2136 | Median 69 (range 18–94) | Norwegian Rectal Cancer Project; hospital databases/project-specific forms from the Rectal Cancer Registry | 62% of patients had AR, 38% APR; younger patients had AR more often than older patients; individuals with T4 tumors more likely to receive APR | |

| Engel, 2003 (76) | The Netherlands | NR | Surgery 1994–1999 | 15 978 | Peripheral mean 64.9; university 56.6 | Dutch National Medical Registry | Of all rectal resections, 16% were APRs, 84% were RRs; the proportion of APRs decreased from 0.19 to 0.13; the ratio of APR to total resectional rectal surgery (APR plus RR) declined in peripheral hospitals, but not university | |

| Martijn, 2003 (73) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1980–2000 | 3635 | <60: 26.3%; 60–74: 47%; 75+: 26.7% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 53% had surgery only; treatment with surgery alone decreased from 62% to 42% (1980–2000); surgery + radiotherapy increased (26% vs 40%) | |

| Birbeck, 2002 (80) | United Kingdom | NR | Surgery 1986–1997 | 586 | Median 69.6; range 27.9–96.6 | Leeds, United Kingdom; hospital data, case notes from patients with full clinical follow-up | 83.3% of surgeries curative resections; 16.7% palliative | |

| Farmer, 2002 (81) | Australia | Dukes A-C | 1994 | 681 | NR | Victoria Cancer Registry; physician survey completed for each patient | Restorative AR most common procedure (63.3%); other procedures were APR (23.5%) and local excision (5.0%) | |

| Nesbakken, 2002 (83) | Norway | Dukes A-C | Admitted 1983–1999 | 312 | First period mean 72 (range 27–97); second period mean 73 (range 19–95) | Single institution: Aker Hospital in Oslo, Norway; hospital records, pathology reports, and Cancer Registry | In period 1 (1983–1992), 56.5% had curative resection; 58% LAR, 1% HP, and 42% APR; in period 2 (1993–1999), 55.1% had curative resection using ME 67% LAR, 5% HP, and 28% APR; in period 1, 0 patients had either total or partial ME vs 66% TME and 34% PME in period 2 | |

| García-Granero, 2001 (86) | Spain | Dukes A-C; TNM I–III | 1986–1995 | Total 202 | Median 1: 66 (31,88); median 2: 67 (31,85) | Hospital Clinico Universitario of Valencia Health services data from registry (ie, clinical, operative, pathological, and follow-up data) | Period 1 TE was 1.06 vs 2.7 in period 2; radical resectability 67.7 vs. 82.4; APR/overall 25.8 vs 16.7; APR/LAR 54.2 vs 30.5 | |

| Marusch, 2001 (85) | Germany | NR | Presented and admitted 1999 | 1463 | NR | Hospital databases/medical records; patients in states of Bradenburg, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Mecklenberg-West Pomerania | 75 hospitals categorized into three annual rectal surgery volume groups: <20 patients/y (n = 44); 20–40 (n = 22); >40 (n = 9); hospitals treating >40 patients/y have lower APR rate vs lower volume hospitals | |

| Gatta, 2010 (28) | European collaborative study | NR | 1996–1998 | 6871 | ≥75: 3.6%; <75: 66.4% | European cancer registries | 71% treated with curative intent, ranging from 44% in Kielce to 86% in Genoa; proportion treated decreased with advancing age at diagnosis from 76% in patients under 65 y, 73% in 65 to 74, and 63% in patients of 75 and over (P < .001) | |

| CRC | Green, 2009 (32) | United Kingdom | NR | Hospitalizations 1997–2007 | 182 191 | NR | England; inpatient treatment in HES dataset | LAP procedures increased from <1% of all surgeries to approximately 8% over time; in 2000, NICE recommended against LAP surgery, but recommended it in 2006; between 2003–2004 and 2007, LAP surgery increased 2.04% annually |

| Kube, 2009 (36) | Germany | All stages | Resections 2000–2005 | 346 hospitals; 47 436 patients | NR | Hospital data; standardized questionnaire completed at hospital; follow-up survey filled out by patient’s doctor or hospital | Rates of curative resection ranged from 80% to 83% for colon and were nearly 85% for rectal cancer | |

| Carsin, 2008 (90) | Ireland | All stages | 1994–2002 | 15 249 | Patients ≥20 | National Cancer Registry | 78% resection; almost all stage I–III had surgery, 51% of stage IV; among stage IV patients, resection less common in older, unmarried, and male patients in multivariate results | |

| Borowski, 2007 (45) | United Kingdom | All stages | Admitted 1998 and 2002 | 8219 | <65: 28.8%; 65–74: 35.7%; 75–84: 29.2%; >84: 6.3% | NORCCAG; hospital data, histopathology records | 93.8% had resections, including 96.0% of colon and 91.3% rectal tumors; 74·6% had curative resections; older age, comorbidity, ER surgery and rectal cancer associated with nonresection | |

| Young, 2007 (46) | Australia | All stages | February 2000– January 2001 | 2984 | <60: 22.4%; 60–69: 26.26%; 70–79: 33.3%; ≥80: 17.7% | New South Wales; surgeon questionnaire, cancer registry | Of LAR or ultra-LAR patients, 29.1% had a colonic pouch reconstruction | |

| Lemmens, 2006 (52) | The Netherlands | NR | 2002 | 308 | Colon: mean 70, range 41–91; rectal: mean 64, range 33–86 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 55% had LAR; 37% AR; 5% HP; 95% of colon cancer patients had radical surgical treatment; of those with resectable tumors, 89% had curative resection; 20.6% had urgent surgery | |

| Bouvier, 2005 (57) | France | All stages | 1978–1997 | 2409 | 80+ at diagnosis | Calvados and Côte-d’Or registries | 69% of colon, 54% of rectal cancer patients had curative resection, increasing for all sites over time; patients in urban/periurban areas more likely to have resections | |

| Dejardin, 2005 (59) | France | Non-MET 78%; MET 18%; NR 4% | 1995 | 1413 | <65: 30%; 65–74: 35%; 75–84: 25%; >84: 10%; NR: 0.2% |

Six FRANCIM registries | 22.6% treated for initial surgery in reference center site (ie, university or regional comprehensive cancer centers); women less likely to be treated in reference cancer center and less likely to go reference cancer site for surgery, as travel distance increased | |

| Hall, 2005 (55) | Australia | NR | 1982–2001 | 14 587 | <60: 26.6%, ≥60: 73.4% | Western Australia data linkage system; diagnostic codes and registry used to identify patients | 85.5% had a surgical procedure; 41% of these had AR and 59% HEM; in adjusted results, surgery receipt associated with private insurance, private hospital status, younger age, female, and less comorbidity | |

| Lemmens, 2005 (60) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1995–2001 | 6931 | 50+; mean 70 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | TME performed in 20.1% of stage I–II rectal cancer patients and 28.0% of stage III; most patients with stage IV rectal cancer received palliative therapy alone | |

| Robinson, 2005 (64) | New Zealand | All stages; Dukes | 1993–1994 and 1998–1999 | 673 | Median 71–90; 51–70 | Christchurch Hospital; oncology service or hospital discharge codes, patient notes | Surgery by consultant increased from 44% to 82% over the study period | |

| Barton, 2004 (67) | Australia | All stages | 1994–1996 | 370 | Median 68; range 22–98 | Cancer registry and hospital databases; Western Sydney and Wentworth Health Areas | 80.1% had surgery | |

| Bouhier, 2004 (68) | France | All stages | 1990–1999 | 3135 | Mean 70 | Calvados Registry | 90.9% had resections, including 8.8% endoscopic procedures; rate stable over 10-y study period | |

| Jestin, 2004 (70) | Sweden | All stages | 1995–2000 rectal; 1997–2000 colon | 3612 | Mean: colon 72; rectal 71 | Uppsala/Orebro region rectal and colon cancer registries | Colon: 45.2% had rightsided HEM, 10.3% had leftsided HEM, 24.7% sigmoid resection, 6.7% AR, 5.5% HP, 3.3% surgery without resection; rectal: 50.9% had LAR, 24.7% had APR, 1.2% HP, 3.3% surgery without resection | |

| McGrath, 2004 (71) | Australia | All stages | February 1–April 30, 2000 | 1911 | Mean 68; median 70; range 16–100 | All newly reported cases to any state cancer registry in Australia; physician survey | All patients had surgery, most with curative intent (81.8%); laparoscopic approach in 2.9%; AR most common procedure (35.7%); among rectal cancer patients, TME in 64.6% | |

| Duxbury, 2003 (74) | United Kingdom | NR | Surgery 1999–2000 | 211 | NR | Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, Devon, United Kingdom; consecutive patients undergoing surgery at single hospital | Initially, CRC surgeons more likely to have guideline-consistent practice vs non-CRC surgeon (rectal 55% vs 3%; colon 42% vs 22%); following audits, guideline consistency improved (rectal 90% vs. 0%; colon 78% vs 38%) and fewer procedures by non-CRC surgeon | |

| McFall, 2003 (75) | United Kingdom | NR | Surgery 1990–1996 | 892 | NR | Worthing Hospital, United Kingdom; hospital data and medical records | 88% of patients Dukes stage A–C had resection | |

| Campbell, 2002 (78) | United Kingdom | All stages | 1995 and 1996 | 653 | ≤59: 121 (19%); 60–69: 159 (24%); 70–79: 216 (33%); ≥80: 157 (24%) | Scotland cancer registry; hospitals in Grampian or Highland with case notes and clinical data abstracted | 91% had surgery within 1 y of diagnosis; increased stage and increasing age associated with greater likelihood of surgery | |

| McArdle, 2002 (84) | United Kingdom | Dukes A/B | 1974–1979; 1991–1994 | 3200 | 75+: 35% | Glasgow Royal Infirmary; data from medical records/audits | 70% had curative resection; 30% had palliative surgery; females more likely to have curative resection; ER patients less likely to have resection; overall resection higher in later study period | |

| Chiappa, 2001 (87) | Italy | All stages; modified Dukes | Treated 1992–1999 | 346 | Mean 66 (range 23–92) | Single institution; Department of Emergency Surgery, University of Milan, San Raffaele Hospital | 74% of patients had curative resections |

* AR = anterior resection; APR = abdominoperineal resection; ER = emergency room; FRANCIM = French network of cancer registries; GP = general practitioner; HEM = hemicolectomy; HES = hospital episode statistics; HP = Hartmann’s procedure; LAR = lower anterior resection; LAP = laparoscopy; ME = mesorectal excision; MET = metastatic; NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; NORCCAG = Northern Region Colorectal Cancer Audit Group; NR = not reported; POL = polypectomy; RR = rectal resections; SES = socioeconomic status; TE = transanal excisions; TEM = Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery; ULAR = ultralow anterior resection; VM = visceral metastasis.

Most studies reported trends in rates of surgery over time and described variation in rates by patient characteristics (ie, age, gender, socioeconomic status, disease severity, comorbidities), hospital setting or volume, and geographical location. Several studies reported increasing or stable rates of surgery for both colon and rectal cancers over time (27,30,32,36,66,68,79). However, three studies contrasted decreasing trends for abdominoperineal resection (APR) with increasing trends sphincter-sparing surgery (27,83,86). Additionally, a small number of studies compared trends over time to the implementation of guidelines or national consensus statements (32,46,49,52,66,74).

With respect to patient characteristics, several studies found that younger patients were more likely to receive resections (28,30,37,45,55,66,72,78,79). However, other studies indicated mixed findings for rates of surgical treatment by patient age depending upon type of surgery, time period, and disease severity (26,31,79). Studies also reported mixed findings regarding the association of female gender with the likelihood of receiving surgical treatment (31,38,55,84). Although many studies did not report information on patient socioeconomic status, two UK studies found that patients with lower socioeconomic status were less likely to receive surgical treatment (31,38). Additionally, several studies noted that patients with metastatic tumors and comorbidities were often less likely to receive surgical treatment for colorectal cancer (45,55,66,79).

Variation in rates of surgical treatment was also observed by hospital setting and patient volume for several studies. Presentation to the emergency room was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving resections (31,38,45,84). Hospital type, such as private vs public hospital, was associated with variations in surgical treatment patterns (55,59,76). Additionally, higher hospital volume was associated with lower rates of APR in two studies (42,85). A number of studies also highlighted regional variation in rates of surgery for both colon and rectal cancers (57,63,69,79). Although the majority of studies did not report urban/rural residence, two studies found that individuals living in urban areas were more likely to receive surgery (57,79).

Radiation treatment.

The majority of the 32 total studies reporting on patterns of RT were conducted in the Netherlands (25.0%), France (21.9%), Australia (12.5%), Norway (9.4%), and the United Kingdom (9.4%) (Table 4). Rates of overall RT use varied widely, ranging from 1% to 75% in studies reviewed, depending upon patient age, stage of disease, and study time period (57,81). Studies typically reported increasing or stable rates of RT over time; for instance, one study conducted in the Netherlands found a 16% increase over the study period, with 47% receiving RT in 1998–2002 and 63% receiving RT in 2003–2006 (34). Several studies noted the declining rates of postoperative RT balanced by increasing rates of preoperative RT as a general trend over time (27,30,34,43,57,68,73,83,88). This trend was seen for patients of all age groups, although multiple studies indicated that older patients were less likely to receive either pre- or postoperative RT overall (26,28,30,34,48,78,88).

Table 4.

Patterns of radiation treatment for colorectal cancer (CRC) in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand by cancer site, publication year, and country (n = 32)*

| First author, y (ref.) | Country | Stage | Year of diagnosis | N | Age (y) | Health delivery setting and data sources | Findings related to radiation treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectum | Elferink, 2010 (26) | The Netherlands | Non-MET 77.8%;MET 17.4%; Unknown 4.8% | 2001–2006 | 16 039 | <60: 26.2%; 60–74: 43.4%; 75+: 30.3% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | In multivariate analyses, female and older patients and those with lower stage treated at teaching/university hospitals and lower-volume hospitals less likely to have preoperative RT; regional variation also observed |

| Elferink, 2010 (30) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1989– 2006 | 40 888 | ≤44: 4%; 45–59: 22%; 60–74: 43%; ≥75: 32% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Stages II–III patients receiving preoperative RT increased from 1% in 1989–1999 to 68% in 2004–2006 among younger patients and from 1% to 51% among older patients; among stage II–III patients, postoperative RT decreased from 46% to 4% for younger patients and from 23% to 3% for elderly | |

| Khani, 2010 (27) | Sweden | All stages | Surgery 1993–1996; 1996–1999 | 277 | Period 1: median 70, range 30–93; period 2: median 69, range 40–91 | County of Vastmanland; four district hospitals (period 1) or in central county hospital (period 2); medical records | 41% of patients in period 1 received preoperative RT and 49% in period 2 | |

| Ferenschild, 2009 (33) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1996–2003 | 210 | Mean 69; range 40–91 | Medical charts, including hospital, radiotherapy, and operation notes | Almost 25% of patients received preoperative RT | |

| Martling, 2009 (35) | Sweden | All stages | 1995–2002 | 11 774 | Median 73, range 23–99 (women); median 71, range 21–95 (men) | National Quality Registry included patient data, adjuvant treatment, surgery | 46.5% received preoperative RT; women were less likely to receive than men (42.5% vs 50.1%) | |

| Vulto, 2009 (34) | The Netherlands | NR | 1988–2006 | 7767 | All ages; distribution; for rectal cancer patients, NR | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | RT receipt increased from 47% to 63% (1998–2002 vs 2003–2006); postoperative RT use decreased; in 2004, 50% of all patients received preoperative RT; patients >75 had lower rates of RT vs middle-aged patients; geographic variation and large interhospital variation present | |

| Hansen, 2007 (48) | Norway | All stages | Surgery 1993–2001 | 4113 | <50: 3.01%; 50–64: 25.7%; 65–74: 33.4%; 75–84: 30.5%; ≥85: 0.63% | 50 hospitals; six of these had RT departments | 12.5% received RT (6.9% preoperative and 5.6% postoperative); RT rate with younger age and tumor level; patients who had APR or HP received RT three times more often vs those who had AR; total RT rate increased from 4.6% in 1994 to 23.0% in 2001; preoperative RT use higher for those treated in local hospital with RT department | |

| Vulto, 2007 (89) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1996–2002 | — | <70: 55.6%; 70+: 44.4% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 46% of all newly diagnosed patients received RT; 10% received SRT at least once; multivariate analyses showed patients with stage III had SRT more often and patients in the eastern department received PRT more often | |

| Ng, 2006 (51) | United Kingdom | All stages | 1995–1999 | 207 | All ages | Patients from Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, England; data sources NR | 36.2% receiving surgery also received RT; preoperative RT more likely among patients treated by CRC surgeon | |

| Engel, 2005 (65) | Germany | All stages | 1996–1998 | 882 | <70: 62.5%; 70+: 37.4% | Munich Cancer Registry and Munich Field Study | In both UICC II–III patients, 3.5% received RT alone | |

| Vulto, 2006 (53) | The Netherlands | NR | 1988– 2002 | 2836 | NR | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | The proportion with RT increased over time (33% to 43%) | |

| Phelip, 2004 (69) | France | All stages | 1995 | 683 | ≥75: 38.8% | Nine FRANCIM registries; survey of specialists and GPs | Among resected patients, 46.8% had RT | |

| Phelip, 2004 (66) | France | All stages | 1990 and 1995 | 945 | Stratified as <75 and >75 | FRANCIM; survey of specialists and GPs | 42% of patients in 1990 and 47% in 1995 received adjuvant RT; palliative RT receipt more likely among <75 | |

| Wibe, 2004 (72) | Norway | Stages I–III | Surgery 1993– 1999 | 2136 | Median 69, range 18–94 | Norwegian Rectal Cancer Project; hospital databases/project-specific forms from the Rectal Cancer Registry | RT given to 10%; 6% preoperatively and 4% postoperatively; RT used more often in APR vs AR group (16% vs 6%) | |

| Martijn, 2003 (73) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1980– 2000 | 3635 | <60: 26.3%; 60–74: 47%; 75+: 26.7% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Postoperative RT decreased from 2005 to 2010, whereas preoperative RT increased for all tumor stages and all ages; from 1980 to 1989, 25% had postoperative RT and 1% had preoperative RT; by 1995–2000, 4% had postoperative RT vs 35% preoperative RT | |

| Birbeck, 2002 (80) | United Kingdom | NR | Surgery 1986–1997 | 586 | Median 69.6; range 27.9–96.6 | Leeds, United Kingdom; hospital data and case notes from patients with full clinical follow-up | 4.3% received preoperative RT | |

| Farmer, 2002 (81) | Australia | Dukes A-C | 1994 | 681 | NR | Victoria Cancer Registry; physician questionnaire for each patient | Among 153 patients with completed RT survey, 74.5% had RT as adjunct to surgical resection, and of these, 4.4% had preoperative RT vs 95.6% postoperative RT | |

| Nesbakken, 2002 (83) | Norway | Dukes A-C | Admitted 1983–1999 | 312 | Period 1: mean 72, range 27–97; period 2: mean 73, range 19–95 | Single institution: Aker Hospital in Oslo, Norway; hospital records, pathology reports, Cancer Registry | 2% received pre- or post-RT in period 1, whereas 13% received pre- or post-RT in period 2 | |

| Faivre-Finn, 2000 (88) | France | Stage I–III | 1976–1996 | 651 | <65: 22.8%; 65–74: 39.4%; 75+: 37.7% | Cancer registry in Côte d’Or, Burgundy; registry provided both patient and health services data | Overall, adjuvant RT given to 37.3% of resected patients; percent of treated patients increased from 14.3% in 1976–1978 to 61.7% in 1994–1996; preoperative RT increased over time, postoperative RT following surgery increased with higher stage; in multivariate results, later period of diagnosis, younger age, surgery type, and hospital type (university vs private) associated with adjuvant RT | |

| CRC | Gatta, 2010 (28) | European Collaborative Study | NR | 1996–1998 | 6871 | ≥75: 33.6%; <75: 66.4% | Only 12% of stage I–III rectal cancer patients received RT; geographical variation in RT use in multivariate results indicated that patients aged ≥75 were less likely to receive RT than <75 age group | |

| Carsin, 2008 (90) | Ireland | All stages | 1994–2002 | 15 249 | ≥20 | National Cancer Registry | 13% RT (4% colon; 28% rectum); increased by 10% per year; notable increase in preoperative RT after 2000; for all stages, RT decreased with increasing age; women with stage II disease less likely to get RT; tumor extent associated with RT among stage II and unknown stage patients; preoperative RT use less frequent among female patients and decreased with age | |

| Coriat, 2007 (41) | France | All stages | 1998 | 407 | Median 72, range 26–93 | Burgundy Registry of GI Cancers | 43% with a rectal localization received postoperative RT | |

| Mahboubi, 2007 (49) | France | All stages | 1998 | 389 | <65: 26.5%; 65–74: 34.2%; ≥75: 39.3% | Côte-d’Or and Saone-et-Loire registries, Burgundy; medical records, specialists and GP survey | Overall, 14.9% had RT | |

| Young, 2007 (46) | Australia | All stages | February 2000– January 2001 | 2984 | <60: 22.4%; 60–69: 26.3%; 70–79: 33.3%, ≥80: 17.7% | New South Wales Cancer registry; treating surgeon surveys | Of high-risk rectal cancer patients, 59.8% were offered RT | |

| Bouvier, 2005 (57) | France | All stages | 1978–1997 | 2409 | 80+ at diagnosis | Calvados and Côte-d’Or registries | 1% of colon cancer cases and 17% of rectum cases received RT; RT use increased over time | |

| Drug Utilization Review Team in Oncology, 2005 (54) | Italy | NR | Past/current diagnosis October 2000 | 434 | ≤50: 15.2%; 51–60: 25.3%; 61–70: 36.6%; >70: 21.0% | 86 Italian oncology centers; forms completed by treating oncologist | Only seven patients with colon cancer received RT; 61% of rectal cancer patients received adjuvant RT | |

| Gonzalez, 2005 (58) | Spain | All stages | 1996–1998 | 403 | Mean 65.4 (men), 63.8 (women) | Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge in Barcelona, Spain | 18.8% of men and 20.7% of women had RT | |

| Lemmens, 2005 (60) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1995–2001 | 6931 | 50+; mean 70 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Comorbidity influenced adjuvant RT in patients with rectal cancer | |

| Barton, 2004 (67) | Australia | All stages | 1994–1996 | 370 | Median 68; range 22–98 | Western Sydney and Wentworth Health Areas; cancer registry and hospital databases | 6.25% had RT | |

| Bouhier, 2004 (68) | France | All stages | 1990–1999 | 3135 | Mean 70 | Calvados Registry | 53.1% of stage II–III rectal cancers had; preoperative RT given to 90% of these; older patients (≥75 vs <75) less likely to receive RT | |

| McGrath, 2004 (71) | Australia | All stages | All newly reported cases 2000 | 1911 | Mean 68, median 70, range 16–100 | All newly reported cases to any state cancer registry in Australia; physician survey | Of 61 rectal cancer surgeries with local invasion, 86.9% offered RT; 65.6% given preoperative RT; among locally advanced patients who did not have surgery, 76.3% offered RT | |

| Campbell, 2002 (78) | United Kingdom | All stages | 1995 and 1996 | 653 | ≤59: 19%; 60–69: 24%; 70–79: 33%; ≥80: 24% | Scotland cancer registry; hospitals in Grampian or Highland; case notes and clinical data abstracted | 13% had RT within 1 y of diagnosis; higher stage and younger stage associated with RT receipt; RT use for colorectal cancer decreased with increasing distance from cancer center |

* AR = anterior resection; APR = abdominoperineal resection; ER = emergency room; FRANCIM = French network of cancer registries; GI = gastrointestinal; GP = general practitioner; HP = Hartmann’s procedure; MET = metastatic; NR = not reported; PRT = primary radiotherapy; RT = radiotherapy; SRT = secondary radiotherapy; UICC = Union International Cancer Control.

Some studies indicated that later stage of diagnosis and tumor status were significant predictors of RT use, with sicker patients being more likely to have RT administered (26,48,60,78,88). Two studies found that female patients were less likely to receive preoperative RT (26,35). Variation in RT use by hospital setting, hospital volume, and surgery type was also reported by several studies (26,34,48,51,72,88). Lastly, some studies reported regional variation in RT rates (26,28).

Chemotherapy.

Thirty-four studies reported patterns of chemotherapy use for colorectal cancer, and these were most commonly conducted in France (35.3%), Australia (17.6%), the Netherlands (17.6%), and the United Kingdom (8.8%) (Table 5). Overall, chemotherapy use varied substantially between studies, ranging from 0% to 95%, depending upon stage, patient age, and study time period (52,73). The single study making national comparisons between European countries found wide variation by cancer registry, ranging from 24% in Krakow to 73% in Slovakia (28).

Table 5.

Patterns of chemotherapy treatment for colorectal cancer (CRC) in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand by cancer site, publication year, and country (n = 34)*

| First author, y (ref.) | Country | Stage | Year of diagnosis | N | Age (y) | Health delivery setting and data sources | Findings related to chemotherapy treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | van Steenbergen, 2010 (29) | The Netherlands | Stage III | NR | 1637 | <65: 514; 65–74: 539; ≥75: 584 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Proportion of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy decreased with increasing age from 85% among aged <65, 68% for 65–74 y and 17% for ≥75 y; interhospital variation was observed |

| Alter, 2007 (40) | France | Stage II | Surgery, 2000 | 532 | Mean 72 | 81 hospitals; data from medical records | 19.5% had adjuvant chemotherapy; older patients, higher tumor stage, and having a bowel obstruction or perforation associated with adjuvant chemotherapy use; hospital procedure volume, multidisciplinary consult, and mode of hospital funding (private vs public) also associated | |

| Lepage, 2006 (49) | France | All stages | 2000 | 567 | Mean 70 at diagnosis | Burgundy Registry of Digestive Cancers | Adjuvant chemotherapy performed in 0.9% of stage I, 17.6% of stage II, and 54% of stage III patients; palliative chemotherapy in 48.1% | |

| Morris, 2007 (44) | Australia | Stage II | 1993–2003 | 812 | Mean 64.9 among patients receiving surgery alone | Four major hospitals in Western Australia; pathology reports used to identify patients | 18.0% received chemotherapy; 25% of patients ≤65 received chemotherapy compared with 10% of those between 66 and 75 y; patients receiving chemotherapy had tumors often positive for vascular invasion; adjuvant chemotherapy use peaked at 25–30% in late 1990s but decreased to <15% in 2002–2003 | |

| Silvera, 2006 (50) | France | All stages | Hospitalized or had surgery 2001–2002 | 1842 | 18+; mean 68.7 | Paris metropolitan area; French health insurance funds administrative database; survey of medical advisers | Chemotherapy given to 53.1%; 5.8% of patients with stage I received chemotherapy; 37.7% of stage II, 76.9% of stage III, 81.4% of stage IV | |

| Lemmens, 2005 (61) | The Netherlands | Stage III | 1995–2001 | 577 | All patients 65–79; 65–69: 31.4%; 70–74: 34%; and 75–79: 34.6% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 80% of patients 65–69 y received chemotherapy vs 28% among 75–79 y; chemotherapy receipt among elderly increased from 19% to 50% over time, with large interhospital variation; in multivariate analyses, patients of older age, female gender, comorbidity, and lower SES less likely to receive chemotherapy; patients with high-grade tumors and stage IIIB received chemotherapy more often | |

| Phelip, 2005 (63) | France | All stages | 1995 | 1605 | 75+ | FRANCIM and survey given to specialists | Among nonmetastatic patients <75 y who had complete resection, adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 6.8% of stage I, 49.4% of stage II, and 79.6% of stage III patients; among metastatic patients and those without complete resection, palliative therapy in 61.7%; regional differences observed | |

| Faivre-Finn, 2002 (82) | France | All stages | 1989–1998 | 4093 | <65: 24%; 65–74: 30%; 75+: 46% | Côte-d’Or and Saône-et-Loire registries in Burgundy; hospital data from general and specialty practitioners | 18.3% treated with adjuvant chemotherapy; over time, chemotherapy use increased from 3.1% to 24.7%; 26% of eligible patients were treated with palliative chemotherapy, with younger patients and males treated more often; in multivariate results, younger patients, later period and stage of diagnosis significantly more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Faivre-Finn, 2002 (79) | France | All stages | 1976–1998 | 3389 | NR | Côte-d’Or registry, Burgundy; hospital data from general and specialty practitioners | Among stage III patients, adjuvant chemotherapy rose from 4.1% to 45.7%, though increase slower in patients 75+; in multivariate analyses, younger age, later period of diagnosis, and stage II/III disease associated with chemotherapy use; palliative chemotherapy use rose from 4.0% to 34.5% over time and patients <75 more likely to receive palliative therapy | |

| Rectum | Elferink, 2010 (30) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1989–2006 | 40 888 | ≤44: 4%; 45–59: 22%; 60–74: 43%; ≥75: 32% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Proportion of stage III patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy increased sharply, particularly among younger patients; chemotherapy in stage IV patients increased from 21% to 66% for younger patients and from 2% to 25% for elderly patients |

| Sigurdsson, 2009 (37) | Norway | NR | 1997–2002 | 297 | Median 77, range 67–84 | Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Registry | Among patients treated with noncurative intent, 28% of patients received chemotherapy | |

| Engel, 2005 (65) | Germany | All stages | 1996–1998 | 882 | <70: 62.5%; 70+: 37.4% | Munich Cancer Registry and Munich Field Study | In stage II patients, 3.0% received chemotherapy alone compared with 12.8% of stage III patients | |

| Phelip, 2004 (66) | France | All stages | 1990, 1995 | 945 | Stratified as <75 and >75 | FRANCIM; survey of specialists and GPs | Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resection and no metastasis rose from 8.1% to 19.0%; palliative chemotherapy given to 37.5% of patients <75 with advanced stage and rose to 50.0%; 0 patients >75 received palliative chemotherapy | |

| Phelip, 2004 (69) | France | All stages | 1995 | 683 | ≥75: 38.8% | FRANCIM; physician survey | Adjuvant chemotherapy given to 33.2% aged <75 and 4.5% among 75+ with curative surgery | |

| Martijn, 2003 (73) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1980–2000 | 3635 | <60: 26.3%; 60–74: 47%; 75+: 26.7% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Chemotherapy increased from 0% to 10% among stage III patients and from 7% to 30% among stage IV patients | |

| Birbeck, 2002 (80) | United Kingdom | NR | Surgery 1986–1997 | 586 | Median 69.6, range 27.9–96.6 | Leeds, United Kingdom; hospital data, patient case notes with full clinical follow-up | 11.9% received adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Farmer, 2002 (81) | Australia | Dukes A-C | 1994 | 681 | NR | Victoria Cancer Registry; physician survey completed for each patient | Data on chemotherapy limited to 144 patients; in 78% of patients, chemotherapy given postoperatively and to 63.9% within 2 mo of surgery | |

| CRC | Gatta, 2010 (28) | European Collaborative Study | Stages I–III | 1996–1998 | 6871 | ≥75: 33.6%; <75: 66.4% |

European cancer registries | Among stage II colon cancer patients, 22% received adjuvant chemotherapy; receipt varied by age (38% for <65 vs 5% for 75+) and cancer registry; among stage III colon cancer patients, 46% received adjuvant chemotherapy and varied by age (69% for <65 vs 16% for 75+) and cancer registry; in multivariate results among stage III colon cancer patients, older age decreased the odds of receiving chemotherapy |

| Carsin, 2008 (90) | Ireland | All stages | 1994–2002 | 15 249 | Patients ≥20 | National Cancer Registry | 31% had chemotherapy, increased by 10% per year, for all stages; older, unmarried patients less likely to have chemo; among stage III–IV, strong positive effect of year of diagnosis | |

| Coriat, 2007 (41) | France | All stages | 1998 | 407 | Median age 72; range 26–93 | Burgundy Registry of GI Cancers | 27% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Damianovich, 2007 (47) | Australia | 100% metastatic | Received medication 2002–2003 | 1465 | 70+: 23%; 80+: 2% | Health Insurance Commission | For 5-FU refractory patients, oxaliplatin use increased from 48% to 66% and irinotecan use decreased from 52% to 34% between 2002 and 2003; differences greater for younger vs older patients and pattern of use observed across all states; younger patients switched more than older ones; of the 697 patients who started oxaliplatin in 2002–2003, 40% switched to irinotecan | |

| Mahboubi, 2007 (49) | France | All stages | 1998 | 389 | <65: 26.5%; 65–74: 34.2%; ≥75: 39.3%. | Côte-d’Or and Saône-et-Loire registries, Burgundy; medical records and survey of specialists and GPs | Overall, 27.2% had chemotherapy | |

| Young, 2007 (46) | Australia | All stages | 2000–2001 | 2984 | 22.4% <60; 26.3% 60–69; 33.3% 70–79; 17.7% ≥80 | New South Wales; patients identified through cancer registry and had surgery; physician survey | Of Dukes C colon cancer patients who had surgery with curative intent, 76.0% offered chemotherapy | |

| Lemmens, 2006 (52) | The Netherlands | NR | Colon 2002; rectal 2002 | 308 | Colon cancer: mean 70, range 41–91; rectal cancer: mean 64, range 33–86 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 95% of patients <70 received chemotherapy vs 48% 70+ years | |

| Bouvier, 2005 (57) | France | All stages | 1978–1997 | 2409 | 80+ at diagnosis | Calvados and Côte-d’Or registries | 2% colon cancer and 2% rectal cancer patients received chemotherapy; 2.4% stage IV colorectal cancer patients had palliative chemotherapy | |

| Drug Utilization Review Team in Oncology, 2005 (54) | Italy | NR | October 2000 | 434 | ≤50: 15.2%; 51–60: 25.3%; 61–70: 36.6% >70: 21.0% | 86 Italian oncology centers; patient, clinical, disease data from treating oncologist forms | Among colon cancer patients, adjuvant chemotherapy given to 42.5%; tumor stage, type of center (hospital vs university), patient age, and number of nodes removed affected decision to give patients chemotherapy | |

| Gonzalez, 2005 (58) | Spain | All stages | 1996–1998 | 403 | Mean 65.4 (men), 63.8 (women) | Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge in Barcelona, Spain | 42.7% of men and 51.2% of women had chemotherapy | |

| Lemmens, 2005 (60) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1995 to 2001 | 6931 | All patients 50+; mean 70. | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | Among stage III patients, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy given to 82.8% <65, 42.4% of 65–79, 1.2% of 80+; among stage IV patients, chemotherapy decreased from 41.3% among 50–64 to 1.8% among oldest | |

| Robinson, 2005 (64) | New Zealand | All stages | 1993–94 and 1998–99 | 673 | Median 71–90; 51–70 | Christchurch Hospital; oncology database, hospital discharge codes, patient notes | Adjuvant chemotherapy for Dukes stage C patients increased from 21% to 45%; chemotherapy for metastatic disease rose from 2.4% to 23% of stage D and from 2.5% to 36.5% for patients who developed metastases | |

| Barton, 2004 (67) | Australia | All stages | 1994–1996 | 370 | Median 68, range 22–98 | Western Sydney and Wentworth Health Areas; cancer registry and hospital databases | 5% received adjuvant chemotherapy not same time as radiotherapy, whereas 6% received adjuvant chemotherapy alone; among eligible colon cancer patients, 51% received adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Bouhier, 2004 (68) | France | All stages | 1990–1999 | 3135 | Mean 70 | Calvados Registry of GI Tumors | Among colon cancer patients, 21.8% of stage II and 46.9% of stage III patients had chemotherapy; chemotherapy use increased for stage III patients, but remained stable for stage II; among stage IV patients, 45.9% received palliative chemotherapy and this increased over time; older age (75+) associated with decreased chemotherapy use and general hospitals (vs university centers) less likely to treat stage III patients with chemotherapy | |

| McGrath, 2004 (71) | Australia | All stages | 2000 | 1911 | Mean 68, median 70, range 16–100 | All state cancer registries; survey given to surgeons | Chemotherapy offered to more patients with Dukes A, B and C rectal cancer vs colon cancer patients (49.4% vs 39.4%) | |

| Campbell, 2002 (78) | United Kingdom | All stages | 1995–1996 | 653 | ≤59: 19%;60–69: 24%; 70–79: 33%; ≥80: 24% | Scotland cancer registry; hospitals in Grampian or Highland; case notes and clinical data | 23% received chemotherapy within 1 y of diagnosis; higher stage and younger age associated with increased chemotherapy receipt | |

| Pitchforth, 2002 (77) | United Kingdom | NR | 1992–1996 | 7303 | All ages | Scotland cancer registry and services from Scottish morbidity record inpatient and day case form | 13.7% received chemotherapy within 6 mo of first admission; ER admissions less likely to receive chemotherapy; noncancer hospital admittees less likely to get chemotherapy |

* AR = anterior resection; APR = abdominoperineal resection; ER = emergency room; FU = fluorouracil; GI = gastrointestinal; GP = general practitioner; HP = Hartmann’s procedure; LAR = lower anterior resection; MET = metastatic; SES = socioeconomic status; ULAR = ultralow anterior resection.

Many studies noted increasing trends of chemotherapy use over time, particularly toward the later part of the 1990s (30,44,54,64,66,68,73,79,82). Several studies also indicated that younger patients were more likely to receive chemotherapy compared with older patients, though some highlighted rising rates of chemotherapy use among the elderly over time (28–30,40,46,47,60,61,66,68,69,78,79). Additionally, more advanced tumor stage greatly increased the likelihood of chemotherapy receipt (30,40,49,50,54,61,63–66,68,73,78,79).

Although studies exhibited inconsistent reporting of comorbidities, two studies found that patients with previous malignancies or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were less likely to receive chemotherapy (60,61). Chemotherapy receipt was less likely among both women and patients with lower socioeconomic status in one study (61). Several studies also highlighted variation in chemotherapy rates by hospital setting (eg, general vs university; private vs public), hospital volume, and emergency room admissions (29,40,54,61,68,77).

Multicomponent care.

Out of the 11 studies reporting on patterns of multicomponent care, four were conducted in the Netherlands, three in Germany, and the remaining in Australia, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Norway (Table 6). Studies exhibited variation in stage, patient age, and date of diagnosis. Sources of data varied, though data were most commonly from registries (63.6%) (26,30,37,60,65,73,81). Most studies reported on treatment that combined chemotherapy and radiation, such as chemoradiation or neoadjuvant RT combined with chemotherapy. Predominant findings included higher rates of therapy use over time among younger patients and in higher-volume hospitals (26,30,36,42,60).

Table 6.

Patterns of multicomponent care for colorectal cancer in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand by cancer site, publication year, and country (n = 11)*

| First author, y (ref.) | Country | Stage | Year of diagnosis | N | Age (y) | Health delivery setting and data sources | Findings related to multicomponent care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectum | Elferink, 2010 (30) | The Netherlands | All stages | January 1, 1989–December 31, 2006 | 40 888 | ≤44: 4%; 45–59: 22%; 60–74: 43%; ≥75: 32% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Among younger stage II–III patients, neoadjuvant RT + chemotherapy increased from 1% in 1994–1998 to 9% in 2004–2006; elderly stage II–III patients received neoadjuvant RT + chemotherapy 3% less often in 2004–2006 |

| Elferink, 2010 (26) | The Netherlands | Non-MET 77.8%; MET 17.4%; unknown 4.8% | January 1, 2001–December 31, 2006 | 16 039 | <60: 26.2%; 60–74: 43.4%; 75+: 30.3% | Netherlands Cancer Registry | Most patients with T2/T3/T4-M0 tumors had either preoperative RT or neoadjuvant chemoradiation; proportion of patients receiving either preoperative RT or neoadjuvant chemoradiation was higher for <75 vs 75+ | |

| Sigurdsson, 2009 (37) | Norway | NR | 1997–2002 | 297 | Median 77, range 67–84 | Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Registry | Among patients treated noncuratively, 10% had combination of chemotherapy and RT | |

| Ptok, 2007 (42) | Germany | Stages I–III | Entered study 2000–2001 | 1557 | Median 66, range 26–92 | Multisite observational study; data collected from patients, hospital data | Neoadjuvant RT and radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer increased from 6.5% to 25.0% (2000 vs 2005); adjuvant therapy was 53.4% and 49.7%, respectively; higher-volume hospitals had higher rates of neoadjuvant therapy (16.8% vs 9.9%) | |

| Engel, 2005 (65) | Germany | All stages | 1996–1998 | 882 | <70: 551 (62.5%); 70+: 331 (37.4%) | Munich Cancer Registry and Munich Field Study | 9.4% received both pre- and postoperative adjuvant treatment | |

| Martijn, 2003 (73) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1980–2000 | 3635 | <60: 26.3%; 60–74: 47%; 75+: 26.7% | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | 14% had surgery + preoperative RT, 17% surgery + postoperative RT, 5% surgery + systemic treatment, 5% “other” or missing treatment, 5% no treatment; treatment with surgery and radiotherapy increased in 1980–2000 (26% to 40%) | |

| Farmer, 2002 (81) | Australia | Dukes A-C | 1994 | 681 | NR | Victoria Cancer Registry; physician questionnaire | Chemotherapy was combined with postoperative RT in 65.3% | |

| Colorectal | Kube, 2009 (36) | Germany | All stages | Resections 2000–2005 | 346 hospitals; 47 436 patients | NR | Hospital data, standardized questionnaire, follow-up physician survey | Neoadjuvant RT and radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer increased from 6.5% in 2000 to 25.0% in 2005 |

| Drug Utilization Review Team in Oncology, 2005 (54) | Italy | NR | Past or current diagnosis October 2000 | 434 | ≤50: 15.2%; 51–60: 25.3%; 61–70: 36.6%; >70: 21.0%; NR: 1.9% | 86 Italian oncology centers; forms completed by the treating oncologist | 82 patients enrolled were treated with adjuvant therapy; adjuvant RT was administered alongside chemotherapy in 45.8%, sequentially with chemotherapy in 28.8%, alone to 1.7%, and in a nonspecified way in 23.7% | |

| Lemmens, 2005 (60) | The Netherlands | All stages | 1995 to 2001 | 6931 | All patients 50+; mean 70 | Eindhoven Cancer Registry | The proportion of patients with stage II/III rectal cancer who received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy increased from 3.9% in 1995–1999 to 15.9 % in 2001 | |

| McArdle, 2002 (84) | United Kingdom | Dukes A/B | 1974–1979; 1991–1994 | 3200 | 75+: 35% | Glasgow Royal Infirmary; medical records/audits | Of the total, 5% received adjuvant therapy |

* APR = abdominoperineal resection; LAR = lower anterior resection; RT = radiotherapy.

Post-Diagnostic Surveillance and End-of-Life Care

Seven studies reported information on post-diagnostic surveillance for colorectal cancer, including colonoscopy use, carcinoembryonic antigen testing, chest X-rays, abdominal computed tomography scans or X-rays, and positron emission tomography scans (data not shown) (39,41,49,52,56,62,75). Five studies reported rates of post-diagnostic surveillance in addition to some form of initial care (eg, surgery, chemotherapy), whereas two studies reported exclusively on post-diagnostic surveillance. Studies varied by timeframe for receipt of follow-up care, ranging from 1 year after diagnosis to 3 years post-diagnosis. Notable findings included that patients with advanced-stage cancers and those receiving chemotherapy were more likely to receive follow-up care (39,41). Additionally, variation in post-diagnostic surveillance by physician type (specialist vs general practitioner) and assessment of guideline compliance were also highlighted (39,41,62). The one study conducted in Italy assessing end-of-life care examined patients who died in 2003–2005 and called for guidelines to be created for chemotherapy use among end-of-life patients (data not shown) (43).

Discussion

This systematic review examined patterns of colorectal cancer care in several European countries, Australia, and New Zealand, and was written as a companion to a review on care patterns in the United States and Canada (91). Included studies spanned over 15 countries and focused on initial care for colorectal cancer, including surgery, RT, and chemotherapy. Similar to the United States and Canada review, our analysis revealed limited information on post-diagnostic surveillance and end-of-life care for colorectal cancer (91), representing potential areas where additional research is needed (39,41,43,49,52,56,62,75). Furthermore, existing studies on end-of-life care have included multiple types of cancer patients, and the extent to which colorectal cancer patients have specific end-of-life care needs is not well understood.

In our analyses of study findings for initial care, there were several findings that were common among studies on surgery, chemotherapy, RT, and multicomponent care. These findings included changing trends over time and variation in rates of treatment by patient demographic and health characteristics (ie, age, gender, socioeconomic status, tumor stage, metastatic tumor status, presence of comorbidities), hospital setting and volume, and region (26,28–30,34,36–38,40,42,45,46–48,55,60,61,66,68,69,72,78,79,88). Among these characteristics, patient age was one of the most consistent findings associated with treatment receipt, with older patients being less likely to receive colorectal cancer care compared with younger patients. This finding may be tied to underrepresentation of elder patients in clinical trials, creating challenges for physicians to determine appropriate treatment for older individuals.

Over time, there were also changing trends in specific treatment types. For example, several studies reported lower rates of APR over time and increasing use of sphincter-sparing surgeries, such as total mesorectal excision and lower anterior resection. This change has particular relevance for quality of life among rectal cancer patients. Several studies also noted increasing use of preoperative RT alongside decreasing rates of postoperative RT among rectal cancer patients. Chemotherapy rates also increased over time, especially toward the later part of the 1990s.

Of critical importance, we found wide variation in data sources used across studies both between and within countries, making direct comparisons of patient and health services information for initial care challenging. Because of lack of comparability of data reporting and differences in patient populations, comparing rates of surgery, RT, or chemotherapy for colorectal cancer between countries was difficult, and patterns of care identified were incongruous. In this review, the studies that were more amenable to comparisons had greater similarities in type of treatment assessed and patient demographic and clinical characteristics (eg, stage III colon cancer patients). These factors should be considered in future research and data collection efforts.

Moreover, studies had multiple sources of data, ranging from registries to single or multiple institutions. Although studies from particular countries such as France and the Netherlands relied heavily on registry data, others used medical records and hospital data or a mixture of data sources. However, there were varied degrees of population coverage and representativeness even within countries using registry data (eg, FRANCIM). Studies from several countries also did not appear to use centralized registry information. Furthermore, increased linkages between health insurance systems and cancer registry data to provide more detailed information on service utilization patterns may improve current data collection efforts.

Studies also had variability in reporting clinical characteristics that significantly affect treatment and survival as well as variation in time period that trends were assessed. Strikingly, 20% of studies did not report stage of cancer at diagnosis—a fundamental determinant of appropriate cancer treatment. Another important clinical characteristic that was omitted from nearly one-third of studies was year of diagnosis. Additionally, assessment of comparability was limited by reporting of treatment rates for initial care from distinct, disparate, and wide intervals of time, ranging from 1974 to 2006, across studies (26,84).

Further complicating the ability to make comparisons across countries, few studies assessed care in relation to guidelines or other standards, and those which included this information used disparate guidelines for care receipt. Among the studies that discussed use of guidelines, articles compared trends over time for guideline implementation, but used different sets of guidelines or national consensus conference statements (32,39,41,43,62,74). One study also highlighted better guideline-consistent performance among colorectal cancer surgeons compared with other surgeon types (74). Although the creation of guidelines is challenging given the diversity of patient populations and physician practice patterns, efforts could potentially be made to improve consistency of treatment with guidelines among stage III colon cancer patients or stages II–III rectal cancer patients where greater consensus exists.

Notably, many studies omitted important patient characteristics, which are associated with receipt of treatment, including comorbidities, gender, socioeconomic status, urban/rural residence, and patient race/ethnicity or country of origin. Several countries included in this review (ie, England, France, Australia, Germany) have significant immigrant populations and racial or ethnic diversity among the general population (92,93). In addition, variables related to care coordination (ie, the process of linking patients to timely care throughout the process of treatment), quality of care, case-mix, and social support were missing from nearly all studies. Each of these factors has a potentially important role in treatment receipt and utilization of services, and may vary by patient clinical and demographic characteristics, geographical region, and hospital setting.

It should also be noted that many studies had important limitations. Selection bias and limited geographical coverage were present in several studies. For instance, single-institution studies within a country limit generalizability of findings to other geographical areas. Among studies using registry data, such as those in France, the Netherlands, and Australia, population coverage varied widely both between and within each country.

Although this systematic review made significant efforts to thoroughly evaluate existing literature on patterns of colorectal cancer care, some limitations should be noted. Our search terms and criteria used could have unintentionally resulted in exclusions of relevant studies. However, as an effort to maximize the inclusion of relevant studies, reference lists of identified papers and published reviews were evaluated to identify additional articles. In addition, articles were limited to those published in English, which may have missed relevant studies published in other languages.

These limitations notwithstanding, this review had several important findings and implications. This synthesis of the literature summarizes a large number of studies focusing on colorectal cancer care in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, and can be used to identify new directions for future research. For instance, one of the primary gaps in existing literature identified by this review was lack of information on post-diagnostic surveillance and end-of-life care among colorectal cancer patients. Another central finding was significant variation in sources of data for colorectal cancer treatment across studies, which varied by patient demographic and health characteristics, study time period, geographic location, and hospital setting. Therefore, future research and policy efforts should minimize inconsistencies in measurement and emphasize standardization of data reporting for colorectal cancer care.

Additional research is also needed that collects and compares standardized data from multiple European nations, such as EUROCARE, which improve data comparability by using similar standards and quality control measures for registration, data collection, and follow-up of patients within cancer registries (3). Researchers and policy makers from individual countries should further work toward increased representativeness and generalizability of data on colorectal cancer treatment between geographical regions within individual nations. Targeted research and policy efforts in these areas will help to harmonize data sources for comparable analyses and allow for improved assessment of care practices globally.

Appendix

| Search # | Limits: English, Journal Article, Humans, Publication Date from 2000 to 2010 |

|---|---|

| 1 | (“Colorectal Neoplasms/drug therapy”[MeSH] OR “Colorectal Neoplasms/radiotherapy”[MeSH] OR “Colorectal Neoplasms/surgery”[MeSH] OR “Colorectal Neoplasms/therapy”[MeSH]) |

| 2 | “Physician’s Practice Patterns”[MeSH] |

| 3 | “Guideline Adherence”[MeSH] |

| 4 | “Health Services/statistics and numerical data”[Majr] OR “Health Services/trends”[Majr] OR “Health Services/utilization”[Majr]) |

| 5 | “Quality of Health Care/statistics and numerical data”[Majr] OR “Quality of Health Care/trends”[Majr] OR “Quality of Health Care/utilization”[Majr] |

| 6 | “Chemotherapy, Adjuvant/statistics and numerical data”[MeSH] OR “Chemotherapy, Adjuvant/trends”[MeSH] OR “Chemotherapy, Adjuvant/utilization”[MeSH] |

| 7 | “Neoadjuvant Therapy/statistics and numerical data”[MeSH] OR “Neoadjuvant Therapy/trends”[MeSH] OR “Neoadjuvant Therapy/utilization”[MeSH] |