“Targeting PRAME by combination therapies with siRNA and retinoids or by future immune therapies is expected to simultaneously eliminate tumor cells and cancer-initiating cells, arresting tumor progression.”

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) are the most common cancers of the head and neck region. In 2002, WHO estimated that 600,000 new cases of head and neck cancer and 300,000 deaths per year occur worldwide, with a projection of 595,000 deaths in 2030 [1]. Thus, HNSCCs are of considerable clinical and socioeconomic relevance. The standard of care therapy for HNSCC includes surgery, surgery plus chemoradiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy alone. Despite substantial progress in surgical and therapeutic strategies, the 5-year survival of patients with HNSCC has not improved, and recurrence as well as cancer resistance to therapy are major problems [2]. The ability to predict recurrence and/or response to therapy depends on the use of biomarkers. Unfortunately, no reliable prognostic biomarkers of outcome or response to therapy are available for HNSCC, and the search for clinically relevant biomarkers is currently a priority. The expectation is that the availability of biomarkers, which can reliably identify patients with potentially poor outcome, will inform future selection of therapies and facilitate chemoprevention [3].

PRAME as a potential prognostic biomarker in HNSCC

A number of molecular markers associated with HNSCC progression have been reported [4], including EGFR, EGFRvIII and p53, but none have been validated so far as a reliable biomarker of HNSCC outcome. Recently, attention has turned to PRAME, a tumor-associated antigen (TAA) and a member of the cancer D testis antigen family [5]. In addition to melanoma, PRAME (Gene ID: 75829) is expressed in a wide variety of human tumors, and has been extensively studied in hematological malignancies [6]. Importantly, PRAME is only weakly or not at all expressed in normal tissues. Further more, PRAME has been reported to induce cytotoxic T-cell-mediated immune responses in melanoma [5], and thus represents a promising target for TAA-specific immune therapies.

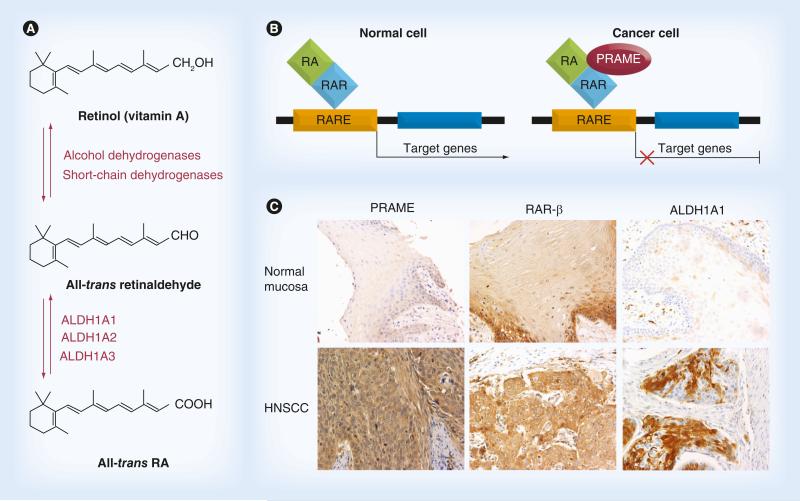

PRAME is also emerging as an important component of the retinol pathway, which is known to regulate various aspects of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and vertebrate development [7,8]. It has been suggested that PRAME contributes to cancer development and progression by interfering with the metabolic pathway of all-trans retinol (vitamin A) and its active metabolites, retinal, β-carotene, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), and 9-cis and 13-cis retinoic acids, collectively known as retinoids (Figure 1A). Retinoids have been used in multiple clinical trials, including those designed for pre-malignant and malignant HNSCC [9–11]. ATRA and its metabolites exert their functions through the two distinct classes of receptors: retinoid acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs). Each receptor class contains three isoform types: α, β, and γ, expressed on various cells. RARs and RXRs form heterodimers upon ligand binding and, functioning as ligand-dependent transcription factors, activate their downstream effectors by binding to the retinoid acid (RA) response elements located in the 5′-region of the RA gene. Activation of this pathway triggers cell differentiation, proliferation arrest and eventually apoptosis. For this reason, retinoids have been extensively investigated in cancer [12]. Among the three RAR isoforms, RAR-β is best known for its tumor suppressive effects in epithelial cells [10]. PRAME is a dominant repressor of RAR signaling. It prevents ligand-induced receptor activation upon binding to RAR in the presence of RA (Figure 1B). Thus, cancer cells over expressing PRAME acquire a survival advantage and are able to escape from RA-induced cell growth arrest. PRAME might also promote malignant differentiation of CD44+/CD24− or ALDH1A1+ cancer-initiating cells (CICs) [13,14]. Therefore, it is likely that a loss of RA responsiveness associated with PRAME overexpression in cancer cells benefits not only malignant cells but also precancerous cells [10,14]. Importantly, all three major proteins in RA metabolism, including ALDH1A1, RAR-β and PRAME, were found to be overexpressed in HNSCC (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we have found coexpression of ALDH1A1 and PRAME in CICs [Szczepanski MJ, Luczak M, Whiteside TL, Unpublished Data]. These observations suggest that adjuvant therapies targeting PRAME might also target CICs.

Our studies of HNSCC cell lines showed that PRAME protein and mRNA were overexpressed in tumor cells but not in normal keratinocytes (HaCaT cells) [15]. Also, PRAME silencing with siRNA in HNSCC cells followed by co incubation with clinically relevant concentrations of RA decreased in vitro migration of these cells and induced their apoptosis [Szczepanski MJ, Luczak M, Whiteside TL, Unpublished Data]. PRAME overexpression in HNSCC tissue specimens, as determined by immunohistochemistry, correlated with the conventional markers of poor prognosis such as a large tumor size, high tumor grade and lymph node involvement. Furthermore, PRAME was found to be overexpressed in HNSCC of patients with advanced disease (stages III and IV). In aggregate, these data suggested that elevated PRAME expression in HNSCC could potentially serve as a biomarker of poor outcome and as a future therapeutic target [15].

Retinoids & PRAME in chemoprevention of HNSCC

The utilization of retinoids in HNSCC chemoprevention has a long history. Precancerous lesions of the head and neck, that is, leukoplakia or erythroplakia, are a well-recognized risk factor for the development of cancer [16]. Several potential chemopreventive agents have been evaluated in HNSCC, including vitamin A (retinylpalmitate), other retinoids, selenium, vitamin E and COX-2 inhibitor)[17]. A randomized trial involving tobacco users with oral leukoplakia supplemented with 200,000 IU of vitamin A every week for 6 months has shown complete remissions in 57% and a progression arrest in 100% of the treated group as opposed to 3 and 21% in the placebo group, respectively [18]. In another study, complete or partial remissions of premalignant lesions have been observed in 45% of patients treated with one of three different retin oids after a 6-year follow-up. Unfortunately, this therapy had considerable toxicity [9].

“...elevated PRAME expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma could potentially serve as a biomarker of poor outcome and as a future therapeutic target.”

Overall, results of clinical trials with retinoids in oral leukoplakia were cautiously promising and encouraged investigations into the mechanistic underpinning of these therapeutic responses.In a small study, we have evaluated PRAME expression in precancerous dysplastic lesions of the head and neck obtained from 12 patients [15]. Only 8/12 patients (66%) were positive for PRAME. Considering the role of PRAME in the RA metabolism, as described above, we tentatively suggested that only patients with the premalignant lesions negative for PRAME are likely to be responsive to retinoid therapy and may be the best potential candidates for chemoprevention with retinoids [15]. While this suggestion was based on results of a very small study, it emphasizes the potentially important role of PRAME expression in the future selection of HNSCC patients for chemopreventive therapy.

PRAME in adjuvant therapy of patients with HNSCC

The efficacy of retinoids in the adjuvant therapy of HNSCC was extensively studied in the past. However, in contrast to effectiveness of ATRA in leukemias [19], retinoids did not reliably improve the outcome in HNSCC. For example, in a Phase III study involving 103 patients with stage I–IV HNSCC, who received either 50–100 mg/m2 isotretinoin daily or a placebo, no significant differences in the frequency of secondary primary tumors or in the number of local, regional or distant recurrences of the primary cancers were observed [20]. Despite the prominent RAR-β expression in human HNSCC (Figure 1C) and in contrast to patients with premalignant lesions, retinoid therapies have been largely ineffective in patients with HNSCC. Although low-dose retinoids showed limited therapeutic effectiveness [17], significant toxicity of high- dose retinoids has further hindered their use in HNSCC therapy. In view of prominent PRAME overexpression in HNSCC, this lack of therapeutic efficacy with retinoids is not surprising. It suggests that a consideration of quite different therapeutic strategies targeting PRAME might be in order. Preclinical studies aimed at decreasing PRAME expression in cancer cell lines by delivery of PRAME-specific siRNA resulted in a cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [6].

PRAME is a member of a large family of the CT antigens, many of which are immunogenic and have served as target antigens in antitumor vaccination clinical trials [21]. Although to the best of our knowledge PRAME-based vaccines have not been so far tested in clinical trials, preclinical studies confirm that PRAME can induce cytolytic T lymphocytes with antitumor activity [22]. Given that PRAME is frequently and selectively overexpressed in HNSCC, its utilization as an effective immunogen in anti- tumor vaccines or, alternatively, adoptive transfers of PRAME-specific T cells, might result in positive immunologic and possibly also clinical responses, especially when immunotherapy is followed by retinoid-based therapy. This expectation is further supported by recent insights into the sensitivity of CICs to tumor antigen-reactive cytolytic T lymphocytes in an experimental animal model of HNSCC [23]. Flow cytometry performed in our laboratory demonstrated that cancer-initiating cells coexpressed PRAME and ALDH1A1. Therefore, it might be expected that immunotherapies targeting PRAME and delivered in the form of peptides or proteins pulsed on antigen-presenting cells plus an adjuvant or retinoid might become an efficacious therapeutic modality for HNSCC patients in the future.

Future perspective

PRAME is emerging as a biomarker of outcome in HNSCC. At this time, more extensive studies are necessary to validate the existing correlations of PRAME expression with the conventional prognostic clinicopathologic criteria [15] and to confirm the role of PRAME as a reliable prognostic biomarker in HNSCC. Evidence for PRAME overexpression in HNSCC has provided a partial explanation for the paucity of therapeutic successes with retinoids in the past. The future therapeutic strategies for HNSCC will be based on new molecular insights into PRAME expression in tumors, its ability to be processed and presented by antigen-presenting cells and to induce effective immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Targeting PRAME by combination therapies with siRNA and retinoids or by future immune therapies is expected to simultaneously eliminate tumor cells and CICs, arresting tumor progression. In chemoprevention, selection of patients with PRAME-negative premalignant lesions for retinoid-based preventive treatments might result in better clinical responses.

Figure 1. Role of ALDH1A1, PRAME and retinoid acid receptors in retinoid acid metabolism and expression of these molecules in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas.

(A) The RA metabolic pathway. (B) An interaction between PRAME and RAR. In normal (PRAME−) cells, upon binding of RA to the RAR, a coactivator complex (RARE) is recruited and induces transcription of the target genes responsible for cell cycle arrest, differentiation and apoptosis. In cells expressing PRAME, the induction of transcription is blocked due to constitutive repression of RA signaling by PRAME. (C) Immunohistochemistry showing expression of ALDH1A1, RAR-β and PRAME in normal mucosa and in HNSCC (magnification: ×200).

HNSCC: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; RA: Retinoic acid; RAR: Retinoid acid receptor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH Grant PO-1CA 109688 to TL Whiteside and by the Foundation for Polish Science (Homing Plus/2010-1/13) and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (NN401047738) grant to MJ Szczepanski.

Biography

Miroslaw J Szczepanski

Miroslaw J Szczepanski

Theresa L Whiteside

Theresa L Whiteside

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mathers CC, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forastiere A, Koch W, Trotti A, Sidransky D. Head and neck cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345(26):1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer CC. Exploring biomarkers in head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(16):3882–3892. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calli C, Calli A, Pinar E, Oncel S, Tatar B. Prognostic significance of p63, p53 and ki67 expression in laryngeal basaloid squamous cell carcinomas. B-ENT. 2011;7(1):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka N, Wang YH, Shiseki M, Takanashi M, Motoji T. Inhibition of PRAME expression causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in leukemic cells. Leuk. Res. 2011;35(9):1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, Carlée L, Hernandez M, Bernards R. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122(6):835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epping MM, Bernards R. A causal role for the human tumor antigen preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma in cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10639–10642. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schantz SS. Chemoprevention strategies: the relevance of premalignant and malignant lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 1993;17F:18–26. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240531004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lotan R, Xu XC, Lippman SM, et al. Suppression of retinoic acid receptor-beta in premalignant oral lesions and its up-regulation by isotretinoin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332(21):1405–1410. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng L, Wang Z. Clinical trials in chemoprevention of head and neck cancers. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials. 2012;7(3):249–254. doi: 10.2174/157488712802281349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddikuzzaman, Guruvayoorappan C. Berlin Grace VM. All trans retinoic acid and cancer. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2011;33(2):241–249. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2010.521507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li RJ, Ying X, Zhang Y, et al. All-trans retinoic acid stealth liposomes prevent the relapse of breast cancer arising from the cancer stem cells. J. Control. Release. 2011;149(3):281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudas LL, Wagner JA. Retinoids regulate stem cell differentiation. J. Cell Physiol. 2011;226(2):322–330. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szczepanski MJ, DeLeo AB, Luczak M, et al. PRAME expression in head and neck cancer correlates with markers of poor prognosis and might help in selecting candidates for retinoid chemoprevention in pre-malignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(2):144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele TO, Meyers A. Early detection of premalignant lesions and oral cancer. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2011;44(1):221–229. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhee JJ, Khuri FF, Shin DM. Advances in chemoprevention of head and neck cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9(3):302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-3-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stich HF, Hornby AP, Mathew B, Sankaranarayanan R, Nair MK. Response of oral leukoplakias to the administration of vitamin A. Cancer Lett. 1988;40(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(88)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown G, Hughes P. Retinoid differentiation therapy for common types of acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. Treatment. 2012;2012:939021. doi: 10.1155/2012/939021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benner SE, Pajak TF, Lippman SM, Earley C, Hong WK. Prevention of second primary tumors with isotretinoin in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: long-term follow-up. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994;86(2):140–141. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bioley G, Guillaume P, Luescher I, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant protein encoding the tumor-specific antigen NY-ESO-1 elicits an A2/157–165-specific CTL repertoire structurally distinct and of reduced tumor reactivity than that elicited by spontaneous immune responses to NY-ESO-1-expressing tumors. J. Immunother. 2009;32(2):161–168. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31819302f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amir AL, van der Steen DM, van Loenen MM, et al. PRAME-specific allo-HLA-restricted T cells with potent antitumor reactivity useful for therapeutic T-cell receptor gene transfer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(17):5615–5625. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visus C, Wang Y, Lozano-Leon A, et al. Targeting ALDH(bright) human carcinoma-initiating cells with ALDH1A1-specific CD8+ T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(19):6174–6184. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]