Abstract

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations cause a variety of mitochondrial disorders for which effective treatments are lacking. Emerging data indicate that selective mitochondrial degradation through autophagy (mitophagy) plays a critical role in mitochondrial quality control. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase activity can activate mitophagy. To test the hypothesis that enhancing mitophagy would drive selection against dysfunctional mitochondria harboring higher levels of mutations, thereby decreasing mutation levels over time, we examined the impact of rapamycin on mutation levels in a human cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) cell line expressing a heteroplasmic mtDNA G11778A mutation, the most common cause of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Inhibition of mTORC1/S6 kinase signaling by rapamycin induced colocalization of mitochondria with autophagosomes, and resulted in a striking progressive decrease in levels of the G11778A mutation and partial restoration of ATP levels. Rapamycin-induced upregulation of mitophagy was confirmed by electron microscopic evidence of increased autophagic vacuoles containing mitochondria-like organelles. The decreased mutational burden was not due to rapamycin-induced cell death or mtDNA depletion, as there was no significant difference in cytotoxicity/apoptosis or mtDNA copy number between rapamycin and vehicle-treated cells. These data demonstrate the potential for pharmacological inhibition of mTOR kinase activity to activate mitophagy as a strategy to drive selection against a heteroplasmic mtDNA G11778A mutation and raise the exciting possibility that rapamycin may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of mitochondrial disorders associated with heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations, although further studies are needed to determine if a similar strategy will be effective for other mutations and other cell types.

INTRODUCTION

Disorders caused by maternally inherited pathogenic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations can lead to a wide array of neurological, cardiac and other disorders (1,2). MtDNA mutations also have been linked to cancer and aging (3–6). Characterized by retinal ganglion neuron degeneration and bilateral, painless, subacute visual failure in young adults, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) was the first human disorder shown to be caused by an mtDNA point mutation (7,8). Found in at least 50% of LHON cases, the G11778A mutation that results in a substitution of a highly conserved arginine for a histidine at amino acid position 340 in the ND4 subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) was the first and most common pathogenic point mutation linked to LHON (8,9).

Unfortunately, clearly effective clinical treatments for these often devastating disorders are lacking. An ideal strategy would eliminate the mutant mtDNA and replace it with wild-type (WT) mtDNA. However, classic ‘gene therapy’ approaches are difficult to apply to mtDNA mutations because the uniqueness of the mitochondrial genome, such as the presence of hundreds or thousands of copies of the mitochondrial genome per cell, the challenge of delivery of genes across the double membrane of the mitochondria and the fact that many mtDNA mutations effect multiple tissues throughout the body (10). In the case of heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations, for which a mix of mutant and WT mtDNA are present within the same cells, a potential strategy would be to promote the selective elimination of mutant mtDNA. Mitochondria undergo frequent turnover (every few days), even in postmitotic cells, with only a subset of copies of the mitochondrial genome being replicated during this process, providing an opportunity to influence which mtDNA molecules are replicated. Studies over the past several years have demonstrated that this process of mitochondrial turnover is not random. Dysfunctional mitochondria are preferentially targeted for autophagy–lysosomal degradation, a process known as ‘mitophagy’ (11,12). Mitophagy is predicted to lead to preferential degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria (e.g. due to high levels of deleterious mtDNA mutations). Mitophagy is upregulated as an apparently protective response to rotenone (13), a toxin that inhibits mitochondrial complex I and induces increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and in response to ABT-737, which associates with the mitochondrial membrane and causes depolarization (14). That dysfunctional mitochondria can be selectively targeted for macroautophagic degradation became clear from studies on reticulocyte maturation (14), where mitochondrial removal is greatly impaired in mice lacking the Nix gene, an essential gene in autophagic maturation. In PARKIN-induced mitophagy, removal of impaired mitochondria is blocked in cells missing an essential autophagy gene ATG5, and by treatment with autophagy inhibitors bafilomycin A1 and 3-methyladenine (15). Further, mice with a dysfunctional autophagic pathway accumulate morphologically and functionally impaired mitochondria, suggesting that mitophagy is necessary to maintain mitochondrial quality (16,17).

In a cell with a heteroplasmic pathogenic mtDNA mutation, upon fission, a separated mitochondrion that has predominantly mutant mtDNA will be less likely to maintain membrane potential and more likely to produce elevated ROS, increasing the probability that it will be targeted for mitophagy. We therefore hypothesized that stimulating mitophagy would tend to promote the preferential elimination of mitochondria harboring higher levels of the mutation. Over time, this would promote a progressive reduction in levels of the pathogenic mutation. To test this hypothesis, we established cybrid cell lines expressing a heteroplasmic G11778A mtDNA mutation and treated them for up to 20 weeks with rapamycin, an FDA approved immunosuppressant and anti-cancer drug that has been shown to stimulate mitophagy by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (18), and followed the impact on levels of the mutation.

RESULTS

Chronic rapamycin treatment inhibited mTOR kinase activity

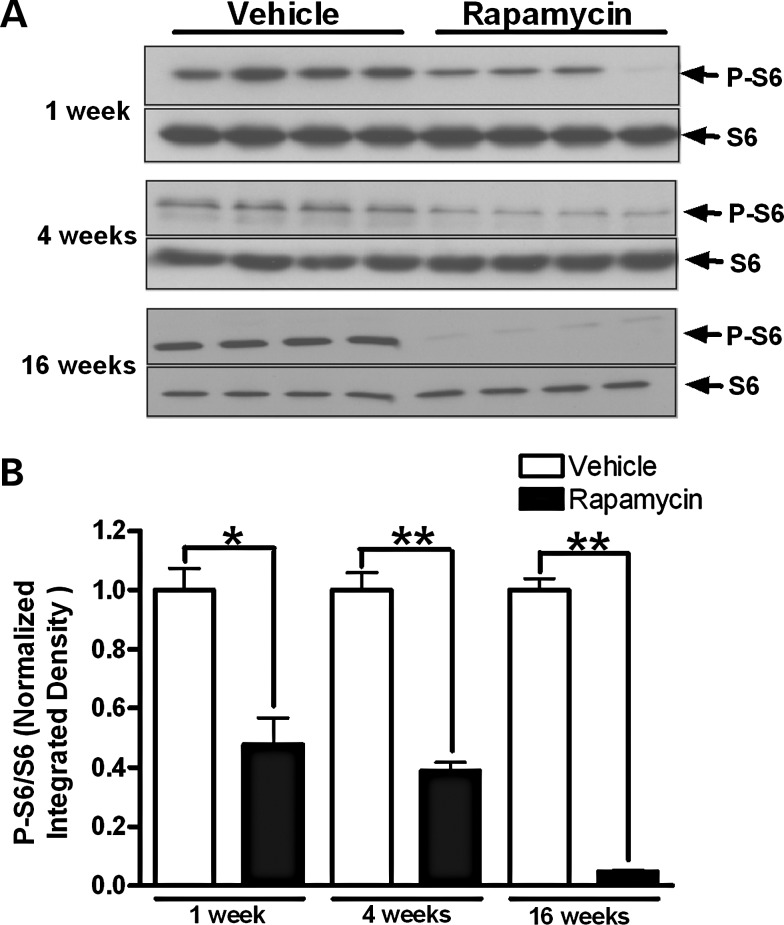

Inhibition of mTOR kinase activity was measured by phosphorylation levels of ribosomal protein subunit S6, which is a target substrate for S6 kinase in the mTOR kinase pathway. Heteroplasmic cybrid cells with ∼75% G11778A mutational burden at baseline were treated with 20 nm (18.3 μg/l) rapamycin, which is in the therapeutic range for serum levels (5–20 μg/l) when used clinically as an immunosuppressant (19). One and four weeks of rapamycin treatment caused a 52 and 61% reduction in phosphorylation of S6, respectively, while 16 weeks of treatment reduced phosphorylation of S6 by more than 95% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

mTOR inhibition by long-term treatment of rapamycin. (A) Cybrid cells expressing the G11778A mutation with an initial mutational burden of 75% were treated with 20 nm rapamycin or vehicle for 1, 4 and 16 weeks. Cells were lysed at the indicated time points and analyzed by immunoblotting for phosphorylated S6 (P-S6) and total S6. (B) Bars represent the P-S6/S6 band densitometry ratios normalized to the vehicle-treated control group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.0001 by Student's t-test.

MtDNA mutational burden in heteroplasmic cells was reduced by rapamycin

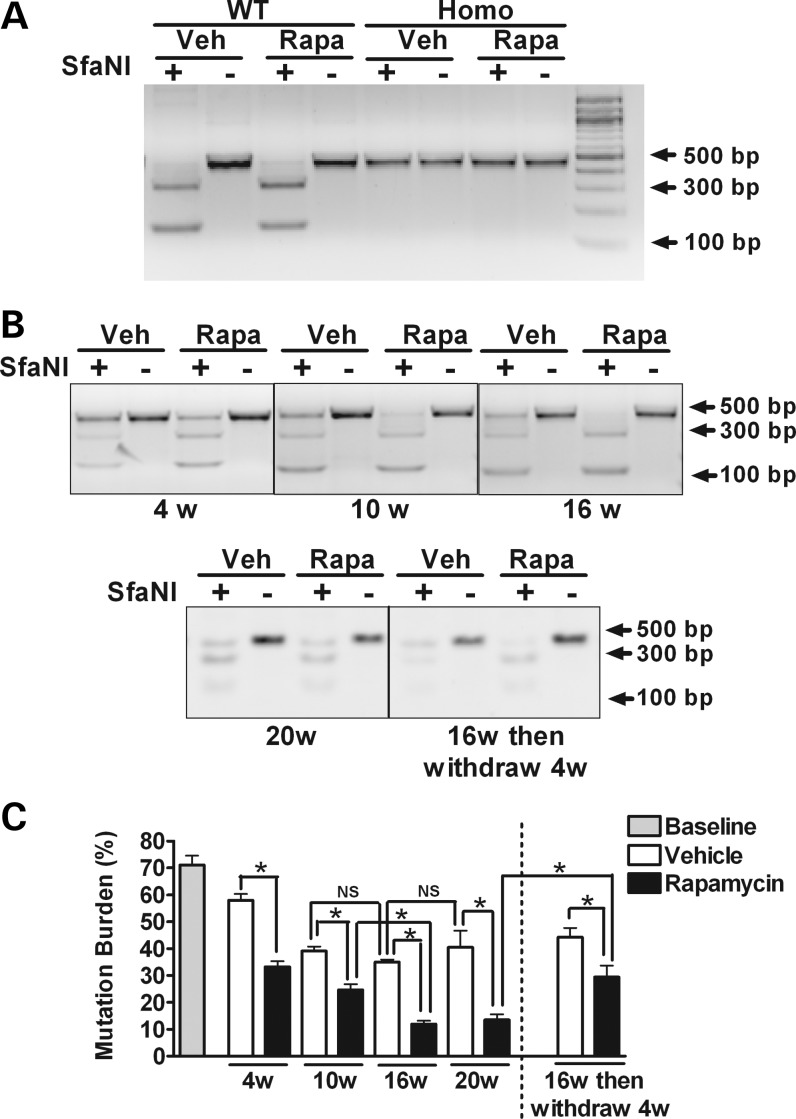

Levels of the G11778A mutation in cybrid cell lines were monitored after 1, 4, 16 and 20 weeks of culture with continuous exposure to vehicle or rapamycin. Restriction digestion analyses with SfaNI were followed by densitometric analyses of digested bands for quantification of mutation levels (Fig. 2). In cells expressing a heteroplasmic G11778A mutation, rapamycin treatment induced a significant decrease in levels of the mutation compared with vehicle-treated cells at each time point examined. The initial level of the mutation was 71% by band densitometric quantification, and this level was decreased with rapamycin treatment to ∼33, 25, 12 and 13% at 4, 10, 16 and 20 weeks, respectively (Fig. 2B and C). Interestingly, in our culture conditions, mutation levels in the vehicle-treated heteroplasmic cybrid cells also tended to drift downwards up to the 10-week time point. However, levels of the mutation were significantly lower in rapamycin-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated cells at each time point (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, levels of the mutation were not significantly different at 10 weeks compared with 16 weeks for vehicle-treated cells, whereas mutation levels continued to significantly drop over that interval in rapamycin-treated cells (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Mutation levels determined by restriction fragment-length polymorphism analysis in WT, heteroplasmic and homoplasmic cybrid cells. WT, heteroplasmic and homoplasmic cybrid cells were treated with 20 nm rapamycin or vehicle for up to 20 weeks. Restriction digestion analyses with SfaNI were followed by densitometric analysis of digested bands for quantification of mutation levels. (A) Gel images demonstrate the cleavage pattern of a 450 bp mtDNA PCR product after digestion with SfaNI. In WT cybrid cells, the mtDNA PCR product is completely cleaved at nucleotide position (np) 11778, resulting in fragments of 308 and 142 bp. In contrast, in homoplasmic G11778A cybrid cells, the mutation eliminates the cleavage site, resulting in a single 450-bp band. As expected, in WT and in homoplasmic cybrid cells, these results are not altered by 16 weeks of treatment with rapamycin compared with vehicle-treated cell. (B) The cleavage pattern of mtDNA PCR product derived from heteroplasmic cybrid cells treated with 20 nm rapamycin or vehicle for 4, 10 16 and 20 weeks. The effect of rapamycin withdrawal also was evaluated in cells that had been treated for 16 weeks with rapamycin by growing them for an additional 4 weeks in media lacking rapamycin. (C) The percentage of mtDNA with the G11778A mutation was determined by the ratio of the intensities of the 450 bp PCR product after cutting with SfaNI to the same PCR products without cutting. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, and are analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. n = 4 separately treated dishes per set of conditions. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

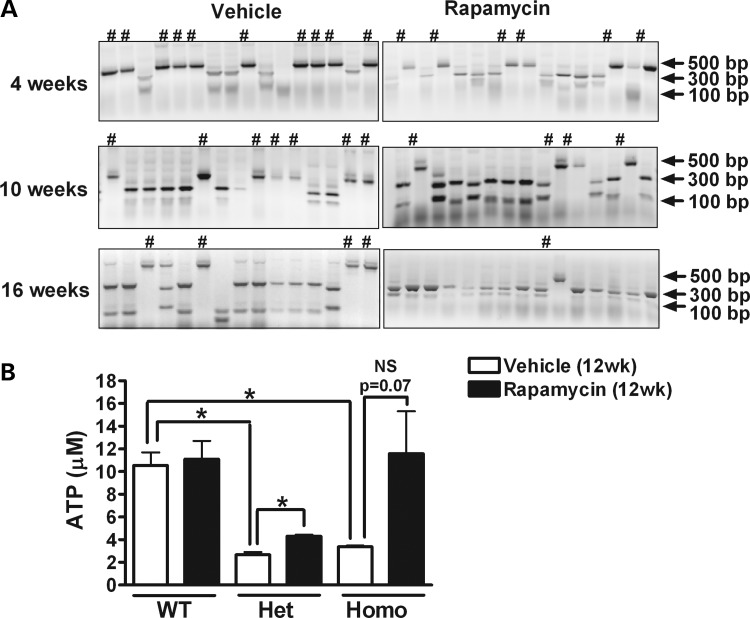

In order to determine whether mtDNA mutation levels would rebound in the absence of rapamycin, cells previously treated with rapamycin or vehicle for 16 weeks were incubated in culture media with or without rapamycin for an additional 4 weeks. The withdrawal of rapamycin resulted in a rebound of mtDNA mutation levels (from 12 to 29%), although mutation levels remained significantly lower than those in cells that had been treated with vehicle for the full 20 weeks (Fig. 2C). To further confirm the decrease in levels of the G11778A mutation, the PCR fragments were subcloned into a plasmid, 97–146 clones were randomly isolated for each set of conditions (untreated cells or those with vehicle or rapamycin treatment for 4, 10 or 16 weeks), and the cloned mtDNA molecules were amplified by a second round of PCR and digested by SfaN1 (Fig. 3A). The baseline G11778A mutation rate quantified in this manner was ∼76.5%, with 75 mutant clones out of 98 clones derived from untreated cells. In 135 clones derived from cells treated for 4 weeks with rapamycin, there were 36 clones with the G11778A mutation (26.7% mutation rate), compared with a 63.4% mutation rate in clones derived from vehicle-treated cells after 4 weeks (P < 0.0001; Table 1 and Supplementary Material, Table. S1). Although prolonged culture in vehicle for 10 and 16 weeks decreased the G11778A mutation rate to 46.4 and 33.3%, respectively, the percentages of clones harboring the mutation were remarkably lower in rapamycin-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated cells at 10 weeks (10.3%) and 16 weeks (4.5%). These mutation levels at both 10 and 16 weeks were significantly lower in the rapamycin-treated cells than vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Mutation levels determined by subcloning, and ATP measurement by luciferase assay. A total of 97–146 colonies of subcloned PCR products from untreated (A) or 4, 10 and 16 weeks vehicle- or rapamycin-treated (B) heteroplasmic cybrid cells were selected and subjected to SfaNI digestion. The percentage of cloned mtDNA molecules harboring the G11778A mutation provides an estimate of the mutational burden. # indicates clone with the G11778A mutation. (C) WT, heteroplasmic (Het) and homoplasmic (Homo) cybrid cells were treated with rapamycin or vehicle for 12 weeks and intracellular ATP concentrations were measured. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test; NS, not significant.

Table 1.

Estimate of mutation levels by subcloning

| Weeks | Treatment | WT | Mutant | Total | Mutation (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | 23 | 75 | 98 | 76.5 | N/A |

| 4 | Vehicle | 53 | 93 | 146 | 63.4 | <0.0001 |

| Rapamycin | 99 | 36 | 135 | 26.7 | ||

| 10 | Vehicle | 52 | 45 | 97 | 46.4 | <0.0001 |

| Rapamycin | 96 | 11 | 107 | 10.3 | ||

| 16 | Vehicle | 66 | 33 | 99 | 33.3 | <0.0001 |

| Rapamycin | 126 | 6 | 132 | 4.5 |

The presence or absence of the G11778A mutation was determined in 97–146 colonies for each set of conditions, including untreated cybrids and those treated with rapamycin (20 nm) or vehicle for 4, 10 and 16 weeks. Rapamycin induced a highly significant decrease in the mutational burden at all measured time points. Data were summarized from three separate experiments and analyzed by Fisher's exact test.

To determine whether the G11778A mutation caused any deficit in mitochondrial ATP production and the effects of rapamycin on ATP levels, cells were treated with rapamycin or vehicle for 12 weeks and intracellular ATP concentrations were measured by the luciferase-based assay. In the absence of rapamycin, ATP levels in heteroplasmic and homoplasmic cells carrying the G11778A mutation were significantly lower than those in WT cells. Long-term rapamycin treatment had no effect on ATP levels in WT cells but significantly increased ATP concentrations in heteroplasmic cells compared with vehicle treatment. There also was a trend toward increased ATP levels in rapamycin-treated homoplasmic cells compared with those treated with vehicle, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3B).

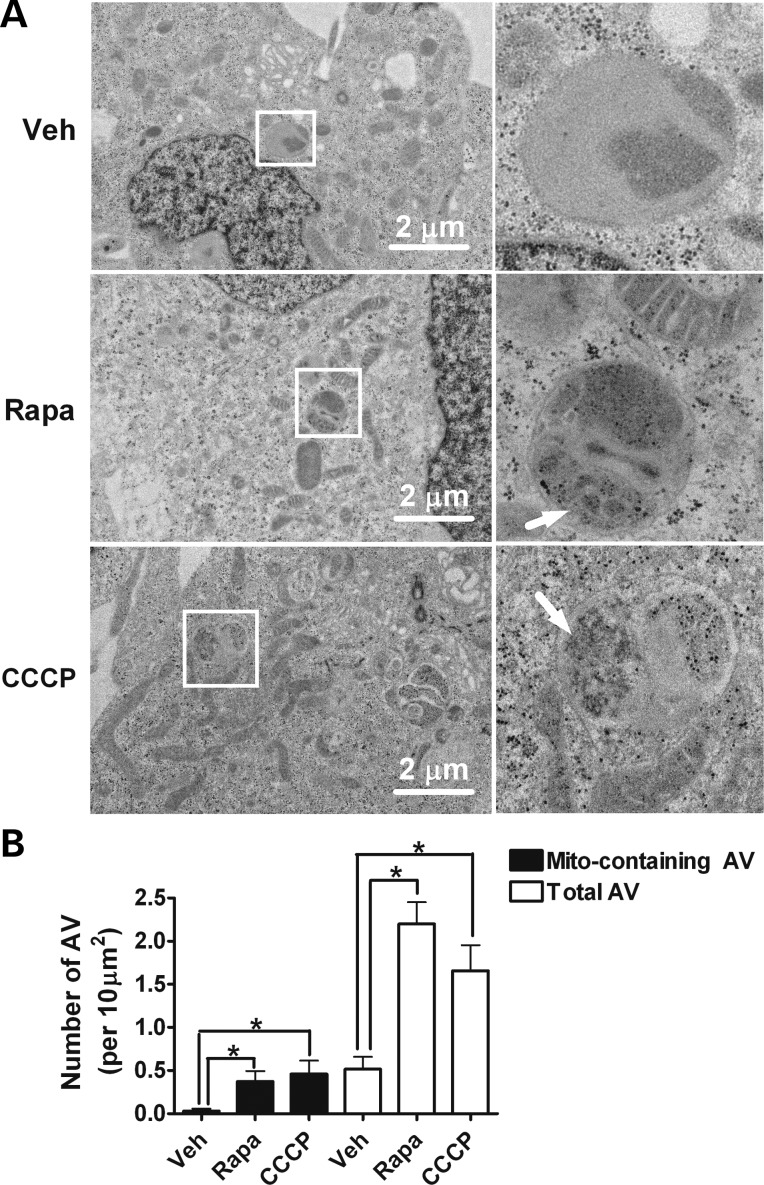

Chronic rapamycin treatment upregulated mitophagy

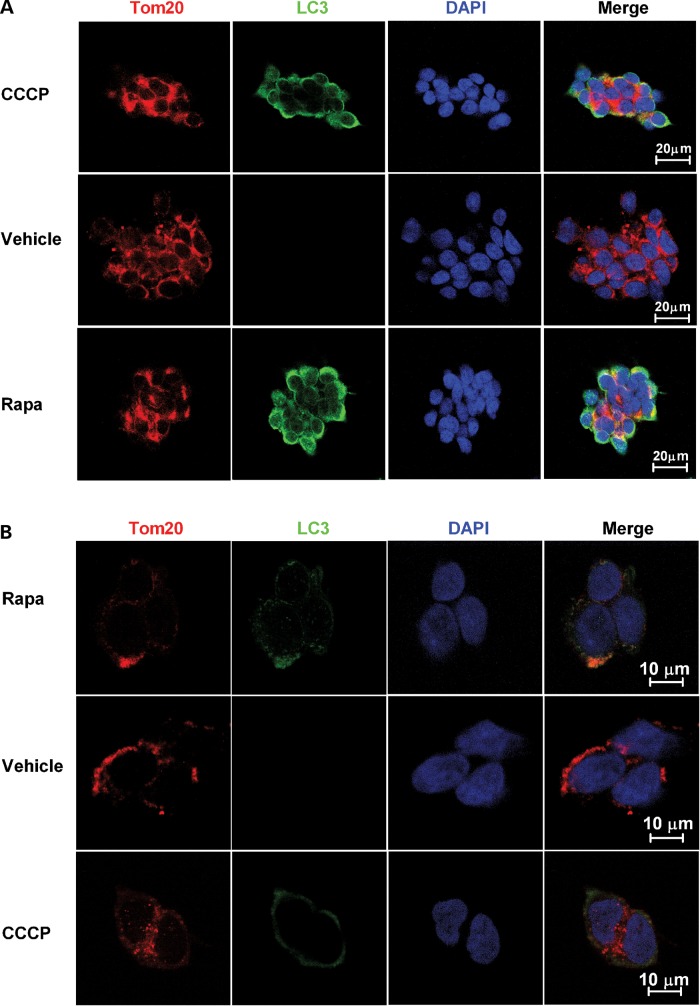

To determine whether chronic rapamycin treat upregulated mitophagy, heteroplasmic cybrid cells were treated with vehicle, 20 nm rapamycin or 20 μm CCCP for 24 h, and then subjected to immunofluorescence assay. CCCP, a potent mitochondrial uncoupling agent, should induce mitophagy and thus served as a positive control. In CCCP-treated cells, autophagy activation is observed by increased expression of the autophagosome marker, microtubule-associated light-chain 3 (LC3), which partially colocalizes with the mitochondrial marker Tom20. A similar colocalization is seen in rapamycin-treated cells, but not in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4A and B). As an additional confirmation that rapamycin increased mitophagy, electron microscopic images were analyzed for the presence of autophagic vacuoles (AVs) and mitochondria-like structures within those AVs. This analysis demonstrated a significant increase of AVs and selective mitochondrial degradation (mitophagy) in rapamycin- or CCCP-treated heteroplasmic cybrid cells (Fig. 5A and B). Vehicle-treated cells exhibited very few AVs containing mitochondrial-like profiles within AVs, whereas such profiles were significantly more frequent in rapamycin- or CCCP-treated cells. These data provide additional confirmation that rapamycin induced upregulation of mitophagy, and are consistent with our hypothesis that rapamycin-induced upregulation of mitophagy may contribute to the reduction over time in levels of the mutation.

Figure 4.

Rapamycin induces colocalization of mitochondria and autophagosomes. Heteroplasmic cybrid cells were treated with 20 nm rapamycin (Rapa), 20 μm CCCP or vehicle for 24 h, and then fixed and immunostained with anti-Tom20 antibody (red) and anti-LC3 antibody (green). The nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Confocal immunofluorescence images at low power (A) and high power (B) demonstrate that both CCCP and rapamycin induce accumulation of LC3 puncta and partial colocalization of those puncta with mitochondria as illustrated in the merged images.

Figure 5.

Rapamycin induces autophagy and mitophagy. Heteroplasmic cybrid cells were treated with 20 nm rapamycin (Rapa), 20 μm CCCP or vehicle for 24 h and examined by electron microcopy. (A) There are few AVs in vehicle-treated cells, whereas rapamycin- or CCCP-treated cells have significantly increased AVs containing mitochondria-like organelles (arrows). The right panels were enlarged from the boxed area in the left panels. (B) The number of total AVs and AVs containing mitochondria-like structure (Mito-containing AVs) were counted from 50 different cells. Data shown are mean ± SEM and are analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05.

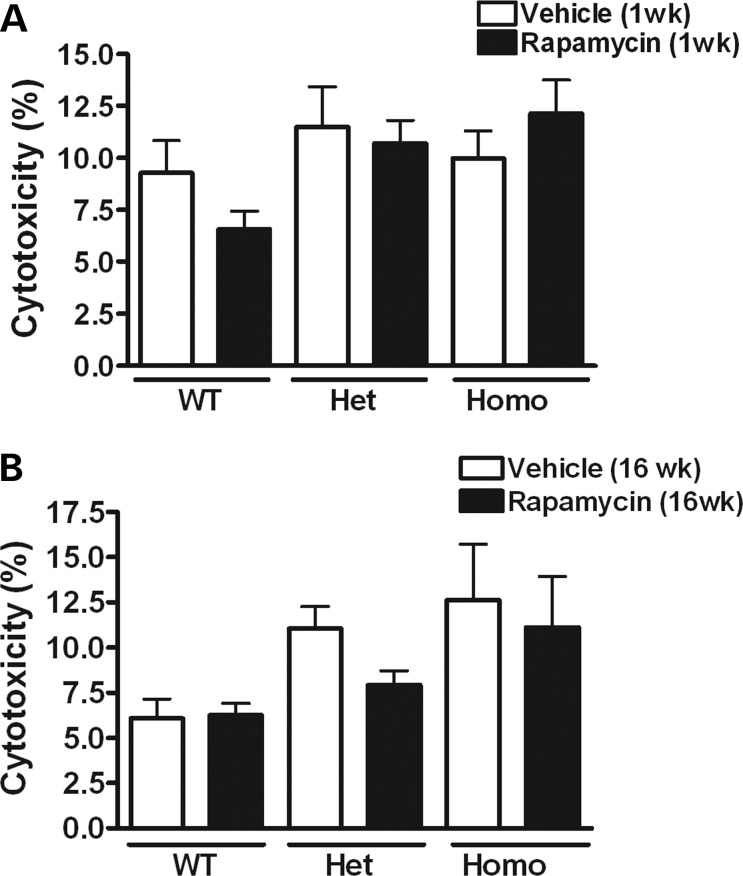

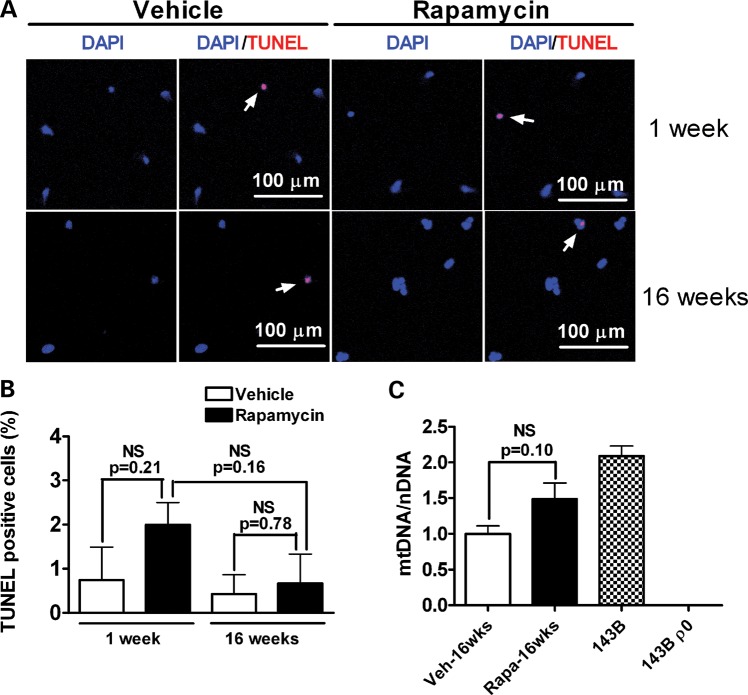

Rapamycin treatment did not affect cytotoxicity/apoptosis or mtDNA copy number

An alternative explanation for the rapamycin-induced decrease in the mtDNA mutational burden is that rapamycin-induced cell death might tend to eliminate those cells with higher mtDNA mutation levels. To test for this possibility, the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-release-based cytotoxicity assay was performed in cybrid cells with 1 and 16 weeks of vehicle or rapamycin treatment (Fig. 6A and B). There were no significant differences in cell viability between rapamycin- and vehicle-treated cells for WT, heteroplasmic or homoplasmic cybrid cells. Additionally, apoptosis was monitored by TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay in heteroplasmic cybrids treated for 1 or 16 weeks with rapamycin or vehicle. There were no significant differences in the numbers of apoptotic cells (Fig. 7A and B), indicating that the reduction in levels of the G11778A mutation by rapamycin treatment is unlikely to be due to rapamycin-induced cell death. An additional concern is that rapamycin-induced mitophagy might lead to mtDNA depletion. Therefore, the ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA (nDNA) was measured in rapamycin- and vehicle-treated heteroplasmic cybrids by quantitative real time PCR (qPCR). The mtDNA copy number in cells treated with rapamycin for 16 weeks was not significantly different from that in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 7C).

Figure 6.

Assessment of cytotoxicity in cybrid cells treated with rapamycin. LDH levels in the media before and after lysing the cells were measured and used as an index of cytotoxicity. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. There was no significant difference in cytotoxicity between rapamycin- and vehicle-treated cells after 1 week (A) or 16 weeks (B) of treatment in WT, heteroplasmic (Het) or homoplasmic (Homo) G117778A cybrid cell lines (by Student's t-test; n = 3–4 per group).

Figure 7.

Rapamycin has no effect on apoptosis or mtDNA copy number. (A) Rapamycin-induced apoptotic cell death was analyzed by TUNEL staining among vehicle or 20 nm rapamycin-treated cells after 1 and 16 weeks of treatment. Red indicates TUNEL staining and blue indicates nuclear DNA staining. The arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. (B) The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells is shown in the graph. NS, not significant by Student's t-test, n = 3–4 per group. (C) As measured by the ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA (mtDNA/nDNA), mtDNA copy number in cells treated with rapamycin for 16 weeks does not significantly differ from that in vehicle-treated cells. Total DNA from human osteosarcoma 143B cells and from cells lacking mitochondria (143B ρ0) was used as a positive and a negative control. NS, not significant by Student's t-test, n = 4 per group.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of mTOR kinase by rapamycin activates mitophagy and promotes the preferential clearance of mutant mtDNA in heteroplasmic cybrid cells carrying the LHON G11778A mutation. We found that prolonged treatment of rapamycin caused persistent inhibition of mTOR. Mitophagy was induced in cybrid cells carrying G11778A mutation, as evidenced by upregulation of the autophagosome marker LC3 and by its colocalization with the mitochondrial marker Tom20, as well as by EM evidence of a significant rapamycin-induced increase in autophagosomes as well as an increase in mitochondria-like structures within autophagosomes. Most importantly, a remarkable progressive reduction in levels of the G11778A mutation induced by rapamycin was confirmed by both restriction fragment-length polymorphism analysis of PCR products and subsequent analysis of subcloned PCR products. This reduction in mutation levels was associated with a partial restoration of ATP levels.

Maintaining a healthy population of mitochondria is critical to the well-being of cells. Mitophagy is the primary clearance mechanism for dysfunctional mitochondria, and therefore for maintaining a healthy population of mitochondria (11,12). Mitochondria undergo frequent fusion and fission events throughout the cell cycle. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential during single fusion and fission events reveals that fission may yield uneven daughter units. The daughter with a relatively decreased membrane potential has a reduced probability of undergoing subsequent fusion and is more likely to be targeted by mitophagy (20,21). The interaction of mitochondrial genetic mutations with mitophagy is largely unknown. Expressing mtDNA mutations [e.g. neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP) T8993G] causes a proportion of mitochondria to lose their membrane potential and might trigger the mitophagic process (22,23). However, it has also been reported that there is no significant difference in basal autophagy levels between cell lines containing WT or mutant mtDNA with A3243G, T8993G point mutations or large deletions (24), although widespread mitophagy can be induced in these cells by MTORC1 inhibition (18). These data suggest that the presence of a pathogenic mtDNA mutation may be insufficient on its own to induce mitophagy to a level that would drive selection against the mutation.

A number of key signaling molecules driving mitophagy have been identified in the recent years. Pioneering work has indicated that recruitment of PARKIN, a cytosolic E3 ubiquitin ligase, to mitochondria is essential for the selective elimination of impaired mitochondria in mammalian cells (15). Moreover, overexpression of PARKIN in heteroplasmic cybrid cells induces the clearance of mitochondria with a particularly severe mutation in cytochrome oxidase subunit I, thereby enriching cells with WT mtDNA and rescuing cytochrome oxidase activity (22). Two recent reports demonstrated that PARKIN translocation to the membrane of depolarized mitochondria is dependent on PTEN-induced putative kinase-1 (PINK1), which bears a mitochondrial targeting sequence, leading to the elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria through mitophagy (25,26). Further, PARKIN-mediated ubiquitination of VDAC1, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, and the recruitment of the autophagy receptor p62 have been identified as prerequisites for PINK1/PARKIN-mediated mitophagy (25). Through binding to LC3, p62 delivers mitochondria to the forming autophagosomes (25,27).

mTOR constitutes the catalytic component for two functionally distinct multiprotein complexes, mTOR complex 1 (MTORC1) and MTORC2, that coordinately act downstream of PI3K (28). Whereas MTORC1 is sensitive to the inhibitor rapamycin, MTORC2 appears to be relatively resistant to rapamycin (28,29), although recent data suggest that effects of rapamycin on insulin resistance may be mediated by MTORC2 (30). MTORC1 drives the phosphorylation of a series of downstream substrates such as the ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF-4E)-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). Phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein, a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit and a critical downstream effector of S6K1, correlates with an increase in translation of particular mRNA transcripts encoding proteins involved in cell cycle progression as well as ribosomal proteins and elongation factors necessary for translation (31,32). Thus, mTOR and its downstream effectors have being extensively studied as targets for cancer therapeutics (33). Although rapamycin and its analogs have been shown to induce cytotoxicity at higher doses (34,35), the concentration of rapamycin used in the present study (20 nm) did not cause increased cell death compared with vehicle.

The pathogenicity of the G11778A mutation in LHON patients has been clearly established (8, 36). Consistent with this, we find significant impairment of ATP production in the heteroplasmic and homoplasmic G11778A cybrids. Prolonged treatment of rapamycin reduced mutation levels and partially restored ATP levels in the heteroplasmic G11778A cybrids. However, other mechanisms in addition to the downward shift in mtDNA mutation levels may contribute to this rapamycin-induced recovery of ATP concentrations. This possibility is raised by the trend toward increased ATP levels in rapamycin-treated homoplasmic cybrids, which could not be accounted for by shifts in mutation levels. Furthermore, the impact of rapamycin on heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation levels may vary depending on the cell type and on the specific mutation. Consistent with this, recent evidence indicates that rapamycin induced mitophagy in cybrid human 143B osteosarcoma cells harboring partial deletions or complete depletion of mtDNA, but not in cybrids carrying the A3243G MELAS mutation or T8993G NARP mutation (18). Our results therefore represent the first example of the ability to drive selection against a specific mutation associated with a classic mitochondrial genetic disorder, LHON, by a pharmaceutical agent. The results, even if applicable to only a subset of mutations and cell types, remain highly significant given the complete lack of treatments proven to be effective for mitochondrial genetic disorders. In our culture conditions, percentages of the G11778A mutation declined from a baseline level of 71 to 58, 39 and 35% at 4, 10, and 16 weeks of treatment with vehicle, respectively, although mutation levels increased to 40% at week 20 and the differences between weeks 10 and 16, weeks 16 and 20 and weeks 10 and 20 were not statistically significant. These data are consistent with data from others indicating a downward drift in levels of the A3243G mutation over long periods of culture in cybrid cells (37,38), and a decrease with age in levels of a C1624T mutation in patients (39), although other data have suggested that levels of the A3243G mutation may increase with age (40). Importantly, spontaneous downward drift does not account for the results seen in rapamycin-treated cells, as rapamycin drove mutation levels significantly lower than levels in vehicle-treated cells at each time point.

Our current findings illustrate that chronic treatment with rapamycin inhibits mTOR activity, induces mitophagy and drives the progressive clearance of a pathogenic mtDNA mutation in heteroplasmic cybrid cells. The clinical impact of pathogenic heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations depends on the level of the mutation, with higher levels resulting in more severe symptoms, in part due to threshold effects (41–43). Although the G11778A mutation can be heteroplasmic or homoplasmic in LHON patients, pathogenic tRNA mutations such as the A3243G MELAS mutation are always heteroplasmic (44,45). However, it is possible that the strategy shown to be effective here for driving down levels of the G11778A mutation may be effective only for a subset of mutations and cell types. These data suggest that driving mutation levels lower by treatment with rapamycin or other mitophagy enhancers should be further studied as a potential therapeutic strategy for mitochondrial disorders associated with heteroplasmic mtDNA mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

Cybrids were created as previously reported (46,47) by fusing platelets from members of a family with an atypical phenotype of maternally inherited parkinsonism, dystonia and dementia without optic atrophy, associated with the G11778A mtDNA mutation (48) to SH-SY5Y ρ0 cells, which are cells that had been chronically treated with ethidium bromide to remove mtDNA. Control cybrids were prepared using platelets from spouses or paternal relatives of the same family. The ρ0 cells require supplemental uridine and pyruvate to survive, and therefore selection by removal of these supplements promoted survival only of cells with mtDNA repopulation. Identification of the G11778A mutation was performed by sequencing as previously reported (48). Three different cell lines were grown in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Their initial G11778A mutation proportions were 0, ∼75 and 100%, termed WT, heteroplasmic and homoplasmic cybrid cells hereafter. Equal numbers of cells were plated at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per 75 cm2 tissue culture flask. Every 7 days when cells reached 80% confluence, they were trypsinized and re-seeded into a new flask. There were no differences in the rate of growth based on the degree of confluence at the time of splitting, or the total number of cells per flask when counted using a hemocytometer [vehicle versus rapamycin, (15.1 ± 1.8) × 106 versus (12.2 ± 1.6) × 106, P = 0.27] after 16 weeks of treatment.

Drugs

Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as 1 mm stock solution. Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorop-henylhydrazone (CCCP, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO as 100 mm stock solution. All compounds were further diluted (at least 1:5000) in cell culture media before they were applied to the cells and washed out before lysing the cells.

Western blot

Cells were harvested and lysed using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1:200 Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 3 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein concentration was determined and quantitative western analysis was performed as previously described (49). Proteins were separated on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and then electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were then incubated in blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk, 0.1% Tween 20, and 1× TBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody on a shaker. Primary antibodies (Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein (Ser240/244) Antibody, 1:1000; S6 Ribosomal Protein Antibody, 1:2000, both from Cell Signaling Technology) were diluted in antibody buffer (1% non-fat dry milk, 0.1% Tween 20 and 1× TBS). The next day, membranes were washed with TBS/0.1% Tween 20, and then incubated with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz) diluted 1: 2000 in antibody buffer. Membranes were washed, and signal was detected using LumiGOLD ECL western blotting detection kit (SignaGen). Using ImageJ for Windows, immunoblots were quantified by calculating the integrated optical density of each protein band on the film.

MtDNA mutation burden

Levels of the G11778A mutation were detected by PCR amplification followed by restriction endonuclease analysis as previously described (48). PCR amplification was performed with primers at nucleotide position (np) 5′–3′ 11 479–11 498 (upper) and 11 929–11 910 (lower). Restriction digests were performed with SfaNI (New England Biolabs) and analyzed by ultraviolet illumination of a 2.5% agarose gel. The mutation eliminated the single restriction site for this enzyme. Band intensities were assessed using ImageJ for Windows. Background intensities were measured by a region of the gel lacking a band adjacent to the bands at 450 bp. After background subtraction, the intensity ratio of bands at 450 bp cut with SfaNI and those without cutting was used as an estimation of the mutational burden. In order to further confirm the mutation level, the PCR product was subcloned using PCR and TOPO cloning (TOPO TA Cloning kit, Invitrogen) and then mtDNA from individual clones was PCR amplified and subjected to restriction digestion by SfaN1. The percentage of clones harboring the mutation provided an estimate of the mutational burden.

ATP measurement

ATP was measured using the ATP-determination kit (Molecular Probes) according to the directions of the manufacturer. Cultured cells were collected and immediately placed in ice-cold passive lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min and the supernatant was measured for protein concentration. A 10 µl sample (containing 5 µg protein) or 10 µl ATP standard solution was added to 90 µl of reaction buffer in each well of a 96-well plate. Luminescence was measured using a PerkinElmer Victor3 Luminometer. All experiments were run in triplicate, and the background luminescence was subtracted from the measurement. ATP concentrations in experimental samples were calculated from the ATP standard curve.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were plated on sterile glass cover slips in eight-well tissue culture dishes. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS pH 7.4, and then fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 min. After fixation, cells were washed in PBS and incubated in 1–3% (w/v) BSA and 10% (v/v) normal goat serum (NGS) for 30 min to block non-specific binding. Cells were then incubated overnight with primary antibody: (i) Tom20 (Santa Cruz) mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:50 dilution; (ii) LC3B (Novus Biologicals) rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:100 dilution in 1% NGS + 1× PBS. Next, cells were washed and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody: goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 555 and Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 488 at 1:1000 dilution (Invitrogen). Next, cover slips were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and sealed with clear nail polish. As a control for non-specific labeling with secondary antibody, omission of the primary antibody was also performed on a slide from each case. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed using a protocol previously described (50). Cells were fixed for 2 h with 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer pH 7.4. They were then washed three times in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer for 10 min and then post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide + 0.03 g/4 ml potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h. After dehydration in increasing concentrations of ethanol, 10 min for each step: 30, 50, 70 95 and 100%, infiltration proceeded overnight with 1:1 ethanol and LX112 Epon resin. Eighty nanometer sections were obtained using a Leica Ultracut E ultramicrotome, and contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate for 10 min and lead citrate for 5 min. Observations were performed on a JEOL 1400 TEM equipped with a side mount Gatan Orius SC1000 digital camera. For our analysis, AVs include autophagosomes, which are double membrane structures containing undigested cytoplasmic material such as mitochondria and ribosomes, and autolysosomes, which are single membrane structures with densely compacted amorphous or multilamellar contents (51). AVs and mitochondria engulfed within AVs were identified as previously described (52). For quantification of AVs per 10 µm2 of cytoplasm, the numbers of total AVs larger than 0.5 μm in diameter and mitochondria-containing AVs were scored in the microscopic field (10 × 7 µm) in 50 cells (1 field/cell). This analysis was conducted in a blinded manner and data were presented as means ± SE.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells treated with rapamycin or vehicle for 1 and 16 weeks were seeded in a 96-well culture plate (30 000cells/well) in 200 μl of culture medium. After 48 h of additional treatment, LDH assays were performed on the cells using the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the plate was centrifuged at 250g at 4C for 5 min, and then 50 μl medium supernatant was removed and placed in another 96-well plate. The cells were frozen in the remaining media at −80°C followed by thawing in order to lyse the cells. The cells and media were centrifuged again and 50 μl of the supernatant was removed and placed in the remaining wells of the new 96-well plate. Fifty microliters of substrate solution was added to all samples and the plate was incubated at room temperature in the dark. After 30 min of incubation, 50 μl of stop solution was added to each well and the absorbance was recorded at 490 nm. Percent cytotoxicity was determined by the ratio of LDH activity in the media before lysing the cells to that in the media collected before and after the cells were lysed.

TUNEL assay

TUNEL staining to detect apoptosis was performed using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocol. TUNEL reaction was labeled with TMR red and the nuclear DNA was labeled with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were analyzed by confocal microscopy with appropriate filters (LSM510, Carl Zeiss). The number of TUNEL-positive and total cells in randomly selected fields from 3 to 4 slides (10 fields/slide) in each experimental group was counted using a 20× objective.

Measurement of mtDNA copy number

For quantification of mtDNA copy number, real-time DNA PCR analysis was performed with the NovaQUANT™ Human Mitochondrial to Nuclear DNA Ratio Kit (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA extractions were performed on frozen cells using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen). A set of four optimized PCR primer pairs targeting two mitochondrial genes (ND1 and ND6) and two nuclear genes (BECN1 and NEB) were pre-aliquoted in an Applied Biosystems MicroAmp® Fast Optical 96-well Reaction Plate. A fast real-time qPCR system (Applied Biosystems 7900HT) was used to measure the ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA, representing the relative mtDNA copy number, which in turn reflects the mtDNA content per cell. Total DNA from human osteosarcoma 143B cells and from cells lacking mtDNA (143B ρ0) was used as a positive and a negative control.

Statistical analyses

Mutation frequencies among colonies in the table were compared by a two-tailed Fisher's exact test. mTOR inhibition and cytotoxicity data were analyzed by a two-tailed student's t-test. mtDNA mutation levels were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test. GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all statistical tests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R21NS077758 to D.K.S.); and the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation (UMDF11-095 to Y.D.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Susan J. Hagen and Andrea Calhoun (Imaging Core at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) for their assistance with electron microscopy imaging and analysis.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiMauro S., Schon E.A. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;31:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094302. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace D.C. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2010;51:440–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace D.C. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace D.C. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:685–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc3365. doi:10.1038/nrc3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kujoth G.C., Hiona A., Pugh T.D., Someya S., Panzer K., Wohlgemuth S.E., Hofer T., Seo A.Y., Sullivan R., Jobling W.A., et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. doi:10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trifunovic A., Wredenberg A., Falkenberg M., Spelbrink J.N., Rovio A.T., Bruder C.E., Bohlooly Y.M., Gidlof S., Oldfors A., Wibom R., et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. doi:10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman N.J. From genotype to phenotype in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: still more questions than answers. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22:257–261. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200212000-00001. doi:10.1097/00041327-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace D.C., Singh G., Lott M.T., Hodge J.A., Schurr T.G., Lezza A.M., Elsas L.J., 2nd, Nikoskelainen E.K. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Science. 1988;242:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.3201231. doi:10.1126/science.3201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh G., Lott M.T., Wallace D.C. A mitochondrial DNA mutation as a cause of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;320:1300–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905183202002. doi:10.1056/NEJM198905183202002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adhya S., Mahato B., Jash S., Koley S., Dhar G., Chowdhury T. Mitochondrial gene therapy: the tortuous path from bench to bedside. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman S.J., Taylor R., Zhang Y., Jin S. Autophagy and the degradation of mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.01.005. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemasters J.J. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2005;8:3–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.3. doi:10.1089/rej.2005.8.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan T., Rawal P., Wu Y., Xie W., Jankovic J., Le W. Rapamycin protects against rotenone-induced apoptosis through autophagy induction. Neuroscience. 2009;164:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.014. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandoval H., Thiagarajan P., Dasgupta S.K., Schumacher A., Prchal J.T., Chen M., Wang J. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008;454:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. doi:10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narendra D., Tanaka A., Suen D.F., Youle R.J. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. doi:10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komatsu M., Waguri S., Ueno T., Iwata J., Murata S., Tanida I., Ezaki J., Mizushima N., Ohsumi Y., Uchiyama Y., et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. doi:10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee I.H., Cao L., Mostoslavsky R., Lombard D.B., Liu J., Bruns N.E., Tsokos M., Alt F.W., Finkel T. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilkerson R.W., De Vries R.L., Lebot P., Wikstrom J.D., Torgyekes E., Shirihai O.S., Przedborski S., Schon E.A. Mitochondrial autophagy in cells with mtDNA mutations results from synergistic loss of transmembrane potential and mTORC1 inhibition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:978–990. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr529. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahalati K., Kahan B.D. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sirolimus. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:573–585. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140080-00002. doi:10.2165/00003088-200140080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twig G., Elorza A., Molina A.J., Mohamed H., Wikstrom J.D., Walzer G., Stiles L., Haigh S.E., Katz S., Las G., et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim I., Rodriguez-Enriquez S., Lemasters J.J. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;462:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.034. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suen D.F., Narendra D.P., Tanaka A., Manfredi G., Youle R.J. Parkin overexpression selects against a deleterious mtDNA mutation in heteroplasmic cybrid cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11835–11840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914569107. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914569107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M., Borgeld H.J., Zhang J., Muramatsu S., Gong J.S., Yoneda M., Maruyama W., Naoi M., Ibi T., Sahashi K., et al. Gene therapy for mitochondrial disease by delivering restriction endonuclease SmaI into mitochondria. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002;9:534–541. doi: 10.1159/000064726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Vries R.L., Gilkerson R.W., Przedborski S., Schon E.A. Mitophagy in cells with mtDNA mutations: being sick is not enough. Autophagy. 2012;8:699–700. doi: 10.4161/auto.19470. doi:10.4161/auto.19470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisler S., Holmstrom K.M., Skujat D., Fiesel F.C., Rothfuss O.C., Kahle P.J., Springer W. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. doi:10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vives-Bauza C., Zhou C., Huang Y., Cui M., de Vries R.L., Kim J., May J., Tocilescu M.A., Liu W., Ko H.S., et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraft C., Peter M., Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. doi:10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guertin D.A., Sabatini D.M. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M., Sengupta S., Sheen J.H., Hsu P.P., Bagley A.F., Markhard A.L., Sabatini D.M. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamming D.W., Ye L., Katajisto P., Goncalves M.D., Saitoh M., Stevens D.M., Davis J.G., Salmon A.B., Richardson A., Ahima R.S., et al. Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science. 2012;335:1638–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1215135. doi:10.1126/science.1215135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson R.T., Schreiber S.L. Translation control: connecting mitogens and the ribosome. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:R248–R250. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70152-6. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jefferies H.B., Fumagalli S., Dennis P.B., Reinhard C., Pearson R.B., Thomas G. Rapamycin suppresses 5′TOP mRNA translation through inhibition of p70s6k. EMBO J. 1997;16:3693–3704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3693. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.12.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang S., Houghton P.J. Targeting mTOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003;3:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. doi:10.1016/S1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geoerger B., Kerr K., Tang C.B., Fung K.M., Powell B., Sutton L.N., Phillips P.C., Janss A.J. Antitumor activity of the rapamycin analog CCI-779 in human primitive neuroectodermal tumor/medulloblastoma models as single agent and in combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1527–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyler B., Wadsworth S., Recinos V., Mehta V., Vellimana A., Li K., Rosenblatt J., Do H., Gallia G.L., Siu I.M., et al. Local delivery of rapamycin: a toxicity and efficacy study in an experimental malignant glioma model in rats. Neurol. Oncol. 2011;13:700–709. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor050. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nor050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman N.J. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. New genetic considerations. Arch. Neurol. 1993;50:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540050082021. doi:10.1001/archneur.1993.00540050082021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakker A., Barthelemy C., Frachon P., Chateau D., Sternberg D., Mazat J.P., Lombes A. Functional mitochondrial heterogeneity in heteroplasmic cells carrying the mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with the MELAS syndrome (mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) Pediatr. Res. 2000;48:143–150. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200008000-00005. doi:10.1203/00006450-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yano T., Tanaka M., Fukuda N., Ueda T., Nagase H. Loss of mutant mitochondrial DNA harboring the MELAS A3243G mutation in human cybrid cells after cell-cell fusion with normal tissue-derived fibroblast cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010;25:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sangatsuda Y., Nakamura M., Tomiyasu A., Deguchi A., Toyota Y., Goto Y., Nishino I., Ueno S., Sano A. Heteroplasmic m.1624C>T mutation of the mitochondrial tRNA(Val) gene in a proband and his mother with repeated consciousness disturbances. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.10.002. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C., Liu V.W., Addessi C.L., Sheffield D.A., Linnane A.W., Nagley P. Differential occurrence of mutations in mitochondrial DNA of human skeletal muscle during aging. Hum. Mutat. 1998;11:360–371. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:5<360::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-U. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:5<360::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiMauro S., Moraes C.T. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Arch. Neurol. 1993;50:1197–1208. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540110075008. doi:10.1001/archneur.1993.00540110075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossignol R., Malgat M., Mazat J.P., Letellier T. Threshold effect and tissue specificity. Implication for mitochondrial cytopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33426–33432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33426. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.47.33426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boulet L., Karpati G., Shoubridge E.A. Distribution and threshold expression of the tRNA(Lys) mutation in skeletal muscle of patients with myoclonic epilepsy and ragged-red fibers (MERRF) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:1187–1200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon D.K., Johns D.R. Mitochondrial disorders: clinical and genetic features. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999;50:111–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.111. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howell N., Elson J.L., Chinnery P.F., Turnbull D.M. mtDNA mutations and common neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Genet. 2005;21:583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.012. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swerdlow R.H., Parks J.K., Miller S.W., Tuttle J.B., Trimmer P.A., Sheehan J.P., Bennett J.P., Jr, Davis R.E., Parker W.D., Jr Origin and functional consequences of the complex I defect in Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:663–671. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400417. doi:10.1002/ana.410400417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King M.P., Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science. 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. doi:10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon D.K., Pulst S.M., Sutton J.P., Browne S.E., Beal M.F., Johns D.R. Familial multisystem degeneration with parkinsonism associated with the 11778 mitochondrial DNA mutation. Neurology. 1999;53:1787–1793. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1787. doi:10.1212/WNL.53.8.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dai Y., Kiselak T., Clark J., Clore E., Zheng K., Cheng A., Kujoth G.C., Prolla T.A., Maratos-Flier E., Simon D.K. Behavioral and metabolic characterization of heterozygous and homozygous POLG mutator mice. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tashima K., Zhang S., Ragasa R., Nakamura E., Seo J.H., Muvaffak A., Hagen S.J. Hepatocyte growth factor regulates the development of highly pure cultured chief cells from rat stomach by stimulating chief cell proliferation in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G319–G329. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90355.2008. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.90355.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boland B., Kumar A., Lee S., Platt F.M., Wegiel J., Yu W.H., Nixon R.A. Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6926–6937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu C.T. A pivotal role for PINK1 and autophagy in mitochondrial quality control: implications for Parkinson disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:R28–R37. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq143. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.