Abstract

Purpose

To quantify the prevalence of prescribed opioid analgesics among pregnant women enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid from 1995 to 2009.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of 277,555 pregnancies identified from birth and fetal death certificates, and linked to previously-validated computerized pharmacy records. Poisson regression was used to estimate trends over time, rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

During the study period, 29% of pregnant women filled a prescription for an opioid analgesic. From 1995 to 2009, any pregnancy-related use increased 1.90-fold (95% CI = 1.83, 1.98), first trimester use increased 2.27-fold (95% CI = 2.14, 2.41), and second or third trimester use increased 2.02-fold (95% CI = 1.93, 2.12), after adjusting for maternal characteristics. Any pregnancy-related, first trimester, and second or third trimester use were each more likely among mothers who were at least 21 years old, white, non-Hispanic, prima gravid, resided in non-urban areas, enrolled in Medicaid due to disability, and who had less than a high school education.

Conclusions

Opioid analgesic use by Tennessee Medicaid-insured pregnant women increased nearly 2-fold from 1995 to 2009. Additional study is warranted in order to understand the implications of this increased use.

MeSH KEYWORDS: Opioids, Pregnancy, Prescription

INTRODUCTION

Providers and pregnant women often face difficult choices identifying safe and effective medications to use when treating maternal conditions during pregnancy. This is particularly true for commonly used drugs such as opioids [1–15]. Existing guidelines do not recommend avoiding opioids during pregnancy [16–19], but emerging data suggest that the risks of exposure to the developing fetus may warrant reexamination of current recommendations [20–33].

Ex vivo and animal studies suggest a possibility of teratogenic effects with early fetal exposure to some opioid analgesics [20–26]. A recent case control study using birth defect registry data demonstrated that early fetal exposure to prescription opioid analgesics was associated with 1.8- to 2.7-fold increased risk for specific cardiovascular and central nervous system defects [27]. The risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome with later fetal exposure is well-documented [28–33]; evidence suggests that approximately half of all babies with later fetal opioid exposure are likely to develop some signs of neonatal abstinence syndrome. [26, 34]

Little is known about the magnitude of fetal exposure to prescription opioid analgesics [28–35]. Given the potential risks of both early and later fetal opioid exposure, it is important to quantify the magnitude of exposure to these powerful medications. Thus, we conducted a large, retrospective cohort study to describe changing use of prescription opioid analgesics by women enrolled in Tennessee’s Medicaid program during pregnancy from 1995 to 2009.

METHOD

Data Sources

The study was conducted using the Tennessee Medicaid Research database which includes birth, death and fetal death certificates linked to Tennessee Medicaid administrative claims and U.S. census data. Birth, death and fetal death certificates were used to identify mothers with a live birth or fetal death in Tennessee from 1995 to 2009. The date of conception was defined in one of two ways. For those births in which the date of the last menstrual period (LMP) was recorded on the birth certificate, the date of conception was defined as the LMP date [36, 37]. For those births in which the LMP date was not recorded on the birth certificate (approximately 10%), a previously-validated method of estimating the LMP was used [36–38]. Birth and fetal death certificates were also used to define the date of delivery or fetal death and maternal age (less than 21 years vs. 21 years or more), race (white vs. black vs. other), ethnicity (non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic), education level (less than high school vs. high school or more), and number of prior pregnancies (none vs. one or more).

Tennessee Medicaid data were used to identify the reason for Medicaid enrollment (not disabled vs. disabled) and filled prescriptions for opioid analgesics. Studies among non-pregnant populations demonstrate that administrative pharmacy claims data are free of recall bias and are highly concordant with patient reported medication use [38–41], although concordance may differ for pregnant populations. Medicaid pharmacy data included information about the date a prescription was filled and the number of days of medication supply for all outpatient prescriptions paid for by the Tennessee Medicaid program. All study pregnancies were classified according to opioid analgesic use during pregnancy including prescriptions for opioid agonist medications (codeine, dihydrocodeine combinations, dezocine, fentanyl, hydrocodone combinations, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine hydrochloride, meperidine promethazine, methodone hydrochloride, morphine sulfate, oxycodone combinations, oxymorphone hydrochloride, propoxyphene and propoxyphene combinations, sufentanil citrate, and tramadol hydrochloride), mixed opioid agonist and antagonist medications (buprenorphine, butorphanol tartrate, nalbuphine hydrochloride, and pentazocine hydrochloride), opioid and barbiturate combinations (codeine butalbital, oxycodone and barbituates), and narcotic and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (non-acetylsalicylic acid) combinations (hydrocodone ibuprofen). Cough preparations were excluded by identifying combinations with cough and cold medicines and reviewing trade names. For women with evidence of first trimester opioid use, filled prescriptions for other medications and ICD codes associated with medical claims paid within 30 days before and 7 days after the first qualifying opioid prescription were classified into four mutually exclusive, hierarchical diagnoses categories (e.g., cancer, opioid abuse or dependence, non-cancer pain, or other diagnoses).

U.S. Census data were used to define residence at time of delivery as in a rural, suburban or urban standard metropolitan statistical area. Permission to perform the study was obtained from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, the State of Tennessee Health Department, and the TennCare Bureau (e.g., the Tennessee Medicaid program).

Cohort Construction

Pregnancies were included in the cohort if the date of delivery or fetal death was between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2009, the mother was listed as a Tennessee resident on the birth certificate, and the mother was enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program from 30 days prior to the LMP date through the date of delivery or fetal death, allowing for gaps in enrollment less than 30 days. The final cohort included 277,555 pregnancies. The number of mothers enrolled in the cohort increased from 14,448 in 1995 to 17,434 in 2009 (Table 1), which reflects nationwide Medicaid expansions over time [42].

Table 1.

Number of pregnancies and pregnancy characteristics, 1995–2009

| Year | Number of pregnancies | % < 21 yrs old | % Black race | % Urban residence | % Enrolled disabled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years | 277,555 | 41.9 | 42.1 | 45.9 | 8.1 |

| 1995 | 14,448 | 45.7 | 47.6 | 52.1 | 8.1 |

| 1996 | 17,346 | 44.7 | 43.7 | 49.7 | 7.3 |

| 1997 | 17,090 | 44.1 | 43.7 | 48.6 | 7.6 |

| 1998 | 18,602 | 43.6 | 43.0 | 47.5 | 8.0 |

| 1999 | 19,421 | 42.2 | 41.2 | 46.1 | 7.7 |

| 2000 | 20,146 | 42.6 | 41.1 | 45.5 | 7.7 |

| 2001 | 20,839 | 41.3 | 39.8 | 44.7 | 7.4 |

| 2002 | 20,821 | 41.0 | 38.8 | 44.0 | 7.4 |

| 2003 | 18,308 | 41.1 | 39.8 | 43.5 | 8.9 |

| 2004 | 17,728 | 39.5 | 40.5 | 44.3 | 9.2 |

| 2005 | 18,367 | 39.1 | 41.1 | 44.3 | 9.0 |

| 2006 | 19,197 | 40.7 | 42.3 | 45.0 | 8.0 |

| 2007 | 19,100 | 41.2 | 43.6 | 45.0 | 8.1 |

| 2008 | 18,708 | 41.1 | 44.1 | 45.2 | 8.8 |

| 2009 | 17,434 | 42.2 | 43.9 | 45.3 | 8.5 |

A fetus was considered to have first trimester exposure if the mother filled a prescription between the date of the LMP and the date of LMP plus 90 days, or if a prescription was filled in the 30 days before the LMP with at least one days’ supply extending past the LMP date into the first trimester. At least 1 day of exposure was also necessary for second and third trimester exposure, with the exception that possible delivery-related prescriptions (e.g., those filled within 3 days before the date of delivery or fetal death) were excluded.

Analysis Plan

Study outcomes were any pregnancy-related exposure to an opioid analgesic, first trimester exposure to an opioid analgesic with or without exposure later in pregnancy, and second or third trimester exposure to an opioid analgesic with or without exposure in the first trimester. Poisson regression was used to estimate trends over time, adjusted rate ratios (aRR), and 95% confidence intervals (95% C.I.) adjusting for maternal covariates. Year of delivery or fetal death was defined as a categorical variable, except in analyses to test for linear trend. From the regression models, marginal prediction was used to compute rates for each calendar year, again adjusting for maternal covariates [43]. For first trimester use, Poisson regression models were also built to estimate aRR and 95% CI in 2009 compared to 1995 for the four most commonly used individual opioid medications and all other opioid medications. To account for autocorrelation due to mothers with more than one pregnancy during the study period, the robust Huber-White sandwich variance estimator was used to provide correct standard errors and confidence intervals of the estimated rate ratios [44]. To guard against the possibility that results are due to cough preparations even after the removal of individual medications that were likely to be cough preparations, a sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding all codeines and trends remained statistically significant (data not shown). Analyses are complete case analyses and were performed with R version 2.15.1 [45].

RESULTS

Cohort Description

Of the 277,555 pregnant women included in the cohort, 80,608 (29.0%) filled a prescription for an opioid analgesic with at least 1 day supply at any time during pregnancy. Early fetal exposure occurred in 40,305 (14.5%) and later fetal exposure occurred in 59,127 (21.3%) of pregnancies. The median opioid analgesic supply was 4 days in the first trimester (range = 1–91 days; IQR = 2–10) and in the second or third trimester (range 1–115 days; IQR = 2–9). Characteristics of opioid-exposed and unexposed pregnancies are shown in Table 2. In comparison to non-users, users were more likely to be 21 years of age or older, white, prima gravid, residing in a non-urban area and enrolled in Medicaid due to disability.

Table 2.

Characteristics of women that did and did not use any opioid analgesic during pregnancy, 1995–2009

| Variable | Total Cohort (n = 277,555) | Non User (n = 196,947) | User (n = 80,608) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Age < 21 yrs | 41.9 | 43.9 | 37.1 |

| % Black | 42.1 | 45.8 | 33.2 |

| % Hispanic | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| % Non prima gravid | 25.0 | 27.1 | 19.9 |

| % Urban | 45.9 | 48.6 | 39.3 |

| % Disabled | 8.1 | 7.7 | 9.0 |

Changes in Opioid Analgesic Use

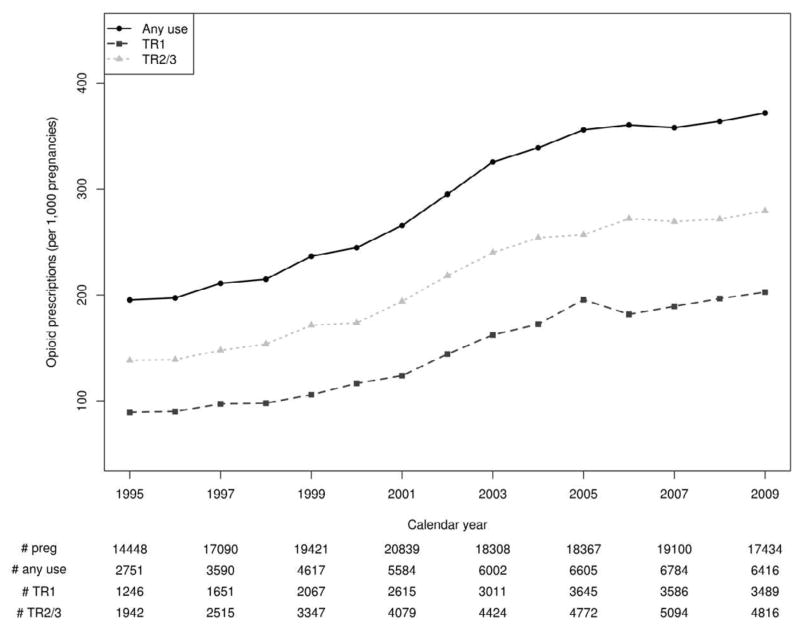

Figure 1 shows the adjusted prevalence of any pregnancy-related use of an opioid analgesic, first trimester use, and second or third trimester use. Linear tests for trend were significant for any pregnancy-related use (β = 0.052; 95% CI = 0.051, 0.053), first trimester use (β = 0.067; 95% CI = 0.065, 0.069), and second or third trimester use (β = 0.057; 95% CI = 0.055, 0.059).

Figure 1.

Opioid analgesic use during pregnancy: Tennessee Medicaid, 1995–2009

TR1 = First trimester use (with or without second or third trimester use); TR2/3 = Second or third trimester use (with or without first trimester use)

Table 3 shows results of the multivariate regression models for any pregnancy-related, first-trimester, and second- or third-trimester opioid analgesic use. Compared to opioid use in 1995, any pregnancy-related (aRR = 1.90; 95% CI = 1.83, 1.98), first trimester (aRR = 2.27; 95% CI = 2.14, 2.41), and second or third trimester (aRR = 2.02; 95% CI = 1.93, 2.12) opioid analgesic use increased significantly by 2009 after adjusting for maternal covariates. Any pregnancy-related use, first trimester use, and second or third trimester use were each more likely among mothers who were 21 years or older, white, non-Hispanic, and prima gravid with less than a high school education who were residing in a non-urban area and enrolled in Medicaid due to disability.

Table 3.

Adjusted rate ratio (aRR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for prescribing of opioid analgesics during pregnancy: Tennessee Medicaid, 1995–2009.

| Any Use | First Trimester Use | Second or Third Trimester Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | aRR | 95% CI | aRR | 95% CI | aRR | 95% CI |

| 1995 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2009 | 1.90 | 1.83, 1.98 | 2.27 | 2.14, 2.41 | 2.02 | 1.93, 2.12 |

| Age less than 21 years | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Age 21 years or more | 1.11 | 1.09, 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.16, 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.11, 1.15 |

| White race | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Black | 0.69 | 0.68, 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.59, 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.65, 0.67 |

| Other | 0.62 | 0.58, 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.56, 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.55, 0.66 |

| Non-Hispanic | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Hispanic | 0.66 | 0.63, 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.58, 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.55, 0.66 |

| Less than 12 years | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 12 years or more | 0.95 | 0.93, 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.90, 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 |

| Not prima gravid | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Prima gravid | 1.30 | 1.28, 1.32 | 1.18 | 1.15, 1.22 | 1.08 | 1.06, 1.10 |

| Urban residence | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Suburban residence | 1.11 | 1.09, 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.15, 1.22 | 1.08 | 1.06, 1.10 |

| Rural residence | 1.04 | 1.02, 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.09, 1.15 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| Not disabled | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Disabled | 1.14 | 1.11, 1.16 | 1.29 | 1.25, 1.33 | 1.13 | 1.10, 1.16 |

First Trimester Exposures

From 1995 to 2009, the proportion of women prescribed an opioid analgesic during the first trimester with evidence of opioid abuse or dependence diagnoses increased from 0.18 to 0.63% (249.26% increase) and with evidence of non-cancer pain diagnoses increased from 53.57 to 71.73% (33.90% increase), while the proportion of women prescribed an opioid analgesic during the first trimester with evidence of a cancer diagnosis decreased from 0.63 to 0.42% (33.47% decrease) and with evidence of other diagnoses decreased from 45.61 to 27.21% (40.34% decrease).

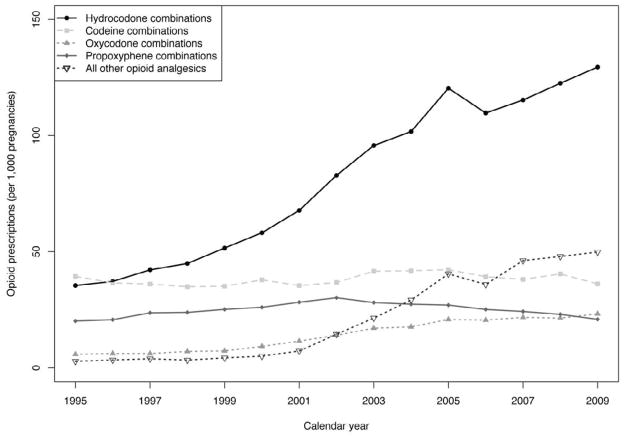

Figure 2 shows the adjusted prevalence of first trimester opioid analgesic use by individual medication for the four most commonly used individual opioid medications (hydrocodone, codeine, oxycodone and propoxyphene) and all other opioid medications. In comparison to 1995, use in 2009 increased significantly for all other opioid medications (aRR = 17.81, 95% CI = 12.88, 24.63), oxycodone (aRR = 4.03, 95% CI = 3.17, 5.11), and hydrocodone (aRR = 3.66, 95% CI = 3.32, 4.02), and use of codeine (aRR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.82, 1.03) and propoxyphene (aRR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.89, 1.21) did not significantly change.

Figure 2.

First trimester opioid use by individual medication: Tennessee Medicaid, 1995–2009

DISCUSSION

Results from this large, retrospective cohort of Tennessee Medicaid-insured pregnant women demonstrate roughly 2-fold increases in both early and later fetal exposure to opioid analgesics in the 15-year study period. Overall, more than 14% of pregnant women filled at least one prescription for an opioid analgesic with at least one days supply during the first trimester and approximately 21% of pregnant women filled at least one prescription for an opioid analgesic with at least one days supply in the second or third trimester. Women more likely to use an opioid analgesic during pregnancy were 21 years of age or older, white, non-Hispanic and prima gravid, with less than a high school education, residing in non-urban areas, and enrolled in Medicaid due to disability. First trimester use increased dramatically among women with opioid abuse or dependence diagnoses and with non-cancer pain diagnoses. Hydrocodone, codeine and oxycodone were the three most commonly used individual opioid analgesics during the first trimester.

Existing studies of opioid analgesic use in the United States have not specifically focused on use during pregnancy. The current study reports prevalence estimates in the 14–29% range and 2-fold increases over the 15-year study time period reported that were higher than expected but generally similar to what has been reported in other cohorts of Medicaid-insured patients. For example, one existing study using administrative claims data from the Arkansas Medicaid program reported that roughly 30% of patients with non-cancer pain conditions received opioids and that opioid analgesic use increased significantly from 2000 to 2005 [14]. Prescription opioid analgesic use in commercially-insured cohorts appears to be less prevalent than it is in cohorts of Medicaid enrollees but also to have increased significantly [5, 7, 14, 46].

Results of the current study are also generally consistent with previous studies identifying socio-demographic characteristics associated with opioid analgesic use in the general population. The current study and existing research have reported increased use among older persons, whites [47–50], individuals with less than a high school education [51, 52], patients residing in different geographic areas [1, 2, 15, 53–55], and persons with disabilities [12, 56]. Future research is needed to better understand the relationship between maternal socio-demographic characteristics, prescription opioid analgesic use, and adverse neonatal and maternal health outcomes.

The use of Medicaid data in the current study limits concern about the potential for selection bias, recall bias, and differential misclassification that often plagues retrospective cohort studies. Although one-third to one-half of all births in Tennessee and across the nation are Medicaid-insured events [38, 57–59], women continuously enrolled in Medicaid throughout pregnancy are typically younger, have fewer years of education, and have higher rates of disability and racial minority representation than pregnant women more generally [57]. Classifying medication use based on records of filled prescriptions does not allow for assessment of medication adherence, though pharmacy records have been shown to be concordant with patient self-reported medication use [38–40], use of common over-the-counter analgesics such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or illicit activities such as obtaining opioids without a prescription or filling opioid prescriptions for non-medical purposes including the intent to distribute.

Both early and later fetal exposure to prescription opioid analgesics may be associated with risk for mothers and their babies. Possible risks of opioid analgesic exposure to babies include birth defects with early fetal exposure [20–27, 60–65] and neonatal abstinence syndrome with later fetal exposure [28–34]. Prescribing opioid analgesics to treat medical conditions during pregnancy requires balancing the benefits to the mother with the potential risks to the developing fetus. Although the FDA does not require manufacturers to include on drug labels a recommendation against prescribing opioids to women during early pregnancy or specifically warn against potential risks of pregnancy-related use in patient-oriented educational materials [16, 17, 66], better information about the benefits and risks of pregnancy-related use are needed to guide clinical care. Given the increasing magnitude of pregnancy-related opioid analgesic use reported in the current study and the infeasibility of studying this issue via randomized clinical trials, future epidemiologic examination of potential risks associated with fetal exposure to opioid analgesics is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Epstein received financial support from Grant No. 5 K12HD043483. Dr. Bobo received financial support from Grant No. K23MH087747. The authors also wish to acknowledge the Bureau of TennCare and Tennessee Department of Health which provided study data. The work in this manuscript was presented at the BIRCWH Scholars Meeting and 7th Annual Interdisciplinary Women’s Health Research Symposium, Washington, D.C., November 2011, and at the 28th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management conference, Barcelona, Spain, August 2012.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Epstein, Martin, Wang, Chandrasekhar and Cooper, and Mr. Morrow report no potential conflicts of interest. In the past, Dr. Bobo has received grants/research support from Cephalon, Inc., and has served on speaker panels for Janssen Pharmaceutica and Pfizer, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zerzan JT, Morden NE, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D, Roughead E, Zhang F, et al. Trends and geographic variation of opiate medication use in state Medicaid fee-for-service programs, 1996 to 2002. Med Care. 2006;44(11):1005–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228025.04535.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis LH, Stoddard J, Radeva JI, Hutchison S, Dans PE, Wright A, et al. Geographic variation in the prescription of schedule II opioid analgesics among outpatients in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(3 Pt 1):837–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1–3):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Reynolds JL, Greenberg PE, Zhang M, Vallow S, et al. Estimated costs of prescription opioid analgesic abuse in the United States in 2001: a societal perspective. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(8):667–76. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210915.80417.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, Saunders K, Ray GT, Sullivan MD, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1166–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braden JB, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids by noncancer pain type 2000–2005 among Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore enrollees: results from the TROUP study. J Pain. 2008;9(11):1026–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braden JB, Sullivan MD, Ray GT, Saunders K, Merrill J, Silverberg MJ, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain among persons with a history of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL. A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997–2002. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(2):176–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: results from a national, population-based survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(3):280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen Y, Daumit GL, Ford DE. Opioid prescriptions by U.S. primary care physicians from 1992 to 2001. J Pain. 2006;7(4):225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MY, Woody G. Nonmedical use and abuse of scheduled medications prescribed for pain, pain-related symptoms, and psychiatric disorders: patterns, user characteristics, and management options. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(5):337–43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008;138(2):440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicero TJ, Surratt H, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Relationship between therapeutic use and abuse of opioid analgesics in rural, suburban, and urban locations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(8):827–40. doi: 10.1002/pds.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolphine [package insert] Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxycontin [package insert] Stamford, CT: Purdue Pharma LP; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Society of Addiction Medicine. Opioid Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction in Pregnancy: Committee Opinion #254. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1070–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256496e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Pain Medicine. Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: A statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine. American Academy of Pain Medicine; 2013. Feb, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zagon IS, Tobias SW, Hytrek SD, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid receptor blockade throughout prenatal life confers long-term insensitivity to morphine and alters mu opioid receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;59(1):201–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zagon IS, Verderame MF, Allen SS, McLaughlin PJ. Cloning, sequencing, expression and function of a cDNA encoding a receptor for the opioid growth factor, [Met(5)]enkephalin. Brain Res. 1999;849(1–2):147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zagon IS, Verderame MF, McLaughlin PJ. The biology of the opioid growth factor receptor (OGFr) Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;38(3):351–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zagon IS, Wu Y, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor and organ development in rat and human embryos. Brain Res. 1999;839(2):313–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Body and organ development of young rats maternally exposed to methadone. Biol Neonate. 1980;38(3–4):185–96. doi: 10.1159/000241363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaughlin PJ. Exposure to the opioid antagonist naltrexone throughout gestation alters postnatal heart development. Biol Neonate. 2002;82(3):207–16. doi: 10.1159/000063611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaughlin PJ, Wylie JD, Bloom G, Griffith JW, Zagon IS. Chronic exposure to the opioid growth factor, [Met5]-enkephalin, during pregnancy: maternal and preweaning effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71(1–2):171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, Friedman JM, Jann MW, Riehle-Colarusso T, et al. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):314.e1–314.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2320–2331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones HE, Martin PR, Heil SH, Kaltenbach K, Selby P, Coyle MG, et al. Treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women: clinical and research issues. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(3):245–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin PR, Arria AM, Fischer G, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, et al. Psychopharmacologic management of opioid-dependent women during pregnancy. Am J Addict. 2009;18(2):148–56. doi: 10.1080/10550490902772975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stine SM, Heil SH, Kaltenbach K, Martin PR, Coyle MG, Fischer G, et al. Characteristics of opioid-using pregnant women who accept or refuse participation in a clinical trial: screening results from the MOTHER study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(6):429–33. doi: 10.3109/00952990903374080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unger AS, Martin PR, Kaltenbach K, Stine SM, Heil SH, Jones HE, et al. Clinical characteristics of central European and North American samples of pregnant women screened for opioid agonist treatment. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16(2):99–107. doi: 10.1159/000284683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, Kaltenbach K, Coyle M, Fischer G, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40(2):199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creanga AA, Sabel JC, Ko JY, Wasserman CR, Shaprio-Mendoza CK, Taylor P, Barfield W, Cawthon L, Paulozzi LJ. Maternal drug use and its effect on neonates: a population-based study in Washington State. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):924–33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824ea276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns L, Mattick RP. Using population data to examine the prevalence and correlates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(5):487–92. doi: 10.1080/09595230701494416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piper JM, Mitchel EF, Jr, Snowden M, Hall C, Adams M, Taylor P. Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:758–768. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper WO, Ray WA, Griffin MR. Prenatal prescription of macrolide antibiotics and infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, Dudley JA, Dyer S, Gideon PS, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2443–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ray WA, Griffin MR. Use of Medicaid data for pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:837–849. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Strom BL, Guess HA, Hartzema A. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1103–1112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray WA. Population-based studies of adverse drug effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(17):1592–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piper JM, Mitchel EF, Jr, Ray WA. Expanded Medicaid coverage for pregnant women to 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilcosky TC, Chambless LE. A comparison of direct adjustment and regression adjustment of epidemiologic measures. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dupont WD. Statistical Modeling for Biomedical Researchers. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisner CM, Campbell CI, Ray GT, Saunders K, Merrill JO, Banta-Green C, et al. Trends in prescribed opioid therapy for non-cancer pain for individuals with prior substance use disorders. Pain. 2009;145(3):287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department analgesic prescription. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2067–73. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Albert JM, et al. The effect of race/ethnicity and desirable social characteristics on physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioid analgesics. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(11):1239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen I, Kurz J, Pasanen M, Faselis C, Panda M, Staton LJ, et al. Racial differences in opioid use for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, Senzel RS, Huang LL. “We don’t carry that”--failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(14):1023–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Hey L. Patterns and trends in opioid use among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29(8):884–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parsells Kelly J, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138(3):507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulozzi LJ, Xi Y. Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1002/pds.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simmons LA, Havens JR. Comorbid substance and mental disorders among rural Americans: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord. 2007;99(1–3):265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87(1):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Havens JR, Talbert JC, Walker R, Leedham C, Leukefeld CG. Trends in controlled-release oxycodone (OxyContin) prescribing among Medicaid recipients in Kentucky, 1998–2002. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):276–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ray WA, Gigante J, Mitchel EF, Jr, Hickson GB. Perinatal outcomes following implementation of TennCare. JAMA. 1998;279:314–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowen ME, Ray WA, Arbogast PG, Ding H, Cooper WO. Increasing exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(3):291, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA. Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:544–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bracken MB. Drug use in pregnancy and congenital heart disease in offspring. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(17):1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604243141717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bracken MB, Holford TR. Exposure to prescribed drugs in pregnancy and association with congenital malformations. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58(3):336–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rothman KJ, Fyler DC, Goldblatt A, Kreidberg MB. Exogenous hormones and other drug exposures of children with congenital heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(4):433–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaw GM, Malcoe LH, Swan SH, Cummins SK, Schulman J. Congenital cardiac anomalies relative to selected maternal exposures and conditions during early pregnancy. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8(5):757–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00145398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaw GM, Todoroff K, Velie EM, Lammer EJ. Maternal illness, including fever and medication use as risk factors for neural tube defects. Teratology. 1998;57(1):1–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199801)57:1<1::AID-TERA1>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zierler S, Rothman KJ. Congenital heart disease in relation to maternal use of Bendectin and other drugs in early pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(6):347–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508083130603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.U.S. Food and Drug Administratin. FDA Consumer Health Information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2012. Jul, FDA Works to Reduce Risk of Opioid Pain Relievers. [Google Scholar]