Abstract

Hepatic involvement is a common feature in childhood mitochondrial hepatopathies, particularly in the neonatal period. Respiratory chain disorders may present as neonatal acute liver failure, hepatic steatohepatitis, cholestasis, or cirrhosis with chronic liver failure of insidious onset. In recent years, specific molecular defects (mutations in nuclear genes such as SCO1, BCS1L, POLG, DGUOK, and MPV17 and the deletion or rearrangement of mitochondrial DNA) have been identified, with the promise of genetic and prenatal diagnosis. The current treatment of mitochondrial hepatopathies is largely ineffective, and the prognosis is generally poor. The role of liver transplantation in patients with liver failure remains poorly defined because of the systemic nature of the disease, which does not respond to transplantation. Prospective, longitudinal, multicentered studies will be needed to address the gaps in our knowledge in these rare liver diseases.

Structural and functional alterations of mitochondria are recognized as being responsible for a growing number of pathologic disorders, affecting the central and peripheral nervous system, skeletal and cardiac muscles, the liver, bone marrow, the endocrine and exocrine pancreas, the kidneys, and the intestines.1-3 Because the liver, with its biosynthetic and detoxifying properties, is highly dependent on adenosine triphosphate (ATP), hepatocytes contain a high density of mitochondria. Disorders affecting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) have a direct effect on mitochondrial and cellular metabolism, producing steatosis or cholestasis, hepatocyte death, and progressive liver injury.1,4-6 Mitochondrial hepatopathies occur primarily in early childhood; however, secondary disorders present at any age. Remarkable advances have been made recently in our understanding of mitochondrial hepatopathies, including the identification of the molecular basis of many disorders. The present review focuses on recent advances made in primary mitochondrial hepatopathies, including their genetics and management, and the future directions for research.

Structure, Function, and Genetics of Mitochondria

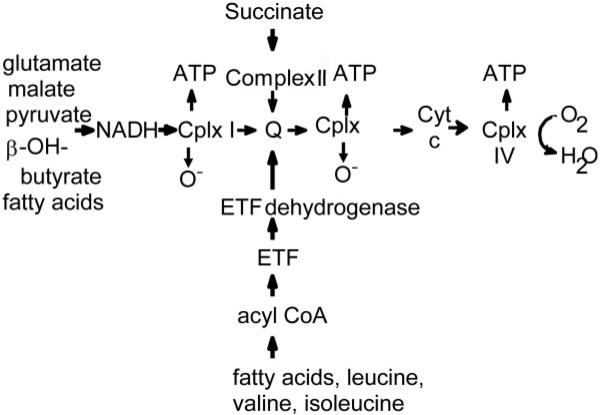

Mitochondria are double-membrane intracellular organelles and the main source of the high-energy phosphate molecule ATP, which is essential for all active intracellular processes.1 ATP is produced by the respiratory chain on the inner mitochondrial membrane by OXPHOS (Fig. 1).1 In this process, electron transfer proteins (NADH [reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide], FADH2 [reduced flavine adenine dinucleotide]), and electron transfer flavoprotein], which are reduced as a result of the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, donate electrons to complexes I and II and ubiquinones, which then flow down an electro-chemical gradient to ubiquinone complex III, cytochrome c, and finally complex IV, resulting in the active translocation of protons (H+) out of the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space, which establishes an electrochemical gradient. At complex V, protons flow back into the mitochondrial matrix, and the released energy is used to synthesize ATP.1,2

Fig. 1.

Respiratory chain protein complexes and oxidative phosphorylation of the mitochondria. Reducing equivalents derived from glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through a system of electron carriers (protein complexes I-IV, coenzyme Q, and cytochrome c) in the inner mitochondrial membrane through the efficient transport of electrons down this chain. This results in the generation of a transmembrane proton gradient that drives the synthesis of ATP by complex V, which is not shown (Cplx = complex; Cyt = cytochrome; ETF = electron transfer flavoprotein).

A unique feature of mitochondria in mammalian cells is the presence of a separate genome, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is distinct from that of the nucleus.4 A typical hepatocyte contains approximately 1000 copies of mtDNA. The respiratory chain peptide components are encoded by both nuclear and mtDNA genes. Thirteen essential polypeptides are synthesized from the small 16.5-kilobase circular double-stranded mtDNA, whereas nuclear genes encode more than 70 respiratory chain subunits and an array of enzymes and cofactors required to maintain mtDNA,1,3 including DNA polymerase γ (POLG), thymidine kinase 2 (TK2), and deoxyguanosine kinase (dGK).3 Mitochondrial DNA also encodes the 24 tRNAs required for intramitochondrial protein synthesis.1

One of the notable features in the genetics of mitochondrial cytopathies is that identical mutations in mtDNA may give rise to a wide variations in the severity and phenotypic expression. This is in large part explained by the concept of heteroplasmy, in which cells and tissues harbor both normal (wild-type) and mutant mtDNA in various amounts because of random partitioning during cell division. Disease expression is determined by the percentage of mutant mtDNA in a given cell or tissue,1,3 which may differ substantially among tissues or organs.

Classification of Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

A striking feature of mitochondrial disorders is their clinical heterogeneity: they range from single-organ in volvement to severe multisystem disease.1,7-9 Hepatic manifestations of mitochondrial disorders range from hepatic steatosis, cholestasis, and chronic liver disease with insidious onset to neonatal liver failure, which is frequently associated with neuromuscular symptoms.2 Sokol and Treem2 proposed a classification scheme for mitochondrial hepatopathies (Table 1), which include primary disorders, in which the mitochondrial defect is the primary cause of the liver disorder, and secondary disorders, in which a secondary insult to mitochondria is caused either by a genetic defect that affects nonmitochondrial proteins or by an acquired (exogenous) injury to mitochondria.4 Examples of secondary mitochondrial hepatopathies include Reye syndrome, Wilson's disease, valproic acid hepatotocixity, and the effects of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Leonard and Shapira10 further divided primary mitochondrial diseases into those caused by mutations affecting mtDNA genes (class 1a) and those caused by mutations in nuclear genes that encode mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins or cofactors (class 1b).

Table 1.

Classification of Primary Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

| 1. Electron transport (respiratory chain) defects |

| • Neonatal liver failure |

| Complex I deficiency |

| Complex IV deficiency (SCO1 mutations) |

| Complex III deficiency (BCS1L mutations) |

| Multiple complex deficiencies |

| • Mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome (DGUOK, MPV17, and POLG mutations) |

| • Delayed onset liver failure: Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome (POLG mutations) |

| • Pearson marrow-pancreas syndrome (mitochondrial DNA deletion) |

| • Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (TP mutations) |

| • Chronic diarrhea (villus atrophy) with hepatic involvement (complex III deficiency) |

| • Navajo neurohepatopathy (mitochondrial DNA depletion; MPV17 mutations) |

| • Electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) and ETF-dehydrogenase deficiencies |

| 2. Fatty acid oxidation and transport defects |

| • Long-chain hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency |

| • Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (long-chain hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase enzyme mutations) |

| • Carnitine palmitoyl transferase I and II deficiencies |

| • Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency |

| • Fatty acid transport defects |

| 3. Disorders of mitochondrial translation process |

| 4. Urea cycle enzyme deficiencies |

| 5. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase deficiency (mitochondrial) |

This table was adapted from J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;28:4-16 and is used by permission.

Prevalence of Primary Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

Recent studies have shown that mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders of all types affect 1 in 20,000 children under 16 years of age.11 In a population-based study on the prevalence of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies in Sweden, liver involvement was noted in 20% of the cases studied.12 In another study of 1041 children from a tertiary referral center, 22 (10%) of the 234 patients with respiratory chain defects had liver dysfunction, whereas 10 patients had the onset of liver disease in the neonatal period.7 Given the heterogeneity of the features and difficulties with diagnosis, these figures are likely to be underestimates of the true prevalence of these disorders.

Clinical Features of Primary Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

Neonatal Liver Failure

Mitochondrial hepatopathies involving the respiratory chain frequently present as acute liver failure with onset within the first weeks to months of life and are associated with lethargy, hypotonia, vomiting, poor suck, and seizures (Table 2).7,8 In others, after an initial normal course, a viral infection or some other undefined inciting event triggers hepatic and, sometimes, neurologic deterioration.9 Key biochemical features include a markedly elevated plasma lactate concentration, an elevated molar ratio of plasma lactate to pyruvate (>20 and frequently >30 mol/mol), and a raised beta-hydroxybutyrate and arterial ketone body ratio of beta-hydroxybutyrate to acetoacetate (>2.0 mol/mol).5 Respiratory chain complex analysis of the liver or muscle generally shows low activity of complex I, III, or IV (Table 3). In most of these infants, liver failure progresses to death within weeks to months after presentation, although occasionally infants have recovered or have undergone successful liver transplantation. Most infants also have severe neurological involvement developing in infancy with a weak cry, hypotonia, recurrent apnea, and myoclonic epilepsy.7,8

Table 2.

Hepatic and Extrahepatic Features of Primary Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

| Disorder | Onset | Age at Onset | Liver Disease | Extrahepatic Features | Seizures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal liver failure | Acute | Early neonatal | Neonatal liver failure | Lethargy, hypotonia, vomiting, poor suck from birth, apnea | ± |

| mtDNA depletion | Acute/chronic | Early neonatal | Hepatomegaly, progressive liver failure; death within a few months; steatosis, cholestasis, fibrosis, iron deposition | Hypotonia, psychomotor delay, nystagmus, failure to thrive, feeding difficulties; less common: pyramidal signs, cardiomegaly, tubulopathy, amyotrophia | + |

| Delayed onset liver disease (Alpers-Huttenlocher) | Insidious | Children and young adults | Hepatomegaly, jaundice, raised liver enzymes, cirrhosis, and progressive liver failure | Liver failure preceded by neurological symptoms, psychomotor regression, vomiting; partial motor epilepsy or multifocal myoclonus, characteristic EEG | ++ |

| Pearson syndrome | Insidious | Infancy | Hepatomegaly, cholestasis raised liver enzymes, progressive liver failure; death in early childhood | Refractory sideroblastic anemia, vacuolization of marrow precursors, variable neutropenia and thrombocytopenia | - |

| Villous atrophy syndrome | Chronic | Early childhood | Hepatomegaly, raised liver enzymes; microvesicular steatosis | Vomiting, anorexia, chronic diarrhea, villus atrophy, diabetes mellitus, cerebellar ataxia, sensorineural deafness, retinitis pigmentosa, seizures | ± |

| Navajo neurohepatopathy | Acute or chronic | Infancy to childhood | Jaundice, ascites, Reye syndrome-like episodes, progressive cirrhosis and liver failure; death in early childhood | Sensorimotor neuropathy, corneal anesthesia, acral mutilation, progressive CNS white matter lesions | - |

NOTE. This table was adapted from J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;28:4-16 and is used by permission. ++, present always; ±, occasionally present; -, not present; CNS, central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalogram; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Table 3.

Laboratory Features of Primary Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

| Disorder | Plasma Lactate | L/P Ratio | mtDNA | Respiratory Chain Complexes Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal liver failure | ↑ | ↑ | Normal | IV, III, or I |

| mtDNA depletion syndrome | ↑ | ↑ | Depletion | I, III, IV |

| Delayed onset liver disease (Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome) | Normal | Normal | Normal | I |

| Pearson syndrome | Normal or ↑ | Normal or ↑ | Deletion | I, III |

| Villous atrophy syndrome | ↑ | ↑ | Rearrangements | III |

| Navajo neurohepatopathy | ± | ± | Depletion | I, III, IV |

NOTE. This table was adapted from J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;28:4-16 and is used by permission. ±, present occasionally; ↑, increased; L/P ratio, molar ratio of plasma lactate to pyruvate; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Syndrome (MDS)

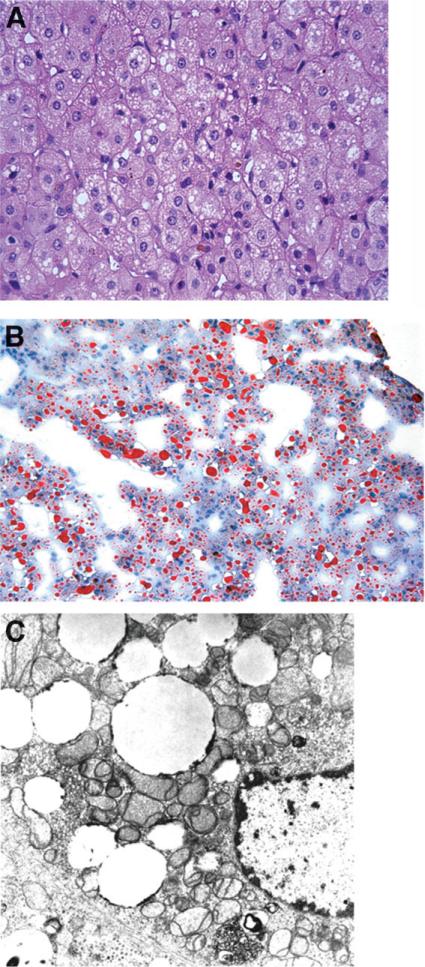

MDS is defined as a reduction in the mtDNA copy number in different tissues leading to insufficient synthesis of respiratory chain complexes I, III, IV, and V.3,13 Affected patients generally present with a severe form of liver failure in infancy.5,6 There are 2 clinical phenotypes of MDS, a myopathic form and a hepatocerebral form, with considerable phenotypic heterogeneity within both forms.13 Patients with the hepatocerebral form present within the first weeks of life with hepatomegaly and progressive liver failure leading to death a few months later.5,6,14 Presenting symptoms include vomiting, severe gastroesophageal reflux, failure to thrive, or developmental delay. Lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, moderately raised serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, coagulopathy, and elevated total and conjugated bilirubin are common.5,6 Neurological abnormalities include hypotonia, Leigh syndrome, nystagmus, psychomotor delay, pyramidal signs, seizures, and cataracts.5,6 The liver histology is characterized by macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis, hepatocytic and canalicular cholestasis, fibrosis, and iron deposition in hepatocytes and sinusoidal cells (Fig. 2).6 There is considerable overlap between the clinical and laboratory features of MDS and the neonatal liver failure form of respiratory chain disease. The major difference between the 2 conditions is the demonstration in MDS of a low ratio (<10%) of the normal amount of mtDNA to nuclear DNA in affected tissues, with a normal mtDNA genome sequence (Table 3).6

Fig. 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of liver biopsy from a 3-month-old child with POLG mutations and mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome, showing microvesicular steatosis, cholestasis with bile pigment in canaliculi and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes (hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification ×200). (B) Oil-red-O stain demonstrating microvesicular deposits of the neutral lipid (magnification ×100). (C) Electron micrograph from the same patient showing small vesicles of lipid and pleomorphic, distorted mitochondria (magnification ×13,700).

Alpers-Huttenlocher Syndrome (Delayed-Onset Liver Disease)

The generally accepted diagnostic criteria are as follows: (1) refractory, mixed-type seizures that include a focal component; (2) psychomotor regression that is often episodic and triggered by intercurrent infections; and (3) hepatopathy with or without acute liver failure.15 Typically, the onset of symptoms occurs between 2 months and 8 years of life and is characterized by hepatomegaly, jaundice, and progressive coagulopathy and hypoglycemia.16 In most of these children, liver failure is preceded by the development of hypotonia, feeding difficulties, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux or intractable vomiting, failure to thrive, and ataxia followed by the onset of refractory partial motor epilepsy or multifocal myoclonus.16,17 Multiple anticonvulsants are usually necessary to control the seizures. The use of valproic acid may exacerbate the deficiency of respiratory chain enzyme activity and precipitate liver failure.18

Progressive neurologic deterioration may ensue rapidly. In other children, the neurologic features are less severe or of somewhat later onset. There may be elevated blood or CSF lactate and pyruvate levels, characteristic electroencephalogram findings (high-amplitude slow activity with polyspikes),17 asymmetric abnormal visual evoked responses,17 and low-density areas or atrophy in the occipital or temporal lobes on computed tomography scanning of the brain.19 In some patients, NADH oxidoreductase (complex I) deficiency has been found in liver or muscle mitochondria.7,20

Pearson Syndrome

Pearson marrow-pancreas syndrome was first described in 1979 in 4 children with neonatal-onset severe macrocytic anemia, variable neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, vacuolization of marrow precursors, and ringed sideroblasts in the bone marrow.21 Later in infancy or early childhood, diarrhea and fat malabsorption developed because of pancreatic insufficiency caused by extensive pancreatic fibrosis and acinar atrophy. Partial villous atrophy of the small intestine was also noted. The liver involvement is manifested as marked hepatomegaly, hepatic steatosis, and cirrhosis. Liver failure and death in some cases have been reported before the age of 4 years.22

Other clinical manifestations of Pearson syndrome include renal tubular disease (Fanconi's syndrome), patchy erythematous skin lesions and photosensitivity, diabetes mellitus, hydrops fetalis, and the late development of visual impairment, tremor, ataxia, proximal muscle weakness, external ophthalmoplegia, and a pigmentary retinopathy. Deletions of mtDNA segments are reported in most patients. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria is also present in Pearson syndrome and is regarded as a useful marker for this disorder.23

Villous Atrophy Syndrome

This rare disease was first described by Cormier-Daire et al.24 in 2 unrelated children with severe anorexia, vomiting, chronic diarrhea, and villus atrophy in the first year of life. The hepatic involvement was characterized by a mild elevation of aminotransferases, hepatomegaly, and steatosis. Diarrhea, vomiting, and lactic acidosis worsened with high dextrose intravenous infusions or enteral nutrition. Diarrhea improved and even resolved completely by 5 years of age in association with the normalization of intestinal biopsies. The subsequent course of the disease was complicated by retinitis pigmentosa, cerebellar ataxia, sensorineural deafness, and proximal muscle weakness, with eventual death late in the first decade of life. Respiratory chain enzyme assays were normal in circulating lymphocytes; however, a complex III deficiency was demonstrated in skeletal muscle.

Navajo Neurohepatopathy (NNH)

NNH is a sensorimotor neuropathy with progressive liver disease that is confined to Navajo children.25 This disorder is manifested by the development of weakness, hypotonia, areflexia, loss of sensation in the extremities, acral mutilation, corneal ulceration, poor growth, short stature, and serious systemic infections.25,26 Reye-like syndrome episodes, cholestasis, cirrhosis, or liver failure occurs in infancy or childhood. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows the presence of progressive white matter lesions, and peripheral nerve biopsies show a severe loss of myelinated fibers.25,26 There are 3 clinical presentations of NNH, including (1) an infantile presentation, with failure to thrive and jaundice progressing to hepatic failure and death within the first 2 years of life, with or without neurologic findings; (2) a childhood form presenting between 1 and 5 years of age, with rapid development of liver failure; and (3) the classical form in which progressive neurological findings dominate, although liver dysfunction (and even cirrhosis) is present in all patients. The liver histology demonstrates portal fibrosis or micronodular cirrhosis, macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis, pseudoacinar formation, multinucleated giant cells, cholestasis, and periportal inflammation.25 The liver involvement is progressive, with liver failure developing within months to years in most patients. There has been no effective treatment to date for affected children.

Genetics of Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

Although more than 200 pathogenic point mutations, deletions, insertions, and rearrangements have been identified since the first mtDNA mutations were reported in 1988,27 much remains to be known about the genetics of mitochondrial hepatopathies. It is now clear that most mitochondrial diseases with primary involvement of the liver are caused by nuclear, rather than mitochondrial, DNA mutations (Table 4).28,29

Table 4.

Molecular Causes of Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

| Disorder | Gene | Protein | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear genes | ||||

| Neonatal liver failure | SCO1 | Copper chaperone of complex IV (COX) | Transfers copper from Cox17p to COX subunits I and II | 33, 34 |

| BCS1L | Assembly protein of complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase) | Catalyzes the electron transfer from coenzyme Q to cytochrome c | 35, 36 | |

| mtDNA depletion syndrome | POLG | mtDNA pol γ | Pol γ activity is essential for mtDNA replication and repair. Defective pol γ leads to mtDNA depletion. | 43 |

| DGUOK | dGK, mitochondrial nucleotide salvaging | dGK, together with TK2, functions to maintain the supply of dNTPs for mtDNA synthesis. | 40-42 | |

| MPV17 | Mitochondrial inner membrane | mtDNA maintenance and regulation of protein OXPHOS. Absence or malfunction causes OXPHOS failure and mtDNA depletion. | 28, 44 | |

| Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome | POLG | See above | See above | 45, 46 |

| Navajo Neurohepatopathy | MPV17 | See above | See above | 29, 50 |

| mtDNA | ||||

| Pearson syndrome | mtDNA deletion (most common from nt 8488 to nt 13,460) | Synthesis of complexes III and I | Deficiencies of complexes III and I | 52, 53 |

| Villous atrophy syndrome | mtDNA rearrangement | Synthesis of complex III | Deficiency of complex III | 24 |

Abbreviations: COX, cytochrome c oxidase; dGK, deoxyguanosine kinase; dNTP, deoxyribonucleotide; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; pol γ, polymerase γ; TK2, thymidine kinase 2.

Neonatal Liver Failure

Low hepatic activity of respiratory chain complexes IV, I, III, and occasionally II, either in isolation or in combination, has been found in infants with this presentation.7,30,31 Among these, a deficiency of complex IV [cytochrome c oxidase (COX)] is the most common cause. COX is the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain that catalyzes the transfer of reducing equivalents from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen (Fig. 1).32 This exergonic reaction is coupled with COX-mediated proton translocation from the matrix to cytosol.32 The mammalian COX is a heterooligomer composed of 13 subunits. The 3 largest subunits forming the catalytic core of the enzyme are encoded by mtDNA, whereas the remaining 10 subunits involved in the assembly and regulation of the enzyme are encoded by nuclear DNA.32

SCO1 Gene

In 1 affected family with predominantly hepatic failure in infancy, lactic acidosis, and neurodevelopmental delays, mutations in the COX assembly nuclear gene SCO1 have been associated with COX deficiency.33 The SCO1 gene, located at chromosome 17p13.1, is believed to encode a protein functioning as a copper chaperone that transfers copper from Cox17p, a copper-binding protein of the cytosol and mitochondrial intermembrane space, to the mitochondrial COX subunit II.34 The mutation analysis of affected patients in a family showed compound heterozygosity for the SCO1 gene.33 A mutated allele inherited from the father showed a 2–base-pair frameshift deletion (ΔGA; nucleotides [nt] 363-364) resulting in both a premature stop codon and a highly unstable mRNA. The maternally inherited mutation (C520T) changed a highly conserved proline into a leucine in the protein (P174L).33 This proline, adjacent to the CxxxC copper-binding domain of SCO1, is likely to play a crucial role in the tridimensional structure of the domain.

BCS1 Gene

Complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex) catalyzes the electron transfer from coenzyme Q to cytochrome c. BCS1L is a nuclear gene encoding proteins involved in the assembly of respiratory complex III. A mutation in BCS1L has been found to be associated with mitochondrial neonatal liver failure.35 De Lonlay et al.35 reported deficient activity of complex III of the respiratory chain in the liver, fibro-blasts, or muscle in affected infants with hepatic failure, lactic acidosis, renal tubulopathy, and variable degrees of encephalopathy. Three mutations in BCS1L were demonstrated in 3 affected families. Subsequently, de Meirleir et al.36 confirmed that mutations in BCS1L were associated with fatal complex III deficiency and liver failure in 2 siblings. These included missense mutation R45C and nonsense mutation R56X, both located in the exon 1 of BCS1L gene. It is likely that mutations in BCS1L are responsible for a substantial number of infants who present with neonatal liver failure and lactic acidosis.

MDS

The mtDNA processing enzyme activities are dependent on several factors, including deoxyribonucleotide (dNTP) concentrations within the mitochondria, the availability of ATP, and several metal cofactors.37 An imbalance of any of these cofactors or enzymes could affect mtDNA stability. The mtDNA pool is maintained either by the import of cytosolic dNTPs through dedicated transporters or by the salvaging of deoxynucleosides within the mitochondria. The mitochondrial deoxynucleoside salvage pathway is regulated by nuclear-encoded enzymes, including dGK and TK2.38,39 Human dGK phosphorylates deoxyguanosine and deoxyadenosine, whereas TK2 phosphorylates deoxythymidine, deoxycytidine, and deoxyuridine. An imbalance of this mitochondrial dNTP pool has been proposed to be responsible for both the hepatocerebral and myopathic forms of MDS.40 In 2001, mutations in 2 genes involved in this pathway were identified in patients with MDS: deoxyguanosine kinase (DGUOK) in the hepatocerebral form and TK2 in the myopathic form.40,41

DGUOK

Mandel et al.,40 using homozygosity mapping in 3 consanguineous kindreds affected with hepato-cerebral MDS, mapped this disease to chromosome 2p13, which encompasses the gene DGUOK encoding dGK. A single-nucleotide deletion (204delA) within the coding region of DGUOK was identified.40 The reduction of enzymatic activities of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes containing mtDNA encoded subunits (complexes I, III, and IV but not complex II, which is solely encoded by nuclear genes) was demonstrated in the liver but not in muscle, showing the tissue-specific nature of this disorder. However, Salviati et al.42 screened the frequency of DGUOK mutations in 21 patients with hepatocerebral MDS and noted that DGUOK mutations were present in only 14%, suggesting this was not the only gene responsible for MDS in the liver.42 No genotype-phenotype correlation was demonstrated.

POLG and MPV17

Two other nuclear genes have recently been linked to the hepatocerebral form of MDS. Mutations in DNA POLG, which is confined to mitochondria but encoded by a nuclear gene, have now been described in infants with MDS and in older children with Alpers-Huttenlocher disease.43,44 Most of the cases with MDS in early childhood are associated with at least 1 mutation in the linker region of POLG and 1 in the polymerase domain. More recently, Spinazzola et al.28 used a novel integrative genomics approach to discover mutations in the nuclear gene MPV17 in 3 families affected by the hepatocerebral form of MDS. This gene encodes an inner mitochondrial membrane protein of uncertain function.

Alpers-Huttenlocher Syndrome

Mutations in POLG have recently been shown to be common in patients with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome.45,46 The mtDNA polymerase γ (pol γ) is essential for mtDNA replication and repair.47 Pol γ is composed of a 140-kDa catalytic (α) subunit that contains DNA polymerase, 3′-5′ exonuclease, and dRP [deoxyribose phosphate] lyase activities and a 55-kDa accessory (β) subunit that functions as a processivity and DNA binding factor.47 A deficiency in mitochondrial pol γ activity and mtDNA depletion was first reported in a patient with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome by Naviaux et al. in 1999.48 Subsequently, Naviaux and Nguyen45 reported that in 2 unrelated pedigrees with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome, each affected child was found to harbor a homozygous mutations in exon 17 of POLG that led to a Glu873Stop mutation just upstream of the polymerase domain of the protein. In addition, each affected child was heterozygous for the G1681A mutation in exon 7, which led to an Ala467Thr substitution in pol γ, within the linker region of the protein.45

The discovery of the association between POLG gene mutations and Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome has led to the advent of the molecular diagnosis of Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome.46 Nyugen et al.46 sequenced the POLG locus in 15 sequential probands with the clinical features of Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome and noted that POLG DNA testing accurately diagnosed 87% of cases. Few new POLG amino acid substitutions (F749S, R852C, T914P, L966R, and L1173fsX) were reported. The most common mutation was the Ala467Thr substitution described previously, which accounted for about 40% of the alleles and was present in 65% of the patients.46 All patients with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome had either Ala467Thr or W748S substitution in the linker region.

Mutations in POLG have also been associated with another severe form of hepatocerebral syndrome, autosomal dominant or recessive progressive external ophthalmoplegia, neuropathy, ataxia, hypogonadism, migraine, hearing loss, muscle weakness, parkinsonism, and psychiatric symptoms.44,49

NNH and MPV17 Gene Mutation

Vu et al.29 first demonstrated mtDNA depletion in liver biopsies from 2 patients with NNH, which was consistent with the hypothesis that a nuclear gene might be responsible for this autosomal recessive disease. A genome-wide scan, performed with 400 DNA microsatellite markers, demonstrated mapping of the disease to chromosome 2p24.1.29MPV17, the gene associated with MDS, was mapped to this region. The MPV17 product is involved in mtDNA maintenance and in the regulation of OXPHOS28 and is localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane.28 The sequencing of MPV17 in 6 NNH patients from 5 families in 2006 demonstrated the same homozygous disease-causing R50Q mutations in exon 2 in all patients, confirming a founder effect in this disease.50 Thus, it is now clear that NNH is indeed a form of mtDNA depletion with a unique clinical presentation in Navajos.

Pearson Syndrome

The association of Pearson syndrome and a specific deletion in mtDNA was first reported in 1990 by Rotig et al.51 It is now established that mtDNA rearrangements are present in all patients with Pearson syndrome, with large (4000-5000 base pairs) deletions predominating in three-quarters of reported cases.23,52,53 The most common deletion is located between nt 8488 and nt 13,460.54 The proteins affected by this deletion include respiratory chain enzymes (complex I is the most severely affected), 2 subunits of complex V, 1 subunit of complex IV, and 5 transfer RNA genes. Other mtDNA deletions of differing lengths are associated with clusters of the characteristic clinical manifestations.51,53 Rotig et al.51 reported a 5-year-old boy with sideroblastic anemia, persistent diarrhea, lactic acidosis, and liver failure with a 3.1-kilobase deletion (nt 6074-9179). In contrast, Jacobs et al.53 described a patient with anemia and diarrhea but no pancreatic or hepatic involvement with a 3.4-kilobase deletion (nt 6097-9541). Heteroplasmy of mtDNA in different tissues may explain these discrepant findings.

Villous Atrophy Syndrome

Villous atrophy syndrome has been recognized as an mtDNA rearrangement defect.26 A complex III deficiency was found in the muscle of affected patients. Southern blot analysis showed evidence of heteroplasmic mtDNA rearrangements that involved deletion and deletion duplication.26 Two different mutations were described in the 2 children reported.26 In 1 patient, a deletion spanning 3380 base pairs encompassed 3 genes for complex I and 3 transfer ribonuclease genes. The deletion in the second patient was larger.

Treatment of Mitochondrial Hepatopathies

The treatment of acute liver failure and progressive liver disease in mitochondrial hepatopathies remains unsatisfactory. Present treatments have been palliative or involved the use of various vitamins, cofactors, respiratory substrates, or antioxidant compounds, with the aim of mitigating, postponing, or circumventing the damage to the respiratory chain.2,55 None of these therapies has been proven to be universally effective. Supportive treatments may also include the infusion of sodium bicarbonate for acute metabolic acidosis, transfusions for anemia and thrombocytopenia, and exogenous pancreatic enzymes for pancreatic insufficiency. Although coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone) has been reported to result in sustained improvement in patients with myopathies caused by coenzyme Q deficiency or complex III deficiency, there is little reported experience in mitochondrial hepatopathies.56

Liver Transplantation

There is at present no consensus on the role of liver transplantation in mitochondrial hepatopathies, largely because of the multisystemic nature of this disorder.57,58 A review of the literature showed a mixed outcome, with a survival rate of less than 50% (Table 5).57-61 The presence of significant neuromuscular and cardiovascular involvement is an absolute contraindication to liver transplantation as a therapeutic option, inasmuch as extrahepatic clinical disease continues to progress to death following transplantation.57-59 It also appears that clear intestinal symptomatology (and hence presumed intestinal involvement) portends a poor prognosis after liver transplantation.57 Other patients who have unrecognized neurological involvement before transplantation may develop neuro-muscular symptomatology only after transplantation.58 Thus, the absence of extrahepatic features of mitochondrial disease at the time of liver transplantation does not guarantee a good outcome even if the transplant is successful.

Table 5.

Outcome of Liver Transplantation in Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Disorders

| Case | Age at Onset (Months) | Fulminant | Organs Involved | Outcome After OLT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sokal et al.59 | ||||

| 1 | 3 | Y | L | Alive and well, 3 years |

| 2 | 7 | Y | L, gut | Mental retardation, died at 19 months after OLT |

| 3 | Neonate | Y | L, gut | Early post-OLT death |

| 4 | 6 | Y | L | Alive and well, 6 months |

| 5 | 3 | N | L | Early post-OLT death, MOF |

| 6 | 3 | N | L | Alive and well, 5 months after OLT |

| 7 | 3 | N | L | Alive and well, 8 years after OLT |

| 8 | 1 | Y | L, gut | Early post-OLT death, MOF |

| 9 | 2 | Y | L | Alive and well, 2 years |

| Thomson et al.58* | ||||

| 10 | 4 | Y | L | Died 9 months after OLT, neurological deterioration |

| 11 | 4 | Y | L | Died 6 months after OLT, neurological deterioration |

| Dubern et al.59 | ||||

| 12 | Neonate | N | L | Died 11 months after OLT, neurological deterioration |

| 13 | 6 | Y | L | Alive at 28 months, mental retardation |

| 14 | 4 | Y | L | Early post-OLT death, MOF |

| 15 | 3 | Y | L | Alive and well, persistent acidosis |

| 16 | 3 | N | L | Alive and well, 2 years |

| Delarue et al.60 | ||||

| 17 | 3 years | Y | L | Died 4 months after OLT, neurological deterioration |

| Robinowitz et al.61 | ||||

| 18 | Neonate | N | L | Died a few months after OLT, MOF |

Abbreviations: L, liver; MOF, multiorgan failure; N, no; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation; Y, yes.

The 2 cases contributed by McKiernan from Birmingham Children's Hospital (United Kingdom) in the original series by Sokal et al. were also reported separately by Thomson et al. (personal communication).

This said, there have been patients who have had a successful liver transplantation with isolated liver involvement. Careful and thorough pretransplant screening of potentially affected organ systems [kidneys, heart, muscle, intestinal tract, central nervous system (CNS), and pancreas] is therefore essential. This is especially problematic in patients presenting with acute liver failure and associated acute neurological decompensation. Improved diagnostic techniques and predictive biomarkers to assist with selecting the best candidates for liver transplantation are certainly needed.

Recently, both MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy have been used increasingly in the evaluation of CNS disease in patients with acute liver failure due to mitochondrial hepatopathies before liver transplantation.59,62,63 In a series of 5 patients with mitochondrial hepatopathies who had liver transplants, as reported by Dubern et al.,59 4 patients had cranial MRI as part of the assessment before transplantation. One patient who had cortical atrophy on cranial MRI had slight motor retardation and remained clinically stable after transplantation. Of the remaining 3 patients, who all had normal cranial MRI before transplantation, 1 patient died of immediate posttransplant complications, 1 had progressive microcephaly after transplantation, and the other patient had no neurological involvement.59 Thus, although cranial MRI is a useful investigation tool in the assessment of CNS involvement in patients with acute liver failure caused by mitochondrial hepatopathies before liver transplantation, normal cranial MRI does not preclude subsequent neurological deterioration.

Future Research Directions

Although remarkable advances have been made in recent years that help us to elucidate the genetic etiology of mitochondrial hepatopathies, there remain many gaps in our knowledge of these disorders. Little is known about the overall frequency, full spectrum of hepatic involvement, and long-term natural history of these disorders. Diagnostic evaluation is evolving toward genotyping the most likely involved genes; however, more rapid and predictable diagnostic techniques (e.g., needle liver biopsy analysis of respiratory chain enzymes) still need to be developed and made widely accessible. Genotype-phenotype correlations and the relationship of the genotype to the response to liver transplantation await prospective large-scale studies. There are also undoubtedly other genetic causes that will be identified in coming years. A feasible and effective treatment is, at present, not available, and the precise role of liver transplantation needs to be better defined. Finally, the role of polymorphisms in genes causing these disorders as potential modifiers in other disorders of the liver may identify new targets for therapeutic approaches. The Cholestatic Liver Disease Consortium, a National Institutes of Health–funded, multicentered Rare Disease Clinical Research Consortium,64 is attempting to address many of these questions.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (MOI RR00069, ROI DK038446, UOIDK062453, and U54DK078377) and the Fulbright Scholarship.

W. S. Lee was a visiting Fulbright Scholar from the Department of Paediatrics of the University of Malaya Medical Centre (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) to the Section of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition of the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children's Hospital (Denver, CO).

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CNS

central nervous system

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- Cplx

complex

- Cyt

cytochrome

- dGK

deoxyguanosine kinase

- DGUOK

deoxyguanosine kinase

- dNTP

deoxyribonucleotide

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- ETF

electron transfer flavoprotein

- L/P ratio

molar ratio of plasma lactate to pyruvate

- MDS

mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome

- MOF

multiorgan failure

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- NNH

Navajo neurohepatopathy

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplant

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- pol γ

polymerase γ

- POLG

polymerase γ

- TK2

thymidine kinase 2

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Chinnery PF, DiMauro S. Mitochondrial hepatopathies. J Hepatol. 2005;43:207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokol RJ, Treem WR. Mitochondria and childhood liver diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:4–16. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial respiratory-chain diseases. N Eng J Med. 2003;348:2656–2668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns DR. Mitochondrial DNA and disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:638–644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509073331007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris AA, Taanman JW, Blake J, Cooper JM, Lake BD, Malone M, et al. Liver failure associated with mitochondrial DNA depletion. J Hepatol. 1998;28:556–563. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labarthe F, Dobbelaere D, Devisme L, De Muret A, Jardel C, Taanman JW, et al. Clinical, biochemical and morphological features of hepatocerebral syndrome with mitochondrial DNA depletion due to deoxyguanosine kinase deficiency. J Hepatol. 2005;43:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormier-Daire V, Chretien D, Rustin P, Rotig A, Dubuisson C, Jacquemin E, et al. Neonatal and delayed-onset liver involvement in disorders of oxidative phosphorylation. J Pediatr. 1997;130:817–822. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Cazorla A, De Lonlay P, Nassogne MC, Rustin P, Touati G, Saudubray JM. Long-term follow-up of neonatal mitochondrial cytopathies: a study of 57 patients. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1170–1177. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holve S, Hu D, Shub M, Tyson RW, Sokol RJ. Liver disease in Navajo neuropathy. J Pediatr. 1999;135:482–493. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard JV, Shapiro AHV. Mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders I: mitochondrial DNA defects. Lancet. 2000;355:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skladal D, Halliday J, Thornburn DR. Minimum birth prevalence of mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders in children. Brain. 2003;126:1905–1912. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darin N, Oldfors A, Moslemi AR, Holme E, Tulinius M. The incidence of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies in childhood: clinical features and morphological, biochemical, and DNA abnormalities. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moraes CT, Shanske S, Tritschler HJ, Aprille JR, Andreetta F, Bonilla E, et al. mtDNA depletion with variable tissue expression: a novel genetic abnormality in mitochondrial diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:492–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker HD, Scholte HR, Dingemans KP, Spelbrink JN, Wijburg FA, Van der Bogert C. Depletion of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid in a family with fatal neonatal liver disease. J Pediatr. 1996;128:683–687. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)80135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding BN. Progressive neuronal degeneration of childhood with liver disease (Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome): a personal review. J Child Neurol. 1990;5:273–287. doi: 10.1177/088307389000500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narkewicz MR, Sokol RJ, Beckwith B, Sondheimer J, Silverman A. Liver involvement in Alpers disease. J Pediatr. 1991;118:260–267. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80736-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd SG, Harden A, Egger J, Pampiglione G. Progressive neuronal degeneration of childhood with liver disease (“Alpers’ disease”): characteristic neurophysiological features. Neuropediatrics. 1986;17:75–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzoulis C, Engelsen BA, Telstad W, Aasly J, Zeviani M, Winterthun S, et al. The spectrum of clinical disease caused by the A467T and W748S POLG mutations: a study of 26 cases. Brain. 2006;12(pt 7):1685–1692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger J, Harding BN, Boyd SG, Wilson J, Erdohazi M. Progressive neuronal degeneration of childhood (PNDC) with liver disease. Clin Pediatr. 1987;26:167–173. doi: 10.1177/000992288702600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gauthier-Villars M, Landrieu P, Cormier-Daire V, Jacquemin E, Chretien D, Rotig A, et al. Respiratory chain deficiency in Alpers syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 2001;32:150–152. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson HA, Lobel JS, Kocoshis SA, Naiman JL, Windmiller J, Lammi AT, et al. A new syndrome of refractory sideroblastic anemia with vacuolization of marrow precursors and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction. J Pediatr. 1979;95:976–984. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morikawa Y, Matsuura N, Kakudo K, Higuchi R, Koike M, Kobayashi Y. Pearson's marrow/pancreas syndrome: a histological and genetic study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;423:227–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01614775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson KM, Bennett MJ, Mize CE, Jakobs C, Rotig A, Munnich A, et al. 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria associated with Pearson syndrome and respiratory chain defects. J Pediatr. 1992;121:940–942. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cormier-Daire V, Bonnefont JP, Rustin P, Maurage C, Ogier H, Schmitz J, et al. Mitochondrial DNA rearrangement with onset as chronic diarrhea with villous atrophy. J Pediatr. 1994;124:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holve S, Hu D, Shub M, Tyson RW, Sokol RJ. Liver disease in Navajo neuropathy. J Pediatr. 1999;135:482–493. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singleton R, Helgerson SD, Snyder RD, O'Conner PJ, Nelson S, Johnsen SD, et al. Neuropathy in Navajo children: clinical and epidemiologic features. Neurology. 1990;40:363–367. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt IJ, Harding AE, Morgan-Hughes JA. Deletions of muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients with mitochondrial myopathies. Nature. 1988;331:717–719. doi: 10.1038/331717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinazolla A, Viscomi C, Fernandez-Vizarra E, Carrara F, D'Adamo P, Calvo S, et al. MPV17 encodes an inner mitochondrial membrane protein and is mutated in infantile hepatic mitochondrial DNA depletion. Nat Genet. 2006;38:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vu TH, Tanji K, Holve SA, Bonilla E, Sokol RJ, Snyder RD, et al. Navajo neurohepatopathy: a mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome? HEPATOLOGY. 2001;34:116–120. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cormier V, Rustin P, Bonnefont JP, Rambaud C, Vassault A, Rabier D, et al. Hepatic failure in disorders of oxidative phosphorylation with neonatal onset. J Pediatr. 1991;119:951–954. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohm M, Pronicka E, Karczmarewicz E, Pronicki M, Piekutowska-Abramczuk D, Sykut-Cegielska J, et al. Retrospective, multicentric study of 180 children with cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:21–26. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000190572.68191.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taaman JW. Human cytochrome c oxidase: structure, function, and deficiency. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29:151–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1022638013825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valnot I, Osmond S, Gigarel N, Mehaye B, Amiel J, Cormier-Daire V, et al. Mutations of the SCO1 gene in mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase deficiency with neonatal-onset hepatic failure and encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1104–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62940-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sacconi S, Salviati L, Sue CM, Shanske S, Davidson MM, Bonilla E, et al. Mutation screening in patients with isolated cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:224–230. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000048100.91730.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Lonlay P, Valnot I, Barrientos A, Gorbatyuk M, Tzagoloff A, Taanman JW, et al. A mutant mitochondrial respiratory chain assembly protein causes complex III deficiency in patients with tubulopathy, encephalopathy and liver failure. Nat Genet. 2001;29:57–60. doi: 10.1038/ng706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Meirleir L, Seneca S, Damis E, Sepulchre B, Hoorens A, Gerlo E, et al. Clinical and diagnostic characteristics of complex III deficiency due to mutations in the BCS1L gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;121:126–131. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moraes CT, Shanske S, Tritschler HJ, Aprille JR, Andreetta F, Bonilla E, et al. mtDNA depletion with variable tissue expression: a novel genetic abnormality in mitochondrial diseases. Am J Human Genet. 1991;48:492–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jullig M, Eriksson S. Mitochondrial and submitochondrial localization of human deoxyguanosine kinase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5466–5472. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Munch-Petersen B, Herrstrom Sjoberg A, Hellman U, Bergman T, Jornvall H, et al. Human thymidine kinase 2: molecular cloning and characterisation of the enzyme activity with antiviral and cytostatic nucleoside substrates. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:170–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandel H, Szargel R, Labay V, Elpeleg O, Saada A, Shalata A, et al. The deoxyguanosine kinase gene is mutated in individuals with depleted hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA. Nat Genet. 2001;29:337–341. doi: 10.1038/ng746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saada A, Shaag A, Mandel H, Nevo Y, Eriksson S, Elpeleg O. Mutant mitochondrial thymidine kinase in mitochondrial DNA depletion myopathy. Nat Genet. 2001;29:342–344. doi: 10.1038/ng751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salviati L, Sacconi S, Mancuso M, Otaegui D, Camano P, Marina A, et al. Mitochondrial DNA depletion and dGK gene mutations. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:311–317. doi: 10.1002/ana.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrari G, Lamantea E, Donati A, Filosto M, Briem E, Carrara F, et al. Infantile hepatocerebral syndromes associated with mutations in the mitochondrial DNA polymerase-γA. Brain. 2005;128:723–731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horvath R, Hudson G, Ferrari G, Futterer N, Ahola S, Lamantea E, et al. Phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of the mitochondrial polymerase γ gene. Brain. 2006;129:1674–1684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naviaux RK, Nguyen KV. POLG mutations associated with Alpers’ syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:706–712. doi: 10.1002/ana.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen KV, Sharief FS, Chan SSL, Copeland WC, Naviaux RK. Molecular diagnosis of Alpers syndrome. J Hepatol. 2006;45:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kagumi LS. DNA polymerase γ: the mitochondrial replicase. Ann Rev Biochem. 2004;73:293–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naviaux RK, Nyhan WL, Barshop BA, Poulton J, Markusic D, Karpinski NC, et al. Mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma deficiency and mtDNA depletion in a child with Alpers’ syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:54–58. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<54::aid-art10>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamantea E, Tiranti V, Bordoni A, Toscano A, Bono F, Servidei S, et al. Mutations of mitochondrial DNA polymerase gammaA are a frequent cause of autosomal dominant or recessive progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:211–219. doi: 10.1002/ana.10278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karadimas CL, Vu TH, Holve SA, Chronopoulou P, Quinzii C, Johnsen SD, et al. Navajo neurohepatopathy is caused by a mutation in the MPV17 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:544–548. doi: 10.1086/506913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rotig A, Cormier V, Blanche S, Bonnefont JP, Ledeist F, Romero N, et al. Pearson's marrow-pancreas syndrome. A multisystem mitochondrial disorder in infancy. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1601–1608. doi: 10.1172/JCI114881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sano T, Ban K, Ichiki T, Kobayashi M, Tanaka M, Ohno K, et al. Molecular and genetic analyses of two patients with Pearson's marrow-pancreas syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:105–110. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199307000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobs LJAM, Jongbloed RJE, Wijburg FA, de Klerk JBC, Geraedts JPM, Nijland JG, et al. Pearson syndrome and the role of deletion dimers and duplications in the mtDNA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004;27:47–55. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000016601.49372.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MITOMAP . A human mitochondrial genome database. Center for Molecular Medicine, Emory University; Atlanta, GA.: [March 19, 2007]. Available at: http://www.mitomap.org. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gillis LA, Sokol RJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations of mitochondrial disease. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2003;32:789–817. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frei B, Kim MC, Ames BN. Ubiquinol-10 is an effective lipid-soluble antioxidant at physiological concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4879–4883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sokal EM, Sokol R, Cormier V, Lacaille F, McKiernan PJ, Van Spronsen FJ, et al. Liver transplantation in mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(suppl 2):S81–S84. doi: 10.1007/pl00014328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomson M, McKiernan P, Buckels J, Mayer D, Kelly D. Generalised mitochondrial cytopathy is an absolute contraindication to orthotopic liver transplant in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26:478–481. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dubern B, Broue P, Dubinsson C, Cormier-Daire V, Habes D, Chardot C, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation for mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders: a study of 5 children. Transplantation. 2001;71:633–637. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delarue A, Paut O, Guys J-M, Monfort MF, Lethel V, Roquelaure B, et al. Inappropriate liver transplantation in a child with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome misdiagnosed as valproate-induced acute liver failure. Pediatr Transplant. 2000;4:67–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2000.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinowitz SS, Gelfond D, Chen CK, Gloster ES, Whitington WF, Sacloni S, et al. Hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome. Clinical and morphological features of a nuclear gene mutation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutri. 2004;38:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haas R, Dietrich R. Neuroimaging of mitochondrial disorders. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:471–490. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barragan-Campos HM, Vallee JN, Lo D, Barrera-Ramirez CF, Argote-Greene M, Sanchez-Geurrero J, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients with mitochondrial cytopathies. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:737–742. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. [March 19, 2007];Cholestatic Liver Disease Consortium (CLiC) Available at: http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/clic/index.htm.