Abstract

Background and Purpose

Arterial stiffening is associated with hypertension, stroke, and cognitive decline; however, the effects of aging and cardiovascular disease risk factors on carotid artery stiffening have not been assessed prospectively in a large multi-ethnic, longitudinal study.

Methods

Distensibility coefficient and Young’s elastic modulus of the right common carotid artery were calculated at baseline and after a mean (standard deviation) of 9.4 (0.5) years in 2,650 participants. Effects of age and cardiovascular disease risk factors were evaluated by multivariable mixed regression and analysis of covariance models.

Results

At baseline, participants were 59.9 (9.4) years old (53% female; 25% Black, 22% Hispanic, 14% Chinese). Young’s elastic modulus increased from 1,581 (927) to 1,749 (1,306) mmHg (p<0.0001) and distensibility coefficient decreased from 3.1 (1.3) to 2.7 (1.1) x 10−3 mmHg−1 (p<0.001), indicating progressive arterial stiffening. Young’s elastic modulus increased more among participants who were >75 years old at baseline (p<0.0001). In multivariable analyses, older age and less education independently predicted worsening Young’s elastic modulus and distensibility coefficient. Stopping antihypertensive medication during the study period predicted more severe worsening of Young’s elastic modulus (β=360.2 mmHg, p=0.008). Starting antihypertensive medication after exam 1 was predictive of improvements in distensibility coefficient (β =1.1 x 10−4, mmHg−1; p=0.024).

Conclusions

Arterial stiffening accelerates with advanced age. Older individuals experience greater increases in Young’s elastic modulus than do younger adults, even after considering the effects of traditional risk factors. Treating hypertension may slow the progressive decline in carotid artery distensibility observed with aging and improve cerebrovascular health.

Keywords: Aging, Carotid arteries, Elasticity, Hypertension, Cardiovascular disease risk factors

Introduction

Stroke, cognitive decline and conventional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors have been associated with increased arterial stiffness in cross-sectional analyses;1–4 however, much less is known about the longitudinal relationships between traditional CVD risk factors and changes in arterial dynamics. Increases in arterial stiffness with aging are due to fragmentation of elastin fibers and a decrease in the elastin to collagen ratio in the walls of large arteries.5–7 This process may underlie the development of hypertension and its complications5 as a more rigid arterial tree is less able to accommodate large pulsatile blood volumes. Treatment of systolic blood pressure (SBP) reduces cardiac and cerebral vascular events in elderly populations; however, no longitudinal, observational studies have described the effects of hypertension and treatment of hypertension on progression of local arterial stiffness over a decade.1,8,9

To our knowledge, this is the first large study to evaluate the longitudinal associations between aging, traditional CVD risk factors, and changes in carotid distensibility and elasticity in a diverse cohort without clinically evident CVD.

Methods

Study Participants and Design

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a large prospective, cohort study that is investigating the prevalence, causes, and progression of subclinical CVD. MESA is a population-based sample of 6,814 men and women aged 45 to 84 years, free of known CVD at baseline, recruited from 6 United States communities. The study objectives and design have been published previously.10 All participants gave informed consent for the study protocol, which was approved by the institutional review boards of the ultrasound reading center and all MESA field centers.

The present analyses were pre-specified and include a sub-set of MESA participants with valid carotid distensibility measurements at exam 1 (baseline) and exam 5 who were not missing pertinent exam 1 covariates (n=2650) (Supplement A: Flow diagram). Demographic, medical history, and laboratory data for the present study were obtained from the first (July, 2000 to August, 2002) and fifth (January, 2012 to February, 2012) examinations of the cohort. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL or use of antiglycemic medications. Impaired fasting glucose was defined as blood glucose 100–125 mg/dL. Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were measured after a 12-hour fast. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was calculated. Young’s elastic Modulus (YEM) and carotid distensibility coefficient (DC) were calculated using standard formulae (Supplement B).

B-mode Ultrasound and Brachial Blood Pressure Measurements

At exam 1, B-mode ultrasound video loop recordings of a longitudinal section of the distal right common carotid artery were recorded on videotape using a Logiq 700 ultrasound system (General Electric Medical Systems, transducer frequency 13 MHz). Video images were digitized at high resolution and frame rates using a Medical Digital Recording (MDR) device (PACSGEAR, Pleasanton, CA) and converted into DICOM compatible digital records. At exam 5, a similar protocol was performed using the same ultrasound and digitizing equipment; however, the video output was directly digitized using the same MDR settings without use of videotape. Certified and trained sonographers from all 6 MESA sites used selected reference images from exam 1 to try to match the scanning conditions of the initial study, including common carotid artery display depth, angle of approach, surrounding tissues and internal landmarks, degree of jugular venous distension, and ultrasound system settings. After 10 minutes of rest in the supine position and immediately before the ultrasound image acquisition, repeated measures of brachial blood pressures were obtained using a standardized protocol with an automated upper arm sphygmomanometer (DINAMAP, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Ultrasound images were reviewed and interpreted by the MESA Carotid Ultrasound Reading Center (the University of Wisconsin Atherosclerosis Imaging Research Program, Madison, WI). Systolic and diastolic diameters were determined as the largest and smallest diameters during the cardiac cycle. All measurements were made manually and performed in triplicate from 2–3 consecutive cardiac cycles. Internal and external artery diameters were measured using Access Point Web version 3.0 (Freeland Systems, LLC, Westminster, CO). Measurement reproducibility was excellent (Supplement C).

Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. Paired t-tests were used to compare baseline and exam 5 continuous characteristics. McNemar’s test and Bhapkar’s test were used for dichotomous and multi-category variables, respectively. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess ethnic differences in continuous variables and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables.

A repeated measures mixed model, adjusted for risk factors, was used to estimate mean YEM and DC at baseline and at exam 5 as well as their changes between baseline and exam 5. Baseline age was classified into four decades (ages 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84 years). Age and study exam were specified as class variables and the interaction of exam*age group was included in the models to allow evaluation of whether the differences between exams differed by age.

Differences between baseline and exam 5 measures were examined using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for risk factors, with and without adjustment for baseline stiffness measures to account for the fact that in subjects with high levels of stiffness at baseline, the independent variables may have less of an effect on progression of YEM and DC, which are referred to as ceiling effects for YEM or floor effects for DC. Since the results of both models were similar the adjusted data are presented. The models that were not adjusted for baseline are in Supplementary Tables I and II. Sequential ANCOVA models were performed as unadjusted; adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, study site; baseline CVD risk factors (body-mass index [BMI], diabetes mellitus status, SBP, use of antihypertensive medication, lipids, use of lipid-lowering medications, physical activity, and smoking status); and then adjusted for antihypertensive medication use at exam 1 and exam 5. All analyses were carried out with the use of SAS (Version 9.3, Cary, NC: SAS. Institute Inc.).

Results

Participant Characteristics

At baseline, participants were a mean (standard deviation) of 59.9 (9.4) years old, 53% were female, 39% were White, 25% Black, 22% Hispanic, and 14% were Chinese. Most participants (68.9%), graduated from high school, 17.2% had some high school education and 13.8% had no high school education. The mean follow-up was 9.5 (0.5) years. Baseline and exam 5 characteristics including the prevalence of CVD risk factors are shown in Table 1. Pulse pressure, carotid wall thickness, and arterial diameter increased with age (all p<0.0001) and were greatest in the oldest age group. Older subjects had greater increases in end-diastolic internal diameter (75–84 years: 0.020 cm; 65–74 years: 0.022 cm; 55–64 years: 0.019 cm; 45–54 years: 0.017 cm; p=0.02) but less wall thickening (75–84 years: 0.011 cm; 65–74 years: 0.014 cm; 55–64 years: 0.016 cm; 45–54 years: 0.018 cm; p<0.0001) compared to younger subjects.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline and Exam 5

| N=2650 | Baseline | Exam 5 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.9 (9.4) | 69.3 (9.3) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex (%) | 1414 (53.4) | NA | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| White | 1039 (39.2) | NA | |

| Black | 660 (24.9) | ||

| Chinese | 380 (14.3) | ||

| Hispanic | 571 (21.6) | ||

| Blood pressure parameters (mmHg) | |||

| SBP | 123.3 (20.0) | 123.6 (20.5) | 0.42 |

| DBP | 71.7 (10.1) | 68.4 (10.2) | <0.0001 |

| Pulse pressure | 51.6 (15.6) | 55.3 (17.3) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1118 (42.2) | 1596 (60.3) | <0.0001 |

| HTN meds (%) | 864 (32.6) | 1390 (52.5) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus status (%) | |||

| IFG | 317 (12.0) | 557 (21.1) | <0.0001 |

| Untreated | 42 (1.6) | 41 (1.6) | |

| Treated | 181 (6.8) | 420 (15.9) | |

| Lipids (mg/dL) | |||

| Total cholesterol | 194.1 (34.9) | 183.7 (36.7) | <0.0001 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 117.2 (30.5) | 105.9 (32.0) | <0.0001 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 51.5 (15.1) | 56.5 (17.2) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides | 127.7 (81.7) | 107.9 (60.7) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid-lowering meds (%) | 400 (15.1) | 993 (37.5) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 (5.0) | 27.9 (5.3) | <0.0001 |

| Waist (cm) | 96.2 (13.7) | 97.8 (13.7) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking (%) | |||

| Former | 940 (35.5) | 1205 (45.7) | |

| Current | 297 (11.2) | 194 (7.4) | <0.0001 |

| YEM (mmHg) | 1581 (927) | 1749 (1306) | <0.0001 |

| DC (10−3 mmHg−1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Carotid wall thickness (cm) | 0.147 (0.030) | 0.163 (0.033) | <0.0001 |

| PSI Diameter (cm) | 0.627 (0.074) | 0.644 (0.080) | <0.0001 |

| EDI Diameter (cm) | 0.581 (0.070) | 0.599 (0.076) | <0.0001 |

NA = not applicable, SBP = Systolic blood pressure, DBP = Diastolic blood pressure, HTN = hypertension, meds = medication, IFG = Impaired fasting glucose, BMI = Body mass index, YEM = Young’s elastic modulus, DC = Distensibility coefficient, PSI = peak-systolic internal, EDI = end-diastolic internal diameter

All values are mean (standard deviation) unless noted otherwise. P-values for continuous variables are from paired t-tests and for categorical variables from McNemar’s or Bhapkar’s tests.

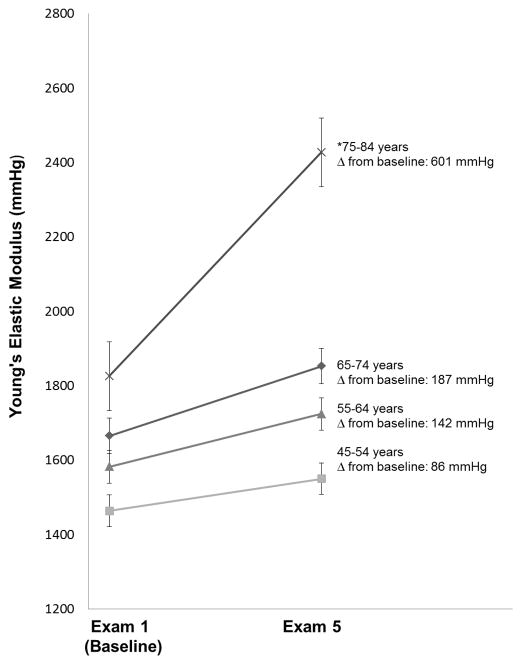

Young’s Elastic Modulus

Mean YEM increased from 1,581 (927) to 1,749 (1,306) mmHg (p<0.0001) over the study period, indicating progressive arterial stiffening. YEM increased significantly more among older participants and was especially prominent in those >75 years old at baseline, indicating an accelerated rate of arterial stiffening in this group (p<0.0001, Figure 1). Older age independently predicted an accelerated increase in YEM from exam 1 to exam 5 (p<0.0001). Use of antihypertensive medications at baseline predicted more of an accelerated rate of increase in YEM; higher education level predicted slower progression of YEM (Table 2). Other traditional CVD risk factors including lipid levels, diabetes mellitus status, BMI and smoking status were not independent predictors of change in YEM (all p values >0.05).

Figure 1. Change in Young’s Elastic Modulus from Baseline to Exam 5.

*p<0.0001 for change from baseline compared to all other age groups

Table 2.

Multivariate ANCOVA Regression Models for Change in Young’s Elastic Modulus*

| Significant predictors | β | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Model 1 R2=0.148 |

Age | 16.5 | <0.0001 |

| Education level (compared to those who did not graduate high school) | |||

| High school graduate | −235.8 | 0.007 | |

| Greater than high school | −243.1 | 0.003 | |

| Use of antihypertensive medication at baseline | 175.8 | 0.001 | |

|

| |||

|

Model 2 R2=0.150 |

Age | 16.8 | <0.001 |

| Education level (compared to those who did not graduate high school) | |||

| High school graduate | −236.4 | 0.007 | |

| Greater than high school | −243.0 | 0.003 | |

| Former smoker at baseline | −101.1 | 0.050 | |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (per mmHg) | 2.8 | 0.043 | |

| Stopping antihypertensive medication | 360.2 | 0.008 | |

Models shown are adjusted for baseline YEM

Model 1: Age, sex, race, study site, socioeconomic factors (education level, income) and traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors (systolic blood pressure, diabetes status, smoking status, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, body-mass index, and physical activity level) and treatment of traditional cardiovascular risk factors at baseline (use of antihypertensive medications, use of lipid lowering medications)

Model 2: Model 1 + exchanging the variable use of antihypertensive medication at baseline with 4 categories: 1) never treated with antihypertensive medication (untreated at exam 1 and exam 5), the reference group; 2) continued use of antihypertensive medication (treated at exam 1 and treated at exam 5); 3) starting antihypertensive medication (untreated at Exam 1, treated at exam 5); and 4) stopping antihypertensive medications (treated at exam 1, untreated at exam 5).

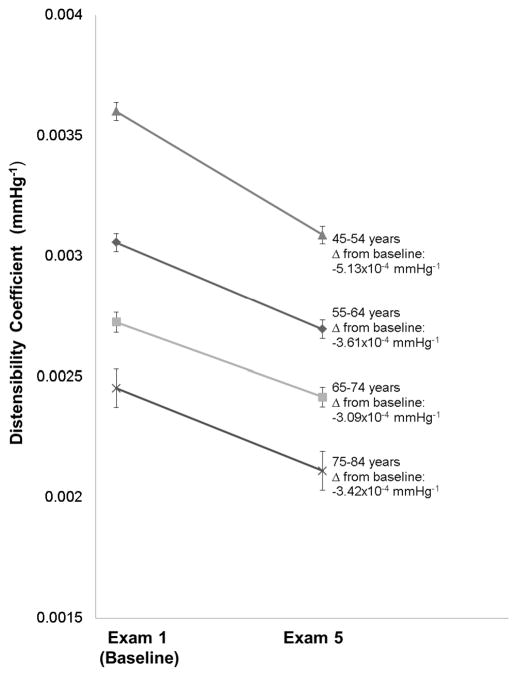

Distensibility Coefficient

Mean DC decreased from 3.1 (1.3) to 2.7 (1.1) 10−3 mmHg−1 (p<0.001), also indicating progressive arterial stiffening (Table 1). Older age was an independent predictor of worsening DC (p<0.0001), even after adjustment of socioeconomic factors and CVD risk factors (Table 3). However, the magnitude of DC changes between participants in the oldest and younger age groups were similar (all p>0.05, Figure 2). Chinese ethnicity, treated diabetes mellitus, and higher SBP also were independent predictors of an accelerated decrease in DC. As with YEM, higher education level independently predicted a higher DC corresponding to more compliant arteries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate ANCOVA Regression Models for Change in Distensibility Coefficient*

| Significant predictors | β | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Model 1 R2 = 0.359 |

Age | −2.2x10−5 | <0.0001 |

| Chinese Race | −1.9x10−4 | 0.006 | |

| Study site | |||

| University of Minnesota | 3.1x10−4 | <0.0001 | |

| University of California – Los Angeles | 1.6x10−4 | 0.025 | |

| Education level (compared to those who did not graduate high school) | |||

| Greater than high school | 1.7x10−4 | 0.006 | |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (per mmHg) | −2.8x10−6 | 0.007 | |

| Treated diabetes at baseline | −1.6x10−4 | 0.029 | |

|

| |||

|

Model 2 R2 = 0.361 |

Age | −2.2x10−5 | <0.0001 |

| Chinese race | −1.9x10−4 | 0.006 | |

| Study site | |||

| University of Minnesota | 3.1x10−4 | <0.0001 | |

| Education level (compared to those who did not graduate high school) | |||

| Greater than high school | 1.7x10−4 | 0.007 | |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (per mmHg) | −3.6x10−6 | 0.001 | |

| Starting antihypertensive medication | 1.1x10−4 | 0.024 | |

| Treated diabetes mellitus at baseline | −1.8x10−4 | 0.018 | |

Models shown are adjusted for baseline DC

Model covariates are the same as in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Change in Distensibility Coefficient from Baseline to Exam 5

Associations with CVD Risk Factors

As in Table 1, there were significant increases in BMI, waist circumference, rates of diabetes mellitus, and the percentage of participants on lipid-lowering and antihypertensive therapies from exam 1 to exam 5 (all p<0.0001). Sex was not a significant predictor of change in YEM or DC. Menopausal status did not predict changes in DC or YEM in analyses restricted to women.

Use of antihypertensive medication at baseline was independently associated with an increase in YEM. Higher baseline SBP predicted worsening DC. To further explore relationships between medication use, blood pressure, and arterial stiffness, models were created that evaluated changes in use of antihypertensive therapy from exam 1 to exam 5. Stopping antihypertensive medication was a strong independent predictor of accelerating YEM (p=0.008), though only 84 participants (3.1%) stopped antihypertensive medications between exams 1 and 5. After adding exam 5 treatment to the model, SBP (p=0.043) and being a former smoker (p=0.049) predicted changes in YEM (Table 2). For DC, starting on antihypertensive therapy independently predicted an improvement in DC (p=0.024) after adjusting for baseline DC. Similar findings with regard to changes in YEM and DC were detected in sensitivity analyses that included antihypertensive medication treatment at MESA exams 2, 3, and 4 (data not shown). Follow-up time was not an independent predictor of change in YEM. For DC, follow-up time was an independent predictor (β= −1.2x10−4 mmHg−1, p=0.004); however, its addition to the models did not change the magnitude of the associations or level of significance of the other variables (data not shown).

Differences in DC and YEM by Ethnicity

Differences among ethnic groups at baseline and exam 5 are shown in Supplementary Table III. Baseline YEM was significantly higher (worse) in Black (1,630 [1023] mmHg), Chinese (1,733 [996] mmHg), and Hispanic (1,687 [908] mmHg) participants as compared to White participants (1,436 [823] mmHg) (all p<0.0001). Baseline DC was higher (better) in White participants compared to other ethnicities (p<0.0001). Age was similar across ethnic groups (p=0.359). Black participants had higher baseline and exam 5 systolic and diastolic blood pressures compared with other groups (p<0.0001). Hispanic participants had higher blood pressures than White and Chinese participants (all p<0.05); however, average systolic and diastolic blood pressures of all ethnic groups were not in the hypertensive range. All ethnic groups progressively stiffened at a similar rate with no significant differences in change in YEM (p=0.246) or DC (p=0.233) from exam 1 to 5.

At baseline, non-white ethnic groups started with stiffer arteries (YEM and DC); however, in the repeated measures models, only White (P=0.002) and Black (p=0.01) participants exhibited a significant age group*exam interaction. The change in YEM in the oldest Hispanic and Chinese participants was not statistically significantly different from the younger age groups (all p≥0.07, Supplement Figure I). Change in DC was not significantly different between participants in the oldest age group compared to younger participants in any ethnic group (all p≥0.2; Supplement Figure II).

Discussion

Although cross-sectional studies have demonstrated higher arterial stiffness with increasing age,2,5,6 longitudinal changes in arterial stiffness over nearly a decade of aging have not been described in a large, multi-ethnic population. The values obtained for YEM and DC are similar to those that have been reported elsewhere.2,6 Previous longitudinal studies that evaluated changes in carotid artery stiffness parameters were small,11 of short duration,11–14 and/or were performed in younger, more homogeneous populations.12–14 Our study confirms a strong, cross-sectional association between older age and arterial stiffness, but also identified a longitudinal increase in arterial stiffness that was especially prominent in older participants. Importantly, more rapid stiffening (increased YEM) was observed among the oldest participants, and for participants that discontinued antihypertensive medication. Lower baseline SBP and longitudinal use of antihypertensive medications were associated with slower progression of arterial stiffness. Reduced carotid arterial stiffness could translate into reduced risk for stroke and cognitive dysfunction, since stiffer arteries do not dampen pulse wave transmissions which may amplify more deeply towards cerebral capillaries.7

Our data suggest that the pathophysiological processes that underlie progressive arterial stiffening do not evolve linearly. YEM, but not DC, increased most rapidly in the oldest participants. Older individuals had a disproportionate increase in arterial diameter relative to wall thickness. YEM detected adverse arterial remodeling with aging because it accounts for wall thickness, whereas change in DC among older participants appeared to be blunted due to floor effects; those who started with the stiffest arteries (lowest DC) had less physiologic “room” for change and ultimately less progression of DC since they had larger arterial diameters and wider pulse pressures at baseline.

Prior cross-sectional analysis of distensibility measures in the MESA cohort found associations with traditional CVD risk factors including sex, ethnicity, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and lipid levels, but not treatment of hypertension.2,3 Socio-economic status and health care access have also been associated with CVD risk in MESA.15 Baseline YEM and DC were significantly worse in non-white participants but progression rates did not differ by race. Racial differences in the prevalence of hypertension may explain this observation, at least in part. Also, ethnicity was an independent predictor of change in DC, but not for change in YEM. The major difference between the stiffness parameters used in this study is that YEM includes wall thickness weighted for end-diastolic diameter. Wall thickness had highly significant associations (P<0.0001) with YEM and DC, but when it was included in the models for YEM and DC (not shown), it had little effect, suggesting that the effect of differences in wall thickness between ethnic groups is minimal. Regardless, the oldest participants in all ethnic groups showed a pronounced increase in YEM over time, though it was most prominent in Black and White participants after adding an age*exam interaction term.

Hypertension and its treatment seem to play a greater role in the progression of arterial stiffness over 10 years. Starting or stopping antihypertensive medications between exams 1 and 5 was associated with changes in arterial distensibility, suggesting that examining the effects of treatment of blood pressure at a single time point is inadequate to explain these complex relationships. Our data also suggest that continuing to treat hypertension retards adverse changes in arterial stiffness, especially in the older individuals. Clinicians often hesitate to treat hypertension in elderly patients due to concerns for adverse events, despite the fact that treatment has been shown to reduce risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, CVD death, and all-cause mortality.16,17 Use of antihypertensive medications in older patients may reduce clinical events by slowing the progressive arterial stiffness that accompanies aging and its resulting end-organ damage. Arterial stiffening also is associated with cognitive decline and may be a target for reducing dementia by improving cerebrovascular health.1,4

Limitations

The reported associations cannot confirm causation; longitudinal follow-up from clinical trials of antihypertensive therapy are needed to confirm the effects of therapy we observed. Our participants were a subset of the MESA study; there may be a bias based on survival to exam 5. Those who participated in exam 5 were healthier and less likely to have a non-fatal CVD event than the original MESA cohort; however, this would create a null bias. Brachial artery blood pressures were considered as surrogates for carotid arterial pressures. Although a standard practice in epidemiological studies, brachial measurements can overestimate central pressures, though this difference is smaller in older participants and would amplify the null bias.18,19 SBP may confound our analyses since it was used to generate the blood pressures used in the YEM and DC equations.

Conclusions

Carotid arterial stiffening accelerates with advanced age. Older individuals experience greater increases in YEM than do younger adults, even after considering the effects of traditional CVD risk factors. Baseline YEM and DC were significantly worse in non-white participants but progression rates did not differ by ethnicity. Higher baseline blood pressure predicted increases in arterial stiffness over a decade. Stopping antihypertensive therapy was associated with increased arterial stiffening; longitudinal use of antihypertensive medications slowed its progression, especially in elderly participants. Treatment of hypertension retards the progressive decline in carotid artery distensibility observed with aging. These findings support treatment of hypertension in older adults and may provide a new target for improving cerebrovascular health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Funding Sources

Supported by contracts HC95159-HC95169 and HL07936 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, grant ES015915 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and grants RR024156 and RR025005 from the National Center for Research Resources. This publication was developed under Science to Achieve Results research assistance agreement RD831697 from the Environmental Protection Agency. It has not been formally reviewed by the Environmental Protection Agency. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors. The Environmental Protection Agency does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication. Adam Gepner was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center (T32HL07936). Elizabeth Hom was supported by the University of Washington “Biostatistics, Epidemiologic and Bioinformatic Training in Environmental Health Training Grant,” which is sponsored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES015459).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Stein: Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation

Reference List

- 1.Yang EY, Chambless L, Sharrett AR, Virani SS, Liu X, Tang Z, et al. Carotid arterial wall characteristics are associated with incident ischemic stroke but not coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2012;43:103–108. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaidya D, Heckbert SR, Wasserman BA, Ouyang P. Sex-specific association of age with carotid artery distensibility: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:516–520. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharrett AR, Ding J, Criqui MH, Saad MF, Liu K, Polak JF, et al. Smoking, diabetes, and blood cholesterol differ in their associations with subclinical atherosclerosis: the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeki AH, Newman AB, Simonsick E, Sink KM, Sutton TK, Watson N, et al. Pulse wave velocity and cognitive decline in elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Stroke. 2013;44:388–393. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.673533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safar ME. Systolic hypertension in the elderly: arterial wall mechanical properties and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Hypertens. 2005;23:673–681. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000163130.39149.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Rourke MF, Staessen JA, Vlachopoulos C, Duprez D, Plante GE. Clinical applications of arterial stiffness; definitions and reference values. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:426–444. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reneman RS, Meinders JM, Hoeks AP. Non-invasive ultrasound in arterial wall dynamics in humans: what have we learned and what remains to be solved. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:960–966. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijk RA, Nijpels G, Twisk JW, Steyn M, Dekker JM, Heine RJ, et al. Change in common carotid artery diameter, distensibility and compliance in subjects with a recent history of impaired glucose tolerance: a 3-year follow-up study. J Hypertens. 2000;18:293–300. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koskinen J, Magnussen CG, Viikari JS, Kahonen M, Laitinen T, Hutri-Kahonen N, et al. Effect of age, gender and cardiovascular risk factors on carotid distensibility during 6-year follow-up. The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira I, Beijers HJ, Schouten F, Smulders YM, Twisk JW, Stehouwer CD. Clustering of metabolic syndrome traits is associated with maladaptive carotid remodeling and stiffening: a 6-year longitudinal study. Hypertension. 2012;60:542–549. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koskinen J, Magnussen CG, Taittonen L, Rasanen L, Mikkila V, Laitinen T, et al. Arterial structure and function after recovery from the metabolic syndrome: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2010;121:392–400. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen NB, Diez-Roux A, Liu K, Bertoni AG, Szklo M, Daviglus M. Association of health professional shortage areas and cardiovascular risk factor prevalence, awareness, and control in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:565–572. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.960922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA. 2005;294:466–472. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD000028. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson IB, Franklin SS, Hall IR, Tyrrell S, Cockcroft JR. Pressure amplification explains why pulse pressure is unrelated to risk in young subjects. Hypertension. 2001;38:1461–1466. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.