Abstract

We report a case of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related postliver transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) in a patient with post liver transplant which initially presented in a CT scan image mimicking recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Histopathology showed atypical plasma cell-like infiltration, and immunohistochemistry confirmed diagnosis of EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Typical imaging from dynamic phases contrast CT scan might not accurately diagnose recurrent HCC in postorthotropic liver transplantation. Liver biopsy should be performed for accurate diagnosis and proper treatment.

Background

Post-transplantation achieving adequate control of the immune response to the allograft from immunosuppressive drugs has led to improved patient and graft survival related to rejection. However, susceptibility to infections in the post-transplant period was increased.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is an important pathogen in recipients of solid organ transplants (SOT). Infection with EBV manifests as a spectrum of diseases/malignancies ranging from asymptomatic viremia through infectious mononucleosis to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD).1 After host was infected with EBV, the virus EBV directly infects resting B cells or infects epithelial cells. After convalescence, EBV is present in the peripheral blood in latently infected memory B cells and infects the host's B lymphocytes establishing a reservoir of latent virus.2 Not only EBV load but also low concomitant cellular immune responses are indicative of the PTLD risk in transplant recipients.3

Cumulative 5-year incidence of PTLD in liver transplant recipients was reported to be 5% in paediatric patients and 1% in adult patients.4

Case presentation

We report a case of PTLD in patients with liver transplant with initially presenting CT scan mimicking recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

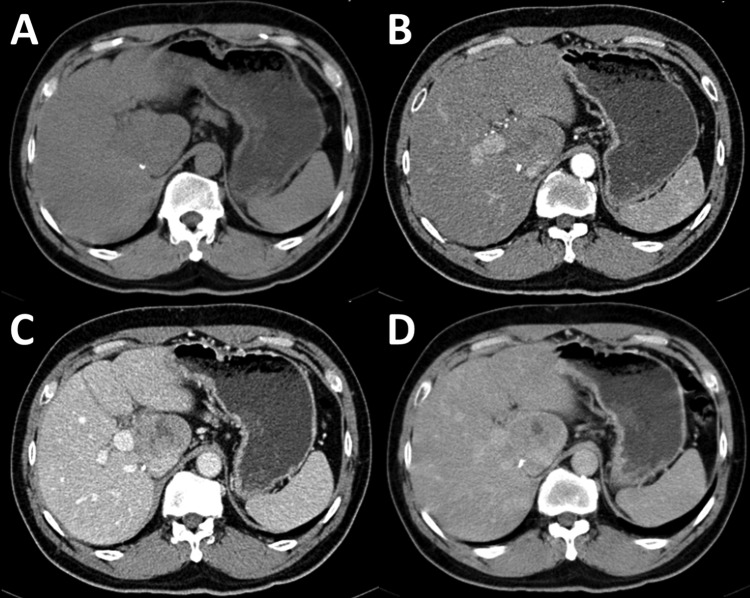

A 50-year-old Thai male patient, post orthotopic liver transplantation for 7 months from hepatitis B cirrhosis with hepatocellular carcinoma, presented to the liver transplant clinic for regular follow-up. He recently had elevation of aminotransferase up to 188 U/L. There was no history of alcohol drinking or any other non-prescribed drugs. His recent medication included prograft 4 mg/day, cellcept 500 mg/day, prednisolone 10 mg/day, adefovir 10 mg/day and lamivudine 100 mg/day. After complete evaluation of serological test, no causes of hepatitis were found (table 1). Ultrasonography of upper abdomen was performed routinely before liver biopsy. Ultrasound finding was a newly seen 3.9×2.6×4 cm heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion, possibly to be exophytic mass from caudate lobe. CT upper abdomen was then performed for evaluating this mass lesion. CT finding showed 4.6×3.2 cm exophytic mass from caudate lobe with central necrosis, showing slightly arterial enhancing and washout on portovenous phase (figure 1). No significant enlarged intra-abdominal lymph node was seen. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma was suspected.

Table 1.

Results of immunological and virological laboratory tests

| Laboratory tests | Results |

|---|---|

| HBsAg | Negative |

| Anti-HBs | Negative |

| Anti-HSV IgM | Negative |

| Anti-HSV IgG | Positive |

| Anti-HEV IgM | Negative |

| Anti-HEV IgG | Negative |

| Anti-EBV IgM | Negative |

| Anti-EBV IgG | Positive |

| HBV DNA(IU/mL) | <10 |

| HCV RNA(IU/mL) | <12 |

| CMV viral load(IU/mL) | <20 |

| EBV viral load(IU/mL) | <600 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, HBV surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HEV HSV, herpes simplex virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

Figure 1.

Dynamic phases CT scan of upper abdomen show 4.6×3.2 cm exophytic mass from caudate lobe with central area of necrosis (A). This lesion had slightly arterial enhancing (B) and washout on portovenous phase (C). During delay phase (5 min), peripheral enhancement was observed (D).

Investigations

Laboratory data of liver function showed elevation of serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, however, serum tumour markers that included α-Fetoprotein, carbohydrate antigen (CA)19 -9 and carcinoembryonic antigen were in normal range (table 2).

Table 2.

Results of haematological and serum chemical laboratory tests

| Laboratory data | Previous visit (1 month before this visit) | This visit | Before liver biopsy (2 weeks after visit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin, total (mg/dL) | 0.67 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| Bilirubin, direct (mg/dL) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.44 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.1 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 33 | 88 | 97 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 78 | 188 | 222 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 69 | 113 | 152 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 461 | ||

| α-Fetoprotein (IU/mL) | 1.48 | ||

| CA19-9 (IU/mL) | 0.83 | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.85 |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

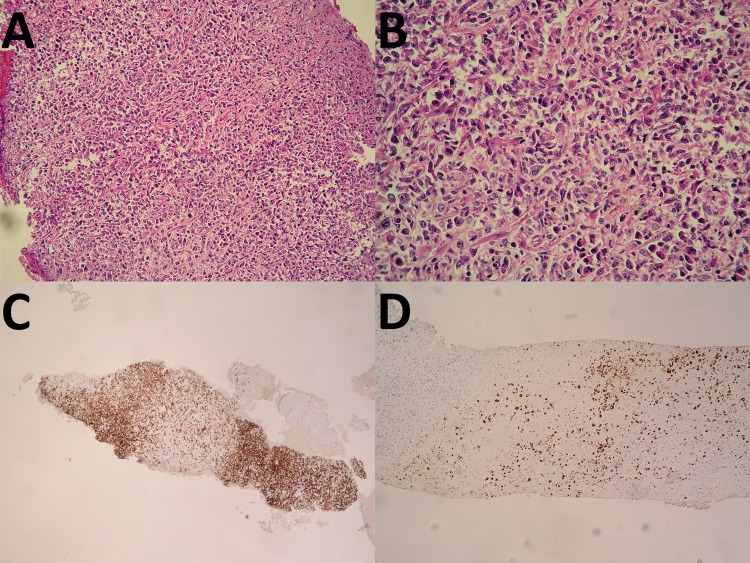

Liver and exophytic mass biopsy were performed. Liver biopsy from left lobe liver demonstrated mild steatosis (20%) without evidence of malignancy or rejection. Histopathology of mass at caudate lobe showed necrotic tissue with atypical plasma cell-like infiltration. Diagnosis of EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation, compatible with monomorphic PTLD was established after the immunohistochemistry (figure 2). The EBV serological status of patient was positive for anti-EBV IgG and negative for anti-EBV IgM previous to the liver transplant; however, we did not have EBV serological status of donor.

Figure 2.

Histopathology of mass at caudate lobe show necrotic tissue with atypical plasma cell-like infiltration (A and B). Immunohistochemistry show CD3: negative, CD20: positive, (C) Ki67: 30–40% positive, CD79a: positive, CD23: negative, CyclinD1: negative, CD10: negative, Bcl-6: negative, MUM1: positive, BCL2: positive, EBV (LMP): positive (D), HHV8: negative and EBER: positive. B-cell lymphoma-6; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; EBV, Epstien-Barr virus; HHV8, human herpes virus 8; MUM1, multiple myeloma oncogene 1; EBER, EBV-encoded RNA.

Treatment

After PTLD was diagnosed, reduction of immune suppression was performed and patient was treated with 700 mg (375 mg/m2) of intravenous rituximab weekly for 4 weeks by the haematologist. Despite treatments, the disease response was stable.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was further treated with rituximab plus chemotherapy, including cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone for eight cycles with partial response to tumour. The patient was scheduled for further external radiation.

Discussion

In a country with high endemic of chronic hepatitis B, HCC is the main cancer in solid organ recipients and PTLD the second most common cancer.5 Most of the patients liver transplant with a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma present with a large hypovascular periportal mass.6

Reduction or cessation of immune suppression has been effectively used as a first-line approach to manage EBV/PTLD for several decades, but this strategy appears to fail in some proportions of patients with PTLD either due to tumour unresponsiveness or significant rejection.7 The majority of patients in whom this strategy will succeed demonstrate some evidence of clinical response within 2–4 weeks of reduction of immune suppression.1

Antiviral treatment of EBV/PTLD with acyclovir has been previously reported.8 Although acyclovir and gancyclovir inhibit EBV DNA replication in vitro, the efficacy of these agents has not been well established and their role in the treatment of EBV/PTLD has been questioned.

Efficacy of humanised, chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab, has been reported to be more than 40% response rate in adults with PTLD who did not respond to reduced immunosuppression.9 Recent data showed significantly improved overall survival associated with reduction of immunosuppression and early rituximab-based treatment in PTLD.10

Learning points.

In a country with high endemic of chronic hepatitis B, HCC is the main cancer in solid organ recipients and PTLD the second most common cancer.

Typical imaging from dynamic phases contrast CT scan might not accurately diagnose recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in post orthotropic liver transplantation.

Liver biopsy is necessary in these types of cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the entire staff of the Gastroenterology Unit of Medicine, Liver Transplant Unit, Department of Radiology and Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University and Hospital, Thai Red Cross Society.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the collection of the data, revision of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Green M, Michaels MG. Epstein-barr virus infection and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Transplant 2013;13(Suppl 3):41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med 2000;343:481–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smets F, Latinne D, Bazin H, et al. Ratio between Epstein-Barr viral load and anti-Epstein-Barr virus specific T-cell response as a predictive marker of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease. Transplantation 2002;73:1603–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2010 data report. Am J Transplant 2012;12(Suppl 1):1–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang YJ, Chen CH, Wu CT, et al. De novo cancer occurrence after renal transplantation: a medical center experience in Taiwan. Transplant Proc 2004;36:2150–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valls C, Ruiz S, Martinez L, et al. Enlarged lymph nodes in the upper abdomen after liver transplantation: imaging features and clinical significance. Radiol Med 2011;116:1067–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen U, Preiksaitis J. Epstein-Barr virus and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009;9(Suppl 4):S87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanto DW, Frizzera G, Gajl-Peczalska KJ, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell lymphoma after renal transplantation: acyclovir therapy and transition from polyclonal to monoclonal B-cell proliferation. N Engl J Med 1982;306:913–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choquet S, Leblond V, Herbrecht R, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in B-cell post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: results of a prospective multicenter phase 2 study. Blood 2006;107:3053–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evens AM, David KA, Helenowski I, et al. Multicenter analysis of 80 solid organ transplantation recipients with post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease: outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1038–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]