Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol (CZP) after 24 weeks in RAPID-axSpA (NCT01087762), an ongoing Phase 3 trial in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), including patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA).

Methods

Patients with active axSpA were randomised 1:1:1 to placebo, CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or CZP 400 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W). In total 325 patients were randomised. Primary endpoint was ASAS20 (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 20) response at week 12. Secondary outcomes included change from baseline in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) linear.

Results

Baseline disease activity was similar between AS and nr-axSpA. At week 12, ASAS20 response rates were significantly higher in CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W arms versus placebo (57.7 and 63.6 vs 38.3, p≤0.004). At week 24, combined CZP arms showed significant (p<0.001) differences in change from baseline versus placebo in BASFI (−2.28 vs −0.40), BASDAI (−3.05 vs −1.05), and BASMI (−0.52 vs −0.07). Improvements were observed as early as week 1. Similar improvements were reported with CZP versus placebo in both AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations. Adverse events were reported in 70.4% vs 62.6%, and serious adverse events in 4.7% vs 4.7% of All CZP versus placebo groups. No deaths or malignancies were reported.

Conclusions

CZP rapidly reduced the signs and symptoms of axSpA, with no new safety signals observed compared to the safety profile of CZP in RA. Similar improvements were observed across CZP dosing regimens, and in AS and nr-axSpA patients.

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a member of the group of chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases known collectively as spondyloarthritis (SpA). It is primarily characterised by inflammation of the sacroiliac (SI) joints and spine, resulting in chronic back pain and reduced function and quality of life. Over time, some patients with axSpA may develop new bone formation in the SI joints and spine (syndesmophytes), causing permanent impairment in spinal mobility and further worsening of function.1 Although axSpA encompasses a broad spectrum of disease, ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is the commonly recognised phenotypic disease, requiring radiographic changes in the SI joints according to the modified New York (mNY) criteria.2 Until recently, axSpA patients without radiographic sacroiliitis, but with evidence of sacroiliitis from MRI or other characteristics of disease, have been less well recognised despite sharing the same common features, such as spinal inflammation, chronic back pain, positivity for human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 and extra-articular manifestations. This latter population, classified as non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA), is covered by the new Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria on axial SpA, together with AS (which has also been termed radiographic axSpA).3 4 The criteria have been developed, in addition to a diagnostic algorithm,5 to facilitate earlier recognition of axSpA, and identify axSpA patients with and without radiographic sacroiliitis,6 7 using X-rays and MRI.3 4 Progression from nr-axSpA to AS, when it occurs, can happen >10 years from the onset of symptoms that typically appear in the second or third decade of life.8–10 Nevertheless, despite evidence of similar burden of disease in AS and nr-axSpA 11–14 delays in the diagnosis of axSpA can postpone administration of suitable treatment by several years.8 9

Under current ASAS/The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are the first-line treatment option for axSpA patients.15 In patients with inadequate response to ≥2 NSAIDs for ≥4 weeks in total, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor therapy is recommended for AS patients.14 16–22 Recent demonstration of efficacy in nr-axSpA has led to ASAS recommendations for the extension of TNF inhibitor treatment to this subpopulation.11 22–25 Indirect evidence and a small direct comparison study26 has suggested similar efficacy in AS and nr-axSpA.

RAPID-axSpA is the first randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial to examine the efficacy of a TNF inhibitor across the spectrum of patients with active axSpA, allowing for a direct comparison of the burden of disease and efficacy of treatment in AS and nr-axSpA patients, as defined by ASAS criteria.3 This report presents the clinical efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol (CZP), a PEGylated Fc-free anti-TNF, up to week 24. In the same issue of the journal, the results of the RAPID-PsA study are presented which report the safety and efficacy of CZP in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).27 28

Methods

Patients

The study group consisted of 325 patients aged ≥18 years with chronic back pain of ≥3 months, fulfilling the ASAS criteria for axSpA.3 All recruited patients had to have active disease, defined by: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)≥4, and spinal pain ≥4 (on a 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)). Additionally, patients had to have C-reactive protein (CRP) levels >upper limit of normal (ULN=7.9 mg/L) and/or sacroiliitis on MRI according to the ASAS/OMERACT definition.3 Eligible patients must have previously had an inadequate response, or been intolerant, to ≥1 NSAID during ≥30 days of continuous therapy (highest tolerated dose) or ≥2 weeks each for ≥2 NSAIDs. Per protocol ≤40% of patients could have had TNF inhibitor >3 months prior to baseline (>28 days for etanercept) if they had discontinued for reasons other than primary failure (eg, secondary failure). Patients with a history of chronic or recurrent infections, serious or life-threatening infection (<6 months prior to baseline, including herpes zoster), or active/high risk of tuberculosis, hepatitis B/C or HIV were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they had been previously exposed to CZP or >2 other biological agents (>1 TNF inhibitor), or had experienced primary failure of a prior TNF inhibitor. AxSpA disease severity related exclusions included diagnosis of total spinal ankylosis (‘bamboo spine’).

Study design

The ongoing 204-week RAPID-axSpA trial (NCT01087762) is a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study conducted at 83 centres in Europe, North America and Latin America. The trial was placebo-controlled to week 24, dose-blind to week 48 and is open label to week 204. The first patient was enrolled in March 2010, and the last patient completed the 24 week period in October 2011. The study was approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board at participating sites, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before any protocol-specific procedures were performed.

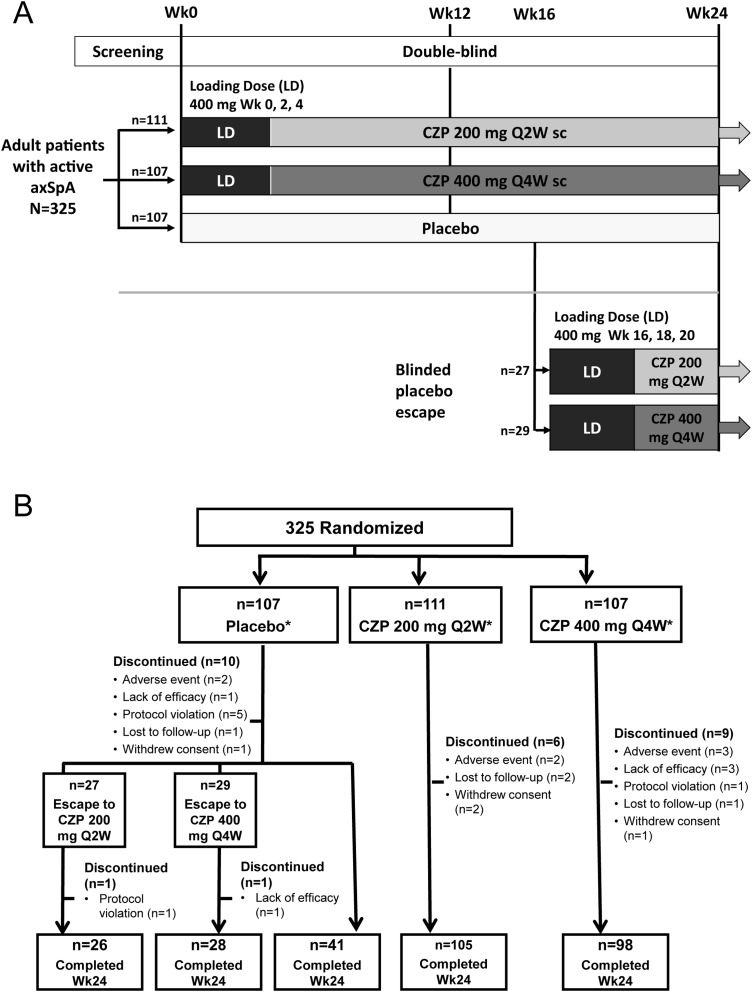

All patients had to fulfil the ASAS axSpA criteria. In order to recruit a broadly balanced population of AS and nr-axSpA patients, at least 50% had to satisfy mNY criteria in addition to ASAS criteria.2 Local X-ray assessment (X-rays of the SI joints prior to screening performed locally by rheumatologists or radiologists) was used for determination of sacroiliitis, and these readings were used to define the subpopulations of AS and nr-axSpA patients in this trial. A baseline X-ray (central assessment) was later added to the trial to allow for subsequent analysis of progression. These X-rays were read centrally in a two-reader approach with adjudication in case of a discrepant scoring. For patients who did not fulfil mNY criteria due to lack of evidence of sacroiliitis on X-ray, ≥50% were recruited based on ASAS MRI imaging criteria (evidence for sacroiliitis on MRI). The remaining patients had no known evidence of sacroiliitis on MRI (negative or MRI status unknown) and were recruited based on the presence of HLA-B27 plus two other ASAS clinical criteria (on a background of chronic back pain from ≤45 years). As the availability of an MRI was not mandatory for study recruitment there are some patients enrolled via the ASAS clinical criteria for whom MRI status is unknown but who may have also fulfilled the ‘imaging criteria’ for sacroiliitis on MRI when an MRI was made. In addition to fulfilling the classification criteria, all patients had to have an elevated CRP level or active inflammation on MRI as an objective sign for activity. Patients were randomised 1:1:1 to placebo (0.9% saline), or CZP 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 (loading dose) followed by either CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or CZP 400 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W), administered subcutaneously in a prefilled syringe by unblinded trained site personnel. All patients received injections Q2W, either CZP or placebo, to maintain blinding. Randomisation was performed centrally and was stratified by site, mNY criteria and prior TNF inhibitor exposure using an interactive voice/web response system (IXRS). Placebo patients who did not achieve an ASAS20 response at weeks 14 and 16 underwent mandatory escape at week 16 and were randomised to active treatment in a dose-blind manner. CZP patients remained on their original randomised dose regimen (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Study design and patient disposition. A. RAPID-axSpA trial design to week 24 of an ongoing 204-week trial. B. Disposition of patients in the overall axSpA population (RS). axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; CZP, certolizumab pegol; LD, loading dose; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; sc, subcutaneous. *All patients received the allocated treatment. Discontinuations for placebo patients are detailed for time periods prior to and after escape at week 16.

Study procedures and evaluations

Clinical primary endpoint was ASAS20 response at week 12, defined as an improvement of ≥20% and ≥1 unit on a 0–10 NRS in ≥3 of the following: Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PTGADA), Pain assessment (total spinal pain NRS score), Function (represented by Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI)), Inflammation (mean of BASDAI Questions 5 and 6 relating to morning stiffness) and no deterioration (worsening of ≥20% or 1 NRS unit) in the remaining area.29

Key secondary endpoints included ASAS20 at week 24, change from baseline in BASFI,30 31 BASDAI,32 and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) linear33 at weeks 12 and 24. Other secondary endpoints included ASAS40 (≥40% improvement in ASAS domains without any deterioration), ASAS5/6 (≥20% improvement in 5 out of 6 ASAS domains, including spinal mobility and CRP),34 ASAS partial remission (score of ≤2 NRS units in all 4 domains), and BASDAI50 (an improvement of ≥50% in BASDAI compared with baseline). Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) (based on CRP)35 was calculated at each visit as a predefined exploratory endpoint. ASDAS major improvement (a decrease from baseline ASDAS ≥2.0) and ASDAS inactive disease (ASDAS <1.3) were calculated posthoc. For derivation of ASDAS and ASAS 5/6, CRP values below the detection limit were imputed using half this value.36

Statistical analysis

Analyses of primary (ASAS20 at week 12) and key secondary efficacy endpoints (ASAS20 at week 24, change from baseline in BASFI, BASDAI and BASMI linear at weeks 12 and 24) were conducted in the randomised set (RS; all patients randomised to the study with an intention to treat) across the entire axSpA population using a hierarchical test procedure (see online supplementary table S1). All other endpoints were considered exploratory, and include an analysis of key outcomes in the AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations as defined by the local X-ray readings (local assessment). A logistic regression analysis to assess the relative benefit, as defined by ASAS20 response rate at week 12, of CZP in patients with or without evidence of structural damage on X-ray was conducted. A sensitivity analysis was performed for the subset of patients with a centralised X-ray reading (central assessment).

The full analysis set referred to patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication and had a valid baseline and postbaseline measurement for ASAS20 and consisted of all patients in the RS −1 placebo patient. For overall axSpA, a sample size of 105 patients for each treatment group had a 99% power to detect a statistically significant difference in ASAS20 at week 12 between placebo and CZP (assuming 30% difference). Based on recruitment requirements of ≥50% AS patients, this sample size was also considered sufficient to detect a 33% difference in ASAS20 responder rate between placebo and CZP with 90% power.

Differences in ASAS20 responder rates for the two CZP treatment groups versus placebo were assessed using a standard 2-sided Wald asymptotic test with α=0.05. Corresponding 95% CIs for the differences were constructed using asymptotic SEs (asymptotic Wald confidence limits). Changes from baseline in quantitative efficacy measures were analysed with analysis of covariance. Treatment arm and each of the stratification criteria (centres pooled based on geographical region) were included as factors with respective baseline value as a covariate. Results are reported in terms of model-based least-square means.

Missing data due to study withdrawal, any other reason, and all postweek 16 data for placebo patients escaping were imputed using non-responder imputation for ASAS responses and last observation carried forward for BASFI, BASDAI, BASMI linear and ASDAS.

Safety analyses included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication, ≤70 days after the last dose of study medication. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) are reported as the number of patients experiencing each event. The most common AEs classified by MedDRA preferred term are reported.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

The RS consisted of 325 patients randomised to placebo (n=107), CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=111) or CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=107). Overall with local assessment of X-rays, 178 patients (54.8%) met the mNY criteria (defined as the AS subpopulation). Of the 147 nr-axSpA patients, 80 were enrolled via ASAS MRI imaging criteria and the other 67 via ASAS clinical criteria. Mean baseline BASDAI was 6.4 in the overall axSpA population, reflecting high disease activity, and impairments in function and spinal mobility. Treatment groups were generally well balanced (table 1 and see online supplementary table S2). Prior anti-TNFα exposure was higher in the placebo group compared with the CZP groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total axSpA patients, AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations

| Total axSpA | Total axSpA (n=325) | AS (n=178) | nr-axSpA (n=147) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=107) | CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=111) | CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=107) | ||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean yrs (SD) | 39.9 (12.4) | 39.1 (11.9) | 39.8 (11.3) | 39.6 (11.9) | 41.5 (11.6) | 37.4 (11.8) |

| Male, % | 60.7 | 60.4 | 63.6 | 61.5 | 72.5 | 48.3 |

| AxSpA characteristics | ||||||

| Symptom duration, median, yrs (min, max) | 7.7 (0.3, 50.9) | 6.9 (0.3, 34.2) | 7.9 (0.3, 44.8) | 7.7 (0.3, 50.9) | 9.1 (0.3,50.9) | 5.5 (0.3,41.5) |

| Symptom duration <5 years, n (%) | 42 (39.3) | 50 (45.0) | 34 (31.8) | 126 (38.8) | 57 (32.0) | 69 (46.9) |

| Definitive sacroiliitis on X-ray | 57 (53.3) | 65 (58.6) | 56 (52.3) | 178 (54.8) | 178 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Positive for HLA-B27, n (%) | 87 (81.3) | 87 (78.4) | 81 (75.7) | 255 (78.5) | 145 (81.5) | 110 (74.8) |

| CRP mg/L | ||||||

| Median, (min, max) | 15.0 (0.1, 156.2) | 12.7 (0.1, 174.8) | 12.3 (0.1, 159.9) | 13.9 (0.1, 174.8) | 14.3 (0.1,174.8) | 11.9 (0.1,156.2) |

| >ULN, n (%) | 77 (72.0) | 75 (67.6) | 71 (66.4) | 223 (68.6) | 130 (73.0) | 93 (63.3) |

| ≥15 mg/L, n (%) | 53 (49.5) | 42 (37.8) | 38 (35.5) | 133 (40.9) | 80 (44.9) | 53 (36.1) |

| BASDAI,* Mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.7) | 6.5 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.5) | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.5 (1.5) |

| BASFI, * Mean (SD) | 5.5 (2.1) | 5.3 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.3) | 5.7 (2.2) | 4.9 (2.3) |

| BASMI linear,* Mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.8) | 3.7 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.7) | 3.8 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.5) |

| ASDAS,* Mean (SD) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.9) |

| Arthritis,† n (%) | 61 (57.0) | 62 (55.9) | 53 (49.5) | 176 (54.2) | 96 (53.9) | 80 (54.4) |

| Prior and concomitant medication | ||||||

| Concomitant NSAIDs, n (%) | 92 (86.0) | 97 (87.4) | 95 (88.8) | 285 (87.7) | 162 (91.0) | 123 (83.7) |

| Concomitant DMARDs, n (%) | 38 (35.5) | 31 (27.9) | 31 (29.0) | 100 (30.7) | 63 (35.4) | 37 (25.2) |

| Prior anti-TNFα exposure, n (%) | 26 (24.3) | 15 (13.5) | 11 (10.3) | 52 (16.0) | 36 (20.2) | 16 (10.9) |

Unless stated otherwise data refers to the randomised set (RS). AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI linear, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index linear; CRP, C-reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DMARDs, Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen B27; NSAIDs, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α; ULN, upper limit of normal.

*In full analysis set (FAS).

†Current and/or historical; CRP ULN=7.9 mg/L.

Consistent with previous reports, the AS subpopulation had a higher proportion of males, whereas gender balance was approximately equal in the nr-axSpA subpopulation (table 1).37 38 The nr-axSpA subpopulation were, on average, younger, had a shorter time since disease diagnosis, and had lower CRP levels than AS patients (table 1). Except for CRP levels, similar baseline disease activity was observed for AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations. However, nr-axSpA patients reported fewer limitations in physical function and spinal mobility than AS patients, as demonstrated by lower baseline BASFI and BASMI linear scores (table 1).

During the first 24 weeks, a total of 10, 6 and 9 patients discontinued from placebo, CZP 200 mg Q2W, and CZP 400 mg Q4W groups, respectively (figure 1B). Fifty-six placebo patients underwent mandatory escape to active treatment and were rerandomised to CZP treatment groups at week 16 (27 patients to CZP 200 mg Q2W; 29 patients to CZP 400 mg Q4W) (figure 1B). In CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W groups, 35 and 25 patients fulfilled the escape criteria but continued in their original treatment. Concomitant NSAIDs and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD; sulfasalazine and methotrexate) were taken by 87.8% and 30.7% of patients at baseline.

Efficacy

AxSpA population

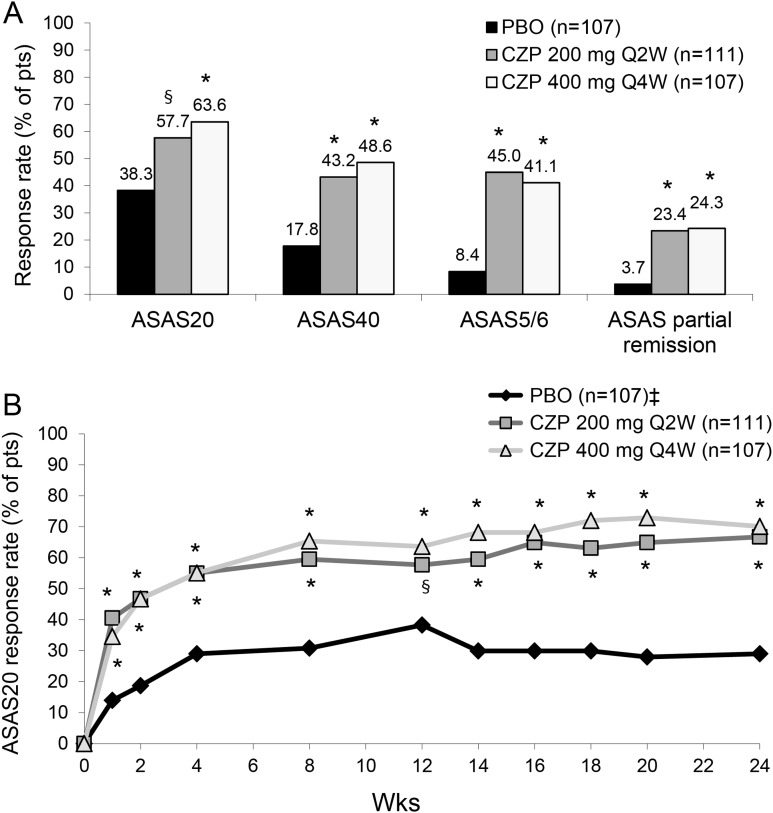

At week 12, a statistically significant higher proportion of patients in the CZP 200 mg Q2W (57.7%) and CZP 400 mg Q4W group (63.6%) achieved an ASAS20 response compared with placebo (38.3%) (p=0.004 and p<0.001, respectively) (figure 2A). This difference in ASAS20 response continued through week 24 in both CZP treatment groups, and was achieved as early as week 1 (p<0.001) (figure 2B). At week 12, more CZP patients also achieved an ASAS40 response, ASAS5/6 response, and ASAS partial remission response versus placebo (p<0.001) (figure 2A). Differences in ASAS responses rates between treatments were maintained, or further improved, at week 24.

Figure 2.

ASAS response rates in axSpA patients at week 12 (A) and up to week 24 (B). A. ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS5/6 and ASAS partial remission response rates at week 12. * p<0.001; § p=0.004 CZP versus PBO (2-sided Wald asymptotic test). B. ASAS20 response rate in the three treatment groups from week 0 to week 24. * p<0.001; § p=0.004 CZP versus PBO (2-sided Wald asymptotic test). ‡ Placebo patients escaping at week 16 (n=56) were considered non-responders at weeks 16–24. Data corresponds to the RS (non-responder imputation). PBO, placebo; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; ASAS20, assessment of Axial SpondyloArthritis international Society 20% response criteria; ASAS40, assessment of Axial SpondyloArthritis international Society 40% response criteria; ASAS5/6: assessment of Axial SpondyloArthritis international Society at least 20% improvement in 5 of 6 domains (including spinal mobility and c-reactive protein).

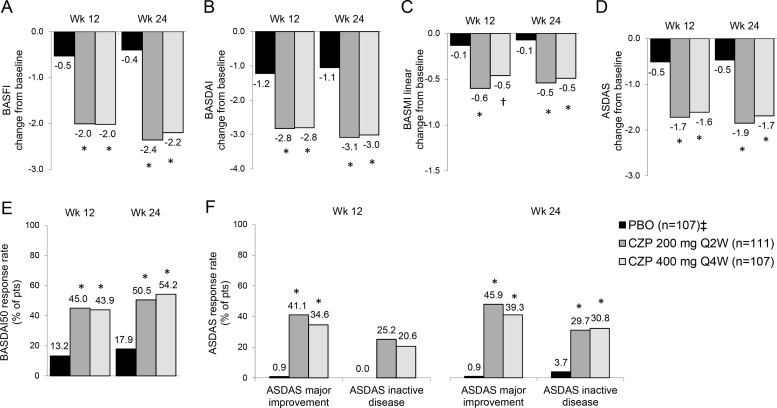

At weeks 12 and 24, CZP treatment resulted in significant improvements in BASFI (figure 3A), BASDAI (figure 3B), BASMI linear (figure 3C) and ASDAS (figure 3D) versus placebo (p<0.001). Improvements in BASFI, BASDAI and BASMI linear were similar between CZP treatment arms and observed from week 1 (see online supplementary figure S1). A higher proportion of CZP-treated axSpA patients achieved BASDAI50 response at weeks 12 and 24 (p<0.001) (figure 3E). At week 12, more CZP patients achieved ASDAS major improvement (41.4% and 34.6% for CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W, respectively) or ASDAS inactive disease (25.2% and 20.6% for CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W, respectively) compared with placebo (ASDAS major improvement 0.9%; ASDAS inactive disease 0.0%) (p<0.001; figure 3F). Higher ASDAS major improvement and inactive disease response rates in CZP-treated patients versus placebo were maintained through week 24 (p<0.001, figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Change from baseline in BASFI, BASDAI, BASMI linear and ASDAS, and response rates for BASDAI50 and ASDAS major improvement or inactive disease at weeks 12 and 24. Change from baseline in A, BASFI; B, BASDAI; C, BASMI linear; and D, ASDAS. E, BASDAI50 response rates expressed as the % of patients achieving ≥50% improvement in BASDAI from baseline. F, ASDAS response rates expressed as the percentage of patients achieving major improvement and inactive disease state. Data are presented for the placebo (PBO), CZP 200 mg Q2W or CZP 400 mg Q4W at week 12 and week 24. * p<0.001; † p<0.05 CZP versus PBO (2-sided Wald asymptotic test). ‡ Placebo patients escaping at week 16 (n=56) were considered non-responders at weeks 16–24. ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index linear; CZP, certolizumab pegol.

AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations

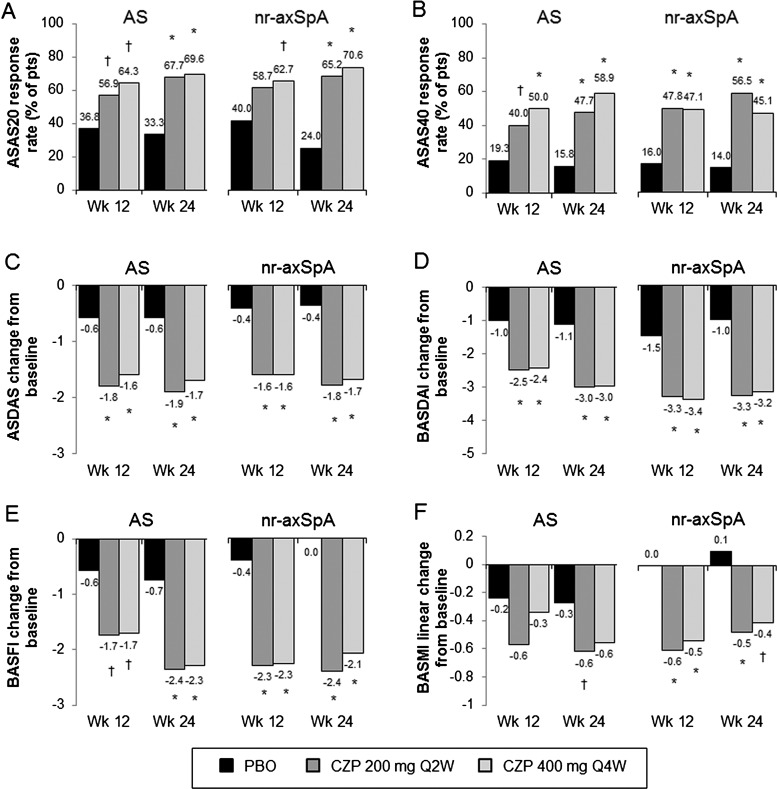

Improvements in the ASAS20 response at week 12 in CZP-treated patients were observed in both AS (56.9% for CZP 200 mg Q2W and 64.3% for CZP 400 mg Q4W vs 36.8% for placebo; p<0.05) and nr-axSpA patients (58.7% for CZP 200 mg Q2W and 62.7% for CZP 400 mg Q4W vs 40.0% for placebo; p=NS and p<0.05, respectively) (figure 4A). Logistic regression analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint did not reveal a difference in treatment effect between AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations (see online supplementary figure S2A). The central reading of the X-rays (central assessment) in a subset of patients (n=282 (87%)) resulted in a reclassification of some patients. However, a sensitivity analysis on this population demonstrated a consistent treatment effect across the AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations, and this reclassification did not have an influence on the overall interpretation of the data (see online supplementary figure S2B).

Figure 4.

Efficacy in AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations at weeks 12 and 24. Responses for the three treatment groups (placebo (PBO), CZP 200 mg Q2W or CZP 400 mg Q4W) at weeks 12 and 24 in: A, ASAS20; B, ASAS40 and C, ASDAS. Change from baseline at weeks 12 and 24 in: D, BASDAI; E, BASFI and F, BASMI linear. All response rates are presented as % of patients. * p<0.001; † p<0.05 CZP versus PBO (2-sided Wald asymptotic test). Escaping PBO patients were considered non-responders week 24. N values for the AS subpopulation are 57, 65 and 56 for the placebo, CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASAS20, assessment of Axial SpondyloArthritis international Society 20% response criteria; ASAS40, assessment of Axial SpondyloArthritis international Society 40% response criteria; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index linear; CZP, certolizumab pegol.

A significant treatment effect was seen for both subpopulations through week 24 (figure 4A). Improvements in ASAS40 response rates (figure 4B), ASDAS change from baseline (figure 4C), and BASDAI change from baseline (figure 4D) were seen in AS and nr-axSpA at weeks 12 and 24. Significant improvements in BASFI and BASMI linear were observed up to week 24 in CZP-treated patients versus placebo in both axSpA subpopulations (figure 4E, F), despite lower baseline BASFI and BASMI linear scores in nr-axSpA patients (see online supplementary figure S3).

Safety

TEAEs were similar between All CZP and placebo groups, mostly mild (56.2% CZP vs 48.6% placebo) to moderate (36.1% CZP vs 33.6% placebo) in severity, and generally considered by the investigator as unrelated to study medication (table 2). The most common infectious AEs were nasopharyngitis (8.8% CZP vs 6.5% placebo) and upper respiratory tract infection (4.0% CZP vs 2.8% placebo) (table 2 and see online supplementary table S3). For non-infectious AEs, headache (6.2% CZP vs 6.5% placebo) and increased blood creatine phosphokinase (5.1% CZP vs 1.9% placebo) were most common. Increases in creatine phosphokinase were transient, resolved spontaneously despite continued CZP therapy, and were often considered by investigators as possibly related to increased physical activity. No elevations were associated with an ischaemic cardiac event or resulted in study discontinuation. Few serious TEAEs were reported overall (4.7% CZP vs 4.7% placebo); no deaths were reported (table 2). Similar pattern of SAEs was observed in AS and the overall axSpA population. Incidence of discontinuation from the RAPID-axSpA study due to TEAEs was low (2.2% CZP vs 1.9% placebo) and consistent with the known safety profile for patients with inflammatory joint diseases receiving TNF inhibitor agents (eg, hypersensitivity and infections). There were no reported cases of opportunistic infections (including tuberculosis) or malignancies. The AEs included 2 and 3 new cases of uveitis in CZP and placebo groups, respectively, and one new case of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in placebo. Detailed information regarding episodes of uveitis was collected; five patients (including four placebo (one who escaped to CZP 200 mg Q2W 4 weeks previously) and one CZP 200 mg Q2W patient) had new onset, or a new episode of, uveitis. For one CZP 200 mg Q2W patient, active uveitis was documented 4 weeks after baseline but not as a new onset.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during the 24-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase, by treatment group in the axSpA population

| Placebo* n=107 n (%) | CZP 200 mg Q2W n=111 n (%) | CZP 400 mg Q4W n=107 n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAEs | 67 (62.6) | 85 (76.6) | 80 (74.8) |

| TEAEs by intensity | |||

| Mild | 52 (48.6) | 65 (58.6) | 64 (59.8) |

| Moderate | 36 (33.6) | 46 (41.4) | 43 (40.2) |

| Severe | 7 (6.5) | 4 (3.6) | 3 (2.8) |

| Drug-related TEAEs | 22 (20.6) | 41 (36.9) | 36 (33.6) |

| Infections† | 25 (23.4) | 43 (38.7) | 41 (38.3) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (6.5) | 11 (9.9) | 11 (10.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 3 (2.8) | 6 (5.4) | 4 (3.7) |

| Serious infections‡ | 0 | 2 (1.8) | 0 |

| Investigations | |||

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 2 (1.9) | 7 (6.3) | 6 (5.6) |

| Injection site reactions§ | 1 (0.9) | 10 (9.0) | 5 (4.7) |

| Injection site pain‡ | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Serious TEAEs by SOC | 5 (4.7) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (6.5) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorder | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions¶ | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.9) |

| Immune system disorders | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Infections and infestations | 0 | 2 (1.8) | 0 |

| Investigations¶ | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Discontinuations due to TEAEs | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (3.7) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*placebo escape at week 16.

†Preferred terms.

‡Serious infections reported: haemophilus infection and laryngitis.

§High-level term.

¶Serious general disorders and administration site conditions was two cases of non-cardiac chest pain; serious investigation TEAE was one case of gamma-glutamyltransferase increased.

CZP, certolizumab pegol.

Discussion

RAPID-axSpA is the first, large, randomised, controlled trial allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the baseline characteristics, burden of disease and treatment efficacy of a TNF inhibitor in axSpA patients, including AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations as defined by ASAS criteria.3 These findings extend those from previous studies in AS that have reported beneficial effects of TNF inhibitors in patients with inadequate response to NSAIDs,14 16–21 as well as patients with early or nr-axSpA.11 23–25 Patients included in the study had to have objective signs of inflammation (eg, positive CRP, active sacroiliitis on MRI) plus an elevated BASDAI and spinal pain score. Inflammation on MRI has been associated with an improved response to TNF-inhibitors39 and satisfies ASAS recommendations for the treatment of axSpA with TNF-inhibitors.22

Baseline disease activity of RAPID-axSpA patient subpopulations supports previous indirect comparisons indicating a similar high burden of disease for AS and nr-axSpA, and emphasises the need to treat both patient subpopulations.11 13 14 Lower BASFI and BASMI linear scores for nr-axSpA patients at baseline indicated lower physical impairment compared to AS patients; possibly due to greater irreversible structural damage in AS.

CZP showed efficacy in reducing the signs and symptoms of axSpA, in AS and nr-axSpA patients. Overall, the primary endpoint was met with significantly more CZP-treated patients (57.7%–63.6%) achieving ASAS20 response at week 12 versus placebo (38.3%). Similar efficacy was shown in AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations, and this was consistent in the subset of patients classified based on the centralised baseline X-ray, highlighting the robustness of this result. The more stringent endpoints of ASAS40, and ASDAS major improvement and inactive disease response rates at weeks 12 and 24, were also met in overall axSpA, AS and nr-axSpA. The onset of CZP action was rapid; improved response rates for ASAS20, ASAS40 and ASDAS were observed as early as week 1 and effects were still apparent at week 24. Improvements were also seen in ASAS5/6 and ASAS partial remission response rates and in change from baseline in BASFI, BASDAI and BASMI linear. Overall, there were no notable differences between the two CZP dosing regimens in the overall axSpA population or either subpopulation, enabling dosing flexibility and the convenience of less frequent dosing in some patients. Elevated creatine phosphokinase levels are in line with previous reports in the spondyloarthropathies40 41 and during TNF inhibitor treatment.42 No new safety signals were observed for CZP in axSpA compared with the reported safety of CZP in RA trials.43 44

Limitations of this report include presentation of 24-week results of the RAPID-axSpA double-blind placebo-controlled trial period; longer-term results will be needed to confirm these initial observations. Although this study includes AS and nr-axSpA patients, it was not designed to examine whether early treatment can prevent structural changes that are characteristic of AS. Furthermore, the outcome measures used in this study have been validated for AS but not for the wider axSpA population or nr-axSpA patients specifically, although nr-axSpA studies indicate that these are valid in this subgroup too.11 23–25 Finally, not all recruited patients had access to MRI; thus, it is not possible to compare nr-axSpA patients recruited on the basis of ASAS clinical versus MRI criteria.

In summary, results of the RAPID-axSpA trial demonstrate that treatment with both CZP-dosing regimens (200 mg Q2W or 400 mg Q4W) is clinically effective with a favourable risk benefit profile up to 24 weeks in patients with active axSpA. Disease activity was similar at baseline between AS and nr-axSpA patients. Rapid improvements in the clinical signs and symptoms were observed in both subpopulations. This novel study, which allows for direct comparison of disease burden and CZP efficacy in AS and nr-axSpA patients in a single study, provides clear support for this treatment option in both patient subpopulations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Owen Davies, UCB Pharma, Brussels, Belgium for critical review of the manuscript; Marine Champsaur, UCB Pharma, Brussels, Belgium for publication coordination; and Costello Medical Consulting, UK, for writing and editorial assistance, which was funded by UCB Pharma.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. Under the heading ‘AS and nr-axSpA subpopulations’ the p values relating to figure 4 have been corrected. In addition, the n values in figure 1A have been corrected.

Funding: The RAPID-axSpA study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Competing interests: RL has received research grants, speaker's fees or consulting fees from Abbott, Ablynx, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB Pharma, Wyeth. JB has received research grants or consulting fees from Abbott, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma. AD has received research grants or consulting fees from Abbott, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, UCB Pharma. MD has received research grants and consulting fees from UCB Pharma. WPM has received research grants, speaker's fees or consulting fees from Abbott, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Synarc, UCB Pharma. PJM received research grants, speaker's fees or consulting fees from Abbott, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Crescendo, Eli-Lilly, Forest, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma. JDR has received consulting fees from Abbott, UCB Pharma. MR has received consulting fees from Abbott, Bristol Myers Squibb, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma. DvdH has received research grants or consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, Chugai, Daiichi, Eli-Lilly, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB Pharma, Vertex and is the director of Imaging Rheumatology bv. CS, BH, AF, GC and MdL are shareholders and/or employees of UCB Pharma. JS has received speaker's fees or consulting fees from Abbott, Eli-Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board at participating sites.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:770–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Berg R, de Hooge M, Rudwaleit M, et al. ASAS modification of the Berlin algorithm for diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis: results from the SPondyloArthritis Caught Early (SPACE)-cohort and from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)-cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1646–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan MA, et al. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:535–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1000–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M. Early spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2012;38:387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. Referral strategies for early diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:262–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sieper J, van der Heijde D. Review: Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: new definition of an old disease? Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:543–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Listing J, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab in the treatment of axial spondylarthritis without radiographically defined sacroiliitis: results of a twelve-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial followed by an open-label extension up to week fifty-two. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:1981–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landewé R, Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of ankylosing spondyltitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 24 week results of a double blind randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 axial spondyloarthritis study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:S336–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:717–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2136–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:442–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, et al. Persistent clinical response to the anti-TNF-alpha antibody infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 3 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:670–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Two year maintenance of efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:229–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2002;359:1187–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis JC, Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3230–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis JC, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, et al. Sustained durability and tolerability of etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis for 96 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1557–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:582–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Maksymowych WP, et al. 2010 Update of the international ASAS recommendations for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:905–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barkham N, Keen HI, Coates LC, et al. Clinical and imaging efficacy of infliximab in HLA-B27-Positive patients with magnetic resonance imaging-determined early sacroiliitis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:946–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:815–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song IH, Hermann K, Haibel H, et al. Effects of etanercept versus sulfasalazine in early axial spondyloarthritis on active inflammatory lesions as detected by whole-b): a 48-week randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:590–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song IH, Weiß A, Hermann KG, et al. Similar response rates in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis after 1 year of treatment with etanercept: results from the ESTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:823–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a Phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:48–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Heijde D, Fleischmann R, Wollenhaupt J, et al. Effect of different imputation approaches on the evaluation of radiographic progression in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of the RAPID-PsA 24-week phase III double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study of certolizumab pegol. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:233–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1876–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Davis J, et al. ASsessment in ankylosing spondylitis international working group/spondylitis association of America recommendations for conducting clinical trials in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:386–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Feldtkeller E. Proposal of a linear definition of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and comparison with the 2-step and 10-step definitions. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:489–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandt J, Listing J, Sieper J, et al. Development and preselection of criteria for short term improvement after anti-TNF alpha treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1438–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1811–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calin A, Fries JF. Striking prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in “healthy” w27 positive males and females. N Engl J Med 1975;293:835–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gran JT, Husby G, Hordvik M. Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in males and females in a young middle-aged population of Tromso, northern Norway. Ann Rheum Dis 1985;44:359–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudwaleit M, Schwarzlose S, Hilgert ES, et al. MRI in predicting a major clinical response to anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1276–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calin A. Raised serum creatine phosphokinase activity in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 1975;34:244–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bohan A, Stracner J, Norton S. CPK elevation in the spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol 1990;17:565–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. AnnRheum Dis 2013;72:1605–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keystone E, van der Heijde D, Mason D, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smolen J, Landewé R, Mease P, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:797–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.