Abstract

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and obesity have become increasingly prevalent in recent years. Recent studies have focused on identifying causal variations or candidate genes for obesity and T2DM via analysis of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) within a single tissue. T2DM and obesity are affected by comprehensive sets of genes in multiple tissues. In the current study, gene expression levels in multiple human tissues from GEO datasets were analyzed, and 21 candidate genes displaying high percentages of differential expression were filtered out. Specifically, DENND1B, LYN, MRPL30, POC1B, PRKCB, RP4-655J12.3, HIBADH, and TMBIM4 were identified from the T2DM-control study, and BCAT1, BMP2K, CSRNP2, MYNN, NCKAP5L, SAP30BP, SLC35B4, SP1, BAP1, GRB14, HSP90AB1, ITGA5, and TOMM5 were identified from the obesity-control study. The majority of these genes are known to be involved in T2DM and obesity. Therefore, analysis of gene expression in various tissues using GEO datasets may be an effective and feasible method to determine novel or causal genes associated with T2DM and obesity.

1. Introduction

T2DM, a complex endocrine and metabolic disorder, has become more prevalent in recent years, with significant adverse effects on human health. T2DM is characterized by insulin resistance (IR) and deficient β-cell function [1]. Interactions between multiple genetic and environmental factors are proposed to contribute to pathogenesis of the disease [1, 2]. Association of obesity with T2DM has been reported, both within and among different populations [3]. Earlier research has shown that obesity and its duration are major risk factors for T2DM, and IR pathological state generally exists in obesity [4, 5].

In recent years, numerous susceptibility loci have been identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and meta-analyses on T2DM and obesity, and nearby candidate genes are proposed to be directly involved in the diseases [6, 7]. However, the underlying mechanisms by which these susceptibility loci affect and cause T2DM or obesity are currently unclear. Known SNPs associated with disease typically account for only a small fraction of overall disease [8, 9]. Gene expression patterns play a key role in determining pathogenesis and candidate genes of T2DM and obesity. A large-scale computable model has been created to analyze the molecular actions and effects of insulin on muscle gene expression [10]. Based on GWAS results, investigators integrated expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) with coexpression networks to establish novel genes and networks relevant to the disease. Sixty-two candidate genes were identified through integrating 32 SNPs associated with T2DM and nearby gene expression from blood samples of 1008 morbidly obese patients. Many of the highly ranked genes are known to be involved in the regulation and metabolism of insulin, glucose, and lipids [11].

Different gene expression patterns exist in various tissues of organisms, and complex metabolic diseases, such as T2DM and obesity, are affected by comprehensive gene expression in multiple tissues. Analysis of gene expression in six tissues of mice from obesity-induced diabetes-resistant and diabetes-susceptible strains before and after the onset of diabetes led to the identification of 105 coexpression gene modules [12]. In the present study, gene expression profiles of human skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, islet, liver, blood and arterial tissue (or skeletal muscle, omental adipose tissue, cumulus cells, liver, blood, and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue) from GEO datasets were analyzed to identify the candidate genes for T2DM and obesity. Furthermore, candidate genes 1 Mb upstream and downstream (±1 Mb) of susceptibility SNPs for human T2DM and obesity were screened. Our analysis of gene expression in various tissues using GEO datasets provides a valuable method to determine novel candidate genes for T2DM and obesity.

2. Materials and Methods

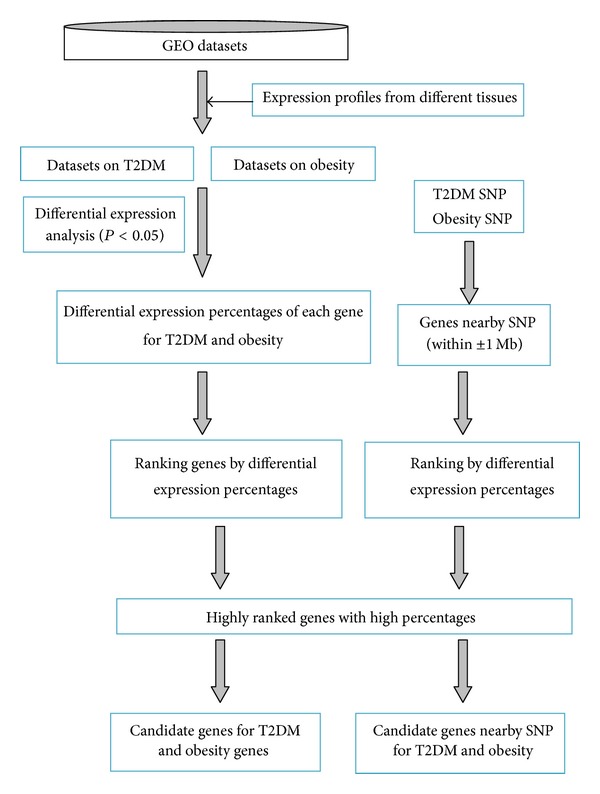

The overall experimental design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall experimental design.

2.1. GEO Dataset Selection and Statistical Analysis

Human GEO datasets for T2DM or obesity were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database of NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). In total, 23 datasets (14 for T2DM and 9 for obesity) were selected and downloaded. Some datasets were separated into several groups according to sample phenotype. Overall, 21 groups for T2DM and 14 for obesity were obtained. Samples of disease and control were included in the case and control subgroups, respectively (details of samples for each group are provided in Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/970435). Three or more samples were included in each case or control subgroup for every microarray experiment. CEL files of samples were submitted to RMAExpress, Version 1.0.4, to yield normalized log2 expression values for each probe in individual groups with default parameters [13]. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normalized log2 expression values of two independent samples in each group was performed with the F test. The t-test for equal or unequal variances was used, depending on the P-value of the F tests.

Gene annotation files were downloaded from Ensembl (http://asia.ensembl.org/biomart/martview/45e0798c53bbd97ed0cf3d61142da3df) depending on the platform (GPL) of each group. Probes were matched with unique genes through gene annotation files. Probes corresponding to more than one gene were excluded. Probes or genes with significant differential expression were defined as P-value ≤ 0.05. We calculated the differential expression (P ≤ 0.05) percentage of each gene in all 21 T2DM and 14 obesity groups. For a gene with several probes, P values ≤ 0.05 were selected to represent significance.

2.2. Statistical Analysis of Differential Expression Percentages of Genes

Genes were ranked based on differential expression in the T2DM and obesity groups. Genes with the highest percentage of differential expression were identified as candidates (≥50% for T2DM and ≥60% for obesity). Ranked genes are presented in Supplementary Materials (Table S2).

2.3. Screening of Genes within ±1 Mb of Susceptibility SNPs for T2DM and Obesity

In total, 54 and 95 SNPs associated with T2DM and obesity, respectively, were selected (P ≤ 5 × 10−8, detailed information in Tables S3 and S4). The coordinate of each SNP in the chromosome was searched in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/). Consensus CDS (CCDS) files for human data were downloaded (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/CCDS/), and genes within ±1 Mb of SNPs were filtered out. Overall, 445 and 917 genes within 2 Mb of SNPs were associated with T2DM and obesity, respectively. The genes were reordered based on differential expression percentages with the above method, and those with the highest percentages were selected as candidates for T2DM (>40%) and obesity (>50%). Detailed information on all ranked genes in close proximity to SNPs is provided in Supplementary Materials (Table S5).

2.4. GO (Gene Ontology) and Pathway Analysis of Candidate Genes

Enrichment analysis of GO and pathways of all candidate genes was performed using Capital Bio Molecule Annotation System 3 (http://bioinfo.capitalbio.com/mas3/).

3. Results

3.1. Candidate Genes for T2DM and Obesity

In total, expression patterns of 23,810 genes were analyzed in the T2DM-control study. All genes were ranked based on the differential expression percentage. The average percentage of all genes was ~11%. Six highly ranked genes (DENND1B, LYN, MRPL30, POC1B, PRKCB, and RP4-655J12.3) were identified as candidates for T2DM (Table 1).

Table 1.

Highly ranked genes in T2DM-control study.

(a) Highly ranked genes with high percentages in T2DM-control study

| Gene symbol | Official full name | Location | Percentage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYN | v-yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral related oncogene homolog | Chr8 56,792,386-56,925,006 (+): 8q13 |

61.1% | Mller et al., 2000 [14] |

|

| ||||

| DENND1B | DENN domain-containing protein 1B | Chr1 197,473,878-197,744,623 (−): 1q31.3 |

50% | |

|

| ||||

| MRPL30 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L30 | Chr2 99,797,542-99,816,020 (+): 2q11.2 |

50% | |

|

| ||||

| POC1B | POC1 centriolar protein homolog B (Chlamydomonas) | Chr12 89,813,495-89,920,039 (−): 12q21.33 |

50% | |

|

| ||||

| PRKCB | Protein kinase C betatype PKC-beta (PKC-B) | Chr16 23,847,300-24,231,932 (+): 16p11.2 |

50% | Zhang et al., 2004 [22] |

|

| ||||

| RP4-655J12.3 | Chr1 116,916,755-116,917,283 (−): N/A |

50% | ||

(b) Highly ranked genes nearby SNPs conferring susceptibility to T2DM

| Gene symbol | Official full name | Location | Percentage | References | SNPs (Chr pos; frequencies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIBADH | 3-Hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase | Chr7 27,565,059-27,702,620 (−): 7p15.2 |

42.9% | Deng et al., 2010 [15] | rs864745 (28,180,556; T = 0.65, C = 0.35); rs849134 (28,196,222; A = 0.65, G = 0.35) |

|

| |||||

| TMBIM4 | Transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif containing 4 | Chr12 66,530,717-66,563,807 (−): 12q14.1-q15 |

42.9% | rs1531343 (66,174,894; G = 0.81, C = 0.19) |

|

Note: Chr pos: chromosome position; frequencies: the allele frequencies in 1000 genomes (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/tools/1000genomes/).

Since less groups were available for the obesity-control study, genes with fewer than 10 P values were excluded in order to obtain better statistical results. Expression of 14,367 genes was analyzed using the above method. The average percentage of all genes was ~17.5%. Eight genes (BCAT1, BMP2 K, CSRNP2, MYNN, NCKAP5L, SAP30BP, SLC35B4, and SP1) were isolated as candidates for obesity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Highly ranked genes in the obesity-control study.

(a) Highly ranked genes with high percentages in obesity-control study

| Gene symbol | Official full name | Location | Percentage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCAT1 | Branched chain amino-acid transaminase1 | Chr12 24,962,958-25,102,393 (−): 12p12.1 |

63.6% | |

|

| ||||

| BMP2K | BMP2 inducible kinase | Chr4 79,697,532-79,833,341 (+): 4q21.21 |

63.6% | |

|

| ||||

| CSRNP2 | Cysteine-serine-rich nuclear protein 2 | Chr12 51,454,988-51,477,454 (−): 12q13.11-q13.12 |

63.6% | |

|

| ||||

| MYNN | Myoneurin | Chr3 169,490,853-169,507,504 (+): 3q26.2 |

63.6% | Stewart et al., 2010 [38] |

|

| ||||

| NCKAP5L | NCK-associated protein 5-like | Chr12 50,184,929-50,222,208 (−): 12q13.12 |

63.6% | |

|

| ||||

| SAP30BP | SAP30 binding protein | Chr17 73,663,399-73,704,139 (+): 17q25.1 |

63.6% | Naukkarinen et al., 2010 [39] |

|

| ||||

| SLC35B4 | Solute carrier family 35, member B4 | Chr7 133,974,089-134,001,827 (−): 7q33 |

63.6% | Fox et al., 2007 [16]; Yazbek et al., 2011 [17] |

|

| ||||

| SP1 | Sp1 transcription factor | Chr12 53,773,979-53,810,230 (+): 12q13.1 |

63.6% | |

(b) Highly ranked genes nearby SNPs conferring susceptibility to obesity

| Gene symbol | Official full name | Location | Percentage | References | SNPs (Chr pos; frequencies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCKAP5L | NCK-associated protein 5-like | Chr12 50,184,929-50,222,208 (−): 12q13.12 |

63.6% | rs7132908 (50,263,148; G = 0.73; A = 0.27) |

|

|

| |||||

| SP1 | Sp1 transcription factor | Chr12 53,773,979-53,810,230 (+): 12q13.12 |

63.6% | rs1443512 (54,342,684; A = 0.31; C = 0.69) |

|

|

| |||||

| ITGA5 | Integrin, alpha 5 | Chr12 54,789,045-54,813,050 (−): 12q11-q13 |

58.3% | rs1443512 (54,342,684; A = 0.31; C = 0.69) |

|

|

| |||||

| TOMM5 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 5 | Chr9 37,588,410-37,592,636 (−): 9p13.2 |

57.1% | rs16933812 (36,969,205; G = 0.40, T = 0.60) |

|

|

| |||||

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein 90 kDa alpha (cytosolic), class B member 1 | Chr6 44,214,849-44,221,614 (+): 6p12 |

55.6% | rs6905288 (43,758,873; G = 0.38, A = 0.62) |

|

|

| |||||

| BAP1 | BRCA1 associated protein-1 | Chr3 52,435,024-52,444,009 (−): 3p21.31-p21.2 |

50% | rs6784615 (52,506,426; C = 0.04, T = 0.96) |

|

|

| |||||

| GRB14 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 | Chr2 165,349,323-165,478,360 (−): 2q22-q24 |

50% | Cooney et al., 2004 [18]; Holt et al., 2009. [19] | rs10195252 (165,513,091; T = 0.60, C = 0.40) |

Note: Chr pos: chromosome position; frequencies: the allele frequencies in 1000 genomes (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/tools/1000genomes/).

3.2. Candidate Genes within ±1 Mb of SNPs Conferring Susceptibility to T2DM and Obesity

In total, 445 genes in close proximity to T2DM SNPs were reordered based on their differential expression percentages. In particular, two highly ranked genes, HIBADH and TMBIM4, within ±1 Mb of rs864745, rs849134, and rs1531343 SNPs were filtered out (Table 1).

Using the same method, seven highly ranked genes (BAP1, GRB14, HSP90AB1, ITGA5, NCKAP5L, SP1, and TOMM5) within ±1 Mb of obesity SNPs were identified (Table 2).

Gene symbols and the corresponding full names of all candidate genes are supplied in Tables 1 and 2.

3.3. GO and Pathway Analysis of Candidate Genes

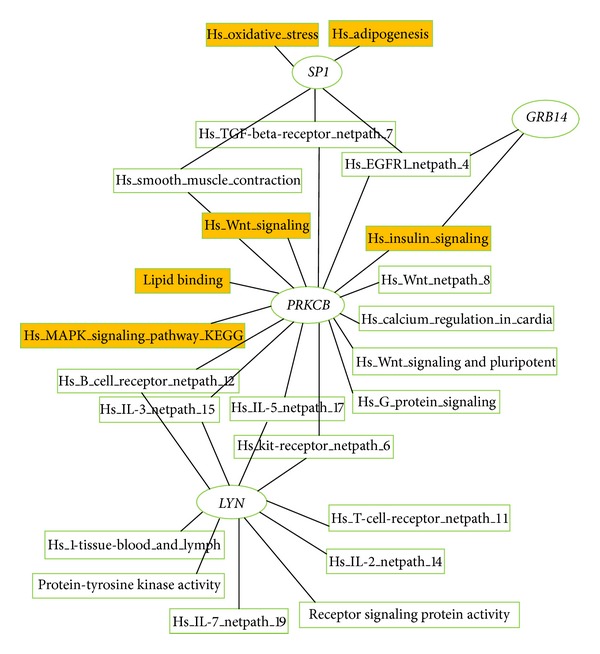

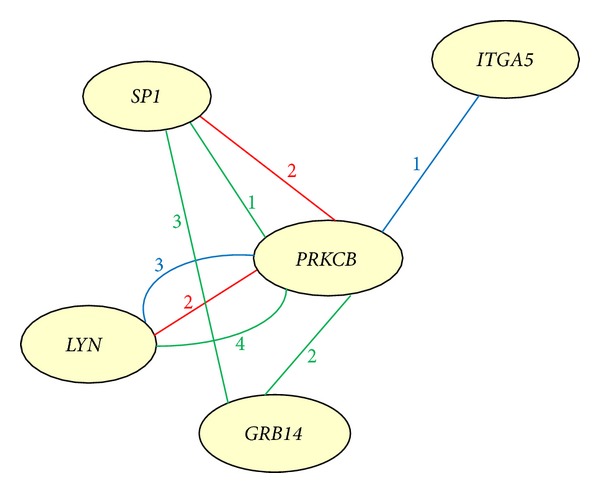

Results of GO and pathway analyses revealed that PRKCB is mainly associated with T2DM, and PRKCB and GRB14 are involved in insulin signaling within the gene pathway network (Figure 2). Further analysis of the correlation pathways of genes disclosed that PRKCB, SP1, GRB14, LYN, and ITGA5 are correlated with each other (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Enrichment analysis of GO and pathways for all genes. Yellow represents pathway directly or indirectly related to T2DM or obesity.

Figure 3.

Correlation pathways of candidate genes. Red line, BioCarta; green line, GenMAPP; blue line, KEGG; number: counts of correlation pathways of two genes.

4. Discussion

Complex metabolic diseases are often caused by alterations in gene expression or metabolic pathways in various tissues. Here, we analyzed differences in gene expression levels in various human tissues from GEO datasets in T2DM- or obesity-control experiments with the t-test. The P values were adjusted using the Bonferroni or FDR method [20] to allow for multiple testing. We introduced strict criteria with FDR ≤ 0.05. However, with these criteria, no genes were filtered out in most groups (16 of 21 groups, Table S6), while the percentage of genes with t-test P values ≤ 0.05 was lower than 10% in most groups (15 of 21 groups, Table S6). Therefore, the t-test statistic was ultimately applied for the present study. In total, we filtered out 21 candidate genes (8 for T2DM and 13 for obesity). The list of up- and downregulated candidate genes is provided in Supplementary Material (Table S7). Similarly, an eGWAS was performed across 130 independent experiments in human, rat, and mouse to identify additional genes implicated in the molecular pathogenesis of T2DM [21]. Interestingly, the same genes were not identified among the different studies. These discrepancies may be attributed to the use of various species, statistical methods, and tissues by different groups.

Analysis of the correlation pathways of the identified genes revealed that PRKCB, SP1, GRB14, LYN, and ITGA5 are correlated with each other (Figures 2 and 3). The proteins interact directly within cells or indirectly among different tissues in the etiological process of T2DM or obesity. PRKCB mediates Ca2+ and DAG-evoked insulin secretion processes in Langerhans' β cells [22], functions downstream of insulin-receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) in muscle cells, and participates in the regulation of glucose transport in adipocytes by negatively modulating insulin-stimulated translocation of the glucose transporter, SLC2A4/GLUT4 [23, 24]. Under high glucose conditions in pancreatic beta cells, PRKCB may be involved in the inhibition of insulin gene transcription [25]. In the present study, we observed PRKCB upregulation in skeletal muscle, islets, adipose tissue, and blood and downregulation in liver of T2DM individuals (Table S7). These findings suggest that PRKCB may be involved in IR and deficient β-cell function in vivo. GRB14 binds directly to IR and regulates insulin-induced IR tyrosine phosphorylation [19]. GRB14-deficient mice display enhanced insulin signaling via IRS1 and AKT activation in liver and skeletal muscle, despite lower circulating insulin levels [18]. An earlier study showed increased GRB14 expression in adipose tissues of both ob/ob mice and Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats, but no changes in liver [26]. In our experiments, GRB14 expression was similarly increased in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese humans, while a decrease was observed in liver (Table S7). In addition, GRB14 is located within ±1 Mb of obese SNP rs10195252, and the rs10195252 T-allele is associated with increased GRB14 subcutaneous adipose tissue mRNA expression [27]. However, LYN is implicated in the insulin signaling pathway via phosphorylation of IRS1 and PI3 K in liver and adipose tissues [14]. The insulin secretagogue, glimepiride, activates LYN in adipocytes [28]. This indirect LYN activation may modulate glycemic control activity of glimepiride in the extrapancreatic environment [28, 29]. In the present study, LYN expression was increased in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and blood of T2DM individuals, while a decrease was observed in islets and liver (Table S7). Moreover, LYN is a highly ranked gene with the highest differential expression percentage in the T2DM-control study (61.1%) and may therefore be a valuable candidate gene for future T2DM research. ITGA5 additionally promotes PI3 K and AKT phosphorylation [30]. ITGA5 expression was shown to be upregulated in adipose tissue of New Zealand obese (NZO) mice (high fat diet versus standard diet) [31]. We observed increased expression of ITGA5 in human subcutaneous adipose tissue (Table S7). Moreover, ITGA5 is located within ±1 Mb of the obesity SNP, rs1443512. SP1 is a zinc finger transcription factor that binds to GC-rich motifs and may be involved in insulin-mediated glucose uptake through positively regulating Glut4 expression in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and heart [32, 33]. SP1 was downregulated in adipose tissue, while increased expression was observed in blood. Pathway analysis revealed the involvement of SP1 in oxidative stress and adipogenesis (Figure 2). SP1 not only is located within ±1 Mb of obesity SNP rs1443512 (similar to ITGA5), but also has the highest differential expression percentage (63.6%). Therefore, further studies are necessary to determine whether rs1443512 is related to ITGA5 or SP1 expression.

Differential expression of HIBADH ((+) 5.1e − 03) was reported in liver mitochondria during development of Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats [15]. We observed no changes in HIBADH expression in liver, while a decrease was evident in skeletal muscle and blood of humans with T2DM. In addition, HIBADH is located within ±1 Mb of T2DM SNPs, rs864745, and rs849134. The association of HIBADH with T2DM requires further evaluation.An earlier study reported higher BCAT1 expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue of females in the insulin-resistant than insulin-sensitive group [34]. Interestingly, higher BCAT1 expression was observed in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese humans in this study. We additionally recorded an increase in blood and decrease in omental adipose tissue (Table S7). BCAT1 has been identified as the optimal marker for weight regain [35]. Moreover, the rs2242400 polymorphism in BCAT1 appears to be associated with T2DM in more than one population [36]. SLC35B4 has been identified as a potential regulator of obesity and insulin resistance in mouse models. Both in vivo and in vitro studies in mice disclosed that decreased SLC35B4 expression is associated with a decrease in gluconeogenesis [17]. An increase in SLC35B4 expression was observed in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese humans in our study (Table S7). Interestingly, a SNP in the human SLC35B4 gene (rs1619682) is associated with waist circumference [16]. HSP90AB1 mRNA is reported to be upregulated in 3T3-L1 cells 6 h after stimulation of adipogenesis [37]. Moreover, HSP90AB1 is located near the obesity SNP, rs6905288. Expression levels of MYNN are negatively correlated to BW (body weight) in adipose tissues of F2 mice (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) [38]. Consistently, our data showed that MYNN expression is downregulated in subcutaneous adipose of obese humans (Table S7). Furthermore, SAP30BP may be involved in body mass index (BMI) in adipose tissue (Pearson correlation (−0.51)) [39]. A decrease in SAP30BP expression was detected in subcutaneous adipocytes of obese human subjects in the present study (Table S7).

The rest of the candidates, C2orf15, DENND1B, MRPL30, POC1B, RP4-655J12.3, TMBIM4, BMP2 K, CSRNP2, NCKAP5L, TOMM5, and BAP1, may be novel genes related to T2DM or obesity. TMBIM4 is located within ±1 Mb of the SNP rs1531343 conferring susceptibility to T2DM, while NCKAP5L, TOMM5, and BAP1 are mapped within ±1 Mb of SNPs conferring susceptibility to obesity. TMBIM4 encodes transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif containing 4, which inhibits apoptosis induced by intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli and modulates both capacitative Ca2+ entry and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated Ca2+ release [40]. In our study, TMBIM4 was mainly upregulated in skeletal muscle, while downregulation was observed in liver (Table S7). The NCKAP5L gene encoding Nck-associated protein 5-like displayed upregulation in adipose tissue but was downregulated in blood (Table S7). TOMM5 encodes the mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM5 homolog. TOMM5 was mainly involved in four GO terms (GO:0008565, protein transporter activity; GO:0015031, protein transport; GO:0005739, mitochondrion; GO:0005742, mitochondrial outer membrane). BAP1 (ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase) localizes at the nucleus and contains three domains (a ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (UCH) with an N-terminal catalytic domain, a unique linker region, and a C-terminal domain). The UCH domain conveys deubiquitinase activity to BAP1 [41]. In flies and humans, the Polycomb repressive deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex is formed through interactions of BAP1 and ASXL1 [42]. DENND1B may promote the exchange of GDP with GTP and play a role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis [43]. The product of MRPL30 is a constituent of mitochondrial ribosomes. POC1B is involved in the early steps of centriole duplication and the later steps of centriole length control [44, 45]. The CSRNP2 protein binds to the consensus sequence, 5′-AGAGTG-3′, and has a transcriptional activator. However, C2orf15 and RP4-655J12.3 have been rarely reported in databases or publications to date. Associations of all new candidate genes identified in the present study with obesity or T2DM require verification in future analyses.

5. Conclusions

LYN, a gene reported to be involved in the insulin pathway, was highly ranked with the highest differential expression percentage in the T2DM-control study (61.1%) and may therefore be a valuable candidate gene for future T2DM research. NCKAP5L with the highest differential expression percentage (63.6%) was located within ±1 Mb of the obesity susceptibility SNP, rs7132908, and was thus identified as the most likely novel candidate gene for obesity. We conclude that analysis of gene expression in various tissues via GEO datasets is an effective and feasible method to identify novel or causal genes associated with T2DM and obesity.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 Samples of each dataset studied in present study. Note; some datasets might be divided into two or more groups depending on sample phenotype.

Supplementary Table S2 All genes ranked by differential expression percentage.

Supplementary Table S3 Details about SNPs susceptibility to T2DM.

Supplementary Table S4 Details about SNPs susceptibility to obesity.

Supplementary Table S5 Ranked genes located within ± 1Mb of SNPs susceptibility to T2DM or obesity.

Supplementary Table S6 Comparison of p-values before and after adjusting by FDR.

Supplementary Table S7 Up- and down- expression of candidate genes in T2DM- and obesity-control study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Science and Technology Major Project of Key Drug Innovation and Development (2011ZX09307-303-03), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31340045), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (2012B060300006), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2012zz0091), and the BGI-SCUT Innovation Fund Project (SW20130802).

References

- 1.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, Van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. The Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dedoussis GVZ, Kaliora AC, Panagiotakos DB. Genes, diet and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Review of Diabetic Studies. 2007;4(1):13–24. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2007.4.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West KM, Kalbfleisch JM. Influence of nutritional factors on prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes. 1971;20(2):99–108. doi: 10.2337/diab.20.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Mitchell BD, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Incidence of type II diabetes in Mexican Americans predicted by fasting insulin and glucose levels, obesity, and body-fat distribution. Diabetes. 1990;39(3):283–288. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lillioja S, Mott DM, Spraul M, et al. Insulin resistance and insulin secretory dysfunction as precursors of non- insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: prospective studies of Pima Indians. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(27):1988–1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fall T, Ingelsson E. Genome-wide association studies of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey JP. Genomewide association studies and assessment of risk of disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(21):2076–2077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1010310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollard J, Jr., Butte AJ, Hoberman S, Joshi M, Levy J, Pappo J. A computational model to define the molecular causes of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2005;7(2):323–336. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang HP, Yang X, Chen R, et al. Integration of disease-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms, expression quantitative trait loci and coexpression networks reveal novel candidate genes for type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2205–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2568-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller MP, Choi Y, Wang P, et al. A gene expression network model of type 2 diabetes links cell cycle regulation in islets with diabetes susceptibility. Genome Research. 2008;18(5):706–716. doi: 10.1101/gr.074914.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Åstrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller G, Wied S, Frick W. Cross talk of pp125(FAK) and pp59(Lyn) non-receptor tyrosine kinases to insulin-mimetic signaling in adipocytes. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(13):4708–4723. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4708-4723.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng W-J, Nie S, Dai J, Wu J-R, Zeng R. Proteome, phosphoproteome, and hydroxyproteome of liver mitochondria in diabetic rats at early pathogenic stages. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2010;9(1):100–116. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900020-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox CS, Heard-Costa N, Cupples LA, Dupuis J, Vasan RS, Atwood LD. Genome-wide association to body mass index and waist circumference: the Framingham Heart Study 100K project. BMC Medical Genetics. 2007;8(supplement 1, article S18) doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazbek SN, Buchner DA, Geisinger JM, et al. Deep congenic analysis identifies many strong, context-dependent QTLs, one of which, Slc35b4, regulates obesity and glucose homeostasis. Genome Research. 2011;21(7):1065–1073. doi: 10.1101/gr.120741.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooney GJ, Lyons RJ, Crew AJ, et al. Improved glucose homeostasis and enhanced insulin signalling in Grb14-deficient mice. The EMBO Journal. 2004;23(3):582–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt LJ, Lyons RJ, Ryan AS, et al. Dual ablation of Grb10 and Grb14 in mice reveals their combined role in regulation of insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. Molecular Endocrinology. 2009;23(9):1406–1414. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawitan Y, Michiels S, Koscielny S, Gusnanto A, Ploner A. False discovery rate, sensitivity and sample size for microarray studies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(13):3017–3024. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama K, Horikoshi M, Toda K, et al. Expression-based genome-wide association study links the receptor CD44 in adipose tissue with type 2 diabetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:7049–7054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114513109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Nagasawa M, Yamada S, Mogami H, Suzuki Y, Kojima I. Bimodal role of conventional protein kinase C in insulin secretion from rat pancreatic β cells. Journal of Physiology. 2004;561(1):133–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Standaert ML, Galloway L, Karnam P, Bandyopadhyay G, Moscat J, Farese RV. Protein kinase C-ζ as a downstream effector of phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase during insulin stimulation in rat adipocytes. Potential role in glucose transport. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(48):30075–30082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright DC, Fick CA, Olesen JB, Craig BW. Evidence for the involvement of a phospholipase C—protein kinase C signaling pathway in insulin stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Life Sciences. 2003;73(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7(2):85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cariou B, Capitaine N, Le Marcis V, et al. Increased adipose tissue expression of Grb14 in several models of insulin resistance. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18(9):965–967. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0824fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schleinitz D, Kloting N, Lindgren CM, et al. Fat depot-specific mRNA expression of novel loci associated with waist-hip ratio. International Journal of Obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller G. The molecular mechanism of the insulin-mimetic/sensitizing activity of the antidiabetic sulfonylurea drug Amaryl. Molecular Medicine. 2000;6(11):907–933. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller G, Schulz A, Wied S, Frick W. Regulation of lipid raft proteins by glimepiride- and insulin-induced glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in rat adipocytes. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;69(5):761–780. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urtasun R, Lopategi A, George J, et al. Osteopontin, an oxidant stress sensitive cytokine, up-regulates collagen-I via integrin αVβ3 engagement and PI3K/pAkt/NFκB signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55(2):594–608. doi: 10.1002/hep.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balwierz A, Polus A, Razny U, et al. Angiogenesis in the New Zealand obese mouse model fed with high fat diet. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2009;8, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn BB. Glucose transport: pivotal step in insulin action. Diabetes. 1996;45(11):1644–1654. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.11.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rüegg J, Cai W, Karimi M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of glucose transporter 4 by estrogen receptor β . Molecular Endocrinology. 2011;25(12):2017–2028. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soronen J, Laurila P-PP-P, Naukkarinen J, et al. Adipose tissue gene expression analysis reveals changes in inflammatory, mitochondrial respiratory and lipid metabolic pathways in obese insulin-resistant subjects. BMC Medical Genomics. 2012;5, article 9 doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viguerie N, Montastier E, Maoret JJ, et al. Determinants of human adipose tissue gene expression: impact of diet, sex, metabolic status, and cis genetic regulation. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002959.e1002959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rampersaud E, Damcott CM, Fu M, et al. Identification of novel candidate genes for type 2 diabetes from a genome-wide association scan in the old order amish: evidence for replication from diabetes-related quantitative traits and from independent populations. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):3053–3062. doi: 10.2337/db07-0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fromm-Dornieden C, von der Heyde S, Lytovchenko O, et al. Novel polysome messages and changes in translational activity appear after induction of adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. BMC Molecular Biology. 2012:p. 13, article 9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart TP, Kim HY, Saxton AM, Kim JH. Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 713) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naukkarinen J, Surakka I, Pietiläinen KH, et al. Use of genome-wide expression data to mine the “Gray Zone” of GWA studies leads to novel candidate obesity genes. PLoS Genetics. 2010;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000976.e1000976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gubser C, Bergamaschi D, Hollinshead M, Lu X, van Kuppeveld FJM, Smith GL. A new inhibitor of apoptosis from vaccinia virus and eukaryotes. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3(2):p. e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen DE, Proctor M, Marquis ST, et al. BAP1: a novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene. 1998;16(9):1097–1112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbaszadegan H, Von Sivers K, Jonsson U. Late displacement of Colles’ fractures. International Orthopaedics. 1988;12(3):197–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00547163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimura S-I, Gerondopoulos A, Linford A, Rigden DJ, Barr FA. Family-wide characterization of the DENN domain Rab GDP-GTP exchange factors. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;191(2):367–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller LC, Geimer S, Romijn E, Yates J, Zamora I, Marshall WF. Molecular architecture of the centriole proteome: the conserved WD40 domain protein POC1 is required for centriole duplication and length control. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20(4):1150–1166. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson CG, Osborn DPS, Giddings TH, Jr., Beales PL, Winey M. Basal body stability and ciliogenesis requires the conserved component Poc1. Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;187(6):905–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 Samples of each dataset studied in present study. Note; some datasets might be divided into two or more groups depending on sample phenotype.

Supplementary Table S2 All genes ranked by differential expression percentage.

Supplementary Table S3 Details about SNPs susceptibility to T2DM.

Supplementary Table S4 Details about SNPs susceptibility to obesity.

Supplementary Table S5 Ranked genes located within ± 1Mb of SNPs susceptibility to T2DM or obesity.

Supplementary Table S6 Comparison of p-values before and after adjusting by FDR.

Supplementary Table S7 Up- and down- expression of candidate genes in T2DM- and obesity-control study.