“Malignant” stroke features include a large core (>100 ml), little penumbra, and no collateral circulation, and portray a poor outcome. These authors studied patients with proximal intracranial arterial occlusions and assessed infarct core size and collateral circulation as seen on CTA. After analyzing 197 such patients, they determined that those with poor collateral grades (absent collateral circulation) had larger infarct cores, large lesions on DWI, and a poor functional outcome. Additionally, patients with poor collaterals had higher NIHSS scores at admission.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Large admission DWI lesion volumes are associated with poor outcomes despite acute stroke treatment. The primary aims of our study were to determine whether CTA collaterals correlate with admission DWI lesion volumes in patients with AIS with proximal occlusions, and whether a CTA collateral profile could identify large DWI volumes with high specificity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We studied 197 patients with AIS with M1 and/or intracranial ICA occlusions. We segmented admission and follow-up DWI lesion volumes, and categorized CTA collaterals by using a 5-point CS system. ROC analysis was used to determine CS accuracy in predicting DWI lesion volumes >100 mL. Patients were dichotomized into 2 categories: CS = 0 (malignant profile) or CS>0. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to compare imaging and clinical variables between these 2 groups.

RESULTS:

There was a negative correlation between CS and admission DWI lesion volume (ρ = −0.54, P < .0001). ROC analysis revealed that CTA CS was a good discriminator of DWI lesion volume >100 mL (AUC = 0.84, P < .001). CS = 0 had 97.6% specificity and 54.5% sensitivity for DWI volume >100 mL. CS = 0 patients had larger mean admission DWI volumes (165.8 mL versus 32.7 mL, P < .001), higher median NIHSS scores (21 versus 15, P < .001), and were more likely to become functionally dependent at 3 months (95.5% versus 64.0%, P = .003). Admission NIHSS score was the only independent predictor of a malignant CS (P = .007).

CONCLUSIONS:

In patients with AIS with PAOs, CTA collaterals correlate with admission DWI infarct size. A malignant collateral profile is highly specific for large admission DWI lesion size and poor functional outcome.

Core infarct size, quantified using admission MR imaging– DWI, is a strong predictor of functional outcome following AIS.1 Furthermore, pretreatment DWI lesion size has been shown to influence the response to both intravenous and intra-arterial therapies.2,3 Specifically, a malignant tissue profile consisting of a large pretreatment DWI lesion is recognized as a clinically useful marker for poor treatment response.3,4 However, MR imaging has limited availability in the treatment setting. Therefore, identifying surrogate CT-based markers for a malignant tissue profile would provide an important tool for treatment decision making.

Although many centers use CT perfusion to evaluate tissue viability in AIS, there are numerous challenges to this approach, including poor reliability of perfusion measurement,5 conflicting data regarding the perfusion parameter (CBV versus CBF) that best predicts core infarction,6,7 and lack of standardized protocols for acquisition, postprocessing, and analysis.8,9 CT-based evaluation of collaterals, on the other hand, offers a straightforward and promising alternative for assessing ischemic injury. The pial collateral circulation limits core infarct size by supporting penumbral tissue during acute ischemia. Multiple studies have evaluated collaterals by using CTA and have demonstrated improved tissue and clinical outcomes in patients with more robust CTA collaterals.10–12 However, because of their poor specificity, these grading systems are not particularly helpful for treatment decisions in individual patients.

We sought to determine whether CTA collaterals correlate with concurrent DWI lesion volumes and specifically whether a CTA collateral signature could identify a malignant DWI pattern with high specificity.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We retrospectively identified 204 patients with AIS with anterior circulation PAO [ICA and/or M1 occlusion] who were admitted to our emergency department between April 2003 and September 2010, and who underwent DWI and CTA within 9 hours from stroke onset. The time window of 9 hours was chosen because it is the longest time postictus where there is clinical evidence to support a beneficial treatment effect in imaging-selected patients.13 Seven patients were excluded due to poor CTA quality. We reviewed the clinical and imaging data of this cohort. Our institutional review board approved this retrospective review. The study was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant.

Image Acquisition

CTA imaging was performed using a helical scanner (LightSpeed 16 or 64; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) in the emergency department. NCCT scans were performed in helical mode (1.25-mm thickness, kV 120, mA 250) and reconstructed in the axial (5 mm thickness) and coronal (2.5-mm thickness) planes. CTA was performed during the administration of 80–100 mL of nonionic contrast agent (Omnipaque 370; Nycomed, Roskilde, Denmark), followed by 40 mL of saline, both at a rate of 4 mL/s (1.25-mm thickness, 120 kV, 300–800 mA, 0.5–0.7 seconds/rotation). Additional images were reconstructed in the axial plane at 5-mm thickness, as well as reformatted to 20-mm-thick MIPs in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. Scanning was initiated when a region of interest placed over the ascending aorta measured >75 HU (Smartprep; GE Healthcare).

MR imaging was performed in the emergency department on a 1.5T Signa whole body scanner (GE Healthcare). Our stroke MR imaging protocol included a single-shot echo planar, spin-echo DWI sequence with two 180-degree radio-frequency pulses to reduce eddy current–induced distortions. Five images/section were acquired at b = 0 seconds/mm2, followed by 5 at b = 1000 seconds/mm2 in 6 directions, for a total of 28 to 35 images/section. Imaging parameters were TR/TE of 5000/80–110 ms, FOV 22-cm, matrix 128 × 128 zero-filled to 256 × 256, 5-mm section thickness, and 1-mm gap. MR imaging was performed immediately after CTA in all cases.

Image Analysis

CTA collaterals were evaluated independently by 2 radiologists with 3 (L.C.S.S.) and 6 (A.J.Y.) years of dedicated neuroradiology experience, blinded to all clinical and imaging information except stroke side.

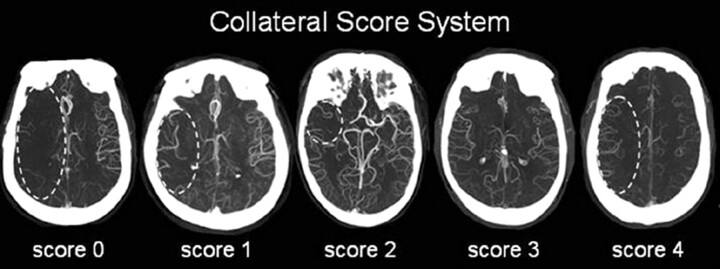

Intracranial CTA MIPs were used for grading the CS: 0 = absent collaterals in >50% of an MCA M2 branch (superior or inferior division) territory; 1 = diminished collaterals in >50% of an MCA M2 branch territory; 2 = diminished collaterals in <50% of an MCA M2 branch territory; 3 = collaterals equal to the contralateral hemisphere; and 4 = increased collaterals (Fig 1). This grading system was a modification of the one used by Tan et al,10 whose scores were based on the extent of decreased collateralization—greater than versus less than 50% of the occluded territory. Because our study examined only terminal ICA or MCA stem occlusions, 50% of the “occluded territory” could encompass as much as 150 mL of tissue, exceeding the one-third of the entire MCA territory volume that is widely regarded as the threshold above which poor outcome is highly probable. Therefore, we based our grading upon 50% of 1 MCA division (∼60–75 mL). Recent studies have supported the clinical importance of this volume threshold.1,14

Fig 1.

CS system: 0 = absent collaterals >50% of an M2 territory; 1 = diminished collaterals >50% M2 territory; 2 = diminished collaterals <50% M2 territory; 3 = collaterals equal to contralateral side; 4 = increased collaterals.

For all patients, admission DWI lesions were manually segmented based on visual assessment by 1 of the 2 readers. For 136 (69%) patients with a follow-up scan (CT or MR imaging-DWI obtained 24–72 hours after the initial scan), follow-up infarcts were manually segmented. The follow-up scans consisted of DWI in 60% (81/136) of cases and NCCT in the remaining 40%. Image analysis was performed by using a commercial software package (Analyze 8.1; AnalyzeDirect, Rochester, Minnesota).

Statistical Analysis

Patients were initially stratified into the 5 CS categories (0–4). Interrater agreement for CS grading was assessed using the κ statistic. A Spearman correlation coefficient was computed for CS versus admission DWI lesion volume, and compared with the correlation between NIHSS score and DWI volume. Univariate analyses comparing collateral categories consisted of ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis (normally distributed continuous variables), Kruskal-Wallis (ordinal data), and χ-square (categoric variables) testing. Normality was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

ROC curves were used to determine the test characteristics of the collateral score in determining admission DWI lesion volumes >70 mL, 80 mL, and 100 mL, as well as to compare the test characteristics of the CS to those of the NIHSS score for the prediction of baseline DWI volume >100 mL.

These volume thresholds were chosen based on previous work demonstrating that lesion volumes between 70–100 mL were predictive of poor outcome or of a clinically malignant profile.1,4,14,15 Additional ROC analyses were performed for follow-up infarct volumes and dichotomized 3-month mRS. For these analyses, the cohort was divided into patients receiving intravenous or intra-arterial therapy and untreated patients.

Finally, patients were dichotomized into CS = 0 (malignant profile) versus CS >0. For univariate analysis, we used the Student t test (normally distributed data), Mann-Whitney test (ordinal data), and χ-square test (categoric data). An ordinal logistic regression identified the independent variables associated with admission CS, and a multiple binary logistic regression identified the independent predictors of the malignant collateral profile. SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) and MedCalc 11.5.1.0 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) software were used to perform the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was taken at the P < .05 level.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Univariate Analysis

The mean patient age was 67 ± 17 years. Forty-seven percent of subjects were women. The median admission NIHSS score was 15 (12–19). Forty-nine percent of strokes were left-sided. The mean admission systolic blood pressure and blood glucose were 151 ± 32 mm Hg and 141 ± 52 mg/dL. The mean baseline DWI lesion volume was 48 ± 62 mL.

Forty-nine of 197 patients (25%) were treated with IV tPA alone, 82 (41.6%) with IAT with or without IV tPA, and 66 (33.5%) did not receive any reperfusion therapy. At 3 months, the median mRS was 4 (2–6). Fifty-five of 172 patients (28%) had good outcome (mRS ≤2) and 44 (26%) died.

Of the 197 study patients, 22 (11%) were categorized as CS = 0, 40 (20.3%) as CS = 1, 67 (34%) as CS = 2, 42 (21.3%) as CS = 3, and 26 (13%) as CS = 4. Kappa interrater agreement was 0.76 (P < .001) for the full CS and 0.83 (P < .001) for the binary score (CS = 0 versus 1–4). There was a significant negative correlation between the collateral score and baseline DWI lesion volume (ρ = −0.54, 95% CI = −0.629 to −0.429, P < .0001), which was larger in magnitude than the correlation for admission NIHSS score versus DWI volume (ρ = 0.38, P = .07 for comparison).

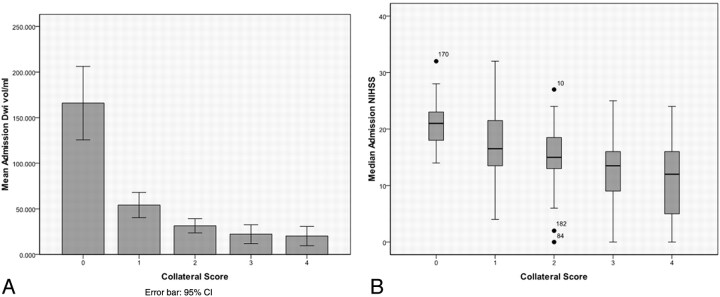

The admission DWI lesion volumes and NIHSS scores were significantly different between collateral categories (both P < .001), with both demonstrating an inverse relationship (Fig 2). Post hoc analysis revealed that mean DWI lesion volumes were significantly larger for CS = 0 than any other score, while patients with a CS = 1 had significantly larger volumes only versus patients with scores of 3–4. Median admission NIHSS in CS = 0 patients was significantly higher than in patients with scores of 2–4, and CS = 1 patients had significantly higher NIHSS scores versus patients with scores of 3–4. Admission DWI lesion volumes and NIHSS scores were not significantly different between the remainder of the CS categories. When analyzing the full collateral score versus 3-month mRS, patients with higher CS tended to have better outcome (P = .07).

Fig 2.

There is progressive decrease in admission (A) DWI lesion volumes (P < .001) and (B) NIHSS (P < .001) as CS increases. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

In the multivariate analysis, admission DWI lesion volume (P < .001) and NIHSS score (P = .007) were the only independent variables associated with admission collateral score.

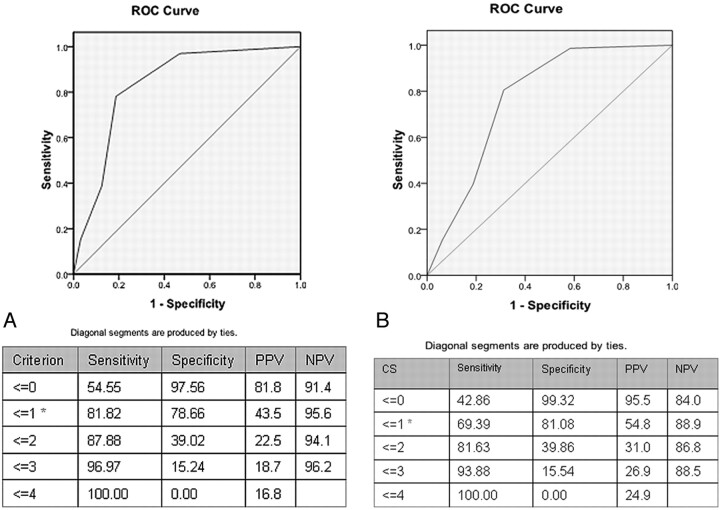

ROC Analysis

ROC analysis demonstrated good performance of the collateral score for determining admission DWI lesion volumes >100 mL, 80 mL, and 70 mL, with an AUC = 0.84, 0.80, and 0.78, respectively (all Ps <.001; Fig 3). Comparing the test characteristics for the prediction of baseline DWI volume >100 mL, the CTA collateral score had a significantly greater AUC than the NIHSS score (0.83 versus 0.68, P = .03 for comparison).

Fig 3.

ROC curves for CS versus DWI volumes (A) >100 mL (AUC = 0.84, P < .001) and (B) >70 mL (AUC = 0.78, P < .001). Tables display test characteristics for various scores, including optimal operating points (*), and positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV).

For untreated patients, the collateral score also performed well for determining follow-up DWI lesion volumes >100 mL, 80 mL, and 70 mL, with AUC = 0.82, 0.83, and 0.84, respectively (all Ps <.001). For treated patients, the collateral score could only determine follow-up lesion volumes >70 mL (AUC = 0.63, P = .02) but not lesion volumes >80 mL (AUC = 0.61, P = .06) or >100 mL (AUC = 0.56, P = .33).

Similarly, ROC analysis revealed that the collateral score predicted 3-month functional independence (mRS 0–2) in untreated patients (AUC = 0.80, P < .01), but not in those who underwent therapy (AUC = 0.58, P = .19).

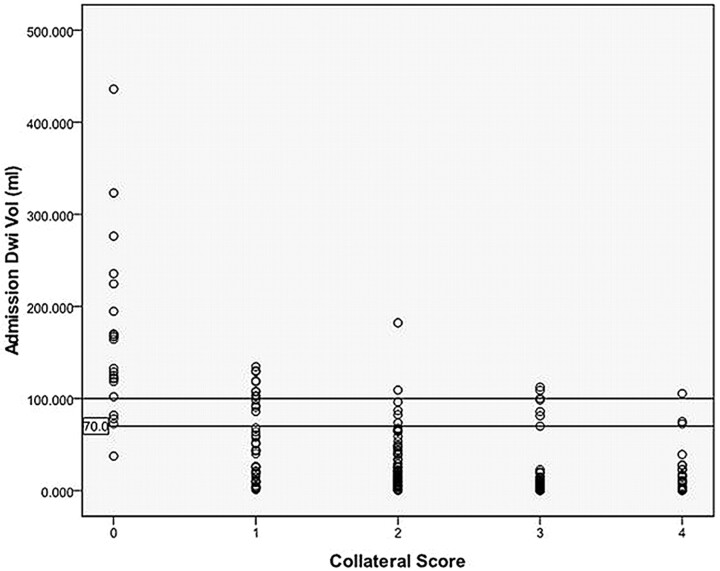

Characterizing a Malignant CTA Collateral Profile

A collateral score of zero was defined as a malignant profile because it maximized specificity for a large baseline DWI lesion size. CS = 0 was 97.6% specific and 54.5% sensitive for a DWI lesion volume >100 mL, and 99.3% specific and 42.9% sensitive for a DWI volume >70 mL (Figs 3 and 4). Of the 32 patients with lesion volumes >100 mL, 17(53%) had a collateral score of 0; 9 (28%) had a collateral score of 1; and 6 (19%) had a collateral score ≥2. Of the 48 patients with lesion volumes >70 mL, 20 (42%) had a collateral score of 0; 13 (27%) had a collateral score of 1; and 15 (31%) had collateral scores ≥2.

Fig 4.

Scatterplot of DWI volumes versus CSs. Most CS = 0 patients have lesion volumes >70–100 mL (horizontal lines). There is great overlap between the other CS categories.

CS = 0 patients had significantly larger mean admission DWI lesion volumes (165.8 mL versus 32.7 mL, P < .001) as well as higher median admission NIHSS scores (21 versus 15, P < .001). The remainder of the baseline clinical variables did not differ between the 2 groups (Table 1).

Table 1:

Univariate analysis for dichotomized collateral score

| Collateral = 0 | Collateral > 0 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 22 | 175 | |

| Age | 71 ± 15 | 66 ± 17 | 0.25 |

| Sex (female) | 41% | 36% | 0.88 |

| Side of stroke (left side) | 59% | 47% | 0.44 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 149 ± 63 | 140 ± 50 | 0.56 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 153 ± 125 | 150 ± 33 | 0.73 |

| NIHSS score | 21 (17–26) | 15 (11–18) | <0.001 |

| DWI lesion volume (ml) | 165.8 ± 19 | 32.7 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| 3-month mRS | 5 (3–6) | 3 (1–5) | 0.022 |

| Dependent or deceased (mRS >2) | 95.5% | 64.0% | 0.003 |

| Treatment (IV and/or IA) | 63.6% | 67.2% | 0.74 |

Note:—Results are expressed in mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or percentages.

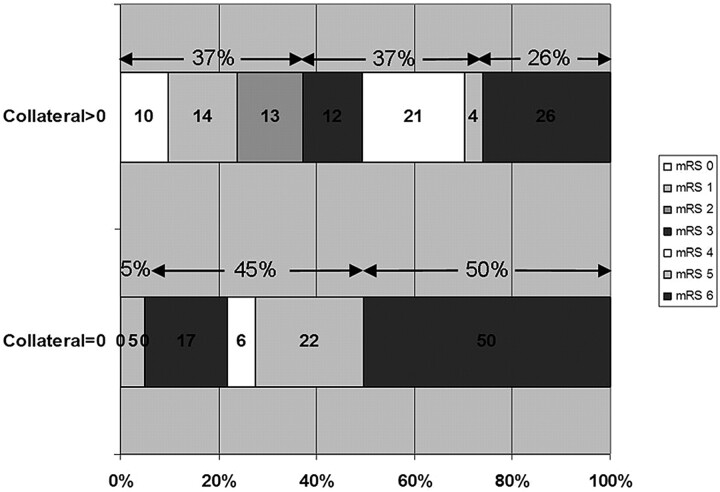

Of the 22 patients with CS = 0, 13 (59%) were treated with IV tPA, 1 (5%) received IAT, and 8 (36%) were untreated. For all treatment modalities, patients with a malignant collateral profile had a higher percentage of poor outcome than CS >0 patients (Table 2). Overall, CS = 0 patients had a higher median 3-month mRS versus those with CS >0 (5 versus 3, P = .02), and were more likely to be dead or dependent (95.5% versus 64.0%, P < .01; Fig 5). Multiple logistic regression showed NIHSS score to be the only independent predictor of CS = 0 (odds ratio = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.66–0.95, P = .01).

Table 2:

Outcome by treatment and by collateral score

| Collateral = 0 | Collateral > 0 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment (# patients) | 8 | 45 | |

| Good outcome (mRS ≤ 2) | 0% | 35.6% | 0.044 |

| Poor outcome (mRS > 2) | 100% | 64.4% | |

| IV treatment only (# patients) | 13 | 30 | |

| Good outcome (mRS ≤ 2) | 7.7% | 50.0% | 0.008 |

| Poor outcome (mRS > 2) | 92.3% | 50.0% | |

| IA treatment ± IV (# patients) | 1 | 75 | |

| Good outcome (mRS ≤ 2) | 0% | 30.7% | 0.507 |

| Poor outcome (mRS > 2) | 100% | 69.3% |

Fig 5.

Distribution of mRS scores between patients with CS = 0 versus >0.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that in patients with AIS with terminal ICA or proximal MCA occlusions, the degree of collateral circulation on admission CTA correlates with the admission DWI lesion volume. Moreover, using a simple and reliable grading system, we have identified a malignant CTA collateral profile that is highly specific for patients with large baseline infarcts at high risk for poor long-term outcome. Our CTA collateral score of zero has >95% specificity for admission DWI lesion volume >100 mL and a >90% rate of 3-month death or dependency. These findings are relevant for clinical practice because CTA is more widely available in the emergency setting than MR imaging–DWI. In addition, CTA collateral grading may provide a useful alternative for patients ineligible for MR imaging.

Conventional angiography is the reference standard test for collateral evaluation because it incorporates the timing of collateral filling.16 However, its major drawbacks include its invasiveness and the time required to collect this information. Recent studies have supported the prognostic utility of CT angiography for noninvasive collateral grading in the setting of proximal occlusions.11,12 Using different grading schemes, these studies have demonstrated that patients with greater CTA collaterals have better functional outcomes and smaller final infarct volumes. However, the clinical utility of these grading systems is limited to population-level prognostication, making them more suitable for risk modeling rather than for clinical decision making in individual patients.

By characterizing a malignant CTA collateral profile, we have demonstrated that CTA collateral grading may be able to impact treatment decisions by identifying patients who are at high risk for having a large pretreatment infarct volume and therefore may be unlikely to benefit from revascularization therapy. Our patients with a malignant pattern appear similar to corresponding populations in other AIS studies. In the DEFUSE study,4 “malignant profile” patients were defined as those with baseline DWI lesion ≥100 mL and/or PWI lesion ≥100 mL with ≥8 seconds of Tmax (time at which the tissue residue function reaches its maximum) delay. This group constituted 8.1% of the DEFUSE cohort, and had a mean age of 68.3 years, median baseline NIHSS score of 18.5, and 83% rate of 30-day mRS >2. In 1 study of intra-arterial therapy,3 “futile” patients were defined as those with baseline DWI lesion >70 mL. These patients represented 17.6% of the study population, which is higher than in DEFUSE because of the requirement for proximal arterial occlusion, and had mean age of 57.8 years, median NIHSS score of 21, and 100% rate of 90-day mRS >2. In comparison, our patients with a CTA CS = 0 constituted 11.1% of the study population, had mean age of 71.4 years, median baseline NIHSS score of 21, and 92% rate of 3-month mRS >2.

Interestingly, a recently published work by Puetz et al proposed another CTA-based imaging signature for identifying a malignant stroke population.17 In that study, the authors examined a 20-point score that combined the CTA source image ASPECT score and clot burden. Among 114 anterior circulation stroke patients treated with IV tPA within 3 hours, they found 24 patients (21%) with a combined score ≤10 (malignant profile), of whom 1 (4%) was independent at 3 months and 50% of whom died. Despite very similar clinical outcomes between our method and theirs, our approach appears more straightforward and probably provides a faster real-time assessment. Furthermore, our approach may be more suitable for selecting patients for intra-arterial therapy, where clot burden is less of a hindrance to recanalization than with IV tPA.

Even though our CTA collateral score correlated with admission DWI lesion size, there was significant overlap in lesion volumes for collateral scores greater than zero. This prevented us from identifying a benign collateral score that would have a high (>90%) specificity for a small (<70 mL) admission infarct size.

The correlation between our CTA collateral score and 3-month mRS demonstrated a trend toward statistical significance. When analyzing patients by treatment status, the collateral score predicted dichotomized functional outcome and final infarct size only for untreated patients. This finding is a matter of controversy within the literature. In a recent study, Bang et al found that good angiographic collateral status was associated with higher recanalization rates after intra-arterial therapy and less infarct growth after recanalization.18 Similarly, Angermaier et al demonstrated that CTA collateral grade was an independent predictor of final infarct volume in stroke patients treated with endovascular therapy.19 On the other hand, Rosenthal et al reported that CTA collaterals had a positive impact on the outcomes of patients who did not achieve complete recanalization, and no impact in patients who were completely recanalized.20 Furthermore, Lima et al found a greater beneficial effect of collateral status in untreated patients.11 Further studies are needed to clarify this question. However, it is intuitive that, in untreated patients (with presumably lower rates of recanalization), the degree of collateral circulation should have a more significant role in determining tissue fate and clinical outcome.

Our study limitations include those inherent in a retrospective design. As such, recanalization status, a significant predictor of stroke outcome, was only available for a small fraction of our patients, precluding its entrance into our analysis. However, this would not be expected to affect our findings with respect to pretreatment infarct size and baseline NIHSS score. Nevertheless, our findings require prospective validation before they are used for decision making in the clinical setting. In addition, we recognize that our malignant CTA collateral profile has a low sensitivity for identifying large admission core infarcts. However, this would be a major concern if this approach were used as the primary means of selecting patients for revascularization therapy. Rather, we simply sought to identify a clinically useful CTA collateral sign that would indicate a very large DWI volume with high specificity. If validated, this sign would allow one to confidently exclude patients from treatment based on their high likelihood of having a bad outcome, and it could supplement other forms of parenchymal evaluation. We are not stating that patients who have a collateral grade higher than zero will necessarily have a DWI volume <100 mL and would benefit from treatment. Collateral scores of 1 to 4 are too nonspecific to be used clinically for characterizing infarct volumes.

Conclusions

In patients with AIS with PAOs, CTA collateral grade is inversely correlated with admission DWI lesion size. Patients with absent collaterals in >50% of 1 MCA M2 division territory have a very high likelihood of having a DWI lesion >100 mL and a poor clinical outcome. If validated, these findings have clinical relevance for hospitals where emergent access to MR imaging is limited and for patients who are ineligible to undergo MR imaging.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- ASPECT

Alberta Stroke Program Early CT

- AUC

area under the ROC curve

- CS

collateral score

- IAT

intra-arterial revascularization therapy

- M1

middle cerebral artery stem

- M2

middle cerebral artery second order branch

- MIP

maximum intensity projection

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- PAO

proximal artery occlusion

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

Footnotes

This work was supported by an NIH SPOTRIAS Network grant (P50 NS051343), an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant (R01 HS11392), and the MGH Clinical Research Center (No. 1 UL1 RR025758-01) Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources). A.J.Y. and R.G.G. receive research support from Penumbra, Inc. M.H.L. receives research support from GE Healthcare and is Consultant to Co-Axia, GE Healthcare, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosures: Albert Yoo—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: Penumbra, Inc.* Joshua Hirsch—UNRELATED: Consultancy: CareFusion, Phillips, Comments: Vertebral Augmentation (Phillips—Participated in focus group of NI specialists for NI suites of the future; CareFusion—participated on NextGen team for product development); Royalties: CareFusion, Comments: as above; Stock/Stock Options: Intratech, NFocus, Nevro, Comments: Development stage companies that are working on NI products (IntraTech and N-Focus) and nerve imaging (Nevro). Karen Furie—RELATED: Grants: PHS.* Raul G. Nogueira—UNRELATED: Board Membership: Concentric Medical, eV3 Neurovascular, Coaxia; Consultancy: Concentric Medical, eV3 Neurovascular, Coaxia. Michael Lev—RELATED: Grant: NINDS SPOTRIAS,* GE Healthcare,* Comments: Research support; UNRELATED: Consultancy: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, GE Healthcare, Comments: < $10K; Grants/Grants Pending: DOD,* NBIB;* Royalties: Q&A color review of neuroimaging, Comments: < $1K, Stock/Stock Options: GE, Comments: Own common stock < $10K. (*Money paid to institution).

References

- 1. Yoo AJ, Barak ER, Copen WA, et al. Combining acute diffusion-weighted imaging and mean transmit time lesion volumes with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score improves the prediction of acute stroke outcome. Stroke 2010;41:1728–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parsons MW, Christensen S, McElduff P, et al. Pretreatment diffusion- and perfusion-MR lesion volumes have a crucial influence on clinical response to stroke thrombolysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30:1214–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yoo AJ, Verduzco LA, Schaefer PW, et al. MRI-based selection for intra-arterial stroke therapy: value of pretreatment diffusion-weighted imaging lesion volume in selecting patients with acute stroke who will benefit from early recanalization. Stroke 2009;40:2046–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Albers GW, Thijs VN, Wechsler L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging profiles predict clinical response to early reperfusion: the diffusion and perfusion imaging evaluation for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE) study. Ann Neurol 2006;60:508–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiorella D, Heiserman J, Prenger E, et al. Assessment of the reproducibility of postprocessing dynamic CT perfusion data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:97–107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, et al. Perfusion-CT assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke 2006;37:979–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bivard A, McElduff P, Spratt N, et al. Defining the extent of irreversible brain ischemia using perfusion computed tomography. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;31:238–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wintermark M, Albers GW, Alexandrov AV, et al. Acute stroke imaging research roadmap. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:e23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamalian S, Maas MB, Goldmacher GV, et al. CT cerebral blood flow maps optimally correlate with admission diffusion-weighted imaging in acute stroke but thresholds vary by postprocessing platform. Stroke 2011;42:1923–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan JC, Dillon WP, Liu S, et al. Systematic comparison of perfusion-CT and CT-angiography in acute stroke patients. Ann Neurol 2007;61:533–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lima FO, Furie KL, Silva GS, et al. The pattern of leptomeningeal collaterals on CT angiography is a strong predictor of long-term functional outcome in stroke patients with large vessel intracranial occlusion. Stroke 2010;41:2316–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tan IY, Demchuk AM, Hopyan J, et al. CT angiography clot burden score and collateral score: correlation with clinical and radiologic outcomes in acute middle cerebral artery infarct. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:525–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hacke W, Albers G, Al-Rawi Y, et al. The Desmoteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke Trial (DIAS): a phase II MRI-based 9-hour window acute stroke thrombolysis trial with intravenous desmoteplase. Stroke 2005;36:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanák D, Nosal V, Horak D, et al. Impact of diffusion-weighted MRI-measured initial cerebral infarction volume on clinical outcome in acute stroke patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion treated by thrombolysis. Neuroradiology 2006;48:632–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomalla G, Hartmann F, Juettler E, et al. Prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction by magnetic resonance imaging within 6 hours of symptom onset: a prospective multicenter observational study. Ann Neurol 2010;68:435–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2003;34:e109–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Puetz V, Dzialowski I, Hill MD, et al. Malignant profile detected by CT angiographic information predicts poor prognosis despite thrombolysis within three hours from symptom onset. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;29:584–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, et al. Collateral flow predicts response to endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011;42:693–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Angermaier A, Langner S, Kirsch M, et al. CT-angiographic collateralization predicts final infarct volume after intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;31:177–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenthal ES, Schwamm LH, Roccatagliata L, et al. Role of recanalization in acute stroke outcome: rationale for a CT angiogram-based “benefit of recanalization” model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1471–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]