Summary

Cells reside in mechanically rich and dynamic microenvironments, and the complex interplay between mechanics and biology is widely acknowledged. Recent research has yielded insights linking the mechanobiology of cells, human physiology, and pathophysiology. In particular, we have learned of the cell’s astounding ability to sense and respond its mechanical microenvironment. This seemingly innate behavior of the cell has driven efforts aimed to characterize precisely the cellular behavior from a mechanics viewpoint. Here we present an overview of technologies used to probe cell mechanical and material properties, how they have led to the discovery of seemingly strange cellular mechanical behaviors, and their influential role in health and disease; including asthma, cancer, and glaucoma. The properties reviewed here have implications in physiology and pathology and raise questions that will fuel research opportunities for years to come.

Keywords: cell mechanics, plithotaxis, soft glassy materials, reinforcement, fluidization, asthma, glaucoma, cancer

Mechanics are part of our everyday life. For the father teaching his son to catch a ball as for the commuter running to catch a train, cells cooperate to allow bones, tissues, and other structures to perceive and respond to mechanical force. Throughout their lifetime, cells experience mechanical stimulation. Depending on the cell’s location, such stimuli may be in the form of tension, compression, or shear, and may be static or cyclic [1–4]. As a result, cells have evolved the ability to sense and respond to their local microenvironment [5–8]. Such behavior has intrigued scientists and inspired efforts aimed at characterizing these behaviors and their underlying mechanisms. While many approaches exists [3 9–11], we will primarily examine techniques used to define the physical forces a cell exerts on its substrate and upon neighboring cells, and the techniques used to characterize cellular material properties.

Measuring the cell’s mechanical properties

Recent works have highlighted cell contractility and its importance in a myriad of biological processes including cell migration, embryogenesis, morphogenesis, metastasis, and wound healing [12–17]. For the adherent cell to perform such tasks the ability to contract and exert tractions on its surroundings is requisite. Cellular contractility is a mechanism that consists of complex interactions between the substrate, adhesion molecules, cytoskeletal elements and molecular motors. To measure contractile forces or tractions at the cellular level we use traction force microscopy [17–19]. In general, tractions are obtained by measuring displacement fields generated by a single cell or a group of cells adherent upon a ligand-coated, flexible substrate (Figure 1A). This flexible substrate is the underlying, supporting scaffold upon which cells are adhered to through basal transmembrane proteins including integrins and syndecans. Embedded within that substrate are fluorescent markers that allow for the measurement of substrate deformation through conventional microscopy methods. An alternative to this approach consists of using microfabricated, elastomeric microposts [20,21]. Using this method, the deflection caused by an adherent cell on vertically aligned microposts can be directly measured and used to deduce tractions [20, 21].

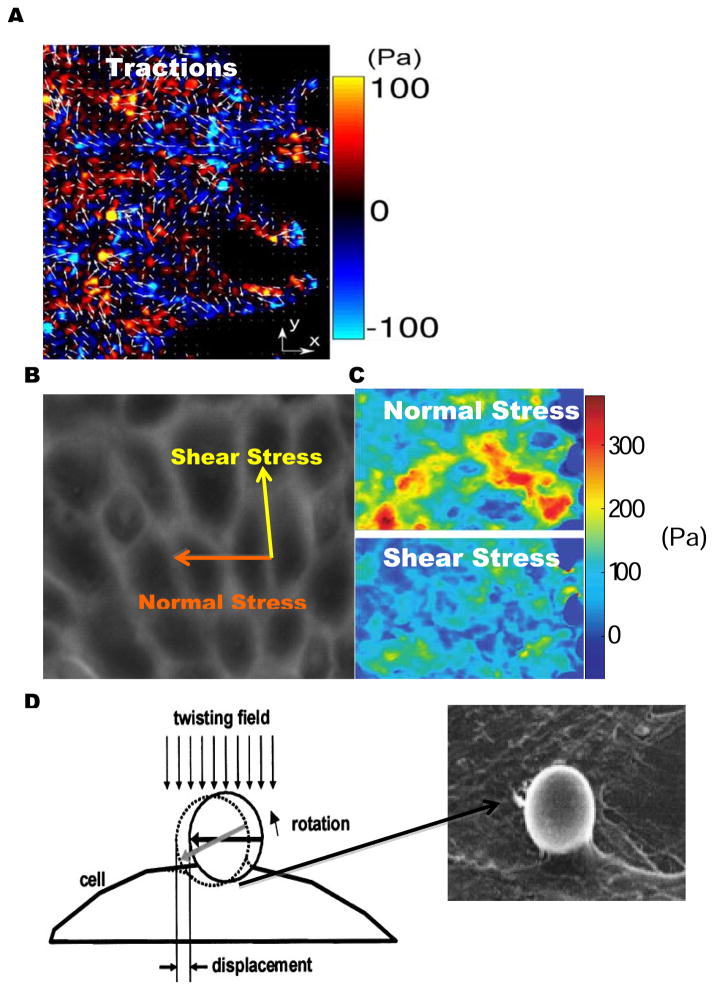

Fig. 1. Cell mechanics methodologies.

(A) Color-coded map of traction force (x-component) overlaid with arrows depicting complete traction vector (x and y component) of migrating monolayer using traction force microscopy. (B) Utilizing monolayer stress microscopy we are now able to determine the normal and shear intercellular stress components within a monolayer of cells and (C) observe their corresponding spatial distributions. Cells within a monolayer are generally observed to have a rugged stress landscape and be mainly in tension. (D) OMTC is yet another useful technique used to probe cell material properties by attaching a ligand-coated magnetic bead to cell surface receptors and applying a torque to the bead with an external magnetic field. Adapted from refs. 14,32

Having introduced traction microscopy we now extend our discussion to a new technique recently developed in our lab, monolayer stress microscopy (MSM) [14,22]. Extending our analysis from a single cell to a cell monolayer, we know that each cell is connected to its neighbor through cell-cell junctions. While the role of the cell-cell junction as both an active and a passive mechanosensor has been established, it was not until recently that its ability to establish and maintain intercellular forces and resultant stresses was discovered. The magnitude of intercellular forces regulates cell-cell contact size [23] and is dependent on substrate stiffness and Rho kinase activity [24]. Complementary experiments also revealed intercellular forces to be independent of cell size and morphology [20]. Information on the spatial and temporal characteristics of intercellular forces within a motile monolayer did not exist, however, until the development of MSM. The intercellular stress is defined as the local intercellular force per unit area of cell-cell contact [14] and is composed of two components: a normal stress defined as the stress acting perpendicular to the local intercellular junction, and shear stress defined as the stress acting parallel to the local intercellular junction (Figure 1B). With MSM we are now able to measure the normal and shear intercellular stress distributions within a monolayer. (Figure 1C and D). While traction force microscopy and monolayer stress microscopy provide two excellent approaches to measure tractions and intercellular stress, optical magnetic twisting cytometry provides yet another useful technique to measure cell material properties.

Optical magnetic twisting cytometry (OMTC) is used to measure cell stiffness and has proven to be useful in understanding the mechanisms of force transmission across the cell membrane [25]. In short, OMTC consists of using ligand-coated, magnetic spheres that are conjugated to cell surface receptors and exposed to a magnetic field, producing twisting torques of various magnitudes (Figure 1D). Conventional microscopy methods are used to track bead displacements, which are in turn related to various cell mechanical properties including stiffness, friction, and hysteresivity. OMTC is a useful tool in determining the effects of various chemical and mechanical perturbations on multiple cell material properties.

Dynamic mechanical properties of the cell

Fluidization/reinforcement

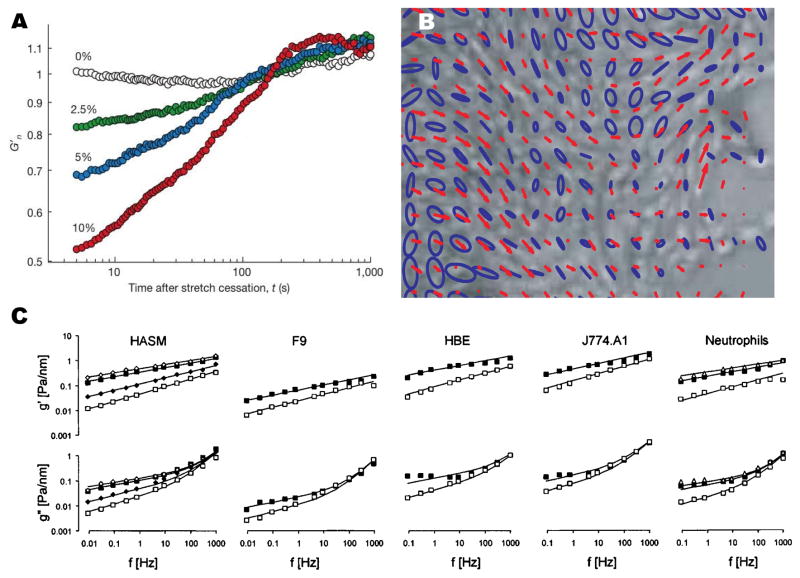

Cells have thoroughly demonstrated their ability to sense and respond to mechanical stretch. A well-documented response to uniaxial stretch is reinforcement [26,27]. Reinforcement describes a phenomenon in which the cytoskeleton increases stiffness by recruiting various biomolecules in response to stretch, exhibiting an active strain-stiffening behavior along with associated structural changes [28]. In contrast to the phenomenon of reinforcement, cells have been shown to fluidize in response to stretch. Additional factors including actin crosslinking proteins, intracellular calcium levels, and actin fiber density and alignment are also known to contribute to cytoskeletal stiffness, reflecting the biochemical and mechanical synergy needed for cells to respond to stretch. To address these seemingly disparate results, we used OMTC to measure cell mechanical properties after various periods of stretch [29]. Following stretch, cell stiffness first rapidly and significantly decreased and then gradually increased over time, eventually returning to baseline stiffness levels; suggesting that cells in fact fluidize and resolidify in response to stretch [29] (Figure 2A). These behaviors persisted in the presence of several different chemical perturbations, with only slight changes in magnitude and temporal scales [29]. ATP depletion of the cells revealed resolidification to be ATP-dependent [29]. Our findings indicated that among mammalian cells resolidification and fluidization are universal responses [29]. We further probed fluidization by monitoring cell contractility using a method we developed called Cell Mapping Rheometry (CMR) [28]. CMR uses a novel punch-indentation system to induce biaxial or uniaxial homogeneous deformations on cells cultured on a flexible substrate [28]. Using CMR we once again observed stretch-induced fluidization, corroborating results found previously using OMTC [28,29].

Fig. 2. Emergent cell mechanical properties.

(A) Cells have been observed to fluidize and reinforcement in response to stretch regardless of stretch magnitude. (B) Plithotaxis describes the phenomenon of cells to migrate such as to minimize shear stress on their cell-cell junctions, depicted in the alignment between velocity vectors (red line) with the principal stress orientation (blue ellipses). (C) Multiple cell types exposed to a series of biological perturbations have all been observed to exhibit a power law behavior, a characteristic of soft glassy materials. Adapted from refs. 14, 29, 32

Plithotaxis

Shifting our attention from single cells to cell monolayers, we now focus on an emergent phenomenon describing collective cellular migration: plithotaxis [14]. Cellular migration is an essential step for many physiological processes including morphogenesis, wound healing, and regeneration [12,15] and has recently been implicated in pathological processes such as cancer metastasis [15]. Through monolayer stress microscopy we reported for the first time high-resolution normal and shear intercellular stress maps, revealing stress distributions that were extremely heterogeneous. In addition, the velocity vectors of migrating cells were found to correlate with the maximum normal stresses (or minimal shear stresses), implying that cells migrate in a direction that minimizes shear stress on its cell junctions, a phenomenon we have termed plithotaxis [14] (Figure 2B). Plithotaxis represents the first physical explanation of collective cellular migration and was found to be inhibited by calcium chelation and anti-cadherin antibodies, suggesting cells must be physically linked together by cell-cell junctions to migrate via plithotaxis [14].

Soft glassy materials

Stretch-induced fluidization and reinforcement as well as plithotaxis lead to the surprising conclusion that cells are comparable to a class of materials in physics known as soft glassy materials (SGMs). SGMs are ubiquitous in nature and include colloidal suspensions, pastes, foams, and slurries [30]. In general SGMs are known to possess the following mechanical characteristics: 1) they are soft (young’s modulus in the vicinity of 1 kPa), 2) they exhibit “scale free” dynamics, and 3) they have frictional stresses that are proportional to their elastic stresses, with a constant of proportionality known as the hysteresivity, η (where η is on the order of 0.1) [30,31]. SGMs can also undergo a phase transition between solid-like and liquid-like states [30]. Initial evidence that cells are analogous to SGMs was provided by Fabry et. al., where multiple cell types were reported to exhibit a scaling law behavior that governs their elastic and frictional properties over a wide range of temporal scales and biological conditions [32] (Figure 2 C). The cell’s elastic and frictional properties were later observed to not only exhibit a scaling law behavior, but to be scale free as well [29]. Further supporting this concept was our finding that single cells subjected to osmotically-induced compressive stress to become much more solid-like, reflecting a “phase transition” from a fluid to a solid state [33]. MSM revealed intercellular stress cooperativity to become enhanced over greater cell distances when comparing intercellular stress transmission to increasing cell density over time [14], reflecting an increase in the dynamic heterogeneity of intercellular stress as cell density increased. Complementary to intercellular force cooperativity, cell migration velocity has been observed to decrease as cell density increased, a behavior remarkably similar to a glassy system transitioning from a liquid to a solid phase [34,35]. While cells do exhibit characteristics similar to SGMs, the cell has been well documented to be orders of magnitude more complex then any other material currently known to be a SGM. Therefore the classification of cells as SGMs should be used solely as a physical observation only.

Cell mechanics and human health

Asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness

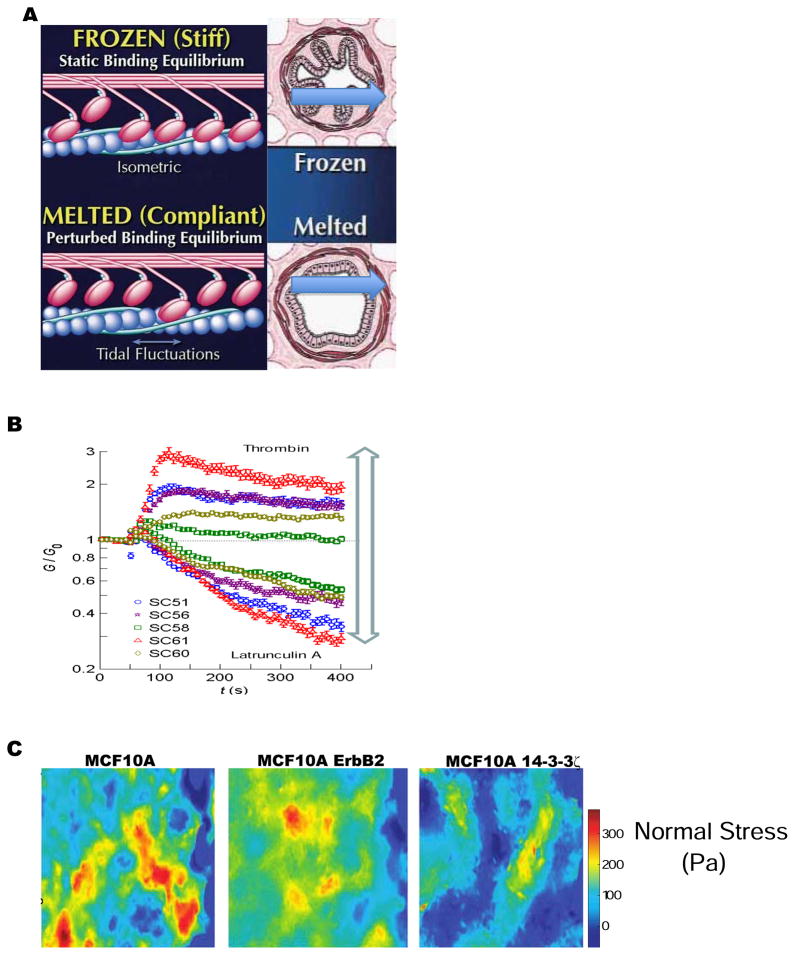

Having completed an overview of techniques used to probe cell mechanical properties and the behaviors elucidated from these techniques, we now illustrate how these findings provide insight into various facets of human health from normal physiology to pathophysiology, including asthma, glaucoma, and cancer. Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the lung most commonly characterized by airways that constrict too easily (hypersensitivity) and too much (airway hyperresponsiveness or AHR) [36,37]. AHR in particular is known to be the main cause of morbidity and mortality in asthmatics. To date, the mechanisms behind AHR remain largely unexplained. Many have hypothesized that the primary cause of AHR is an increase in airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass observed in asthma; yielding a remodeled airway with a compromised ability to perform deep inspirations (DI), the most potent known bronchodilator [36,38]. More recent work has shown that moderate bronchoconstriction even in the absence of airway inflammation can drive airway remodeling, underscoring the importance of controlling ASM constriction [39]. However, much of the modeling and experimentation in the past has assumed static mechanical equilibrium, while more recent work has demonstrated AHR is driven by dynamic phenomena, underscoring the importance of studying ASM in systems that include dynamic equilibrium [36]. To shed light on the mechanism of AHR, we isolated sheep tracheal smooth muscle strips and exposed them to controlled dynamic physiological and pathophysiological loading regimes to simulate in vivo normal and asthmatic airways [36]. Normal airways subjected to DI dilated and constricted as expected from a normal in vivo setting; however the much thicker, asthmatic airways subject to DI not only failed to dilate, but in fact constrict further. Later single cell studies conducted by our lab complemented our tissue studies [29] leading us to propose that in normal airways stretch of ASM from DI fluidizes the cytoskeleton (CSK) since load fluctuations induced on the ASM by DI induces periodic attachment and detachment events between myosin and actin [40], relaxing the muscle. In asthma, however, actin-myosin contraction is perturbed as there are far more attachment events then detachment events. In short at any given time more myosin is attached to actin, yielding a much stiffer ASM. A stiffer ASM results in less stretch during DI (as the muscle is less compliant), causing further stiffening as fluidization is blocked. This vicious cycle ultimately culminates with the collapse of the CSK, and therefore airway smooth muscle, into a frozen state [40]. The abnormal airway cannot respond to DI as it is too stiff to deform and fluidize (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. Bridging the gap between cell mechanics and health.

(A) In asthma the ability of the ASM to properly fluidize and resolidfy at will is disturbed as actin-myosin contractility is abnormal since more myosin remains attached to actin filaments at any given time, resulting in the airway being in a “frozen” state. However, in normal ASM less myosin is attached to actin filaments, allowing the airways to more readily deform at will, representing a “melted” state. (B) Schlemm’s canal cells treated with drugs known to decrease or increase aqueous humor outflow resistance surprisingly had equivalent effects on cell stiffness, providing possible therapeutic opportunities for sufferers of glaucoma. (C) The normal stress distribution of the MCF10A breast cancer cell line over-expressing the oncogenes ErbB2 (HER-2/Neu) or 14-3-3ζ, or vector (control) were observed to be remarkably distinct among one another. Cell lines expressing each oncogene reflected contrasting epithelial (ErbB2 (HER-2/Neu)) and mesenchymal (14-3-3ζ) cell behaviors. Adapted from refs. 14, 40

Glaucoma

A leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world is glaucoma [41]. In most cases, vision loss is associated with partial blockage of aqueous humor drainage from the eye, resulting in abnormally high intraocular pressure [42]. Unfortunately the underlying mechanism of this abnormal fluid drainage is poorly understood [43]. The aqueous humor is known to pass mainly through the trabecular meshwork and then through pores formed in the endothelium of the Schlemm’s canal (SC). The SC experiences an intense pressure gradient, which dramatically deforms the SC and potentially contributes to the formation of pores. SC cells therefore reside in a uniquely stressful mechanical environment, leading us as well as others to hypothesize that SC stiffness may modulate aqueous humor outflow resistance [43]. Initial SC endothelial cell stiffness measurement using atomic force microscopy revealed cell stiffness to not be qualitatively different from endothelial cells from other anatomic sites [44]. However the relationship between SC stiffness and aqueous humor outflow resistance remained unanswered. To address this Zhou et al. used drugs known to change the outflow resistance of perfused eyes and tested their effect on the stiffness of SC cells using OMTC [45]. Interestingly, drugs known to increase outflow resistance through the SC caused SC cell stiffness to increase, while drugs known to decrease outflow resistance caused cell stiffness to decrease (Figure 3B). These data support the idea that the SC endothelial cell can modulate outflow resistance. Pathologically high outflow resistance could potentially arise as a consequence of high SC cell stiffness, which can potentially serve as a therapeutic target for glaucoma treatment. Indeed, drugs targeting cytoskeleton and Rho kinase pathway are currently in clinical trials for lowering intraocular pressure [46].

Cancer

Cancer is among the leading causes of mortality in the world. Cancer is most commonly characterized by uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells and tumor metastasis. Recent research has revealed collective cellular migration to be related to this devastating disease [15], providing an excellent opportunity to examine cell migration in the context of cancer using MSM. Using the MCF10A breast cancer cell line, we compared the migratory behavior of cells over-expressing the oncogenes ErbB2 (HER-2/Neu) or 14-3-3ζ, and control cells. ErbB2 is overexpressed in 20 – 80% of tumors and this overexpression is especially prominent in early stages of breast cancer [47,48]. Additionally, ErbB2 disrupts tight junctions and epithelial monolayer polarity. On the other hand, 14-3-3ζ is overexpressed in advanced stages of cancer and known to enhance anchorage independent growth and inhibit stress-induced apoptosis [49]. Control cells migrated via plithotaxis [14]. However, cells overexpressing ErbB2 also exhibited plithotaxis-guided migration while cells overexpressing 14-3-3ζ did not, suggesting breast cancer metastasis is guided by plithotaxis before but not after epithelial-mesenchymal transition [14] (Figure 3C).

Concluding remarks

We have presented mechanical behaviors and material properties of cells that illustrate physical mechanisms behind both physiological and pathological processes, encouraging researchers to rethink the complex interplay that exists between cell mechanical properties and human health. The ability of cells to fluidize and resolidify in response to mechanical stimulation and collectively migrate by plithotaxis are discoveries that, while exciting, are only in their infancy. Currently there are more questions than answers in the field of cell mechanics. For example, in what other physiological systems would fluidization and resolidification apply? To what extent does plithotaxis hold up in vivo? Finally, the concept of cells being comparable to SGM remains a topic of intense debate as more in-depth studies are needed. As there still exist many unknowns, these newly defined concepts reveal only the tip of the iceberg of the underlying physical phenomena that influence health and disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None

References

- 1.Garanich JS, Mathura RA, Shi ZD, Tarbell JM. Effects of fluid shear stress on adventitial fibroblast migration: implications for flow-mediated mechanisms of arterialization and intimal hyperplasia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6):H3128–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00578.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butcher JT, Penrod AM, Garcia AJ, Nerem RM. Unique morphology and focal adhesion development of valvular endothelial cells in static and fluid flow environments. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(8):1429–34. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130462.50769.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng CM, Steward RL, Jr, LeDuc PR. Probing cell structure by controlling the mechanical environment with cell-substrate interactions. J Biomech. 2009;42(2):187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owan I, Burr DB, Turner CH, Qiu J, Tu Y, Onyia JE, et al. Mechanotransduction in bone: osteoblasts are more responsive to fluid forces than mechanical strain. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(3 Pt 1):C810–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kung C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature. 2005;436(7051):647–54. doi: 10.1038/nature03896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eastwood M, McGrouther DA, Brown RA. Fibroblast responses to mechanical forces. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 1998;212(H):85–92. doi: 10.1243/0954411981533854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu S, Eberhard L, Chen J, Love JC, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, et al. Mechanical anisotropy of adherent cells probed by a three-dimensional magnetic twisting device. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287(5):C1184–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00224.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith PG, Deng L, Fredberg JJ, Maksym GN. Mechanical strain increases cell stiffness through cytoskeletal filament reorganization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285(2):L456–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00329.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward RL, Jr, Cheng CM, Wang DL, Leduc PR. Probing Cell Structure Responses Through a Shear and Stretching Mechanical Stimulation Technique. Cell BIochem Biophys. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puig-De-Morales M, Grabulosa M, Alcaraz J, Mullol J, Maksym GN, Fredberg JJ, et al. Measurement of cell microrheology by magnetic twisting cytometry with frequency domain demodulation. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(3):1152–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellin RM, Kubicek JD, Frigault MJ, Kamien AJ, Steward RL, Jr, Barnes HM, et al. Defining the role of syndecan-4 in mechanotransduction using surface-modification approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(52):22102–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902639106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302(5651):1704–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen M, Wei C, Yamada KM. Cell and fibronectin dynamics during branching morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 16):3376–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tambe DT, Hardin CC, Angelini TE, Rajendran K, Park CY, Serra-Picamal X, et al. Collective cell guidance by cooperative intercellular forces. Nat Mater. 2011;10(6):469–75. doi: 10.1038/nmat3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedl P, Hegerfeldt Y, Tusch M. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis and cancer. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48(5–6):441–9. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041821pf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rorth P. Collective guidance of collective cell migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(12):575–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trepat X, Wasserman MR, Angelini TE, Millet E, Weitz DA, Butler JP, et al. Physical forces during collective migration. Nature Physics. 2009;5:426–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dembo M, Wang YL. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys J. 1999;76(4):2307–16. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler JP, Tolic-Norrelykke IM, Fabry B, Fredberg JJ. Traction fields, moments, and strain energy that cells exert on their surroundings. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282(3):C595–605. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruthamuthu V, Sabass B, Schwarz US, Gardel ML. Cell-ECM traction force modulates endogenous tension at cell-cell contacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):4708–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011123108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sniadecki NJ, Chen CS. Microfabricated silicone elastomeric post arrays for measuring traction forces of adherent cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;83:313–28. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trepat X, Fredberg JJ. Plithotaxis and emergent dynamics in collective cellular migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(11):638–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Tan JL, Cohen DM, Yang MT, Sniadecki NJ, Ruiz SA, et al. Mechanical tugging force regulates the size of cell-cell junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(22):9944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914547107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan R, Klumpers DD, Park CY, Rajendran K, Trepat X, van Bezu J, et al. Substrate stiffening promotes endothelial monolayer disruption through enhanced physical forces. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300(1):C146–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00195.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 1993;260(5111):1124–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7684161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. Cell. 1997;88(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews BD, Overby DR, Mannix R, Ingber DE. Cellular adaptation to mechanical stress: role of integrins, Rho, cytoskeletal tension and mechanosensitive ion channels. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 3):508–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnan R, Park CY, Lin YC, Mead J, Jaspers RT, Trepat X, et al. Reinforcement versus fluidization in cytoskeletal mechanoresponsiveness. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 2007;447(7144):592–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sollich P, Lequeneux F, Hebraud P, Cates ME. Rheology of soft glassy materials. Physiol Rev Lett. 1997;78:2020–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sollich P. Rheological constitutive equation for a model of soft glassy materials. Phys Rev E. 1998;58:738–59. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabry B, Maksym GN, Butler JP, Glogauer M, Navajas D, Taback NA, et al. Time scale and other invariants of integrative mechanical behavior in living cells. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68(4 Pt 1):041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.041914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou EH, Trepat X, Park CY, Lenormand G, Oliver MN, Mijailovich SM, et al. Universal behavior of the osmotically compressed cell and its analogy to the colloidal glass transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(26):10632–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901462106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnan R, Trepat X, Nguyen TT, Lenormand G, Oliver M, Fredberg JJ. Airway smooth muscle and bronchospasm: fluctuating, fluidizing, freezing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;163(1–3):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angelini TE, Hannezo E, Trepat X, Marquez M, Fredberg JJ, Weitz DA. Glass-like dynamics of collective cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):4714–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliver MN, Fabry B, Marinkovic A, Mijailovich SM, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Airway hyperresponsiveness, remodeling, and smooth muscle mass: right answer, wrong reason? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37(3):264–72. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fredberg JJ. Airway smooth muscle in asthma: flirting with disaster. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(6):1252–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12061252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiggs BR, Bosken C, Pare PD, James A, Hogg JC. A model of airway narrowing in asthma and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(6):1251–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tschumperlin DJ. Physical forces and airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2058–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1103121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fredberg JJ. Frozen objects: small airways, big breaths, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(4):615–24. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WL. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1113–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson M. What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? Exp Eye Res. 2006;82(4):545–57. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng D, Juzkiw T, Read AT, Chan DW, Glucksberg MR, Ethier CR, et al. Young’s modulus of elasticity of Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2010;9(1):19–33. doi: 10.1007/s10237-009-0156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou EH, Krishnan R, Stamer WD, Perkumas KM, Rajendran K, Nabhan JF, et al. Mechanical responsiveness of the endothelial cell of Schlemm’s canal: scope, variability and its potential role in controlling aqueous humour outflow. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(71):1144–55. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian B, Kaufman PL. Comparisons of actin filament disruptors and Rho kinase inhibitors as potential antiglaucoma medications. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2012;7(2):177–87. doi: 10.1586/eop.12.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu J, Steeg PS, Price JE, Krishnamurthy S, Mani SA, Reuben J, et al. Breast cancer metastasis: challenges and opportunities. Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):4951–3. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muthuswamy SK, Li D, Lelievre S, Bissell MJ, Brugge JS. ErbB2, but not ErbB1, reinitiates proliferation and induces luminal repopulation in epithelial acini. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(9):785–92. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neal CL, Yao J, Yang W, Zhou X, Nguyen NT, Lu J, et al. 14-3-3zeta overexpression defines high risk for breast cancer recurrence and promotes cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 2009;69(8):3425–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]