Summary

The human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infects helper CD4+ T cells, and causes CD4+ T-cell depletion and immunodeficiency. In the past 30 years, significant progress has been made in antiretroviral therapy, and the disease has become manageable. Nevertheless, an effective vaccine is still nowhere in sight, and a cure or a functional cure awaits discovery. Among possible curative therapies, traditional antiretroviral therapy, mostly targeting viral proteins, has been proven ineffective. It is possible that targeting HIV-dependent host cofactors may offer alternatives, both for preventing HIV transmission and for forestalling disease progression. Recently, the actin cytoskeleton and its regulators in blood CD4+ T cells have emerged as major host cofactors that could be targeted. The novel concept that the cortical actin is a barrier to viral entry and early post-entry migration has led to the nascent model of virus-host interaction at the cortical actin layer. Deciphering the cellular regulatory pathways has manifested exciting prospects for future therapeutics. In this review, we describe the study of HIV interactions with actin cytoskeleton. We also examine potential pharmacological targets that emerge from this interaction. In addition, we briefly discuss several actin pathway-based anti-HIV drugs that are currently in development or testing.

Keywords: HIV-1, actin cytoskeleton, cofilin, LIMK, Arp2/3, CD4+ T cells, macrophages

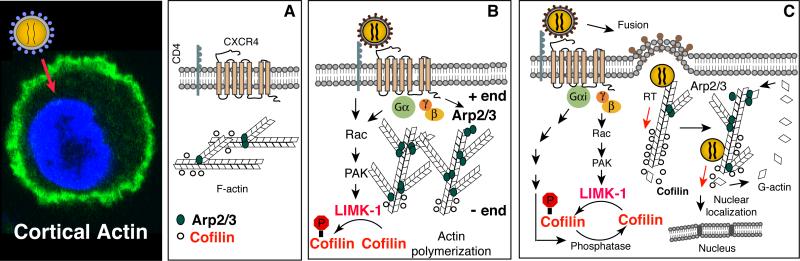

The concept of cortical actin as a barrier for viral intracellular migration

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects cells through binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 to specific receptors, CD4 (1-4), and the coreceptor, CXCR4 (5), or CCR5 (6-11). This interaction leads to fusion of the viral and cellular membranes and entry of the virus. However, in addition to mediating fusion, signal transduction has also been suggested to occur, particularly from gp120 binding to the chemokine coreceptors (12, 13). Nevertheless, subsequent research in transformed cell lines could not appreciate the virological significance of this virus-mediated signaling function (14-20). A renewed attempt was recently made by Yoder and colleagues (21), using HIV infection of primary human blood resting CD4+ T cells as a model. It became immediately evident that HIV-mediated signal transduction from the chemokine coreceptor CXCR4 is an absolute requirement for HIV infection of blood resting CD4+ T cells (21). Further elucidation of the molecular mechanisms has revealed that gp120-mediated chemotactic signaling promotes cortical actin dynamics required for HIV entry and intracellular migration (21-24). From this study (21), Yoder and colleagues have proposed that in the absence of chemotactic signaling or proliferative cytoskeletal remodeling, the cortical actin is relatively static and may present as a barrier for viral intracellular migration (21). To overcome this restriction, HIV uses the chemokine coreceptors to promote chemotactic actin activity for promoting viral entry and early post-entry steps (25) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Model of chemokine signaling and actin dynamics in HIV infection of CD4+ T cells.

Engagement of viral gp120 by the receptor/co-receptor on CD4+ T cells results in activation of the Rac1-PAK-LIMK-Cofilin pathway and actin polymerization which transiently block receptor internalization to facilitate fusion. Following entry of the viral core, the pre-integration complex (PIC) undergoes reverse transcription and nuclear migration possibly in association with actin. Nuclear migration is further facilitated by activation of cofilin and the Rac1-WAVE2-Arp2/3 pathway, which promotes actin treadmilling and pushes the viral PIC to the nucleus.

Perhaps the cortical actin barrier may not be unique to HIV. For intracellular pathogens, the cortical actin cytoskeleton is one of the first intracellular components encountered following entry. This imposing structure, a dense meshwork of cross-linked filamentous actin (F-actin), presents a barrier that must be modified or bypassed to access the intracellular compartments. Some viruses may take advantage of the endocytic entry pathway to avoid the cortical actin; however, for pathogens like HIV, which enter the cell at the plasma membrane, this barrier must be engaged.

Model of HIV hijacking the chemokine signaling pathway to engage the actin cytoskeleton

The actin cytoskeleton, if effectively subverted by a pathogen, can be an important host cofactor, producing essential driving forces and scaffolds for pathogenic processes such as intracellular migration, nucleic acid synthesis and transcription, or virion assembly and budding. Many viral pathogens have evolved the capacity to directly modify the actin cytoskeleton through pathogen-encoded actin-modulating proteins. This is particularly true of vaccinia virus and baculovirus, which recruit and activate the actin branching and nucleation factor Arp2/3 to promote intracellular motility and dissemination (26-30). In the case of vaccinia virus, the virally encoded A36R protein, which localizes to the envelope of intracellular enveloped virus (IEV), recruits the Arp2/3-activator N-WASP (27) to trigger actin polymerization. Similarly, baculovirus directly activates Arp2/3 through the pathogen-encoded protein P78/83, which mimics N-WASP-mediated Arp2/3 activation (28, 29). This process facilitates viral assembly and release. Recently, αherpesvirus has also been shown to directly phosphorylate an upstream regulator of the actin-depolymerizing factor cofilin to mediate efficient spread (31). This is achieved by the virally expressed US3 kinase protein by phosphorylation of an upstream regulator, the group I PAK kinases (31). In addition, it has also been reported that poliovirus utilizes an actin-dependent mode of intracellular motility through an as yet unknown mechanism (32). In contrast to the above-mentioned pathogens (excluding poliovirus), HIV-1 possesses a comparatively small genome of 9 genes and does not appear to encode a viral protein with dedicated actin-modulating functions. However, current research has demonstrated a heavy dependence on the actin cytoskeleton for viral infection. Indeed, the virus has also evolved a great capacity to engage the actin cytoskeleton by exploiting the chemotactic signaling network, through selective engagement of the chemokine coreceptors during entry.

In the past five years, detailed molecular characterization of this early interaction has led to the formation of a nascent model of how HIV hijacks cell signaling for actin dynamics in the infection of blood CD4+ T cells (21-24, 33-39). As illustrated by Spear and colleagues (36) (Fig. 1), HIV binding to CD4/CXCR4 triggers transient actin polymerization through the activation of Rac1-PAK1/2-LIMK-cofilin (22) and WAVE2-Arp2/3 (34). It is evident that HIV signaling may impinge upon actin filaments from both the barbed and pointed ends: the pointed end is depolymerized as a result of dynamic signaling to LIMK and cofilin (21, 22), whereas at the barbed end, actin polymerization is nucleated by Arp2/3, which is activated by the upstream regulator WAVE2 a nucleation-promoting factor (NPF) (34). Both LIMK-cofilin and WAVE2-Arp2/3 signaling occur in HIV infection of primary blood CD4+ T cells and macrophages (21, 22, 34). HIV-mediated actin signals also appear to redundantly use multiple pathways, both the Gαi-dependent and -independent, to ensure proper activation of actin dynamics.

Although much of the detail by which HIV-1 utilizes actin cytoskeleton remains to be elucidated, the specific involvement of actin dynamics in viral early steps has been amply demonstrated (reviewed in 36). Mechanistically, HIV-mediated early actin polymerization may transiently block the internalization of CXCR4, stabilizing the fusion complex for viral entry (22). Actin dynamics may also be involved in the uncoating process (36) and other early post-entry steps. The viral pre-integration complex (PIC) may be directly anchored onto F-actin for reverse transcription (21, 40). In addition, HIV-mediated cofilin and Arp2/3 activity increases cortical actin treadmilling, promoting the migration of PIC towards the nucleus of the cell (21, 34).

Experimental results have suggested a trinity of the cortical actin in promoting viral early steps, including entry, reverse transcription, and nuclear migration. For example, the actin inhibitor jasplakinolide specifically inhibits viral DNA synthesis and nuclear migration in resting CD4+ T cells (21, 41). Similarly, knockdown of LIMK1 in T cells decreases cortical actin density and actin dynamics, which lead to an inhibition of viral entry, DNA synthesis, and nuclear migration (22). On the other hand, knockdown of cofilin leads to accumulation of filamentous actin, which enhances viral early DNA synthesis but inhibits viral nuclear migration (21). The cofilin knockdown phenotype strikingly resembles the Arp2/3 knockdown phenotype recently observed by Spear et al. (34), in which viral DNA synthesis is enhanced but viral nuclear migration is inhibited. It appears that longer retention of viral core in the cortical actin layer stimulates viral reverse transcription but concomitantly hinders viral nuclear migration. Interestingly, although the knockdown of these actin modulators all affect actin dynamics, significant differences exist in cellular responses. For instance, a high degree of cofilin knockdown is lethal in T cells, but the knockdown of LIMK1 or Arp2/3 (80-90%) is well-tolerated (21, 22, 34).

The elucidation of the role of actin cytoskeleton has also started to shed light on how HIV may interact with various blood CD4+ T-cell subtypes differentially. For example, the CD45RO memory CD4+ T cells have been identified as a major HIV reservoir (42, 43). In patients, memory CD4+ T cells harbor more integrated proviral DNA than CD45RA naive T cells (42-45). In cell culture conditions, CD45RO memory T cells indeed support higher levels of HIV-1 replication than CD45RA T cells (42, 45-48). Recently, Wang and colleagues (24) have demonstrated that there are marked differences both in cytoskeletal structure and in chemotactic actin dynamics between memory and naive T cells. Memory CD4+ T cells possess a higher cortical actin density and can be distinguished as CD45RO+Actinhigh. In contrast, naive T cells are phenotypically CD45RA+Actinlow. In addition, the cortical actin in memory CD4+ T cells is more dynamic and can respond to low dosages of chemotactic induction (by SDF-1), whereas that of naive cells cannot, despite a similar level of the chemokine receptor (CXCR4) present on both cells. These differential actin phenotypes likely result from a previous antigenic response that leaves a permanent imprint on memory T cells. It is possible that in memory T cells, the actin cytoskeleton and its regulatory pathways are profoundly remodeled to predispose them to faster and greater responses in the event of antigenic re-exposure. This higher cortical actin activity in memory T cells, unfortunately, also predisposes them to HIV-1 infection; it was found that memory but not naive T cells are highly responsive to HIV-mediated actin dynamics, which mimic the chemotactic process to facilitate viral entry and DNA synthesis (24).

The study of HIV interactions with actin cytoskeleton at the fundamental molecular level has facilitated the understanding of viral pathogenesis, as exemplified above. As this interaction is also critically important for HIV-1 infection of primary blood CD4+ T cells, it presents multiple novel targets for anti-HIV-1 pharmaceuticals.

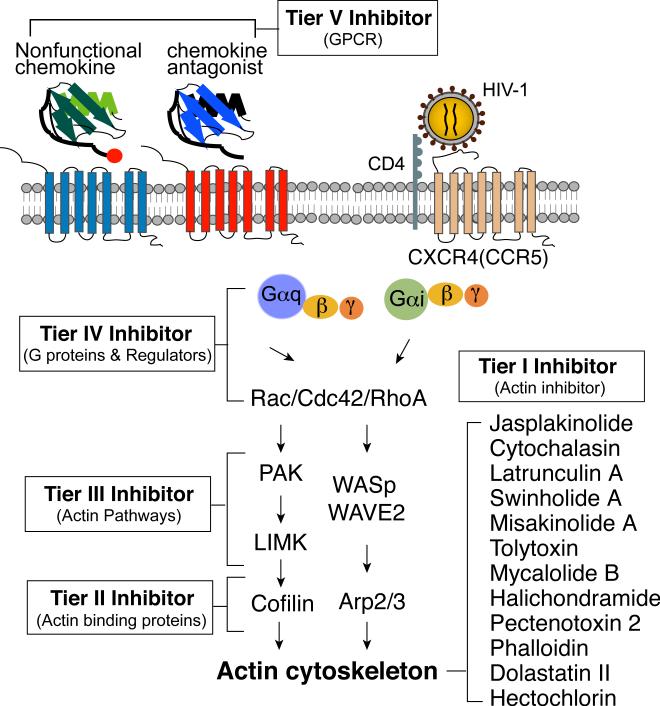

Novel anti-HIV therapeutics targeting HIV-mediated chemotactic signaling and actin dynamics

From the model presented in Fig. 1, there are at least five tiers of targets that are related to actin and its regulatory pathways (Fig. 2). The first tier is actin itself, meaning those drugs that can directly interact with actin and block viral interaction with actin cytoskeleton. Additionally, actin inhibitors may also prevent HIV-mediated actin dynamics through inhibiting actin polymerization or depolymerization. The second tier targets are the direct actin regulators, which endogenously control actin dynamics for cell maintenance, migration, adhesion, and cytokinesis. The third tier targets are the upstream regulators of the second tier targets. This includes upstream kinases and phosphatases. The fourth tier targets are the heterotrimeric G proteins, monomeric GTPases, and their regulators that directly transduce receptor signals to actin dynamics. The fifth tier targets are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as the chemokine receptors. Each of these tiers represents unique pharmacological and biological targets that play widely varying roles in normal cellular function and viral infection. As a result, there are widely divergent cytological and virological effects when targeting a particular molecule. Given this, each tier will be considered and analyzed for its likelihood for pharmaceutical intervention.

Fig. 2. Novel anti-HIV therapeutic targets of the actin signaling pathway.

Exhibited are the five tiers of novel anti-HIV pharmacological targets in the chemokine/actin signaling pathway. The two major pathways known to be activated by HIV-1, the Rac1-PAK-LIMK-Cofilin pathway, and the Rac1-WAVE2-Arp2/3 pathway, are also illustrated.

The first tier targets: monomeric and filamentous actin

The first tier of pharmacological targets is actin itself: those drugs that directly interact with actin, either monomeric or filamentous actin. The sponge toxin jasplakinolide binds to and stabilizes filamentous actin (49), whereas other drugs such as latrunculin A binds to G-actin (50). There are many available small molecules that can exert various effects on actin dynamics such as crosslinking, capping, sequestering, or severing. These drugs may include the following: the F-actin-stabilizing phallotoxins (e.g. phalloidin); the polymerization-promoting marine sponge toxin jasplakinolide; the barbed-end capping fungal toxins, the cytochalasins; the G-actin sequestering sponge toxins, the latrunculin family; and, among many others, the F-actin severing marine sponge toxin swinholide. Collectively, these toxins mechanistically mimic most of the host regulatory mechanism of modulating the actin cytoskeleton. As a result, these toxins can be used to directly probe actin cytoskeletal processes and how they contribute to HIV-1 infection. For example, two of these actin inhibitors, jasplakinolide (Jas) and latrunculin A (Lat-A), have been extensively used to probe their virological effects (21, 23, 24). Yoder et al. (21) have shown that at higher dosages (3 μM), Jas inhibited LFA-1 activation and T-cell activation even with transient treatment (3 h), whereas at low dosage (120 nM and below), such treatment did not inhibit T-cell activation but inhibited HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells. Jas blocked viral reverse transcription and nuclear migration. Conversely, transient (5 min) and low dosage (25 nM) treatment of resting CD4+ T cells with Lat-A enhanced viral infection of resting CD4+ T cells, likely by inducing low-level actin depolymerization and subsequent polymerization. However, higher dosages of Lat-A (2.5 μM) inhibited HIV infection (21, 24). These results suggest that over-depolymerization or irreversible stabilization of actin inhibits HIV replication, whereas slight and transient depolymerization of actin may increase actin dynamics and enhances viral replication. These data are consistent with the model that the cortical actin exists primarily as a barrier to HIV infection and needs to be dynamically rearranged during infection. The effects of cytochalasins were similarly tested by Bukrinskaya et al. (40) in transformed cell lines. Pretreatment with 5 μM cytochalasin D was found to reduce late-phase viral DNA synthesis, suggesting that filamentous actin may be involved in viral reverse transcription. Although currently known actin inhibitors, including those described above, are critical research tools, they are unlikely to be developed as anti-HIV-1 pharmaceuticals. This is largely because their therapeutic index, a ratio of the LD50 (median lethal dose) to the ED50 (half maximal effective dose), is normally low—less than 10 in most instances. None of these actin inhibitors have been used in clinical treatment of other human diseases such as cancers.

Mechanistically, the inhibition of HIV infection by these actin-interacting small molecules is still not well understood. It is likely that they may act directly by blocking HIV attachment to actin cytoskeleton or by inhibition of HIV-mediated actin dynamics. It has been known that multiple virion proteins, such as the large subunit of the reverse transcriptase (51), the nucleocapsid (52-54), and Nef (55), can interact with actin, although the exact interacting domains remain unknown. Future mapping of these domains would offer novel insights into whether this interface can be targeted by small molecule inhibitors.

The second tier targets: actin-binding proteins

The second tier targets are those proteins that directly modulate the actin cytoskeleton as part of the normal host actin regulatory apparatus. These targets include the following: the actin-depolymerizing factors, such as cofilin, twinfilin, and gelsolin; the actin branching and nucleation factor Arp2/3; the actin-polymerization-promoting formins; the actin-capping proteins, such as CapZ and tropomodulin, which promote depolymerization through barbed-end capping, and polymerization through pointed-end capping, respectively; thymosin β4, which sequesters free G-actin; profilin, which binds G-actin and facilitates polymerization through ADP-ATP exchange in associated actin monomers; the anti-capping proteins of the ENA/VASP family; the actin cross-linking proteins, such as spectrin and filamin A; the ERM family proteins ezin, radixin, and moesin that cross-link plasma membrane and actin cytoskeleton. Of these, only cofilin, Arp2/3, filamin A, moesin, and recently gelsolin have been studied in relation to HIV-1 infection (21, 22, 34, 56-59). In addition, studies into the role of VASP in HIV-1 infection are currently being conducted in our laboratory (60). As with the studies targeting the first tier, the cytological and virological effects of targeting second tier molecules will be explored using cofilin and Arp2/3 as examples.

Yoder and colleagues (21) have studied the role of cofilin-mediated actin dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Specifically, they used a cofilin-activating peptide, S3, and shRNA knockdown of cofilin to investigate role of cofilin in HIV-1 infection of blood resting CD4+ T cells (21). The S3 peptide is based on the N-terminal sequence of cofilin and contains serine 3, which can be competitively phosphorylated in lieu of cofilin (21). This has the net effect of increasing cofilin activation by increasing dephosphorylated cofilin. Treatment of resting CD4+ T cells with S3, prior to HIV-1 infection, led to a marked enhancement of HIV-1 replication of resting T cells (21), likely resulting from increases in actin dynamics in response to cofilin activation. Consistently, low level shRNA knockdown (10-30%) of cofilin in primary CD4+ T cells led to the accumulation of the cortical actin that enhanced viral DNA synthesis but inhibited viral nuclear migration and viral replication (21). Notably, high level or persistent inhibition of cofilin is lethal in T cells (21), as such, small-molecule inhibitors of cofilin are unlikely to have any therapeutic value.

Arp2/3 was also extensively investigated recently by Spear et al. (34) in regards to HIV-1 replication. Arp2/3 is a heptameric complex that binds to the side of an actin filament and induces the nucleation of an F-actin branch. This process is dynamically regulated NPFs (such as WAVE2 and WASp) and cortactin-like proteins. This process is required for force generation during endocytosis and chemotaxis, among many other processes. In HIV infection, shRNA knockdown of Arp3 resulted in a dramatic inhibition of HIV-1 replication (34, 61). Spear et al. further elucidated that Arp3 knockdown resulted in higher viral DNA synthesis and lower nuclear migration (34), suggesting that decreasing actin branching inhibits viral nuclear migration but enhances viral DNA synthesis. The increase in viral DNA synthesis is likely stimulated by longer retention of the viral preintegration complex in the cortical actin layer. In addition, a small-molecule inhibitor of Arp2/3, CK548 (62), also drastically inhibited HIV-1 nuclear migration and infection of CD4+ T cells at dosages that did not inhibit T-cell activation (34). The Arp3 shRNA knockdown phenotypes resemble many of those in the cofilin knockdown. However, unlike the lethal phenotype of cofilin knockdown, knockdown of Arp2/3 is well tolerated by T cells. The Arp2/3 knockdown (80-90%) cell lines have been stably grown in our laboratory for several years (34).

The second tier targets may represent a more viable field of candidates for drug discovery and development than the first tier biological agents. Furthermore, some of these proteins (e.g. formins and filamin-A) serve specialized roles in the cells, and some even display tissue-specific expression patterns, which reduce the chances of off-target cytopathological effects. Notably, very few drugs targeting this tier have been developed, with some exceptions, including Arp2/3 (62) and formins (63). However, many of these targets are embryonic lethal in mouse gene knockout studies, including cofilin (64), profilin (65), and Arp2/3 (66). As such, persistent pharmaceutical inhibition of second tier factors may have substantial cytopathic consequences. The third, fourth, and fifth tier-directed pharmaceuticals may be more practical for the development of novel anti-HIV drugs.

The third tier targets: direct regulators of actin pathways

The third tier targets in the actin regulatory pathways consist of upstream regulators of the actin-modulating proteins. These include the cofilin kinase LIMK1/2 and TESK, and the cofilin phosphatases, PP1α and slingshot, the Arp2/3-regulating NPFs, including the WASp/WAVE family, and cortactin, and many kinases and phosphatases that collectively regulate actin pathways.

LIMK1/2 phosphorylates cofilin on serine 3, resulting in deactivation of the actin-severing activity. LIMK is specifically activated by phosphorylation in its activation loop by upstream PAK1 (67), PAK4 (68), and ROCK (69). Detailed studies on the role of LIMK1 in HIV-1 infection were performed by Vorster et al.(22). LIMK1 was specifically activated both in blood resting CD4+ T cells and in macrophages after exposure to HIV-1 (22), indicating a viral functional conservation for LIMK activation (22). This LIMK activation was shown to be dependent on Gαi-dependent signaling; although, early LIMK phosphorylation appeared to be Gαi-independent (22). Vorster et al. (22) further mapped the HIV-mediated signaling pathway to be the Rac1-PAK1/2-LIMK-cofilin pathway. To more specifically address the role of LIMK1, an shRNA knockdown was performed. LIMK1 can be effectively knocked down (80-90%) in CD4+ T cells, and the cell lines carrying stable LIMK1 knockdown have also been grown in our laboratory for several years (22). These cells have a decreased F-actin content and actin polarization and are relatively resistant to HIV infection (22, 35). The decrease in cortical actin density also leads to an increase in CXCR4 internalization and surface recycling. Thus, LIMK-mediated early actin polymerization may result in a temporary block to CXCR4 internalization, facilitating viral fusion and CXCR4 signaling. The LIMK1 knockdown cells also limit high-level viral entry, and reduce viral DNA synthesis and nuclear migration (22). In addition to shRNA knockdown of LIMK1, transient treatment of resting CD4+ T cells with okadaic acid, a PP1 and PP2A inhibitor, was shown to promote LIMK1 hyperphosphorylation in the activation loop. This transient LIMK1 activation led to a transient actin polymerization that dramatically enhanced HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells (22). The enhancement was attributed to increases in viral DNA synthesis and nuclear migration (22).

Cofilin and the Arp2/3 complex work together to regulate actin treadmilling (70). Previously, Komano et al. (61) have suggested that Arp2/3 may be involved in lentiviral infection. Recently, Spear et al. (34) have found that HIV-1 infection of resting CD4+ T cells and macrophages triggers WAVE2 phosphorylation. WAVE2 has been shown to act as a coincidence detector for Rac activation, acidic phospholipids (particularly PIP3), and certain WAVE2 serine/threonine kinases, which are all required for complete activation of the WAVE regulatory complex (WRC) (71-73). In the absence of chemotactic stimulation or T-cell activation, the WAVE2 WRC exists in an autoinhibited conformation in which the Arp2/3-activating domain, known as the VCA, is sterically occluded (71, 73-76). With recent data from Spear et al. (34) and others (61, 77), there is sufficient evidence to indicate specific WAVE2 activation in response to HIV-1 infection, indicating that it is a relevant target for novel therapeutics. Much like the WAVE2 WRC, WASp dynamically regulates the Arp2/3 complex via a VCA domain and exists in an autoinhibited state absent upstream activating signals (71). In the autoinhibited state, WASp's VCA domain is bound to the GTPase-binding domain (GBD), preventing Arp2/3 activation (71). Engagement of cdc42 by the WASp GBD and PIP2 acts to prime WASp for Arp2/3 activation, driving actin polymerization (78-81). Currently, the only inhibitors of NPFs are the N-WASP inhibitors, a cyclic peptide, 187-1 (82), and the small molecule inhibitor wikostatin (83). These agents have not been characterized in regards to HIV-1 inhibition. However, the Arp2/3 inhibitor CK-548 has been shown to dramatically inhibit HIV-1 infection (34), suggesting that upstream NPFs are viable targets for novel anti-HIV therapeutics. Nevertheless, targeting NPFs sch as WASp may cause immunodeficiency. The WASp gene is naturally deleted in patients with Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, which was originally characterized clinically (84) as an X-linked disorder in patients presenting thrombocytopenia, bloody diarrhea, eczema, and recurrent ear infections. In 1994, Derry et al. (85) identified WASp, the Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein, as the gene mutated in WAS patients. Subsequently, two other, related disorders have been linked to WASp mutation, including X-linked thrombocytopenia (XLT) (86) and X-Linked severe congenital neutropenia (XLN) (87). Mutation of WASp, in addition to the aforementioned clinical manifestations, is associated with combined immunodeficiency, including cytolytic, antigen presenting, and phagocytic defects (88-92). Given the severity of symptoms associated with WASp mutation, targeting WASp is unlikely to yield useful pharmaceuticals. However, this does not exclude possibilities of targeting other WASp/WAVE family proteins or their upstream regulators.

LIMK1, along with 24 other genes, are haplodeleted in people with Williams syndrome (WS) (93). WS or Williams-Beuren syndrome was first described by Williams et al. (94) and Beuren et al. (95) as common features exhibited by patients with supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS). The patients exhibited mild mental retardation, ‘elfin’ facial features (broad forehead, full lips, eyes set wide apart, etc.), and cardiovascular problems, including the life-threatening SVAS (94-96). Thirty-two years after its discovery, WS was linked to a heterozygous deletion in the elastin gene (ELN) in the chromosome region 7q11.23 (97). Later, the WS hemideletion was shown to include approximately 25 genes in the 1.6 MB heterozygous deleted region, including the cofilin kinase LIMK1 (98, 99). The deletion of ELN has been explicitly linked to most of the cardiovascular defects, particularly SVAS (100, 101). The neurodevelopmental genotype-phenotype correlation is still uncertain: however, it is likely related to the hemizygosity of WBSCR11, CYLN2, GTF2I, NCF1, and perhaps LIMK1 (93). LIMK1 knockout, as opposed to hemideletion in WS, in mouse models has been linked to alterations of hippocampal spine morphological and spatial learning (102). Nevertheless, children with WS do not have the severe multiple developmental disorders normally seen in other developmental genetic diseases. Together, these findings suggest that limited inhibition of LIMK1 is not fatal or likely to cause serious side effects in adults. Thus, LIMK inhibitors are in development for treating various human diseases such as metastatic cancer (103-107), Alzheimer's disease, and drug addiction (108). Recently, we have screened and tested a group of novel LIMK inhibitors for their anti-HIV activity (109) and identified several lead compounds with high specificity for LIMK. These compounds demonstrated dosage-dependent inhibition of HIV with minimal cytotoxicity and a therapeutic index greater than 10.

The third tier targets, which are considerably more diverse than their first and second tier counterparts, are far more promising for the development of HIV-1 pharmaceuticals. Unlike their second tier counterparts, many of these genes are not embryonic lethal in mouse gene knockout studies. Among them, LIMK1 is the most studied (22, 35, 109) and a valuable target. In addition to the unique properties of LIMK1, third tier targets often exhibit an even higher degree of tissue-specific expression and context-dependent function than the second tier proteins. As such, proteins of this tier are truly viable candidates for pharmacological intervention in HIV-1 infection.

The fourth tier targets: the G proteins

The fourth tier molecular targets are the upper level signaling molecules that transduce receptor signaling to actin cytoskeleton. Proteins in this category include the following: the heterotrimeric G proteins; the heterotrimeric G proteins regulators, largely the Regulator of G protein signaling (RGSs) proteins; the monomeric G proteins (particularly the Rho-family GTPases); the monomeric G protein regulating guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs). Given the enormous scope of these families of proteins, only a few from which HIV-specific literature has emerged are discussed.

Yoder and colleagues (21) showed that uncoupling of Gαi from the chemokine coreceptor with pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment inhibits HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells. HIV-mediated activation of cofilin, LIMK1, and WAVE2 in resting CD4+ T cells has also been shown to be dependent on PTX-sensitive Gαi and –insensitive Gαq subunits (21, 22, 34). Vorster et al. (22) further exhibited HIV-1-mediated activation of Rac1 and PAK1/2 in resting CD4+ T cells in response to treatment with HIV-1. However, the other representative Rho-family GTPase members, cdc42 and RhoA, were not activated in resting CD4+ T cells (22). Furthermore, a Rac1 and PAK1-dependent macropinocytic route may be partially responsible for HIV-1 entry into macrophages (110). As such, Rac1 and GEFs are promising targets for pharmacological intervention. There are 23 Rho-family GTPases and a myriad of GEFs in the mammalian genome, and few have been extensively characterized, with the exception of the canonical representatives of the three major Rho-family GTPases, RhoA, Rac1, and cdc42 (111). Many of these proteins display tissue-specific expression patterns and unique functions, and should be investigated for potential roles in HIV-1 infection.

The fifth tier targets: G protein-coupled receptors

The chemokine receptors directly regulate actin dynamics through binding to chemokine and initiation of chemotactic signaling. Currently there are approximately 50 chemokines and 20 receptors identified. Among them include the two main chemokine co-receptors of HIV-1, CXCR4 and CCR5. The chemokine network regulates leukocyte migration in immunity and inflammation and is implicated in the pathogenesis of many diseases including HIV-1 infection (39, 112). As HIV-1 utilizes CCR5 and CXCR4 for entry, it is well documented that their natural ligands, SDF-1, RANTES, and MIP-1α/β (6), can act as potent antagonists of HIV-1 binding and entry (113, 114). Additionally, numerous antagonists to the viral coreceptors have been developed, with clinical approval for maraviroc (115). In regards to CXCR4 antagonists, such as AMD3100, clinical trials were discontinued when side effects and low anti-HIV-1 efficacy manifested (116). AMD3100 is currently approved for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization for limited uses. As such, targeting CXCR4 directly may be problematic.

It has become increasingly evident that the signaling function of chemokine receptors, not only CXCR4/CCR5 but also others, can impact HIV infection (37). The serum levels of the CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 have been shown to positively correlate with viral loads in infected patients (117). Furthermore, CCL19 was additionally correlated with mortality in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients (118). Indeed, in an in vitro model of HIV-1 latent infection, CCL19 treatment of resting CD4+ T cells prior to infection greatly enhances viral latent infection (119). This effect was due largely to an increase in the efficiency of viral nuclear migration (41). Furthermore, these effects were linked to CCL19-mediated cofilin activation and changes in the actin cytoskeleton, as jasplakinolide treatment blocked the CCL19-mediated enhancement of viral replication (41). Other chemokines such as CCL2 have also been shown to enhance HIV-mediated actin polymerization, greatly facilitating HIV entry and DNA synthesis (120). CCL2 recruits memory T cells to sites of tissue injury, infection, and inflammation (121), and there is a strong positive correlation between HIV viremia and CCL2, both at the mRNA level and at the level of serum concentration (122).

Given the effects of chemokines on HIV infection and disease progression, targeting GPCR could potentially inhibit both HIV infection and virus-mediated pathogenesis. Therapeutically, GPCR signaling can be targeted by using inhibitory antibodies, small-molecule antagonists, nonfunctional chemokines that bind but do not activate viral-dependent pathways, or chemokine antagonists that bind and transduce inhibitory signals for HIV replication. In addition, for many chemokines, extension or truncation of the N-terminus abrogates their signaling activity while preserving their binding properties. This method has generated antagonists such as Met-RANTES, APO-RANTES, and PSC-RANTES for treating HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus infection (123-125). There are a number of small molecules and chemokine antagonists that are in development for the treatment of an array of diseases such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, and allergic inflammation. Most of these agents are available, either commercially or through material transfer agreement. Nevertheless, these available resources have not been systematically used and tested for the treatment of HIV-1 infection Other chemotactic receptors of non-GPCR category are also potential targets for therapeutic intervention. For instance, it was shown recently that slit2, a chemotactic factor involved in neuronal axon guidance, binding to its receptor Robo1 exerts effects on HIV-1 infection (126, 127). In particular, the N-terminal domain of slit2 was found to reduce HIV-1 infection through binding to Robo1, which abrogated HIV-1 envelope-induced actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Slit2N specifically attenuated the HIV-1 envelope-induced Rac1-LIMK-cofilin signaling pathway (127). Slit2N has also been shown to prevent HIV viral gp120-induced hyperpermeability in lymphatic endothelia, which is a contributing factor to HIV-1 dissemination in the host (128). This was mediated by slit2N binding to Robo4 on endothelial cells (128). As such, a Robo agonist could perhaps reduce both entry of the virus and its subsequent dissemination within the lymphatic system.

Drugs targeting multiple HIV-dependent signaling molecules

In addition to targeting known HIV-dependent signaling molecules, there are also general kinase or phosphatase inhibitors that can inhibit HIV infection through interference with HIV-mediated signaling pathways. For instance, a general tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein, in particular, has been shown to inhibit HIV infection of blood resting CD4+ T cells and macrophages (129-131). Genistein is a phytoestrogen found in a number of plants such as soybeans and flemingia vestita (132) and is being tested for treatment of cancers, such as leukemia (133, 134) and prostate cancer (135, 136). Genistein also inhibits SDF-1-mediated chemotaxis of CD4+ T cells (137) and can modulate the cellular distribution of actin-binding proteins formin-2 and profilin (138). In a recently study by Guo et al. (130), genistein was found to decrease the overall phosphorylation of LIMK and cofilin, two of the main actin regulators involved in HIV infection (21, 22). In cells, multiple actin regulatory proteins, such as gelsolin (139, 140), villin (141), ezrin (142), cortactin (143-145), Rac1 (146), and WASp (147), require tyrosine phosphorylation for activity. It is possible that genistein may additionally affect these actin regulators, leading to the inhibition of HIV-1 infection of blood CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, a recent study also found that genistein treatment abrogated a PKA-RhoA-dependent signaling cascade in endothelial cells through an unknown mechanism (148).

Genistein consumption in Southeast Asians is associated with a lower incidence of metastatic prostate cancer (135, 149-152). The average blood levels of genistein in Japanese men, who subsist on a soy-based diet, were approximately 0.28 μM (151). In a phase I human clinical trial, subjects sustained a maximal total plasma genistein concentration between 4.3 to 16.3 μM, with a drug half-life of 15 to 22 h, and no significant cytotoxicities were observed (136). Of note, these concentrations have been shown to be capable of inhibiting HIV infection of blood resting CD4+ T cells in vitro (130).

Given that HIV infection is a chronic disease that requires life-long treatment, naturally occuring, low cytotoxic compounds such as genistein may offer great therapeutic value for the long-term management of HIV disease. These inhibitors may interfere with virus-mediated actin activity while minimally affecting cellular actin dynamics. Such inhibitors may not drastically diminish HIV replication in a short term, but with long-term treatment and possibly lower viral drug-resistance, persistent depression of viral loads could be achievable.

Conclusion

The development of novel anti-HIV pharmaceuticals is of paramount importance for the abrogation of the HIV pandemic. In this review, we explored the actin signaling pathways that are of critical import for viral infection, particularly for the process of entry, reverse transcription, and nuclear migration. We reviewed and evaluated different tiers of potential targets along the HIV-mediated chemotactic signaling cascades. It is clear that targeting these processes hold realistic prospects for novel pharmaceutical interventions. It would not be a surprise that if in the coming years, some of these drugs may be applied for clinical management of HIV infection. Though not extensively addressed in this review, the actin signaling pathways discussed herein are not merely vehicles for propelling viral processes but are critical to viral pathogenesis as well. It is likely that these novel pharmaceuticals, though targeting host proteins, may influence the course of viral pathogenesis in chronically infected patients. As a result, these novel pharmaceuticals may help to reduce morbidity and mortality. In addition, drugs targeting cellular proteins normally exhibit a lower propensity for viral resistance, as most virus-host interactions are highly conserved.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this paper to Bret Granato who was tragically lost to AIDS in 1995. In the past five years, research in the Wu laboratory was funded in part by the generous donations of Tracy Daugherty and the other donors and riders of the NYCDC AIDS Rides organized by M. Rosen, and by Public Health Service grant 1R01AI081568 and 1R03AI093157 from NIAID to YW. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a research loan from the George Mason University College of Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Dalgleish AG, Beverley PC, Clapham PR, Crawford DH, Greaves MF, Weiss RA. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDougal JS, et al. Cellular tropism of the human retrovirus HTLV-III/LAV. I. Role of T cell activation and expression of the T4 antigen. J Immunol. 1985;135:3151–3162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDougal JS, Kennedy MS, Sligh JM, Cort SP, Mawle A, Nicholson JK. Binding of HTLV-III/LAV to T4+ T cells by a complex of the 110K viral protein and the T4 molecule. Science. 1986;231:382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.3001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maddon PJ, Dalgleish AG, McDougal JS, Clapham PR, Weiss RA, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkhatib G, et al. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe H, et al. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng H, et al. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doranz BJ, et al. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dragic T, et al. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CCCKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis CB, et al. Signal transduction due to HIV-1 envelope interactions with chemokine receptors CXCR4 or CCR5. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1793–1798. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman D, et al. Macrophage-tropic HIV and SIV envelope proteins induce a signal through the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Nature. 1997;389:981–985. doi: 10.1038/40173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo RC, Lusso P. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farzan M, et al. HIV-1 entry and macrophage inflammatory protein-1beta-mediated signaling are independent functions of the chemokine receptor CCR5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6854–6857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aramori I, Ferguson SS, Bieniasz PD, Zhang J, Cullen B, Cullen MG. Molecular mechanism of desensitization of the chemokine receptor CCR-5: receptor signaling and internalization are dissociable from its role as an HIV-1 co-receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:4606–4616. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhatib G, Locati M, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. HIV-1 coreceptor activity of CCR5 and its inhibition by chemokines: independence from G protein signaling and importance of coreceptor downmodulation. Virology. 1997;234:340–348. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosling J, et al. Molecular uncoupling of C-C chemokine receptor 5-induced chemotaxis and signal transduction from HIV-1 coreceptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5061–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doranz BJ, et al. Identification of CXCR4 domains that support coreceptor and chemokine receptor functions. J Virol. 1999;73:2752–2761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2752-2761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brelot A, Heveker N, Montes M, Alizon M. Identification of residues of CXCR4 critical for human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor and chemokine receptor activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23736–23744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoder A, et al. HIV envelope-CXCR4 signaling activates cofilin to overcome cortical actin restriction in resting CD4 T cells. Cell. 2008;134:782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vorster PJ, et al. LIM kinase 1 modulates cortical actin and CXCR4 cycling and is activated by HIV-1 to initiate viral infection. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12554–12564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.182238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo J, Wang W, Yu D, Wu Y. Spinoculation triggers dynamic actin and cofilin activity facilitating HIV-1 infection of transformed and resting CD4 T cells. J Virol. 2011;85:9824–9833. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05170-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Guo J, Yu D, Vorster PJ, Chen W, Wu Y. A dichotomy in cortical actin and chemotactic actin activity between human memory and naive T cells contributes to their differential susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35455–35469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo J, Xu X, Yuan W, Jin T, Wu Y. HIV gp120 is an aberrant chemoattractant for blood resting CD4 T cells. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10:636–642. doi: 10.2174/157016212803901365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frischknecht F, Cudmore S, Moreau V, Reckmann I, Rottger S, Way M. Tyrosine phosphorylation is required for actin-based motility of vaccinia but not Listeria or Shigella. Curr Biol. 1999;9:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frischknecht F, et al. Actin-based motility of vaccinia virus mimics receptor tyrosine kinase signalling. Nature. 1999;401:926–929. doi: 10.1038/44860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohkawa T, Volkman LE, Welch MD. Actin-based motility drives baculovirus transit to the nucleus and cell surface. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:187–195. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goley ED, et al. Dynamic nuclear actin assembly by Arp2/3 complex and a baculovirus WASP-like protein. Science. 2006;314:464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1133348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boujemaa-Paterski R, et al. Listeria protein ActA mimics WASp family proteins: it activates filament barbed end branching by Arp2/3 complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11390–11404. doi: 10.1021/bi010486b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob T, Van den Broeke C, Van Troys M, Waterschoot D, Ampe C, Favoreel HW. Alphaherpesviral US3 kinase induces cofilin dephosphorylation to reorganize the actin cytoskeleton. J Virol. 2013;87:4121–4126. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03107-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaughan JC, Brandenburg B, Hogle JM, Zhuang X. Rapid actin-dependent viral motility in live cells. Biophys J. 2009;97:1647–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu D, Wang W, Yoder A, Spear M, Wu Y. The HIV envelope but not VSV glycoprotein is capable of mediating HIV latent infection of resting CD4 T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spear M, Guo J, Turner A, Weifeng W, Yu D, Wu Y. Arp2/3-dependent nuclear migration in HIV-1 infection of CD4 T cells.. The 2012 Retroviruses meeting.; Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, Guo J, Wu Y. Involvement of LIM Kinase 1 in actin polarization in human CD4 T cells. Commun Integr Biol. 2012 Jul-Aug;:5. doi: 10.4161/cib.20165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spear M, Guo J, Wu Y. The trinity of the cortical actin in the initiation of HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology. 2012;9:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y. Chemokine control of HIV-1 infection: beyond a binding competition. Retrovirology. 2010;7:86. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y, Yoder A. Chemokine coreceptor signaling in HIV-1 infection and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000520. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y. The co-receptor signaling model of HIV-1 pathogenesis in peripheral CD4 T cells. Retrovirology. 2009;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bukrinskaya A, Brichacek B, Mann A, Stevenson M. Establishment of a functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcription complex involves the cytoskeleton. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2113–2125. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron PU, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 latency in resting CD4+ T cells depends on chemokine-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16934–16939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002894107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnittman SM, Lane HC, Greenhouse J, Justement JS, Baseler M, Fauci AS. Preferential infection of CD4+ memory T cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence for a role in the selective T-cell functional defects observed in infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6058–6062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chomont N, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. 2009;15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cayota A, Vuillier F, Scott-Algara D, Dighiero G. Preferential replication of HIV-1 in memory CD4+ subpopulation. Lancet. 1990;336:941. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helbert MR, Walter J, L'Age J, Beverley PC. HIV infection of CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.280-ce1170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roederer M, Raju PA, Mitra DK, Herzenberg LA. HIV does not replicate in naive CD4 T cells stimulated with CD3/CD28. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1555–1564. doi: 10.1172/JCI119318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spina CA, Prince HE, Richman DD. Preferential replication of HIV-1 in the CD45RO memory cell subset of primary CD4 lymphocytes in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1774–1785. doi: 10.1172/JCI119342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods TC, Roberts BD, Butera ST, Folks TM. Loss of inducible virus in CD45RA naive cells after human immunodeficiency virus-1 entry accounts for preferential viral replication in CD45RO memory cells. Blood. 1997;89:1635–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bubb MR, Spector I, Beyer BB, Fosen KM. Effects of jasplakinolide on the kinetics of actin polymerization. An explanation for certain in vivo observations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5163–5170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spector I, Shochet NR, Kashman Y, Groweiss A. Latrunculins: novel marine toxins that disrupt microfilament organization in cultured cells. Science. 1983;219:493–495. doi: 10.1126/science.6681676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hottiger M, Gramatikoff K, Georgiev O, Chaponnier C, Schaffner W, Hubscher U. The large subunit of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase interacts with beta-actin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:736–741. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rey O, Canon J, Krogstad P. HIV-1 Gag protein associates with F-actin present in microfilaments. Virology. 1996;220:530–534. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu B, Dai R, Tian CJ, Dawson L, Gorelick R, Yu XF. Interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid with actin. J Virol. 1999;73:2901–2908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2901-2908.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilk T, Gowen B, Fuller SD. Actin associates with the nucleocapsid domain of the human immunodeficiency virus Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:1931–1940. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1931-1940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niederman TM, Hastings WR, Ratner L. Myristoylation-enhanced binding of the HIV-1 Nef protein to T cell skeletal matrix. Virology. 1993;197:420–425. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper J, et al. Filamin A protein interacts with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein and contributes to productive particle assembly. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28498–28510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naghavi MH, et al. Moesin regulates stable microtubule formation and limits retroviral infection in cultured cells. EMBO J. 2007;26:41–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jimenez-Baranda S, et al. Filamin-A regulates actin-dependent clustering of HIV receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:838–846. doi: 10.1038/ncb1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia-Exposito L, et al. Gelsolin activity controls efficient early HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology. 2013;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo J, Wu Y. RPMA-based systematic mapping of the signaling network mediated by M-tropic HIV-1 gp120 in primary macrophages.. Nebraska Center for Virology Annual Meeting; Lincoin, NE. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Komano J, Miyauchi K, Matsuda Z, Yamamoto N. Inhibiting the Arp2/3 complex limits infection of both intracellular mature vaccinia virus and primate lentiviruses. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5197–5207. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nolen BJ, et al. Characterization of two classes of small molecule inhibitors of Arp2/3 complex. Nature. 2009;460:1031–1034. doi: 10.1038/nature08231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizvi SA, et al. Identification and characterization of a small molecule inhibitor of formin-mediated actin assembly. Chem Biol. 2009;16:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gurniak CB, Perlas E, Witke W. The actin depolymerizing factor n-cofilin is essential for neural tube morphogenesis and neural crest cell migration. Dev Biol. 2005;278:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Witke W, Sutherland JD, Sharpe A, Arai M, Kwiatkowski DJ. Profilin I is essential for cell survival and cell division in early mouse development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3832–3836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051515498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vauti F, Prochnow BR, Freese E, Ramasamy SK, Ruiz P, Arnold H- H. Arp3 is required during preimplantation development of the mouse embryo. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5691–5697. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–259. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dan C, Kelly A, Bernard O, Minden A. Cytoskeletal changes regulated by the PAK4 serine/threonine kinase are mediated by LIM kinase 1 and cofilin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32115–32121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohashi K, Nagata K, Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. Rho-associated kinase ROCK activates LIM-kinase 1 by phosphorylation at threonine 508 within the activation loop. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3577–3582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carlier MF, et al. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Derivery E, Gautreau A. Generation of branched actin networks: assembly and regulation of the N-WASP and WAVE molecular machines. Bioessays. 2010;32:119–131. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Danson CM, Pocha SM, Bloomberg GB, Cory GO. Phosphorylation of WAVE2 by MAP kinases regulates persistent cell migration and polarity. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4144–4154. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lebensohn AM, Kirschner MW. Activation of the WAVE complex by coincident signals controls actin assembly. Mol Cell. 2009;36:512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burkhardt JK, Carrizosa E, Shaffer MH. The actin cytoskeleton in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:233–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang Y, Burkhardt JK. T-cell-receptor-dependent actin regulatory mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:723–730. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nolz JC, et al. The WAVE2 complex regulates actin cytoskeletal reorganization and CRAC-mediated calcium entry during T cell activation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harmon B, Campbell N, Ratner L. Role of Abl kinase and the Wave2 signaling complex in HIV-1 entry at a post-hemifusion step. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000956. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aspenstrom P, Lindberg U, Hall A. Two GTPases, Cdc42 and Rac, bind directly to a protein implicated in the immunodeficiency disorder Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Curr Biol. 1996;6:70–75. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kolluri R, Tolias KF, Carpenter CL, Rosen FS, Kirchhausen T. Direct interaction of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein with the GTPase Cdc42. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5615–5618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Symons M, et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, a novel effector for the GTPase CDC42Hs, is implicated in actin polymerization. Cell. 1996;84:723–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Activation by Cdc42 and PIP(2) of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) stimulates actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1311–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peterson JR, Lokey RS, Mitchison TJ, Kirschner MW. A chemical inhibitor of N-WASP reveals a new mechanism for targeting protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10624–10629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201393198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peterson JR, et al. Chemical inhibition of N-WASP by stabilization of a native autoinhibited conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:747–755. doi: 10.1038/nsmb796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aldrich RA, Steinberg AG, Campbell DC. Pedigree demonstrating a sex-linked recessive condition characterized by draining ears, eczematoid dermatitis and bloody diarrhea. Pediatrics. 1954;13:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Derry JM, Ochs HD, Francke U. Isolation of a novel gene mutated in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Cell. 1994;78:635–644. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Villa A, et al. X-linked thrombocytopenia and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome are allelic diseases with mutations in the WASP gene. Nat Genet. 1995;9:414–417. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Devriendt K, et al. Constitutively activating mutation in WASP causes X-linked severe congenital neutropenia. Nat Genet. 2001;27:313–317. doi: 10.1038/85886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lorenzi R, Brickell PM, Katz DR, Kinnon C, Thrasher AJ. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein is necessary for efficient IgG-mediated phagocytosis. Blood. 2000;95:2943–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leverrier Y, et al. Cutting edge: the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein is required for efficient phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:4831–4834. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Orange JS, et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein is required for NK cell cytotoxicity and colocalizes with actin to NK cell-activating immunologic synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11351–11356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162376099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gismondi A, et al. Impaired natural and CD16-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity in patients with WAS and XLT: ability of IL-2 to correct NK cell functional defect. Blood. 2004;104:436–443. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bouma G, Burns S, Thrasher AJ. Impaired T-cell priming in vivo resulting from dysfunction of WASp-deficient dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;110:4278–4284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Galjart N, De Zeeuw CI. LIMK1 and CLIP-115: linking cytoskeletal defects to Williams syndrome. Bioessays. 2004;26:141–150. doi: 10.1002/bies.10402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Williams JC, Barratt-Boyes BG, Lowe JB. Supravalvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1961;24:1311–1318. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.6.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beuren AJ, Apitz J, Harmjanz D. Supravalvular aortic stenosis in association with mental retardation and a certain facial appearance. Circulation. 1962;26:1235–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.26.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Preus M. Differential diagnosis of the Williams and the Noonan syndromes. Clin Genet. 1984;25:429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1984.tb02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ewart AK, et al. Hemizygosity at the elastin locus in a developmental disorder, Williams syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;5:11–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Korenberg JR, et al. VI. Genome structure and cognitive map of Williams syndrome. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(Suppl):89–107. doi: 10.1162/089892900562002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peoples R, et al. A physical map, including a BAC/PAC clone contig, of the Williams-Beuren syndrome--deletion region at 7q11.23. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:47–68. doi: 10.1086/302722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li DY, et al. Elastin point mutations cause an obstructive vascular disease, supravalvular aortic stenosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1021–1028. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tassabehji M, et al. Elastin: genomic structure and point mutations in patients with supravalvular aortic stenosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1029–1036. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meng Y, et al. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;35:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Croft DR, et al. p53-mediated transcriptional regulation and activation of the actin cytoskeleton regulatory RhoC to LIMK2 signaling pathway promotes cell survival. Cell Res. 2011;21:666–682. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Davila M, Frost AR, Grizzle WE, Chakrabarti R. LIM kinase 1 is essential for the invasive growth of prostate epithelial cells: implications in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36868–36875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoshioka K, Foletta V, Bernard O, Itoh K. A role for LIM kinase in cancer invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7247–7252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232344100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bagheri-Yarmand R, Mazumdar A, Sahin AA, Kumar R. LIM kinase 1 increases tumor metastasis of human breast cancer cells via regulation of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2703–2710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Vlecken DH, Bagowski CP. LIMK1 and LIMK2 are important for metastatic behavior and tumor cell-induced angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells. Zebrafish. 2009;6:433–439. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2009.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ma Q-L, Yang F, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. PAK in Alzheimer disease, Huntington disease and X-linked mental retardation. Cell Logist. 2012;2:117–125. doi: 10.4161/cl.21602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yi F, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 Infection by Novel LIM Kinase Inhibitors.. The Fourth Virginia University AIDS Research Consortium (VUARC) Meeting; Fairfax, VA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Carter GC, Bernstone L, Baskaran D, James W. HIV-1 infects macrophages by exploiting an endocytic route dependent on dynamin, Rac1 and Pak1. Virology. 2011;409:234–250. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tybulewicz VLJ, Henderson RB. Rho family GTPases and their regulators in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:630–644. doi: 10.1038/nri2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Raman D, Sobolik-Delmaire T, Richmond A. Chemokines in health and disease. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:575–589. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bleul CC, et al. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Oberlin E, et al. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vandekerckhove L, Verhofstede C, Vogelaers D. Maraviroc: integration of a new antiretroviral drug class into clinical practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:1187–1190. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hendrix CW, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of AMD3100, a selective CXCR4 receptor inhibitor, in HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1253–1262. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000137371.80695.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Damas JK, Landro L, Fevang B, Heggelund L, Froland SS, Aukrust P. Enhanced levels of the CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 in HIV infection: correlation with viral load, disease progression and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23:135–138. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831cf595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Damås JK, et al. Enhanced levels of CCL19 in patients with advanced acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:492–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cameron PU, et al. Latent HIV infection can be established in resting CD4+ T-cells in vitro following incubation with multiple diverse chemokines which facilitate nuclear import of the pre-integration complex. 4th International Workship in HIV Persistence During Therapy. 2009 Dec 8-11; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Campbell GR, Spector SA. CCL2 increases X4-tropic HIV-1 entry into resting CD4+ T cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30745–30753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804112200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3652–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ansari AW, Bhatnagar N, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schmidt RE, Heiken H. Host chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-2 (CCL2) is differentially regulated in HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1443–1451. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Proudfoot AE, et al. Extension of recombinant human RANTES by the retention of the initiating methionine produces a potent antagonist. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2599–2603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Simmons G, et al. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity in macrophages and lymphocytes by a novel CCR5 antagonist. Science. 1997;276:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lederman MM, et al. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in rhesus macaques through inhibition of CCR5. Science. 2004;306:485–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1099288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Anand AR, Zhao H, Nagaraja T, Ganju RK. The N-terminal fragment of Slit2 inhibits HIV infection by modulating the actin cytoskeleton pathway. The 2012 Cold Spring Harbor Meeting on Retroviruses. 2012 May-May;:41. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Anand AR, Zhao H, Nagaraja T, Robinson LA, Ganju RK. N-terminal Slit2 inhibits HIV-1 replication by regulating the actin cytoskeleton. Retrovirology. 2013;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhang X, Yu J, Kuzontkoski PM, Zhu W, Li DY, Groopman JE. Slit2/Robo4 signaling modulates HIV-1 gp120-induced lymphatic hyperpermeability. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002461. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wu Y, Yoder RAC, Kelly J, Yu D. Composition and methods for detecting and treating HIV infections. 2006 U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 60/797,745.

- 130.Guo J, et al. Genistein interferes with SDF-1- and HIV-mediated actin dynamics and inhibits HIV infection of resting CD4 T cells. Retrovirology. 2013;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stantchev TS, Markovic I, Telford WG, Clouse KA, Broder CC. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein blocks HIV-1 infection in primary human macrophages. Virus Res. 2007;123:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kaufman PB, Duke JA, Brielmann H, Boik J, Hoyt JE. A comparative survey of leguminous plants as sources of the isoflavones, genistein and daidzein: implications for human nutrition and health. J Altern Complement Med. 1997;3:7–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.1997.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Raynal NJ, Momparler L, Charbonneau M, Momparler RL. Antileukemic activity of genistein, a major isoflavone present in soy products. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:3–7. doi: 10.1021/np070230s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Raynal NJ, Charbonneau M, Momparler LF, Momparler RL. Synergistic effect of 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine and genistein in combination against leukemia. Oncol Res. 2008;17:223–230. doi: 10.3727/096504008786111356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lakshman M, et al. Dietary genistein inhibits metastasis of human prostate cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2024–2032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Takimoto CH, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of unconjugated soy isoflavones administered to individuals with cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1213–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Poznansky MC, Olszak IT, Foxall R, Evans RH, Luster AD, Scadden DT. Active movement of T cells away from a chemokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:543–548. doi: 10.1038/75022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shieh DB, Li RY, Liao JM, Chen GD, Liou YM. Effects of genistein on beta-catenin signaling and subcellular distribution of actin-binding proteins in human umbilical CD105-positive stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:423–434. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.De Corte V, Gettemans J, Vandekerckhove J. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate specifically stimulates PP60(c-src) catalyzed phosphorylation of gelsolin and related actin-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.De Corte V, Demol H, Goethals M, Van Damme J, Gettemans J, Vandekerckhove J. Identification of Tyr438 as the major in vitro c-Src phosphorylation site in human gelsolin: a mass spectrometric approach. Protein Sci. 1999;8:234–241. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhai L, Zhao P, Panebra A, Guerrerio AL, Khurana S. Tyrosine phosphorylation of villin regulates the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36163–36167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bretscher A. Regulation of cortical structure by the ezrin-radixin-moesin protein family. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huang C, Liu J, Haudenschild CC, Zhan X. The role of tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin in the locomotion of endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25770–25776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Head JA, et al. Cortactin tyrosine phosphorylation requires Rac1 activity and association with the cortical actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3216–3229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fan L, et al. Actin depolymerization-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin: the role of Fer kinase. Biochem J. 2004;380:581–591. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Chang F, Lemmon C, Lietha D, Eck M, Romer L. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Rac1: a role in regulation of cell spreading. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Cory GO, Garg R, Cramer R, Ridley AJ. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 291 enhances the ability of WASp to stimulate actin polymerization and filopodium formation. Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45115–45121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Jia Z, Zhen W, Velayutham Anandh Babu P, Liu D. Phytoestrogen genistein protects against endothelial barrier dysfunction in vascular endothelial cells through PKA-mediated suppression of RhoA signaling. Endocrinology. 2013;154:727–737. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Severson RK, Nomura AM, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN. A prospective study of demographics, diet, and prostate cancer among men of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1857–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Shimizu H, Ross RK, Bernstein L, Yatani R, Henderson BE, Mack TM. Cancers of the prostate and breast among Japanese and white immigrants in Los Angeles County. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:963–966. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Adlercreutz H, Markkanen H, Watanabe S. Plasma concentrations of phyto-oestrogens in Japanese men. Lancet. 1993;342:1209–1210. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92188-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Miltyk W, et al. Lack of significant genotoxicity of purified soy isoflavones (genistein, daidzein, and glycitein) in 20 patients with prostate cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:875–882. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]