Abstract

3-Hydroxycyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid (HOCPCA, 1) is a potent ligand for the high-affinity GHB binding sites in the CNS. An improved synthesis of 1 together with a very efficient synthesis of [3H]-1 is described. The radiosynthesis employs in situ generated lithium trimethoxyborotritide. Screening of 1 against different CNS targets establishes a high selectivity and we demonstrate in vivo brain penetration. In vitro characterization of [3H]-1 binding shows high specificity to the high-affinity GHB binding sites.

INTRODUCTION

γ-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB, Figure 1) is an endogenous substance that is present in micromolar concentrations in the mammalian brain. It is a metabolite of the major inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Figure 1), but is also believed to be a neuromodulator on its own1 although the specific function of GHB remains to be elucidated. GHB is administered orally for the treatment of narcolepsy (sodium oxybate)2 and alcoholism.3 GHB is tasteless and odorless and combined with its central nervous system (CNS) effects (mild euphoria, sedation, respiratory depression and eventually coma in high doses) it is a hazardous drug of abuse (fantasy). In the CNS, GHB binds to both low-affinity and high-affinity binding sites.1 The low-affinity site is believed to be identical to the GABA orthosteric site at the metabotropic GABAB receptor as high dose effects of GHB (micromolar in the brain) is prevented by preincubating with a GABAB receptor antagonist3 and several prominent GHB-induced effects are absent in GABAB knockout mice.4 However, when comparing the effect of GHB with that of the GABAB agonist baclofen (Figure 1) in, e.g., c-Fos expression studies5 and behavioral studies,6 it is clear that the two compounds have different pharmacological profiles. Thus, GHB effects may also be mediated by non-GABAB receptors. The fact that GHB high-affinity binding sites are preserved in brains of GABAB knockout mice,4 make them likely receptor candidates and has prompted the uncovering of their identity. Using photoaffinity labeling combined with proteomic analysis and molecular pharmacology studies, we recently reported that α4β1-3δ ionotropic GABAA receptors correlate with the GHB high-affinity sites.7 In order to acquire a more complete understanding of the physiological relevance of GHB high-affinity binding sites in the CNS, and particularly the nanomolar effects mediated by GHB at the α4β1δ receptors, better tool compounds and further pharmacological investigations are needed.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the two neuroactive substances GHB and GABA. HOCPCA (1) and NCS-382 bind selectively to the high-affinity GHB binding site. Baclofen is a selective GABAB agonist.

We have previously described 3-hydroxycyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid (HOCPCA, 1, Figure 1) as a selective ligand for the high-affinity GHB binding site (27 times higher affinity than GHB itself), and, importantly, with no affinity for the GABAB receptor. Given the close structural relationship to GHB and its relatively small size, 1 is a highly attractive compound to investigate GHB-like pharmacology. We therefore decided to explore synthetic routes for incorporation of hydrogen and carbon isotopes into 1, and at the same time provide a more feasible and preparative synthesis of 1, which is needed to facilitate in vivo studies. At present [3H](E,RS)-(6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5-hydroxy-5H-benzocyclohept-6-ylidene)acetic acid ([3H]-NCS-382) is the standard radioligand in binding experiments for the high-affinity GHB binding site.8 NCS-382 (Figure 1) is a putative antagonist8 at the high–affinity GHB binding site with a Ki 14 times lower than that of GHB.9 The higher affinity of 1 compared to NCS-382,9 and closer structural relationship to GHB underscores the relevance of developing a better preparative and radiolabeling procedure. This will provide a better alternative to the only available radiolabeled agonist [3H]GHB, which has several caveats, both in terms of selectivity due to its affinity for the GABAB receptor, and in terms of its susceptibility to metabolism and uptake.10

Here, we describe a highly improved preparative synthesis of 1 and the synthesis of tritium labeled 1. Furthermore, the stability of 1 and [3H]-1 are evaluated, binding competition studies using [3H]-1 are presented and the selectivity profile of 1 is investigated. Finally, the brain penetration of GHB, 1 and NCS-382 is investigated in vivo.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Improved synthesis of 1

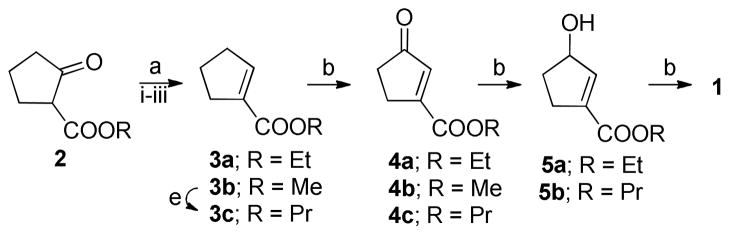

The previously9 reported synthesis of 1 is outlined in Scheme 1. Reduction of the starting material (2) followed by mesylation and elimination gave α,β-unsaturated ethyl ester (3a) in 53% yield.

Scheme 1. Previous synthesis route to 1 and its carbonyl precursor 9a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C – rt, 2.5h, (ii) CH3SO2Cl, Py, rt, 3h, (iii) Et3N, CHCl3, reflux, 23h; (b) CrO3, Ac2O, AcOH, rt, 30 min; (c) NaBH4, CeCl3, MeOH, 0°C, 30 min; (d) Na2CO3, 50 °C, 16h; (e) 1-propanol, H2SO4, reflux, 1h.

Oxidation of 3a with 3 eq. of CrO3 gave 4a in varying yields below 39%. Successful Luche reduction gave 5a and final deprotection with sodium carbonate gave the product 1 as hygroscopic crystals. The overall yield of the 6-step synthesis was 18%. However, this route posed several problems as a preparative synthesis, i.e. varying yields, tedious purification in particular in the oxidation of 3a, and a hygroscopic end product that is unstable during storage.

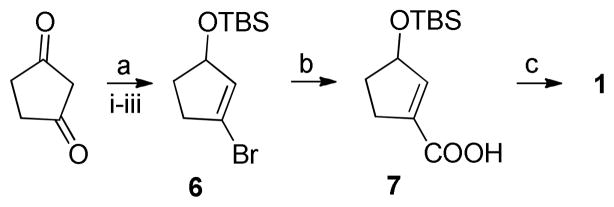

In light of the potential of 1 as a pharmacological tool for future in vivo and ex vivo studies, we wanted to develop a more suitable synthesis of 1 that could circumvent these obstacles and generate large quantities of 1. The new synthetic route to 1 is outlined in Scheme 2. First 1,3-cyclopentanedione was brominated with dibromo-triphenylphosphine and triethylamine.11 It was crucial for a high yield to use freshly distilled triethylamine dried over LiAlH4, whereas sublimation (110 °C, 0.2 mbar) of the commercial brownish 1.3-cyclopentanedione to white crystals did not improve the yield. Luche reduction with NaBH4 in methanol gave the alcohol that was immediately TBS-protected to give 6 in 86% overall yield.

Scheme 2. New synthesis route to 1a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) Br2PPh3, benzene, Et3N, rt, 18h, (ii) NaBH4, CeCl3, MeOH, 0°C – rt, 2.5h, (iii) TBS-Cl, DMAP, imidazole, DCM, rt, 16h; (b) t-BuLi, THF, −78 – −50 °C, 2h, −78 °C, CO2(g), 20 min; (c) H2SiF6 (aq 23%), CH3CN, rt, 1h.

Metal-halogen exchange of 6 using t-BuLi followed by addition of CO2 (g) afforded the carboxylic acid 7 in 78% yield. Finally, deprotection of the TBS-protected alcohol using an aqueous solution of H2SiF6 as described by Pilcher and DeShong12 gave 1 as white crystals in 75% yield upon recrystallization. The product was stable as the free acid as well as the sodium-salt. This new synthetic route is high yielding (56% overall), includes more simple purifications and produces a non-hygroscopic stable product without the use of chromic acid. The route is also applicable for late-stage isotopic carbon labeling of 1, since labeled CO2(g) can be employed when incorporating the carboxylic acid group. Alternatively, the bromide 6 can be transformed to the corresponding pinacol boronic ester and treated with [11C]CO2(g) in the presence of CuI/crypt-222/KF as recently described by Riss et al.13 On the other hand, the route is not stereoselective and provide both enantiomers.

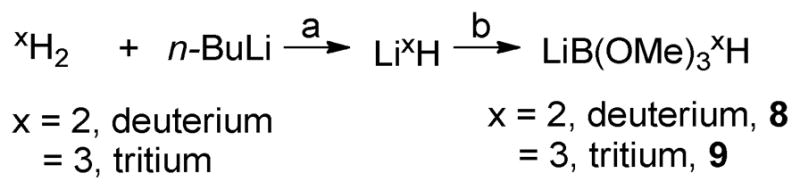

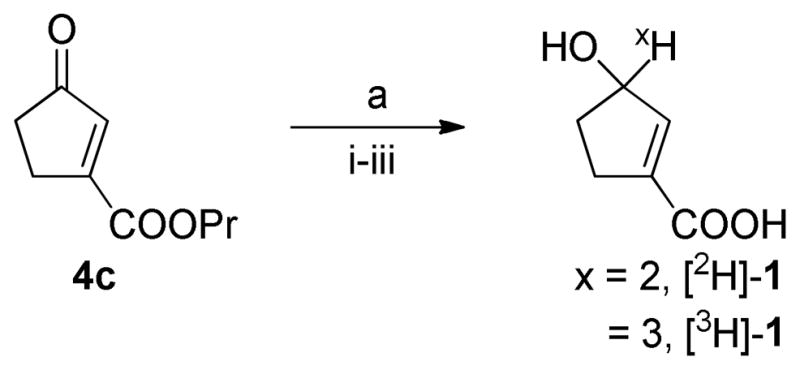

Tritium labeling

The previously reported synthesis of 1 outlined in Scheme 1 was a good starting point for a route to tritium labeled 1 as reduction of the α, β-unsaturated ketone (4) enabled introduction of tritium late in the synthesis. Still some optimization of this route was feasible. 3b is commercially available but volatility of both 3b and 4b compromised the yield in the first step and 3b was therefore transesterified to the propylester 3c in 70% yield. Attempts to replace the excess amount of chromic acid with KMnO414 or TBHP/Pd(OH)C15 were unsuccessful. The use of catalytic amounts of Mn(OAc)2·4H2O16 was at first glance successful (75% yield), but unfortunately an unidentified impurity not visible by NMR, affected the course of the following reduction negatively and the oxidation was therefore performed with chromic acid to afford 4c. The Luche reduction (1 eq. of NaBH4 in MeOH in the presence of CeCl3) gave the alcohol 5b in 98% yield (supporting information, Table S1). To prepare [3H]-1 with a maximal specific activity we decided to screen the reaction conditions using borodeuterides prepared in situ from deuterium gas instead of using commercial deuterides. In the literature a broad spectrum of in situ prepared borodeuterides17, 18 and tritides,19, 20 respectively are described. To suppress the risk of reduction of the double bond and ester group we were especially interested in less reactive borodeuterides. As demonstrated by Zippi et al.19 LiB(OMe)32H (8) can be readily generated from Li2H by addition of trimethoxyborate (Scheme 3). Lithium deuteride is formed by the treatment of a n-BuLi-TMEDA solution under gaseous 2H2 atmosphere17 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the lithiumboronic reducing reagenta.

aReagents and conditions: (a) TMEDA, 2h, room temperature; (b) B(OMe)3, 30 min, room temperature.

The yield of in situ generated borodeuteride (8) was determined indirectly using 4-anisaldehyde as a trapping agent in independent reactions. The reaction was carried out under various ratios (1:1, 2:1 and 1:2) of (8) (theoretically generated amounts based on n-BuLi) and anisaldehyde and the yield of 8 was determined by HPLC and 1H-NMR to be in the range of 40–47% in all three cases. That is in accordance with the yield of Li3H (35%) reported by Zippi et al.19 For radiation safety reasons during the 3H-labeling of 1, it was desirable to perform the reduction with borotritide and the ester hydrolysis of 4c in one-pot. Therefore, upon lyophilization of the solvent aq. NaOH was added and hydrolysis of the propylester gave [2H]-1 (Scheme 4). The lyophilization was crucial as the yield dropped from 88% to 15% if omitted. Next the reaction conditions for the reduction of 4c (Scheme 4) was investigated (See supporting information Table S1).

Scheme 4. Deuterium and tritium-labeling of 1a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) 8 or 9, THF, room temperature, 2h, room temperature, lyophilized (ii) 1M NaOH, 1h, room temperature (iii) 1M HCl.

The protic solvent MeOH of the original experiment could not be exchanged with EtOH in the presence of CeCl3. Actually the presence of CeCl3 apparently resulted in an increased amount of hydrolyzed 4c, and could successfully be omitted. In the absence of CeCl3 both DMF and even the easily lyophilizable solvent THF could be used.

Lowering of the reaction temperature to 0 °C or −78 °C did not improve the deuterated yield nor suppressed the hydrolysis of the ketone. For comparison in situ synthesized Li2H and LiB2H4 (see supporting information) were also attempted, but resulted in lower yields and more complex reaction mixtures.

Finally, the best conditions (LiB(OMe)32H, THF, room temperature) was used to prepare [3H]-1 (Scheme 4). To achieve full conversion of 4c excess amounts (1.8 eq.) of LiB(OMe)33H was used. Reduction of 4c gave the 3H-labeled propylester in 95% yield according to HPLC (245 nm). Subsequent hydrolysis gave the desired product [3H]-1 (97%, 245 nm). We determined the amounts of prepared [3H]-1 to 637 mCi with a specific activity of 28.9 Ci/mmol (determined by MS and HPLC/LSC, which accounts for close to 1 tritium/molecule) and a radio chemical purity (RCP) and chemical purity > 99% after purification (HPLC, Figure S11).

Stability

Both 1 and [3H]-1 was subjected to stability testing by HPLC (area%, 245 nm). The rate of decomposition of 1 was tested at both room temperature and −30±2°C in MilliQ water (2 mg/mL). pH of this solution was 3.5. At −30°C compound 1 proved completely stable (1 year and 4 months after formulation) and at room temperature only a minor decomposition of 1 was observed (100% at day 0 to 96% at day 35 and 88% at day 99). The stability of [3H]-1 was investigated in four different formulations for the protection against radiolysis (see supporting information). The best stability of [3H]-1 was found to be a solution of 1 mCi/mL in ethanol or in an aqueous solution of gentisic acid (50 mM).

Binding studies

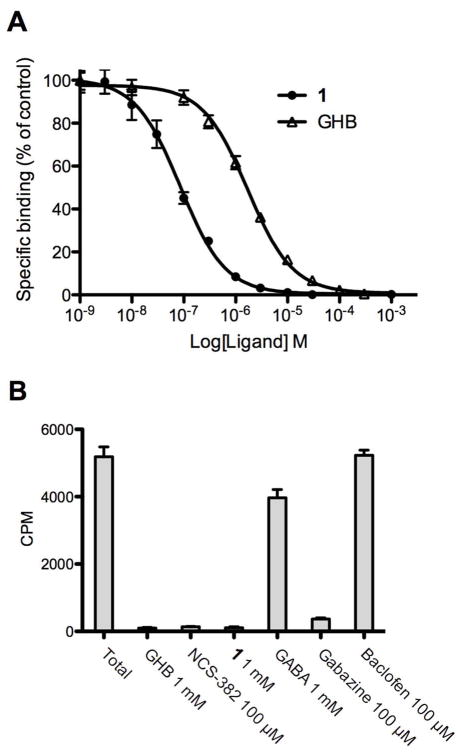

Binding of [3H]-1 to rat cortical membranes was investigated using assay conditions previously described for [3H]NCS-3829 with GHB (1 mM) for determining non-specific binding (Figure 2A). IC50 [pIC50±SEM] values for 1, sodium salt of 1 and GHB were respectively 0.073 μM [7.14±0.02], 0.116 μM [6.93±0.01] and 1.14 μM [5.94±0.06]. This is in relative accordance with values obtained in the comparable [3H]NCS-382 binding assay (0.16 μM and 4.3 μM, respectively).9 As expected, [3H]-1 binding was inhibited by the GHB-selective ligand NCS-382 and the GABAA antagonist gabazine7, 21 but notably not by baclofen and GABA at high concentrations.7, 9 These data suggest that [3H]-1 selectively labels the high-affinity GHB binding site. The selectivity was further explored in The National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (NIMH-PDSP) (Supplementary Table S2) where 1 was found to be more than 100 times selective for the [3H]-1 binding site over 45 different receptors and transporters. The high selectivity of 1 combined with a ligand efficiency22 of 1.05 kcal/mol establish 1 as a highly interesting compound for further studying the high-affinity GHB binding site.

Figure 2.

(A) Concentration-dependent inhibition of [3H]-1 binding (10 nM) to rat cerebrocortical membranes by GHB and 1. Results are expressed as mean (SD of a single representative experiment performed in triplicate). Three additional experiments gave similar results. (B) Displacement of 10 nM [3H]-1 binding to rat cerebrocortical membranes by 1 mM GHB, 100 μM NCS-382, 1 mM 1, 1 mM GABA, 100 μM gabazine and 100 μM baclofen. Results are expressed as mean CPM (SD of a single representative experiment performed in triplicate) and were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Brain penetration studies

The brain to plasma distribution ratio of GHB, 1 and NCS-382 was investigated acutely in mice 30 minutes after oral administration of 10 mg/kg. All three compounds were found to be brain penetrant reflected by their brain to plasma ratios of 0.20, 0.37 and 0.38 for GHB, 1 and NCS-382, respectively. Considering the carboxylic acid group shared by all three compounds, often associated with restricted passive brain penetration, these results may suggest an involvement of active transport across the blood-brain barrier. This hypothesis was supported by assessment of the in vitro permeability using MDCK-MDR1 cells23 which showed that GHB, 1 and NCS-382 all exhibited very low passive permeability. Thus, after spiking of test compounds on either the apical or basal side of the cell monolayers, no compound could be detected at the respective receiver sides.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion we have developed a new preparative synthetic route to 1 that can be scaled up with a high and reproducible overall yield. The new synthesis can readily be developed further for carbon labeling. Compound 1 is stable during storage and has a favorable selectivity profile when tested against other relevant targets. Furthermore, compound 1 was successfully tritium labeled using in situ generated lithium trimethoxy-borotritide. The incorporation of one tritium atom proceeded in high radioactive yield, with close to theoretical specific activity and with high radiochemical purity. Binding of [3H]-1 could be displaced by GHB and 1 in a concentration-dependent manner and not by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen. This new radioligand will be useful for further understanding the molecular mechanism of GHB at its high-affinity binding site and α4βδ GABAA receptors and for elucidating the pharmacology of the GHB system in the mammalian CNS, given the brain permeability of 1, for instance through ex vivo or in vivo labeling of the binding sites with positron-emitting or other isotopes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

[3H]-3-Hydroxycyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid ([3H]-1)

Career free 3H2 (13.8 Ci) trapped on a uranium bed (as uranium tritide) was released by heating (500 °C) and directed in a tritium manifold into a dried reaction vial (1 mL 2 necked round bottom flask). N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylethylenediamine (50 μL) was added. n-Butyl lithium (100 μL, 160 μmol, 1.6M in hexane) was added drop wise and within 10 min a white precipitate of Li3H was formed. After 2 h of vigorous stirring trimethyl borate (18 μl, 160 μmoles) was added and the reaction was stirred for 30 min to generate LiB(OMe)33H. A solution of propyl 3-oxocyclopent-1-en carboxylate (4c) (15 mg, 89 μmol) in THF (300 μL) was added drop wise and the reaction was stirred for 2 h. Solvents were lyophilized. Water (500 μL) was added and a sample showed predominantly [3H]-5b by HPLC analysis (95%, 245 nm). Aq. NaOH (2 M, 100 μl) was added and the reaction was stirred for 1 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized with 1N HCl to reach pH 6. Water was lyophilized and the solid residue dissolved in accurately amounts of water. 1/10 of the crude mixture was used for qualitative and quantitative analysis (see SI). Preparative HPLC gave [3H]-1 ((97%, 245 nm), 637 mCi, 28.9 Ci/mmol) as white solid. 3H NMR (320 MHz, DMSO-D6/H2O 10:1) δ 4.71 (s). MS (ESI): 128.9 (100, M-1).

3-Hydroxycyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid (1)

3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)cyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid (3.17 g, 13.08 mol) was dissolved in acetonitrile (130 mL) in a polypropylene vial and H2SiF6 (aq, 20–25 %wt, 2.3 mL, 3.9 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 1h at room temperature. Sat. Na2CO3 (100 mL) and water (50 mL) were added and the aqueous phase was washed with diethyl ether (2 × 20 mL). The aqueous phase was made acidic by the addition of HCl (aq, 4M) and extracted with ethyl acetate (4 × 150 mL). The combined organic phase was dried (MgSO4) and the solvent removed in vacuo to give a white solid. CC (2:1 heptane/ethyl acetate + 2% AcOH) gave a white solid. Recrystallization (acetonitrile) gave the product as white crystals (1.26 g, 75%). Mp 134–136°C. 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.71 (m, 1H), 2.30–2.48 (m, 2H), 2.62–2.70 (m, 1H), 4.86–4.91 (m, 1H), 6.63–6.65 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 30.81, 34.23, 77.65, 139.93, 144.72, 168.62. Anal. Calcd for C6H8O3: C, 56.24; H, 6.29. Found: C, 56.34; H, 6.17. LC-MS (system B): (M-H2O)H+: 111.1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (S.B.V.), the Danish Medical Research Council (T.B.) and the Drug Research Academy (T.B.). AM’s fellowship at the Hevesy laboratory was founded by The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (C6/CZR/11001). This work was supported by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (RVO: 61388963) We gratefully acknowledge the Prague institute for access to tritium NMR. Dr. Steve White is kindly acknowledged for generously organizing the NIMH-PDSP compound screen (contract # HHSN-271-2008-00025-C). The NIMH PDSP is Directed by Bryan L. Roth MD, PhD at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Project Officer Jamie Driscol at NIMH, Bethesda MD, USA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GHB

γ-hydroxybutyrate

- HOCPCA

3-Hydroxycyclopent-1-enecarboxylic acid

- NCS-382

(2E)-(5-hydroxy-5,7,8,9-tetrahydro-6H-benzo[a][7]annulen)-6-ylidene ethanoic acid

Footnotes

Supporting information. Experimental data for compounds (3c, 4c, 6, 7,[2H]-5b, [2H]-1), description of stability studies, in vitro pharmacological methods and NIMH-PDSP screening results. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bernasconi R, Mathivet P, Bischoff S, Marescaux C. γ-hydroxybutyric acid: an endogenous neuromodulator with abuse potential? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drasbek KR, Christensen J, Jensen K. γ-hydroxybutyrate - a drug of abuse. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter LP, Koek W, France CP. Behavioral analyses of GHB: receptor mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaupmann K, Cryan JF, Wellendorph P, Mombereau C, Sansig G, Klebs K, Schmutz M, Froestl W, van der Putten H, Mosbacher J, Bräuner-Osborne H, Waldmeier P, Bettler B. Specific γ-hydroxybutyrate-binding sites but loss of pharmacological effects of γ-hydroxybutyrate in GABAB(1)-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2722–2730. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nieuwenhuijzen PS, McGregor IS, Hunt GE. The distribution of γ-hydroxybutyrate-induced Fos expression in rat brain: Comparison with baclofen. Neuroscience. 2009;158:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koek W, Carter LP, Lamb RJ, Chen W, Wu H, Coop A, France CP. Discriminative stimulus effects of γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) in rats discriminating GHB from baclofen and diazepam. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:170–179. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Absalom N, Eghorn LF, Villumsen IS, Karim N, Bay T, Olsen JV, Knudsen GM, Bräuner-Osborne H, Frølund B, Clausen RP, Chebib M, Wellendorph P. α4βδ GABAA receptors are high-affinity targets for γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13404–13409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204376109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maitre M, Hechler V, Vayer P, Gobaille S, Cash CD, Schmitt M, Bourguignon JJ. A specific γ-hydroxybutyrate receptor ligand possesses both antagonistic and anticonvulsant properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:657–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wellendorph P, Høg S, Greenwood JR, de Lichtenberg A, Nielsen B, Frølund B, Brehm L, Clausen RP, Bräuner-Osborne H. Novel Cyclic γ-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) Analogs with High Affinity and Stereoselectivity of Binding to GHB Sites in Rat Brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:346–351. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta AK, Muschaweck NM, Maeda DY, Coop A, Ticku MK. Binding characteristics of the γ-hydroxybutyric acid receptor antagonist [3H](2E)-(5-Hydroxy-5, 7, 8, 9-tetrahydro-6H-benzo [α][7] annulen-6-ylidene) ethanoic acid in the rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:1148–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marson CM, Farrand LD, Brettle R, Dunmur DA. Highly efficient syntheses of 3-aryl-2-cycloalken-1-ones and an evaluation of their liquid crystalline properties. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:4377–4381. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilcher AS, DeShong P. Improved protocols for the selective deprotection of trialkylsilyl ethers using fluorosilicic acid. J Org Chem. 1993;58:5130–5134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riss PJ, Lu S, Telu S, Aigbirhio FI, Pike VW. CuI-catalyzed 11C carboxylation of boronic acid esters: a rapid and convenient entry to 11C-labeled carboxylic acids, esters, and amides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:2698–2702. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams GJ, Hunter NR. Situselective a′-acetoxylation of some α,β-enones by manganic acetate oxidation. Can J Chem. 1976;54:3830–3832. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu JQ, Corey EJ. A mild, catalytic, and highly selective method for the oxidation of α,β-enones to 1,4-enediones. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3232–3233. doi: 10.1021/ja0340735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shing TK, Yeung YY, Su PL. Mild manganese (III) acetate catalyzed allylic oxidation: Application to simple and complex alkenes. Org Lett. 2006;8:3149–3151. doi: 10.1021/ol0612298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zippi EM. Lithium Hydride and Lithium Trimethoxy-borohydride: A Comparative Study of Their Reducing Power. Synthetic commun. 1994;24:2515–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnamurthy S, Brown HC. Selective reductions. 31. Lithium triethylborohydride as an exceptionally powerful nucleophile. A new and remarkably rapid methodology for the hydrogenolysis of alkyl halides under mild conditions. J Org Chem. 1983;48:3085–3091. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zippi EM, Andres H, Morimoto H, Williams PG. Preparation and Use of Lithium Tritide and Lithium Trimethoxyborotritide. Synthetic commun. 1995;25:2685–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saljoughian M. Synthetic tritium labeling: reagents and methodologies. Synthesis. 2002:1781–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabbatini P, Wellendorph P, Høg S, Pedersen MH, Bräuner-Osborne H, Martiny L, Frølund B, Clausen RP. Design, synthesis, and in vitro pharmacology of new radiolabeled γ-hydroxybutyric acid analogues including photolabile analogues with irreversible binding to the high-affinity γ-hydroxybutyric acid binding sites. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6506–6510. doi: 10.1021/jm1006325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopkins AL, Groom CR, Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:430–431. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Risgaard R, Ettrup A, Balle T, Dyssegaard A, Hansen HD, Lehel S, Madsen J, Pedersen H, Püschl A, Badolo L, Bang-Andersen B, Knudsen GM, Kristensen JL. Radiolabelling and PET brain imaging of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist Lu AE43936. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.