Abstract

Objective

Individuals with alcohol problems often receive pressure to change their drinking. However, when they enter treatment it is unclear how often it is because of the pressure they received or other reasons.

Method

A secondary analysis was conducted using four cross sectional National Alcohol Surveys (NASs) collected at 5-year intervals between 1995 and 2010. Treatment seekers (N=476) were interviewed about 1) all reasons for seeking treatment, 2) their primary reason, 3) lifetime heavy drinking, and 4) whether they ever received pressure from six different sources (spouse, family, friends, doctor, work and police).

Results

Over 90% of the sample received pressure from at least one source. Thirty-four percent identified legal problems/felt forced as their primary reason for seeking treatment. Other primary reasons included a desire to improve relationships (25%) and health (15%). When asked about all reasons, 46% endorsed five or more reasons and 74% included legal problems/felt forced. When pressure was received from police it was often the primary reason for seeking treatment. When pressure was received from physicians or work, legal problems/felt forced was less likely to be the primary reason. Most reasons, including legal problems/felt forced, did not change significantly over time.

Conclusions

A primary reason for seeking alcohol treatment is drinking-related legal problems or feeling forced. However, legal problems/feeling forced occurs along with a variety of additional reasons. Future research should assess pathways between receipt of pressure from different sources, recognition of different types of problems, and reasons given for seeking treatment.

Keywords: treatment entry, alcohol services, reasons for seeking help, treatment barriers, drinking Pressure

Introduction

There is an urgent need to improve treatment entry among individuals with alcohol use disorders. In 2007 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) conducted a national survey on the need for alcohol treatment, which was defined as meeting criteria for a DSM IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence or abuse. Based on a sample of 67,870, SAMHSA estimated that over 19 million individuals needed treatment, yet only 8.1% of that number received it (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Office of Applied Studies, 2009). Over 87% of those not receiving treatment did not perceive a need for it. Similar findings were reported by Oleski et al (2010) who analyzed the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions survey (N=43,093). They reported that nearly one-third of the sample met DSM IV criteria for a lifetime alcohol use disorder, yet 81% of these individuals did not seek treatment because they did not perceive a need for it.

Because individuals with alcohol problems frequently do not recognize a need for help, the role of external pressure to change drinking has received attention from policy makers and researchers. For example, (Schmidt &Weisner, 1993) described how coercion from the criminal justice system increased treatment entry over the 1980’s. In a summary of institutional coercion McLellan (2006) conclude that 59% of clients entering U.S. treatment programs received a mandate from the criminal justice system.

Studies documenting pressure to change drinking are not limited to treatment seeking samples. Using general population samples between 1984 and 2005 (pooled N = 16,241) Polcin et al (2012) studied current drinkers who received pressure during the past 12 months to cut down or act differently when they drank. Receipt of pressure ranged from 16% in 1990 to 8% in 2005. The most common sources of pressure were family and friends. Individuals who received pressure were frequent heavy drinkers and those who had had experienced more alcohol-related harm (e.g., medical problems, legal problems, and family conflict). Using the same datasets, Korcha et al. (under review) reported that those who received pressure from formal or informal sources were more likely to seek help than those not receiving pressure. Individuals who received pressure about their drinking were 5.4 times more likely than those who did not receive pressure to seek help. The regression analysis controlled for demographics, heavy drinking, alcohol-related harm, and beliefs about drinking.

Some studies assessing pressure among treatment samples have adopted a broader view of pressure than the typical comparison of criminal justice coerced versus voluntary. For example, Polcin and Beattie (2007) used a measure of pressure defined as a suggestion to get treatment to study 698 individuals entering treatment for alcohol or drug problems. They found 73% received pressure from personal relationships (e.g., friends and family), institutions (e.g., criminal justice and social welfare), or both. Polcin and Weisner (1999) studied 927 individuals entering alcohol treatment programs and found coercion to enter treatment was common. Coercion was defined as receiving a threat of serious consequences if the individual did not seek treatment. Examples of consequences included losing an important relationship such as a spouse, losing a job, loss of housing, serious medical problems, serious emotional problems, and legal consequences. Over 40% of the sample received coercion and the most common source was from family (24%).

Overall, studies suggest a wide variety of individuals entering treatment in the U.S. receive pressure, although some groups may be more susceptible. For example, Polcin and Weisner (1999) found individuals with more severe psychiatric and family problems were more likely to receive pressure. Polcin and Beattie (2007) found differences between pressure from institutions and interpersonal relationships. Receiving pressure from institutions was predicted by being unemployed or working part-time and having more severe legal problems. Relationship pressure was predicted by severity of alcohol problems.

Receipt of pressure appears to be associated with treatment entry across the course of addiction and recovery. Up to 40% of individuals entering treatment have at least one prior treatment episode (Satre, Mertens, Areán, & Weisner, 2004) and pressure appears to be common among these reentering clients as well as those entering treatment for the first time. To the best of our knowledge, none of the studies on pressure and treatment entry have shown that receipt of pressure prior to treatment is more or less common among first, second, or subsequent episodes.

Recent studies have also examined receipt of pressure to change drinking using international samples. For example, using data from the GENACIS project (Wilsnack, Wilsnack, Kristjanson, Vogeltanz-Holm, & Gmel, 2009) Olafsdottir and colleagues (Ólafsdóttir, Raitasalo, Greenfield, & Allamani, 2009) looked at pressure to change drinking or enter treatment in 18 countries using general population samples. Although receipt of pressure about one’s drinking varied widely among countries, larger proportions of men reported receipt of pressure across all countries studied and spouse was consistently the most common source. Countries where receipt of pressure was most common included Sri Lanka and Uganda, where 22% of men surveyed reporting receiving pressure. Countries that were lower on receipt of pressure included Spain (1% of men reporting confrontation) and Sweden (3%). Overall, there appeared to be a relationship between a country’s aggregate level of drinking and social pressures to control drinking. Higher levels of aggregate drinking appeared to be associated with increased pressure.

It should be noted that there are important cultural considerations that must be noted when examining pressure. For example, some countries in the GENACIS study (e.g., Uganda) have very limited availability of treatment and even mutual help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Pressure to attend treatment in those cases is often a moot point. However, in European countries treatment is typically available and pressure is common. For example, in a study of 1,865 individuals entering treatment in Sweden, Storbjork (2006) found 75% indicated receiving informal social pressure (e.g., family and friends) about their drinking and 23% reported receiving legal pressure.

Rather than looking at treatment entry in dichotomous terms (pressure versus not) a few studies have examined treatment seeking by asking individuals about a wider array of reasons for entering treatment. For example, in a sample of 167 problem drinkers Tucker et al. (2004) identified three factors as reasons for entering treatment: 1) alcohol-related problems and related social pressure to seek treatment, 2) job-related problems and pressure from work, and 3) a factor combining religious reasons and legal inducements. Using a small sample of 26 young adults entering alcohol treatment Wells et al (2007) reported that recognition of problems related to drinking and a need for assistance to address them were the main reasons help was sought. However, recognition of a need for treatment usually occurred together with social pressures to seek help.

Pressure may be particularly important to facilitate treatment entry because even when problem drinkers know they need help and recognize drinking-related problems they often do not seek assistance. SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Office of Applied Studies, 2009) studied individuals with alcohol problems who acknowledged they needed treatment and found 42.0% of these individuals did not seek help because they were not ready to stop drinking.

Improving utilization of treatment is important because a variety of studies have shown that when individuals seek treatment they derive substantial benefit. For example, Dawson et al (2006) used the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) to study the effect of help seeking on outcomes among 4,422 individuals dependent on alcohol. They reported that help seeking significantly increased the likelihood of abstinent and non-abstinent recovery. The definition of recovery considered alcohol consumption as well as DSMV IV criteria assessing alcohol-related consequences on social functioning, work, health and other areas. Weisner, Matzger and Kaskutas (2003) compared individuals with alcohol problems who received treatment with those in the general population who did not. They reported that those receiving treatment were 14 times more likely to be abstinent at one-year follow up. Individuals who were not completely abstinent were less likely to report alcohol-related problems such as drunk-driving arrests, public drunkenness, other alcohol-related arrests, traffic accidents, confrontations about an alcohol-related health problem from a medical practitioner, alcohol-related family problems and alcohol-related work problems. Although most studies examining alcohol-related outcomes have looked at the beneficial effects resulting from treatment, others have examined the benefits of engagement in mutual help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. For example, Moos and Moos (2006) studied 461 treated and untreated individuals with alcohol dependence over 16 years. For both groups, those who participated in Alcoholics Anonymous for longer periods of time were more likely to sustain remission.

One of the limitations of current studies on pressure and treatment seeking is they typically do not examine pressure within the context of other potential reasons. For example, it is unclear to what extent individuals who receive pressure and who seek treatment do so primarily because of the pressure they received. Other reasons for seeking treatment could be equally or even more important, such as improving relationship, work, or health problems.

Another limitation of some current studies is that they have used relatively small numbers of treatment seekers and have failed to examine how reasons for seeking help change over time. Analyses depicting how reasons vary over time could have implications for improving treatment utilization. For example, it could be that characteristics of different time periods call for different strategies to increase help seeking. On the other hand, if reasons for seeking help are consistent over time, adapting strategies to increase receipt of treatment based on the characteristics of different time periods may not be warranted.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine primary and aggregate reasons for seeking treatment. We were particularly interested in examining the extent to which pressure was identified as a primary reason for seeking treatment and as part of a constellation of reasons, such as a desire to improve relationships, health, or finances. We hypothesized that sources of pressure would be associated with related reasons. For example, we expected pressure from police would be associated with legal problems/feeling forced as the primary reason for entering treatment. Similarly, pressure from family, friends and spouse would be associated with entering treatment as a desire to improve relationships with family and friends. We expected pressure from a physician to be associated with entering treatment to improve health.

Methods

Survey Data

Data were taken from National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) conducted by researchers at the Alcohol Research Group. NAS surveys use cross sectional designs at approximately 5-year intervals dating back to 1979, although data on reasons for treatment seeking only date back to 1995. The primary purpose of NAS surveys has been to document trends in alcohol consumption among U.S. residents age 18 and older. NAS surveys have also tracked related variables, such as the social contexts of drinking and the prevalence of various types of alcohol-related harm.

The four administrations of NAS Surveys used for this analysis include N9, N10, N11 and N12. The surveys have a high degree of comparability between them, particularly in highly similar item content. One difference was that N9 used a multi-stage clustered sample, which included in-person interviews, while N10 – N12 used random digit dial (RDD) telephone survey methods. The switch from face-to-face interviews with stratified cluster sampling in N9 to RDD telephone interviews in N10, N11 and N12 was accompanied by extensive methodological work comparing these two modes during the same time period. We found prevalence estimates of major drinking behaviors to be substantively comparable, in spite of the lower response rates for the telephone interviews (Greenfield, Midanik, & Rogers, 2000; Midanik & Greenfield, 2003; Midanik, Hines, Greenfield, & Rogers, 1999; Midanik, Rogers, & Greenfield, 2001). All four administrations of the NAS used in this analysis over-sampled for Latino/Hispanics and African Americans. All surveys were weighted to the U.S. general population. Therefore, the over-sampling should not bias the results because they are accounted for by the weights in the analysis (Kerr, Greenfield, Bond, Ye, & Rehm, 2004).

Described below are the four data sets to be used in the study:

N9 Survey

These data were collected in 1995 (N=4,925) by the Institute for Survey Research at Temple University using a multi-stage stratified sample of 100 PSUs. African Americans and Latinos/Hispanics were over-sampled and the overall response rate was 77%.

N10 Survey

The data were collected in 2000 (N=7,612) by the Institute for Survey Research using a list assisted RDD method and Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) methods. African Americans, Latino/Hispanics and low population states were over-sampled. The response rate was 58%. The lower response rate compared to previous surveys is not unusual for telephone surveys (Kerr et al., 2004). This method has the advantage of collecting data on a larger number of individuals and lower design effects compared to in-person surveys.

N11 Survey

The data were collected in 2005 (N=6,919) by Data Stat Inc. in Ann Arbor, Michigan. They again used a RDD CATI telephone survey. African Americans, Latino/Hispanics and low population states were over-sampled. The response rate was 56%.

N12 Survey

These data (N=7,969) were collected by ICF Macro in 2009 and 2010 using a CATI and RDD. A dual-frame design, using landline and cell phones, accounted for 97.5% of all US households. As in prior surveys, oversampling for black and Hispanic populations and low-population states are included in the landline sample. This survey year had a 52% response rate. The NAS data series used here has been used successfully in a number of trend and age-period-cohort analyses, which together have added assurance of the suitability of this series of highly comparable surveys for conducting trend analysis (Greenfield & Kerr, 2008; Kerr, et al., 2004; Kerr, Greenfield, Bond, Ye, & Rehm, 2009; Kerr, Greenfield, & Midanik, 2006).

NAS data have also been used successfully in previous studies of pressure that this paper expands upon. Polcin et al (2012) used NAS datasets to describe the characteristics of individuals who received pressure and Korcha et al (under review) showed that receiving pressure was associated with seeking help for alcohol problems. Although we know receiving pressure was associated with help seeking in our data, we do not know if the pressure received was the only reason individuals sought help, the primary reason, or one of many different reasons. Knowledge about the reasons individuals seek treatment has implications for facilitating motivation and treatment planning. If we know what factors brought clients to treatment we can 1) use those issues during treatment to motivate completion of treatment and 2) draw up a treatment plan that maximizes relevance to issues that are paramount to the client (i.e., reasons they sought help).

Measures

Demographic items consisted of standard characteristics such as gender, age, race, marital status, and education and were used to describe the characteristics of current drinkers who sought treatment.

Treatment Seeking was defined using two items. The first asked if participants ever received treatment for a chemical dependency or substance abuse problem for either alcohol or drugs. A second item asked if the treatment was for a drinking problem, a drug problem or both. Those who indicated a drug problem only were eliminated from the analysis. Participants were included in analyses if they indicated any help seeking for alcohol problems over their lifetime. Reasons for Seeking Treatment included a variety of questions about reasons for seeking treatment. If multiple treatment episodes were reported the respondent was asked to consider the one that was most recent. Thus, we cannot be sure about when treatment occurred. The data collection time points therefore need to be understood as snapshots of lifetime measures at a specific time points rather than comparisons of treatment episodes between 5-year intervals. Examples of reasons for seeking treatment include potential benefits: improve relationships with family and friends, solve problems at work, resolve legal problems, improve health, improve finances and improve mental well-being. Alternately, respondents could indicate they sought treatment because they “were pressured to go.” Other items asked about motivation were based on a desire to “quit drinking” or “cut down on drinking.” For this analysis we combined items into six reasons: 1) pressured to go (i.e., felt forced) or the need to clear up a legal problems, 2) improve relationships with family or friends, 3) improve mental well-being, 4) improve physical health, 5) a desire to quit or cut down on drinking, and 6) a need to resolve work or financial problems. Participants were asked to indicate whether each reason led them to seek treatment with a yes or no response. Another item was a forced choice that required respondents to indicate the most important reason for seeking treatment.

Lifetime pressure consisted of six items measuring pressure from spouse/someone lived with, family, friends, physicians, work, and police. Respondents were asked if they received pressure from each of these sources at any point in their lives. Pressure was coded as a dichotomous variable indicating receipt of pressure versus not. Four items directly asked whether the respondent experienced pressure to change drinking from four different sources. The wording of each item was geared to how we believed pressure from each source may have typically transpired:

My spouse or someone I lived with got angry about my drinking or the way I behaved while drinking.

A physician suggested that I cut down on drinking.

People at work indicated I should cut down on drinking.

A police officer questioned or warned me about my drinking.

Two additional sources, family and friends, asked whether “other people might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank.” Participants were asked specifically whether a variety of people ever felt that way including parents, other relatives, girlfriend or boyfriend and other friends. Parents and other relatives were combined into a “family” variable and girlfriend of boyfriend and other friend were combined into a “friend” variable. This measure of pressure and variations of it have been used at ARG for many years (e.g., Hasin, 1994; Room, 1989); Schmidt, Ye, Greenfield, & Bond, 2007; Polcin, et al., 2012; Korcha et al., under review).

Lifetime pressure could have occurred at any point in the person’s life. Therefore, the pressure at specific NAS time points must be conceptualized as a cross sectional view of a lifetime measure at that time point rather than depiction of pressure between NAS time points. However, Room et al. (1991) used this measure of pressure in earlier NAS datasets and showed that lifetime pressure differed over NAS year. Significant trends were noted in overall pressure and pressure from different sources.

Analysis Plan

All analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Software v.11 (Stata Corp., 2009). Reported sample sizes are unweighted, while percentages, chi square values, and odds ratios are weighted. The weighted data were used to control survey design effects and they resulted in slightly different values than what one would have found using unweighted data. Multivariate logistic regression models report relationships between source of pressure and reasons for seeking treatment.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

Across all four surveys there were 476 individuals who indicated they sought treatment for an alcohol problem. Descriptive characteristics can be found in Table 1. A majority were male (72.7%), age 30 – 49 (57.6%), married or cohabitating (58.8%), and white (78.5%). In terms of education, over half (54.9%) had a high school diploma or less.

Table 1.

Demographics, sources of pressure and reasons for seeking help

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Sought help (N=476) | ||

|

| ||

| n | Weighted Percent | |

|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| NAS survey year | ||

| 1995 (N9) | 93 | 19.6 |

| 2000 (N10) | 136 | 28.6 |

| 2005 (N11) | 89 | 16.5 |

| 2010 (N12) | 158 | 35.4 |

| Gender | ||

| men | 331 | 72.7 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 81 | 22.7 |

| 30–49 | 256 | 57.6 |

| 50+ | 136 | 19.8 |

| Education | ||

| LT high school | 79 | 16.7 |

| HS graduate | 168 | 38.2 |

| some college | 139 | 28.5 |

| college graduate | 88 | 16.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| married/cohabitating | 212 | 58.8 |

| sep/wid/div | 134 | 18.6 |

| never married | 115 | 22.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 296 | 78.5 |

| Black | 96 | 10.0 |

| hispanic | 63 | 5.7 |

| Other | 21 | 5.8 |

| Pressure to quit or change drinking behavior (lifetime) | ||

| Sources: | ||

| Spouse/Intimate | 332 | 67.2 |

| Family members | 343 | 74.7 |

| Friends | 286 | 57.5 |

| Doctor | 223 | 44.1 |

| Work | 158 | 29.6 |

| Police | 268 | 58.6 |

| Any of the 6 sources of pressure above | 434 | 90.3 |

| Reasons for seeking help | ||

| Legal/felt forced | 344 | 74.0 |

| Improve relationships with family & friends | 295 | 58.6 |

| Improve well-being | 352 | 68.5 |

| Improve physical health | 298 | 58.6 |

| To quit or cut down on drinking | 395 | 80.8 |

| Resolve problems with work/finances | 280 | 56.6 |

| Primary reason for seeking help | ||

| Legal/felt forced | 130 | 33.8 |

| Improve relationships with family & friends | 117 | 25.2 |

| Improve well-being | 77 | 13.6 |

| Improve physical health | 67 | 14.9 |

| To quit or cut down on drinking | 50 | 8.6 |

| Resolve problems with work/finances | 18 | 4.0 |

| Number of reasons for seeking help | ||

| 1–2 | 96 | 24.2 |

| 3–4 | 140 | 30.1 |

| 5–6 | 240 | 45.7 |

Over 90% of the sample indicated they received some type of pressure to quit or change their drinking. The most common source of pressure was family (74.7%), followed by spouse (67.2%) and police (58.6%). However, pressure was relatively common among all sources, including the workplace (29.6%).

Seventy-four percent of the participants indicated that a legal problems/feeling forced was a reason for seeking treatment. However, pressure as a reason for seeking treatment occurred within the context of a variety of additional reasons. For example, 80.8% indicated a desire to quit drinking or cut down was a reason for entering treatment and 68.5% indicated a desire to improve well-being as a reason. Overall, over 75% of the sample indicated three or more reasons for seeking treatment (Table 1).

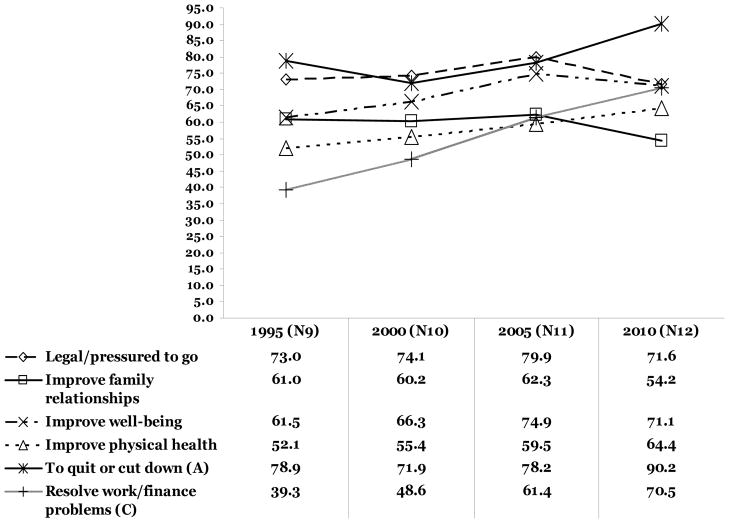

Reasons for Seeking Treatment over Time

Figure 1 shows how reasons for seeking treatment varied over survey time periods. Comparing these composite lifetime measures at different NAS time points yielded several interesting findings. With the exception of work, over half the sample endorsed every reason at every time point. Most reasons were relatively flat over NAS time points and did not have significant differences. However, exceptions included work and a desire to quit or cut down, both of which showed large increases. Work increased in a fairly linear manner over the four time points, whereas a desire to quit/cut down had a particularly large increase between 2005 (78.2%) and 2010 (90.2%).

Figure 1.

All reasons for seeking help by NAS year (weighted percents) &.

&Categories are not mutually exclusive.

(A) p<.05; Chi2 comparison across NAS years

(C) p<.001; Chi2 comparison across NAS years

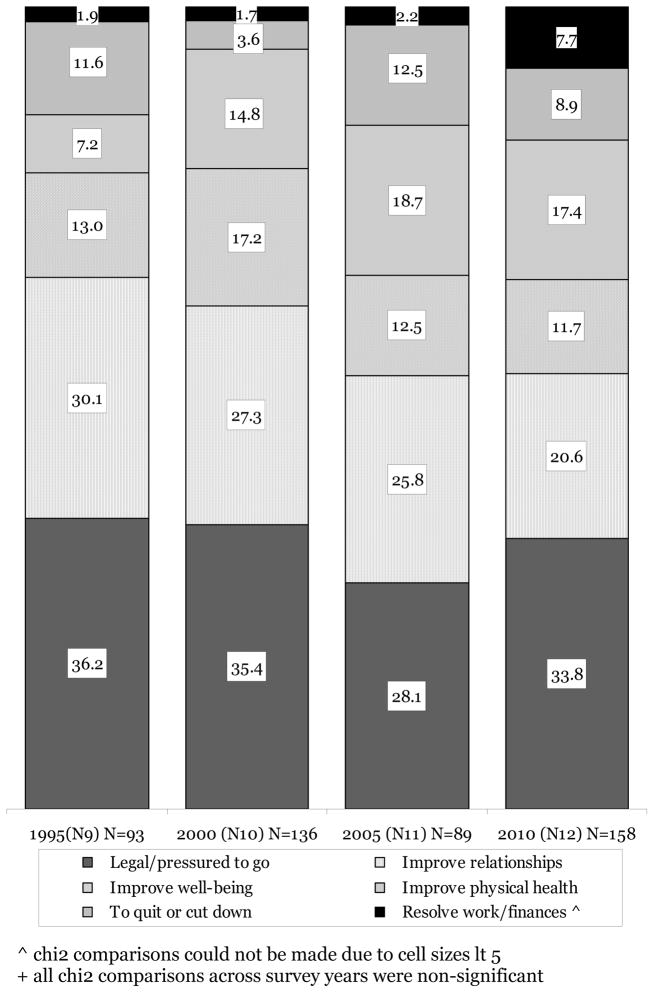

Results differed when we asked respondents to indicate their primary reason for seeking treatment. Figure 2 shows that legal problems/felt forced as a primary reason for seeking treatment ranged from 28.1% in 2005 to 36.2% in 1995. The second most common reason was to improve family relationships, which ranged from 20.6% in 2010 to 30.1% in 1995. To compare whether each of the primary reasons for seeking treatment varied over time we conducted chi square analyses and found none to be significant.

Figure 2.

Primary reason for seeking help by NAS year (weighted percents).

^ chi2 comparisons could not be made due to cell sizes lt 5

+ all chi2 comparisons across survey years were non-significant

Sources of Lifetime Pressure and Reasons for Seeking Treatment

One of our aims was to document how reasons to seek treatment were associated with sources of pressure. Table 2 shows the proportion of individuals who received pressure at some point in their lives from different sources by primary reasons to seek treatment. These analyses depict data from all NAS time points combined.

Table 2.

Percent that experienced pressure from different sources by each primary reason for seeking treatment (weighted percents).

| REASON: | PRESSURE SOURCE | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| SPOUSE/INTIMATE | FAMILY | FRIENDS | DOCTOR | WORK | POLICE | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| N | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Legal/felt forced | 130 | 77 | 50.9 | 83 | 66.9 | 64 | 39.5 | 35 | 21.3 | 23 | 9.8 | 80 | 62.2 |

| Improve relationships | 117 | 97 | 81.1 | 98 | 86.1 | 81 | 70.6 | 65 | 52.1 | 46 | 40.5 | 66 | 59.0 |

| Improve well-being | 77 | 47 | 55.4 | 53 | 63.6 | 41 | 53.0 | 37 | 48.5 | 27 | 30.3 | 37 | 55.4 |

| Improve physical health | 67 | 48 | 81.9 | 53 | 86.1 | 45 | 76.4 | 46 | 73.6 | 32 | 47.2 | 37 | 60.6 |

| To quit or cut down | 50 | 36 | 73.8 | 29 | 62.5 | 34 | 70.0 | 22 | 43.9 | 18 | 31.7 | 31 | 53.7 |

| Resolve work/finances | 18 | 13 | 84.2 | 15 | 95.0 | 10 | 52.6 | 11 | 68.4 | 6 | 47.4 | 8 | 42.1 |

Several prominent associations between sources of pressure and reasons for seeking treatment can be noted: 1) Pressure from spouse and family were the most common sources of pressure across reasons. Every reason had over half of the participants reporting receipt of pressure from spouse and family at some point in their lives. Several of the reasons for seeking treatment (e.g., improve relationships, improve physical health and resolve work problems) had over 80% reporting pressure from spouse or family. 2) Interpersonal pressures (spouse, family and friends) were more common when the primary reason for seeking treatment was to improve relationships (70.6% – 86.1%) and less common when the primary reason was legal/felt forced (39.5% – 66.9%). 3) Relatively few of those who reported pressure from doctors and work identified pressure as the primary reason they sought help (21.3% for doctor and 9.8% for work). 4) When pressure was reported from doctors, “improve physical health” was a more common reason to seek help than other reasons (73.6%). 5) When respondents received pressure from work, “resolve work/finances” was a more common primary reason for seeking treatment (47.4%). 6) When pressure was received from police, “legal/felt forced” was a more common primary reason to enter treatment than other reasons (62.2%).

We used logistic regression analyses to assess how receipt of pressure from the six different sources predicted legal problems/felt forced as a primary reason for seeking treatment (see Table 3). To ensure sufficient statistical power for this analysis we combined all NAS surveys into one model. The comparison group for each source of pressure was no pressure from that source. The model controlled for age, sex, and ethnicity. Individuals who reported receiving pressure from physicians were 60% less likely than those who did not receive such pressure to identify legal problems/felt forced as the primary reason for seeking treatment. Similarly, pressure from work was associated with lower odds of identifying legal problems/felt forced as a primary reason (OR=0.2, CI=0.1 – 0.6). In contrast, we found those who reported pressure from police were over twice as likely as those who did not report pressure from police to report legal problem/pressure as the primary reason for help seeking. Demographic correlates of legal problems/felt forced included being male and a non-significant trend toward younger age groups.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models predicting legal pressure/felt forced as primary reasons for help seeking (weighted models).

| Demographics: | Legal/felt forced to go to treatment

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Confidence Intervals | ||||

| OR | lower | upper | P | |

|

|

||||

| Gender (ref=women) | ||||

| Men | 2.9 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 0.01 |

| Age (ref=50+) | ||||

| 18–29 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 6.4 | 0.07 |

| 30–49 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity (ref=non-white) | ||||

| White | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.37 |

|

| ||||

| Pressure source: (ref=no pressure) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Spouse/Intimate | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.14 |

| Family | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0.80 |

| Friends | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.19 |

| Doctor | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.00 |

| Work | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.00 |

| Police | 2.2 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 0.02 |

Discussion

Study findings support previous research (e.g., Tucker et al., 2004; Wells, et al., 2007) showing that individuals typically seek treatment for alcohol problems for multiple reasons. When pressure is identified as a reason, it is usually in addition to other reasons rather than the sole motivation. For example, our results show that when individuals identify pressure as a reason to go to treatment they often also cite a desire to quit or cut down drinking as a reason. These findings are consistent with results reported by Storbjork (2006), who found that interpersonal pressure was a common precipitant to treatment entry among a Swedish sample. Although 75% of the sample reported receiving interpersonal pressure, 81% indicated seeking treatment was their own idea. This suggests there may be personal motivations about self-improvement in addition to reacting to pressure. Twenty-three percent of the sample reported legal pressure to enter treatment and receipt of legal pressure was associated with lower perception of self-choice.

Our study adds to previous research on treatment entry in a number of ways. First, it uses a much broader array of reasons for entering treatment, including improvements drinkers wish to make on issues such as health, well-being, work, and interpersonal problems. Second, the study is one of very few that examines the interplay of primary and aggregate reasons for entering treatment among a large U.S. sample. Finally, the study examines how measures of lifetime pressure from various sources are associated with reasons for seeking help. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the extent to which pressure to change drinking is indicated as a reason for entering treatment.

Each data collection time point of the NAS surveys reflects a snapshot of lifetime pressure and help seeking in the U.S. Our results therefore do not constitute 5-year measures of pressure and help seeking between NAS survey administrations. Using these methods, we found reasons for entering treatment to be fairly consistent over the past 15 years. Primary reasons for entering treatment showed no differences. When reasons were aggregated and participants included all reasons (primary and others), four of the six reasons showed no differences. Exceptions included resolving work/financial problems, which showed a linear increase when participants were asked to indicate all reasons, and a desire to quit or cut down, which increased primarily between 2005 and 2010.

The increase in resolving work problems as a reason to seek treatment needs to be understood within the context of work being a relatively less common reason compared to others. Among aggregate and primary reasons, work was the least mentioned as a reason to seek treatment. The increase noted over the course of NAS years could be due to several issues. One is the worsening economy and tighter job market over the past 15 years. It is possible that there is less tolerance of alcohol-related work problems and they therefore have become more prevalent as a reason to seek help. Another possible reason could be due to increased surveillance of drinking problems in the workplace in recent years and the use of Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) to address alcohol and drug problems (Trice & Beyer, 1984). Jacobson and Attridge (2010) reviewed trends in the prevalence and use of EAPs over the past several decades and documented a consistent increase since the 1980’s. They noted that currently the majority of large U.S. employers now provide EAP benefits to employees and their family members and more than 75% of employees in state and local government have access to EAP services. Individuals with alcohol and drug problems are often mandated to attend EAP services and must comply with treatment recommendations to continue employment.

When respondents indicated their primary reason for seeking help, legal problems/felt forced was the most often cited reason. However, those who indicated legal problems/felt forced did not have particularly high percentages reporting receipt of pressure. Improving relationships, improving health, and resolving work/financial problems as reasons for entering treatment all had larger proportions reporting receipt of pressure than the legal problems/felt forced reason.

We had expected that some sources of pressure would be related to reasons for seeking treatment. For example, we thought that pressure from physicians would be related to seeking treatment because of a desire to improve health. Pressure from family and friends would be related to seeking treatment because of a desire to improve relationships. However, our descriptive data in Table 2 showed mixed findings in this regard. For example, while pressure from spouse and family was high for those indicating they sought treatment to improve relationships with family and friends, these sources of pressure were also high among other reasons. Proportions reporting pressure from spouse and family among those seeking treatment to improve relationships were similar to those seeking treatment to improve health and resolve work/finances. Some support for our hypotheses can be found in the proportion reporting pressure from physicians among those seeking treatment to improve health. While pressure from physicians was evident among all reasons, the proportion was higher for those seeking treatment to improve health. A similar finding can be seen for those seeking treatment to resolve work/financial problems. Proportions reporting pressure from work were higher than they were for most other reasons.

Evident in the descriptive data in Table 2 and in our logistic regression model was the finding that pressure from police was associated with a desire to clear up a legal problem/felt forced as a reason to seek help. This finding was consistent with our hypothesis. Also consistent with our hypotheses were findings indicating that individuals who received lifetime pressure from physicians and work were less likely to report legal concerns/felt forced as a primary reason for entering treatment. For individuals seeking treatment for health or work reasons, seeking treatment may not be the result of pressure itself, but the potential harm that could result if action is not taken (i.e., worsening health problems or loss of a job). More importantly, work and health problems may be particularly salient factors in eliciting pressure from others who are concerned about them, such as a spouse, family, and friends. Results in Table 2 show these sources of pressure had large proportions indicating improving health and resolving work/finances as reasons for seeking help. Unfortunately, we did not have a sufficiently large number of individuals indicating these as primary reasons to assess them using multivariate models.

Implications

Study findings make clear that external pressure is an important reason why individuals seek treatment. Thus, public policies should support the use pressure to facilitate help seeking. However, study findings also show reasons for seeking treatment are complex and the common method of examining treatment entry by comparing clients who are criminal justice mandated versus voluntary is insufficient. Our results suggest that pressure (operationalized as legal problems or feeling forced) as a reason to enter treatment occurs within the context of a variety of other reasons and it is relatively rare that pressure is the sole reason for seeking help. Practitioners working with clients should therefore explore a wide variety of potential reasons they are seeking help, even when clients are going to treatment because of a form of duress. These would include reasons that were common in our data, such as a desire to improve relationships, health or overall well-being. Knowledge about the variety of reasons individuals seek treatment can be used to mobilize motivation to complete it. In addition, reasons for seeking treatment can inform what areas to address in developing the client’s treatment plan. Our results are highly inconsistent with a somewhat popular notion that those with a legal mandate to attend treatment are unmotivated or only motivated to complete the legal mandate. Our findings suggest most clients entering treatment recognize the need to work on problems affected by their drinking, such as improving relationships, health and well-being.

Future studies of how pressure affects treatment-seeking might examine different pathways. Pressure itself could be one source of motivation to seek help, but pressure might also lead individuals to reflect on problems and concerns that then also become reasons. Our understanding of the mechanisms of how pressure works might be improved by studying how different types of problems lead to elicitation of pressure from different sources (e.g., family, friends, legal system), and then how these pressures influence recognition of problems that ultimately become reasons for seeking help. Such an understanding could provide guidelines to practitioners to help them facilitate types of pressures associated with problem recognition and treatment entry. Results from this type of investigation might also assist criminal justice and public health administrators to develop institutional pressures that facilitate recognition of problems and treatment entry.

Pathways between different sources of pressure and reasons for seeking might vary under different circumstances. Thus, there may be a variety of influences on these associations that were not measured here. Mediating and moderating factors might include drinking severity, alcohol-related problems, or a variety of characteristics of persons applying as well as receiving pressure.

Limitations

There are some limitations in our study that are important to note. First, all data are self-report measures. As with all self-reports, the data are subject to distortions and errors in recall. Second, our measures of receiving pressure and seeking treatment are lifetime measures. It is therefore not possible to ensure the time sequencing of pressure and treatment seeking. For example, it is possible that in some instances pressure followed rather than preceded treatment seeking. However, Hasin (1994) has argued that associations between pressure and treatment are unlikely to involve pressure after treatment. Regardless of one’s views about the helpfulness of pressure, there is consensus in the field that pressure before treatment is extremely common (Polcin &Weisner, 1999). For a participant to have the reverse sequence (i.e., treatment and then pressure), the sequencing of events would have to proceed as follows: 1) treatment entry with no pressure, 2) pressure to reduce drinking after treatment, and 3) no subsequent treatment despite the pressure.

The lifetime measure of pressure also presents the concern that pressure might have occurred at a time point distant to treatment entry and the validity of the associations found are therefore questionable. However, it would seem that more distal time points between receipt of pressure and treatment entry would weaken associations but not necessarily change the direction of the association. Large studies of problem drinkers conducted longitudinally could specify the proximity, strength of association and sequencing of pressure and treatment seeking.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NIAAA grants R21AA018174 and P50 AA005595

References

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Estimating the effect of help-seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2006;101(6):824–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Kerr WC. Alcohol measurement methodology in epidemiology: recent advances and opportunities. Addiction. 2008;103(7):1082–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. Effects of telephone versus face-to-face interview modes on reports of alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2000;95(2):227–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95227714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Treatment/self-help for alcohol-related problems: relationship to social pressure and alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(6):660–666. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JM, Attridge M. Employee assistance programs (EAPs): An allied profession for work/life. In: Sweet S, Casey J, editors. Work and family encyclopedia. Chestnut Hill, MA: Sloan Work and Family Research Network; 2010. Available from http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/encyclopedia_entry.php?id=17296&area=All. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age, period and cohort influences on beer, wine and spirits consumption trends in the US National Surveys. Addiction. 2004;99(9):1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modeling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Midanik LT. How many drinks does it take you to feel drunk? Trends and predictors for subjective drunkenness. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1428–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT. What are the evidence-based administrative practices? Systems issues that impede delivery of effective treatment. Paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Treatment of Addictive Behaviors; Santa Fe, NM. 2006. Jan-Feb. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Hines AM, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Face-to-face versus telephone interviews: using cognitive methods to assess alcohol survey questions. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1999;26:673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Rogers JD, Greenfield TK. Mode differences in reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. In: Cynamon ML, Kulka RA, editors. Seventh Conference on Health Survey Research Methods [DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 01-1013] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Treated and untreated individuals with alcohol use disorders: rates and predictors of remission and relapse. International Journal of Clinical Health Psychology. 2006;6(3):513–526. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir H, Raitasalo K, Greenfield TK, Allamani A. Concern about family members’ drinking and cultural consistency: a multi-country GENACIS study. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2009;36(1–2):59–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleski J, Mota N, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Perceived need for care, help seeking, and perceived barriers to care for alcohol use disorders in a national sample. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(12):1223–1231. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Beattie M. Relationship and institutional pressure to enter treatment: differences by demographics, problem severity, and motivation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):428–436. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Greenfield TK, Kerr WC, Bond JC. Twenty-one year trends and correlates of pressure to change drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(4):705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Weisner C. Factors associated with coercion in entering treatment for alcohol problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;54(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R. The U.S. general population’s experiences of responding to alcohol problems. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(11):1291–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Greenfield TK, Weisner C. People who might have liked you to drink less: changing responses to drinking by U.S. family members and friends, 1979–1990. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1991;18(4):573–595. [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Mertens JR, Areán PA, Weisner C. Five-year alcohol and drug treatment outcomes of older adults versus middle-aged and younger adults in a managed care program. Addiction. 2004;99(10):1286–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L, Weisner C. Developments in alcoholism treatment: a ten year review. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 11. New York: Plenum; 1993. pp. 369–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Storbjork J. The interplay between perceived self-choice and reported informal, formal, and legal pressures in treatment entry. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2006;33(4):611–644. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH Report: Alcohol Treatment: Need, utilization, and barriers. Rockville, MD: 2009. [accessed 08/02/2010]. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/AlcTX/AlcTX.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Trice H, Beyer J. Work-related outcomes of the constructive-confrontation strategy in a job-based alcoholism program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1984;45(5):393–404. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. A factor analytic study of influences on patterns of help-seeking among treated and untreated alcohol dependent persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Matzger H, Kaskutas LA. How important is treatment? One-year outcomes of treated and untreated alcohol-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2003;98(7):901–911. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JE, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. Reasons why young adults do or do not seek halp for alcohol problems. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(12):1005–1012. doi: 10.1080/00048670701691218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]