Abstract

Background

Health, safety, and well-being (HSW) at work represent important values in themselves. It seems, however, that other values can contribute to HSW. This is to some extent reflected in the scientific literature in the attention paid to values like trust or justice. However, an overview of what values are important for HSW was not available. Our central research question was: what organizational values are supportive of health, safety, and well-being at work?

Methods

The literature was explored via the snowball approach to identify values and value-laden factors that support HSW. Twenty-nine factors were identified as relevant, including synonyms. In the next step, these were clustered around seven core values. Finally, these core values were structured into three main clusters.

Results

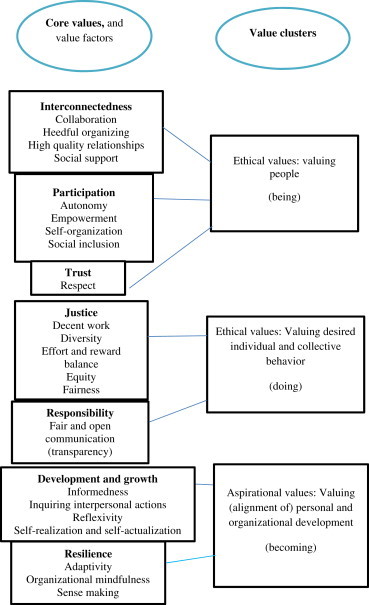

The first value cluster is characterized by a positive attitude toward people and their “being”; it comprises the core values of interconnectedness, participation, and trust. The second value cluster is relevant for the organizational and individual “doing”, for actions planned or undertaken, and comprises justice and responsibility. The third value cluster is relevant for “becoming” and is characterized by the alignment of personal and organizational development; it comprises the values of growth and resilience.

Conclusion

The three clusters of core values identified can be regarded as “basic value assumptions” that underlie both organizational culture and prevention culture. The core values identified form a natural and perhaps necessary aspect of a prevention culture, complementary to the focus on rational and informed behavior when dealing with HSW risks.

Keywords: occupational health, organizational culture, occupational safety, social responsibility, social values

1. Introduction

Health, safety, and well-being at work (HSW) represent important values in themselves. It seems, however, that other values can positively or negatively contribute to HSW. This is to some extent reflected in the scientific literature in the attention paid to values like trust or justice. However, an overview of what values are important for HSW was not available. Our central research question was: what organizational values are supportive of health, safety, and well-being at work?

As a research team we represent different research traditions, e.g., health promotion, health and safety management, and safety culture. We were surprised about the differences in theories and practices between occupational health management and occupational safety management. In the safety literature, there is much interest in “safety culture” (e.g., [1–4]), whereas there are only a few publications on the relevance of organizational culture for occupational health or well-being at work; with some notable exceptions [5,6]. Recently, there has been great interest in the concept of “prevention culture”, especially from Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) policy makers [7,8].a We felt health and safety management and culture are most likely to be two sides of the same coin and must have more in common than is reflected in the dominant, separated research traditions.

We were aware that in the safety culture literature, the values “trust” and “justice” are addressed [1]. Trust is also addressed in the literature on health or psychosocial health [9–13], and is a major issue for well-being at work, e.g., as measured by the benchmark system of “great place to work” [14]. However, we were not aware of any publication wherein trust was said to be relevant for the combination of HSW. We were also prompted by the increasingly close relationship of health and safety management and corporate social responsibility (CSR; see, e.g., [15,16]). CSR includes a “business ethics” dimension—implying attention for the social values of the organizations—and we were interested to know what that could mean for HSW. Another observation was that many organizations nowadays have a set of core values, usually defined by top management and communicated externally through the company website. Finally, we had in mind the paper of Zwetsloot [17], stating that if we want to achieve excellence in health and safety management, as well as environmental or quality management, it is essential to have a combination of the “rationalities of prevention” as organized through OSH management systems, which are essential for “doing things right”, with value management, which is important for “doing the right things.” That can be easily stated, but what would that value management mean? And what values are then relevant?

1.1. Relevant concepts and theories

1.1.1. Values

According to the Oxford dictionary [18], values are “the principles or standards of behavior; one’s judgment of what is important in life.” According to the glossary terms of the excellence model of the European Foundation for Quality Management [19], values are “operating philosophies or principles that guide an organization’s internal conduct as well as its relationship with the external world. Values provide guidance for people on what is good or desirable and what is not. They exert major influence on the behavior of individuals and teams and serve as broad guidelines in all situations.” According to the Cambridge dictionary, a “core value is a value or belief that is more important than any other” [20].

Though intangibles, values play a role in the culture of societies, but also in organizational cultures [21–23]. Values are closely associated with social norms and regarded as a vital element of organizational culture. Senge emphasizes the importance of “shared values” for successful organizational learning [24].

By defining their corporate or core values, companies give meaning to the company existence and their value for society. When core values are taken seriously and thus are more than merely “espoused theories”, they are also important for the identity and cohesion of organizations. Core values therefore underlie the organization’s mission, vision, and strategies, but also the design and functioning of their systems, structure, style of operation, and the selection and development of staff and skills [25]; they have the potential to guide the practices and behaviors of managers, supervisors, and workers. When internalized, core values are more stable than corporate structures or management systems, especially in periods of reorganization and change.

1.1.2. Health, safety, and well-being as values in themselves

There are good reasons to say that HSW represent values in themselves. Health, safety, and well-being certainly belong to what most people “judge to be important in life”, which was the second part of the definition of a value, given above. Perhaps the value aspects of HSW are most tangible in “vision zero”, the ambition to realize workplaces free of accidents or at least serious accidents and harm. At the second OSH Strategy Conference [26], representatives from governments and several European and international institutions agreed that “Vision Zero” should be regarded as both the foundation and the objective for a culture of prevention [26]. Zwetsloot and colleagues [27] call the “zero accident vision” the only ethically sustainable long-term goal for safety management. The International Labor Organization (ILO) defined the protection of health and safety at work to be a fundamental right, related to the Declaration of Human Rights, and that was confirmed by the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in 1976 [28]. The same value aspects are associated with the concept of “decent work” [29]. According to the ILO, a key element for OSH management is promoting a “culture of prevention” within the enterprise where “the right to a safe and healthy working environment is respected and where employers and workers actively participate in securing a safe and healthy working environment” [30].

1.1.3. The relevance of values for the organizational culture

Schein [31,32] distinguished three levels of organizational culture: basic assumptions, espoused values, and artifacts; the later including aspects of behavior. The basic assumptions cannot be directly observed or perceived, but they are the core of an organizational culture. The espoused values are those that the organization and its top management proclaim to be important. The artifacts, e.g., working practices, are phenomena codetermined by the corporate culture; they can easily be observed or measured, but it is not so easy to clarify the link with the two underlying layers of the culture. The influence of the deeper layers of culture, the basic assumptions and values, on the members of the organization remains largely unconscious or even subconscious [22,31,32]. It is transferred to new members of the organization through implicit socialization processes. In his research, Schein [33,34] clearly demonstrated that for a long-lasting safety improvement, a change in the organizational culture can be needed, implying that this change cannot be limited to a change in artifacts or espoused theories, but also requires a change of the “basic assumptions”, which we assume to include internalized values.

Our assumption is that characteristics of the general organizational culture, and more specifically the presence or absence of certain values in company practices, can help or hinder the development of a prevention culture.

We understand the “culture of organizations” as a complex and ambiguous concept, comprising the values, norms, habits, opinions, attitudes, taboos, rituals, and visions of reality that have an important influence on decision making and behavior of and within organizations. This research focuses on values, and does not address other relevant aspects of organizational culture or prevention culture.

1.1.4. Values and health in the workplace

Although safety culture is a frequently researched phenomenon, this is much less the case for a culture that supports occupational health or workplace health promotion. In several health theories, the social work environment is, however, regarded as a determinant of health and is increasingly recognized as relevant for healthy or unhealthy behavior. The focus on “social work environment” is, however, mostly on the environment of the individual at risk, usually at the level of teams or departments. Several authors identified culture as an important health-influencing factor [5,6,10,35,36]. The companies participating in the Enterprise for Health network share an important basic conviction that they regularly communicate externally: “Activities resulting from a corporate culture based on partnership and participation in health promotion activities are an investment in the future of their enterprises. It ensures competitiveness in the long term by building-up and maintaining innovative human wealth” [37,38]. In the World Health Organization’s recent Healthy Workplaces model, values are included as an important prerequisite of successful health interventions at work [39] without, however, specifying these values. The European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP) emphasizes the importance of organizational culture, leadership principles, and values as vital aspects of workplace health promotion [40], again without specifying the relevant values. In the European framework for psychosocial risk management, PRIMA-EF, [41] values like trust, participation, and responsibility are mentioned as important, whereas “low social value” is mentioned as a psychosocial hazard.

1.1.5. Values and occupational safety

Safety culture is an important issue in research and company practice. As Hale and Hovden stated [2], we live nowadays in the “third age of safety”, wherein the focus is no longer only on technological (the first age) or organizational measures (the second age). In addition, the focus in safety today is mainly on culture and human behavior.

There are many different definitions of “safety culture” and the related concept of “safety climate”. Guldenmund [3] presented 18 different definitions in his review article on safety culture. An important commonality of these definitions is the awareness and perception of safety risks. Only two of these definitions refer explicitly to values [42,43], but many refer to the closely related topic of “shared beliefs”.

According to Reason [1], a characteristic of a positive safety culture is a “just culture”: an atmosphere of trust that encourages people to deliver OSH relevant information and where everybody knows what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior. Justice and reliable information, even if it is bad news, generates credibility and confidence in safety management.

1.1.6. Values and well-being at work

The values that support HSW are linked to what McGregor [44] called “the human side of the enterprise” which are obviously important for well-being at work. Weisbord [45] elaborated on McGregor [44], and emphasized the importance of “organizing and managing for dignity, meaning and community.”

A related notion stems from Beer [46] who focuses on high-performance, high-commitment organizations. Beer [46] states that “Commitment cannot be developed through logical argument”. He also concludes that “employees, who are psychologically aligned with the mission and the values of the organization, are intrinsically motivated and generate high performances” [46]. An implication would be that when HSW supporting values are shared by the organization and its members, that is likely to enhance HSW as well as work performance; an example of “good HSW is good business”.

1.2. Research objectives and questions

To summarize, in different scientific traditions, individual values are recognized as HSW-influencing factors. However, a good overview of HSW-related values is missing. The present study aims to fill this gap by identifying relevant values and clustering them into a limited set of core values supportive of HSW.

Our central research question “what organizational values are supportive of health, safety, and well-being at work?” was operationalized into the following subresearch questions: (1) What organizational values or value-laden concepts are mentioned in the literature as relevant for HSW? and (2) Can these values and value-laden concepts be logically clustered around a limited set of core values relevant for HSW?

For the purpose of addressing our research questions, there is, to our knowledge, no generally accepted theory available. Consequently, several theories and scientific traditions are potentially relevant for our research. This implies that the nature of our research was exploratory.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The literature search

The first part of the research comprised a broad literature search and review. In this effort, we were interested in “values and value-laden concepts” relevant to HSW. The search term “value” was not of much help, as it almost always refers to economic value. A systematic search in Scopus using the string <core value and occupational health and safety> revealed 11 articles from 2005 to 2009, but these papers addressed only marginally the types of values we were interested in.

Therefore, it was decided to start gathering and analyzing publications with a relatively broad scope. We started with literature we had already selected in two preceding projects on, respectively, “safety culture” [1] and the importance of social–ecological contexts in health theories (especially [47]). Publications from relevant international networks and agencies were included [15,38] as well as international policy documents and underlying reports (e.g., [28,29,39,48]). We used the snowball method for our literature search, building on the broader literatures identified. We used the search terms Health, and/or Safety, and/or Well-being, and/or OSH combined with organizational culture; we also searched for, e.g., socio-ecological models and health and/or well-being at work; and we searched in the literature on the social determinants of health. Besides the traditional snowball, whereby references are used to trace older relevant literatures, we also used Google Scholar to investigate publications that cited the relevant literatures already identified for tracing recent publications.

We selected those literatures wherein values or value-laden concepts were addressed relevant for a HSW prevention culture, organizational culture, interpersonal processes, social interactions, and the processes of socialization and collective learning in organizations, as we assumed that these factors and processes are relevant for developing and maintaining shared values. Finally, during our research, we were keen to start dialogues on the value aspects of HSW with experts at international conferences the research team members participated in, in order to identify additional relevant value factors and literatures. At a later stage of our literature search, we also included literature about practical methodologies, instruments, and tools for developing a HSW prevention culture, because several tools are based on diagnostic models with underlying dimensions, which may include values, e.g., [47,49–52]. The search was ended when further snowballing did not lead to the identification of additional value factors.

We excluded factors or concepts that have a predominantly “system” character, such as work organization or management systems, as well as factors that are primarily bound to individual workers or managers, e.g., competencies or individual characteristics. When we considered, for example, Karasek and Theorell’s [53] well-known job strain and stress theory, the factors “job demands” and “decision latitude” were excluded because these characterize “the system” rather than values of organizations. However, the factor “social support” in this theory was included because it is clearly associated with social interactions in organizations. Factors like leadership, commitment, excellence, etc., were excluded as well. We acknowledged that the various leadership styles are likely to be implicitly associated with various sets of values. This is certainly an interesting research topic, but our focus was on values that support HSW, and not on the value implications of various leadership styles.

It was not our intention to list as many as possible references on certain value factors, e.g., on social support or justice. Instead, we aimed to identify relevant values based on significant publications. We were not able to perform an exhaustive literature search on each individual core value, and an attempt to present a complete overview of their meaning was beyond the scope of this research and publication.

2.2. The clustering process

As a result of the literature research, 29 values or value-laden concepts were identified, but it was obvious that several were synonyms, were overlapping, or were somehow related. There was clearly a need to make clusters of closely related value factors. This was mainly done through “content analysis”: similar concepts, for example, fairness and justice, were clustered. This was done by the researchers jointly in dialogue. Only in a few cases the clustering process was not straightforward, e.g., stakeholder involvement is clearly related to corporate social responsibility, but also related to participation. For reasons of clarity, every value factor was attributed only to the cluster it was judged most relevant for.

To identify a core value for each cluster, the question arose, “what values are more central than other values or value-laden factors?” Like organizational culture in Schein’s [31] model, our understanding was that values are multilayered; some value factors are “essential values”; comparable to Schein’s “basic assumptions”, these are potentially relevant for the identity of organizations, and we selected them as the core values. Other factors seemed to be “expressions of” such deeper values, and may have more in common with what Schein [31] called “espoused values” or “artifacts”. For example, interconnectedness was selected as a core value, whereas “social support” was regarded as an expression thereof.

2.3. Validation

Both the clustering of value factors and the selection of the core values for each cluster were not done in academic isolation. Two workshops were held with stakeholders, regarded as experts. Reports were made of those meetings; the reports were fed back to the participants to verify the conclusions.

In the first stakeholder meeting company representatives, independent HSW experts and business consultants participated (n = 14). They were selected because they were known in The Netherlands as strategic thinkers, pursuing simultaneously excellence in HSW and in business performance and/or corporate social responsibility. In this meeting, the idea of using corporate values to support a HSW culture was presented, analyzed, and discussed. The participants were challenged to clarify the meaning of core values of the companies they represented, or in the case of independent experts, those they knew well, for the development of a HSW prevention culture. The participants were also invited to give feedback and associations on the cultural factors identified. We invited them to cluster the cultural factors and select for each cluster one of them as the “core value”. Although the research team had initially identified six clusters, the stakeholders came up with seven clusters, the cluster around participation being the additional cluster. This prompted us to adapt our clustering accordingly.

In a second workshop with representatives from Dutch front-runner companies in HSW, who were experts/practitioners in HSW, the adjusted set of now seven HSW relevant core values and clusters was presented and discussed to make sure they had face validity for the company representatives. There were eight experts participating, one expert participated also in the first workshop. The participants also discussed the practicalities of developing core values to support HSW; these are used in the discussion section of this paper.

Finally, as the last step in our research project, we decided to categorize the seven core values identified. Again the clustering was done jointly by the research team, in dialogue. We ended up with three main categories of core values that are supportive of HSW. Because these categories are rather abstract in nature, it was not regarded as useful to organize a validating workshop with stakeholders because their expertise is primarily at the practical level.

In a related unpublished research effort, we explored theories and practices of value management by organizations. The findings thereof helped us to address the practical relevance of our research in the discussion section of this paper.

3. Results

Our literature search yielded a variety of value factors from a range of theories used in research on HSW. Table 1 gives an overview.

Table 1.

Values and value-laden factors identified as potentially relevant for health, safety, and well-being

| Value or cultural factor (alphabetical order) | Relevant for | Theory or methodology/tools | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptivity | Health | Redefining health | [54] |

| Resilience | Resilience engineering | [55] | |

| Autonomy | Well-being | Self-determination theory | [56] |

| Collaboration | Mental health | Social capital | [11,12] |

| Business excellence | |||

| Connectedness or interconnectedness | Well-being, identity | Human resource management | [57–60] |

| Decent work | Better work life | Humanization of work | [29] |

| Diversity | Equity and nondiscrimination | Human resource management | [61] |

| Effort and reward balance | Mental health at work | Effort and reward theory | [62] |

| Empowerment | Psychosocial aspects of work and health | Human resource management | [63,64] |

| Equity | Social determinants of health | Public health | [48,61,65,66] |

| Fair and open communication | Mutual understanding, acceptance, and learning | Dialogue theory, organizational learning, business ethics | [67,68] |

| Fairness | Health equity | Social determinants of health | [69] |

| Heedful organizing | Safety, resilience | High reliability organizations | [70] |

| High quality relationships | Thriving at work | Organizational studies | [59] |

| Informedness | Safety culture | Safety | [1,71] |

| Inquiring interpersonal actions | Desired organizational change | Appreciative inquiry | [50] |

| Better understanding of complex issues | Dialogue theory | [51,67] | |

| Socratic conversations | |||

| Individual and organizational learning | Theory U | [72] | |

| Meaningful conversations | World café | [52] | |

| Justice | Safety | Safety culture | [1,73] |

| Mental health | Health and well-being | [9,74] | |

| Organizational mindfulness | Safety, resilience | High reliability organizations | [70] |

| Participation | Large-scale interventions | Organizational development | [75] |

| Community approach | Health promotion | [47,64] | |

| Occupational safety and health | Health and safety policies and management | [7,76] | |

| Reflexivity | Modern legislation on risk management | Reflexive legislation | [77] |

| Resilience | Safety | Resilience engineering | [55] |

| Managing the unexpected | High reliability organizations | [70] | |

| Resilient people and organizations | Human resource management | [46] | |

| Resilience workplaces | Resilient families and groups | [78] | |

| Respect | Prevention of bullying | Dignity at work | [79] |

| (Non)discrimination | Employment | [64,80] | |

| Responsibility | Responsible care | Corporate social responsibility | [15,81] |

| Self-organization | Large-scale interventions | Organizational development | [75] |

| Organizational development | Communicative self-steering | [82] | |

| Intrinsic motivation | Self-determination theory | [56] | |

| Self-realization, self-actualization | Human needs | Hierarchy of needs | [83] |

| Basic psychological needs | Self-determination theory | [56] | |

| Sense making | Well-being | Sense making | [84] |

| Social inclusion | Well-being | Access to employment | [85] |

| Social support | Mental health | Healthy work | [53] |

| Stakeholder involvement | Sustainability | Corporate social responsibility | [86] |

| Trust | Second order learning | Theory U, organizational learning | [72] |

| Safety culture | Dimensions of safety culture | [1,73,87] | |

| Sources of health | Social determinants of health | [48] | |

| Mental health | Social capital | [11,88,89] |

3.1. Clusters of core values

In the process of clustering the value factors a core value was identified for each cluster regarded as the most essential. In one cluster, we concluded that the value factors identified, informedness, inquiring interpersonal actions, reflexivity, were either practical expressions rather than core values or were more relevant for individuals than for organizations, for example, self-realization and self-actualization. It was therefore decided to use “development and growth” as the core value for that cluster.

In the clustering on a higher level, again based on content analysis, the focus was on underlying commonalities, which were often implicit intrinsic drivers of organizational and individual behavior comparable to Schein’s [31] “basic assumptions”. In this way, we arrived at three types of core values that support HSW. The first value cluster is characterized by a positive attitude toward people, individually and collectively, and their “being”; it comprises the core values of trust, participation, and interconnectedness. The second value cluster is characterized by responsibility for actions planned or undertaken, for what people and organizations “do”. This cluster comprises the core values of responsibility and justice. The third value cluster is relevant for “becoming” and is characterized by the alignment of personal and organizational development; it comprises the values of growth and resilience.

Fig. 1 presents a framework representing the identified three value clusters, the seven core values, and the associated value factors.

Fig. 1.

A framework of core values, value factors, and value clusters that support health, safety, and well-being (HSW).

4. Discussion

We will now present some additional insights about the seven core values identified.

4.1. Interconnectedness

Human beings are “social beings” [78]. Interconnectedness is fundamental because people are not only individuals; it implies that, to a certain extent, affective involvement is important, and identity is linked with the social environment. Organizations are also social communities. Related value factors are heedful organizing, high-quality relationships, and social support.

4.2. Participation

Participation is a cornerstone in any good HSW policy and practice and part of the legislation on HSW in most countries. Tripartite organizations, such as ILO, and worker representation are fundamental to HSW policy. There is clearly a connection here with the value of a safe and healthy life for every individual, and the recognition of health and safety at work as a fundamental right [28]. Related value factors are autonomy, empowerment, self-organization, and social inclusion.

4.3. Trust

In the literature, there is a lot of evidence that trust is important for HSW; recent overviews with respect to safety are available [73,90]. However, in the literature the specific meaning attributed to the concept of trust varies, as well as references to aspects of HSW. Addressed are: mutual trust between employees and senior executives, trust in teams of coworkers and the relevance of trust for safety culture in general [91], workers’ trust in the efficacy of safety systems and in peer safety ability [92], trusted communication in managing chemical safety [93], trust between workers and management [11], trust in supervisors [94]; trust as an element of emotional social support and as a precondition for implementation of interventions [52,95] and organizational change [96]. A related value factor is respect.

There is also literature that points out that too much trust can have negative effects, especially for safety. Too much trust in, for example, the efficacy of safety systems, safety rules, and in managers’ ability to manage safety, may decrease alertness and critical reflection, which can lead to unsafe situations, especially in nonroutine situations [97,98].

4.4. Justice

In the literature on safety culture, justice is seen as an important prerequisite [1,73]. Justice, procedural as well as distributive justice, is also regarded as a determinant of mental health at work [74]. If people are not treated in a just way, they might easily become frustrated or stressed or have feelings of burnout. Related value factors are decent work, diversity, equity, effort and reward balance, and social inclusion.

4.5. Responsibility

The concept of responsibility is linked with that of “prevention culture”, partly through the closely related concept of “Corporate Social Responsibility” [15–17,99], which implies a link with business ethics. Related value factors are open communication or transparency and stakeholder involvement.

4.6. Development and growth

For organizations as well as for individuals, development and growth are important. For organizations, this implies the quest for economic growth and economies of scale, as well as innovation. For individuals, development and personal growth are important to realize their potential and for self-actualization; it can be seen as an inherent human desire [56]. Related value factors are informedness, inquiring interpersonal actions, reflexivity, self-realization, and self-actualization.

4.7. Resilience

Resilience of organizations and individuals is important for their functioning, development, and even survival under adverse conditions. It is especially relevant in complex contexts, where not all adverse conditions can be foreseen and prevented, thus implying the importance of “managing the unexpected” [70]. In human resource management literature, the importance of psychological alignment of individual and organizational values and goals is emphasized as important for organizational resilience as well as for individual well-being [46]. Related value factors are adaptivity, organizational mindfulness, and sense making.

4.8. The strategic meaning of core values for HSW

Many companies nowadays have defined their core values. In principle, these serve to define and develop their “corporate identity”. For top managers, core values are important, and they guide—in principle—their strategic decisions. The literature and the stakeholders/experts involved in our workshops suggest that the core values identified may help both to increase the strategic meaning of HSW for organizations and to strengthen top management’s commitment to HSW.

The core values identified form important cross-linkages between the often separated areas of HSW. The direct impact of core values on people, individually or collectively, is mainly described in the literature on social determinants of health and includes the experience of being valued and respected individually but also as a team and organizational member, doing “meaningful work” [100] and being inspired, motivated, and engaged through alignment of individual and organizational goals[46]. In the HSW literature, indirect impacts are described via better organizational conditions or social environment and better HSW, especially safety, management. An implication seems that the concept of “prevention culture” should not only focus on rational approaches for dealing with HSW risks, but also on the relevant social values.

The core values identified potentially have a profound impact on the organization and its members. Both direct and indirect impacts on HSW can be relevant. The impact of shared core values is addressed in the management literature extensively, often referring to the well-known “Seven S model” of the McKinsey management consultants [25]. That model suggests an impact of shared values on the structure, strategy, systems, style, skills, and staff of organizations.

The three clusters of core values are not fully independent. There is a significant relationship between justice and trust, which is described extensively in the safety literature [1,73] and by [32] in the more general literature, often in the negative: injustice leads to poor communication and distrust.

Finally, in the former century there were significant “schools of thought” inspired by the pursuit of what was then called “humanization of work”. Thereafter rational approaches dominated the thinking about health and safety. Recently, there has been renewed attention on what is now called “business ethics”, associated with corporate social responsibility as well as a broader call for human-oriented and sustainable approaches. The core values that support HSW fit well in this societal development and may perhaps even inspire the HSW community to rediscover the relevance of “humanization of work”.

4.9. The broader meaning of the HSW core values

In this research, we focused on core values and their impact on HSW. Our focus was on the organizational level. However, values and culture are also relevant on two other levels: on the macro level [21] and also on the level of occupations. Schein [101] distinguished the culture of top managers of engineers and saw these two as internationally shared values among these occupations, and workplace cultures which are often very local in nature. Both the macro and occupational culture will impact organizational culture and the adoption of core values in organizations.

The impact of values does not stop at the fence of a production plant or workplace. Values have an impact in decision-making, acting, and on the behavior of the managers and workers that have internalized them. Indeed, in the long run, companies cannot be socially responsible externally without being socially responsible internally—and vice versa [15,102]. It can therefore be no surprise that the core values identified also have a broader relevance. This is illustrated by the enormous impact of trust and distrust in financial institutions.

The three core values whereby “being” is valued, interconnectedness, participation and trust, seem also relevant for broader corporate social responsibilities, e.g., for valuing and respecting human rights, the company’s neighbors, ecosystems, indigenous people, and future generations. The values “justice” and “responsibility” are clearly key values underlying the essence of corporate social responsibility and fair business practices, and for communication with and involving stakeholders. The values relevant for aligning personal and organizational growth and development, i.e., growth and development, and resilience, are also relevant for economic development and for society as a whole. To clarify fully, these broader relationships would merit a dedicated follow-up project.

In human resource management literature, it is stated that aligning the values and goals of organizations with the goals and values of the employees is key to creating organizations that can be characterized as “High Commitment–High Performance” organizations [46]. This suggests that the core values that support HSW can also function as “organizational resources” that may complement job and personal resources in generating work engagement (compare [103]) and high performance, while fostering HSW.

4.10. Practical implications

In several companies, core values are defined at the top and are espoused as the normative framework for employees’ behavior. For the shop floor this may mean that the core values are coming from “above” and are not easily internalized as their own. According to the experience of the participants of the workshops, core values often remain vague, indefinable, and without normative and behavioral consequences for managers and personnel. In such cases, they have no effect on internal practices and little or no impact on HSW.

From an unpublished side study on the organizational practices in dealing with core values, we identified a good practice for the processes of defining and internalizing core values in organizations. In this case half of the core values were defined by top management and the other half were defined bottom-up. In the end, the set of core values was adopted explicitly by top management and workers’ representatives, and was communicated through a series of Socratic dialogue events to which all employees with a permanent contract were invited and the majority of them participated. For internal use, each core value was associated with a limited set of “keywords”, each keyword being translated into guidance for desired behavior. These behavioral guidelines were internally broadly communicated through the company media, whereby there was room for personal views and experiences. The behavioral guidelines were also input for meaningful conversations launched at dialogue events. In this way, the core values defined bottom-up had consequences for management behavior, whereas the whole set of core values received much credibility and ownership on the shop floor. Some examples on how the core values identified in this research can be made concrete and tangible by associated keywords and examples of desired behavior are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Illustrations of the translation of health, safety, and well-being (HSW) core values into desired behaviors

| Core values | Examples of associated key words | Examples of behavior, associated with the keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Interconnectedness | Social support | Good team work |

| Support by managers and coworkers | ||

| Participation | Everybody counts | Making use of the intrinsic motivation and tacit knowledge of the workers |

| Focus on people’s abilities, not on disabilities | ||

| Trust | Personal reliability | Making mistakes is acceptable as long we learn from them |

| Being consistent in actions and words | ||

| Justice | Blame-free culture | Reporting incidents is encouraged (no blame) |

| Do not shoot the messenger who points out dangerous situations | ||

| Responsibility | Future orientation | Always take long-term impacts (on HSW) into account |

| Develop ethically sustainable economic values | ||

| Development and growth | Personal development | Develop new competencies and skills |

| Learning on the job | ||

| Resilience | Anticipation | Anticipate the unexpected |

| Be prepared to adapt promptly to changing circumstances |

The adoption of the core values identified can contribute to the development of OSH management systems and other activities from employers, employees, and professionals aiming at prevention or promotion of HSW at work. It is important, however, to keep constantly in mind that shared values cannot simply be planned and deployed. It is not a matter of simply making a statement or implementing an instrument. Core values have to be “lived” by most individuals and be confirmed in social interactions to internalize them as “shared values”. That is also why business values should be combined with values of the working population. Then, in the end, the core values can become the ethical compass for all members of the organization, to the benefit of HSW, business performance, and society at large.

4.11. Methodological limitations

The nature of our research was essentially explorative. The international literature used was in the English language only, and mostly from a West-European or North-American origin, complemented by a few publications in the Dutch language. Because we started with the literature we were already familiar with, using the snowball method, we cannot guarantee that we have gained a complete overview of all values relevant for supporting HSW.

Although we followed objective and transparent procedures as much as possible, values remain to some extent ambiguous. In the clustering process, we had to deal with synonyms and overlapping value factors; we cannot exclude the possibility that other researchers would have preferred other core values or terms, for example, fairness instead of justice.

4.12. Suggestions for further research

This research explored the core values that are relevant for HSW. It opens up a range of new research perspectives. We mention here:

-

(1)

To undertake empirical research on the impact of the adoption and internalization of the core values identified on HSW.

-

(2)

To assess the relationships between the various core values, or clusters of core values identified.

-

(3)

To explore the impact of national cultures on the adoption and internalization of the core values that support HSW.

-

(4)

To explore the impact of the core values that support HSW on the wider aspects of corporate social responsibility, OHS management systems, organizational efficacy, and organizational identity.

In conclusion, in this study, 29 values and value-related factors were identified that are described in the literature as supportive to HSW. These were clustered around seven core values. These seven core values were then grouped in three value clusters.

The first value cluster is characterized by a positive attitude toward people and their “being”; it comprises the core values of interconnectedness, participation, and trust. The second value cluster is relevant for the organizational and individual “doing”, for actions planned or undertaken, and comprises justice and responsibility. The third value cluster is relevant for “becoming” and is characterized by the alignment of personal and organizational development; it comprises the values of growth and resilience.

The core values or clusters of core values identified can be regarded as “basic value assumptions” that underlie a HSW prevention culture. They form a natural and perhaps necessary aspect of a prevention culture, complementary to a focus on rational and informed behavior when dealing with HSW risks. The core values are also likely to support the development of OSH management systems and other activities aiming at the prevention or promotion of HSW. Finally, these core values have the potential to become the ethical compass for all members of the organization, to the benefit of HSW, business performance, and society at large.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare to have no financial or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence the research described.

Acknowledgments

This research project was made possible by subsidies of The Netherlands’ Ministries of Social Affairs and Employment and Health, Welfare, and Sport. We wish to thank the participants of the two workshops with stakeholders for their cooperation and especially for sharing their practical insights and notions of practical relevance. Finally, we wish to thank those participants of the 10th conference of the European Academy of Occupational Health Psychology, April 2012 in Zürich, and of the so-called “CAVI” Research Workshop, October 2012 in Copenhagen, who provided valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The ILO uses the term “preventative safety and health culture”.

References

- 1.Reason J.T. Ashgate; Aldershot (UK): 1997. Managing the risks of organisational accidents; p. 252 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale A.R., Hovden J. Management and culture: the third age of safety. In: Feyer M.A., Williamson A., editors. Occupational injury: risk, prevention and intervention. Taylor & Francis; London (UK): 1998. pp. 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guldenmund F.W. The nature of safety culture: a review of theory and research. Saf Sci. 2000;34:215–257. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guldenmund F.W. BOXPress; Oisterwijk (Netherlands): 2010. Understanding and exploring safety culture [doctoral dissertation] p. 254 p. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dollard M.F., Bakker A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J Occ Org Psy. 2010;83:579–599. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwetsloot G.I.J.M., Leka S. Corporate culture, health and well-being. In: Leka S., Houdmondt J., editors. A text book for occupational health psychology. Wiley-Blackwell; Chicester (UK): 2010. pp. 250–268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Labour Organisation (ILO) ILO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2004. Global strategy on occupational safety and health; p. 20 p. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Social Security Association (ISSA) 2012. Newsletter of the section for a culture of prevention; p. 14. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels N. Why justice is good for our health. In: Lolas F.S., Agar L.C., editors. Interfaces between bioethics and the empirical social sciences. Regional program on bio-ethics OPS/OMS. Pan American Health Organization and World Health Organisation; Chile: 2002. pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golaszevski T., Allen J., Edington D. Working together to create supportive environments in worksite health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:1–10. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-22.5.TAHP-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasle P., Moller N. From conflict to shared development: social capital in a Tayloristic environment. Econ Ind Democracy. 2007;28:401–429. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasle P., Sondergaard Kristensen T., Moller N., Gylling Olesen K. International Congress on Social Capital and Networks of Trust; Jyväslylä (Finland): October 18–20, 2007. Organisational social capital and the relations with quality of work and health – a new issue for research. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe G. Toronto University Press; Toronto (Canada): 2010. Creating healthy organizations: how vibrant workplaces inspire employees to achieve sustainable success; p. 248 p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Marrewijk M. The social dimension of organisations: recent experiences with Great Place To Work assessment practices. J Bus Ethics. 2004;55:135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zwetsloot G.I.J.M., Starren A., editors. Corporate social responsibility and safety and health at work. EU OSHA; Bilbao (Spain): 2004. p. 131 p. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain A., Leka S., Zwetsloot G.I.J.M. Corporate social responsibility and psychosocial risk management in Europe. J Bus Ethics. 2011;101:619–633. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwetsloot G.I.J.M. From management systems to corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics. 2003;44:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Value”, 2nd meaning, Oxford Dictionary Online [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 Jan 15]. Available from: http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/value?q=value.

- 19.British Quality Foundation (BQF) 2013. Glossary of the European Foundation for Quality Management's excellence model terms, BQF [Internet] [cited 2013 Feb 14]. Available from: http://www.bqf.org.uk/efqm-excellence-model/glossary-terms. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cambridge Dictionary (CD) 2013. “Core value”, CD Online [Internet] [cited 2013 Jan 15]. Available from: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/core_1?q=core+value#core_1__3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hostede G. 2nd ed. SAGE; Thousand Oaks (CA): 2001. Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviours, institutions and organisations across nations; p. 597 p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofstede G., Hostede G.J., Minkov M. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; New York (NY): 2010. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind; p. 560 p. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider S.C. National vs. corporate culture: implications for human resource management. Hum Resour Manage. 2006;27:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senge P. Doubleday; New York (NY): 1990. The fifth discipline – art and practice of the learning organisation; p. 424 p. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters T.J., Waterman R.H. Harper & Collins; New York (NY): 1982. In search for excellence. [Google Scholar]

- 26.2nd Strategy Conference. Five pillars for a culture of prevention in business and society – strategies on safety and health at work, February 3–4, 2011, DGUV Academy Dresden [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2012 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.dguv.de/iag/en/veranstaltungen_en/strategie2011/index.jsp.

- 27.Zwetsloot G.I.J.M., Aaltonen M., Wybo J.L., Saari J., Kines P., Op De Beeck R. The case for research into the zero accident vision. Saf Sci. 2013;58:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alli B.O. International Labour Organisation; Geneva (Switzerland): 2008. Fundamental principles of occupational health and safety; p. 221 p. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghai D. Decent work, concept and indicators. Int Labor Rev. 2008;142:113–145. [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Labour Organisation. Questions and answers on business and occupational safety and health [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 May 2]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/business-helpdesk/WCMS_DOC_ENT_HLP_OSH_FAQ_EN/lang--en/index.htm#F12.

- 31.Schein E. A conceptual model for managed culture change. In: Schein E., editor. Organisational culture and leadership. 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco (CA): 1997. p. 406 p. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giddens A. 5th ed. Polity Press;; Cambridge (UK): 1991. The constitution of society; p. 402 p. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schein E. The new workplace: transforming the character and culture of our organizations. Pegasus Communications; Waltham (MA): 2007. Can learning cultures evolve? pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schein E. 1st ed. Jossey Bass; San Francisco (CA): 2009. The corporate culture survival guide. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yassi A. Health promotion in the workplace – the merging of paradigms. Methods Inf Med. 2005;2:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goetzel R.Z., Shechter D., Ozminkowski R.J., Marmet P.F., Tabrizi M.J., Roemer E.C. Promising practices in employer health and productivity management efforts: findings from a benchmarking study. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:111–130. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31802ec6a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enterprise for Health (EfH) Bertelsmann Stiftung; Gütersich (German): 2005. Guide to best practice – driving business excellence through corporate culture and health; p. 98 p. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enterprise for Health (EfH) Bertelsmann Stiftung; Gütersich (German): 2006. Healthy lifestyles and corporate culture; p. 20 p. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organisation (WHO) WHO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2010. Healthy workplaces: a model for action – for employers, workers, policy-makers and practitioners; p. 32 p. [Google Scholar]

- 40.European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP) ENWHP; Essen (German): 2007. Luxembourg declaration on workplace health promotion in the European Union, updated version; p. 6 p. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leka S., Cox T. I-WHO Publications; Nottingham (UK): 2008. The European Framework for Psychosocial Risk Management – European Framework; p. 184 p. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox S., Cox T. The structure of employees attitudes to safety: an European example. Work Stress. 1991;5:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee T.R. Perceptions, attitudes and behaviour: the vital elements of a safety culture. Health Saf. 1996;10:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGregor D. McGraw-Hill; New York (NY): 1960. The human side of the enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisbord M.R. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco (CA): 2012. Productive workplaces, dignity, meaning and community in the 21st Century. 25th anniversary; p. 506 p. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beer M. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco (CA): 2009. High commitment – high performance – how to build a resilient organization for sustained advantage; p. 390 p. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartholomew L.K., Parcel G.S., Kok G., Gottlieb N.H., Fernandez M.E. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco (CA): 2011. Environment-oriented theories; pp. 113–170. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Employment Conditions Knowledge Network (EMCONET) World Health Organisation; Geneva (Switzerland): 2007. Employment conditions and health inequalities – final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- 49.European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) EU OSHA; Bilbao (Spain): 2011. Occupational Safety and Health culture assessment – a review of main approaches and selected tools; p. 79 p. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooperrider D., Srivastva S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Res Org Change Development. 1987;1:129–169. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessels J., Boers E., Mostert P. Boom; Amsterdam [Netherlands]: 2002. Vrije ruimte –Filosoferen in organisaties [Free space – Philosophy in organizations] p. 246 p. [in Dutch] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown D., Isaacs J. Berret Koehler Publishers; San Francisco (CA): 2005. The World Café: shaping our futures through conversations that matter; p. 242 p. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karasek R.A., Theorell T. Basic Books; New York (NY): 1990. Healthy work: stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life; p. 381 p. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huber M., Knottnerus J.A., Green L., van der Horst H., Jadad A.R., Kromhout D., Leonard B., Lorig K., Loureiro M.I., van der Meer J.W.M., Schnabel P., Smith R., van Weel C., Smid H. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hollnagel E., Woods D., Leveson N. Ashgate Publishers; Burlington (VT): 2006. Resilience engineering – concepts and precepts, Hampshire; p. 397 p. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psy. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Markus H.R., Shinobu K. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psy Rev. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dutton J.E. Breathing Life into organizational studies. J Man Inquiry. 2003;12:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dutton J.E., Heaphy E.D. The power of high quality connections. In: Cameron K., Dutton J.E., Quinn R.E., editors. Positive organizational scholarship. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; San Francisco (CA): 2003. pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guest D. Human resource management, corporate performance and employee wellbeing: building the worker into HRM. J Ind Relations. 2002;44:335–358. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Authority of Canberra Territory Public Service (ACTPS) ACTPS; Canberra (Australia): 2010. Respect, equity and diversity framework – creating great workplaces with positive cultures; p. 29 p. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siegrist J. The adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occ Health Psy. 1996;1:27–41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menon S.T. Employee empowerment: an integrative psychological approach. Appl Psy. 2001;50:153–180. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallerstein N.B., Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Prom Pract. 2006;7:312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2011. Social determinants – approaches to public health; p. 223 p. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blas E. From concept to practice – synthesis of findings. In: Blas E., Sommerfeld J., Kurup A.S., editors. Social determinants – approaches to public health. World Health Organisation; Geneva (Switzerland): 2011. pp. 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burke M.J., Scheuer M.L., Meredith R.J. A dialogical approach to skill development: the case of safety skills. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2007;17:235–250. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Argyris C. Blackwell Publishing; Malden (MA): 1990. On organizational learning; p. 454 p. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marmot M., Ellen J., Bell R., Bloomer E., Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380:1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weick K.E., Sutcliffe K.M. 2nd ed. Jossey Bass; San Francisco (CA): 2007. Managing the unexpected; p. 194 p. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hudson P.T.W., Parker D., Lawton R., Verschuur W.L.G., van der Graaf G., Kalff J. SPE; Stavanger (Norway): 2000. The hearts and minds project, creating intrinsic motivation for HSE. Paper presented at the SPE International Conference on Health Safety Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scharmer C.O. SOL; Cambridge (UK): 2007. Theory U – leading for the future as it emerges – the social technology of presencing; p. 534 p. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dekker S. 2nd ed. Ashgate Publishers; Aldershot (UK): 2012. Just culture, balancing safety and accountability; p. 171 p. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ybema J.F., van den Bos K. Effects of organizational justice on depressive symptoms and sickness absence: a longitudinal perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1609–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van der Zouwen T. Eburon; Delft (Netherlands): 2011. Building an evidence based practical guide to Large Scale Interventions [doctoral thesis] p. 304 p. [Google Scholar]

- 76.EU European Council Framework directive 89/391 . EU European Council; Brussels (Belgium): 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aalders T., Wilthagen T. Moving beyond command and control: reflexivity in the regulation of occupational safety, health and environment. Law Policy. 1997;19:415–443. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Breda A. Resilient workplaces: an in initial conceptualization, families in society. J Contemp Soc Serv. 2011;92:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tehrani N., editor. Building a culture of respect – managing bullying at work. Taylor & Francis; New York (NY): 2001. p. 224 p. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martin Egge S.A. Creating an environment of mutual respect within the multicultural workplace both at home and globally. Manag Decis. 1999;37:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 81.International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) ICCA/CEFIC (The European Chemical Industry Council); Brussels (Belgium): 2006. Responsible care – global charter; p. 16 p. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cornelis A. Boom; Meppel (Netherlands): 1988. Logica van het gevoel [The logic of feeling] p. 434 p.. [in Dutch] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maslow A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psy Rev. 1943;50:370–396. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weick K.E. SAGE; New York (NY): 1995. Sense making in organizations; p. 230 p. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Evans J. Employment, social inclusion and mental health. J Psy Ment Health Nurs. 2000;7:15–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jamali D. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: a fresh perspective into theory and practice. J Bus Ethics. 2008;82:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burns C., Mearns K., Mc George P. Explicit and implicit trust within safety culture. Risk Anal. 2006;26:1139–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kouvonen A., Kivimäki M., Vahtera J., Oksanen T., Elovainio M., Cox T., Virtanen M., Pentti J., Cox S.J., Wilkinson R.G. Psychometric evaluation of a short measure of social capital at work. BCM Public Health. 2006;6:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oksanen T., Kouvonen A., Kivimäki M., Pentti J., Virtanen M., Linna A., Vahtera J. Social capital at work as a predictor of employee health: multilevel evidence from work units in Finland. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Törner M. The social-physiology of safety. An integrative approach to understanding organisational psychological mechanisms behind safety performance. Saf Sci. 2011;49:1262–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 91.European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) EU-OSHA; Bilbao (Spain): 2010. Mainstreaming OSH into business management; p. 196 p. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kines P., Lappalainen J., Mikkelsen K.L., Olsen E., Pousette A., Tharaldsen J., Tómasson K., Törner M. Nordic safety climate questionnaire (NOSACQ-50): a new tool for diagnosing. Int J Ind Ergon. 2011;41:634–646. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2nd ed. OECD; Paris (France): 2008. Guidance on developing safety performance indicators – related to chemical accident prevention, preparedness and response; p. 156 p. OECD Environment Health and Safety Publications No 19. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mearns K., Whitaker S.M., Flin R. Safety climate, safety management practice and safety performance in offshore environments. Saf Sci. 2003;41:641–680. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cox T., Karanika M., Griffiths A., Houdtmont J. Evaluating organizational-level work stress interventions: beyond traditional methods. Work Stress. 2007;21:348–362. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sørensen O.S., Hasle P., Pejtersen J.H. Trust relations in management of change. Scand J Manag. 2011;27:405–417. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Conchie S.M., Donald I.J. The functions and development of safety-specific trust and distrust. Saf Sci. 2008;46:92–103. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Conchie S.M., Donald I.J., Taylor P.J. Trust: missing piece(s) in the safety puzzle. Risk Anal. 2006;26:1097–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Corbett D. Excellence in Canada: healthy organisations; achieve results by acting responsibly. J Bus Ethics. 2004;55:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Milliman J., Czaplewski A.J., Ferguson J. Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes. J Org Change Manag. 2003;16:426–447. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schein EH. Three cultures of management: The key to organizational learning. MIT Sloan Manage Rev 1996 Fall;38:9–20.

- 102.Sowden P., Sinha S. Health and Safety Executive; Norwich (UK): 2005. Promoting health and safety as a key goal of the corporate social responsibility agenda; p. 45 p. Research Report 339. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74:236–244. [Google Scholar]