Abstract

Introduction:

Vaginal discharge is one of the common reasons for gynecological consultation. Many of the causes of vaginitis have a disturbed vaginal microbial ecosystem associated with them. Effective treatment of vaginal discharge requires that the etiologic diagnosis be established and identifying the same offers a precious input to syndromic management and provides an additional strategy for human immunodeficiency virus prevention. The present study was thus carried out to determine the various causes of vaginal discharge in a tertiary care setting.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 400 women presenting with vaginal discharge of age between 20 and 50 years, irrespective of marital status were included in this study and women who had used antibiotics or vaginal medication in the previous 14 days and pregnant women were excluded.

Results:

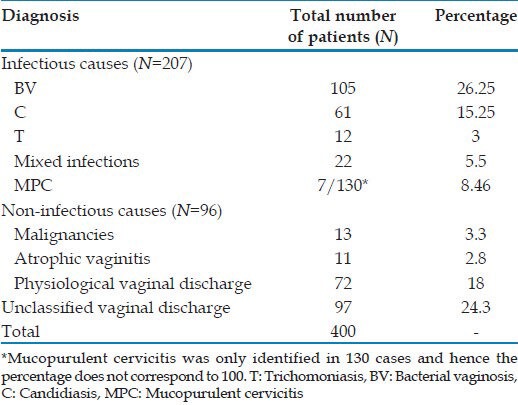

Of the 400 women with vaginal discharge studied, a diagnosis was established in 303 women. Infectious causes of vaginal discharge were observed in 207 (51.75%) women. Among them, bacterial vaginosis was the most common cause seen in 105 (26.25%) women. The other infections observed were candidiasis alone (61, 15.25%), trichomoniasis alone (12, 3%), mixed infections (22, 5.5%) and mucopurulent cervicitis (7 of the 130 cases looked for, 8.46%). Among the non-infectious causes, 72 (18%) women had physiological vaginal discharge and 13 (3.3%) women had cervical in situ cancers/carcinoma cervix.

Conclusion:

The pattern of infectious causes of vaginal discharge observed in our study was comparable with the other studies in India. Our study emphasizes the need for including Papanicolaou smear in the algorithm for evaluation of vaginal discharge, as it helps establish the etiology of vaginal discharge reliably and provides a valuable opportunity to screen for cervical malignancies.

KEY WORDS: Bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, mucopurulent cervicitis, Trichomonas vaginalis, trichomoniasis, vaginal discharge

INTRODUCTION

Vaginal discharge is one of the common reasons for gynecological consultation. Not all women with vaginal symptoms have vaginitis; approximately 40% of women with vaginal symptoms will have some type of vaginitis.[1] Despite the control over the vaginal micro-environment exerted by the lactobacilli, many other microorganisms can be cultivated from the vaginal samples of healthy women. These organisms do not trigger a pathological state, but when one class of them dominates, the resulting imbalance precludes to vaginitis/vaginosis. The common infectious causes of vaginitis include anaerobic bacteria causing bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis and trichomonal vaginitis.[1] The uncommon infectious causes include atrophic vaginitis with secondary bacterial infection, foreign body with secondary infection, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (clindamycin responsive), streptococcal vaginitis (Group A), ulcerative vaginitis associated with Staphylococcus aureus and idiopathic vulvovaginal ulceration associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Identifying the infectious source of vaginal discharge can be challenging, because a large number of pathogens cause vaginal and cervical infection and several infections may co-exist. Patient's history and physical examination findings along with appropriate tests may suggest a diagnosis. Effective treatment of vaginal discharge requires that the etiologic diagnosis be established and identifying the same offers a precious input to syndromic management and provides an additional strategy for HIV prevention.

The present study was thus carried out to determine the various causes of vaginal discharge in a tertiary care setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject

This was a hospital-based descriptive study done on 400 female patients with vaginal discharge, who attended the Obstetrics and Gynecology out-patient Department of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry from May 2010 to July 2011. The Institute Ethics Committee clearance was obtained and informed consent was taken from the recruited women. Inclusion criteria: Women presenting with vaginal discharge of age between 20 and 50 years, irrespective of marital status were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: Women who had used antibiotics or vaginal medication in the previous 14 days and pregnant women were excluded from the study.

A detailed history was elicited and a thorough genital examination was done and abnormalities in the vulva, vagina and cervix were noted. The amount, odor, color and consistency of vaginal discharge were noted. The discharge was labeled scanty if it was insufficient to collect on the speculum; moderate if it was sufficient to collect on the speculum and profuse if it was visible at the introitus even before speculum insertion. The vaginal pH was measured directly using pH indicator strips against the lateral vaginal wall.

Clinical investigation

A sterile cotton swab was used to collect the vaginal discharge from the posterior vaginal fornix under direct vision and the specimen thus obtained was subjected to a series of laboratory tests. However, in virgin females, the specimen was obtained from the introitus. The Papanicolaou smears (Pap smears) were taken by doctors or well-trained nurses and conventional smears were obtained and processed using automated cytology machine. A bimanual examination was done in all except virgins to look for adnexal tenderness.

From each patient examined, five samples of vaginal discharge from the posterior fornix were collected with sterile cotton swabs. The first swab was subjected immediately to wet mount microscopy to observe for motile trichomonads under ×100 and ×400 magnifications. With the second sample, a 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount was prepared and whiffed for the presence of fishy odor (Amine test) and the same was examined for the presence of budding yeast cells under ×100 and ×400 magnifications. The third sample was immediately inoculated directly and swirled into the Diamond medium (Himedia labs, Mumbai, India) for Trichomonas vaginalis culture. The culture tubes with 5 ml of the broth were incubated in anaerobic atmosphere at 35°C. The fourth sample was inoculated on to Sabouraud's dextrose agar medium for candidial culture and for sensitivity to fluconazole and amphotericin B by disc diffusion method. The fifth sample was streaked on to a microscopic slide for Gram stain for the presence of clue cells, yeast cells and pus cells under ×1000 magnification. Women with high-risk sexual behavior were counseled and tested for HIV antibodies.

The diagnoses of different vaginal diseases are as follow:

-

Trichomoniasis[2] was based on:

- Wet mount: Pear shaped organisms approximately the same size as that of a lymphocyte (10-20 μm) or that of a small neutrophil with characteristic jerky movements

- Pap smear: Blue or grey pear-shaped organisms with bright red granules; other features include moderate to marked inflammatory response and a proteinaceous blue-grey background

- Culture: Diagnosis was made by performing wet mounts for evidence of motile trichomonads by examining cultures after 24 h of incubation and then daily for upto 7 days. For culture, Diamond medium (Himedia labs, Mumbai, India) with fetal calf serum was used. The culture tubes with 5 ml of broth were incubated in anaerobic atmosphere at 35°C.

-

BV was based on Amsel's criteria[3] in which the presence of three out of four criteria is necessary;

- Excessive homogenous uniformly adherent vaginal discharge

- Vaginal pH more than 4.5

- Positive amine test (Whiff test) – vaginal discharge collected from the posterior fornix of vagina was swabbed onto a glass slide followed by the addition of 10% of potassium hydroxide (KOH). Presence of a fishy odor was taken as a positive Whiff test

- Presence of clue cells on microscopic examination.

Candidiasis was based on positive microscopy characterized by the presence of budding yeast cells and/or culture on Sabouraud's dextrose agar medium.

Mucopurulent cervicitis (MPC) defined as the presence of 30 or more polymorphonuclear leukocytes per oil immersion field in cervical mucus.[4] Those patients who do not fulfill the above diagnostic criteria with inflammatory changes on Pap smear and Gram stain, were reviewed and endocervical swabs were taken for Gram's stain to look for this condition.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was tabulated in Microsoft Excel Worksheet and computer-based analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). For comparison of means, unpaired t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for two and more than two groups respectively. For comparison of proportions, Chi-square test was used. In cases where any one of cell value was less than five, Fisher's exact test was used. For comparison within the group, Chi-square test was used.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics

The mean age of the 400 recruited women was 35.24 ± 8.37 years (ranging from 20 to 50 years with a median of 35 years). Majority (254, 63.5%) of our patients belonged to the upper lower socio-economic class (Class IV) as per Kuppuswamy's socio-economic status scale-updating for 2007. Most (358, 89.5%) of these women were married and living with husband; 22 (5.5%) were widows, 12 (3%) were married but separated from their husbands and 8 (2%) of them were unmarried.

Risk and behavioral characteristics

A history of premarital or extramarital contact was present in 15 (3.8%) women, out of which 12 (3%) women had extramarital contact with one other partner and 3 (0.8%) women had premarital contact. Out of the 392 women (excluding unmarried women), 306 (78.06%) women denied the history of husband having extramarital contact while 49 (12.5%) women gave a positive response. However, 37 (9.4%) women were not aware of their husband's extramarital status. Out of the 393 women (excluding unmarried women except one who had a premarital contact), 19 (5%) women had symptomatic partners with dysuria (9, 2.4%) being the most comon symptom. Majority (288, 72%) of the recruited women were tubectomised. 6 (1.5%) women used barrier contraceptives. 4 (1%) women had previous pelvic inflammatory disease and 4 (1%) had primary infertility. 3 (0.8%) out of 400 women in our study population consumed alcohol while none of the women had a history of smoking or drug addiction.

Disease characteristics

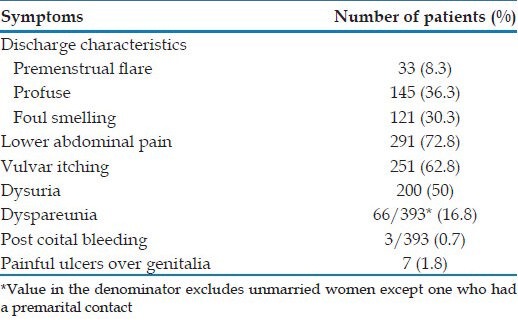

The mean duration of vaginal discharge in our study was 14.08 ± 26.64 months (ranging from 1 day to 20 years with a median of 3 months). Of the 400 women with vaginal discharge in our study, the most common associated symptom was lower abdominal pain seen in 291 (72.8%) women. The other symptoms the women presented with are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Symptoms in the women in our study

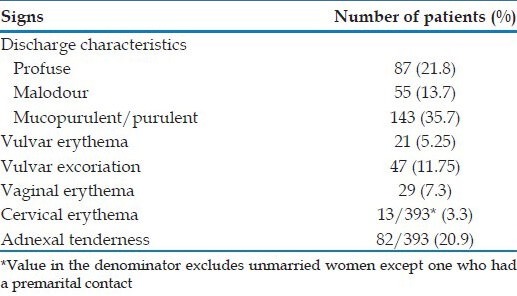

In the 400 women examined, the various clinical findings were as follows: Profuse discharge in 21.8%, malodourous discharge in 13.7%, mucopurulent/purulent discharge in 35.7%, vulvar erythema and excoriation in 5.25% and 11.75% of patients respectively, vaginal erythema in 7.3% and cervical erythema in 3.3% and adnexal tenderness in 20.9%. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examination findings in women with vaginal discharge in our study

Spectrum of vaginal discharge

In our study, on 400 women, 207 (51.7%) women with vaginal discharge were found having infectious causes (BV, candidiasis, trichomoniasis, mixed infections and mucopurlent cervicitis), while 96 of them had non-infectious causes (malignancies, atrophic vaginitis and physiological discharge). In 97 women the cause of vaginal discharge could not be classified into any of the above categories. The different causes of vaginal discharge as analyzed after studying the symptoms, signs and investigations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Spectrum of vaginal discharge in our study population

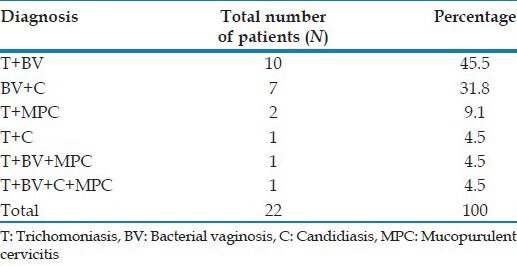

Out of the 22 women with mixed infections, majority (12, 54.5%) were concurrently infected with trichomoniasis and BV. The various mixed infections observed in the study are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mixed infections in our study population

Co-existent sexually transmitted infections

Out of the 86 (21.5%) women at risk, 7 (8.13%) were reactive for HIV serology. 7 (1.75%) women had herpes genitalis at presentation, with one of them having concurrent HIV infection. Five of the seven with herpes genitalis had BV, while one had candidiasis and one had MPC.

DISCUSSION

Among the 400 women presenting to the Obstetrics and Gynecology out-patient department with the complaints of vaginal discharge and recruited in our study, a diagnosis was established in 303 women, of which 72 (18%) women had physiological vaginal discharge. A diagnosis could not be established in 97 (24.2%) women. Infectious causes of vaginal discharge were observed in 207 (51.75%) women. Endogenous infections were relatively common; namely BV in 124 (31%) cases and candidiasis in 70 (17.5%) cases. T. vaginalis infection was identified in 27 (6.75%) cases. This was comparable to the observations made by Patel et al.[5] in their population based study on 2494 women of reproductive age group in Goa. BV was observed in 17.8% of cases and candidiasis in 8.5% cases; together constituted the most common cause of reproductive tract infection in their study. The spectrum of vaginal discharge, similar to that seen in our study was observed by Vishwanath et al.[6] in their study on symptomatic women attending reproductive health clinic in New Delhi; wherein BV was diagnosed in 26% cases, candidiasis in 25.4% and trichomoniasis in 10% cases. Similarly, in a population based study from both rural and urban communities by Bhalla et al.[7] on women in reproductive age group, the most common infection was BV (32.8%), followed by candidiasis (16.9%); trichomoniasis was diagnosed in 2.8% cases. A study performed by Puri et al.,[8] on 100 sexually active women presenting with vaginal discharge revealed BV in 45% cases, candidiasis in 31%, trichomoniasis in 2%, gonorrhea in 3% and non-specific uro-genital causes in 5% of cases. The similar trends in the Indian studies may be attributed to a conservative Indian society, where premarital or extramarital sexual contact is an exception rather than the rule. Hence, BV and candidiasis, whose spread by sexual transmission is doubtful, are more prevalent when compared to trichomoniasis.

This was in contrast to the study by Fonck et al.,[9] where candidiasis was more prevalent (46%), followed by trichomoniasis (21% cases) and BV (10%). The higher percentage of trichomoniasis in this study, was probably because the study population was recruited from major sexually transmitted infection (STI) referral clinics in Kenya. Dan et al.,[10] in their study on symptomatic women of reproductive age recruited from a gynecologic clinic in Israel also reported candidiasis as the most common (35.5%) infection, followed by BV in 23.5% of women and trichomoniasis in 8.1% women. Zimba et al.[11] found BV in 34% cases, gonorrhea in 11% of cases, Chlamydia infection in 7% cases, trichomoniasis in 2%, mixed infections in 11% and no definite laboratory diagnosis in 22% cases. El Sayed Zaki et al.[12] found BV in 39.1% of patients, trichomoniasis in 30% and Mycoplasma hominis infection in 14.5% of patients.

Among the mixed infections in our study, concurrent trichomoniasis with BV was the most common. Mixed infections were observed in 22 (5.5%) cases in our study, probably underestimating the actual prevalence because only 130 out of the 400 women were examined for MPC. de Lima Soares et al.,[13] in their study on women of reproductive age living in rural communities in north-east Brazil observed that multiple infections were common in their study, with two or more curable STIs occurring in 15% of women. A similar high frequency of multiple infections (30.1%), was observed by Pickering et al.[14] in their study from rural southwest Uganda.

Cancers of the cervix constitute an important cause of vaginal discharge among the non-infectious causes. In our study, cervical cancer in situ and invasive cervical cancers were identified in 13 (3.3%) cases. This was comparable to the observation by García et al.,[15] who in their study on reproductive tract infections in rural women from highlands and coastal regions of Peru, found 4.3% cases with evidence of invasive cervical cancers and cervical dysplasias. Hence, meticulous per speculum examination for evidence of obvious growths in the cervix and use of Pap smear in the algorithm for diagnosis of vaginal discharge would provide a valuable opportunity for screening for these carcinomas. This investigation will be relevant for reproductive age group especially those in 40 years and above, married or single but sexually active with more than one partner.

CONCLUSION

The pattern of infectious causes of vaginal discharge observed in our study was comparable to the other studies in India with the majority being endogenous infections. A moderate prevalence of T. vaginalis infection was observed. Our study emphasizes the need for including Pap smear in the algorithm for evaluation of vaginal discharge, as it helps establish the etiology of vaginal discharge reliably and provides a valuable opportunity to screen for cervical malignancies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sobel J. Vaginitis, vulvitis, cervicitis and cutaneous vulval lesions. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, editors. Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. Spain: Elsevier Ltd; 2004. pp. 683–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domeika M, Zhurauskaya L, Savicheva A, Frigo N, Sokolovskiy E, Hallén A, et al. Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of trichomoniasis in East European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1125–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thappa DM, Adityan B. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Sharma VK, editor. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS. 2nd ed. India: Viva Books Pvt. Ltd; 2009. pp. 398–406. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wølner-Hanssen P, Krieger JN, Stevens CE, Kiviat NB, Koutsky L, Critchlow C, et al. Clinical manifestations of vaginal trichomoniasis. JAMA. 1989;261:571–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420040109029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V, Weiss HA, Mabey D, West B, D’Souza S, Patil V, et al. The burden and determinants of reproductive tract infections in India: A population based study of women in Goa, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:243–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vishwanath S, Talwar V, Prasad R, Coyaji K, Elias CJ, de Zoysa I. Syndromic management of vaginal discharge among women in a reproductive health clinic in India. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:303–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhalla P, Chawla R, Garg S, Singh MM, Raina U, Bhalla R, et al. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis among women in Delhi, India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puri KJ, Madan A, Bajaj K. Incidence of various causes of vaginal discharge among sexually active females in age group 20-40 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonck K, Kidula N, Jaoko W, Estambale B, Claeys P, Ndinya-Achola J, et al. Validity of the vaginal discharge algorithm among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:33–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dan M, Kaneti N, Levin D, Poch F, Samra Z. Vaginitis in a gynecologic practice in Israel: Causes and risk factors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:629–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimba TF, Apalata T, Sturm WA, Moodley P. Aetiology of sexually transmitted infections in Maputo, Mozambique. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:41–7. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Sayed Zaki M, Raafat D, El Emshaty W, Azab MS, Goda H. Correlation of Trichomonas vaginalis to bacterial vaginosis: A laboratory-based study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:156–63. doi: 10.3855/jidc.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lima Soares V, de Mesquita AM, Cavalcante FG, Silva ZP, Hora V, Diedrich T, et al. Sexually transmitted infections in a female population in rural north-east Brazil: Prevalence, morbidity and risk factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:595–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering JM, Whitworth JA, Hughes P, Kasse M, Morgan D, Mayanja B, et al. Aetiology of sexually transmitted infections and response to syndromic treatment in southwest Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:488–93. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García PJ, Chavez S, Feringa B, Chiappe M, Li W, Jansen KU, et al. Reproductive tract infections in rural women from the highlands, jungle, and coastal regions of Peru. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:483–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]