Abstract

Introduction:

Intestinal parasitic infestation is a major public health problem in children of developing countries Because of poor socio-economic conditions and lack of good hygienic living. The aims of this study were to measure the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestations and to identify risk factors associated with parasitic infestations among the school children of Itahari Municipality.

Materials and Methods:

The cross-sectional study was conducted in Grade VI, VII and VIII in Government and private schools of Itahari Municipality. Stratified random sampling method was applied to choose the schools and the study subjects. Semi-structured questionnaire was administered to the study subjects and microscopic examination of stool was done. The Chi-square test was used to measure the association of risk factors and parasitic infestation.

Results:

Overall intestinal parasitic infestation was found to be 31.5%. Around 13% of the study population was found to be infested with helminthes and 18.5% of the study population was protozoa infected. Not using soap after defecation, not wearing sandals, habit of nail biting and thumb sucking were found to be significantly associated with parasitic infection.

Conclusions:

The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation was found to be high in school children of Itahari. Poor sanitary condition, lack of clean drinking water supply and education is supposed to play an important role in establishing intestinal parasitic infections.

KEY WORDS: Nepal, parasitic infestation, prevalence, risk factors, school children

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal parasitic infections are among the most common infections world-wide.[1] Intestinal parasitic infection varies considerably from place to place in relation to the disease.[2] According to the World Health Organization estimate; globally there are 800-1000 million cases of Ascariasis, 700-900 million of Hook Worm infection, 500 millions of Trichuriasis, 200 million of Giardiasis and 500 million of Entamoeba histolytica.[3]

Intestinal helminth infestations are the most common infestations among school age children and they tend to occur in high intensity in this age group.[4] Helminthic infestation lead to nutritional deficiency and impaired physical developments, which will have negative consequences on cognitive function and learning ability.[5]

Infections due to intestinal parasites are common throughout the tropics, posing serious public health problems in developing countries.[6,7] In many parts of the world the high prevalence rate of intestinal parasite is attributed largely to low socio-economic status, poor sanitation, inadequate medical care and absence of safe drinking water supplies.[6,7] Therefore, this study was designed to measure the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation and to identify risk factors associated with parasitic infestation among the school children of Itahari Municipality.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The cross-sectional study was conducted from 15th November 2011 to 14th March 2012 in Grade VI, VII and VIII in Government and private schools of Itahari Municipality. Stratified random sampling method was applied to choose the schools and the study subjects. Out of total 47 schools in Itahari Municipality, seven were Government (15%) and 40 were private schools (85%).

To represent children for atleast 66.2% intestinal parasitic infection, the sample size was calculated as 200 based on the prevalence of 66.2%, 95% confidence level and 10% allowable error. The required sample size is 200 children aged 12-15 years (Agbolade et al. in 2007). Out of 200, 15% (30) were taken from Government schools and 85% (170) were taken from private schools on the basis of probability proportionate to sample size. Study subjects were enrolled until the required sample size was fulfilled.

Written permission was taken from each schools head and verbal consent was taken from each student. Students of Grade VI, VII and VIII of both sexes, who were available after three visits and willing to give verbal consents, were included in the study.

Semi-structured questionnaire was administered to the study subjects and microscopic examination of stool was done. In each visit more than 20 students were enrolled and the same number of plastic bottles was given for stool collection and collected the next day morning. Microscopic examination of stool was done by preparing slide using Normal Saline and Lugol's Iodine to observe the ova of different parasites. First we used low power lens and afterward the high power lens. Then we observed ova, cyst of parasites.[8]

The Chi-square test was used to measure the association of risk factors and parasitic infestation. The confidence level was set at 5% in which probability of occurrence by chance will be significant if P < 0.05 with 95% Confidence Interval.

RESULTS

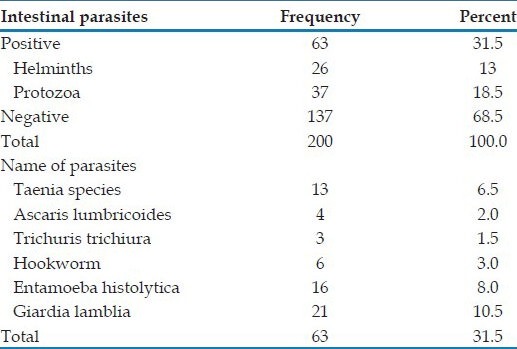

Table 1 shows almost one-third of the population (31.5%) were infested with intestinal parasites. Protozoa was seen more among the population than helminths. Taenia species was seen highest among the Helminth infestation and Giardia lamblia was seen higher than Entamoeba histolytica among protozoans.

Table 1.

Distribution of parasitic infestation among study population

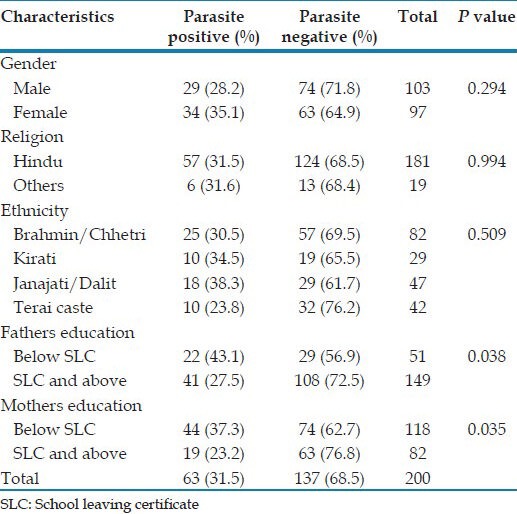

The prevalence of parasitic infestation was seen higher in female than male, but the difference was not significant. The parasitic infestation was higher among children whose parent's education was below School leaving certificate (SLC) than whose parent's education was SLC and above [Table 2].

Table 2.

Association between socio-demographic characteristics with parasitic infestation

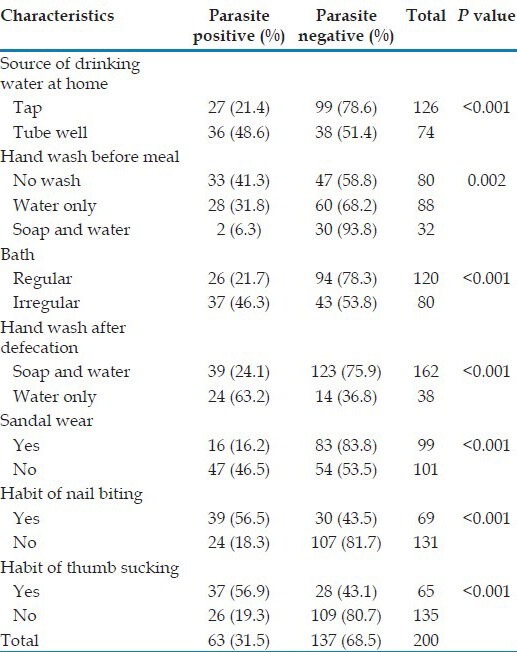

Table 3 shows the children those using soap and water after defecation had significantly lower prevalence of parasitic infestation than those using only water. The infestation was seen higher among children having the habit of nail biting and thumbs sucking.

Table 3.

Association between personal hygiene with parasitic infestation

DISCUSSION

Studies on estimated disease burdens show that globally, 39 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost due to intestinal helminthiasis. This model also estimated that 70% of the total burden of diseases is due to soil transmitted helminthes infections, which could be prevented in high-prevalence communities by treating school-age children.[9]

The present study assessed the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among school children of Itahari Municipality. The overall prevalence of intestinal parasites in this study was (31.5%), which is relatively low compared with that reported by Merid et al. in Lake Awassa Area, South Ethiopia (92.7%),[10] Dagnew et al. In Ethiopia (61%)[11] and Wani et al. In Srinagar city, Kashmir, India (46.7%).[12] Itahari is a comparatively developed town with only a small number of people working in the fields. Furthermore, the periodic campaign of anti-helminthic drug administration to the children could possibly explain the lower prevalence of helminthic infections seen in this study.

This study showed relatively high prevalence of Taenia (6.5%) compared with that reported by Merid et al. in South Ethiopia (1.4%).[10] However, the prevalence of Taneia infestation in this study was lower than the study conducted by Joshi et al. in Nepal which showed the prevalence of taeniasis among the ethnic groups surveyed, i.e., Magars, Sarkies, Darai and bote was found to be 50%, 28%, 10%, and 30%, respectively. Magar people are known for rearing pigs and eating much more pork than other ethnic groups, while the Sarkies are the poorest of the ethnic groups and are known to consume rotting cattle carcasses.[13]

The parasitic infestation among the male was lower (28.2%) than female (35%) but the difference was not significant. A study conducted by Shakya in Dhankuta and Sunsari, Nepal also showed that the prevalence of parasite infestation was slightly lower in male (65%) than female (66%).[14] However, the study conducted by Tadesse in Ethiopia showed the prevalence of parasitic infestation among male was higher (28.8%) than female (24.3%).[15] This indicated that the gender may or may not play the role in parasitosis depending up on the region and other environmental or behavioral factors. In general, the increased mobility of the male increases the risk of infection among them, while female have more soil contact during growing vegetables and eat raw vegetable with prepared food more often than males.

Prevalence of parasitic infestation in Janajati/Dalit in combined form was higher than other ethnic groups, but the difference was not significant. A study conducted in Nepal by Rai also showed high prevalence of stool positive among Dalits.[16]

The parasitic infestation was significantly higher among children whose mothers’ education was below SLC (37.3%) than whose mothers’ education was SLC and above (23.2%). Studies conducted by Bisht et al. in India[17] and Celiksöz et al. in Turkey[18] also showed higher prevalence of parasitic infections whose mothers were uneducated than educated mother.

Children using source of drinking water as tube well had significantly higher prevalence of parasitic infestation (48.6%) than using tap water (21.4%). A study conducted by Awasthi et al. in India also showed a strong association between intake of tube well water and occurrence of infection (P < 0.001).[19]

Children using soap and water before meal had significantly lower prevalence of parasitic infestation (6.3%) when compared with hand washing only using water (31.8%) and who did not wash hand (41.3%). Another study also showed a higher rate of parasitic infection among children who didn’t wash their hands regularly before meals (P < 0.05).[15] This study showed that the children washing hand with soap and water after defecation had significantly lower prevalence of parasitic infestation (24%) when compared with washing hand only using water (63.2%). The similar studies conducted in India also showed lower prevalence of parasitic infection who were using soap and water for hand washing after defecation than using only water.[17,19]

Regular wearing of sandal or shoes had a significantly lower prevalence of parasitic infections (16.2%) than those did not wear sandal or shoes (46.5%). A similar study conducted in Ethiopia also showed that regular wearing of shoes had a significant contribution to the low prevalence rate of parasitic infections (P < 0.05).[15]

Prevalence of parasitic infestation among having the habit of nail biting was significantly higher (56.5%) than not having the habit of nail biting (18.3%). A similar study conducted by Sah in Dharan, Nepal showed similar trend where prevalence of parasitic infestation among having the habit of nail biting was higher (13.6%) than not having the habit of nail biting (10.7%).[20]

Limitations of this study: Firstly, we conducted single stool examination for detection of intestinal parasitic infections, which could have underestimated the prevalence, as optimal laboratory diagnosis of intestinal parasitic infections requires the examination of at least three stool specimens collected over several days.[21] Secondly, it was planned to conduct stool sample testing within 2 h of collection; however, due to logistic constraints, it was delayed at times from 3 to 6 h as a result of which we could not detect the invasive intestinal parasites.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of overall intestinal parasitic infestation was high among school children of Itahari. Poor hygiene and sanitary condition, lack of clean drinking water supply and education is supposed to play important role in establishing intestinal parasitic infections. This advocates the use of various deworming schedule periodically in school to cure the children and to break the transmission chain of these intestinal parasitic illnesses along with supply of clean drinking water and Health education regarding hygienic practices in the school at primary levels can have substantial effect in prevention of intestinal parasites among the children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank to School of Public Health and Community Medicine for approval of our research work. We are grateful to B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences for providing grant for the research in 2011. Our gratitude and sincerely thanks to all the participants of study from Schools of Itahari and teachers for their kind co-operation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kang G, Mathew MS, Rajan DP, Daniel JD, Mathan MM, Mathan VI, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in rural Southern Indians. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:70–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luka SA, Ajoi I, Umoh JU. Helminthosis among primary school children in statem, Nigerian. Niger J Parasitol. 2000;21:109–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roma B, Worku S. Magnitude of Schistogoma mansoni and intestinal helminthic infections among school children in wondogenet zuria, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1997;11:125–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albonico M, Crompton DW, Savioli L. Control strategies for human intestinal nematode infections. Adv Parasitol. 1999;42:277–341. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norhayati M, Oothuman P, Fatmah MS. Some risk factors of Ascaris and Trichuris infection in Malaysian aborigine (Orang Asli) children. Med J Malaysia. 1998;53:401–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erko B, Tedla S. Intestinal helminth infections at Zeghie, Ethiopia with emphasis on Schistosom amansoni. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1993;7:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geneva: WHO; 1986. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 8]. World Health Organization. Statistic Quarterly Reported Disease Prevention and Control; p. 39. Available from: http://www.who.int . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godkar PB, Godkar DP. Text Book of Medical Laboratory Technology. 2nd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2003. Microscopic examination of stool specimen; pp. 937–52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan MS. The global burden of intestinal nematode infections–Fifty years on. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:438–43. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merid Y, Hegazy M, Mekete G, Teklemariam S. Intestinal helminthic infection among children at Lake Awassa Area, South Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2001;1:31–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagnew M, Hailu W, Worku T, Kidane EG, Yetru S, Alene T, et al. Intensity of Intestinal parasite Infestation in a small farming village, near Lake Tana, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1993;7:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wani SA, Ahmad F, Zargar SA, Ahmad Z, Ahmad P, Tak H. Prevalence of intestinal parasites and associated risk factors among school children in Srinagar City, Kashmir, India. J Parasitol. 2007;93:1541–3. doi: 10.1645/GE-1255.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi DD, Mahendra M, Vang JM, Lee WA, Yogendra G, Minu S. Taeniasis cysticercosis situation in Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:252–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shakya SR. MD Thesis. Dharan, Nepal: B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences; 2003. Health status of primary School children in Teaching District (Dhankuta and Sunsari) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tadesse G. The prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and associated risk factors among school children in Babile town, eastern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19:140–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rai DR, Rai SK, Sharma BK, Ghimire P, Bhatta DR. Factors associated with intestinal parasitic infection among school children in a rural area of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2005;7:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisht D, Verma AK, Bharadwaj HH. Intestinal parasitic infestation among children in a semi-urban Indian population. Trop Parasitol. 2011;1:104–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.86946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celiksöz A, Güler N, Güler G, Oztop AY, Degerli S. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in three socioeconomically-different regions of Sivas, Turkey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;23:184–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awasthi S, Verma T, Kotecha PV, Venkatesh V, Joshi V, Roy S. Prevalence and risk factors associated with worm infestation in pre-school children (6-23 months) in selected blocks of Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand, India. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62:484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sah RB. MDThesis. Dharan, Nepal: BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences; 2008. A study of prevalence of Taenia infestation and associated risk factors among the school children of Dharan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashid MK, Joshi M, Joshi HS, Fatemi K. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among school going children in Bareilly District. Natl J Integr Res Med. 2011;2:35–7. [Google Scholar]