Abstract

External fistulization or subcutaneous rupture of liver echinococcal cyst (EC) is found occasionally with total of 15 cases reported in the literature. We report a case of 60-year-old female previously misdiagnosed as fistulizated osteomyelitis of the 11th rib. At computed tomography scan, non-vital EC was noted in the third liver segment. Under suspicion of external fistulization of perforated EC the patient underwent one-stage operation-pericystectomy and complete fistula excision. A retrospective analysis of the reported cases in the literature was performed with special references to classifying this rare entity. The main purpose of this report is to highlight the possibility of such a diagnosis when cutaneous fistula occurs in a same anatomic area with hydatid EC, even that cyst is proven to be calcified. We emphasize the role of a swift and radical surgical procedure including complete fistula excision to prevent secondary dissemination and post-operative complications.

KEY WORDS: Complications, cutaneous fistula, echinococcosis, surgery

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a parasitic infection caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Echinococcal cyst (EC) may develop in any organ or tissue in human body. Most often the disease affects liver (50-70%) and lungs (20-30%).[1] Patients are usually asymptomatic until incidentally diagnosed or when the complications such as cyst rupture or infection occur. EC can rupture into bile ducts, gastrointestinal tract, bronchi, peritoneal, and pleural cavity. Subcutaneous progression and/or rupture followed by external cutaneous fistula are complication rarely observed.

THE CASE

A 60-year-old female was admitted to the Department of Abdominal Surgery with complaints of abdominal pain and persistent abdominal fistula with purulent secretion. The patient had previous history of three operations for the presence of cutaneous abdominal fistula. 11-years ago rib resection of the 11th left rib was made with diagnosis of osteomyelitis. On the 5th and the 7th year, after rib resection local excisions of recurrent fistula was performed. She had also history of treated pulmonary tuberculosis – 10 years ago. At admission computed tomography (CT) was performed and it revealed a hypodense circulated mass with diameter of 5 cm [Figure 1]. The formation was located at liver segment three and it was interpreted as non-vital parasitic cyst with calcified walls and collapsed inner membrane. Other finding from CT scan was diffuse inflammatory process of abdominal wall, which correspond with the presence of external fistula. There was no evidence for the correlation between cyst and abdominal fistula especially after previous medical history for treated rib osteomyelitis, but despite that it was suspected. Physical examination revealed skin defect with purulent secretion in the area of an old surgical cicatrix at the level of the cross point of left medioclavicular line and left 11th rib. No history of fever and jaundice was present. Blood analysis and liver profile revealed no abnormalities. White blood cells count was normal. Quantiferonic tuberculosis test was negative. Serological enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay test was not performed.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showing echinococcal cyst in the left lobe of the liver and inflammatory process of abdominal, wall which correspond with the presence of fistulous tract

The patient was assessed as suitable candidate for one-stage procedure - cystectomy and fistula excision. After median laparotomy, exploration and debridement was discovered intimate attachment between echinococcal cyst and abdominal wall. Then in external fistula opening was placed a probe, which revealed communication with the cyst [Figure 2]. Before the dissection of cystic lesions (CL) cyst fluid was aspirated and hypertonic saline solution was injected into the cyst as well as the fistulous tract was irrigated. Pericystectomy and excision of the fistula tract was performed. Opening of the operative specimen revealed heterogenous degenerative contents of the cyst with calcification of its wall, but 10-12 small (0.5 mm × 0.5 mm) daughter cysts along the fistulous tract of approximately 15 cm. After an uneventful period of 6 days after surgery the patient was discharged from the unit. Post-operatively the patient underwent one course of antiparisitic therapy with albendazole 10 mg/kg. One year after surgery the patient was free of any symptoms.

Figure 2.

Probe placed through the external opening of the fistula

CONCLUSIONS

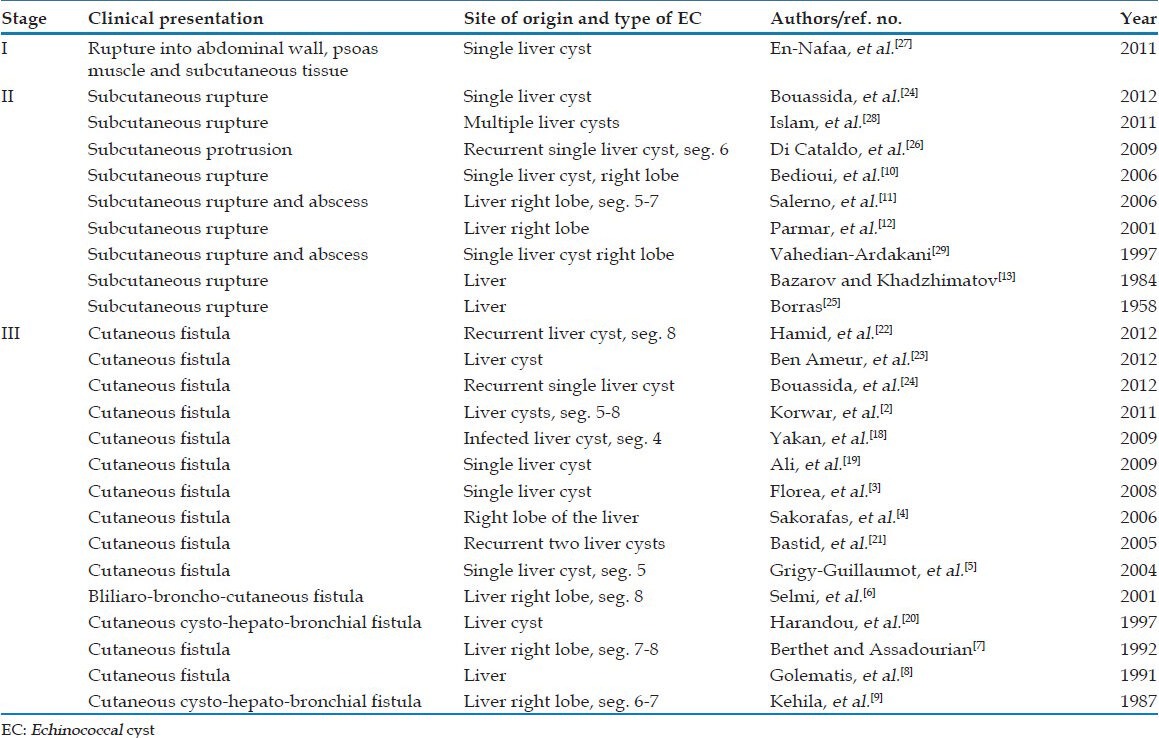

In CE infected humans are median host of the parasite's live cycle. The way of infection is alimentary. Through the gastrointestinal tract the parasite passes into the bloodstream and then by portal system it reaches the liver where it grows as cyst. E. granulosus may infest any organ, but most commonly affects the liver and the lungs. Basically liver echinococcosis is a disease with benign nature. The main problem is high rates of morbidity and recurrences. Patients with liver echinococcal cysts (LEC) may stay symptom-free for years until incidentally diagnosed or complications occurred. The main complications are rupture into the peritoneal cavity, infection, compression of the biliary tree, intrabiliary rupture, anaphylaxis, and secondary echinococcosis.[1] Cutaneous fistulization is an extremely rare complication of LEC determining the final stage of cutaneous involvement in liver echinococcosis. Recent review of the literature in this topic covers 15 previous publications whit a total of 16 reported cases in English, French, German, and Russian literature.[2] Only eight of the reviewed cases were presented as skin fistulization of LEC.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] Another four cases of LEC were resulted in subcutaneous rupture without fistula of the skin,[10,11,12,13] in three cases cutaneous involvement was due to alveolar echinococcosis,[14,15,16] and one case illustrated skin involvement of EC of the spleen.[17] To the best of our knowledge, the total number of reported cases concerning skin fistulization in liver echinococcosis is 15.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] Two of them are cutaneous-cysto-bronchial fistulization of LEC[9,20] and single report describes communication of LEC with the skin and the biliary tract and bronchi.[6] We found six additional case reports for subcutaneous rupture of EC without skin fistula opening.[24,25,26,27,28,29] There are also single case report about spontaneous cyst-cutaneous fistula caused by pulmonary EC,[30] one case report about EC of the rib with cutaneous fistulization[31] and two reported cases of subcutaneous extension of diaphragmatic EC.[32,33] The case we presented is 16th in the world literature describing skin fistulization in LEC and it is first in our country. It is our opinion that this rare condition could be defined as last stage of parietal complication of some form of liver echinococcosis. Depending on the time of diagnosis and/or treatment, cyst may protrude into abdominal wall in each of its layers – muscles (Stage I), subcutaneous tissue (Stage II), and formation of skin fistula (Stage III). The collected data from the literature is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parietal complications of liver echinococcal cysts

Involvement of the abdominal wall in LEC is still unknown. The progressive growth of the cysts, their tendency to erode the organs and tissues with which they come into contact, and their infection could explain the unusual evolution of some of the cysts located in the liver margins. The damaging effect of the cyst on the abdominal wall progresses with time, developing from close adherence to penetration through the muscles, subcutaneous rupture and/or fistula formation. Usually, cysts originating from the right hepatic lobe invade the right lateral abdominal wall or cysts from the left lobe invade the anterior abdominal wall. Cyst usually passes through small orifice adopting an “hourglass configuration.”[12,26] Spontaneous skin fistulization is possible and has been described.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] Lewall and McCorkell had classified the rupture of LEC into three categories: Contained, communicating, and direct.[34] Contained rupture occurs when only the endocyst ruptures and the cyst contents remain confined to the intact pericyst. Endocyst detachment is seen at cross-sectional imaging as floating membrane within the cyst. Communicating rupture consists of a rupture of the endocyst with the escape of cyst contents into bronchioles or biliary radicals that are incorporated into the pericyst. Direct rupture is when both the endocyst and pericyst tear, causing a leakage of contents into the pleural or peritoneal cavities or other adjacent tissues and may cause various complications that is anaphylactic shock, secondary bacterial infection.

Moreover, in the majority of cases suppuration precedes rupture. Because of increasing intracystic tension with the onset of suppuration and the direct destruction of tissue by this process, all layers rupture and fistulization takes place. The complete rupture reduces the turgor of the cyst, which then decreases in size or collapses.

The challenge in our case laid in its clinical presentation. At the most sensitive means of diagnosing cyst rupture - CT scan, a collapse of the cyst inner membrane was observed as well as cyst perforation and cysto-cutaneous fistula formation. Thus, our case should be classified as direct rupture of LEC.

Recent progress in our knowledge regarding CE led to development and introducing the standardized ultrasound classification proposed by World Health Organization-Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (World Health Organization Informal Working Groups on Echinococcosis [WHO-IWGE]).[1] According to this classification based on sonographic analysis of the morphology and structure of the hydatid cysts five categories are recognized. This classification reflects the functional state of the parasite that facilitates selection of treatment modalities. Types CL, CE1, and CE2 represent the active cysts; types CE4 and CE5 are suggestive of inactive cysts; type CE3, transitional, starting to degenerate cyst. The proposal of a consensus WHO classification by the IWGE is a major step forward; its wide application should allow standardization of treatment indications and their evaluation in the future. Unfortunately, as in our case, when the complication of the cyst still developed, morphology and structure of the cyst did not reflect the functional state of the parasite. We found cyst of type CE4, but fistulous tract with more than 10 viable daughter cysts.

In general, the majority of classifications of CE are based on imaging features. Proposed by us TN(R)C classification for LEC is a comprehensive system based on four criteria: Topographic location (T), natural history (N), recurrence (R) and complications (C) of the cyst.[35] The TN(R)C classification system is optimally descriptive and is very important and useful for our institutional data comparison and permits extensive statistical analysis. According to this classification, our case was classified as T3N4R0C6 (six points or clinical staging of Grade 2)[36] as grade of the cyst reflects the grade of the complication. We agree that different forms of hydatid liver cysts should be evaluated separately.[37] Moreover, this case presenting one of the 18-25% reported complicated cases of LEC in the literature that are not suitable to classify by any other classification system. It is not possible to conclude from the present case that the classification described is better than those proposed by WHO; only a randomized, controlled trial would resolve this issue. We are aware of the limitations and potential biases of a descriptive design related to evidence-based medical practice. As a rule, an uncommon manifestation of LEC makes the carrying out of other methodological designs more difficult because of the limited number of cases.

The difficulties with diagnosis and the severe progress of the disease render complicated liver EC of special clinical interest. The appropriate treatment is determined by several factors; however, surgery is clearly indicated in cysts of any type that have any form of complication. Complete resection of the cyst along with the fistulous tract was feasible for our patient with a familiar procedure - fistulectomy, without any unexpected difficulties encountered during the operation.

The infrequency of EC fistulization may lead to misdiagnosis. The main purpose of this report is to highlight the possibility of such a diagnosis when cutaneous fistula occurs in a same anatomic area with EC even that cyst is proven to be calcified. Moreover, we emphasize the role of a swift and the radical surgical procedure including complete fistula excision to prevent the secondary dissemination and post-operative complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korwar V, Subhas G, Gaddikeri P, Shivaswamy BS. Hydatid disease presenting as cutaneous fistula: Review of a rare clinical presentation. Int Surg. 2011;96:69–73. doi: 10.9738/1364.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florea M, Barbu ST, Crisan M, Silaghi H, Butnaru A, Lupsor M. Spontaneous external fistula of a hydatid liver cyst in a diabetic patient. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2008;103:695–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakorafas GH, Stafyla V, Kassaras G. Spontaneous cyst-cutaneous fistula: An extremely rare presentation of hydatid liver cyst. Am J Surg. 2006;192:205–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grigy-Guillaumot C, Yzet T, Flamant M, Bartoli E, Lagarde V, Brazier F, et al. Cutaneous fistulization of a liver hydatid cyst. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:819–20. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selmi M, Kharrat MM, Larbi N, Mosbah M, Ben Salah K. Communication of an hydatid cyst of the liver with the skin and the biliary tract and bronchi. Ann Chir. 2001;126:595–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(01)00559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthet B, Assadourian R. Hydatid cyst of the liver disclosed by metastatic subcutaneous localization. Presse Med. 1992;21:952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golematis BC, Karkanias GG, Sakorafas GH, Panoussopoulos D. Cutaneous fistula of hydatid cyst of the liver. J Chir (Paris) 1991;128:439–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehila M, Allègue M, Abdesslem M, Letaief R, Saïd R, Ben Hadj Hamida R, et al. Spontaneous cutaneous-cystic-hepatic-bronchial fistula due to an hydatid cyst. Tunis Med. 1987;65:267–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedioui H, Ayadi S, Nouira K, Bakhtri M, Jouini M, Ftériche E, et al. Subcutaneous rupture of hydatid cyst of liver: Dealing with a rare observation. Med Trop (Mars) 2006;66:488–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salerno S, Cracolici E, Lo Casto A. Subcutaneous rupture of hepatic hydatid cyst: CT findings. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:619–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parmar H, Nagarajan G, Supe A. Subcutaneous rupture of hepatic hydatid cyst. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:870–2. doi: 10.1080/00365540110027286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazarov AKh, Khadzhimatov G. Echinococcosis of subcutaneous fatty tissue. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 1984;133:80–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambo M, Adachi K, Ohkawara A. Postoperative alveolar hydatid disease with cutaneous-subcutaneous involvement. J Dermatol. 1999;26:343–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb03485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bresson-Hadni S, Humbert P, Paintaud G, Auer H, Lenys D, Laurent R, et al. Skin localization of alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:873–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschudi K, Ammann R. Recurrent chest wall abscess. Result of a probable percutaneous infection with Echinococcus multilocularis following a dormouse bite. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1988;118:1011–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kismet K, Ozcan AH, Sabuncuoglu MZ, Gencay C, Kilicoglu B, Turan C, et al. A rare case: Spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid cyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2633–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yakan S, Yildirim M, Coker A. Spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected liver hydatid cyst. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2009;20:299–300. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2009.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali AA, Sall I, El Kaoui H, Zentar A, Sair K. Cutaneous fistula of a liver hydatid cyst. Presse Med. 2009;38:e27–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harandou M, el Idrissi F, Alaziz S, Cherkaoui M, Halhal A. Spontaneous cutaneous cysto-hepato-bronchial fistula caused by a hydatid cyst. Apropos of a case. J Chir (Paris) 1997;134:31–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastid C, Pirro N, Sahel J. Cutaneous fistulation of a liver hydatid cyst. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:748–9. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)88218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamid R, Shera AH, Bhat NA, Baba AA, Rashid A, Akhter A. Hydatid cyst of liver: Spontaneous rupture and cystocutaneous fistula formation in a child. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2012;17:73–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.93968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben Ameur H, Trigui A, Boujelbène S, Beyrouti MI. Cutaneous fistula due to hydatid cyst of the liver. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139:292–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouassida M, Sassi S, Mighri MM, Laajili A, Chebbi F, Chtourou MF, et al. Parietal complications of hydatid cyst of the liver. Report of two cases in Tunisia. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2012;105:259–61. doi: 10.1007/s13149-012-0224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borras JA. Subcutaneous rupture of a hydatid cyst of the liver. Med Esp. 1958;40:344–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Cataldo A, Latino R, Cocuzza A, Li Destri G. Unexplainable development of a hydatid cyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3309–11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.En-Nafaa I, Moujahid M, Alahyane A, Amil T, Hanine A, Ziadi T. Hydatid cyst of the liver ruptured into the abdominal wall and the psoas muscle: Report of a rare observation. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;10:3. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v10i0.72207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam MN, Khan NA, Haque SS, Hossain M, Ahad MA. Hepatic hydatid cyst presenting as cutaneous abscess. Mymensingh Med J. 2012;21:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vahedian-Ardakani J. Hydatid cyst of the liver presenting as cutaneous abscesses. Ann Saudi Med. 1997;17:235–6. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1997.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onat S, Avci A, Ulku R, Ozcelik C. Spontaneous cyst-cutaneous fistula caused by pulmonary hydatid cyst: An extremely rare case. Dicle Tip Derg. 2008;35:280. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chafik A, Benjelloun A, El Khadir A, El Barni R, Achour A, Ait Benasser MA. Hydatid cyst of the rib: A new case and review of the literature. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:817205. doi: 10.1155/2009/817205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinis A, Fragulidis G, Karapanos K, Konstantinidis C, Brestas P, Vassiliou J, et al. Subcutaneous extension of a large diaphragmatic hydatid cyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7210–2. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gümüş M, Yağmur Y, Gümüş H, Kapan M, Onder A, Böyük A. Primary hydatid disease of diaphragm with subcutenous extension. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:599–602. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewall DB, McCorkell SJ. Rupture of echinococcal cysts: Diagnosis, classification, and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:391–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kjossev KT, Losanoff JE. Classification of hydatid liver cysts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:352–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kjossev K, Belokonski E, Vladov N. Monduzzi Editore. France: Proceedings of 44th Congress of the European Society for Surgical Research Nîmes; 2009. May 20-23, TN (R) C points system for cystic echinococcosis: Clinical evaluating and monitoring of the disease; pp. 61–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kayaalp C. Hydatid disease of the liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:331. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]