Abstract

PURPOSE

In addition to bone mineral density (BMD), trabecular microstructure contributes to skeletal strength. Our goal was to examine changes in trabecular microstructure in women on therapy.

MATERIALS and METHODS

We followed 10 postmenopausal women receiving a bisphosphonate, risedronate (35 mg once weekly), over 12 months and examined trabecular microarchitecture with high resolution wrist MR images (hr-MRI). MRI parameters included bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), surface density (representing plates), curve density (representing rods), surface-to-curve ratio and erosion index (depicting deterioration). We assessed BMD of the spine, hip and radius and markers of bone turnover.

RESULTS

Women had been receiving bisphosphonate therapy for 43 ± 9 months (mean ± SD) prior to the first MRI. Indices of hr-MRI demonstrated improvement in surface-to-curve ratio (13.0 %) and a decrease in erosion index (12.1 %) consistent with less deterioration (both p<0.05). BMD of the spine, hip and radius and markers of bone turnover remained stable. Parameters of hr-MRI were associated with 1/3 distal radius BMD (correlation coefficient 0.71 to 0.86, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

We conclude hr-MRI of the radius demonstrates improvements in trabecular microstructure not appreciated by conventional BMD and provides additional information on parameters that contribute to structural integrity in patients on antiresorptive therapy.

Key Terms: trabecular microarchitecture, high resolution MRI, bisphosphonate therapy, osteoporosis

INTRODUCTION

Bone mineral density (BMD) by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is considered the gold standard, non-invasive method to assess risk of future fracture and help classify postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (1,2). However, BMD may only account for 30% of reduction in fracture risk following therapy (3–5). Other factors thought to be important include trabecular structure, cortical porosity, bone turnover and mineralization (3,6).

Previous studies that have examined bone architecture have focused on conventional 2-D histomorphometry from iliac crest bone biopsy specimens from patients. More recently, investigators have used 3-D microcomputed tomography. Borah and colleagues reported that women treated with risedronate for 3 years had maintenance of trabecular architecture assessed by iliac crest biopsies and 3-D qCT, compared to women on placebo who had deterioration with a change from plate like structures to rods (7). However, the variability of serial biopsies is high because the same site cannot be measured twice. A technique that allows follow-up measurement of the same site multiple times would be a significant advantage to examine architectural changes over time. Furthermore a noninvasive technique would be a significant advance over an invasive bone biopsy for patients. Finally a techniques such as MRI that does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation would also be an advantage over imaging that uses conventional x-rays or CT.

A technique known as high resolution MRI (hr-MRI) of the radius provides a three-dimensional image of bone trabecular microarchitecture (8–10), and has emerged as a method for performing in vivo morphometry in a noninvasive manner. Wehrli and colleagues examined 79 women age 28–78 years (mean age of 54) with hr-MRI and an assessment for vertebral fractures. Although there were no differences in the standard BMD by DXA at the spine, femoral neck or trochanter between women with a vertebral fracture and those without, they reported significant differences in the topographical microarchitecture indices assessed by hr-MRI. Those with vertebral fractures had a lower ratio of plate-like to rod-like trabecular than those without fracture. The number of intact trabecular rods was also lower in the vertebral fracture group (9). The goal of this investigation was to use the technique of hr-MRI to examine changes in microarchitecture parameters in patients on bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis. We postulated bisphosphonate therapy would demonstrate a stable conventional BMD with no loss, while hr-MRI might demonstrate changes in trabecular microarchitecture not observed with conventional modalities. We also hypothesized that baseline parameters in standard radial bone mineral density would be associated with indices of radial hr-MRI.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study Design

This was an open-label, non-randomized, pilot study in elderly women with osteoporosis to examine changes in indices of trabecular microarchitecture assessed by hr-MRI technology over one year (baseline and 12 months) in ten patients on risedronate. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh approved this study and patients provided written informed consent.

Subjects

We included postmenopausal women age 60 or older with a clinical or DXA diagnosis of osteoporosis (made by their physician) who were being treated with risedronate 35 mg po once weekly. The patients were selected sequentially and included patients of the authors and patients from the endocrinology practice at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Subjects were excluded if they were currently on other osteoporosis therapy. If they had previously been on other antiresorptive agents and switched due to an adverse event, they were allowed to participate as long as they were on risedronate for at least one month prior to enrollment. We excluded patients who were treated with fluoride, strontium, or if patients had previously been on teriparatide. We excluded patients with other disorders of bone mineral metabolism, if they were currently on glucocorticoids and anticonvulsants, or if they previously had a right wrist fracture.

Outcomes

High Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging

High resolution magnetic resonance imaging (hr-MRI) uses a patented algorithm that transforms data into a highly detailed three-dimensional model of bone microstructure as previously described (11). A coil assesses the right distal forearm using the GE Signa 1.5 Tesla scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA). The technique permits quantification of the degree to which trabecular plates (surfaces) have deteriorated to become rods (curves), a change that characterizes osteoporosis (9). Using the unique algorithm, each image voxel can be classified as belonging to a surface or curve or junction between the two fundamental topological types. Similarly, an erosion index is determined that represents the ratio of voxels expected to decrease during resorptive bone loss divided by those that are expected to increase. The volume acquired for trabecular measurements consists of 32 slices (24 of which are typically included in the ROI) with voxel size of 137 × 137 × 410 μm. The topological parameters (e.g., plate-to-rod ratio and erosion index) are computed after the resolution has been enhanced by the software, resulting in a voxel size of approximately 67 μm isotropic. The software places the ROI automatically. A seed point is automatically selected in the trabecular/bone marrow region inside the cortical shell, and then a connected ROI is grown around the seed based on intensity and shape considerations. The outer boundary of the ROI is typically within 1mm of the cortical endosteal boundary. The user is given the opportunity to view and, if needed, manually modify the ROI boundary on individual slices before additional processing and the measurements are performed. The indices include the bone volume to total volume ratio (BV/TV), the topological surface density (surface density), the topological curve density (curve density), the surface-to-curve ratio where higher values indicate a more intact trabecular network and lower values indicate a network that has deteriorated; and an erosion index, a ratio of parameters expected to increase when bone trabeculae deteriorate, where higher values indicate greater deterioration. For comparison purposes, qCT reports a Structure Model Index which is an estimation of plate or rod-like nature of trabecular bone (7). The reproducibility of measurements for hr-MRI ranges from 4 to 9% and the reliability expressed is the interclass correlation coefficient ranges from 0.95 to 0.97 at the radius (12).

Bone Mineral Density and Bone Turnover Markers: Bone mineral density of the PA spine (L1–L4), lateral spine (L1–L3), hip (total hip, femoral neck), and right radius (1/3 distal radius, ultra distal radius, total radius) was performed by DXA using a Hologic Discovery A (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA). We collected serum for a marker of bone formation, aminoterminal propeptide of type I collagen (P1NP, μg/L, Orion Diagnostica, Inc) and bone resorption, serum C-telopeptide of collagen cross-links (CTX, nmol/L BCE, Crosslaps, Osteometer Biotech) and collected morning urine for N-telopeptide of collagen cross-links (uNTX nmol bone collagen equivalents/mmol creatinine, Osteomark, Ostex International).

Statistical Analysis

SAS® version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for all statistical analyses. We used descriptive statistics and graphical methods to summarize baseline, 12-month, and baseline to 12-month change in all measures. We used paired samples t-tests to compare baseline measures to 12-month follow-up measures and obtain statistical significance of change. We used Pearson correlation coefficients to examine the associations among baseline BMD, biomarkers and hr-MRI measures; associations among baseline to follow-up changes in BMD, biomarkers and hr-MRI measures; and associations of prior treatment duration with baseline and baseline to follow-up changes in BMD, biomarkers and hr-MRI measures. Robustness of the results was examined by using both raw and percent change of the measures in the analyses.

RESULTS

At baseline, subjects were an average age of 71.3 ± 3.1 (mean ± SD) years and had been on antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis for 43 ± 9 months. Three women had been on alendronate prior to risedronate therapy. Prior to the study, they were switched to risedronate by their physician. Two switched due to gastrointestinal adverse events and one patient had a decrease in bone density. The mean T-score was −2.0 SD in the spine, −1.8 SD in the total hip, −2.4 SD in the femoral neck and −2.3 SD in the 1/3 distal radius. Women had a mean level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D of 27.6 ± 4.1 ng/mL.

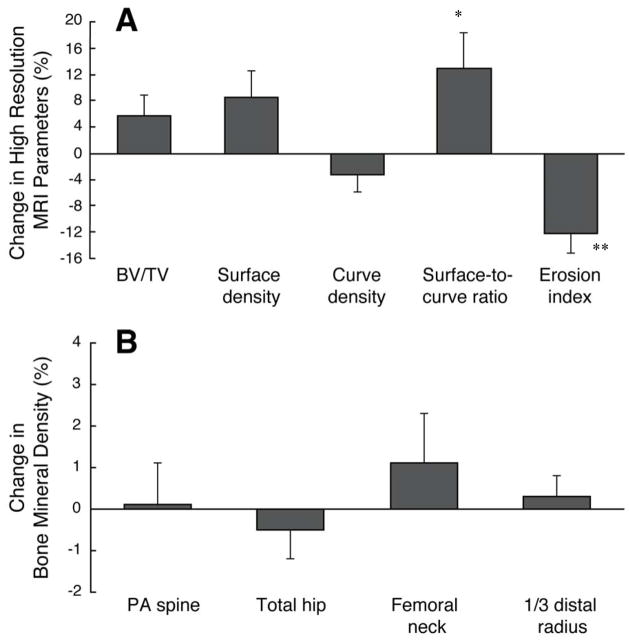

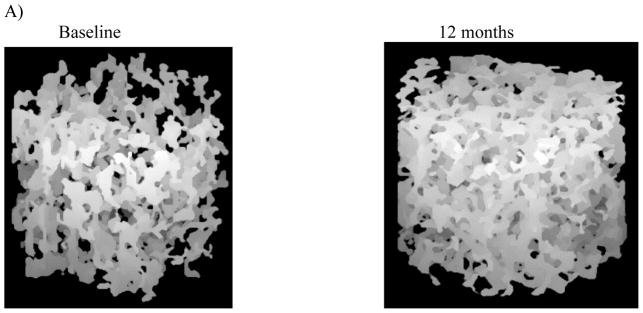

After 12 months of therapy, the women receiving risedronate had improvement in the hr-MRI derived topological parameters (Table 1 and Figure 1). There was a significant increase of 13.0 ± 5.4% (p<0.05) in the surface-to-curve ratio and a significant decrease of 12.1 ± 3.1% (p<0.01) in the erosion index. There was also a trend for a significant improvement of 8.6 ± 4.1% in surface density (p=0.062). A representative image from a patient on risedronate at baseline and 12 months is shown in figure 2. Women had no significant changes in bone mineral density of the PA spine, lateral spine, total hip, femoral neck or any radial sites including the 1/3 distal radius, total radius and ultradistal radius (Figure 1). Furthermore, the markers of bone resorption and formation remained stable without change (Table 1).

Table 1.

Absolute Changes in hr-MRI Parameters and Bone Turnover Markers over 12 Months

| Mean Value | Baseline to 12 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 Months | Absolute Change | P value | |

| MicroMRI topological parameters | ||||

| BV/TV (%) | 0.106 ± 0.004 | 0.111 ± 0.002 | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 0.106 |

| Surface density | 0.043 ± 0.007 | 0.047 ± 0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.074 |

| Curve density | 0.011 ± 0.000 | 0.010 ± 0.000 | −0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.233 |

| Surface-to-curve ratio | 4.067 ± 0.227 | 4.540 ± 0.222 | 0.474 ± 0.196 | 0.036 |

| Erosion index | 1.728 ± 0.068 | 1.508 ± 0.054 | −0.220 ± 0.060 | 0.005 |

| Bone turnover markers | ||||

| P1NP (μg/L) | 29.5 ± 5.1 | 25.6 ± 3.6 | −3.9 ± 2.6 | 0.162 |

| CTX (nmol/L BCE) | 0.329 ± 0.058 | 0.294 ± 0.027 | −0.035 ± 0.044 | 0.447 |

| uNTX (nmol BCE/mmol Cr) | 24.4 ± 4.0 | 23.7 ± 3.1 | −0.7 ± 2.3 | 0.772 |

Figure 1.

Panel A: Percent changes over 12 months in hr-MRI parameters in patients on risedronate, hr-MRI = high resolution MRI, BV/TV=bone volume/total volume.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 from baseline

Panel B: Percent change over 12 months in bone mineral density in patients on risedronate.

Figure 2.

High resolution hr-MRI images of representative at baseline and 12 months of treatment in a patient on risedronate. The patient had a change of 19.2 % in the surface-to-curve ratio and −13.0 % in the erosion index.

There were significant associations between the baseline radial bone mineral density and the hr-MRI derived topological parameters. The strongest associations were observed between the 1/3 distal radius BMD and BV/TV (r=0.85, p<0.01), surface density (r=0.86, p<0.01), surface-to-curve ratio (r=0.71, p<0.05) and erosion index (r=−0.65, p<0.05). The associations with the total radius and ultra distal radius for BV/TV and surface-to-curve ratio were also statistically significant (total radius r range 0.63–0.85, ultra distal radius r range 0.74–0.82, all p<0.05). There were no significant associations between the hr-MRI derived parameters and PA spine, total hip or femoral neck BMD. There were no significant associations between baseline levels of turnover markers and the hr-MRI parameters. There were no associations between the duration of bisphosphonate therapy and the changes in the hr-MRI parameters.

DISCUSSION

Despite no significant changes in areal bone mineral density of the radius, hip or spine sites or markers of bone turnover with the antiresorptive risedronate, indices of radial hr-MRI demonstrated improvement in trabecular bone with an increase of the surface-to-curve ratio and a decrease in the erosion index consistent with less deterioration. Previous studies have examined hr-MRI parameters in patients on antiresorptive therapy. Wehrli and colleagues followed distal tibia hr-MRI in 32 women on estradiol therapy for 24 months (13). They reported a 6.9% increase in BV/TV, a 7.8% increase in surface density (both p<0.05) and an 8.6% increase in surface-to-curve ratio (p=0.07), despite no significant changes in conventional hip or spine BMD. The mechanism for the improvement in the hr-parameters with antiresorptive therapy is not apparent. However, Heaney has postulated an anabolic effect from alendronate to explain differences between improvement in BMD and remodeling transients (14). Furthermore we have previously reported a nocturnal increase in parathyroid hormone levels in patients after 1 year on alendronate therapy despite reductions in markers of bone formation including bone-specific alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin (15). Additional studies are needed to investigate the improvement in trabecular microstructure with antiresorptive therapy.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the increase in BMD resulting from antiresorptive therapy decreases over time and may reach a plateau over 3–5 years (16). Similarly, biochemical markers of bone remodeling decrease rapidly (6 months) after therapy is initiated and remain stable thereafter (17). It has been speculated that in some patients this suppression of bone remodeling may represent a state of near total arrest. There are reports of patients experiencing unusual minimal trauma fractures in whom dynamic histomorphometry displays an almost total absence of remodeling (18, 19, 20). Direct comparisons of the topologic parameters of hr-MRI with dynamic histomorphometry have not been performed. However the significant decrease in erosion index in our subjects, in the absence of change in either BMD or markers of bone remodeling, suggests that remodeling is still ongoing. If this is confirmed in other studies, hr-MRI may provide a useful non-invasive method of monitoring the ongoing improvement in the skeleton beyond that seen with either DXA or biochemical markers.

Although we did not find an association with conventional DXA-based BMD of the PA spine or hip, we found a strong association between conventional DXA of the radius and the radial hr-MRI parameters. This association has not been previously reported. The findings at the forearm are of particular interest because changes at the radius following several years of bisphosphonate therapy are minimal compared to changes often observed at the spine and hip sites (21). However, despite the minimal improvements in radial BMD, significant reductions in wrist fractures have been reported in trials with oral bisphosphonate (21). These data, demonstrating improvements in trabecular connectivity by microMRI, provide support for the hypothesis that additional factors contribute to fracture reduction that are not explained by conventional DXA-derived BMD.

There are several strengths of this study. This is the first study to use this type of high resolution MRI to examine antiresorptive therapy with a once weekly oral bisphosphonate. In addition, we examined the association of areal bone mineral density of the wrist with the hr-MRI indices of the wrist. Moreover, we examined association of bone turnover markers with these indices. However, there are several limitations with this study. There was no control group and patients were placed on medication by their physician. Secondly, the sample size was small. However, other studies have shown significant decreases or maintenance of these parameters with similar sample size (22). Furthermore, the duration of therapy was 12 months. In addition, the contribution of change in mineralization is not known. However, bisphosphonate therapy increases the degree of mineralization which may contribute to changes observed with standard DXA early in therapy. These patients had already been on bisphosphonate therapy for a mean of 43 months, so it is less likely that a change in mineralization contributed to the observed changes in architecture. Finally we only examined the impact of one bisphosphonate over 12 months and these findings may not be generalizable to all bisphosphonates.

In summary, we found that despite maintenance of bone density with the antiresorptive bisphosphonate risedronate, in women who had been on therapy for several years, the indices of trabecular microarchitecture improved. These data support the postulate that improvements in microstructure that are not appreciated by conventional DXA-derived BMD may contribute to fracture reduction. The increase in surface-to-curve ratio and a decrease in deterioration support the previous findings in the large pivotal trials suggesting a decrease in nonvertebral fractures including wrist fractures with risedronate over several years (23). Future studies are needed that examine longer duration of antiresorptive therapy and the association of fracture reduction with changes in hr-MRI indices.

Acknowledgments

K24 to Dr. Greenspan (K24 DK062895-01), The University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC- Ul1 RR024153), Pepper Center Grant (P30 AG024827, Greenspan- Core PI)

Contributor Information

Subashan Perera, Email: PereraS@dom.pitt.edu.

Robert Recker, Email: RRecker@creighton.edu.

Julie M. Wagner, Email: wagnerj@dom.pitt.edu.

Parmatma Greeley, Email: greeleyps@gmail.com.

Bryon R. Gomberg, Email: BGomberg@micromri.com.

Pamela Seaman, Email: PSeaman@micromri.com.

Michael Kleerekoper, Email: MKleerekoper@micromri.com.

Reference List

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinicians Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporsis. Washington, DC: Copyright NOF; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouxsein ML. Mechanisms of osteoporosis therapy: a bone strength perspective. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;2:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochberg MC, Greenspan S, Wasnich RD, Miller P, Thompson DE, Ross PD. Changes in bone density and turnover explain the reductions in incidence of nonvertebral fractures that occur during treatment with antiresorptive agents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1586–1592. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Harris F, Genant HK, Ensrud K, LaCroix AZ, Black DM. Improvement in spine bone density and reduction in risk of vertebral fractures during treatment with antiresorptive drugs. Am J Med. 2002;112:281–289. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seeman E. Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet. 2002;359:1841–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borah B, Dufresne E, Chmielewski PA, Johnson TD, Chines A, Manhart MD. Risedronate preserves bone architecture in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis as measured by three-dimensional microcomputed tomography. Bone. 2004;34:736–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wehrli FW, Saha PK, Gomberg BR, Song HK, Snyder PJ, Benito M, Wright A, Weening R. Role of magnetic resonance for assessing structure and function of trabecular bone. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;13(5):335–356. doi: 10.1097/00002142-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehrli FW, Gomberg BR, Saha PK, Song HK, Hwang SN, Snyder PJ. Digital topological analysis of in vivo magnetic resonance microimages of trabecular bone reveals structural implications of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1520–1531. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehrli FW. Structural and functional assessment of trabecular and cortical bone by micro magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:390–409. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wehrli FW, Hwang SN, Ma J, Song HK, Ford JC, Haddad JG. Cancellous bone volume and structure in the forearm: noninvasive assessment with MR microimaging and image processing. Radiology. 1998;206:347–357. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.2.9457185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ladinsky GA, Vasilic B, Popescu AM, Wald M, Zemel BS, Snyder PJ, Loh L, Song HK, Saha PK, Wright AC, Wehrli FW. Trabecular Structure Quantified with the MRI-Based Virtual Bone Biopsy in Postmenopausal Women Contributes to Vertebral Deformity Burden Independet of Areal Vertebral BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:64–74. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.070815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehrli FW, Ladinsky GA, Jones C, Benito M, Magland J, Vasilic B, Popescu AM, Zemel B, Cucchiara AJ, Wright AC, Song HK, Saha PK, Peachey H, Snyder PJ. In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Detects Rapid Remodeling Changes in the Topology of the Trabecular Bone Network After Menopause and the Protective Effect of Estradiol. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:730–740. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heaney RP, Yates AJ, Santora AC., II Bisphosphonate effects and the bone remodeling transient. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1143–1151. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenspan SL, Holland S, Maitland-Ramsey L, Poku M, Freeman A, Yuan W, Kher U, Gertz B. Alendronate stimulation of nocturnal parathyroid hormone secretion: a mechanism to explain the continued improvement in bone mineral density accompanying alendronate therapy. Proc Assoc Am Phys. 1996;108:230–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer J-P, Tucci JR, Emkey RD, Tonino RP, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Downs RW, Gupta J, Santora AC, Liberman UA. Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnick S, Saag KG, Kiel DP, McClung M, Hochberg M, Burnett S-AM, Sebba A, Kagan R, Chen E, Thompson DE, de Papp AEftFACTFi. Comparison of weekly treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with alendronate versus risedronate over two years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2631–2637. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visekruna M, Wilson D, McKiernan FE. Severly suppressed bone turnover and atypical skeletal fragility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2948–2952. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh SK, Yang KY, Koh JSB, Wong MK, Chua SY, Chua DTC, Howe TS. Subtrochanteric insufficiency fractures in patients on alendronate therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(3):349–353. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ing-Lorenzini K, Desmeules J, Plachta O, Suva D, Dayer P, Peter R. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with the long-term use of bisphosphonates: a case series from a Swiss university hospital. Drug Safety. 2009;32(9):775–785. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benito M, Vasilic B, Wehrli FW, Bunker B, Wald M, Gomberg B, Wright AC, Zemel B, Cucchiara A, Snyder PJ. Effect of Testosterone Replacement on Trabecular Architecture in Hypogonadal Men. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1785–1795. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH, III, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD for the Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]