Abstract

Background

Terminally ill patients with lower incomes are less likely to die at home, even with hospice care.

Methods

Analysis of VITAS hospice patients admitted to routine care in a private residence between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2003. We matched zip codes to U.S. census tracts to generate annual median household incomes and divided the measure into $10,000 increments from ≤$20,000 to >$50,000). To examine the relationship between income and transfer from home before death, we used logistic regression (adjusted for demographics, diagnosis, region, length of stay). We also examined the interaction between income and level of hospice care (any vs. no continuous care) as a predictor of transfer from home. Unlike routine care which includes periodic visits by hospice, continuous care is a higher level of care, used for short periods of crisis to keep a patient at home and includes hospice services in the home at least 8 hours in a 24 hour period.

Results

Of the 61,063 enrollees admitted to routine care in a private residence, 13,804 (22.6%) transferred from home to another location (i.e. inpatient hospice unit, nursing home) with hospice care before death. Patients who transferred had a lower average median household income ($42,585 vs. $46,777, P<0.001) and were less likely to have received any continuous care (49.38% vs. 30.61%, P<0.001). The median number of days of continuous care was 4. For patients who did not receive continuous care, the odds of transfer from home before death increased with decreasing annual median household incomes (OR range 1.26—1.76). For patients who received continuous care, income was not a predictor of transfer from home.

Conclusions

Patients with limited resources may be less likely to die at home, especially if they are not able to access needed support beyond what is available with routine hospice care.

Introduction

Most Americans report wanting to die at home.1,2 However, despite these preferences and better outcomes for care at home compared to other settings, in 2007, only 30% of decedents under age 65 and 24% of decedents 65 or older died at home.3-6 Even when patients want to die at home, lack of caregiver support,7 lack of healthcare provider knowledge of preferences,1 and poor symptom control8 may result in transfer to sub-acute or acute care settings prior to death.9,10

Some patients face additional challenges in dying at home. For example, compared to wealthier patients, those with lower incomes are less likely to die at home7,8 due to poorer access to healthcare, less knowledge of resources, less communication with providers about care preferences, lack of resources to assist with caregiving, and greater symptom burden at the end of life.3,11,12 Additionally, those with lower incomes are less likely to enroll in hospice, which facilitates dying at home.13,14 In 2003, approximately 50% of hospice enrollees died at home compared to 25% in the general population.15 By providing an interdisciplinary team of healthcare professionals for symptom management, personal care, psychosocial and emotional support, and medications and equipment related to the terminal illness, hospice may help decrease some barriers to dying at home for those with limited resources.16,17

Of importance for indigent patients, the standard hospice benefit is defined for the majority of patients by Medicare or Medicaid, and most hospices provide unreimbursed care for those without coverage. Private insurance plans generally provide similar benefits.18,19 Hospice staff are available 24 hours a day,8 including, when needed, providing continuous care in the home to treat symptoms not easily managed with routine hospice care. While routine hospice care consists primarily of periodic home visits by staff, continuous care is a short-term intense period of care which includes the presence of hospice staff providing care for a minimum of 8 hours in a 24-hour period, with at least half provided by a nurse. Continuous care helps patients stay in their homes by providing the care they might otherwise seek in acute care settings.

Many studies have evaluated factors associated with location of death,20-23 as well as healthcare use and place of death among patients who disenroll from hospice.24-26 However, the association of income and/or the intensity of care provided by hospice with transfer from home to another location prior to death among those continuing to receive hospice care remains largely unexplored. The purpose of this study was to examine in a large cohort of patients who continued to receive hospice care until death the association between income and transfer from home to another location, and how this association differs based on the intensity of care provided by hospice (any continuous care vs. no continuous care). Understanding the association of income and intensity of hospice care with transfer from home to another location may provide information about the type of services, beyond those currently available as part of the hospice program, which patients with lower incomes may need to die in the location of their preference.

Methods

Data Source

Data were obtained from VITAS Healthcare, a for-profit hospice provider. For the period of these analyses, VITAS operated 26 hospice programs in eight states (Florida, Illinois, Ohio, California, Texas, Wisconsin, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania). After approval from the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board and VITAS Healthcare, data were abstracted from VITAS' central administrative and clinical database.

Study Population

We included hospice enrollees who were admitted to routine home hospice care, resided in a private residence at the time of admission, and who died between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2003. We excluded one patient missing location of death, 220 lacking median household income (due to missing zip codes), 337 without caregiver information, and 2 without admission diagnoses. The final sample included 61,063 hospice enrollees.

Outcome

The primary outcome was transfer from hospice care in a private residence to hospice care in a site outside the home prior to death. We defined a transfer as any enrollee with a location of death other than a private residence, including assisted living facility, nursing home, hospital, or inpatient hospice setting. We dichotomized the primary outcome variable as no transfer (remained home until death) versus transfer (transferred to any location outside the home prior to death).

Predictor Variable

The predictor of interest was median household income. Because the database did not include the income of individual enrollees, we obtained median household income by matching enrollees' zip codes to US Census tract data from 2000. This method has been used in other research.27,28 We categorized median annual household income as follows: $0-$20,000, >$20,000-$30,000, >$30,000-$40,000, >$40,000-$50,000, >$50,000. Since our focus was resource limitations, incomes above the US median household income were consolidated into one category (>$50,000). Due to limited subjects in zip codes with median annual incomes ≤$10,000, we combined them to form one group with incomes ≤$20,000.

Because we wanted to determine if the relationship between income and transfer from home to another location prior to death was different based on level of hospice care provided, we created an interaction term-- income × level of care. As described above, hospice provides two levels of care in the home setting—routine home care and continuous care. We dichotomized the level of care variable into no continuous care (enrollee did not receive continuous care at any time during hospice enrollment) vs. any continuous care (enrollee received continuous care at any time during hospice enrollment). The predictor for the multivariate model included an interaction term with each income category × any continuous care or no continuous care.

Covariates

We selected covariates based on availability in the database, and potential association with hospice enrollees transferring from home to another location prior to death or receiving a higher level of care. The final model included gender, age (<65, 65 to <75, 75 to <85, >85), race (African American, white, Hispanic, other), marital status (married, not married), disease type (cancer, other), payment source (charity, Medicaid, Medicare, other), use of a health maintenance organization (HMO), relationship of primary caregiver to enrollee, (spouse, child, other relative, non-relative, other), days on hospice (0-7, 8-30, 31-180, >180), and hospice program location by region (West, Midwest, Northeast, and South).

Statistical Analysis

To compare patients who did not transfer from home prior to death to those who did, we used chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum for continuous variables. We used logistic regression to evaluate predictors of transfer from home to another location, including all covariates as main effects and an interaction term between each category of income and any or no continuous care. We used the likelihood ratio test and the Wald test to assess the goodness-of-fit of the model. For all tests, differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample description and bivariate results

The final sample included 61,063 patients admitted to routine care in a private residence. Of these, 13,804 (22.6%) transferred from their home prior to death. Among those who transferred, 7.9% went to an assisted living facility, 13.5% to contract beds in area hospitals, 62.1% to an inpatient hospice unit, and 16.5% to a nursing home. The sample characteristics are in Table I.

Table 1. Characteristics of Hospice Enrollees.

| Variable | No transfer from home care (n=47,259) N (%) | Transferred from home care (n=13,804) N (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category | <0.001 | ||

| <65 | 10,520 (22.3) | 3118 (22.6) | |

| 65 to 74 | 10,582 (22.4) | 2895 (21.0) | |

| 75 to 84 | 14,963 (31.7) | 4336 (31.4) | |

| 85 and older | 11,194 (23.7) | 3455 (25.0) | |

| Male | 22,517 (47.7) | 6792 (49.2) | 0.001 |

| Married | 23,050 (48.8) | 5888 (42.7) | <0.001 |

| Income | <0.001 | ||

| $0-$20,000 | 730 (1.5) | 372 (2.7) | |

| >$20,000 to $30,000 | 5012 (10.6) | 2089 (15.1) | |

| >$30,000 to $40,000 | 13,254 (28.0) | 4625 (33.5) | |

| >$40,000 to $50,000 | 11,651 (24.7) | 3236 (23.4) | |

| >$50,000 | 16,612 (35.2) | 3482 (25.2) | |

| Level of Care | <0.001 | ||

| Any Continuous Care | 23,337 (49.4) | 4226 (30.6) | |

| No Continuous Care | 23,922 (50.6) | 9578 (69.4) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 33,498 (70.9) | 9350 (67.7) | |

| African American | 5927 (12.5) | 2491 (18.1) | |

| Hispanic | 6459 (13.7) | 1620 (11.7) | |

| Other | 1375 (2.9) | 343 (2.5) | |

| Hospice Region | <0.001 | ||

| West | 12,728 (26.9) | 1639 (11.9) | |

| Mid-West | 19507 (41.3) | 5454 (39.5) | |

| New England | 1914 (4.1) | 852 (6.2) | |

| South | 13,110 (27.7) | 5859 (42.4) | |

| HMO (% Yes) | 22,198 (47.0) | 6812 (49.4) | <0.001 |

| Payer Source | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 36479 (77.2) | 10863 (78.7) | |

| Medicaid | 2291 (4.9) | 1058 (7.7) | |

| Charity | 1226 (2.6) | 306 (2.2) | |

| Other | 7263 (15.4) | 1577 (11.4) | |

| Cancer | 30,370 (64.3) | 8854 (64.1) | 0.79 |

| Caregiver | <0.001 | ||

| Spouse | 21,825 (46.2) | 5735 (41.6) | |

| Child | 19,331 (40.9) | 5508 (39.9) | |

| Other relative | 5036 (10.7) | 2042 (14.8) | |

| Non-relative | 864 (1.8) | 443 (3.2) | |

| Other (p=ns) | 203 (0.4) | 76 (0.6) | |

| LOS Category | <0.001 | ||

| 0-7 | 12,515 (26.5) | 2035 (14.7) | |

| 8-30 | 17,615 (37.3) | 4910 (35.6) | |

| 31-180 | 14,451 (30.6) | 5525 (40.0) | |

| >180 | 2678 (5.7) | 1334 (9.7) |

The median household income for the sample was $42,573, similar to the US median household income for 2000 of $42,148.29 Patients who transferred from home prior to death were more likely to be in the lower income categories (<$40,000) and consistent with this had a lower average median annual household income than those who did not transfer ($42,585 vs. $46,777, P<.001). The absolute difference in probability of dying at home was 0.17 (p<0.001) between those in the highest income group (0.83) compared to the lowest income group (0.66).

Those who stayed at home were more likely to have received continuous care (49.4% vs. 30.6%, P<0.001). Among those who received any continuous care, 83.8% were receiving it at the time of death; the average duration of continuous care was 6 days (median = 4 days). Those who transferred from home had a longer mean length of stay (70.3 days vs. 48.4 days, P<0.001), were more likely to use Medicaid (7.6% vs. 4.9%, P<0.001) or be African American (18.1% vs. 12.5%, P<0.001), and were less likely to be cared for by their spouse (41.6% vs. 46.2%, P<0.001).

Multivariate Analysis

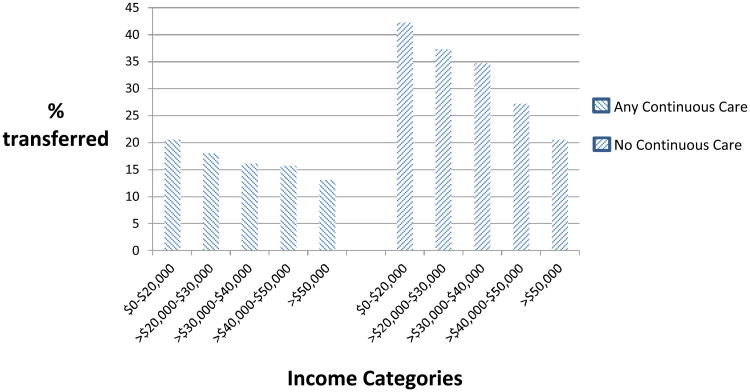

Results of the multivariate model are in Table II. The income × continuous care interaction was significant (P<0.001). Among those who did not receive continuous care, the odds of transferring from home to another location prior to death increased as median annual household income decreased. Those with a median annual household income ≤$20,000 vs. >$50,000 had almost twice the odds of transferring from home prior to death (OR 1.76, CI = 1.48-2.09). Figure I shows how income and level of care are related to transfer from home. Among those receiving continuous care, there was no significant difference in rates of transfer from home across income levels, and for all income levels, a smaller proportion of those receiving any continuous care (vs. no continuous care) transferred from home prior to death (Table II).

Table 2.

Predictors of Transfer from Home to Another Location Prior to Death Among Hospice Enrollees.

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Age Category | |

| Less than 65 | 1 |

| 65 to 74 | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.89) |

| 75 to 84 | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.92) |

| 85 and older | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.92) |

| Female Sex | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.94) |

| Married | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.92) |

| Income (with no continuous care) | |

| $0-$20,000 | 1.76 (1.48 to 2.09) |

| >$20,000 to $30,000 | 1.62 (1.49 to 1.77) |

| >$30,000 to $40,000 | 1.55 (1.45 to 1.66) |

| >$40,000 to $50,000 | 1.26 (1.17 to 1.35) |

| >$50,000 | 1 |

| Income (with any continuous care) | |

| $0-$20,000 | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.44) |

| >$20,000 to $30,000 | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.17) |

| >$30,000 to $40,000 | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.04) |

| >$40,000 to $50,000 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) |

| >$50,000 | 1 |

| Race | |

| African American | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) |

| Hispanic | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.88) |

| Other | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.28) |

| White | 1 |

| Hospice Region | |

| West | 0.26 (0.24 to 0.27) |

| Mid-West | 0.61 (0.59 to 0.64) |

| New England | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.72) |

| South | 1 |

| HMO use | |

| No | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.82) |

| Yes | 1 |

| Payer source | |

| Medicaid | 1.25 (1.12 to 1.39) |

| Charity | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.77) |

| Other source | 0.58 (0.53 to 0.64) |

| Medicare | 1 |

| Disease type | |

| Cancer | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) |

| Non-cancer | 1 |

| Caregiver | |

| Child | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) |

| Other relative | 1.19 (1.09 to 1.31) |

| Non-relative | 1.64 (1.42 to 1.90) |

| Other | 1.17 (0.87 to 1.57) |

| Spouse | 1 |

| Length of Stay | |

| 8-30 | 1.82 (1.72 to 1.93) |

| 31-180 | 2.62 (2.47 to 2.78) |

| >180 | 3.92 (3.60 to 4.28) |

| 0-7 | 1 |

The likelihood ratio test (Chi-square = 6624.1, df = 32; p<0.001) and the Wald test for this model (Wald Chi-square = 5622, df = 32; p <0.001) are significant, indicating a good fit.

Figure 1. Proportion of hospice enrollees who transferred from home to another location prior to death by intensity of care received.

Other variables associated with a higher odds of transferring from home included a payment source of Medicaid vs. Medicare (OR 1.25, CI = 1.12-1.39), a primary caregiver who was a relative other than a child (OR 1.19, CI = 1.09-1.31) or nonrelative (OR 1.64, CI = 1.42-1.90) versus spouse, and longer hospice enrollment with those enrolled more than 180 days (versus ≤ 7 days) having almost four times greater odds of transfer (OR 3.92, CI = 3.60-4.28). In contrast, Hispanics vs. Whites (OR 0.83, CI = 0.77-0.88), those not in an HMO (OR 0.78, CI = 0.75 to 0.82), women (OR 0.90, CI = 0.86-0.94), and those living in the West, Midwest, or New England vs. South were less likely to transfer from home.

Comment

In this analysis of hospice enrollees admitted to routine care in a private residence, over 1/5 of enrollees did not die at home. Among those who did not receive continuous care, those with lower annual median household incomes were more likely to transfer from home to another location prior to death. However, among those who received any continuous care, rates of transfer from home were similar across income levels. These findings suggest that those with limited socioeconomic resources may be less likely to die at home even with the support of routine home hospice. Even short periods of more intense support, such as that provided by a higher level of care (continuous care), may help overcome socioeconomic resource disparities allowing patients to die at home when consistent with their preferences.

These findings are congruent with other research demonstrating lower income patients, including those enrolled in hospice, are more likely to die in institutional settings.4,30 Although hospice provides substantial resources, the majority of direct caregiving is provided by family and friends, with hospice support provided only intermittently and for short periods. During the last year of life, more than 2/3 of patients require informal caregiving assistance.31 Many caregivers pay out of pocket for caregiving help, and many report needing help but being unable to afford it. In one estimate, care in the last six months of life totaled more than $14,000, with almost 20% of caregivers purchasing home health assistance on their own.32 Additional costs outside of those required to manage the terminal illness may add to out of pocket expenses. Costs increase over time, and our study indicates that longer lengths of stay were associated with greater odds of transfer. Because Medicaid covers the cost of room and board in a nursing home, indigent patients who qualify for Medicaid may be more likely to seek care in a nursing facility as the burdens of care in the home setting increase. However, in this study, when controlling for Medicaid, lower income in the absence of continuous care remained an independent predictor of transfer from home, suggesting that resource limitations may play a significant role in patients' ability to die at home.

In addition to physical and monetary costs of caregiving, the emotional toll is also great. In general, patients of lower socioeconomic status have a lower quality of life,33 and their caregivers have worse health and are more likely to suffer from depression.34-37 The emotional difficulties become greater when symptoms are difficult for informal caregivers to manage,38 and patients with lower incomes are more likely to have uncontrolled symptoms at the end of life.39 Less availability of home care and fewer supportive services for caregivers are associated with a decreased probability of dying at home.9

Over 90% of hospice is delivered at the routine level of care which includes medications and equipment, and intermittent visits from nurses, home health aides, chaplains and social workers. These services may not be enough to reduce the burden on informal caregivers enough to allow them to continue caring for their loved ones at home, especially those who lack financial resources to pay for additional care to subsidize that provided by hospice.40,41 In contrast to routine hospice care, continuous care is a short period of intense care in a patient's home for management of acute symptoms. In this study, continuous care was associated with an increased likelihood of dying at home regardless of income. These short periods of intense care may be most useful when death is near since 84% of those who received any continuous care were receiving it at the time of death; the median number of days of continuous care was four. Families of patients dying at home report significant issues with symptom management and care burden; changes in hospice care to provide formal caregiving or improved symptom management through increased access to continuous care could ameliorate these issues.42 The additional costs would have to be offset by decreased use of acute care, such as emergency room visits.31

In addition to the costs and demands of caregiving, because of cultural beliefs and values, some groups may not desire home death or hospice care. Prior research has demonstrated that low income and African American patients are less likely to desire home death and have less favorable attitudes towards hospice care.43,44 Therefore, while dying at home is preferred by many patients, addressing spiritual, emotional and physical symptoms and providing support at the location desired is of primary importance.

There are several limitations to this study. First, data were provided by a single, for-profit hospice provider servicing 8 states; our findings may not be typical of other providers. For example, VITAS hospice had a lower rate of deaths in the home setting (34% vs. 40%), shorter mean length of stay (41 vs. 69 days), and a higher percentage of continuous care days (5.9% vs. 1.2%) than the national average.18 Consistent with national trends, Medicare paid for the majority of care and rates of charity care were similar to or greater than the national average (2.5% vs 2.2%).19 Rates of home deaths may vary by hospice provider and, as in this study, prior research has shown variation in home deaths by state and region.45 Additionally, while guidelines for use of continuous care are included in the Medicare Hospice Benefit, there is likely some variation across hospices in when and how this level of care is provided based on available resources and additional guidelines defined by individual providers.

Although data included patients admitted from 1999 to 2003, the structure of the Medicare hospice benefit, per diem payment structure, and criteria for eligibility for the different levels of care remain largely unchanged.46 Patients' share of costs remains minimal, and enrollment in hospice has increased substantially.47 While the current population of hospice patients includes a greater percentage of non-cancer diagnoses than in our study, this sample included a significant proportion of non-cancer diagnoses and the logistic regression showed a minimal effect of this variable. Almost half of all hospice patients currently receive care in a private residence, the defining population for this analysis.18 More than half of all hospices are for-profit, and analyses of proprietary data from a national hospice formed part of the basis for proposed changes to the current hospice payment structure.47 Large hospices, whose increased resources are often required to provide continuous care, have become more prominent, making this sample representative of the current expansion of hospice services.

While it is likely that many patients admitted to hospice in a private residence wanted to die at home, we do not have information about the preferences of individual hospice enrollees or reasons for transfer from home. Large prospective studies are needed to capture the many factors which determine place of death. Lastly, individual incomes were not available in this database, and therefore, we matched patient zip codes to census tract information to generate median household incomes. This method has been used in other research, but is limited, particularly in areas where there may be large individual variability in income.28,48-50

Indigent patients suffer from decreased access to healthcare, worse outcomes, and overall worse health-related quality of life.33 In this study we found an association between low income and decreased likelihood of remaining at home until death among home hospice patients. Our findings suggest that hospices may need to provide additional resources to help indigent patients die at home beyond those currently available via routine hospice. Such resources would likely include increased access to short periods of more intense care during times of crisis to manage uncontrolled physical and emotional symptoms and other sources of caregiver burden such as those currently available via continuous care. Future research is needed to develop models of care which ensure access to high quality end of life care for all patients regardless of income.13

Acknowledgments

Joshua Barclay and Kimberly Johnson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding Sources: This analysis was supported by K08AG028975 – Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research and Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Footnotes

Related Presentations and Published Abstracts: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Annual Assembly 2009. Austin, TX. Poster Presented March 25-28, 2009 (poster hung for these dates, no formal presentation). Abstract published: Barclay, JS, and Johnson, KS. Association between income and rate of transfer from home hospice. J Pain and Symptom Manage. 2009. 37(3): 535

Financial Disclosure: This analysis uses data from the VITAS Healthcare Corporation. It was not funded by VITAS and does not reflect the views of the VITAS Healthcare Corporation. Vitas had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, preparation or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Abarshi E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Donker G, Echteld M, Van den Block L, Deliens L. General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(4):568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(3):245–251. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muramatsu N, Hoyem RL, Yin H, Campbell RT. Place of death among older Americans: does state spending on home- and community-based services promote home death? Med Care. 2008;46(8):829–838. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181791a79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor EJ, Ensor B, Stanley J. Place of death related to demographic factors for hospice patients in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand. Palliat Med. 2012;26(4):342–349. doi: 10.1177/0269216311412229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell M, Grande G, Wilson C, Caress AL, Roberts D. Exploring differences in referrals to a hospice at home service in two socio-economically distinct areas of Manchester, UK. Palliat Med. 2010;24(4):403–409. doi: 10.1177/0269216309354032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed May 22, 2012];Health, United States, 2010: With special feature on death and dying. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf. [PubMed]

- 7.Grande GE, Addington-Hall JM, Todd CJ. Place of death and access to home care services: are certain patient groups at a disadvantage? Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(5):565–579. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of place of death for terminal cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(2):165–180. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura S, Kuzuya M, Funaki Y, Matsui W, Ishiguro N. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill cancer patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10(2):154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515–521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koffman J, Burke G, Dias A, et al. Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med. 2007;21(2):145–153. doi: 10.1177/0269216306074639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):754–762. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silveira MJ, Connor SR, Goold SD, McMahon LF, Feudtner C. Community supply of hospice: does wealth play a role? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairfield KM, Murray KM, Wierman HR, et al. Disparities in hospice care among older women dying with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(1):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. [Accessed October 8, 2012];NHPCO Facts and Figures 2003. http://www.lmhpco.org/professionals/publications/Hospice_Facts_110104.pdf.

- 16.Fukui S, Kawagoe H, Masako S, Noriko N, Hiroko N, Toshie M. Determinants of the place of death among terminally ill cancer patients under home hospice care in Japan. Palliat Med. 2003;17(5):445–453. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm782oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang ST, McCorkle R, Bradley EH. Determinants of death in an inpatient hospice for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2(4):361–370. doi: 10.1017/s1478951504040489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed 11/22/11, 2011];NHPCO Facts and figures: Hospice care in America. 2010 http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/Hospice_Facts_Figures_Oct-2010.pdf.

- 19.Connor SR. U.S. hospice benefits. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(1):105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallo WT, Baker MJ, Bradley EH. Factors associated with home versus institutional death among cancer patients in Connecticut. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(6):771–777. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatala M, Sloane RJ, Tanis D, Galanos AN, Tulsky JA. Ethnic differences in the place of death of elderly hospice enrollees. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2209–2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decker SL, Higginson IJ. A tale of two cities: factors affecting place of cancer death in London and New York. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(3):285–290. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(12):2431–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and medicare expenditures for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(28):4371–4375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cintron A, Hamel MB, Davis RB, Burns RB, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Hospitalization of hospice patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(5):757–768. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in hospice revocation to pursue aggressive care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(2):218–224. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence from national samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(5):475–486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Census U. [Accessed October 2, 2012];Money income in the United States: 2000 - Median household income by state. 2012 http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/incpovhlth/2000/statemhi.html.

- 30.Houttekier D, Cohen J, Bilsen J, Deboosere P, Verduyckt P, Deliens L. Determinants of the place of death in the Brussels metropolitan region. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(6):996–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Houtven CH, Taylor DH, Jr, Steinhauser K, Tulsky JA. Is a home-care network necessary to access the Medicare hospice benefit? J Palliat Med. 2009;12(8):687–694. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, Atienza AA, van Ryn M. Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(8):883–893. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robert SA, Cherepanov D, Palta M, Dunham NC, Feeny D, Fryback DG. Socioeconomic status and age variations in health-related quality of life: results from the national health measurement study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(3):378–389. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang CY, Sousa VD, Perng SJ, et al. Stressors, social support, depressive symptoms and general health status of Taiwanese caregivers of persons with stroke or Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(4):502–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang B, Mitchell SL, Bambauer KZ, Jones R, Prigerson HG. Depressive symptom trajectories and associated risks among bereaved Alzheimer disease caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(2):145–155. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318157caec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y, Spillers RL. Quality of life of family caregivers at 2 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2010;19(4):431–440. doi: 10.1002/pon.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans WG, Cutson TM, Steinhauser KE, Tulsky JA. Is there no place like home? Caregivers recall reasons for and experience upon transfer from home hospice to inpatient facilities. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(1):100–110. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silveira MJ, Kabeto MU, Langa KM. Net worth predicts symptom burden at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(4):827–837. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutner J, Kilbourn KM, Costenaro A, et al. Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1101–1104. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii Y, Miyashita M, Sato K, Ozawa T. Family's Difficulties in Caring for a Cancer Patient at the End of Life at Home in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1953–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barclay J, Coffman CJ, Johnson KS. Annual income and hospice knowledge and attitudes in a sample of community dwelling older adults. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):305. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weitzen S, Teno JM, Fennell M, Mor V. Factors associated with site of death: a national study of where people die. Med Care. 2003;41(2):323–335. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044913.37084.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicosia N, Reardon E, Lorenz K, Lynn J, Buntin MB. The Medicare hospice payment system: a consideration of potential refinements. Health Care Financ Rev. 2009;30(4):47–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iglehart JK. A new era of for-profit hospice care--the Medicare benefit. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2701–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee PR, Moss N, Krieger N. Measuring social inequalities in health. Report on the Conference of the National Institutes of Health. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(3):302–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas AJ, Eberly LE, Davey Smith G, Neaton JD. ZIP-code-based versus tract-based income measures as long-term risk-adjusted mortality predictors. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(6):586–590. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soobader M, LeClere FB, Hadden W, Maury B. Using aggregate geographic data to proxy individual socioeconomic status: does size matter? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):632–636. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]