Summary

The ubiquitin-modification status of proteins in cells is highly dynamic and maintained by specific ligation machineries (E3 ligases) that tag proteins with ubiquitin or by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove the ubiquitin tag. The development of tools that offset this balance is critical in characterizing signaling pathways that utilize such ubiquitination switches. Herein, we generated a DUB-resistant ubiquitin mutant that is recalcitrant to cleavage by various families of DUBs both in vitro and in mammalian cells. As a proof of principle experiment, ectopic expression of the uncleavable ubiquitin stabilized mono-ubiquitinated PCNA in the absence of DNA damage, and also revealed a defect in the clearance of the DNA damage response at unprotected telomeres. Importantly, a proteomic survey using the uncleavable ubiquitin identified previously unknown ubiquitinated substrates, validating the DUB-resistant ubiquitin expression system as a valuable tool to interrogate cell signaling pathways.

Keywords: deubiquitination, DUBs, PCNA, ubiquitin, DUB-resistant, TRF2

Introduction

The ubiquitination status of a target protein is achieved via a delicate balance between two opposing forces: ubiquitin E3 ligases and DUBs. It has been postulated that the majority of proteins in a cell are regulated and modified by ubiquitin at some point (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998); however, it has proven difficult to demonstrate the ubiquitination status of these proteins, as many of the modifications only exist transiently in vivo, owing largely to the multitude of DUBs present in cells. There are nearly one hundred DUBs encoded in the human genome, which comprise approximately 1/5 of all proteases (Rawlings et al., 2010). DUBs are divided into five subfamilies based on catalytic mechanism and the fold of the active site domain (Reyes-Turcu et al., 2009). The largest family are the Ubiquitin Specific Proteases (USPs), followed by the Ovarian Tumor DUBs (OTUs), the Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), the Josephin DUBs, and lastly, the JAMM/MPN+ family member DUBs. Except for the JAMM/MPN+ family of DUBs, which are zinc-dependent metalloproteases, all other characterized DUBs are cysteine proteases. As the ubiquitin-modified status of a protein can fundamentally alter its properties and change its biological role, it is critical to capture the ubiquitinated state of a protein in order to investigate its biological function both in vitro and in vivo.

The ubiquitin system has recently been exploited with the design of unique ubiquitin mutants that inhibit specific DUBs (Ernst et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). While the specificity of such mutants is remarkable, generating a novel mutant for each DUB has to begin de novo and is quite laborous, especially when the physiological substrates of many DUBs remain unknown. In this study, we designed and generated a DUB-resistant ubiquitin to capture and identify transiently ubiquitinated DUB substrates. Building on previous work in the SUMO conjugation and deconjugation pathway (Bekes et al., 2011), we have generated a ubiquitin mutant (UbL73P) that is pleiotropically resistant to cleavage by multiple DUB families. This uncleavable ubiquitin mutant is conjugated to protein substrates in mammalian cells and leads to ubiquitin-conjugate stabilization. Ectopic expression of the DUB-resistant ubiquitin mutant stabilized mono-ubiquitinated PCNA, leading to the aberrant recruitment of translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases in the absence of DNA damage, mimicking the effect of USP1 loss. Further studies with DUB-resistant ubiquitin revealed a ubiquitin switch in the clearance of the DNA damage response (DDR) at shelterin-deficient chromosomal ends, and captured novel ubiquitin-stabilized substrates by mass spectrometry. Our work provides a framework to study deubiquitination-dependent events both in vitro and in mammalian cells through the generation and use of the DUB-resistant ubiquitin tool.

Results

Ubiquitin-L73P is a DUB-resistant ubiquitin mutant

To establish a ubiquitin mutant that would be resistant to cleavage by DUBs, we mutated Leu73 of ubiquitin to Pro. Leu73 is the P4 position of the DUB cleavage site in the C-terminus of ubiquitin (Figure 1A); the analogous mutation in SUMO2 (Supplementary Figure 1A) results in a conjugatable but deconjugation-resistant SUMO (Bekes et al., 2011). To test the “uncleavability” of UbL73P in the context of a linear peptide-bond, we expressed recombinant linear di-ubiquitin (M1-linked) containing the L73P mutation in both ubiquitin moieties with an N-terminal Smt3-tag (Figure 1B) and tested it as a substrate for USP2CD (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1B). While the wild-type (WT) fusion protein is cleaved by USP2CD, the mutant (L73P) is not. To ensure that the Smt3-tag did not interfere with cleavage of the L73P di-Ub, the tag was removed via cleavage with Ulp1 and the di-Ub was purified to homogenity and subjected again to USP2CD cleavage (Figure 1D). These results show that in the context of a linear peptide bond, L73P is refractory to cleavage.

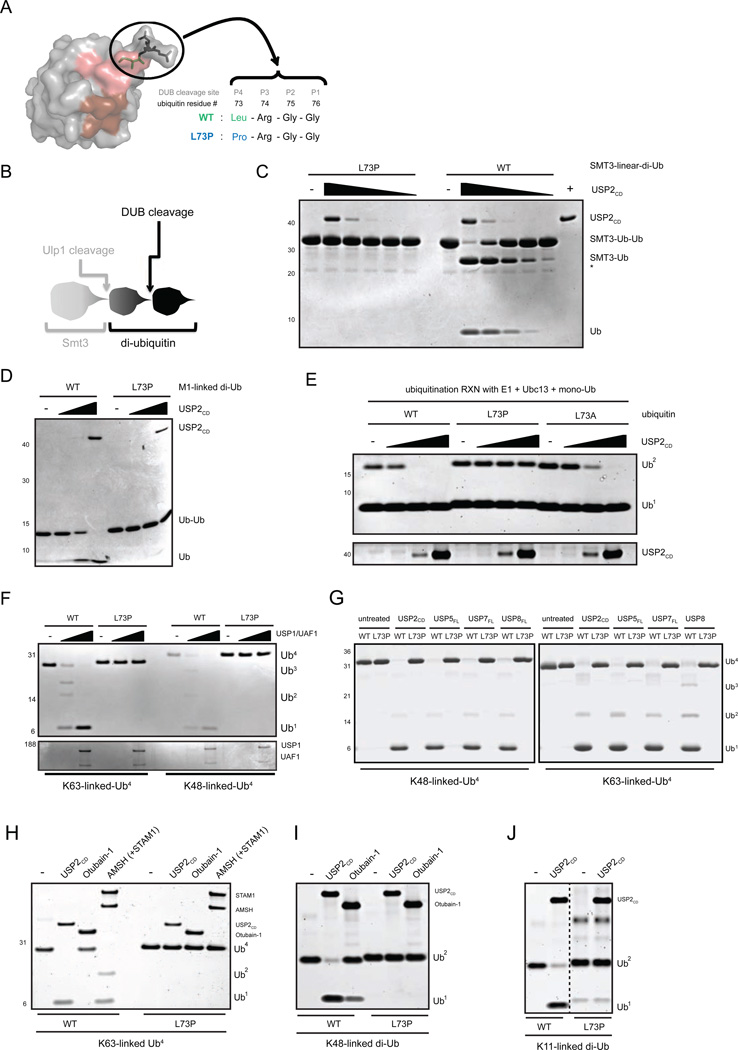

Figure 1. UbL73P is a pan-DUB DUB-resistant ubiquitin mutant in vitro.

(A) Surface representation of ubiquitin (PDB: 1UBQ) detailing its C-terminus. The DUB cleavage site (P4-P1, aa 72–76 of ubiquitin) is shown in sticks (in black), with Leu73 shown in green. The Ile44 hydrophobic patch is colored brown on the surface, while the Ile36 hydrophobic patch is colored pink. The image was generated using PyMol. (B) Schematic representation of Smt3-tagged linear di-ubiquitin. Ubiquitin L73P is not cleaved by DUBs neither as a peptide or an iso-peptide bond. Wild-type and L73P Smt3-linear-di-Ub, before (C) and after (D) Ulp1-cleavage and final purification, was cleaved with a serial dilution of USP2CD. (E) Untagged mono-ubiquitins were used to make K63-linked di-ubiquitins using Ubc13/Uev1a, then subjected to cleavage by USP2CD. (F) Recombinant USP1/UAF1 complex was used to cleave wild-type and L73P (NH) tetra-ubiquitin chains in vitro. (G) Linkage-specific tetra-ubiquitin chains (K48-linked, left panel, or K63-linked, right panel) made using either wild-type or L73P ubiquitin (non-hydrolyzable (NH) chains) were cleaved with an assortment of USP-family DUBs. (H) DUBs representing the USP-family (USP2CD), the OTU-domain family (Otubain-1) and the JAMM-metallo-DUBs (AMSH) were used cleave wild-type and NH K63-linked tetra-ubiquitin chains. Otubain-1 serves as a negative control for K63. (I) Otubain-1 and USP2CD were used to cleave K48-linked di-ubiquitin. (J) USP2CD was used to cleave K11-linked di-ubiquitin. Dotted lines indicate cropping within the same gel. Assays were carried out at 37°C for 1 hour and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and coomassie-staining. See also Figure S1.

To test whether UbL73P in the context of an isopeptide-bond is also resistant to cleavage, we generated K63-linked ubiquitin chains using Ubc13 (UBE2N-Uev1a) in an in vitro ubiquitination reaction (Supplementary Figure 1C, lanes 1–2 and 5–6). Whereas wild-type di-ubiquitin prepared using Ubc13 is cleaved by USP2CD (Figure 1E, lanes 1–4), di-UbL73P is completely resistant to cleavage (Figure 1E, lanes 5–8). Additionally, higher molecular weight, unanchored poly-ubiquitin chains, also prepared using Ubc13, are likewise resistant to cleavage in the context of UbL73P (Supplementary Figure 1C, lanes 3–4 and 7–8). Interestingly, the more conservative L73A mutation on ubiquitin is only partially resistant to cleavage by USP2CD (Figure 1E, lanes 9–12). This suggests that it is the combination of the altered topology of the proline residue; the loss of the hydrophobic interaction provided by the leucine side-chain; and the loss of its hydrogen-bonding ability to Asp295 of USP2 (Renatus et al., 2006) that renders UbL73P “uncleavable” (Supplementary Figure 1D). Consistent with the latter being most significant, mutation of USP7 Asp295 to Ala results in an inactive enzyme (Hu et al., 2002). We show that purified linkage-specific ubiquitin chains produced in vitro are also resistant to cleavage by multiple USP-family members (Figure 1F and 1G), by the K63-specific JAMM-family member, AMSH (Figure 1H) and by the K48-specific OTU-domain family member, Otubain-1 (Figure 1I). Finally, we show that K11-linkages are also resistant to cleavage (Figure 1J). Collectively, these in vitro studies establish UbL73P as a pan-DUB resistant ubiquitin mutant, encompassing both cysteine protease and metallo-enzyme DUBs.

Cleavage resistant UbL73P is conjugated to substrates both in vitro and in vivo

We have previously shown that UbL73P supports unanchored ubiquitin chain formation by Ubc13 as the E2 enzyme (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure 1C). However, owing to the unique topology of UbL73P, we postulated that not all ubiquitin conjugation pathways will utilize it equally. Thus, we asked whether the two human E1 enzymes, Ube1 and Uba6, which have been shown to dictate downstream ubiquitination events in vivo (Jin et al., 2007), showed preference between wild-type and UbL73P. In an in vitro E1 charging reaction, Ube1 and Uba6 differ only slightly in UbL73P charging (Figure 2A), however, Uba6 cannot use UbL73P in charging UbcH7 in an E2-charging reaction (Figure 2B). Importantly, when UbL73P is utilized by Ube1 to charge an E2 enzyme, it depends on the active site cysteine of the E2, indicating that the charging is enzyme-catalyzed (Supplementary Figure 2A). Together, these results suggest that UbL73P usage in vivo is dictated at the E1 level; differences in E1 thioester formation between Ube1 and Uba6 could be due to the different residues that contact Leu73 in Ube1 and Uba6 (Supplementary Figure 2B–C) during E1 charging (Olsen and Lima, 2013). On the other hand, there is no crystal structure available for a charged E2 enzyme still bound to an E1, therefore the differential E2 charging ability of Uba6 in the context of UbL73P is difficult to explain mechanistically at this stage.

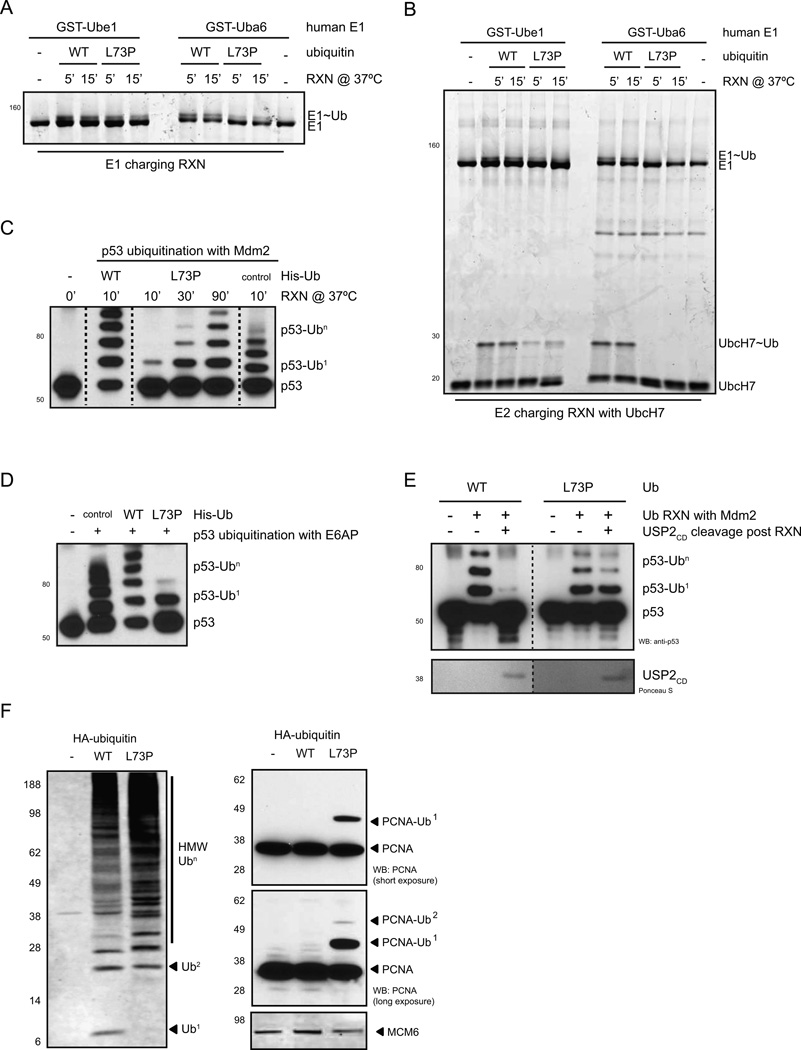

Figure 2. UbL73P is conjugated to substrates in vitro and in vivo.

(A) E1 charging assay with GST-tagged human Ube1 and Uba6 using wild-type and L73P ubiquitin. (B) E2 charging assay using human GST-tagged Ube1 and Uba6 as the E1 and human UbcH7 as the E2, using wild-type and L73P ubiquitin (F). E1 and E2 charging reactions were carried out at 37°C in the absence of DTT and analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and SYPRO-staining. (C) and (D) p53-ubiquitination reactions with wild-type and L73P ubiquitin using either a RING-finger E3 ligase, Mdm2 (C) or a HECT-domain E3 ligase, E6AP (D). Ubiquitination reactions with the E3 ligases were analyzed by denaturing SDS-PAGE and western blotting with an anti-p53 antibody. Dotted lines indicate cropped images from the same gel. (E) Mdm2-generated ubiquitin chains on p53 using WT or L73P ubiquitin were cleaved with USP2CD following ubiquitination reactions. (F) Expression of HA-tagged wild-type and L73P ubiquitin in U2OS cells results in stabilization of Ub-conjugates by L73P, such as PCNA-Ub. See also Figure S2.

Since Leu73 is part of the Ile36 hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin that is important in ubiquitin chain assembly (Komander and Rape, 2012), we asked whether the L73P mutation affects conjugation to substrates using E3 ligases. The recently solved crystal structures of RING-E2:E3 complexes highlight an intermediate role of Leu73 in E2–E3 interactions (Dou et al., 2012; Plechanovova et al., 2012). Consistent with the structural analysis, UbL73P is conjugated to the model substrate p53 by both RING- and HECT-domain E3 ligases with reduced efficiency (Mdm2, Figure 2C and E6AP, Figure 2D, respectively). Importantly however, UbL73P-conjugated p53-Ubn remains uncleavable by USP2CD (Figure 2E).

We next sought to determine whether UbL73P, when expressed in mammalian cells, is incorporated into ubiquitin conjugates. We generated N-terminal HA-tagged wild-type and L73P ubiquitin constructs ending in Gly76 to allow for immediate conjugation. When expressed in U2OS cells, UbL73P forms Ub-conjugates similar to wild-type Ub, with a modest increase in higher-molecular weight (HMW) Ub-conjugates (Figure 2F, left panel), likely forming heterogenous chains with endogenous ubiquitin. Under these conditions, levels of ectopically expressed ubiquitin do not reach endogenous levels, as judged by total Ub (Supplementary Figure 3A–B).

Intriguingly, expression of UbL73P resulted in a marked increase in the mono-ubiquitination of PCNA (Figure 2F, right panel), a substrate previously shown to be mono-ubiquitinated under DNA damage conditions (Hoege et al., 2002). Non-specific ubiquitination was not observed for other proteins, such as MCM6 (Figure 2F, bottom). Importantly, we show that PCNA modification with cleavage-resistant modifiers is specific to ubiquitin, as cleavage-resistant SUMO2 does not stabilize PCNA-conjugates under normal conditions (Supplementarty Figure 3C). The mono-ubiquitination of PCNA is usually reversed by USP1 (Huang et al., 2006), however, USP1 does not cleave UbL73P chains (Figure 1F). These results strongly suggest that the UbL73P-stabilized PCNA mono-ubiquitination is a result of the failure of USP1 to cleave UbL73P from PCNA in cells.

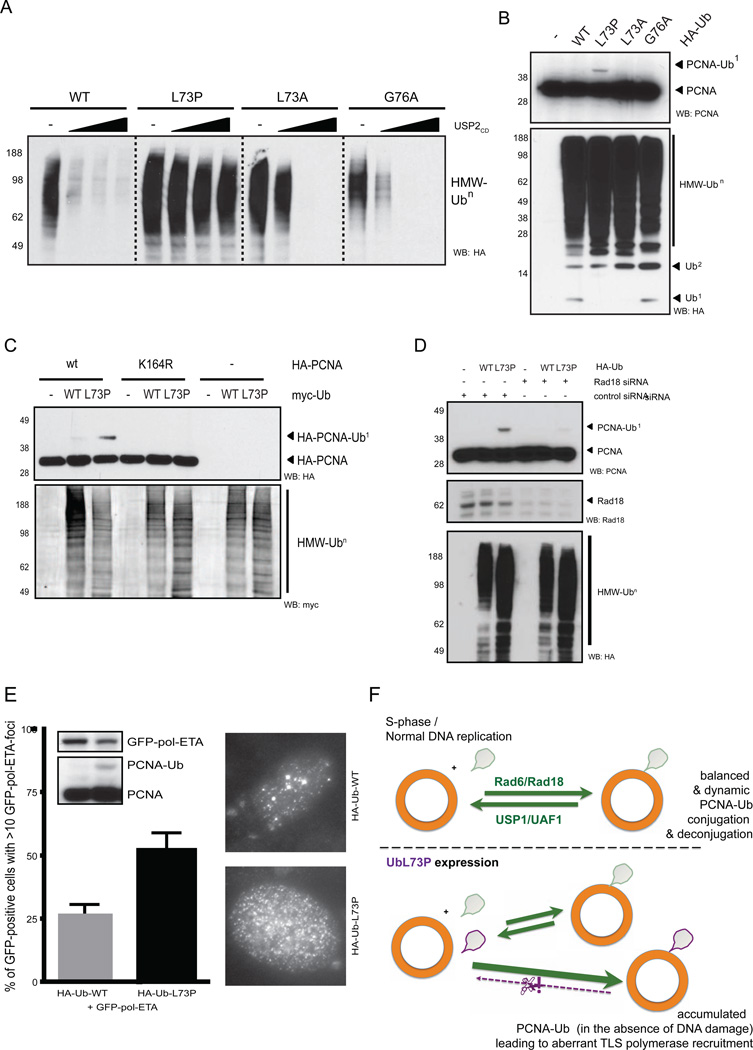

Figure 3. Dynamic PCNA mono-ubiquitination revealed by UbL73P.

(A) HA-Ub constructs were expressed in HEK293 cells, lysed under non-denaturing conditions and the lysates were treated with a serial dilution of USP2CD. (B) HA-Ub constructs were expressed in U2OS cells and lysed under denaturing conditions. (C) PCNA with a K164R mutation does not support mono-ubiquitination by UbL73P. HA-PCNA and myc-ubiquitin constructs were co-expressed in U2OS cells and lysed under denaturing conditions. (D) UbL73P is conjugated in a Rad18-dependent manner in vivo. U2OS cells were treated with siRNAs for 24 hours, then transfected with HA-ubiquitin for another 48 hours when cell lysates were prepared under denaturing conditions. (E) UbL73P-stabilized PCNA-Ub recruits polymerase eta in the absence of DNA damage. HA-tagged Ubs were co-expressed with GFP-tagged Pol eta in U2OS cells, fixed in methanol, mounted with DAPI and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using anti-GFP antibodies for nuclear GFP-ETA foci. The inlets show representative images and western blots for the cell lysates analyzed. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean, n=3. (F) Dynamic PCNA mono-ubiquitination revealed by UbL73P. Under normal circumstance in S-phase (top panel) the E3 ligase Rad18 mono-ubiquitinates PCNA, which is counter-balanced by USP1, the DUB for PCNA. When a conjugatable, but not deconjugatable ubiquitin (L73P, bottom panel) is expressed in cells, the USP1-arm of the dynamic PCNA monoubiquitation cycle is poisoned, leading to the stabilization of PCNA-Ub. See also Figure S3.

UbL73P expression inhibits the deubiquitination of PCNA in the absence of DNA damage

We next focused on how stabilized UbL73P-conjugates lead to higher levels of PCNA mono-ubiquitination (Figure 2F). UbL73P-conjugates produced from cells remain refractory to an in vitro DUB (USP2) cleavage assay (Figure 3A, lanes 1–8). Interestingly, while expression of both UbL73A and UbG76A give rise to similar patterns of HMW ubiquitin conjugates in cells, they remain relatively sensitive to cleavage by USP2CD in vitro (Figure 3A, lanes 9–16). An earlier study showed that UbG76A can accumulate as K48-linked unanchored ubiquitin oligomers in cells (Hodgins et al., 1992). Collectively, this suggests that UbG76A is not universally refractory to cleavage by DUBs, but it is resistant only to USP5 (IsoT)-mediated deubiquitination (Dayal et al., 2009), which requires an intact C-terminal GlyGly motif for unanchored chain deconjugation (Wilkinson et al., 1995).

In agreement with the DUB cleavage sensitivity of different ubiquitin mutants in vitro (Figure 1E and Figure 3A), expression of neither UbL73A nor UbG76A stabilize PCNA mono-ubiquitination in cells (Figure 3B). Importantly, we show that PCNA monoubiquitination by UbL73P is restricted to the canonical ubiquitination lysine of PCNA, as co-expression of a K164R PCNA mutant does not support mono-ubiquitination with UbL73P (Figure 3C). We also show that UbL73P-stabilized PCNA mono-ubiquitination is dependent on the endogenous E3 ligase for PCNA, Rad18 (Kannouche et al., 2004), since siRNA knock-down of Rad18 reduces PCNA mono-ubiquitination levels (Figure 3D). These results strongly suggest that UbL73P conjugation is specific to a physiological substrate, its lysine residue and occurs via its endogenous E3 ligase. Finally, we show that UbL73P-stabilized PCNA mono-ubiquitination aberrantly recruits TLS polymerase ETA to the replication fork, represented by nuclear foci (Figure 3E). This is in accordance with earlier work showing that knockdown of USP1, which leads to the accumulation of mono-ubiquitinated PCNA even in the absence of DNA damage, is sufficient to recruit TLS polymerases to the replication fork and forms nuclear foci (Jones et al., 2012). These results demonstrate that UbL73P is utilized similarly as wildtype ubiquitin and is conjugated onto protein substrates in UbL73P-expressing cells. This “proof-of-principle” highlights the use of UbL73P as a tool to reveal ubiquitin switches (as demonstrated by the balance between ubiquitin conjugation and deconjugation cycles), such as for PCNA in unperturbed cells (Figure 3F).

UbL73P expression attenuates the clearance of 53BP1 foci after telomeric DDR in shelterin-deficient MEFs

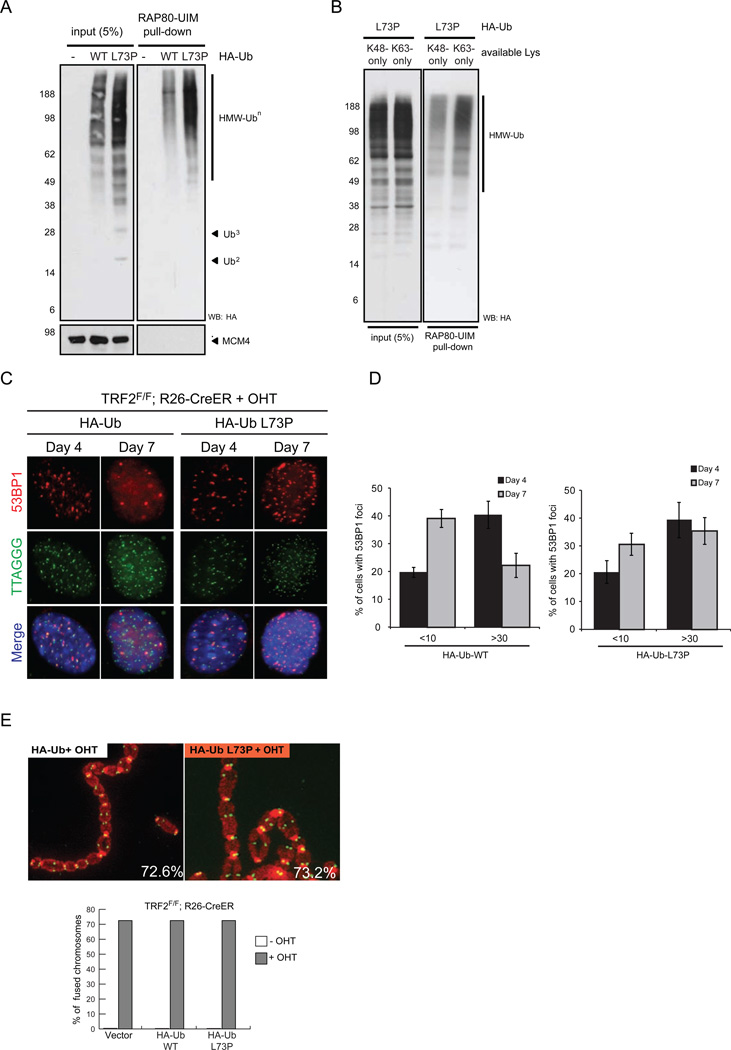

We next sought to determine whether UbL73P can be used to interrogate DNA repair pathways that are regulated by ubiquitin switches. Distinct E3 ligases and DUBs are critical regulators of the double-strand break repair and response in mammalinan cells (Jackson and Durocher, 2013). Signaling and repair emanating from DNA damage recognition is carried out, in part, through mono- and poly-ubiquitin interactions with different ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) on specific DNA damage response (DDR) proteins. To determine if UbL73P can be utilized and recognized by DDR proteins, we first addressed whether UbL73P-conjugates are recognized by UBDs other than those of the TLS polymerases. Indeed, UBD-pull-down experiments using the UIMs (ubiquitin interacting motif) of RAP80 (Figure 4A) and S5a (Supplementary Figure 4A) indicate that polyubiquitin conjugates from cell extracts that have incorporated UbL73P are efficiently captured by different UBDs. To address whether K63 linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains can be recognized and captured by the RAP80 UBD in the context of the UbL73P-stabilized chains, UbL73P containing only a single lysine site at K63 was expressed in cells and was shown to form polyubiquitin chains that could be selectively enriched by the RAP80 UBD in a pull-down experiment (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Ubiquitin-conjugate stabilization reveals a telomeric DNA damage response phenotype.

RAP80-mediated pull-down of UbL73P-conjugates. (A) and (B) HA-ubiquitin constructs were expressed in HEK293 cells, lysed under non-denaturing conditions and Ub-conjugates were pulled-down with RAP80-conjugated beads, then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting for the indicated antibodies. (C) TRF2F/F; Rosa26 CRE-ER MEFs infected with the indicated constructs were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (+OHT) and stained for 53BP1 (red), telomere DNA (green), and DAPI (blue). (D) Quantification of cells with less than 10 53BP1 foci (<10) or more than 30 53BP1 foci (>30) per nucleus at the indicated time points following OHT treatment. (E) Metaphase spreads were harvested from TRF2F/F; Rosa26 CRE-ER MEFs seven days following OHT treatment. Cells were infected with either HA-Ub or HA-UbL73P and stained for telomere DNA (green) and DAPI (red). Percentages of chromosomes with fusions are indicated. Bar graph in the lower panel indicates the percentage of chromosome fusions in MEFs infected with the indicated constructs and either treated with tamoxifen (+OHT) or untreated (−OHT). See also Figure S4.

A critical DDR regulator is the RAP80 DUB complex, containing the K63 linkage-specific metalloprotease BRCC3 (Kim et al., 2007; Sobhian et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). Based on the observation that RAP80 UIMs bind UbL73P-stabilized K63-Ub-conjugates and the recent report supporting the requirement of BRCC3 to prevent the accumulation of 53BP1 foci at telomeres in the absence of the shelterin component, TRF2 (Okamoto et al., 2013), we sought to determine whether expression of UbL73P contributes to the dynamics of 53BP1 foci accumulation. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking TRF2, spontaneous activation of DDR occurs, leading to γH2AX (Ser139 phosphorylation) and 53BP1 foci accumulation at the chromosome ends. These DNA damage foci are cleared following the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-mediated “repair” of dysfunctional telomeres that results in end-to-end chromosome fusions (Celli and de Lange, 2005). To determine whether expression of UbL73P prevents dissipation of the DNA damage signal in this experimental setting, we compared lentiviral transduction of UbWT or UbL73P in 4-hydroytamoxifen-treated Trf2Floxed/Floxed MEFs carrying an inducible Cre recombinase (Rosa26-CreERT2) to activate DDR (Okamoto et al., 2013). Following Cre activation, we monitored 53BP1 localization at telomeres immediatelly after TRF2 depletion (day 3) and at a later time point when the vast majority of telomeres have been processed by the NHEJ-mediated repair (day 7). Intriguingly, while the initial accumulation of 53BP1 foci is not affected by UbL73P, the clearance of 53BP1 foci is significantly attenuated at day 7 (Figure 4C and 4D, right panels), suggesting that deubiquitination (likely through BRCC3) is required for 53BP1 clearance. Importantly, UbL73P expression does not globally activate DDR on its own (as observed by the absence of spontaneous γH2AX levels) nor does it affect the rate of NHEJ at telomeres, as judged by occurrence of telomere fusions (Figure 4E). On the contrary, expression of UbL73P does not affect the clearence of DNA damage foci at DSBs occurring randomly in the genome, as shown by the dissipation of 53BP1 foci in cells treated with ionizing radiation (IR) or bleomycin (Supplementary Figure 4B–D). These results suggest that while clearence of DDR factors at TRF2-depleted telomeres depends strictly on a UbL73P-stabilized protein substrate(s), additional pathways may act at DSBs that occurred randomly in the genome. Similarly, activation of the DDR at TRF2-depleted telomeres is strictly dependent on the ATM DDR kinase, while irradiation induced foci (IRIFs) are largely unaffected in ATM-deficient cells (Denchi and de Lange, 2007).

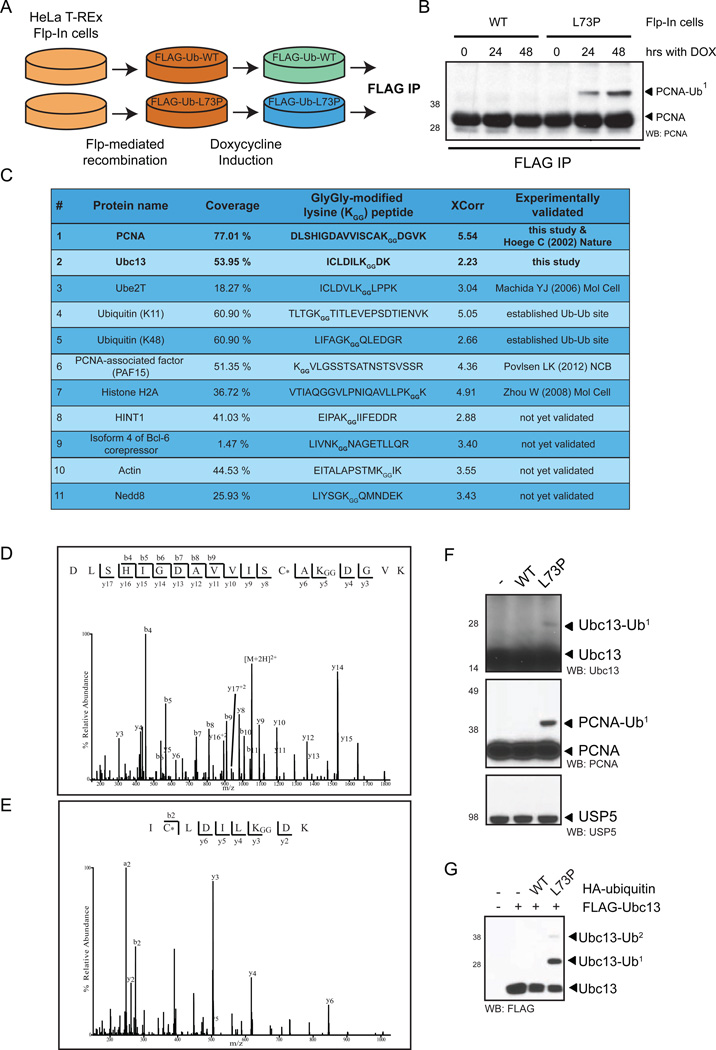

Identification of ubiquitin-stabilized substrates in HeLa cells using an UbL73P expression system

We sought to establish the utility of UbL73P in identifying novel ubiquitin-stabilized substrates by creating a stable cell line expressing UbL73P, purifying Ub-conjugates and identifying the substrates and ubiquitination sites by mass-spectrometry. We generated a doxycyclin-inducible HeLa cell line stably expressing low levels of FLAG-Ub-WT (Flp-in-WT) and FLAG-Ub-L73P (Flp-in-L73P) (Figure 5A). Purifying FLAG-conjugates from Flp-in cells confirmed PCNA-Ub stabilization using UbL73P (Figure 5B), while the low levels of FLAG-Ub-L73P expressed did not affect the NF κ B signaling pathway, as ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of I κ B α following TNF-α treatment was comparable in both Flp-in-WT and Flp-in-L73P cells (Supplemetary Figure 4E). Next, we scaled up and purified FLAG-Ub conjugates from Flp-in-L73P cells and subjected them to mass-spectrometry-based protein identification. We identified potential ubiquitinated substrates, including previously known and unknown ones (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, we were also able to identify ubiquitination sites for a handful of proteins (Figure 5C), including Lys164 of PCNA (Figure 5D), validating our approach. Interestingly, we identified Ubc13 as a novel ubiquitinated substrate at Lys92 (Figure 5E). The ubiquitination stabilization of Ubc13 by UbL73P, and not by WT ubiquitin, was confimed in U2OS cells for endogenous Ubc13 (Figure 5F) as well as by co-expression of FLAG-Ubc13 and HA-ubiquitins (Figure 5G). These results unequivocally demonstrate the utility of UbL73P in stabilizing and identifying ephemeral ubiquitin conjugates that would otherwise constantly undergo deubiquitination by DUBs.

Figure 5. UbL73P reveals stabilized ubiquitination of Ubc13 and other targets.

(A) Schematics for the generation of HeLa Flp-in cells stably expressing ubiquitin constructs. (B) Anti-FLAG immune-precipitation of Flp-in cells treated for the indicated times with doxycycline to induce transgene expression, probed with anti-PCNA antibody. (C) Selected list of proteins conjugated by UbL73P and the peptides containing the Ub-modified Lys residues. (D) MS/MS spectrum of the doubly charged ion of the peptide (DLSHIGDAVVISCAKGGDGVK carboxymethylated on the Cys (*) residue and carrying a GlyGly modification on the first lysine residue) for Lys164 of PCNA, (E) MS/MS spectrum of the triply charged ion of the peptide (ICLDILKGGDK carboxymethylated on the Cys (*) residue and carrying a GlyGly modification on the first lysine residue) for Lys92 of Ubc13. Observed peptide bond cleavages are indicated in the sequences. The corresponding theoretical N-terminal (b-type ion) and C-terminal (y-type ions) ion series for the observed fragment ions are shown above and below the sequence, respectively. Neutral loss of water from y- and b- type ions are not indicated in the spectra. (F) HA-Ub constructs were expressed in U2OS cells, lysed under non-denaturing conditions and probed with the indicated antibodies. (G) FLAG-Ubc13 and HA-Ub constructs were co-expressed in U2OS cells, lysed under denaturing conditions and probed with anti-FLAG antibody. See also Figure S4 and Table S1.

Discussion

In summary, we have introduced and characterized a ubiquitin point mutant capable of conjugating to cognate substrates and incorporating into ubiquitin chains, yet remains refractory to cleavage by DUBs. This provides a unique tool to enable the generation, identification and study of substrates with stabilized ubiquitination states. Previous work by Békés et al. (Bekes et al., 2011) on the related ubiquitin-like molecule SUMO2 showed that mutation in the P4 position of the SUMO cleavage site for deSUMOylating enzymes (SENPs) from glutamine to proline (Supplementary Figure 1A, Q90P, which is also found naturally in the pseudogene, SUMO4 (Bohren et al., 2007)), results in resistance to cleavage by deSUMOylating enzymes, allowing the generation of stabilized SUMO2-conjugates in cells. We then asked whether mutation of the corresponding residue (Leu73) on ubiquitin could affect ubiquitin cleavage reactions by DUBs and we indeed show that it does. Interestingly, in an alanine-scanning mutagenesis study of yeast ubiquitin more than a decade ago, it was shown that UbL73A allows for ubiquitin conjugation; however, the mutant is partially defective in an S. cerevisiae endocytosis-assay (Sloper-Mould et al., 2001). A recent study has also identified bulky Leu73 mutations that differentially affect conjugation and deconjugation activities (Zhao et al., 2012). Furthermore, yeast provided with the UbL73A mutant as the only source of ubiquitin cannot support vegetative growth (Sloper-Mould et al., 2001). It is possible that the Leu73 mutant phenotype of ubiquitin in yeast is a composite of defects in conjugation as well as deconjugation. Leu73 contributes to part of the hydrophobic patch in ubiquitin centered around Ile36, which is utilized by some E3 ligases to synthesize polyubiquitin chains (Plechanovova et al., 2012). Therefore, in accordance with our in vitro E1/E2/E3 conjugation data, it is possible that certain substrates, whose E3 ligases solely rely on ubiquitin Ile36 hydrophobic interactions, would not be efficiently conjugated by UbL73P. This selectivity at the E3 level, together with the selectivity of the E1 enzymes, Ube1 and Uba6, in differentially charging E2 enzymes, suggests that the conjugation of UbL73P in vivo would be skewed towards conjugation pathways that can tolerate it. Nevertheless, those UbL73P conjugates would remain stable and resistant to DUBs in cells, as is the case for mono-ubiquitinated PCNA, the newly identified Ubc13, unknown factor(s) in the telomeric DDR pathway and others.

Increased levels of PCNA mono-ubiquitination by UbL73P expression in a damage-independent manner mimics the phenotype observed for USP1 knock-down (Huang et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2012). USP1 is the only DUB to date shown to remove ubiquitin from PCNA in vivo. This finding reveals the highly dynamic nature of PCNA mono-ubiquitination in undamaged cells by the Rad18-USP1 E3-DUB cycle and underscores the crucial regulatory role of USP1 in maintaining PCNA in an unubiquitinated state. This regulation ensures that PCNA mono-ubiquitination will not serve as a platform to recruit low-fidelity translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases (Lehmann et al., 2007) in the absence of DNA damage. Failure to maintain appropriate PCNA mono-ubiquitination levels could result in increased TLS polymerase recruitment, such as that of polymerase kappa (Jones et al., 2012), which increases genomic instability.

Despite the important role of ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms in DSB repair (Jackson and Durocher, 2013), UbL73P displayed no global defects in DNA repair mechanisms following bleomycin treatment or ionizing radiation, perhaps because UbL73P was incompletely utilized or because the need for deubiquitination was bypassed. However, the phenotype brought about by UbL73P, in the context of the activation of spontenaous DNA damage response in the absence of the shelterin complex at telomeres, suggests that UbL73P is a functional player and results in the Ub-conjugate stabilization of one or more factors that are required for efficient 53BP1 clearance at chromosomal ends. This is in accordance with a recent finding showing that telomeric and genomic DDR pathways are quite different (Cesare et al., 2013): telomeric DDR does not activate checkpoint signaling and could rely on entirely different sets of effector proteins, some of which could be sensitive to stabilized ubiquitination. The telomeric UbL73P phenotype mimics the one observed with the knock-down of BRCC3, which opposes the activity of RNF168 at telomeres (Okamoto et al., 2013). The identity of the ubiquitinated substrate(s) that are responsible for the activation/regulation of telomeric DDR is currently unknown. In the future, it will be important to discern global vs. telomeric ubiquitination substrates in DNA damage response pathways.

In our exploratory UbL73P substrate identification survey, we validated the approach by identifying known ubiquitination sites on PCNA and others (Povlsen et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2008). We also identified several novel ubiquitinated substrates stabilized by UbL73P. We were able to confirm the ubiquitination of Ubc13 on Lys92, a previously indicated site of ISG15 modification (Giannakopoulos et al., 2005). Additionally, we identified the site of ubiquitination on Ube2T, another E2 enzyme that has been previously shown to be ubiquitinated (Machida et al., 2006). Intriguingly, several other E2 Ub-conjugating enzymes were found in our mass spectrometry results. Whether reversible E2 ubiquitination is a regulatory post-translational modification common to a variety of E2 enzymes remains to be determined.

The utility of DUB-resistant ubiquitin tools is highly promising. First, it is possible to ubiquitinate substrates using UbL73P in vitro and assay the stable Ub-conjugate in subsequent binding or affinity purification experiments in search of binding partners. Second, the UbL73P-stabilized ubiquitin chains of a defined linkage could also be utilized to identify substrates modified by a particular ubiquitin chain linkage or identify binding proteins unique to a particular ubiquitin chain linkage. This approach will be most beneficial for chains utilizing hitherto uncharacterized linkages, such as Lys29 and Lys33, and will also allow the purification and identification of ubiquitin receptors that recognize these unique chains. Finally, as unanchored oligomeric ubiquitin chains appear to be stabilized by both UbG76A and by UbL73P, such DUB-resistant ubiquitin mutants have the potential to shed light on the nature and the dynamics of de novo unanchored ubiquitin chain formation, both in resting cells and in a signal inducible manner. This has been a relatively unexplored area of research, as only recently have unanchored ubiquitin chains been implicated in kinase activation (Xia et al., 2009) and in anti-viral immunity (Zeng et al., 2010). As long as the conjugation competency for a particular pathway is adequate, we envision the use of DUB-resistant ubiquitins and other isopeptidase-resistant ubiquitin-like molecules by researchers who seek to interrogate ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like-mediated biological processes in a wide range of experimental settings.

Experimental Procedures

In vitro ubiquitination and deubiquitination reactions

Unless otherwise indicated, ubiquitination and E1- and E2-charging reactions were carried out as previously described (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). Briefly, in 30mM HEPES, pH=7.5, 100mM NaCl and 5mM MgCl2, 20 µM ubiquitin (WT or its mutants) were incubated with E1 and E2 enzymes at 150 nM and 500nM, respectively, in the presence or absence of 2mM ATP for the indicated times at 37°C and boiled immediately in sample buffer (−/+ 5mM DTT for non-reducing/reducing gels) to terminate the reaction. For the deubiquitination assay of Ubc13(Ubc13/Uev1a-heterodimer)-conjugated di-ubiquitin, the ubiquitin assay described above was performed for 1 hour, then the reaction was terminated with 25 mM EDTA for 10 minutes, and diluted (4/5) into a serial-dilution of USP2CD and the mix was incubated for another hour at 37°C. For the single time-point in vitro DUB assays, 2µg wild-type of L73P (non-hydrolyzable, NH) ubiquitin tetramers were cleaved with 100nM DUBs for one hour at 37°C, the analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie-staining. For USP2CD serial dilutions (with 1µg of linear chains or with Ubc13-produced K63-chains or with 10µg total cell lysates), USP2CD was prepared at a starting concentration of 1µM with 1/10-serial-dilution in assay buffer or in the cell lysate with a final concentration of 5mM DTT. Ubiquitination reactions for p53 using E3 ligases were carried out with E3 kits from Boston Biochem according to the protocols described therein, then, where indicated, reactions were quenched with 50mM EDTA and further incubated with 1µM USP2CD for 30min at 37°C.

Cell culture, plasmid transfection, lysate preparation and immunoprecipitation

U2OS and HEK293 cells were maintained as previously described (Huang et al., 2006). Transfections were carried out using Fugene (Promega) or Hiperfect (Qiagen), for plasmids or siRNA oligos, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The siRNA used to knock-down Rad18 has been described previously (Huang et al., 2006). Cells were routinely harvested in PBS and the pellets were frozen at −80°C prior to lysis. Cells were either lysed in denaturing SDS-buffer (100mM Tris, pH=6.8, 2% SDS and 20mM β-Me) for direct analysis by SDS-PAGE or in non-denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris, pH=7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and benzoase (Novagen)) for immuno-precipitations (IPs) and ubiquitin-receptor binding assays.

Ubiquitin-receptor binding assays

Cell lysates prepared under non-denaturing conditions (150 µg) were incubated with 10 µl agarose-conjugated ubiquitin-receptors (RAP80-UIMs or S5a/Angiocidin, Boston Biochem) for 1 hour at 4°C in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH=8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM DTT, supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)), then washed three times in binding buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Plasmids and recombinant protein expression

For the purification of untagged human ubiquitins (linear-di-ubiquitin and mono-ubiquitin mutants), ubiquitin (residues 1–76), was cloned as a His6-SMT3-fusion protein (plasmid is gift from Chris Lima). Briefly, SMT3-Ub proteins were expressed in E.coli codon-plus cells at 30°C for 3 hours by inducing expression with 1mM IPTG. His6-SMT3-Ub proteins were purified by Ni2+-NTA and size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex-200 26/60 column in 20mM Tris, pH=8.0, 350mM NaCl and 1mM β-Me. The purified fusion protein was cleaved overnight at 4°C with Ulp1 at a molar ratio of 1:1000, next, untagged ubiquitin was separated from His6-SMT3 by a final ion-exchange step on a MonoQ 10/10 column. Untagged ubiquitin proteins produced this way have additional SerGly- residues at their N-termini owing to the cloning strategy using BamHI-XhoI. For mammalian expression, ubiquitin (residues 2–76) was subcloned into pcDNA3 with an N-terminal HA-tag using the restriction sites HindIII and XhoI; and has been used as a template to obtain the indicated point-mutants by site-directed mutagenesis. The catalytic domain of human USP2a (residues 259–605) was cloned with a C-terminal His-tag in pET21a and expressed as previously. Briefly, USP2CD was expressed in E.coli codon-plus cells at 30°C for 5 hours by inducing with 1mM IPTG. USP2CD-His was then purified by Ni2+-NTA and size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex-75 26/60 column in 20mM HEPES, pH=7.0, 350mM NaCl and 1mM β-Me, followed by a final ion-exchange step on a MonoS 10/10 column. Recombinant S. pombe E1 (Uba1) was a gift from Shaun K. Olsen, other enzymes have been purchased from Boston Biochem. USP1/UAF1 was purchased from Ubiquigent. All constructs have been verified by sequencing and all recombinant proteins have been aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-ubiquitin (P4D1, sc-8017, Santa Cruz), anti-His (mouse-monoclonal, Genscript), anti-HA (Mono HA.11, MMS-101R, Covance), anti-PCNA (PC10, sc-56, Santa Cruz), anti-MCM6 (A300-194A-2, Bethyl), anti-Rad18 (A301–340A, Bethyl), anti-MCM4 (A300-193A, Bethyl), anti-myc (c-3956, Sigma), anti-GFP (B-2, sc-9996, Santa Cruz), anti-p53 (Boston Biochem).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were grown and processed in 8-well Lab-Teks II ChamberSlideTM System slides from Nunc (Naperville, IL). For the bleomycin recovery experiment, cells were treated with 5µg/ml bleomycin sulfate (Calbiochem) for 1 hour at 37°C, then, where indicated, recovered in full media for 24 hours, and fixed using methanol-fixation and stained with anti-HA and anti-53BP1 antibodies. GFP-Pol-eta nuclear foci formation was detected after methanol fixation and cells were stained with anti-GFP for 2 hours at room temperature. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit. Slides were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (VectorLaboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were deconvolved using Softworx software (Applied Precision). The images were opened and then sized and placed into Figures using imageJ. At least 50 GFP/HA-positive nuclei were counted per chamber and were quantified for containing more than 10 nuclear GFP-eta foci. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean, n=3.

MEFs

MEFs from E13.5 embryos obtained from crosses between Rosa26 CRE-ER Mice (Jackson) and mice carrying a conditional TRF2 allele (Celli and de Lange, 2005) were immortalized at passage 2 with pBabeSV40LT. Ubiquitin-HA constructs were introduced by retroviral infection using the following constructs: pLPC-HA-Ub and pLPC-HA-Ub-L73P. IR treatments, metaphase spreads and FISH/IF co-staining were performed as described previously (Okamoto et al., 2013); 53BP1 was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Novus, NB 100–304). Experiments were repeated in triplicates and 53BP1 foci were scored in at least 200 cells for each experiment. Data reported are averages of three independent experiments error bars represent standard deviation.

Stable cell lines

HeLa cells expressing doxycycline-inducible FLAG-Ub-WT and FLAG-Ub-L73P were generated using Flippase (Flp) recombination target (FRT)/Flp-mediated recombination technology in HeLa-T-rex Flp-in cells, as described previously (Tighe et al., 2008). Cells were induced with 1 µ g/ml doxycycline for the indicated times to induce transgene expression. For a medium scale mass-spec study, Flp-in UbL73P cells (36×15cm dishes) were grown to ∼60% confluency and induced with 1µg/ml doxycycline for 48 hours. Cells were briefly pelleted and frozen at −80°C until further processing.

FLAG immune-precipitation of Flp-in UbL73P cells

Cell pellets were lysed in mRIPA buffer (20mM Tris, pH=7.5, 1% NP-40, 0.5% CHAPS, 0.1% SDS and 150mM NaCl) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1U/µl benzoase (Novagen), for 1 hour on ice. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the supernatant was incubated 100µg M2-conjugated (anti-FLAG) magnetic DynaBeads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at 4°C. The beads were extensively washed in mRIPA buffer, then in 100mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8, and immediately processed for mass-spectrometry-grade trypsin digest.

Mass-spectrometry

Immunoprecipitated proteins were reduced with the addition of 0.2 M dithiothreitol at pH 8 for 1 hour at 57 ˚C and subsequently alkylated using 0.5 M iodoacetic acid at pH 8 for 45 minutes in the dark at RT. The samples were proteolytically digested with trypsin (Promega) at a 1:20 enzyme to substrate ratio overnight with gentle shaking at RT. The resulting peptide mixture was removed from the beads and adjusted to pH 4 with trifluoroacetic acid prior to desalting using a C18 Stage tip procedure, as previously described (Cotto-Rios et al., 2012; Rappsilber et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2012). The desalted peptide mixture was concentrated in a SpeedVac concentrator to remove organic solvents. A 10th of the peptide mixture was loaded onto a Acclaim PepMap 100 precolumn (75 µm × 2 cm, C18, 3 µm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific (Thermo Scientific) that was connected to a EASY-Spray , PepMap RSLC column (75 µm × 25 cm, C18, 2 µm, 100 Å Thermo Scientific (Thermo Scientific) with a 5 µm emitter using the autosampler of a EASY-nLC 1000 (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were gradient eluted from the column directly into a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) using a 120 min gradient from 2% solvent B to 40% solvent B. Solvent A was 2% acetonitrile in 0.5 % acetic acid and Solvent B was 90% acetonitrile in 0.5% acetic acid. High resolution MS1 spectra were acquired with a resolution of 70,000, an AGC target of 1e6, with a maximum ion time of 120 ms, and scan range of 400 to 1500 m/z. Following each MS1 twenty data-dependent high resolution HCD MS2 spectra were acquired. All MS2 spectra were collected using the following instrument parameters: resolution of 17,500, AGC target of 5e4, maximum ion time of 250 ms, one microscan, 2 m/z isolation window, fixed first mass of 150 m/z, 30 second exclusion list and NCE of 27.

Database search

All MS2 spectra were searched against a uniprot human database using Sequest via Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Scientific). For the search trypsin was indicated as the enzyme, precursor mass tolerance was set to +/−10 ppm, and fragment ion mass tolerance to +/−0.02 Da. Carboxymethylation of Cys was searched as a static modiciation. The following variable modifications were also searched: diglycylation of Lys, deamidation of Gln and Asp, and oxidation of Met. Peptides identified as having a diglycylated lysine were manually validated.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

UbL73P ubiquitin conjugates are not deubiquitinated by various DUB family members

Expression of DUB-resistant ubiquitin in cells stabilizes mono-ubiquitinated PCNA

Expression of UbL73P reduces the clearance of 53BP1 foci at unprotected telomeres

Proteomic survey of UbL73P-expressed cells identifies new ubiquitinated substrates

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kristin Burns-Huang for critically reading the manuscript, members of the Lima, Sfeir, Smith, Reinberg and Huang labs for reagents, resources and discussions and Shaun K. Olsen for the S. pombe E1 and for assistance with structure-based modeling. We express our gratitude to Chris Lima for hosting M.B. during the hurricane Sandy lab relocation at NYU. M.B. is a recipient of an NRSA postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM100598-01) and research in the Huang lab is supported by grants from the NIH (GM084244) and from ACS (RSG-12-158-01-DMC). M.B., with input and help from T.T.H., conceived the project, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. B.B. and F.M. synthesized the wild-type and (non-hydrolyzable, NH) Ub tetramers and contributed Figure 1G; K.O. and E.L.D. performed and analyzed the experiments with the TRF2F/F cells (Figure 4C–E and Supplementary Figure 4B–C); M.J.J. generated the Flp-in stable cells (used in Figure 5); S.B.C. cultured Flp-in cells and carried out the TNF-□ experiment (Supplementary Figure 4A) and aided in mass-spectrometry preparation. Protein identification by mass-spectrometry was carried out by J.C–L and B.U.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

B.B. and F.M. are employees of Boston Biochem, Inc. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bekes M, Prudden J, Srikumar T, Raught B, Boddy MN, Salvesen GS. The dynamics and mechanism of sumo chain deconjugation by SUMO-specific proteases. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10238–10247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.205153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren KM, Gabbay KH, Owerbach D. Affinity chromatography of native SUMO proteins using His-tagged recombinant UBC9 bound to Co2+-charged talon resin. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;54:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare AJ, Hayashi MT, Crabbe L, Karlseder J. The telomere deprotection response is functionally distinct from the genomic DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2013;51:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotto-Rios XM, Bekes M, Chapman J, Ueberheide B, Huang TT. Deubiquitinases as a signaling target of oxidative stress. Cell reports. 2012;2:1475–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayal S, Sparks A, Jacob J, Allende-Vega N, Lane DP, Saville MK. Suppression of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 causes the accumulation of unanchored polyubiquitin and the activation of p53. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5030–5041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448:1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou H, Buetow L, Sibbet GJ, Cameron K, Huang DT. BIRC7-E2 ubiquitin conjugate structure reveals the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by a RING dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:876–883. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A, Avvakumov G, Tong J, Fan Y, Zhao Y, Alberts P, Persaud A, Walker JR, Neculai AM, Neculai D, et al. A strategy for modulation of enzymes in the ubiquitin system. Science. 2013;339:590–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1230161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos NV, Luo JK, Papov V, Zou W, Lenschow DJ, Jacobs BS, Borden EC, Li J, Virgin HW, Zhang DE. Proteomic identification of proteins conjugated to ISG15 in mouse and human cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins RR, Ellison KS, Ellison MJ. Expression of a ubiquitin derivative that conjugates to protein irreversibly produces phenotypes consistent with a ubiquitin deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8807–8812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Li P, Li M, Li W, Yao T, Wu JW, Gu W, Cohen RE, Shi Y. Crystal structure of a UBP-family deubiquitinating enzyme in isolation and in complex with ubiquitin aldehyde. Cell. 2002;111:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Nijman SM, Mirchandani KD, Galardy PJ, Cohn MA, Haas W, Gygi SP, Ploegh HL, Bernards R, D'Andrea AD. Regulation of monoubiquitinated PCNA by DUB autocleavage. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:339–347. doi: 10.1038/ncb1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Durocher D. Regulation of DNA damage responses by ubiquitin and SUMO. Mol Cell. 2013;49:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Li X, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Dual E1 activation systems for ubiquitin differentially regulate E2 enzyme charging. Nature. 2007;447:1135–1138. doi: 10.1038/nature05902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MJ, Colnaghi L, Huang TT. Dysregulation of DNA polymerase kappa recruitment to replication forks results in genomic instability. EMBO J. 2012;31:908–918. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR. Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2004;14:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Chen J, Yu X. Ubiquitin-binding protein RAP80 mediates BRCA1-dependent DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1139621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D, Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann AR, Niimi A, Ogi T, Brown S, Sabbioneda S, Wing JF, Kannouche PL, Green CM. Translesion synthesis: Y-family polymerases and the polymerase switch. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida YJ, Machida Y, Chen Y, Gurtan AM, Kupfer GM, D'Andrea AD, Dutta A. UBE2T is the E2 in the Fanconi anemia pathway and undergoes negative autoregulation. Mol Cell. 2006;23:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Bartocci C, Ouzounov I, Diedrich JK, Yates JR, 3rd, Denchi EL. A two-step mechanism for TRF2-mediated chromosome-end protection. Nature. 2013;494:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature11873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SK, Lima CD. Structure of a ubiquitin E1-E2 complex: insights to E1-E2 thioester transfer. Mol Cell. 2013;49:884–896. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. In vitro reconstitution of SCF substrate ubiquitination with purified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005;398:143–158. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plechanovova A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povlsen LK, Beli P, Wagner SA, Poulsen SL, Sylvestersen KB, Poulsen JW, Nielsen ML, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Choudhary C. Systems-wide analysis of ubiquitylation dynamics reveals a key role for PAF15 ubiquitylation in DNA-damage bypass. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1089–1098. doi: 10.1038/ncb2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1896–1906. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D227–D233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renatus M, Parrado SG, D'Arcy A, Eidhoff U, Gerhartz B, Hassiepen U, Pierrat B, Riedl R, Vinzenz D, Worpenberg S, et al. Structural basis of ubiquitin recognition by the deubiquitinating protease USP2. Structure. 2006;14:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper-Mould KE, Jemc JC, Pickart CM, Hicke L. Distinct functional surface regions on ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30483–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhian B, Shao G, Lilli DR, Culhane AC, Moreau LA, Xia B, Livingston DM, Greenberg RA. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites. Science. 2007;316:1198–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1139516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KD, Tashayev VL, O'Connor LB, Larsen CN, Kasperek E, Pickart CM. Metabolism of the polyubiquitin degradation signal: structure, mechanism, and role of isopeptidase T. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14535–14546. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Chapman JR, Wang L, Harris TE, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Fu Z. Intestinal cell kinase (ICK) promotes activation of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) through phosphorylation of Raptor Thr-908. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12510–12519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia ZP, Sun L, Chen X, Pineda G, Jiang X, Adhikari A, Zeng W, Chen ZJ. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature. 2009;461:114–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Sun L, Jiang X, Chen X, Hou F, Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Reconstitution of the RIG-I pathway reveals a signaling role of unanchored polyubiquitin chains in innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:315–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhou L, Rouge L, Phillips AH, Lam C, Liu P, Sandoval W, Helgason E, Murray JM, Wertz IE, et al. Conformational stabilization of ubiquitin yields potent and selective inhibitors of USP7. Nature chemical biology. 2013;9:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Bhuripanyo K, Schneider J, Zhang K, Schindelin H, Boone D, Yin J. Specificity of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade for ubiquitin C-terminal sequences identified by phage display. ACS chemical biology. 2012;7:2027–2035. doi: 10.1021/cb300339p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Zhu P, Wang J, Pascual G, Ohgi KA, Lozach J, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Histone H2A monoubiquitination represses transcription by inhibiting RNA polymerase II transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.