Abstract

Objective

This study has two main objectives. The first is to detail the prevalence rates of three key treatment modalities reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison participants over a decade of follow-up. The second is to determine time-to-cessation and time-to resumption of these three treatment modalities reported by patients with borderline personality disorder.

Methods

The treatment history of 290 reliably diagnosed inpatients with borderline personality disorder and 72 axis II comparison participants was assessed using an interview of proven reliability during their index admission. Treatment history was reassessed at five contiguous two-year follow-up periods.

Results

In terms of prevalence rates, there was a significant decrease in the percentage of patients with borderline personality disorder (and axis II comparison participants) participating in the three treatment modalities studied. In terms of time-to-cessation and resumption, 52% of patients with borderline personality disorder stopped individual therapy and 44% stopped taking standing medications for a period of two years or more. However, 85% of those who had stopped psychotherapy resumed it and 67% of those who stopped taking medications later resumed taking them. In contrast, 88% had no hospitalizations for at least two years but almost half of these patients were subsequently rehospitalized.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results suggest that patients with borderline personality disorder tend to use outpatient treatment without interruption over prolonged periods of time. They also suggest that inpatient treatment is used far more intermittently and by only a relative small minority of those with borderline personality disorder.

Clinical experience suggests that individuals with borderline personality disorder commonly report being in psychotherapy and taking standing psychotropic medications over substantial periods of time. Clinical experience also suggests that patients with borderline personality disorder are frequently rehospitalized. However, only two longitudinal studies have prospectively examined the long-term course of the psychiatric treatment received by these patients. In the first of these studies [1], treatment utilization of patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison participants was studied over six years of prospective follow-up in the McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD). It was found that prevalence rates of individual therapy, standing medications, and psychiatric hospitalizations declined significantly for those in both study groups but remained significantly higher among patients with borderline personality disorder than axis II comparison participants. Perhaps most striking was the finding that 70% of patients with borderline personality disorder participated in individual therapy and 70% took standing medications in all three follow-up periods.

In the second longitudinal study (the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study or CLPS), the treatment use of patients with borderline personality disorder was compared to that of patients with major depressive disorder and no personality disorder over the course of three years [2]. It was found that patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely to be in individual therapy, have had a medication consultation, and been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons than those with major depressive disorder.

The current study, which is an extension of the MSAD study mentioned above, has two purposes. The first is to describe the prevalence of three key treatment modalities reported by a large and well-defined sample of patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison participants over 10 years of prospective follow-up. The second purpose is to detail time-to-cessation and time-to-resumption of these three forms of treatment by patients with borderline personality disorder.

Methods

Sample

The methodology of this study has been described in detail elsewhere [3]. Briefly, this study was approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject after careful explanation of what the study involved and before any study procedures were administered.

All participants were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts who were admitted and interviewed between 1992–1995. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she fulfilled the following inclusion criteria. He or she was between the ages of 18–35; had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and lastly, was fluent in English.

Procedures

Each patient met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough diagnostic assessment. Three semistructured diagnostic interviews were administered. These diagnostic interviews were the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) [4], the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) [5] and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) [6]. The interrater and test-retest reliability of all three of these measures have been found to be good-excellent [7,8].

Treatment history was assessed using the Background Information Schedule (BIS) – a semi-structured interview designed to assess the psychosocial functioning and treatment histories of patients with borderline personality disorder and patients with other axis II disorders. The interrater and test-retest reliability and the concurrent validity of the BIS have been found to be good-excellent [9].

At each of five follow-up waves, separated by 24 months, psychiatric treatment use was reassessed via interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by staff members blind to baseline diagnoses. After informed consent was obtained, the follow-up analog to the BIS was administered--the Revised Borderline Follow-Up Interview (BFI-R). Good-excellent follow-up interrater reliability (within one generation of follow-up raters) and follow-up longitudinal reliability (from one generation of raters to the next) were found for this interview as well [9].

Statistical Methods

Generalized estimating equations, with diagnosis and time as main effects, were used in longitudinal analyses of prevalence data. Tests of diagnosis by time interactions were conducted. These analyses modeled the log prevalence, yielding an adjusted relative risk ratio (RRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for diagnosis and time. Gender was also included in these analyses as a covariate as patients with borderline personality disorder were significantly more likely than axis II comparison participants to be female. Alpha was set at the p<.05 level, two-tailed.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess the time-to-cessation of treatment and time-to-resumption of treatment for the three treatments studied: individual therapy, standing medications, and psychiatric hospitalizations. We defined time-to-cessation of treatment of each of the treatment modalities studied as the time until the follow-up period at which cessation of treatment was first achieved, i.e. the subject stopped participating in that modality. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons (in the particular treatment at baseline) first stopping one of the treatment modalities studied during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first stopping during the second follow-up period, etc. We defined time-to-resumption of treatment in a somewhat different manner (i.e., the number of years after a person had stopped a treatment that he or she went back into that treatment). Thus, times for this outcome were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first stopping that form of treatment.

Results

Baseline sample description

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for borderline personality disorder). Of these 72 comparison participants, 4% met DSM-III-R criteria for an odd cluster personality disorder, 33% met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxious cluster personality disorder, 18% met DSM-III-R criteria for a nonborderline dramatic cluster personality disorder, and 53% met DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the DIPD-R as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported before [3]. Briefly, 77% (N=279) of the participants were female and 87% (N=315) were white, 5.5% were African-American, 2.5% were Hispanic, 2% Asian, and 3% other or biracial. The average age of the participants was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (where 1=highest and 5=lowest) [10], and their mean GAF score was 39.8 (SD=7.8) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood).

In terms of continuing participation, 90% (N=309) of surviving patients were reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves. More specifically, 92% of surviving patients with borderline personality disorder (249/271) and 85% of surviving axis II comparison participants (60/71) were evaluated six times (baseline and five follow-up periods).

Mental health service use over time

Table 1 details the prevalence rates of three treatment modalities used by patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison participants over 10 years of prospective follow-up. As can be seen, a significantly higher percentage of patients with borderline personality disorder than axis II comparison participants reported taking standing medications over the 10 years of follow-up. Specifically, these patients were about 29% more likely to be taking standing medications over the 10 years of follow-up than axis II comparison participants. When all participants were considered together, the rate of those taking psychotropic medications declined significantly over time, with a relative decrease of approximately 21% ([1−.79]×100%).

Table 1.

Psychiatric Treatment Received by Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Axis II Comparison Participants Over 10 Years of Prospective Follow-up

| Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=290) |

2 Yr FU (N=275) |

4 Yr FU (N=269) |

6 Yr FU (N=264) |

8 Yr FU (N=255) |

10 Yr FU (N=249) |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Individual Therapy |

279 | 96 | 257 | 94 | 211 | 78 | 197 | 75 | 186 | 73 | 181 | 73 |

| Standing Medication(s) |

244 | 84 | 237 | 86 | 204 | 76 | 187 | 71 | 180 | 71 | 179 | 72 |

| Psychiatric Hospitalizations |

228 | 79 | 164 | 60 | 97 | 36 | 86 | 33 | 71 | 28 | 72 | 29 |

| Axis II Comparison Participants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (N=72) |

2 Yr FU (N=67) |

4 Yr FU (N=64) |

6 Yr FU (N=63) |

8 Yr FU (N=61) |

10 Yr FU (N=60) |

Relative Risk Ratio Diagnosis Time Interaction |

95% CI Diagnosis Time Interaction |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Individual Therapy |

62 | 86 | 59 | 88 | 42 | 66 | 40 | 64 | 28 | 46 | 27 | 45 | 1.05 .49 1.44 |

.98–1.12 .38–.63 1.11–1.88 |

| Standing Medication(s) |

44 | 61 | 52 | 78 | 34 | 53 | 34 | 54 | 30 | 49 | 31 | 52 | 1.29 .79 |

1.13–1.48 .73–.86 |

| Psychiatric Hospita- lizations |

36 | 50 | 15 | 22 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 7 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 1.65 .09 3.21 |

1.30–2.10 .05–.16 1.66–6.23 |

P-level results for diagnosis were: individual therapy non-significant at baseline; standing medications <0.001; hospitalization <0.001

P-level results for time were all <.001

P-value for interaction term for individual therapy .006; hospitalization .001

However as significant interactions between diagnosis and time were found for individual therapy and psychiatric hospitalizations, the explanation of these results is more complicated. In terms of individual therapy, about 96% of patients with borderline personality disorder (and about 86% of axis II comparison participants) reported having been in individual therapy at the time of their index admission. By the time of their 10-year follow-up, these prevalence rates had declined to about 73% and 45% respectively. The RRR of 1.05 for the effect of diagnosis indicates that patients with borderline personality disorder were about 5% more likely to be in individual therapy than axis II comparison participants at baseline. The RRR of .49 for the effect of time indicates that the chance of participating in individual therapy over the course of the study for axis II comparison participants decreased by 51% ([1−.49]×100%) from baseline to 10-year follow-up. Finally, the significant interaction between diagnosis and time indicates that the corresponding relative decline from baseline to 10-year follow-up is approximately 29% ([1 − .49×1.44]×100%) for patients, i.e., the rate of decline is significantly smaller, approximately 30% versus 50%, for patients with borderline personality disorder than axis II comparison participants.

In terms of psychiatric hospitalizations, about 79% of patients with borderline personality disorder (and 50% of axis II comparison participants) reported having been hospitalized prior to their index admission. By the time of their 10-year follow-up, these prevalence rates had declined to about 29% and 3% respectively. The RRR of 1.65 for the effect of diagnosis indicates that patients with borderline personality disorder were about 65% more likely to have prior hospitalizations than axis II comparison participants at baseline. The RRR of .09 for the effect of time indicates that the chance of being hospitalized over the course of the study for axis II comparison participants decreased by 91% (1−.09×100%). Finally, the significant interaction between diagnosis and time indicates that the relative decline from baseline to 10-year follow-up is approximately 71% ([1−.09×3.21]×100%) for patients with borderline personality disorder, i.e., the rate of decline is significantly smaller, approximately 70% versus 90%, for patients with borderline personality disorder than for axis II comparison participants.

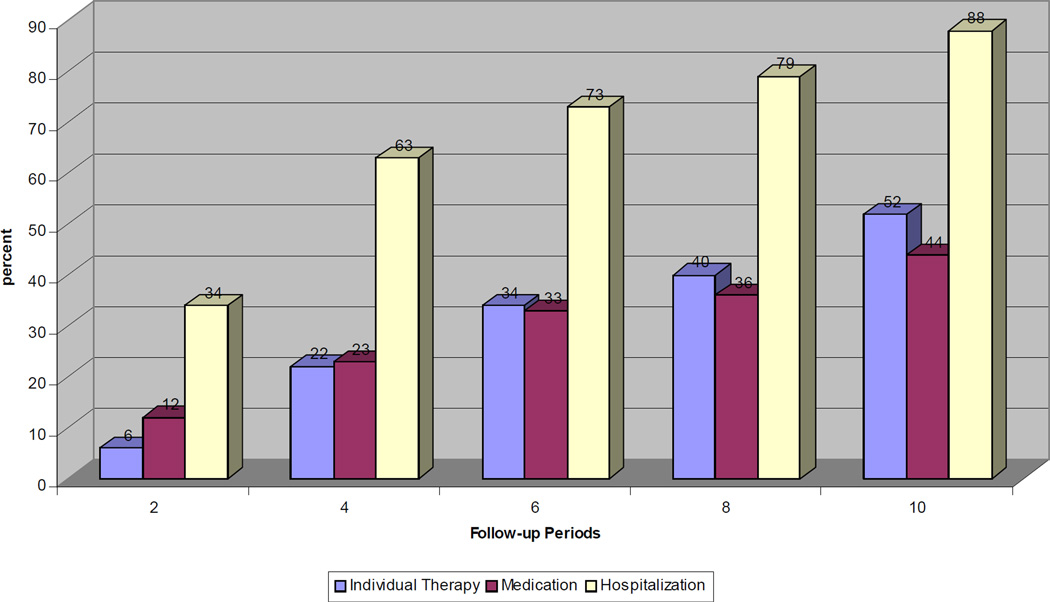

Figure 1 details time-to-cessation for each of the three treatment modalities studied. As can be seen, about 52% of patients with borderline personality disorder who were in individual therapy at baseline ceased being in therapy by the time of the 10-year follow-up (N=84). As can also be seen, 44% who were taking standing medication at baseline ceased using medication (N=89). As noted above, all 290 patients with borderline personality disorder were hospitalized at baseline. At the 10-year follow-up, nearly 90% had had at least one two-year period without a psychiatric hospitalization (N=178). (Note that rates of treatment cessation cannot be determined using the numbers presented above because of censoring [i.e., participants lost to follow-up].)

Figure 1.

Time-to-cessation of Individual Therapy, Standing Medication, and Psychiatric Hospitalization among Borderline Patients over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up

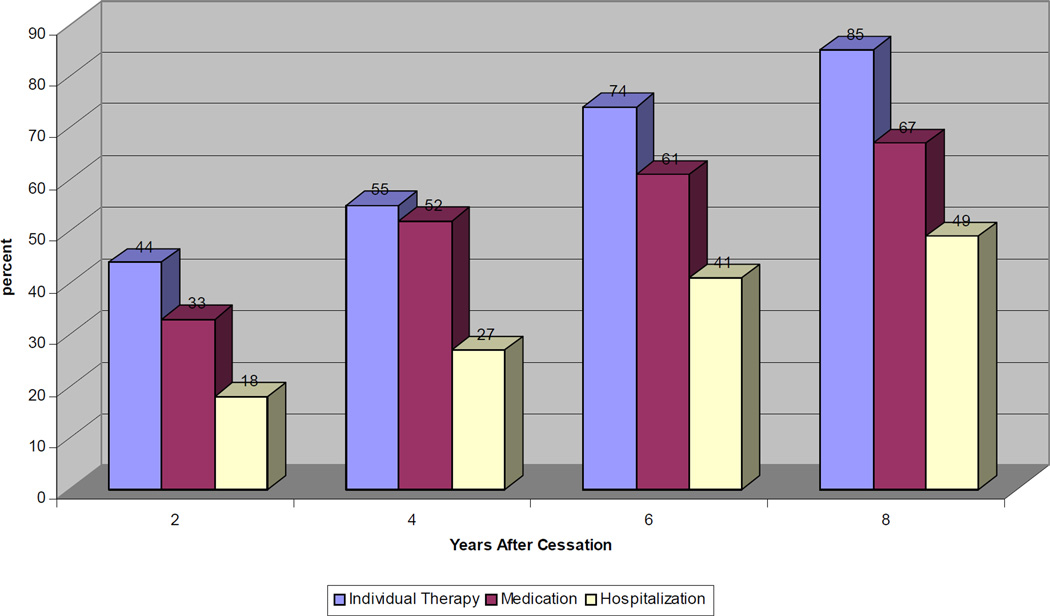

Figure 2 details time-to-resumption of each of the three treatment modalities studied. As can be seen, 85% of patients with borderline personality disorder who reported having stopped individual therapy resumed therapy at a subsequent follow-up period (N=62). As can also be seen, 67% of the patients who stopped taking standing medications resumed pharmacological treatment (N=44). In addition, almost half of the patients (49%) who had not been hospitalized for at least one follow-up period of two years in length were rehospitalized by the 10-year follow-up (N=59). (Note that rates of treatment resumption cannot be determined using the numbers presented above because of censoring [i.e., participants lost to follow-up].)

Figure 2.

Time-to-resumption of Individual Therapy, Standing Medication, and Psychiatric Hospitalization among Borderline Patients over Ten Years of Prospective Follow-up

Discussion

Four main findings have emerged from the results of this study. The first finding is that the prevalence of each of the three treatment modalities studied declined significantly over time for patients with borderline personality disorder (and axis II comparison participants). More specifically, the prevalence of any individual therapy declined about 29% for patients with borderline personality disorder, the prevalence of standing medications declined 21%, and the prevalence of psychiatric hospitalizations declined approximately 71%. These findings are consistent with and extend the findings of our six-year follow-up study of this sample [1].

The second finding is that both the use of standing medications and psychiatric hospitalizations (but not individual therapy) were significantly more common in patients with borderline personality disorder than axis II comparison participants. More specifically, patients with borderline personality disorder were 29% more likely to be on standing medication, 65% more likely to be hospitalized for psychiatric reasons at baseline but only 5% more likely to be in individual therapy at baseline. These findings too are consistent with and extend the findings of our six-year follow-up study of this sample [1].

The third finding is that about half of those patients with borderline personality disorder in individual psychotherapy or taking standing medications at baseline stopped these outpatient treatments by the time of the 10-year follow-up. In addition, nearly 90% of patients with borderline personality disorder reported not having been rehospitalized by the 10-year follow-up. This is a new finding and seems to demonstrate a specific pattern in the long-term treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a more continuous use of outpatient treatment and a decline in inpatient treatment. It is interesting to note that the major decrease in these two outpatient treatments took place by the fourth year after their index hospitalization and then remained rather stable throughout the remaining six years of follow-up.

The fourth finding is that resuming each of the treatment modalities studied is common. More specifically, 85% of patients with borderline personality disorder who terminated individual therapy later went back into therapy. In a similar vein, 67% of patients with borderline personality disorder who had stopped using standing medication later resumed psychopharmacological treatment. In addition, nearly 50% of those who had ceased being hospitalized for a period of at least two years were later re-hospitalized. This set of findings is also new and is consistent with the prior finding that outpatient treatment modalities are used more consistently than inpatient treatment. It is not clear why resumptions of outpatient treatment are so common but they could be due to residual borderline symptoms, ongoing axis I disorders, psychosocial dysfunction, or some combination of these factors.

Almost none of the patients with borderline personality disorder in the study had ever been in a treatment specifically designed for those with borderline personality disorder. Whether the results of the study would have been different if a substantial percentage of those with borderline personality disorder had participated in one of the psychotherapeutic approaches specifically developed for the treatment of borderline personality disorder (dialectical behavioral treatment or DBT [11], mentalization-based treatment or MBT [12], transference-focused psychotherapy or TFP [13], and schema-focused therapy or SFT [14]) is impossible to determine.

This study has two main limitations. The first is that all of the patients were seriously ill inpatients at the start of the study. Thus, it is difficult to know if these results would generalize to a less disturbed group of patients with borderline personality disorder. The second is that most of the information on treatment history was based on self-report. However, we were able to use the hospital’s electronic medical record system to validate the number and length of inpatient stays for those patients hospitalized at McLean.

Conclusions

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that patients with borderline personality disorder tend to use outpatient treatment without interruption over prolonged periods of time. They also suggest that inpatient treatment is used far more intermittently and by only a relative small minority of those with borderline personality disorder.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Fellowship Persönlichkeitsstörungen by the Gesellschaft zur Erforschung und Therapie von Persönlichkeitsstörungen (GePs) e.V. / Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH and by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169.

References

- 1.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and Axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:28–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender DS, Skodol AE, Pagano ME, et al. Prospective assessment of treatment use by patients with personality disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:254–257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanarini MC, Gunderson J, Frankenburg FR, et al. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, et al. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: interrater and test-retest reliability. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al. Psychosocial functioning of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:19–29. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.1.19.62178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman AW, Fonagy P. The effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, et al. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:922–928. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven S, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:649–658. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]