Abstract

T cell activation depends upon extracellular ligation of the T cell receptor (TCR) by peptide–MHC complexes in a synapse between the T cell and an antigen presenting cell (APC), assembly of signalling complexes with the adaptor protein linker of activated T cells (LAT) and filamentous actin (f-actin) dependent TCR cluster formation. Recent progress in each of these areas, made possible by the emergence of new techniques, has forced us to rethink our assumptions and consider some radical new models. The topics include the receptor interaction parameters governing T cell responses and the mechanism by which LAT is recruited to the TCR signalling machinery. This is an exciting time in T cell biology and further innovation in imaging and genomics is likely to lead to a greater understanding of how T cells are activated.

Introduction

The T cell synapse is an ultrasensitive system capable of detecting single peptide–MHC complexes 1. Thus, it is natural that interdisciplinary studies of T cell activation are turning to new tools that provide access to the location and/or activity of single molecules or nanoscale assemblies to gain further insight into the underlying mechanisms. These approaches are generating several unexpected results. It had been unclear how the TCR–peptide–MHC interaction controls signalling decisions, but direct measurements of two-dimensional (2D) kinetic rates by two groups by different methods indicate that the 2D on-rate is the dominant parameter that governs biological effects of TCR ligation 2, 3. Electron microscopy and single molecule methods had been used to develop models of T cell signalling in which signalling complexes would be assembled by rearrangement of nanoscale protein islands within the plasma membrane 4, but work from two groups focusing on individual signalling events argues that TCR and LAT come together through a process of sub-synaptic vesicle docking, which has profound implications for the compartmentalization of signalling 5, 6. More and more information is being gained from advanced super-resolution imaging (BOX 1), but the interpretation of the data is complex and there is much still to learn. We and others had argued that the centre of the T cell synapse is a site where TCR signalling ends. While this is often true in the conventional sense, a new study demonstrates that TCRs are packaged into nanoscale exosomes that can target antigen-presenting cells to modify gene expression though a form of intercellular signalling 7. Here, we review recent findings on the functional organization of the T cell synapse and, in particular, highlight the emerging role of new techniques that allow the detection of single events.

Box 1. New techniques for visualizing immunological synapses.

Supported planar bilayer models

An artificial lipid bilayer is formed onto a glass coverslip. The protein of interest can be tethered on the lipid in a quantitative manner. This is relatively physiological way to present purified ligands for single molecule measurements and the detection of SSVs. This technique as the disadvantage of the glass rigidity and opposite of the APC the ligand for the cell are not link to cellular component like cytosqueleton.

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM)

A laser beam is reflected off of the interface between the coverslip and the media/cell. This generates an evanescent wave that penetrates less than 200 nm into the sample and and is ideal for single fluorophore imaging. Thanks to this technique we have a great view of what is happening on the cell surface and it can be linked with FRET, PALM and STORM. But is can not “see” what is happening inside the cell.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)

A technique that is used to measure proximity between fluorophores on the scale of 1-10 nm. It can be applied at the single molecule level and is particularly powerful when combined with atomic level structural information.

Membrane sheet electron microscopy

A method in which a cell is attached to a surface firmly and then “unroofed” to leave the membrane on the substrate and simultaneously fixed to preserve the structures for immunostaining and electron microscopy. It is a very nice technique to visualise with great resolution the cell surface. But as it needs fixation and a lot of processes on the cells, this technique could produce some artefact. More over it will be impossible with to have any dynamics information.

PALM/STORM

A method by which a pattern of fluorophores too crowded for single fluorophore imaging is reconstructed by many cycles of photoactivation/photoconversion and single molecule imaging with ∼20 nm or better resolution. It can have a good advantage of keeping the cell intact (especially for PALM). Live imaging is starting to appear but the time resolution is still poor. Thank to the combination of Interferometric super-resolution fluorescence microscopy with PALM/STORM it is now possible to have a super-resolutioon in 3D.

Interferometric super-resolution fluorescence microscopy

The wave character of photons allows their detection by three cameras through two objectives to capture interference effects and generate very high-resolution three-dimensional location maps of single fluorescent molecules.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FSC)

A method that uses a fixed laser beam focused into a sample to collect fluorescence at a high rate. Autocorrelation analysis allows determination of the number of diffusing particles and their diffusion coefficient. If two channels of data are collected then the cross-correlation also addresses the degree of correlated movement of two different diffusing particles. This shows only correlation with two molecules but can not address their behaviour within the rest of the cell.

Atomic force microscopy

An instrument that uses a cantilever and laser measurement system to determine the position of a sharp probe with a tip a few atoms thick. The system can measure height with sub-nanometre precision and measurements can be guided by confocal microscopy.

Stimulated Emission Depletion microscopy (STED) microscopy

This technique use tow laser the first on is exiting the fluorophores onto the sample, the second in donut shape deplete the fluorescence from the fluorophores that are away from the centre of illumination of the first laser. This can be combined with Interferometric super-resolution fluorescence microscopy to obtain 3D super-resolution.

Structured illumination microscopy (SIM)

SIM is based on the used of a grid to create several interference patterns on the sample. The different images called moiré image are used to reconstruct a final high-resolution image.

Synapse orientation by optical tweezers

In order to visualise the synapse interface at high speed and with a high 2d resolution, Oddos et al use optical tweezers to manipulate the cell conjugate in order to orientate the synapse in the imaging plane of a confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscope 111. This avoid the use of an en face 3D reconstruction of the interface, so it increase the resolution and allow high speed imaging of the contact site.

The Immunological synapse

The context for T cell recognition of antigen is the T cells synapse, the prototypic immunological synapse 8-10. Immunological synapses, and the related kinapses formed by moving cells, have been reviewed extensively 11-13, but we briefly introduce the structure here as it provides a spatial context for our subsequent discussions of controversial or recent findings 2, 3, 5-7. To organize our review around these findings, the immunological synapse can be considered to have three functional layers (Figure 1A), focused on receptor interactions, signal transduction and cytoskeletal transport, as has been illustrated recently for integrin-based focal adhesions 14. These layers provide a true 3rd dimension to the typical consideration of lateral organization of the immunological synapse into supramoleclar activation clusters.

Figure 1.

A The three layers on the T cell side of the immunological synapse are pictured here : receptor layer (TCR complex, CD4/CD8, CD28, LFA1), signalling layer (LCK, ZAP70, ITK, PLCγ) and the cytoskeleton layer (talin, vinculin, FAK/PYK2, paxillin and actin). The adaptor protein LAT is shown attached to the plasma membrane and anchored to vesicles as discussed in the text. B. The supramolecular clusters of an immunological synapse. TCR/cSMAC core (red), CD28/cSMAC periphery (green) and LFA-1/pSMAC (purple). The entire contact area is outlined, and the yellow color represents f-actin, which forms dynamic protrusions that move around the cell periphery (dSMAC) in a radial wave. Each SMAC contains hundreds to thousands of receptors and the dSMAC is the site in which TCR microclusters are first detected.

The receptor interaction layer

This layer includes TCRs, adhesion molecules, co-stimulatory molecules and co-receptors. Every TCR that has been selected as recognizing an agonist ligand can be tested against panels of MHC molecules associated with mutated peptides to identify a spectrum of weak agonist, antagonist and co-agonist ligands 15. Many such peptide series have been generated and characterized, but on the basis of kinetic measurements in solution there is little consensus except that most TCRs recognize agonist peptide–MHC complexes with dissociation constants in the range of 1-50 μM 15, 16. This indicates that solution interaction parameters can't explain the subtleties of TCR ligand discrimination. Adhesion receptors can be defined in this context as receptors that function in adhesion contexts beyond antigen recognition 17. For example, the integrin leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1) functions as an adhesion molecule for circulating leukocytes in the vasculature independent of antigen recognition. Adhesion receptors can also be defined based on peptide–MHC-independent contributions to the interaction between a T cell and a potential antigen-presenting cell (APC). For example, the CD2–CD58 interaction mediates the antigen-independent interaction of cytotoxic T cells with target cells. Co-stimulatory proteins can be defined as having a positive or negative role in the regulation of TCR-mediated signals with little or no function outside of the context of antigen recognition 18. CD28 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) are archetypal costimulatory and co-inhibitory proteins, respectively, which interact with the shared ligands CD80 and CD86 and modulate signalling during antigen recognition, but have no known function outside of this 19. The most active area of research in recent years has been the study of co-inhibitory receptors, which also include PD-1 and 2B4 20. The role of co-stimulatory receptors is to modulate the TCR signal to increase or decrease activation of the T cell or to deviate the response of that cell down a particular differentiation pathway 21. Co-receptors are the most dedicated assistants of the TCR, being specialized for TCRs that recognize MHC class I molecules in the case of CD8, or MHC class II molecules in the case of CD4 22.

The signalling layer

A tyrosine kinase cascade, an NF-κB activating oligomeric complex and ubiquitin dependent signal termination are feature of the immunological synapse signalling layer. The TCR has no intrinsic catalytic activity and forms a multisubunit complex with CD3 in which 6 CD3 subunits (γδε2ζ2) have long cytoplasmic domains containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) {G}23. The ITAMs interact with the non-receptor tyrosine kinase ζ-associated protein of 70 kDa (ZAP70), which is crucial for TCR signalling 24. The catalytic activity of ZAP70 is essential in conventional T cells, but not regulatory T cells 24. The Src family kinase LCK is poised to phosphorylate the ITAMs and under conditions of TCR ligation can rapidly initiate ITAM phosphorylation and ZAP70 recruitment 25. The precise mechanism by which TCR ligation initiates net ITAM phosphorylation is not clear, but might simply involve the local exclusion of phosphatases, such as CD45 26. The next targets in the TCR signalling cascade are a pair of adaptor proteins, SH2-domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa (SLP76) and linker of activated T cells (LAT). Mouse genetics studies indicate that SLP76 is recruited and phosphorylated before LAT, but that LAT is essential for robust phospholipase C-γ (PLCγ) activation and increased levels of intracellular Ca2+ 27. LAT is a palmitoylated transmembrane protein with a very short extracellular domain and a long cytoplasmic domain that contains multiple phosphorylation sites; the mode of recruitment of LAT to the activated TCR is a subject of great interest, as discussed below. The transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase CD45 is crucial for LCK activation through removal of an inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation. The large extracellular domain of CD45 is thought to exclude it from the site of TCR engagement 17, 28. This might seem paradoxical, but CD45 can also inhibit TCR signalling and it is proposed that exclusion of CD45 is necessary for TCR signalling 26. Protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ) is recruited in a manner dependent on both TCR and CD28 and has a key role in the activation of a CARD domain based oligomeric complex that activates NFκB transcription factors 29, 30. Signal termination is mediated at least in part by endosomal complexes required for transport (ESCRT) proteins {G}, which orchestrate dephosphorylation of the TCR and formation of the cSMAC 31. The signalling layer is tightly integrated with the cytoskeleton to the extent that TCR signalling is f-actin dependent 28.

The cytoskeleton layer

This layer is assembled around three filament-forming proteins: actin, myosin II and, tubulin. These filaments are coordinated by the polarity network and also directly by receptor signalling 32, 33. Integrin-dependent adhesion and TCR signalling require f-actin and are partly dependent upon myosin II 28, 34. Integrins link to f-actin through proteins such as talin and vinculin 35, 36. The TCR links to actin through adaptor proteins and the actin regulator Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP), an interaction that is important for T cell activation 37. TCR engagement can induce marked actin polymerization with the generation of large, forceful protrusions 38. Microtubules are often used as a marker of secretory processes 39, but this can be misleading in some cases as transport vesicles radiating from this structure can rapidly access any part of a small T cell 40. The TCR and BCR both link to the microtubule motor dynein 41, 42. A relatively recent concept is that the TCR itself is a mechanotransducer {G}, a system for converting mechanical energy into chemical signals. Mechanotransduction in mesenchymal cells is based on the unfolding of protein domains to reveal new binding sites for signal transduction or the reinforcement of linkages to f-actin 43, 44. Experimental results differ on whether force application perpendicular or parallel to the plane of the membrane is more effective in mechanical activation of the receptor 45, 46. Genetic support for an important role of classical mechanotransduction in T cell differentiation comes from recent experiments in which proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2) deficiency results in the loss of CD8+ effector T cells 47. PYK2 is closely related to focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which is a mechanotransducer. It is not clear whether this role of PYK2, a substrate of the Src family tyrosine kinase FYN, is related to signalling down-stream of integrins or the TCR, or both. Addressing the issue of mechanotransduction at the mechanistic level will requiring working out the detailed linkages between the TCR and actin and getting to the level of single receptor measurements.

Supramolecular activation clusters

In the protypic immunological synapse, based on early images from Kupfer and colleagues8, the T cell interface is divided into supramolecular clusters: the TCR-rich central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC) {G}, the LFA1-rich peripheral supramolecular activation cluster (pSMAC) {G} and the actin- and CD45-rich distal supramolecular activation cluster (dSMAC) {G}8, 48 (Figure 1B). This pattern can be fully recapitualed by TCR antigens and adhesion ligands presented to T cells in vitro in a supported planar bilayer {G}, which indicates that the T cell actively forms the synapse pattern 10. Although this synapse pattern was originally described for helper T cells, it has since been observed for cytotoxic T cells, regulatory T cells, innate like T cells, B cells and NK cells 49-52 (BOX 2). T cell interactions with dendritic cells are more complex and result in the formation of multiple cSMAC like structures 53, 54. The application of total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) {G} in models of T cell activation by supported planar bilayers showed that TCR microclusters formed in the dSMAC and translocated through the pSMAC to the cSMAC 28, 55, 56. Observations of TCR microclusters have been confirmed by confocal microscopy with oriented cell–cell couples 57 and thus we can think of these microclusters as bona fide structures associated with T cell signalling. An important feature of these structures is that they exclude CD45 28. However, the exact nanoscale composition of microclusters is a hotly debated topic that we expand on below.

Box 2. Diversity of immunological synapses.

This review focuses on advanced research on T cell immune synapse, but the other lymphocytes NK cells and B cells are also forming synapses when they encounter respectively a target or an antigen presenting cells. Here are some points of comparison between these distinct.

Role reversal for BCR oligomer

The putative TCR dimer enhances signaling 59. In contrast, it has been proposed that BCR oligomers are auto-inhibited and that a ligand dependent switch from oligomer to monomer initiates signaling 112. The advantage of this model is that it allows a wide range of polyvalent ligands to activate B cells, whereas the T cells don't face this heterogeneity due to MHC restriction.

Batten down the receptors!

The ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) family has been implicated in regulation of the T cell synapse, but the specific mechanism has been unclear 113. Single particle tracking in B cells has shown that actin and ERM control the diffusion of BCR on the cell surface and that there is a correlation between BCR diffusion and signaling, the faster the BCR diffuse, the more they signal on steady state B cells 74.

It takes two to tango

The shape of the T cell immune synapse is affected by the type of APC with which is dances: resting B cells drive the formation of “bull eye” type synapse whereas activated B cells and DC organize a multifocal synapse 114. The cytoskeletal attachment of VCAM-1 determines the organization of the B cell synapse 115. Long and colleagues have shown that NK cells will only use ICAM-1 as a signal for killing when it is attached to the cytoskeleton 116. Both partners define the dance.

Size matters

Receptor segregation by size has been been an important organizing principle in T cell synapses 26. In NK cells, both activating and inhibitory receptor/ligand pair should have similar dimension in order to have optimal signal integration 117. Quantum dots of different size have also been utilized as atomic rulers to probe the intermembrane spacing in synapses 118. In the case of the B cell synapse such studies have not been performed in large part because the ligands for the BCR have unpredictable topology.

The prototypic synapse? One of the most ancient processes in eukaryotes is phagocytosis. Single cell organisms were ingesting each other long before organisms needing T, B and NK cells walked, crawled or swam. The formation of a phagocytic synapse may represent the ancestral prototype upon which neural and immunological synapses were modeled 119.

The receptor layer

New evidence for a dimer interface

The TCR complex is the basic building block of all the structures that are considered in this Review and recent studies have added some key information about the transmembrane and extracellular interactions that have implications for the T cell synapse 58, 59. The TCR consists of two subunits that participate in ligand recognition, either αβ or γδ. We focus our discussion on the αβ TCR that is used by most conventional helper and cytotoxic T cells, FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells, all cells that form synapses with a cSMAC as discussed above. The TCR α and β subunits each have two extracellular immunoglobulin domains, with an amino-terminal immunoglobulin variable (V) domain formed by somatic gene rearrangement, a membrane proximal immunoglobulin constant (C) domain, a transmembrane domain with conserved charged and polar residues and a short cytoplasmic domain devoid of catalytic activity or signalling motifs 60, 61. The CD3 components of the TCR complex, γ, δ and ε each have a single extracellular immunoglobulin-like domain, whereas CD3ζ has essentially no extracellular domain. All of the CD3 components have negatively charged residues in the transmembrane domain and long cytoplasmic domains containing ITAMS. The CD3ε cytoplasmic domain also contains a poly-proline motif that binds to the adaptor protein NCK. The subunit stoichiometry of the TCR complex is αβγδε2ζ2 62.

TCR dimerization has been proposed as a mechanism for the initiation of signalling. Two agonist peptide–MHC complexes or an agonist and a self-peptide-MHC complex can form the functional TCR dimer 15. Recent studies of nanoengineered, compartmentalized lipid bilayers show that 2–4 peptide–MHC ligands per TCR microcluster are required for robust Ca2+ signalling in the presence of ICAM1 63. This is consistent with a dimerization/clustering model for triggering.

Insight into the role of TCR dimers has been obtained through study of how the TCR–CD3 complex is configured. The assembly of the components of the TCR complex is in part determined by the transmembrane charges, with paired acidic domains in each of the CD3 dimers (γε, δε and ζζ) interacting with positive charges at the same depth in the transmembrane regions of the TCR α (δε and ζζ) and TCR β (γε) chains 58, 64, 65 (Figure 2). Ectodomain interactions also participate in assembly and a study using dimerization-dependent survival signals in an IL-3-dependent cell line has mapped putative extracellular dimer interfaces in the CD3 complex 59. The CD3δε heterodimer interacts with TCRα C domain and CD3γε interacts with TCRβ C domain; the two CD3ε chains (in δε and γε) also interact directly 59. These interdomain interactions allow deduction of a model in which the γε and δε heterodimers are on one side of the αβ heterodimer 59. The Wucherpfennig model for the transmembrane helices places ζζ on the other side of the αβ heterodimer 64. As ζ lacks a large extracellular domain, this leaves this face of the αβ heterodimer exposed and available for dimerization 59 (Figure 2). Mutations in this interface significantly impaired, but did not eliminate, signalling by the TCR 59. Ca2+ signalling was decreased, but could still be sustained, and the most significant effect was the loss of supramolecular TCR clustering in the cSMAC. This result is intriguing as it suggests that TCR dimerization might not be essential for initial signalling, but that dimerization contributes to formation of the cSMAC, which is a much later event.

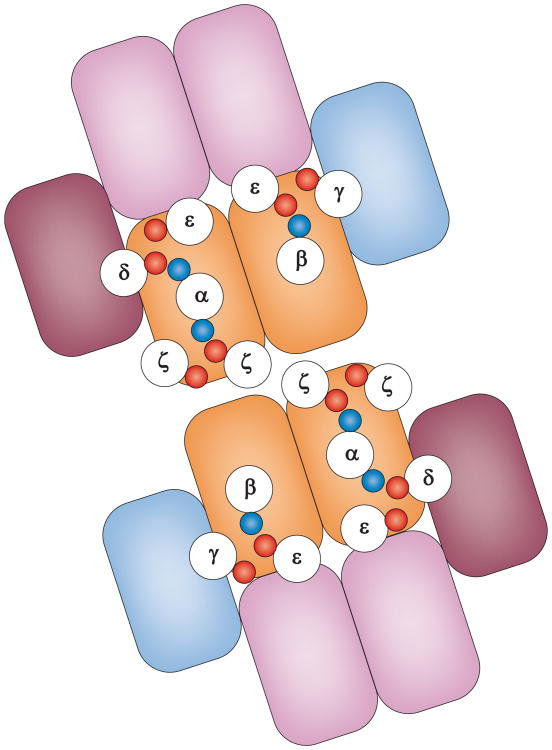

Figure 2.

Asymmetry of CD3 complexes exposes a dimerisation interface. Schematic top-down view of αβ TCR dimer proposed by Kuhns et al53. Outlined circles represent the indicated transmembrane helices based on distances taken from the ζζ dimer NMR structure62. The small blue (positive) and red (negative) circles represent the intermembrane charged residues. The boxes schematically represent the Ig-like domains of α (light blue), β (medium blue), γ (blue-green), δ (olive}. and ε (purple).

Early events following TCR interaction with ligands

The interaction of the TCR with peptide–MHC complexes has been studied in detail through structural and biophysical methods, but it has been difficult to correlate the interaction properties measured in solution with the large dynamic range of T cell functions that can be triggered by these interactions 16, 66. The earliest events in TCR interaction at the T cell surface are probably a product of initial TCR organization, signalling and cytoskeletal feedback such that in situ measurements in an interface are essential. A creative way to probe these events has created excitement in the field because it provides kinetic measurements that are predictive of biological outcomes 2. These measurements are based on the micromanipulation of T cells and peptide–MHC-bearing red blood cells (RBCs) into repeated contact and withdrawal to test for the formation of single bonds. The resulting data, which include the density of TCR and peptide–MHC complexes, the contact area, the contact duration and the probability of bond formation, undergo statistical analysis with a standard adhesion model to generate 2D kinetic rates. This is a method for detecting single receptor-ligand interactions and thus examines the earliest sub-second events. Surprisingly, in this model, agonist strength was predicted by a faster 2D on rate and this parameter showed a large dynamic range. This contrasts with previous measurements taken in solution where the dynamic range of on rates is smaller and many systems are dominated by differences in the off-rate. Inhibition of f-actin and disruption of membrane structure through cholesterol extraction in the T cell decreased the off-rate and dramatically decreased the on-rate. Thus, an integrated process involving crosstalk between the signalling and cytosketelal layers and the receptor layer is responsible for amplifying a relatively small difference in interaction energy between TCR and peptide–MHC to generate a large range of 2D interaction rates and hence a large range of functions. Single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) {G} measurements in the supported planar bilayers system revealed that f-actin-dependent effects increase the off-rate of the TCR–peptide–MHC interaction by ∼10-fold 3. This study is a beautiful example of how structure can link to biophysical measurements to gain unique biological insights. In order to explain the biology of TCR discrimination, we need to understand the mechanisms that control the rate of early bond formation between TCR and peptide–MHC. A good place to start is an understanding of TCR distribution on the T cell surface and how this relates to signalling events.

Signalling TCR microclusters can also incorporate co-stimulatory receptors such as CD28 67. CD28 can function both to enhance signalling, for example by recruiting PKC-θ 67, and to promote TCR recognition of weak ligands 31, 68. In fact, some weak ligands are not recognized at all by T cells without CD28 ligation, but are then seen as strong agonists in the presence of CD28 ligands 31. The role of CD28 in promoting the recognition of weak agonists might be a point of vulnerability for adaptive immunity. For such ligands, the induction of peripheral tolerance would require expression of the CD28 ligands CD80 and/or CD86 to inactivate or delete autoreactive T cells; expression of these ligands is low in the steady state. Inflammatory processes that increase the expression of CD80 or CD86 could then allow recognition of and response to these autoantigens, potentially leading to disease if the autoimmune inflammation becomes self-sustaining. These effects begin with enhancing the function or formation of TCR microclusters. CD28 incorporation into TCR microclusters enhances the recruitment of PKC-θ and increases NF-κB activation 67. The co-inhibitory receptor CTLA4 directly competes with CD28 in TCR microclusters for binding to CD80 and suppresses CD28-mediated PKC-θ recruitment 69. CTLA4 might also have agonistic activity to increase motility 70. This theme of adding or substracting function from TCR microclusters through ligand dependent inclusion of additional receptors will likely be of broad importance in the regulation of immune responses.

The signalling layer

Two views of LAT and TCR clusters

One of the most interesting current issues in T cell signalling is how TCR and LAT come together. Mark Davis and colleagues have used membrane sheet electron microscopy (EM) {G}, photoactivation localization microscopy (PALM){G} and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS){G} to make the argument that TCR and LAT are initially segregated in sub-micron “protein islands” in a protein-poor “lipid sea” on the plasma membrane 4. During signalling, the protein islands seem to tile together without mixing. It is proposed that visible microclusters are based on these conjoined islands (Figure 3A, C). This is an intriguing model and has implications for membrane structure that are far reaching. For example, the model suggests that much of the membrane is normally composed only of lipids and that the precursors of signalling microclusters can be well insulated from each other in the steady state and then rapidly form signalling complexes when this insulation breaks down to allow lateral interactions between protein islands. The observation that islands don't mix freely also suggests that the islands might be rapidly segregated again to terminate signalling. There are many possibilities for combinatorial control and many questions about how interactions are regulated by receptor engagement. However, a totally different view of this process has emerged from dynamic studies of LAT in T cells undergoing signalling in Dan Davis's lab and a detailed analysis in fixed cells by super-resolution fluorescence microscopy methods by Gaus and colleagues 5, 6. These studies conclude that the active pool of LAT is localized to sub-synaptic vesicles (SSVs) {G} that dock with engaged TCR clusters such that the kinases associated with TCR ITAMs at the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane phosphorylate LAT associated with SSV's (Figure 3B, D). The proposal that LAT is recruited from SSVs in trans, without membrane fusion, is as novel in the signalling world as the idea of protein islands is to membrane structure.

Figure 3.

Two views of TCR and LAT clusters. A and C. Dynamic protein ‘islands‘. TCR complexes in red and LAT molecules in green are organized in concatemers within protein islands in the steady state. After peptide–MHC complex recognition (not represented) the concatemers fuse to form a signalling microcluster. The cortical actin cytoskeleton is essential for this process. B and D. Subsynaptic vesicles. TCR complexes in red are organized in protein island concatemers, as well as some LAT proteins in the steady state. LAT can also be found anchored to sub-synaptic vesicles. After TCR triggering, only the LAT protein anchored to vesicles participates in signal transduction. The vesicles are proposed to be so close to the cell membrane that tagged LAT has been visualized as a membrane protein in some studies.

TCR islands

The TCR has recently become a model system for the consideration of larger scale organization of biological membranes. The lipid components of biological membranes exist in two phases: liquid disordered and liquid ordered. As liquid ordered domains strongly exclude most transmembrane polypeptides 71, most transmembrane proteins exist in disordered lipid domains. Within these domains, we discuss two major forces that are thought to affect the heterogeneity of biological membranes: cytoskeletal corrals and thermodynamic effects of the protein-lipid interface. Cytoskeletal corrals {G} have long been proposed as a mechanism for limiting the diffusion of membrane proteins, the most detailed explanation being provided by Kusumi's picket fence model 72. This model holds that cortical filament {G} systems interact with cytoplasmic domains of membrane proteins to restrict diffusion in the lipid bilayer. Escape from corrals involves “hop” diffusion, a process in which a membrane protein stochastically evades barriers and moves from one corral to another. In this model, there is rapid diffusion of proteins within corrals and slower movement between corrals, which leads to spatial clustering. Both Fc receptors and B cell receptors can be excluded from areas of the membrane by f-actin bundles, providing one potential explanation for the relatively protein-poor lipid sea separating protein islands 73, 74. The dynamic nature of the corrals and the independent diffusion of proteins within corrals allow for the appearance of protein clusters in a snap-shot view, without the observation of correlated diffusion in dynamic measurements such as FCS or single particle tracking 73, 75. Although actin bundles might exclude all transmembrane proteins with cytoplasmic domains, a more selective mechanism to generate protein islands of different compositions and a protein-poor “sea” is based on disturbance of the lipid bilayer structure by transmembrane elements of proteins 76. These effects depend on the size, shape and polarity of the transmembrane segments and can propagate through the membrane for tens of nanometers. This mechanism can generate nanoscale protein clusters of different composition with a protein-depleted sea between them, while retaining a high degree of dynamics. Testing these models will require innovative biophysical methods. There is biological and biochemical evidence to support the idea that the TCR can be pre-clustered on the cell surface, particularly in previously activated T cells 77-79. Being able to deconstruct membranes with detergents and analyze protein domains is an attractive possibility, but most of these methods convey little information about the heterogeneity of the particles that are isolated and thus underestimate the complexity of the system. Single particle biochemical approaches should be useful in the further analysis of TCR islands and nanoclusters at a biochemical level 80. These methods can interrogate many other properties of the particles observed, including lipid content, and allow for direct analysis of heterogeneity in populations of particles. Thus, there is an emerging theoretical framework and tool kit for understanding the segregation of multiple plasma membrane proteins into islands or nanodomains that can interact with more ordered lipid domains.

LAT islands

Ordered membrane domains, referred to as lipid rafts {G}, might account for the segregation of LAT into discrete protein islands 81. Liquid ordered domains in biological membranes are typically rich in sphingolipids with saturated acyl chains and cholesterol. Lipid rafts have attracted significant attention as a mechanism for the sorting of glycolipid anchored and palmitoylated proteins, as the lipid component of these proteins is compatible with the more ordered membrane domains 82. Biophysical and electron microscopy methods indicate that lipid rafts of glycolipid-anchored proteins are less than 70 nm in size 83, 84. The TCR+ and LAT+ protein islands are segregated in the basal state and FCS measurements show that the movement of TCR and LAT molecules is not correlated. During activation, TCRs become variably associated with lipid rafts 85, TCR+ and LAT+ protein islands are observed to form concatemers 4 and TCR and LAT dynamics in the membrane of intact cells become highly correlated 4. So, according to the protein island model, there are three crucial membrane compartments in T cells: TCR+ protein islands (in the disordered lipid domains), LAT+ protein islands (in the ordered lipid rafts) and a sea of TCR- and LAT-free membrane that seems to insulate these islands in the steady state.

SSVs

In contrast to the protein island model, there are two studies that argue for an important role of LAT in SSVs. The first paper from the Davis lab builds on work from the Bunnell and Samelson labs 86 using the model of T cell activation based on Jurkat T cells; in this study, they tracked LAT+ SSVs in addition to previously described static TCR–ZAP70 clusters (that are anchored by substrate-immobilized CD3-specific antibody) and centripetally moving SLP76 clusters 5. The LAT+ SSVs were observed to move rapidly and apparently randomly and visit both TCR–ZAP70 and SLP76 clusters. Colocalization of LAT+ SSVs with TCR–ZAP70 clusters correlated with LAT phosphorylation. The Gaus group used PALM and Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) {G} to support the model that some of the steady-state LAT clusters are actually in SSVs and that a subset of LAT+ SSVs more closely interact with the plasma membrane and are phosphorylated by kinases associated with triggered TCRs 6. The docking of abundant LAT+ SSVs to TCR clusters is an attractive idea because it provides a potentially large degree of interaction between TCR-associated kinases and the extended LAT cytoplasmic domain. LAT+ SSVs docked to the TCR even when the tyrosines in LAT were mutated to phenylalanines; the implications of this observation are that the docking/adhesion process is independent of LAT being able to recruit additional signalling components. One could also speculate that changes in the conformation of TCR ITAMs might have an important role in LAT+ SSV docking. The cytoplasmic ITAMs of the TCR lack a specific structure in solution, but their interaction with acidic phospholipids in the lipid bilayer results in a discrete inactive conformation in which the ITAM tyrosines are buried in the membrane prior to TCR ligation 87, 88. This configuration might be similar to the “closed” conformation of the BCR detected by FRET 89. The movement of LAT+ SSVs is consistent with a mixture of different transport modes, including confined diffusion, actin rocket formation and microtubule motors.

The SSV docking model for bringing LAT to TCR microclusters has implications for the compartmentalization of signalling. Phosphorylated LAT recruits PLC-γ, which is crucial for the production of diacylglycerol (DAG) from PIP2 for activation of RAS-GRP and PKC-θ 90, 91. If the activated PLC-γ targets PIP2 in the SSV, then the initial activation of RAS and PKC-θ would take place on the SSV, or a compartment to which the DAG can be delivered by fusion of the SSV prior to phosphorylation by DAG kinases 92. The possibility that PLC-γ could make DAG on SSVs might explain why TCR- and LFA-1-dependent DAG production at the plasma membrane has been shown to take place through activation of phospholipase D2 and phosphatidic acid phosphatase, rather than through PLC-γ 93. However, many conclusions about the localization of signalling intermediates have been based on imaging methods that might not resolve SSVs from plasma membranes. Signalling by receptors in endosomes, such as the pre-TCR or some Toll-like receptors, is a well-described process 94. The participation of SSVs in T cell signalling based on a docking mechanism is a novel situation and creates many new possibilities for the compartmentalization of signalling that need to be explored.

It is possible that some of the heterogeneity in TCR distribution (ie formation of microclusters) on resting cells might be due either to the dynamics of protein islands or the transience of SSVs. TIRFM of T cells spread on an ICAM1+ bilayer showed a heterogeneous distribution of TCRs with definable spots with an average of ∼8 receptors 28. The lowest concentration of peptide–MHC that induces robust T cell signalling generates microclusters containing ∼11 TCRs on average. Thus, signalling TCR microclusters are weakly distinguished from steady-state TCR clusters by size. The signalling microclusters are also more persistent than steady-state clusters in that they can be tracked for up to 2 minutes, and the signalling microclusters excluded the tyrosine phosphatase CD45 28. Steady-state clusters formed on bilayers with ICAM1 alone did not persist for more than ∼6 seconds and did not exclude CD45. CD45 exclusion provides a mechanism for the local enhancement of TCR signalling (by preventing the dephosphorylation of signalling components) and so is probably a functional marker for a signalling microcluster. However, the labeling methods used in these studies would not be able to distinguish between TCRs in the plasma membrane and TCRs in SSVs, so the possibility that some TCR clusters observed in the steady state are actually SSVs needs to be investigated. Experiments with membrane dyes seemed to reject the notion that any TCR microclusters were associated with discrete vesicles, but the sub-synaptic cytoplasm might contain so many SSVs that the fluorescent signals merge into a continuum. Methods such as interferometric super-resolution fluorescence microscopy {G} should enable a more precise mapping of SSVs and their composition 95.

The experimental evidence in favour of protein-island and SSV models is currently about equal. In each case there have been provocative observations, but lack of a detailed mechanism to explain how access of the TCR to LAT is regulated at a molecular level. It is likely that even more innovative approaches will be needed to determine if one of these models is correct or if the reality is a mix of both or some yet to be proposed alternative view.

The cytoskeletal layer

Microcluster translocation

The earliest studies linking TCR microclusters to signalling were carried out with substrate-bound CD3-specific antibody, the Jurkat T cell line transfected with fluorescent protein-tagged signal transduction proteins and confocal microscopy 96-98. In these studies, large TCR clusters were generated during T cell spreading on the substrate, and these clusters recruited ZAP70, SLP76, NCK and WASP. An expanding f-actin ring drives this spreading process. ZAP70–GFP remained with the TCR microclusters as expected, but surprisingly, SLP76–GFP signalling structures were shed from the TCR microclusters and moved centripetally 97. Signalling is stronger when the shedding of these clusters is prevented, suggesting that the process is involved in signal termination. The movement of these structures depends upon centripetal f-actin flow and can be prevented by incorporating VCAM1, a ligand for the integrin VLA4, into the substrate with the CD3-specific antibody, which increases T cell activation 86. There are several questions regarding how the protein island or SSV models could account for these observations. Are integrins present in a particular protein island? How would such an island interface with the TCR+ and LAT+ protein islands? Given that SSVs don't move centripetally, how do they avoid this and do they have a specific mechanism to home to active TCR clusters?

Model for control of on-rate by glycocalyx and f-actin

As mentioned above, the on-rate seems to be the key 2D kinetic parameter that is controlled by the TCR–peptide–MHC interaction. The key to a high TCR affinity in 2D is to set the intermembrane distance between the T cell and APC such that the binding sites of receptor and ligand are positioned to interact whenever they diffuse together laterally 99, 100. This intermembrane distance would be ∼15 nm for the extended TCR and peptide–MHC complex 17, 26. To bring the T cell and APC membranes within 15 nm, the T cell needs to overcome repulsion of the glycocalyx {G} that surrounds each cell. The LFA1–ICAM1 interaction holds the T cell and APC membranes ∼40 nm apart, but this might create a starting point for actin polymerization to push on the membrane regions around the LFA1 clusters to generate transient areas of 15 nm spacing (Figure 4). It is reasonable to speculate that the evolutionary choice of 15 nm being the optimal intermembrane spacing for many immunoreceptors represents a natural balancing point between the pushing force that can be induced by actin polymerization and the repulsive force generated by the gycocalyx of T cells and APCs. If this were the case, no sophisticated feedback system would be needed to generate 15 nm spacing. Once a TCR engages a single agonist peptide–MHC ligand, initial signals may stabilize the actin pushing force, perhaps by creating additional binding sites for f-actin, and lead to a sustained 15 nm contact area that can exclude CD45 2. This feedback would be faster than the earliest signalling events measured by visualization of clustering and Ca2+ mobilization 101, on a sub-second time scale.

Figure 4.

Model for how f-actin can promote a fast on-rate. Actin polymerization applies the force needed to bring TCRs to the correct distance from APCs for peptide–MHC recognition (∼15 nm). A. Integrin mediated adhesion anchors the membranes at 40 nm and allows actin-based protrusions that complex the glycocalyx to ∼15 nm spacing to sample the APC surface for peptide–MHC complexes. We propose that the most robust system for achieving 15 nm spacing is based on a repulsive force from the glycocalyx (not shown) countered by a protrusive force from actin polymerization (arrow) that is balanced when the membranes are 15 nm apart. Receptor–ligand pairs such as the TCR and peptide–MHC have co-evolved with actin and the glycan-modifying enzymes to take advantage of this point of balance. Sub-second feed-forward effects of initial TCR–peptide–MHC interactions stabilize the microcluster. The stabilized microcluster connects to centripetal actin flow to move the cluster laterally within the immunological synapse. The model is schematized using the protein island model of lateral TCR and LAT for simplicity. LAT recruitment would not be required for the feed forward signal as this takes place in seconds, rather than on a sub-second time frame.

Mechanotransduction

One of the most interesting spinoffs of the T cell synapse is the idea that the TCR is a mechanotransducer 45. The periphery of the T cell synapse, in which many TCR microclusters are formed, undergoes cycles of f-actin-based protrusion and myosin II-dependent retraction that indicate that engaged TCRs are immediately subjected to significant mechanical forces 102. The role of myosin II in TCR signalling and migration is controversial and the forces generated by actin polymerization alone might be sufficient for TCR activation in some contexts 34, 103, 104. The movement of TCR microclusters driven by actin- and microtubule-based motors 41, 56 has been suggested to accelerate the off-rate of the TCR–peptide–MHC interaction 3. Two groups have shown that non-signalling TCR complexes can be activated by the application of lateral or normal forces to preformed, but not functional, receptor clusters 45, 46. In this context, it is exciting that PYK2, a bona fide force-transducing kinase, controls the effector differentiation of CD8+ T cells 47.

cSMAC- the end or a beginning?

The cSMAC sits at the end of the centripetal actin conveyor belt that moves TCRs, as captured by the dramatic movies of synaptic actin dynamics 56. The cSMAC has two components when CD28 is engaged: a CD28-rich, TCR-poor region with active signalling, and a TCR-rich, CD28-negative region 54, 105. The CD28-rich component seems to behave much like a TCR microcluster and we will not discuss it further here. Signals are terminated in the TCR-rich central region and this process is dependent upon CD2AP, an adaptor protein that recruits E3 ubiquitin ligases 106. More fundamentally, the TCR-rich component of the cSMAC requires the ESCRT component TSG101 for both signal termination and central transport 31. ESCRTs can viewed as a new type of cortical cytoskeleton that mediate membrane scission through formation of spiral polymers 107. TSG101 is involved in both HIV budding from the plasma membrane and the generation of multivesicular bodies, which release exosomes when they fuse to the plasma membrane. Exosomes are a specific example of extracellular microvesicles, which can be generated by several mechanisms including budding from the plasma membrane. Recently, it has been shown that Jurkat T cells secrete ESCRT dependent exosomes that are taken up by superantigen-presenting Raji B cells 7. This is mechanistically distinct from other transfer processes, such as trans-endocytosis 108, which involved transfer of membrane patches in the opposite direction (from APC to T cell). Remarkably, the Raji cells incorporate microRNAs from the exosomes and alter their gene expression 7. This mode of communication by “exosomal shuttle RNA” was first revealed in mast cells 109. The exosomes that are formed through sorting of TCRs into multivescicular bodies by ESCRT components will have TCRs on their surface and would have the capacity to target any cell expressing the appropriate peptide–MHC complex. This phenomenon of microvesicles targeted by surface TCRs had been observed earlier in cytotoxic T cells 110. Theses structures, which were proposed to deliver a kiss of death, might instead execute a much more delicate reprogramming of recipient cells through RNA shuttling. Whether T cell exosomes are delivered directly through the T cell synapse or more generally as paracrine signals remains to be determined; both methods seem possible based on past experience with directional versus non-directional secretion from T cells 40. We conclude that the cSMAC can end TCR signalling, but that some of the TCRs reemerge associated with microvesicles that tune gene expression in APCs.

In conclusion, the cytoskeletal layer plays a key role at all stages of TCR engagement and signalling, but there is still much to learn about the detailed mechanisms. While the picture looks hopelessly complex at some levels, some elegant principles must contribute to the robustness of the system.

Summary

The natural history of the TCR during activation of a T cell is only beginning to be mapped. We have organized our view of the T cell synapse into three highly interactive layers in order to focus in on issues related to interactions with peptide–MHC ligands, signalling and transport to the cSMAC. The past year has seen the application of several innovative, state of the art methods to each of these issues (BOX 1). The data from these efforts are clear to see, but the interpretation of these data is still at a stage where creative interpretations can be transformative. The interaction between TCRs and peptide–MHC complexes will best be understood by collecting kinetic data in membrane interfaces. Location is everything and we suggest that this recognition system has evolved to use both membrane and actin dynamics as an amplifier to get big differences in biology from small differences in chemical kinetics. One of the key events in T cell signalling is bringing together the triggered TCR and LAT. The field is now faced with two revolutionary ideas: protein islands that come together in the plasma membrane and SSVs that dock to TCR clusters at the plasma membrane to complete a signalling complex as an intracellular adhesion event. Further testing these models will rely on innovation at the interface between 3D super-resolution and high-speed imaging. The formation of TCR dimers and ESCRT components enable the formation of the cSMAC. The cSMAC ends TCR signalling in the conventional sense, but seems to create a TCR+ nano-particle that can carry RNAs to cells expressing the cognate antigen. It remains to be seen if this is truly a synaptic transfer or if the structures are distributed to all local APCs. Advances in the past year have changed our view on many issues related to T cell signalling and the immunological synapse. The pace of discovery is increasing as more groups are applying sophisticated imaging and modelling approaches to immunological synapses.

On-line summary.

Single molecule methods are leading to advances in understanding immune cell activation, but different interpretation of the cutting edge data can also trigger controversies.

Probing single T cell receptor (TCR)-MHC-peptide bonds at early times has led to the discovery that control of the 2D on-rate is a critical parameter that amplifies apparently small chemical differences.

Measuring single TCR-MHC-peptide interactions using fluorescence resonance energy transfer reveals that cytoskeletal force increase the off-rate by ∼10-fold, further emphasizing the importance of efficient MHC-peptide capture.

Electron microscopy and super-resolution fluorescence microscopy reveals that TCR and the adapter LAT are organized into protein islands in a protein poor lipid sea and that collisions of TCR and LAT islands initiate signalling.

Time-lapse and super-resolution fluorescence microscopy suggest that TCR clusters in the plasma membrane interact in trans with LAT in sub-synaptic vesicles to initiate signalling.

Mutations in a putative TCR dimer interface impair cSMAC formation, a TSG101 dependent process that may transfer nucleic acid messages from T cells to antigen presenting cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Varma, K. Choudhuri, S. Kumari and N. Destainville for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI043549, P01 AI045757 and PN2 EY016586.

Glossary

- Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)

The ITAM is an amino acid sequence (YxxI/Lx6-12YxxI/L) found in a large number of receptors or adaptor proteins. After phosphorylation, ITAMs function as docking sites for proteins containing tandem SH2 domains, such as ZAP70.

- Endosomal complexes required for transport (ESCRT) proteins

The ESCRT proteins coordinate the degradation of ubiquitylated substrates via multivesicular bodies. There are four ESCRT complexes (0, I, II, and III) with unique roles in signal termination and receptor degradation.

- Mechanotransducer

A protein able to convert mechanical force into a biochemical signal.

- Central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC).

During T-cell activation, TCRs accumulate into a central cluster (known as the cSMAC) at the interface between the T cell and the APC. The cSMAC is surrounded by a leukocyte-function-associated antigen-1 (LFA1)-integrin ring (known as the pSMAC) in a bulls-eye fashion, and this characteristic receptor organization (cSMAC surrounded by the pSMAC) constitutes the mature immunological synapse. The large proteins are excluded from the mature immunological synapse and form the dSMAC.

- Sub-synaptic vesicles

Refers to endosomal membranes and other structures within 200 nm of the plasma membrane in the immunological synapse.

- Cytoskeletal corrals

Proteins associated with the membrane cytoskeleton can form “corrals” that limit the diffusion of proteins within the plasma membrane.

- Cortical filament

Actin and cytskeleton proteins present in close proximity to the cell membrane influence the membrane geometry and the behaviours of proteins composing this membrane.

- Lipid rafts

Lipid domains enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids and phospholipids with saturated acyl chains. The lipid phase is referred to as liquid ordered, in contrast to the liquid disordered domains that characterize the bulk of biological membranes. Lipid rafts are small (∼70 nm) and dynamic.

- Glycocalyx

An extracellular polymer composed of glycoprotein that covers the outside of eukaryotic cells.

- Polarity network

Evolutionarily conserved cytoplasmic proteins defined by genetic screens for gene products required for cell polarity (e.g. apical vs. basal, front vs. back) dependent processes.

Biographies

Michael L. Dustin earned his PhD from Harvard University where he studied biochemistry and regulation of adhesion molecules in the lab of Timothy A. Springer, Ph.D. As a post-doc with Stuart Kornfeld at Washington University he used chimeric protein libraries to define motifs that identify lysosomal enzymes. Early in his independent career at Washington University he led a collaborative team in visualizing formation of the immunological synapse using the supported planar bilayer model. He is currently a Professor at NYU School of Medicine, where is lab focuses on cell biology of T cell activation using advanced imaging methods.

David Depoil earned his Ph.D in 2006 from the University of Toulouse, where he studied the formation of the immunological synapse when T cells encounter several antigen-presenting cells. He carried out a first postdoctoral training at the Cancer Research UK institute, where he studied the implication of the molecule CD19 during B cell activation and its essential role for the formation of BCR microclusters. He is currently post-doctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Dustin. His research focuses on understanding how MHC-peptide affinity influences TCR microcluster formation and how accessory molecules fine-tune this process.

References

- 1.Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2*.Huang J, Zarnitsyna VI, Liu B, Edwards LJ, Jiang N, et al. The kinetics of two-dimensional TCR and pMHC interactions determine T-cell responsiveness. Nature. 2010;464:932–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08944. This paper utilized micromanipulation of T cells and MHC-peptide coated erythrocyte probes to determine 2D kinetic rates for formation of the initial TCR-MHC-peptide interactions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Huppa JB, Axmann M, Mortelmaier MA, Lillemeier BF, Newell EW, et al. TCR-peptide-MHC interactions in situ show accelerated kinetics and increased affinity. Nature. 2010;463:963–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08746. This paper utilized single molecule FRET to determine that active mechanism increase the off-rate for the TCR-MHC-peptide interaction in an immunological synapse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4*.Lillemeier BF, Mortelmaier MA, Forstner MB, Huppa JB, Groves JT, et al. TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:90–6. doi: 10.1038/ni.1832. This paper utilized electron microscopy, PALM and FCS measurements to support a model of TCR and LAT proteins islands. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Purbhoo MA, Liu H, Oddos S, Owen DM, Neil MA, et al. Dynamics of subsynaptic vesicles and surface microclusters at the immunological synapse. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000645. This study utilized confocal microscopy to support a model in which LAT containing vesicles doc with TCR signaling compelxes to form signaling complexes required for early TCR signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Williamson DJ, Owen DM, Rossy J, Magenau A, Wehrmann M, et al. Pre-existing clusters of the adaptor Lat do not participate in early T cell signaling events. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:655–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.2049. This study utilized PALM to determine the location of LAT in T cells responding that antigen receptor stimulation and novel data analysis to differentiate plasma membrane vs vesiculare populations, support a role for vesicular LAT in signaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Mittelbrunn M, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, Gonzalez S, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun. 2011;2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. This study demonstrates that T cell derives exosomes contains miRNAs that modulate B cell gene expression on transfer. Support was provided for exosome transfer via the immunological synapse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–6. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dustin ML, Olszowy MW, Holdorf AD, Li J, Bromley S, et al. A novel adapter protein orchestrates receptor patterning and cytoskeletal polarity in T cell contacts. Cell. 1998;94:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, et al. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fooksman DR, Vardhana S, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Liese J, Blair DA, et al. Functional anatomy of T cell activation and synapse formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dustin ML, Long EO. Cytotoxic immunological synapses. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dustin ML. Hunter to gatherer and back: immunological synapses and kinapses as variations on the theme of amoeboid locomotion. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:577–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanchanawong P, Shtengel G, Pasapera AM, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, et al. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature. 2010;468:580–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krogsgaard M, Li QJ, Sumen C, Huppa JB, Huse M, et al. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature. 2005;434:238–43. doi: 10.1038/nature03391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels MA, Teixeiro E, Gill J, Hausmann B, Roubaty D, et al. Thymic selection threshold defined by compartmentalization of Ras/MAPK signalling. Nature. 2006;444:724–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–34. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diehn M, Alizadeh AA, Rando OJ, Liu CL, Stankunas K, et al. Genomic expression programs and the integration of the CD28 costimulatory signal in T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092284399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, et al. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:116–26. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artyomov MN, Lis M, Devadas S, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK. CD4 and CD8 binding to MHC molecules primarily acts to enhance Lck delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16916–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010568107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reth M. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature. 1989;338:383–4. doi: 10.1038/338383b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deindl S, Kadlecek TA, Cao X, Kuriyan J, Weiss A. Stability of an autoinhibitory interface in the structure of the tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 impacts T cell receptor response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911512106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nika K, Soldani C, Salek M, Paster W, Gray A, et al. Constitutively active Lck kinase in T cells drives antigen receptor signal transduction. Immunity. 2010;32:766–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choudhuri K, Wiseman D, Brown MH, Gould K, van der Merwe PA. T-cell receptor triggering is critically dependent on the dimensions of its peptide-MHC ligand. Nature. 2005;436:578–82. doi: 10.1038/nature03843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mingueneau M, Roncagalli R, Gregoire C, Kissenpfennig A, Miazek A, et al. Loss of the LAT adaptor converts antigen-responsive T cells into pathogenic effectors that function independently of the T cell receptor. Immunity. 2009;31:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2006;25:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, Lo PF, Zal T, Gascoigne NR, Smith BA, et al. CD28 plays a critical role in the segregation of PKC theta within the immunologic synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9369–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142298399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thome M, Charton JE, Pelzer C, Hailfinger S. Antigen receptor signaling to NF-kappaB via CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003004. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Vardhana S, Choudhuri K, Varma R, Dustin ML. Essential role of ubiquitin and TSG101 protein in formation and function of the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2010;32:531–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.005. Demonstrates the role of TSG101 in signal termination in TCR microclusters and cSMAC formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krummel MF, Macara I. Maintenance and modulation of T cell polarity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1143–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkhardt JK, Carrizosa E, Shaffer MH. The actin cytoskeleton in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:233–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilani T, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Vardhana S, Bretscher A, Dustin ML. T cell antigen receptor signaling and immunological synapse stability require myosin IIA. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:531–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith A, Carrasco YR, Stanley P, Kieffer N, Batista FD, et al. A talin-dependent LFA-1 focal zone is formed by rapidly migrating T lymphocytes. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:141–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolz JC, Medeiros RB, Mitchell JS, Zhu P, Freedman BD, et al. WAVE2 regulates high-affinity integrin binding by recruiting vinculin and talin to the immunological synapse. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5986–6000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00136-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannon JL, Burkhardt JK. Differential roles for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in immune synapse formation and IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2004;173:1658–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husson J, Chemin K, Bohineust A, Hivroz C, Henry N. Force generation upon T cell receptor engagement. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stinchcombe JC, Majorovits E, Bossi G, Fuller S, Griffiths GM. Centrosome polarization delivers secretory granules to the immunological synapse. Nature. 2006;443:462–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huse M, Lillemeier BF, Kuhns MS, Chen DS, Davis MM. T cells use two directionally distinct pathways for cytokine secretion. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:247–55. doi: 10.1038/ni1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto-Tane A, Yokosuka T, Sakata-Sogawa K, Sakuma M, Ishihara C, et al. Dynein-driven transport of T cell receptor microclusters regulates immune synapse formation and T cell activation. Immunity. 2011;34:919–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnyder T, Castello A, Feest C, Harwood NE, Oellerich T, et al. B cell receptor-mediated antigen gathering requires ubiquitin ligase cbl and adaptors grb2 and dok-3 to recruit Dynein to the signaling microcluster. Immunity. 2011;34:905–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawada Y, Tamada M, Dubin-Thaler BJ, Cherniavskaya O, Sakai R, et al. Force sensing by mechanical extension of the Src family kinase substrate p130Cas. Cell. 2006;127:1015–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.del Rio A, Perez-Jimenez R, Liu R, Roca-Cusachs P, Fernandez JM, et al. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323:638–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim ST, Takeuchi K, Sun ZY, Touma M, Castro CE, et al. The alphabeta T cell receptor is an anisotropic mechanosensor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31028–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li YC, Chen BM, Wu PC, Cheng TL, Kao LS, et al. Cutting Edge: mechanical forces acting on T cells immobilized via the TCR complex can trigger TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:5959–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beinke S, Phee H, Clingan JM, Schlessinger J, Matloubian M, et al. Proline-rich tyrosine kinase-2 is critical for CD8 T-cell short-lived effector fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16234–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011556107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Maslanik W, Delli J, Kappler J, et al. Staging and resetting T cell activation in SMACs. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:911–7. doi: 10.1038/ni836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anikeeva N, Somersalo K, Sims TN, Thomas VK, Dustin ML, et al. Distinct role of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 in mediating effective cytolytic activity by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502467102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zanin-Zhorov A, Ding Y, Kumari S, Attur M, Hippen KL, et al. Protein kinase C-theta mediates negative feedback on regulatory T cell function. Science. 2010;328:372–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1186068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCarthy C, Shepherd D, Fleire S, Stronge VS, Koch M, et al. The length of lipids bound to human CD1d molecules modulates the affinity of NKT cell TCR and the threshold of NKT cell activation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1131–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu D, Bryceson YT, Meckel T, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Dustin ML, et al. Integrin-dependent organization and bidirectional vesicular traffic at cytotoxic immune synapses. Immunity. 2009;31:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brossard C, Feuillet V, Schmitt A, Randriamampita C, Romao M, et al. Multifocal structure of the T cell - dendritic cell synapse. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1741–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tseng SY, Waite JC, Liu M, Vardhana S, Dustin ML. T cell-dendritic cell immunological synapses contain TCR-dependent CD28-CD80 clusters that recruit protein kinase Ctheta. J Immunol. 2008;181:4852–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokosuka T, Sakata-Sogawa K, Kobayashi W, Hiroshima M, Hashimoto-Tane A, et al. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaizuka Y, Douglass AD, Varma R, Dustin ML, Vale RD. Mechanisms for segregating T cell receptor and adhesion molecules during immunological synapse formation in Jurkat T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biggs MJ, Milone MC, Santos LC, Gondarenko A, Wind SJ. High-resolution imaging of the immunological synapse and T-cell receptor microclustering through microfabricated substrates. J R Soc Interface. 2011 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Call ME, Wucherpfennig KW, Chou JJ. The structural basis for intramembrane assembly of an activating immunoreceptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1023–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59*.Kuhns MS, Girvin AT, Klein LO, Chen R, Jensen KD, et al. Evidence for a functional sidedness to the alphabetaTCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5094–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000925107. This study utilizes a screening method for dimerization to map dimer interfaces in the TCR-CD3 complex and define a putative dimerization interface in the TCR with a role in TCR centralization in the immunological synapse. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jorgensen JL, Reay PA, Ehrich EW, Davis MM. Molecular components of T-cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:835–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.004155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhns MS, Davis MM, Garcia KC. Deconstructing the form and function of the TCR/CD3 complex. Immunity. 2006;24:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Call ME, Pyrdol J, Wucherpfennig KW. Stoichiometry of the T-cell receptor-CD3 complex and key intermediates assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum. Embo Journal. 2004;23:2348–2357. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manz BN, Jackson BL, Petit RS, Dustin ML, Groves J. T-cell triggering thresholds are modulated by the number of antigen within individual T-cell receptor clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018771108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Call ME, Pyrdol J, Wiedmann M, Wucherpfennig KW. The organizing principle in the formation of the T cell receptor-CD3 complex. Cell. 2002;111:967–79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01194-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Call ME, Schnell JR, Xu C, Lutz RA, Chou JJ, et al. The structure of the zetazeta transmembrane dimer reveals features essential for its assembly with the T cell receptor. Cell. 2006;127:355–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qi S, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK. Molecular flexibility can influence the stimulatory ability of receptor-ligand interactions at cell-cell junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4416–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510991103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokosuka T, Kobayashi W, Sakata-Sogawa K, Takamatsu M, Hashimoto-Tane A, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of T cell costimulation by TCR-CD28 microclusters and protein kinase C theta translocation. Immunity. 2008;29:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaw AS, Dustin ML. Making the T cell receptor go the distance: a topological view of T cell activation. Immunity. 1997;6:361–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yokosuka T, Kobayashi W, Takamatsu M, Sakata-Sogawa K, Zeng H, et al. Spatiotemporal basis of CTLA-4 costimulatory molecule-mediated negative regulation of T cell activation. Immunity. 2010;33:326–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schneider H, Downey J, Smith A, Zinselmeyer BH, Rush C, et al. Reversal of the TCR stop signal by CTLA-4. Science. 2006;313:1972–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer LV, de Jong DH, Holt A, Rzepiela AJ, de Vries AH, et al. Lipid packing drives the segregation of transmembrane helices into disordered lipid domains in model membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1343–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009362108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kusumi A, Nakada C, Ritchie K, Murase K, Suzuki K, et al. Paradigm shift of the plasma membrane concept from the two-dimensional continuum fluid to the partitioned fluid: high-speed single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:351–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andrews NL, Lidke KA, Pfeiffer JR, Burns AR, Wilson BS, et al. Actin restricts FcepsilonRI diffusion and facilitates antigen-induced receptor immobilization. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:955–63. doi: 10.1038/ncb1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Treanor B, Depoil D, Bruckbauer A, Batista FD. Dynamic cortical actin remodeling by ERM proteins controls BCR microcluster organization and integrity. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1055–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.James JR, White SS, Clarke RW, Johansen AM, Dunne PD, et al. Single-molecule level analysis of the subunit composition of the T cell receptor on live T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700411104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76*.Meilhac N, Destainville N. Clusters of Proteins in Biomembranes: Insights into the Roles of Interaction Potential Shapes and of Protein Diversity. J Phys Chem B. 2011 doi: 10.1021/jp1099865. Presents a general thermodynamic process for membrane proteins sorting into nanodomains and islands. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fahmy TM, Bieler JG, Edidin M, Schneck JP. Increased TCR avidity after T cell activation: a mechanism for sensing low-density antigen. Immunity. 2001;14:135–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schamel WW, Arechaga I, Risueno RM, van Santen HM, Cabezas P, et al. Coexistence of multivalent and monovalent TCRs explains high sensitivity and wide range of response. J Exp Med. 2005;202:493–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anikeeva N, Lebedeva T, Clapp AR, Goldman ER, Dustin ML, et al. Quantum dot/peptide-MHC biosensors reveal strong CD8-dependent cooperation between self and viral antigens that augment the T cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16846–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607771103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jain A, Liu R, Ramani B, Arauz E, Ishitsuka Y, et al. Probing cellular protein complexes using single-molecule pull-down. Nature. 2011;473:484–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]