Abstract

Our primary purpose in this study was to examine age differences in using choice deferral when young and older adults made trade-off decisions. Ninety-two young and 92 older adults were asked to make a trade-off decision among four cars or to use choice deferral (i.e., not buy any of these cars and keep looking for other cars). High and low emotional trade-off difficulty were manipulated between participants through different attribute labels of available cars. Older adults were more likely than young adults to choose deferral. Older adults who used deferral reported less retrospective negative emotion than those who did not.

Keywords: aging, trade-off decisions, choice deferral, negative emotion

Life is full of choices, whether between two flavors of jam or among 54 Medicare prescription drug plans. Some choices are relatively easy (e.g., if you know which flavor of jam you like better), and others are more difficult. Trade-off decisions are often difficult because individuals facing these types of decisions usually have to accept loss on certain attributes to obtain gain on other attributes. For example, to maximize the monetary saving goal when buying a car, sometimes you have to accept loss in style or safety concerns. When trade-off is difficult, individuals may use choice deferral, a situation in which they choose not to choose for the time being. Choice deferral may have serious consequences. For example, 25% of 43 million older adults failed to enroll in the Medicare prescription drug plan when it first became available (Winter et al., 2006). Young and older adults may experience decision-making processes differently because of older adults’ increased effectiveness of emotion regulation but decreased effectiveness of basic cognitive mechanisms (Mather, 2006). Our primary purpose in this study was to examine age differences in using choice deferral when young and older adults made trade-off decisions.

Most past decision-making research has focused on studying how people choose among a given set of alternatives. In reality, however, people also have a choice to not choose for the time being, which is referred to as choice deferral (Anderson, 2003). The limited research on choice deferral has found that trade-off decisions involving conflicts between attributes associated with highly valued goals (e.g., price, safety) usually lead to more choice deferral (Beattie & Barlas, 2001; Luce, 1998). Trade-off decisions frequently elicit negative emotions, such as anticipated regret and anticipatory emotions of fear, anxiety, and despair (Dhar, 1997; Gilovich & Medvec, 1995; Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001). Thus, coping with the negative emotion may become an important goal in decision making (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988), in addition to effort minimizing and accuracy maximizing (Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). Luce and colleagues (Luce, 1998; Luce, Bettman, & Payne, 1997) found that choice deferral may provide coping benefits such that the choice of an avoidant option may result in less retrospective negative emotion.

According to the socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999), older adults with a limited future time perspective are more likely than young adults to focus on emotion regulation goals in their lives. Research by Carstensen and colleagues (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Mather & Carstensen, 2005) has found that older adults are more likely than young adults to maintain positive emotions and avoid negative emotions. Blanchard-Fields, Camp, and Casper (1995) suggested that the emotional nature of problem situations becomes more salient with aging, and older adults are more likely than young adults to use avoidant problem-solving strategies across problems with various levels of emotional salience. In addition, a recent study by Chen and Ma (2009) found that anticipated emotions predicted risk taking differently for young and older adults. Specifically, anticipated positive emotions (e.g., anticipated happiness to gain) predicted older adults’ risky choices, but anticipated negative emotions (e.g., anticipated regret for missing out on the opportunity) predicted young adults’ risky choices. Thus, emotion seems to play an important role in age differences in decision-making processes.

Some evidence has also shown that older adults are more likely than young adults to avoid making decisions (Mather, 2006). Finucane et al. (2002) found that older adults were more likely than younger adults to say that they preferred not to have the responsibility for choosing a Medicare health plan. When faced with medical decisions, older adults were more likely than younger adults to indicate that they would rather not make the decisions themselves, instead leaving them up to the doctor (Curley, Eraker, & Yates, 1984; Ende, Kazis, Ash, & Moskowitz, 1989; Hudak et al., 2002; Steginga & Occhipinti, 2002). This may be because older adults feel less competent and knowledgeable than doctors in making medical decisions. In addition, Hudak et al. (2002) discovered that older adults tended to defer the decision to receive medical treatment until a later, undetermined date. Although the evidence typically centered on medical decisions that were highly emotion loaded, little research in the aging field has examined age differences in decision avoidance in other domains. Are older adults more likely to use choice deferral in general or just for medical domains? Would young and older adults differ in using choice deferral when emotion load is high than when it is low? To answer these questions, we used a car-purchasing task (Luce,1998) to examine age differences in choice deferral in a consumer choice domain.

In the car-purchasing task, young and older adults were asked to make a choice among four cars that varied in values of four attributes. Two levels of emotional trade-off difficulty were manipulated between subjects through attribute labels of available cars. The degree of trade-off difficulty depended on between-attribute conflicts. Attributes were higher in emotional trade-off difficulty when they were associated with more highly valued goals and higher loss aversion. Loss aversion was measured by the degree of reluctance to accept losses on certain attributes. Because certain attributes (e.g., safety) were emotionally more difficult to trade off with currency (e.g., money) than were other attributes (e.g., style), the high and low emotional trade-off difficulty conditions differed in loss aversion of available car attributes (Luce, 1998). In the high emotional trade-off difficulty condition, participants made a trade-off between price and attributes such as occupant survival and pollution caused. In the low emotional trade-off difficulty condition, they made a trade-off between price and attributes such as routine handling and recycling potential. Participants either made a choice among four cars or used choice deferral (i.e., to not buy any of these cars and keep looking for other cars). They also rated the extent to which they experienced negative emotions when making choices.

We should note that choice is not only an emotional process, but also a cognitive process. Henninger, Madden, and Huettel (2010) found that age-related decline in processing speed and memory accounted for age differences in decision making. In the present research, we manipulated emotional trade-off difficulty but kept cognitive load constant across the two conditions in studying choice deferral.

We had two major hypotheses: first, that older adults would be more likely than young adults to use choice deferral, especially when the emotional trade-off difficulty was high, and second, that negative emotions elicited by trade-off decisions would be reduced after using choice deferral for older adults. In addition, we compared young and older adults who used choice deferral with those who did not on a short form of the Maximization scale (Nenkov, Morrin, Ward, Schwartz, & Hulland, 2008). Maximization is the tendency to seek the best option and not settle for less (Schwartz et al., 2002). It is conceptualized as a unidimensional trait that influences decision making. People who are higher in maximizing tendency may be more likely to use choice deferral when it is difficult to find the best option. However, because of the lack of research on age differences in maximization and choice deferral, we made no specific hypothesis.

Method

Participants

Ninety-two young adults (age range = 18–25 years old, M = 20.83, SD = 1.45) from a Midwestern university and 92 community-dwelling older adults (age range = 60–86 years old, M = 70.45, SD = 6.97) from the surrounding area participated in the experiment. Young adults received extra credit for psychology classes, and older adults participated on volunteer basis. Young adults reported having more years of education (M = 13.27, SD = 1.34) than older adults (M = 12.80, SD = 2.18), t(179) = 9.15, p < .001. For self-rated health status (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = excellent), young adults rated themselves as more healthy (M = 3.30, SD = 0.61) than did older adults (M = 2.83, SD = 0.72), t(182) = 4.87, p < .001.

Decision-Making Task

We modified the car-purchasing task of Luce’s (1998) Experiment 1. In Luce, participants were asked to choose a car with five options that varied in four attributes or choose not to buy any car. Emotional trade-off difficulty was manipulated between subjects through pretested loss aversion to attribute labels of available cars. Loss aversion was measured as the degree of reluctance to accept loss on certain attributes. The pair of car attributes, occupant survival and pollution caused, in the high emotional trade-off difficulty condition were rated with higher loss aversion than were the other pair of car attributes, routine handling and sound system, in the low emotional trade-off difficulty condition. In addition, Luce used price and styling as the constant car attributes between the two emotional trade-off difficulty conditions.

Because this research included both young and older adults, we conducted a pilot study to test age differences in loss aversion of car attributes. Sixty young college students between 18 and 27 years old (M = 20.55, SD = 1.68) and 30 older adults between 62 and 84 years old (M = 70.13, SD = 5.37) participated in the pilot study. Young adults reported having more years of education (M = 14.61, SD = 2.16) than older adults (M = 13.39, SD = 2.31), t(88) = 2.41, p < .01. On self-rated health status, young adults rated themselves as more healthy (M = 3.27, SD = .55) than did older adults (M = 2.53, SD = 0.78), t(88) = 4.67, p < .0001.

There were 15 car attributes (e.g., occupant survival, styling, maintenance costs). The attributes’ value ranged from worst, very bad, bad, average, good, and very good to best. Participants were asked to rate “how reluctant you are to give up a best value for a worst value on each attribute when you choose a new car?” on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not reluctant at all to 7 = very reluctant). Because age differences were found on styling and sound system, we selected interior roominess to substitute for styling as the constant attribute across two conditions and recycling potential to substitute for sound system in the low trade-off condition. We performed paired t tests to test loss aversion for the two pairs (i.e., occupant survival vs. routine handling and pollution caused vs. recycling potential) in the high versus low trade-off conditions. We found significant differences in loss aversion for both pairs: occupant survival (M = 5.38, SD = 2.29) was rated higher than routine handling (M = 4.87, SD = 1.58) on loss aversion, t(89) = 2.80, p < .01, and pollution caused (M = 4.19, SD = 1.40) was rated higher than recycling potential (M = 3.71, SD = 1.57) on loss aversion, t(89) = 2.45, p < .05.

In the target experiment, participants were asked to

imagine that you need to purchase a new car due to the breakdown of your current car. You looked up the various attributes of a car in the Consumer Reports and went to shop for the car at a number of dealerships in your area. There were four cars that you were interested in and they varied in four attributes: price, occupant survival (or routine handling), interior roominess, and pollution caused (or recycling potential).

The definitions of the four attributes and possible values were also explained in the instructions. After seeing the four cars displayed in a table (see Table 1 for the cars in the high emotional trade-off difficulty and the low emotional trade-off difficulty conditions), participants were asked to make a choice among four cars or use choice deferral (i.e., not buy any of these cars and keep looking for other cars).

Table 1.

Four Cars in the High Emotional Difficulty and Low Emotional Difficulty Conditions

| Attribute |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car | Price | Occupant survival |

Interior roominess |

Pollution caused |

| High emotional difficulty condition | ||||

| A | Very poor | Very good | Average | Very good |

| B | Average | Average | Best | Poor |

| C | Best | Worst | Very poor | Average |

| D | Worst | Best | Poor | Worst |

|

| ||||

| Price | Routine handling |

Interior roominess |

Recycling potential |

|

|

| ||||

| Low emotional difficulty condition | ||||

| A | Very poor | Very good | Average | Very good |

| B | Average | Average | Best | Poor |

| C | Best | Worst | Very poor | Average |

| D | Worst | Best | Poor | Worst |

Immediately after participants made their choices for car purchasing, they were asked to read a list of adjectives that described different feelings and emotions (11 negative emotions). Seven negative emotions were taken from Watson, Clark, and Tellegen’s (1988) Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and four were added because of their relevance to the car-purchasing task (i.e., regretful, worried, uneasy, and avoidant). Participants were asked to “rate the extent to which you have felt this way while making your decision” on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = a little and 5 = very much). The internal consistency of the 11 negative emotions was relatively high (α = .90).

Short Form of the Maximization Scale (Nenkov et al., 2008)

After the decision-making task, young and older adults also completed a six-item Maximization Scale to assess “how people made decisions in their everyday lives.” Nenkov et al. (2008) found that the short form performed better in reliability and validity than the original 13-item Maximization Scale (Schwartz et al., 2002). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree). Some sample items were “I often find it difficult to shop for a gift for a friend” and “I never settle for second best.”

Design and Procedure

We used a 2 (age group: young vs. older) × 2 (emotional trade-off difficulty conditions: high vs. low) between-subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned to either the high or the low emotional trade-off difficulty condition in each age group, resulting in the same number of young and older adults in each condition. They first filled out a demographic questionnaire and then completed the decision-making task. There was no time restriction on the decision-making task. Participants took as much time as they needed to read the descriptions and make their choices. After the decision-making task, they completed a six-item Maximization scale. Finally, they were debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Results

Age Differences in Choice Deferral

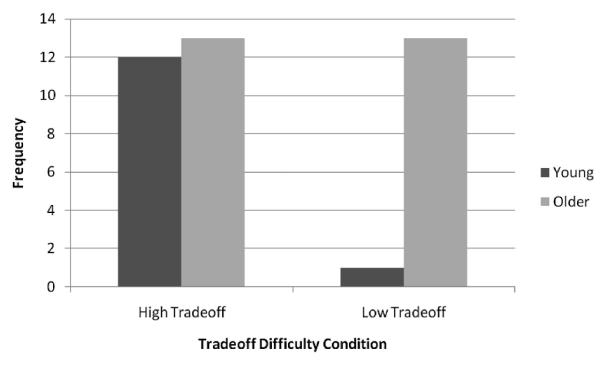

To examine age differences in choice deferral, we recoded choices into deferral choices: 1 for yes and 0 for other choices. A 2 (age group: young vs. old) × 2 (emotional trade-off difficulty conditions: high vs. low) logit analysis was performed on the choices. Supporting the first hypothesis, older adults were more likely than young adults to use choice deferral: χ2(1, N = 184) = 6.60, p < .05, Φ = .19. There was also a main effect of emotional trade-off difficulty condition: Participants in the high trade-off difficulty condition made more choice deferral than those in the low trade-off difficulty condition: χ2(1, N = 184) = 5.67, p < .05, Φ = .18. Furthermore, the Age Group × Emotional Trade-off Difficulty Condition interaction effect was significant, χ2(1, N = 184) = 5.67, p < .05, Φ = .18. Older adults chose the deferral option regardless of emotional trade-off difficulty. In contrast, young adults were more likely to use choice deferral in the high trade-off difficulty condition than in the low trade-off difficulty condition (see Figure 1 for frequencies of the deferral choices).

Figure 1.

Frequencies of the deferral choices by age group and emotional trade-off difficulty condition.

Age Group and Choice Deferral Effects on Retrospective Negative Emotions

To test whether young and older adults who used choice deferral showed different degrees of retrospective negative emotion from those who did not, we conducted a 2 (age group: young vs. old) × 2 (choice deferral: yes vs. no) analysis of variance on retrospective negative emotion, averaged across 11 negative emotions. Only the interaction effect was significant, F(1, 178) = 5.00, p < .05, ηp2 = .03. Older adults reported less retrospective negative emotion with the deferral choices (M = 1.78, SD = 0.88) than those who made other choices (M = 2.22, SD = 1.18, Cohen’s d = −0.39), whereas young adults reported more negative emotion when they used choice deferral (M = 2.42, SD = 1.50) than those who did not (M = 1.97, SD = 0.89, Cohen’s d = 0.45). Supporting the second hypothesis, the negative emotions elicited by trade-off decisions were reduced for older adults who used choice deferral.

Age Group and Choice Deferral Effects in Maximization

To explore whether young and older adults differ in maximization and choice deferral, we performed a 2 (age group: young vs. old) × 2 (choice deferral: yes vs. no) analysis of variance on the maximization tendency, averaged across six items. The main effect of age group was significant, F(1, 175) = 7.62, p < .01, ηp2 = .04. Older adults (M = 3.12, SD = 0.54) were overall lower on the maximization tendency than young adults (M = 3.25, SD = 0.54). More important, there was a significant Age Group × Choice Deferral interaction, F(1, 175) = 5.53, p < .05, ηp2 = .03. Older adults who chose the deferral option (M = 2.99, SD = 0.61) showed less maximization tendency than those who made other choices (M = 3.17, SD = 0.50). In contrast, young adults who used choice deferral (M = 3.51, SD = 0.53) showed higher maximization tendency than those who did not (M = 3.21, SD = 0.54).

Discussion

Most past decision-making research focused on individuals’ choices. However, recent social phenomena suggest that studying decision avoidance is just as important. This research is the first to systematically examine age differences in choice deferral when young and older adults face emotionally difficult trade-off decisions. Older adults were found to be more likely than young adults to use choice deferral in a typical consumer scenario of car purchasing, extending the previous findings in the medical domain (Mather, 2006). In addition, older adults preferred choice deferral regardless of emotional trade-off difficulty, whereas young adults used more choice deferral in the high than in the low emotional trade-off difficulty conditions. This pattern of age differences in decision making parallels the results of Blanchard-Fields et al. (1995) in everyday problem solving: Older adults were more likely to use avoidant strategies for problems across various levels of emotional saliency, whereas young adults were more likely to use avoidant strategies only for problems with high emotional saliency.

Results of this study were consistent with our hypothesis that older adults might use choice deferral to regulate the negative emotions elicited by difficult trade-off decisions. We found that older adults who used choice deferral reported fewer retrospective negative emotions than those who made other choices. One explanation for this finding is that older adults might be more likely than young adults to focus on emotion regulation goals. The desire to avoid negative emotions such as anticipated regret has been proposed to be the motivation behind many decisions (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995; Loewenstein et al., 2001). The emotion regulation goals may be especially salient for older adults who have to make emotionally difficult trade-off decisions.

On the contrary, young adults reported slightly higher retrospective negative emotions after they used choice deferral than did those who made other choices. This result was somewhat unexpected and a departure from earlier research (Luce, 1998). It may have something to do with the measure of retrospective negative emotion. The self-reported negative emotions were all below the midpoint of the scale. Clearly, participants may not experience any strong negative emotions in a laboratory setting. Thus, the result may simply be an artifact of the artificial laboratory situation. Alternatively, it might be that young adults were less likely than older adults to use choice deferral as a way to cope with negative emotions elicited by difficult trade-off decisions. The interaction of age group and choice deferral on maximization tendency seemed to support the latter explanation. Young adults who chose the deferral options were higher on maximization than those who did not. They might be the true “maximizers” who kept searching for the optimal choice and never settled for second best.

The results of this study may be interpreted with its limitations in mind. One big limitation is that the artificial car-purchasing task carries few consequences in real life. When young and older adults face important decisions in real-world situations such as whether to undergo medical treatments or actually purchase a new car, choice deferral may cause serious consequences that are highly emotionally loaded (Tversky & Shafir, 1992). Future research should use more realistic decision tasks across multiple domains to study age differences in choice deferral.

Another limitation of this study was the lack of cognitive measures. Compared with young adults, older adults are reported to have reduced working memory capacity (Salthouse, 1996). The 4 × 4 table of car attributes may exceed older adults’ working memory capacity, and they may thus have used choice deferral more frequently than young adults. Future research may assess both the working memory capacity and the negative emotion elicited to account for age differences in choice deferral.

References

- Anderson C. The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:139–167. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.139. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie J, Barlas S. Predicting perceived differences in tradeoff difficulty. In: Weber E, Baron J, Loomes G, editors. Conflict and tradeoffs in decision making. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 25–64. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F, Camp C, Casper JH. Age differences in problem- solving style: The role of emotional salience. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:173–180. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.2.173. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.10.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ma X. Age differences in risky decisions: The role of anticipated emotions. Educational Gerontology. 2009;35:575–586. doi: 10.1080/03601270802605291. doi:10.1080/03601270802605291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley SP, Eraker SA, Yates JF. An investigation of patients’ reactions to therapeutic uncertainty. Medical Decision Making. 1984;4:501–511. doi:10.1177/0272989X8400400412. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R. Consumer preference for a no-choice option. Journal of Consumer Research. 1997;24:215–231. doi:10.1086/209506. [Google Scholar]

- Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz MA. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: Decision-making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1989;4:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02596485. doi:10.1007/BF02596485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane ML, Slovic P, Hibbard JH, Peters E, Mertz CK, Macgregor DG. Aging and decision-making competence: An analysis of comprehension and consistency skills in older versus younger adults considering health-plan options. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2002;15:141–164. doi:10.1002/bdm.407. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:466–475. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T, Medvec VH. The experience of regret: What, when, and why. Psychological Review. 1995;102:379–395. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.379. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger D, Madden D, Huetel S. Processing speed and memory mediate age-related differences in decision making. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:262–270. doi: 10.1037/a0019096. doi:10.1037/a0019096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudak PL, Clark JP, Hawker GA, Coyte PC, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, Wright JG. You’re perfect for the procedure! Why don’t you want it?” Elderly arthritis patients’ unwillingness to consider total joint arthroplasty surgery: A qualitative study. Medical Decision Making. 2002;22:272–278. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce MF. Choosing to avoid: Coping with negatively emotion-laden consumer decisions. Journal of Consumer Research. 1998;24:409–433. doi:10.1086/209518. [Google Scholar]

- Luce MF, Bettman JR, Payne JW. Choice processing in emotionally difficult decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1997;23:384–405. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.2.384. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.23.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. A review of decision-making processes: Weighing the risks and benefits of aging. In: Carstensen LL, Hartel CR, editors. When I’m 64: Committee on aging frontiers in social psychology, personality, and adult developmental psychology. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenkov GY, Morrin M, Ward A, Schwarz B, Hulland J. A short form of the maximization scale: Factor structure, reliability, and validity studies. Judgment and Decision Making. 2008;3:371–388. [Google Scholar]

- Payne JW, Bettman JR, Johnson EJ. The adaptive decision maker. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review. 1996;103:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B, Ward A, Monterosso J, Lyubomirsky S, White K, Lehman DR. Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1178–1197. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1178. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steginga SK, Occhipinti S. Decision making about treatment of hypothetical prostate cancer: Is deferring a decision and expert-opinion heuristic? Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2002;20:69–84. doi:10.1300/J077v20n03_05. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Shafir E. Choice under conflict: The dynamics of deferred decision. Psychological Science. 1992;3:358–361. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00047.x. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J, Balza R, Caro F, Heiss F, Jun B, Matzkin R, McFadden D. Medicare prescription drug coverage: Consumer information and preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:7929–7934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601837103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601837103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]