Abstract

Hypertrophic scar (HTS) is a dermal form of fibroproliferative disorder which often develops after thermal or traumatic injury to the deep regions of the skin and is characterized by excessive deposition and alterations in morphology of collagen and other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. HTS are cosmetically disfiguring and can cause functional problems that often recur despite surgical attempts to remove or improve the scars. In this review, the roles of various fibrotic and anti-fibrotic molecules are discussed in order to improve our understanding of the molecular mechanism of the pathogenesis of HTS. These molecules include growth factors, cytokines, ECM molecules, and proteolytic enzymes. By exploring the mechanisms of this form of dermal fibrosis, we seek to provide some insight into this form of dermal fibrosis that may allow clinicians to improve treatment and prevention in the future.

Keywords: Hypertrophic scar, TGF-β, Cytokines, Decorin, Matrix metalloproteinases

Introduction

Hypertrophic scars (HTS) are often caused by trauma and burn injury to the deep dermis and are itchy, raised, painful, rigid and disfiguring scars. Unlike keloids which progress beyond the original area of injury (Atiyeh et al. 2005), HTS remain within the boundary of the original injury. In many cases, HTS occurs at the site of injury resulting in cosmetic disfigurement or when present in mobile regions of the skin, it can cause contractions that often result in limitation of joint mobility. These difficulties can lead to psychological and social issues for burn survivors (Engrav et al. 2007; Bombaro et al. 2003; De et al. 2009) (See Fig. 1). In this review, we have focused specifically on HTS and try to clarify the molecular mechanism of HTS, which would be helpful in developing new prevention and therapeutic treatments for people with HTS following injury.

Fig. 1.

Ten year old male with hypertrophic scar to the chest and flank 16 months following a burn injury

Wound healing and the pathological features of HTS

Wound healing can be divided into four stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and tissue remodeling (Reinke and Sorg 2012). In these four stages, there are complicated interactions within a complex network of profibrotic and antifibrotic molecules, such as growth factors, proteolytic enzymes and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (Miller and Nanchahal 2005; Werner and Grose 2003). Each molecule plays its own part in the different phases of the wound healing process. As soon as the injury occurs, the hemostasis process begins and the bleeding is controlled by the aggregation of platelets at the site of injury. The subsequent formation of the fibrin clot helps stop the bleeding and provides a scaffold for the attachment and proliferation of the cells. Growth factors and cytokines are mainly secreted by the inflammatory cells and they contribute to the initiation of the proliferative phase of wound healing. Later, angiogenesis and collagen synthesis followed by tissue remodeling complete the stages of the wound healing process.

The delicate balance of deposition and degradation of ECM protein will be disrupted when either excessive production of collagen, proteoglycans and fibronectin by fibroblasts or deficient degradation and remodeling of ECM occurs (Tredget 1999). HTS occurs when the inflammatory response to injury is prolonged, leading to the pathological characteristics of HTS including increased vascularization, hypercellularity and excessive collagen deposition (Tredget et al. 1997; Wang et al. 2011a, b; Armour et al. 2007). Our research group has also found decrease in the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP), decorin and increased transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) expression in HTS (Honardoust et al. 2012a, b).

Differences in cellular characteristics of normal dermal and HTS fibroblasts

Fibroblasts are the most common cells in connective tissue and are one of the key elements in wound healing. The main function of fibroblasts is to maintain the physical integrity of connective tissue, participate in wound closure as well as produce and remodel ECM (McDougall et al. 2006; Kwan et al. 2009). However, fibroblasts from HTS behave quite differently than normal fibroblasts. HTS tissue has greater amounts of fibroblasts that exhibit an altered phenotype than normal skin (Nedelec et al. 2001). HTS fibroblasts show higher expression of TGF-β1 than normal fibroblasts (Scott et al. 1995). The increase or prolonged activity of TGF-β1 leads to an overproduction and excess deposition of collagen by fibroblasts that often result in HTS formation (Shah et al. 1995). HTS fibroblasts have demonstrated reduced mRNA for collagenase as well as net reductions in the ability to digest soluble collagen as compared to their normal paired fibroblasts (Ghahary et al. 1996). HTS fibroblasts are also found to have a reduced ability to synthesize nitric oxide, an important mediator of growth factor signaling, which regulates wound healing and collagenase through its antiproliferative and antimicrobial effects (Wang et al. 1996).

HTS fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts and can account for increased ECM synthesis and contraction of tissue. They are a particular phenotype which differ from fibroblasts by their expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Nedelec et al. 2001). HTS myofibroblasts are less sensitive to apoptotic signals, coupled with their ability to produce more collagen and less collagenase than fibroblasts, which may play an important role in HTS formation (Nedelec et al. 2000; Moulin et al. 2004).

Matrix metalloproteinase-1, 2, 9 (MMP-1, 2, 9) are involved in the formation of HTS regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs)

The MMPs are a number of zinc-dependent proteinases, which are known for their critical role in the tissue remodeling process (Das et al. 2003; Yuan and Varga 2001). The most particular characteristic of MMPs is the function of the proteolytic cleavage of collagen and degradation of other elements of the ECM (Chakraborti et al. 2003). There are at least 23 types of MMPs. TIMPs are the specific proteins that regulate the function of MMPs and four specific types of TIMPs exist which block the activity of MMPs by binding to them in a 1:1 ratio (Stamenkovic 2003).

The over-expression of MMPs could result in an imbalance between ECM production and degradation, which could lead to chronic ulcers (Saito et al. 2001). Alternately, the alterations of MMPs and TIMPs expression could cause liver cirrhosis, the result of a reduction of collagen degradation and excessive accumulation of ECM (Lichtinghagen et al. 2001). As mentioned, TGF-β1 acts as a potent inducer of the differentiation of myofibroblasts by stimulating the expression of α-SMA and it reduces the activity of MMPs by stimulating TIMPs synthesis in fibroblasts. In this way, the degradation process of ECM by MMP is abrogated. Meanwhile, the ECM deposition by fibroblasts is promoted by TGF-β1. All of these features contribute to the formation of HTS (Desmoulière et al. 1993).

Many types of MMPs and TIMPs are considered to be related to HTS formation. Several studies showed that MMP-1 expression is decreased in HTS, an important transcriptional change in HTS, and its reversal could be a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of HTS (Reynolds 1996; Xie et al. 2008; Eto et al. 2012). Ghahary et al. showed that differentiated keratinocyte-releasable stratifin (14-3-3 sigma) could stimulate MMP-1 expression in dermal fibroblasts through c-fos and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Lam et al. 2005), which may control degradation of the major dermal ECM components and provide useful targets for clinical intervention of HTS formation (Ghahary et al. 2005). However, this stimulatory effect could be suppressed by insulin treatment (Lam et al. 2004). A subsequent study showed that the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were up-regulated by the interaction between fibroblasts and keratinocytes, which may favor resolution of accumulated ECM components (Sawicki et al. 2005).

An early study showed that decreased expression of TIMP-1 with the subsequent increased secretion of MMPs caused delayed healing of chronic ulcers (Vaalamo et al. 1999). A study using athymic nude mice as an animal model showed that MMP-9 was up-regulated in scarless wound healing (Manuel and Gawronska-Kozak 2006). Similar experiments demonstrated that the expressions of MMP-1 and MMP-9 were highly regulated in scarless fetal rat wounds (Dang et al. 2003). A human study of HTS, keloids, atrophic scars from different patients and different regions of the body suggested that MMP-9 played a leading role in scar-free healing (Tanriverdi-Akhisaroglu et al. 2009). A more recent study showed that by transfection of Smad interacting protein 1 (SIP1) to the HTS fibroblasts, MMP-1 expression was up-regulated while collagen type I α2 (COL1A2) was decreased. As well, the knockdown of SIP1 in normal fibroblasts up-regulated COL1A2 levels induced by TGF-β 1. All these findings suggest that SIP1 could be a regulator of skin fibrosis and SIP1 depletion in HTS could result in the up-regulation of COL1A2 and the down-regulation of MMP-1, leading to excessive accumulation of ECM along with formation of HTS (Zhang et al. 2011b). Decreased levels of MMP-2, MMP-9 and increased levels of TIMP-1 were found in patients with HTS suggesting that the elevated systemic TIMP-1 concentration might contribute to tissue fibrosis, leading to HTS formation (Ulrich et al. 2003). A recent experiment compared TIMP-1 expression in normal skin and HTS, and the result exhibited relatively strong expression of TIMP-1 in HTS biopsies in contrast with very low levels of TIMP-1 in normal skin (Simon et al. 2012).

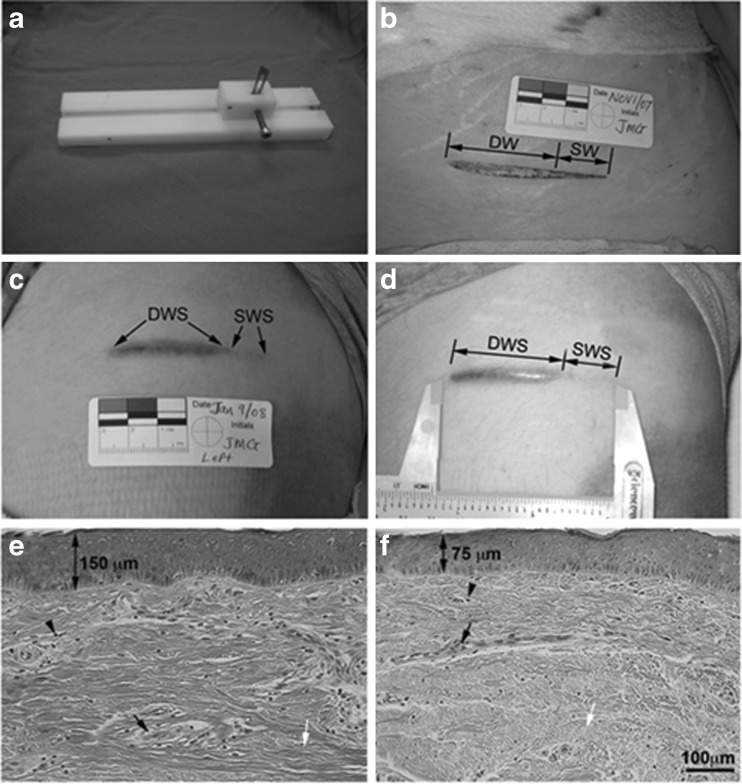

Depth of dermal injury is an important factor leading to HTS formation

The depth of injury is critical to HTS formation and of great clinical importance. The difference between superficial and deep injuries determines how these wounds heal and the severity of the scarring (Monstrey et al. 2008). Superficial wounds generally heal within 2 weeks without HTS formation and surgical treatment while deep wounds are prone to HTS and often require surgical interventions such as skin grafting and/or anti-scar procedures. In an experimental dermal scratch model done by the author’s laboratory (Honardoust et al. 2012a; Dunkin et al. 2007), a specially designed and constructed jig was used to create progressively deeper wounds on a burn patient after informed consent. The wounds were along the lines of relaxed skin tension and were 6 cm long, 0 to 0.75 mm deep at one end (superficial wound) and 0.76 to 3 mm deep (deep wound) at the other end. The superficial wound of the wound scratch model healed with minimal scarring while the deep wound resulted in HTS that were red, raised, itchy scar confined to the site of injury. This result suggests there is a critical value of depth of the injury beyond which scar formation rather than tissue regeneration occurs (See Figs. 2 and 3). Thus, these findings suggest that deep dermal fibroblasts are responsible for HTS formation and maybe the source of the previously described characteristic HTS fibroblast.

Fig. 2.

Regeneration occurs in superficial wounds while scarring occurs in deeper wounds (From Kwan P, Hori K, Ding J, Tredget EE (2009) Scar and contracture: biological principles. Hand Clin 25(4):511–28; with permission)

Fig. 3.

Creation of deep and superficial scratch wounds and histological analysis of resulted scars. a Jig used to create the scratch wound model. b Wound created on the anterior thigh. c Scratch wound 70 days post-wounding. d Deep and superficial wound scar. e Deep wound scar tissue stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). f Superficial wound scar tissue stained with H&E. Double-headed arrows in E and F indicate average thickness of epithelium. Arrowheads point to cells. Black arrows point to blood vessels. White arrows point to collagen. DW, deep wound; SW, superficial wound; DWS, deep wound scar; SWS, superficial wound scar (From Honardoust D, Varkey M, Marcoux Y, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE (2012) Reduced decorin, fibromodulin, and transforming growth factor-β3 in deep dermis leads to hypertrophic scarring. J Burn Care Res 33(2):218–27; with permission)

Deep dermal fibroblasts resemble HTS fibroblasts

Superficial and deep dermal fibroblasts are derived from the papillary and reticular layers respectively and can be examined by using dermatomes to harvest different layers of the skin. Fibroblasts from the two layers exhibit heterogeneity, which may contribute to various outcomes of healing with different depths of injury (Sorrell and Caplan 2004). For example, injuries to the deep dermis where deep dermal fibroblasts are found most abundant often lead to the development of HTS; whereas, superficial wounds injuring and activating a large number of superficial fibroblasts heal with little or no scar formation. Work published by our group proposed that deep dermal fibroblasts accounted for wound healing and HTS formation in deep thermal injuries where superficial fibroblasts were completely destroyed by the injury (Scott et al. 2000). Deep dermal fibroblasts produce more collagen (Ali-Bahar et al. 2004), proliferate slower (Feldman et al. 1993) and have less collagenase (Wang et al. 2008b) compared to superficial fibroblasts. Deep dermal fibroblasts also produced more α-SMA than superficial fibroblasts while it is all known that HTS fibroblasts are characterized by increased collagen synthesis and α-SMA expression. All of these provide evidence for the fibrotic characteristics of deep dermal fibroblasts, which suggest a similar behavior between deep dermal fibroblasts and HTS fibroblasts. Studies conducted by our group showed that TGF-β and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, also known as CCN2) (Wang et al. 2008b), two key profibrotic cytokines, were produced in greater quantities by deep dermal fibroblasts, which resembled a similar increase in the production of HTS fibroblasts (Wang et al. 2000). Thus, deep dermal fibroblasts resemble HTS fibroblasts and have similar biological functions distinctly different from superficial fibroblasts.

TGF-β isoforms are involved in HTS formation through the smad pathway

TGF-β is a secreted protein that exists in three distinct isoforms in mammals, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 (Bock et al. 2005). Each isoform has a unique function in the wound healing process. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 are secreted from degranulated platelets, as well as monocytes and macrophages, while TGF-β3 is produced by keratinocytes. In normal tissue, the TGF-β isoforms exist as latent precursors where they are bound to latent TGF-β1 binding proteins (LTBP) (Annes et al. 2003). Initially, it was thought that TGF-β contributed to wound healing by the stimulation of angiogenesis, proliferation of fibroblasts, differentiation of myofibroblasts and synthesis of collagen as well as deposition of ECM (McGee et al. 1989; Roberts et al. 1986). However, further experiments have shown that TGF-β plays an important role as a mediator in many diverse fibrotic disorders including pulmonary fibrosis, scleroderma (Broekelmann et al. 1991) and HTS (Ghahary et al. 1995b). In burn patients who developed HTS, the serum level of TGF-β was up-regulated locally and systemically (Tredget et al. 1998).

Shah et al. have shown that the two isoforms of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 induce the formation of HTS (Shah et al. 1994) and the conclusion was consistent with the findings from Wang et al. (Wang et al. 2000). However, in adult rat incisional wounds treated with neutralizing antibodies of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 reduced scarring occurred with the reduction of ECM deposition. Neutralization of either TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 did not have the same anti-scarring effect as neutralization of both TGF-β1 and TGF-β2. However, another experiment conducted by Shah et al. also suggested that TGF-β3 inhibited scarring, indicating the TGF-β3 might be the antagonist of the other two TGF-β isoforms (Shah et al. 1995). A more recent study by Leonard Lu et al. supported their findings. Rabbit ear wounds were treated intradermally with anti-TGF-β1, 2, 3 antibodies at three different points and the result showed different effects in different periods of the wound healing process. Early treatment showed delayed wound healing while treatment in the middle or later stages of wound healing significantly reduced HTS. The impaired wound healing in the early stage indicated that TGF-β isoforms were critical in the early phase of wound healing (Lu et al. 2005). TGF-β has multiple surface receptors, but TGF-β receptor I (TGF-βRI) and TGF-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) appear to be the predominant forms. TGF-βRI was found to be increased while TGF-βRII was decreased in HTS (Bock et al. 2005). Another experiment verified that truncated TGF-βRII could inhibit scar formation in rat wounds (Liu et al. 2005).

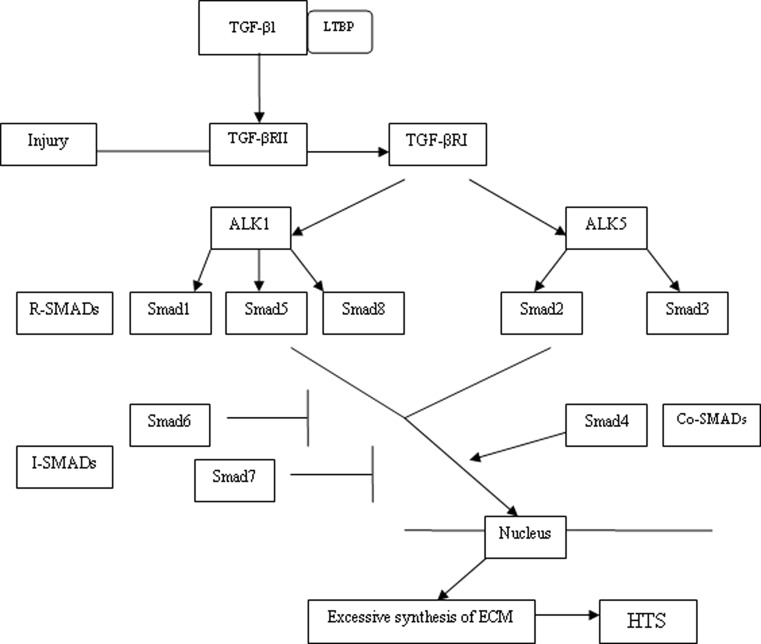

There are various types of signaling pathways for TGF-β1. The most important one is the Smad pathway (See Fig. 4). Smads are intracellular regulatory signal transduction proteins that respond to activation of the TGF-β receptor complex. Smad proteins can be classified into three categories, the receptor-regulated Smads (R-SMADs), the common mediator Smads (Co-SMADs) and the inhibitory Smads (I-SMADs) (Kopp et al. 2005). Classically, intracellular signaling of TGF-β1 is initiated after LTBP is dissociated from the complex. The activated TGF-β1 is released and binds to TGF-βRII, which then activates the TGF-βRI. These two receptors are a ligand-dependent complex of heterodimeric transmembrane serine/threonine kinases. There are two isoforms of TGF-βRIs that are involved in the signaling pathway known as activin-receptor-like kinase 1 and 5 (ALK 1 and ALK 5) (Pannu et al. 2007). The signaling pathway progresses when R-SMADs are phosphorylated by ALK 1 and ALK 5 respectively (ALK1 phosphorylates Smad 1, 5, 8 and ALK5 phosphorylates Smad 2, 3). The activated R-SMADs combine with the common mediator Smad 4 and then translocate into the nucleus where they function as transcription factors or participate in transcriptional control of other specific genes involved. I-SMADs (Smad 6 and Smad 7) antagonize the effects of the other two types of Smads, the R-SMADs and Co-SMADs by binding to TGF-βRI. In this way, phosphorylation of the R-SMADs and Smad 4 are inhibited. Thus, I-SMADs are considered to be the negative feedback regulators in the signaling pathway (Stopa et al. 2000). Decreased expression of Smad 7 in primary fibroblasts appears to decrease expression of type I collagen (COL1) and type III collagen (COL3) in a number of inflammatory disorders leading to fibrosis (Monteleone et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2002). Non-Smad signaling pathways such as MAPK, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) and the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway have also been implicated with TGF-β signaling, but the exact mechanisms are not yet clear (Moustakas and Heldin 2005; Klass et al. 2009).

Fig. 4.

The TGF-β1 Smad signaling pathway contributes to HTS. TGF-βRI is activated after TGF-β1 binds to TGF-βRII. R-SMADs are then phosphorylated by ALK1 and ALK 5, two isoforms of TGF-βRI. The activated R-SMADs bind with Smad 4 and then translocate into nucleus and act as transcription factors. I-SMADs antagonize the effects of the R-SMADs and Co-SMADs

The abnormal intracellular signaling of TGF-β1 is thought to initiate HTS by inducing the fibroblasts to excessively synthesize ECM and regulate CCN2, a downstream mediator of TGF-β1 (Massagué 1998; Xu et al. 2004; Shi-wen et al. 2006; Klass et al. 2009). In chronic wound conditions, TGF-β1 also has its influence, as the fibroblasts manifest an aberrant signaling pathway and decrease receptor expression, especially TGF-βRII (Kim et al. 2003). As the main component of TGF-β1 signaling pathway, overexpression of Smad proteins leads to the increased expression of COL1, COL3 and type IV collagen (COL4) (Cutroneo 2007). Importantly, Smad 3 knock out mice demonstrate faster wound healing, increased epithelialization and anti-scarring effects (Ashcroft et al. 1999; Bonniaud et al. 2004). Another study has shown that caveolin 1, one of the major coating proteins affecting TGF-β internalization and metabolism could inhibit TGF-β1 by preventing Smad signaling in fibroblasts derived from HTS (Lee et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2011a). A study conducted by our group recently showed that TGF-β inducible early gene 1 (TIEG1) knock out mice had a delay in wound closure due to impairment in wound contraction, granulation tissue formation, collagen synthesis and re-epithelialization, as well as increased Smad 7 in the wounds, which suggested a novel role of TIEG1 in dermal wound healing through the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway (Hori et al. 2012). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) can also induce an increase in TGF-β mRNA and protein (Ghahary et al. 1998a). Mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptors (M6P/IGF II-R) were found to be involved in latent TGF-β1 activation (Ghahary et al. 1999; Yang et al. 2000). As well, it was shown by our group that M6P/IGF II-R could facilitate the functional effect of IGF-1-induced latent TGF-β1 on dermal fibroblasts (Ghahary et al. 2000) and a subsequent study has shown that latent TGF-β1 may directly modulate fibroblast proliferation by a cell membrane dependent mechanism (Ghahary et al. 2002). In cell experiments, primary cultured dermal keratinocytes were genetically modified to express high levels of TGF-β1 (Ghahary et al. 1998b). A later experiment co-cultured dermal fibroblasts with genetically modified keratinocytes, the result showed that latent and active TGF-β1 could modulate ECM expression by overriding the effects of normal keratinocytes on the behavior of dermal fibroblasts (Bauer et al. 2002). Study using keratin 14-promoted TGF-β1 transgenic mice showed excessive latent TGF-β1 production in the epidermal layer of the skin where wounds exhibited a delay in re-epithelialization and early dermal fibrosis (Chan et al. 2002). Introduction of the latent TGF-β1 gene into keratinocytes markedly increased the release and activation of TGF-β after burn injury (Yang et al. 2001). Thus, a central role of TGF-β1 in the formation of HTS appears warranted.

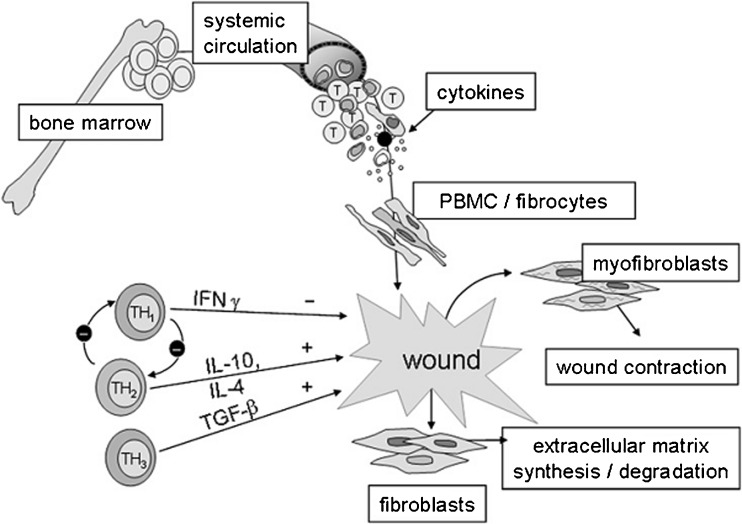

Systemic response of Th1, Th2 and Th3 to HTS formation

The development of HTS involves a complicated interaction between inflammation and the immune response. Recent research suggests that it is not only the severity of inflammation, but the type of immune response links to the fibrotic conditions (Wynn 2004). Wounds of thymectomized rats depleted of CD4+ lymphocytes showed a significant decrease in ultimate strength, resilience and toughness while wounds of animals depleted of CD8+ lymphocytes showed a significant increase in ultimate strength, resilience and toughness, suggesting that CD4+ lymphocytes play a very important role in wound healing (Davis et al. 2001). As well, it is known that CD4+ T lymphocytes predominate in HTS tissue with less CD8+ T lymphocytes (Castagnoli et al. 2002). Once activated by antigen presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, CD4+ T lymphocytes could differentiate into five subtypes of cells know as Th1, Th2, Th3, Th17 and T regulatory cells. Th1 and Th2 cells are the main subtypes defined in the murine model and each has a distinct cytokine profile (Mosmann and Coffman 1989). Th1 cells express interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-12 while Th2 cells express IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10. Th1 cytokines contribute to increased collagenase activity and matrix remodeling, which is antifibrotic and in contrast, Th2 cytokines are known to be profibrotic (Doucet et al. 1998). According to the different effects caused by Th1 and Th2 cytokines, HTS fibroblasts are subject to a Th2 influence by presenting reduced collagenase activity and reduced NOS activity (Wang et al. 1996).

A burn mouse model showed diminished production of IL-2 and a shift in the Th2 phenotype with increased production of IL-4 and IL-10, indicating an inhibitory effect on Th1 function (O’Sullivan et al. 1995). Our group examined the Th1/Th2 cytokine ratio of 12 burn patients with HTS 4 weeks post-burn which showed a significant decrease in the Th1/Th2 ratio compared with 13 controls. The IL-4 levels in the patient group were significantly higher than controls and IFN-γ levels were significantly lower at 1 month post-burn, suggesting a role of the Th2 cytokine following burn injury (Kilani et al. 2005). Another study detected serum cytokine levels from 22 burn patients showed elevated Th2 levels of IL-4 and IL-10, and reduced Th1 levels of IFN-γ and IL-12. IL-4 mRNA levels in HTS tissue was increased, while IFN-γ mRNA levels were decreased compared to normal skin (Tredget et al. 2006).

Another study reported an increase in the frequency of CD4+/TGF-β-producing T cells in the peripheral blood and HTS of burn patients (Wang et al. 2007c). Medium derived from CD4+ T lymphocytes of burn patients was used to treat cultured dermal fibroblasts and results showed increased cell proliferation, collagen synthesis and α-SMA as well as a significant up-regulation of TGF-β compared to fibroblasts treated with medium derived from the CD4+ T lymphocytes of normal subjects. We suspect that these CD4+/TGF-β-producing T cells are identical to Th3 cells which are enhanced by TGF-β, IL-4 and IL-10. Thus, a polarized Th2 systemic immune response enhances the subsequent development of Th3 cells that are capable of producing TGF-β, inhibits Th1 cytokine expression and finally contributes to HTS formation (See Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Hypothetical diagram of the role of Th1/Th2/Th3 cells in stimulating bone marrow stem cells to healing wounds. (From Armour A, Scott PG, Tredget EE (2007) Cellular and molecular pathology of HTS: basis for treatment. Wound Repair Regen 15:S6-17; with permission)

Fibrocytes, alternative precursors of myofibroblasts, play a pivotal role in HTS formation

Fibrocytes originate from the bone marrow and constitute 0.1 % to 0.5 % of peripheral blood cells (Quan et al. 2004). Fibrocytes have been reported to express surface markers CD34, CD45, collagen (Bucala et al. 1994) and leukocyte specific protein-1 (LSP-1) (Wang et al. 2007b). Peripheral blood fibrocytes can rapidly enter the site of injury along with inflammatory cells and participate in many aspects of wound healing, including production of ECM, antigen presentation, cytokine production, angiogenesis and wound closure (Chesney et al. 1997; Abe et al. 2001; Metz 2003). TGF-β1 could induce the differentiation of fibrocytes into myofibroblasts through activating Smad2/3 and JNK MARK pathways (Hong et al. 2007) during wound healing (Mori et al. 2005).

A series of studies conducted by our group have established a role for fibrocytes in HTS formation. The peripheral blood of 18 burn patients was examined and the results showed increased fibrocytes compared to 12 controls (Yang et al. 2002). The number of fibrocytes was found higher in HTS than in mature scar tissue and a unique surface marker protein, identified as LSP-1, was found in fibrocytes and in lymphocytes, but was undetectable in fibroblasts, allowing identification of these cells by double staining with antibodies to type I collagen and LSP-1(Yang et al. 2005). LSP-1 is reported to be important in leukocyte chemotaxis. Excisional wounds in an LSP-1 deficient mouse model showed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds with higher fibrocyte infiltration as well as up-regulation of TGF-β1 (Wang et al. 2007a).

Chemokines contribute to HTS formation by recruiting monocytes into wound sites

Chemokines are small 8–10 kilodalon proteins that induce chemotaxis in responsive cells surrounding the site of injury. They can be divided into four types depending on the spacing and location two cysteine residues in the molecules and include CC, CXC, C and CX3C subfamilies (Fernandez and Lolis 2002).

SDF-1, also known as CXCL12, belongs to CXC group. SDF-1 is similarly expressed in humans, swine and rat skin and is produced by pericytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts (Mirshahi et al. 2000). CXCR4 is a CXC chemokine receptor and it exclusively binds to SDF-1, which is unique among receptors because most chemokines have more than one receptor and most receptors have more than one ligand (Choi and An 2011). SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway mediates the migration of hemotopoietic cells from fetal liver to bone marrow (Zou et al. 1998), and could also stimulate angiogenesis by recruiting progenitor cells (Nagasawa 2001). Early studies focused on the functions of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in the regulation of stem/progenitor cell trafficking, especially tumor cells metastasis and tumor vascularization (Balkwill 2004). However, recent studies have suggested that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling participates in the pathogenesis of lung injury and fibrosis (Xu et al. 2007). An experiment using skin from burn patients showed an increased expression of SDF-1 in human burn blister fluid and improved skin recovery after blocking the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway (Avniel et al. 2006). A more recent study from our research group showed up-regulated SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in burn patients with increased SDF-1 levels in HTS and serum. Our study showed that SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling was important in the pathogenesis of HTS by stimulating the migration of activated CD14+ CXCR4+ cells to migrate to the injured tissue. These migrating cells may differentiate into fibrocytes and myofibroblasts and contribute to the pathogenesis of HTS (Ding et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2007c).

Another chemokine linked to the formation of HTS is monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). It belongs to the CC chemokine subfamily and has two receptors, CCR2 and CCR4 (Craig and Loberg 2006). Being a major chemoattractant, it is secreted by macrophages, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. MCP-1 recruits monocytes and dendritic cells to the inflammatory sites (Hasegawa and Sato 2008; Xu et al. 1996). A previous study showed that MCP-1 could stimulate fibroblast collagen production in the lung through an up-regulation of endogenous TGF-β (Gharaee-Kermani et al. 1996). A later experiment investigated the role of MCP-1 in fibrosis using MCP-1 knockout mice. Results showed that fibrosis was diminished in MCP-1 knockout mice compared to the bleomycin-induced fibrosis control group (Ferreira et al. 2006). Enhanced release of MCP-1 by keloid CD14+ cells stimulated fibroblast proliferation through the protein kinase B (PKB) signaling pathway and might trigger keloid development (Liao et al. 2010). A study from our research group demonstrated a significant increase of MCP-1 expression in fibroblasts from HTS compared to normal fibroblasts further suggesting a dominant role for MCP-1 in fibrotic diseases (Wang et al. 2011b).

Antifibrotic molecules, decorin and IFN-α2b inhibit HTS formation by inhibiting TGF-β and regulating fibroblasts

Recently, more research focuses on SLRPs, a small component of ECM molecules, which contain several repeated leucine-rich regions and cysteine residues. The major SLRPs are decorin, biglycan, lumican, and fibromodulin (Sidgwick and Bayat 2012). The most common SLRPs studied is decorin that is abundantly expressed in the dermis and in connective tissue (Honardoust et al. 2011). As well, it appears to promote collagen fibrillogenesis, cell differentiation and inhibits the bioactivity of growth factors such as TGF-β (Schönherr and Hausser 2000). We have reported different levels of decorin in burn wounds with suppressed expression for the first 12 months, then significantly higher expression after one to two years, decreasing to resemble the expression seen in normal skin after 3 years (Sayani et al. 2000). Decorin is considered to be an inhibitor of TGF-β. Animal studies using bleomycin-injected mice treated with adenovirus vector-derived decorin showed that decorin significantly reduced the fibrosis caused by bleomycin by blocking the fibrotic effect of TGF-β (Kolb et al. 2001). Wang et al. previously reported that deep dermal fibroblasts might contribute to HTS formation because of a decrease in decorin production (Wang et al. 2008a). Recently, decorin was used to treat superficial and deep dermal fibroblasts where increased cell apoptosis was seen in superficial dermal fibroblasts compared to deep dermal fibroblasts, suggesting decorin-induced apoptosis might play an anti-fibrotic role (Honardous et al. 2012a, b). Further study is needed to clarify the interaction between SLRPs and TGF-β 1 in superficial and deep wounds to demonstrate how the decreased expression of decorin and TGF-β1 in deep dermal fibroblasts contributes to the formation of HTS (Honardous et al. 2012a).

IFN, known as a Th1 cytokine, could be divided into three subtypes, type 1 IFN (including IFN-α and IFN-β), type 2 IFN (IFN-γ) and type 3 IFN (IFN-λ) (Ladak and Tredget 2009). IFN-α is produced by leukocytes and fibroblasts, while IFN-γ is produced by T lymphocytes such as activated T cells (Sarkhosh et al. 2003). IFN-α and IFN-γ could decrease cell proliferation and collagen synthesis in normal and HTS fibroblasts in vitro (Tredget et al. 1997). IFN-α2b is an antiviral drug originally used for viral infections and some forms of cancer and has recently been shown to increase collagenase mRNA levels and activity and reduce the activity of TIMP-1 (Ghahary et al. 1995a), thereby decreasing HTS formation. Further studies were carried out in the authors’ laboratory focusing on IFN-α2b because of the antifibrotic effects it exhibited. IFN-α2b exposure to matched pairs of human HTS and normal fibroblasts could inhibit wound contraction by decreasing fibroblast-populated collagen lattices (Nedelec et al. 1995). Patients with severe HTS treated with IFN-α2b showed a significant improvement in scar quality and volume during the therapy with a significant decrease in serum TGF-β levels (Tredget et al. 1998). Treating HTS and normal fibroblasts with IFN-α2b or IFN-γ demonstrated that TGF-β protein production was antagonized in part by the down-regulation of TGF-β1 mRNA levels (Tredget et al. 2000). Additionally, IFN-α2b treatment decreased angiogenesis in HTS tissue (Wang et al. 2008a). In a double blind placebo controlled trial in 21 burn patients conducted by our group, the administration of IFN-α2b to burn patients down-regulated SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in HTS tissues limiting the formation of HTS (Ding et al. 2011), which supported the contention that IFN-α2b is an antifibrotic protein inhibiting HTS formation.

We have reviewed the important factors that impact HTS formation. Increasing evidence indicates that HTS develop after multifactoral interactions of TGF-β1, Th1/2/3 cytokines, decorin and MMPs acting in different phases of the wound healing process.

The treatment of HTS

Current treatment of HTS remains time-consuming, expensive and with few consistently successful approaches. One of the difficulties is that the outcome of HTS formation varies between patients, scar location and between conservative interventions. So it is extremely difficult for surgeons to predict which scars need surgical excision or which scars might resolve over time (Tredget et al. 1997). There are however a variety of therapeutic options available to treat HTS, including surgical excision and non-surgical treatment.

Surgical therapy for HTS

Surgical excision is common management when used in combination with steroids and/or silicone gel sheeting. However, surgical excision of HTS without adjuvant therapy is associated with a high rate of recurrence, ranging from 50 % to 80 % (Darzi et al. 1992). HTS resulting from excessive tension or wound complications can be treated effectively with surgery options including intramarginal excision, skin grafts, local flaps and free flaps combined with surgical taping and silicone gel sheeting (Mustoe et al. 2002). But these technique are not suitable for immature scar.

There are two major kind of lasers, ablative nonselective lasers such as CO2 laser and nonablative selective lasers such as pulse-dye laser. Ablative lasers might carry a higher risk while nonablative lasers have the advantage of improving scars without incision or wounding. The flash lamp-pumped pulsed dye laser is extensively used to refine scars by causing direct destruction of the blood vessels and an indirect effect on the surrounding collagen, which result in collagen modeling and wound contraction (Lee et al. 2005).

Non-surgical therapy for HTS

Non-surgical management of HTS includes the use of pressure garments, intralesional corticosteroid administration, silicone gel sheets and so on. Pressure garment are commonly used and are supplied by several companies based on individual patient measurements (Macintyre and Baird 2006). Pressure therapy should be applied 24 h a day until the scar is mature. The optimum pressure for effective treatment is still unknown, but the pressures applied should exceed capillary pressure and recommend that pressure be maintained between 24 and 30 mmHg (Mustoe et al. 2002). The possible mechanism of pressure garment may relate to reduced fibroblast proliferation, decreased collagen synthesis, increased myofibroblasts apoptosis (Armour et al. 2007; Anzarut et al. 2009).

Intralesional corticosteroid administration is also widely used to alleviate HTS. Triamcinolone acetonide is the most commonly used corticosteroid. The administration should be confined to the dermal region of the scar with 10 to 40 mg/ml at 2- to 6-weeks interval (Atiyeh 2007). Silicone gel is a cross-linked polymer of dimethylsiloxane, which has been used for treatment of immature scar. Applying silicone gel sheet topically is a noninvasive and relatively safe treatment since it may decrease the volume of HTS (Ahn et al. 1989). It has been shown that silicone gel sheets may accelerate scar maturation and improve pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, pain and itchiness associated with HTS (Momeni et al. 2009). Thus, prophylactic use of topical silicone gel following scar revision surgery may prevent the development of recurrent HTS (Gold et al. 2001).

Future perspective

Despite the complexity of HTS, significant accomplishments have been made to establish a number of wound healing and dermal fibrotic animal models. Recently the author’s laboratory has transplanted human skin onto the backs of nude mice creating a human HTS-like nude mouse model. An increase infiltration of fibrocytes and macrophages has been observed, which suggest that they may contribute to HTS development (Wang et al. 2011a). Meanwhile, more research findings have suggested a critical role of macrophages in fibrotic diseases (Lucas et al. 2010; Murray et al. 2011). Thus, our future perspective will be focusing on the roles of the macrophages and different types of macrophages in the the development of HTS using the nude mouse model, which will assist clinicians in the development of novel forms of treatment to prevent and treat HTS and other fibrotic disorders.

Abbreviations

- ALK 1

activin-receptor-like kinase 1

- ALK 5

activin-receptor-like kinase 5

- α-SMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- COL1

type I collagen

- COL1A2

collagen type I α2

- COL3

type III collagen

- COL4

type IV collagen

- Co-SMAD

common mediator Smad

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HTS

hypertrophic scar

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IL

interleukin

- IFN

interferon

- I-SMAD

inhibitory Smad

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LSP-1

leukocyte specific protein-1

- LTBP

latent TGF-β1 binding protein

- M6P/IGF II-R

Mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptors

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- PKB

protein kinase B

- R-Smad

receptor-regulated Smad

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- SIP1

Smad interacting protein 1

- SLRP

small leucine-rich proteoglycan

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TGF-βR

TGF-β receptor

- TIEG1

TGF-β inducible early gene 1

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Firefighters’ Burn Trust Fund of the University of Alberta.

References

- Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN (2001) Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol 15;166(12):7556–7562 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ahn ST, Monafo WW, Mustoe TA. Topical silicone gel: a new treatment for hypertrophic scars. Surgery. 1989;106(4):781–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Bahar M, Bauer B, Tredget EE, Ghahary A. Dermal fibroblasts from different layers of human skin are heterogeneous in expression of collagenase and types I and III procollagen mRNA. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(2):175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB (2003) Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci 15;116(Pt 2):217–224 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anzarut A, Olson J, Singh P, Rowe BH, Tredget EE. The effectiveness of pressure garment therapy for the prevention of abnormal scarring after burn injury: a meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Cellular and molecular pathology of HTS: basis for treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(Suppl 1):S6–S17. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft GS, Yang X, Glick AB, Weinstein M, Letterio JL, Mizel DE, Anzano M, Greenwell-Wild T, Wahl SM, Deng C, Roberts AB. Mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated wound healing and an impaired local inflammatory response. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(5):260–266. doi: 10.1038/12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh BS. Nonsurgical management of hypertrophic scars: evidence-based therapies, standard practices, and emerging methods. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31(5):468–492. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0253-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN. Keloid or hypertrophic scar: the controversy: review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54(6):676–680. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000164538.72375.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avniel S, Arik Z, Maly A, Sagie A, Basst HB, Yahana MD, Weiss ID, Pal B, Wald O, Ad-El D, Fujii N, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Jung S, Galun E, Gur E, Peled A. Involvement of the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway in the recovery of skin following burns. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(2):468–476. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer BS, Tredget EE, Marcoux Y, Scott PG, Ghahary A. Latent and active transforming growth factor beta1 released from genetically modified keratinocytes modulates extracellular matrix expression by dermal fibroblasts in a coculture system. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119(2):456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock O, Yu H, Zitron S, Bayat A, Ferguson MW, Mrowietz U. Studies of transforming growth factors beta 1–3 and their receptors I and II in fibroblast of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(3):216–220. doi: 10.1080/00015550410025453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombaro KM, Engrav LH, Carrougher GJ, Wiechman SA, Faucher L, Costa BA, Heimbach DM, Rivara FP, Honari S. What is the prevalence of hypertrophic scarring following burns? Burns. 2003;29(4):299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonniaud P, Kolb M, Galt T, Robertson J, Robbins C, Stampfli M, Lavery C, Margetts PJ, Roberts AB, Gauldie J. Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to TGF-beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):2099–2108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekelmann TJ, Limper AH, Colby TV, McDonald JA (1991) Transforming growth factor beta 1 is present at sites of extracellular matrix gene expression in human pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1;88(15):6642–6646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1(1):71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli C, Stella M, Magliacani G. Role of T-lymphocytes and cytokines in post-burn hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10(2):107–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253(1–2):269–285. doi: 10.1023/a:1026028303196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T, Ghahary A, Demare J, Yang L, Iwashina T, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Development, characterization, and wound healing of the keratin 14 promoted transforming growth factor-beta1 transgenic mouse. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10(3):177–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.11101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney J, Bacher M, Bender A, Bucala R (1997) The peripheral blood fibrocyte is a potent antigen-presenting cell capable of priming naive T cells in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 10;94(12):6307–6412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Choi WT, An J. Biology and clinical relevance of chemokines and chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in human diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236(6):637–647. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.010389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig MJ, Loberg RD. CCL2 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1) in cancer bone metastases. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(4):611–619. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutroneo KR. TGF-beta-induced fibrosis and SMAD signaling: oligo decoys as natural therapeutics for inhibition of tissue fibrosis and scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(Suppl 1):S54–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CM, Beanes SR, Lee H, Zhang X, Soo C, Ting K. Scarless fetal wounds are associated with an increased matrix metalloproteinase-to-tissue-derived inhibitor of metalloproteinase ratio. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(7):2273–2285. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000060102.57809.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzi MA, Chowdri NA, Kaul SK, Khan M. Evaluation of various methods of treating keloids and hypertrophic scars: a 10-year follow-up study. Br J Plast Surg. 1992;45(5):374–379. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(92)90008-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Mandal M, Chakraborti T, Mandal A, Chakraborti S. Structure and evolutionary aspects of matrix metalloproteinases: a brief overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253(1–2):31–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1026093016148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PA, Corless DJ, Aspinall R, Wastell C. Effect of CD4(+) and CD8(+) cell depletion on wound healing. Br J Surg. 2001;88(2):298–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice B, Garbi C, Santoriello M, Santillo A, Wilson RR. Differential apoptosis markers in human keloids and hypertrophic scars fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;327(1–2):191–201. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmoulière A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122(1):103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Hori K, Zhang R, Marcoux Y, Honardoust D, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and its receptor CXCR4 in the formation of postburn hypertrophic scar (HTS) Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(5):568–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet C, Brouty-Boyé D, Pottin-Clémenceau C, Canonica GW, Jasmin C, Azzarone B. Interleukin (IL) 4 and IL-13 act on human lung fibroblasts. Implication in asthma. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(10):2129–2139. doi: 10.1172/JCI741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkin CS, Pleat JM, Gillespie PH, Tyler MP, Roberts AH, McGrouther DA. Scarring occurs at a critical depth of skin injury: precise measurement in a graduated dermal scratch in human volunteers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1722–1732. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000258829.07399.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engrav LH, Garner WL, Tredget EE. Hypertrophic scar, wound contraction and hyper-hypopigmentation. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(4):593–597. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E318093E482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto H, Suga H, Aoi N, Kato H, Doi K, Kuno S, Tabata Y, Yoshimura K. Therapeutic potential of fibroblast growth factor-2 for hypertrophic scars: upregulation of MMP-1 and HGF expression. Lab Invest. 2012;92(2):214–223. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SR, Trojanowska M, Smith EA, Leroy EC. Differential responses of human papillary and reticular fibroblasts to growth factors. Am J Med Sci. 1993;305(4):203–207. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez EJ, Lolis E. Structure, function, and inhibition of chemokines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:469–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091901.115838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AM, Takagawa S, Fresco R, Zhu X, Varga J, DiPietro LA. Diminished induction of skin fibrosis in mice with MCP-1 deficiency. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(8):1900–1908. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Shen YJ, Nedelec B, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Interferons gamma and alpha-2b differentially regulate the expression of collagenase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 messenger RNA in human hypertrophic and normal dermal fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen. 1995;3(2):176–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1995.30209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Shen YJ, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Immunolocalization of TGF-beta 1 in human hypertrophic scar and normal dermal tissues. Cytokine. 1995;7(2):184–190. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Shen YJ, Nedelec B, Wang R, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Collagenase production is lower in post-burn hypertrophic scar fibroblasts than in normal fibroblasts and is reduced by insulin-like growth factor-1. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106(3):476–481. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12343658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Shen Q, Shen YJ, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Induction of transforming growth factor beta 1 by insulin-like growth factor-1 in dermal fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1998;174(3):301–309. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199803)174:3<301::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Tredget EE, Chang LJ, Scott PG, Shen Q. Genetically modified dermal keratinocytes express high levels of transforming growth factor-beta1. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(5):800–805. doi: 10.1038/jid.1998.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Tredget EE, Mi L, Yang L. Cellular response to latent TGF-beta1 is facilitated by insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptors on MS-9 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251(1):111–120. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Tredget EE, Shen Q, Kilani RT, Scott PG, Houle Y. Mannose-6-phosphate/IGF-II receptors mediate the effects of IGF-1-induced latent transforming growth factor beta 1 on expression of type I collagen and collagenase in dermal fibroblasts. Growth Factors. 2000;17(3):167–176. doi: 10.3109/08977190009001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Tredget EE, Ghahary A, Bahar MA, Telasky C. Cell proliferating effect of latent transforming growth factor-beta1 is cell membrane dependent. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10(5):328–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahary A, Marcoux Y, Karimi-Busheri F, Li Y, Tredget EE, Kilani RT, Lam E, Weinfeld M. Differentiated keratinocyte-releasable stratifin (14-3-3 sigma) stimulates MMP-1 expression in dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124(1):170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharaee-Kermani M, Denholm EM, Phan SH. Costimulation of fibroblast collagen and transforming growth factor beta1 gene expression by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 via specific receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(30):17779–17784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MH, Foster TD, Adair MA, Burlison K, Lewis T. Prevention of hypertrophic scars and keloids by the prophylactic use of topical silicone gel sheets following a surgical procedure in an office setting. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(7):641–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment and fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637–3647. doi: 10.2741/2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honardoust D, Varkey M, Hori K, Ding J, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, decorin and fibromodulin, are reduced in postburn hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(3):368–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honardoust D, Ding J, Varkey M, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE (2012a) Deep Dermal Fibroblasts Refractory to Migration and Decorin-Induced Apoptosis Contribute to Hypertrophic Scarring. J Burn Care Res 2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Honardoust D, Varkey M, Marcoux Y, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Reduced decorin, fibromodulin, and transforming growth factor-β3 in deep dermis leads to hypertrophic scarring. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(2):218–227. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182335980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KM, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Differentiation of human circulating fibrocytes as mediated by transforming growth factor-beta and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(31):22910–22920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori K, Ding J, Marcoux Y, Iwashina T, Sakurai H, Tredget EE. Impaired cutaneous wound healing in transforming growth factor-β inducible early gene1 knockout mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(2):166–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilani RT, Delehanty M, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Scott P, Tredget EE. Fluorescent-activated cell-sorting analysis of intracellular interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in fresh and frozen human peripheral blood T-helper cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13(4):441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BC, Kim HT, Park SH, Cha JS, Yufit T, Kim SJ, Falanga V. Fibroblasts from chronic wounds show altered TGF-beta-signaling and decreased TGF-beta Type II receptor expression. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(3):331–336. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass BR, Grobbelaar AO, Rolfe KJ. Transforming growth factor beta1 signalling, wound healing and repair: a multifunctional cytokine with clinical implications for wound repair, a delicate balance. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(999):9–14. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.069831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Galt T, Sime PJ, Xing Z, Schmidt M, Gauldie J. Transient transgene expression of decorin in the lung reduces the fibrotic response to bleomycin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 1):770–777. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2006084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp J, Preis E, Said H, Hafemann B, Wickert L, Gressner AM, Pallua N, Dooley S. Abrogation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling by SMAD7 inhibits collagen gel contraction of human dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(22):21570–21576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan P, Hori K, Ding J, Tredget EE. Scar and contracture: biological principles. Hand Clin. 2009;25(4):511–528. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladak A, Tredget EE. Pathophysiology and management of the burn scar. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(4):661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E, Tredget EE, Marcoux Y, Li Y, Ghahary A. Insulin suppresses collagenase stimulatory effect of stratifin in dermal fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;266(1–2):167–174. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049156.82563.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E, Kilani RT, Li Y, Tredget EE, Ghahary A. Stratifin-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 in fibroblast is mediated by c-fos and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(2):230–238. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KK, Mehrany K, Swanson NA. Surgical revision. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23(1):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EK, Lee YS, Han IO, Park SH (2007) Expression of Caveolin-1 reduces cellular responses to TGF-beta1 through down-regulating the expression of TGF-beta type II receptor gene in NIH3T3 fibroblast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 27;359(2):385–90. Epub 2007 May 25 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liao WT, Yu HS, Arbiser JL, Hong CH, Govindarajan B, Chai CY, Shan WJ, Lin YF, Chen GS, Lee CH. Enhanced MCP-1 release by keloid CD14+ cells augments fibroblast proliferation: role of MCP-1 and Akt pathway in keloids. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(8):e142–e150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtinghagen R, Michels D, Haberkorn CI, Arndt B, Bahr M, Flemming P, Manns MP, Boeker KH. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-7, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 are closely related to the fibroproliferative process in the liver during chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2001;34(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chua C, Wu X, Wang D, Ying D, Cui L, Cao Y. Inhibiting scar formation in rat wounds by adenovirus-mediated overexpression of truncated TGF-beta receptor II. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(3):860–870. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000153037.12900.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Saulis AS, Liu WR, Roy NK, Chao JD, Ledbetter S, Mustoe TA. The temporal effects of anti-TGF-beta1, 2, and 3 monoclonal antibody on wound healing and hypertrophic scar formation. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas T, Waisman A, Ranjan R, Roes J, Krieg T, Müller W, Roers A, Eming SA (2010) Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol 1;184(7):3964–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903356. Epub 2010 Feb 22 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Macintyre L, Baird M. Pressure garments for use in the treatment of hypertrophic scars–a review of the problems associated with their use. Burns. 2006;32(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JA, Gawronska-Kozak B. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) is upregulated during scarless wound healing in athymic nude mice. Matrix Biol. 2006;25(8):505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall S, Dallon J, Sherratt J, Maini P (2006) Fibroblast migration and collagen deposition during dermal wound healing: mathematical modelling and clinical implications. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci 15;364(1843):1385–1405 [DOI] [PubMed]

- McGee GS, Broadley KN, Buckley A, Aquino A, Woodward SC, Demetriou AA, Davidson JM. Recombinant transforming growth factor beta accelerates incisional wound healing. Curr Surg. 1989;46(2):103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz CN. Fibrocytes: a unique cell population implicated in wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(7):1342–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MC, Nanchahal J. Advances in the modulation of cutaneous wound healing and scarring. BioDrugs. 2005;19(6):363–381. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200519060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirshahi F, Pourtau J, Li H, Muraine M, Trochon V, Legrand E, Vannier J, Soria J, Vasse M, Soria C (2000) SDF-1 activity on microvascular endothelial cells: consequences on angiogenesis in in vitro and in vivo models. Thromb Res 15;99(6):587–594 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Momeni M, Hafezi F, Rahbar H, Karimi H. Effects of silicone gel on burn scars. Burns. 2009;35(1):70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monstrey S, Hoeksema H, Verbelen J, Pirayesh A, Blondeel P. Assessment of burn depth and burn wound healing potential. Burns. 2008;34(6):761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Pallone F, MacDonald TT. Smad7 in TGF-beta-mediated negative regulation of gut inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(10):513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori L, Bellini A, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Fibrocytes contribute to the myofibroblast population in wounded skin and originate from the bone marrow. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin V, Larochelle S, Langlois C, Thibault I, Lopez-Vallé CA, Roy M. Normal skin wound and hypertrophic scar myofibroblasts have differential responses to apoptotic inductors. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198(3):350–358. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Non-Smad TGF-beta signals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 16):3573–3584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, Argentieri RL, Peng X, Gulati M, Homer RJ, Russell T, van Rooijen N, Elias JA, Hogaboam CM, Herzog EL. TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by Serum amyloid P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43(1):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, Hobbs FD, Ramelet AA, Shakespeare PG, Stella M, Téot L, Wood FM, Ziegler UE. International Advisory Panel on Scar Management. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):560–571. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T. Role of chemokine SDF-1/PBSF and its receptor CXCR4 in blood vessel development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;947:112–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelec B, Shen YJ, Ghahary A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. The effect of interferon alpha 2b on the expression of cytoskeletal proteins in an in vitro model of wound contraction. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126(5):474–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelec B, Ghahary A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Control of wound contraction. Basic and clinical features. Hand Clin. 2000;16(2):289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelec B, Shankowsky H, Scott PG, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Myofibroblasts and apoptosis in human hypertrophic scars: the effect of interferon-alpha2b. Surgery. 2001;130(5):798–808. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan ST, Lederer JA, Horgan AF, Chin DH, Mannick JA, Rodrick ML. Major injury leads to predominance of the T helper-2 lymphocyte phenotype and diminished interleukin-12 production associated with decreased resistance to infection. Ann Surg. 1995;222(4):482–490. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199522240-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu J, Nakerakanti S, Smith E, ten Dijke P, Trojanowska M. Transforming growth factor-beta receptor type I-dependent fibrogenic gene program is mediated via activation of Smad1 and ERK1/2 pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(14):10405–10413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611742200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke JM, Sorg H (2012) Wound Repair and Regeneration. Eur Surg Res 11;49(1):35–43 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reynolds JJ. Collagenases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: a functional balance in tissue degradation. Oral Dis. 1996;2(1):70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1996.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, Smith JM, Roche NS, Wakefield LM, Heine UI, Liotta LA, Falanga V, Kehrl JH, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(12):4167–4171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Trovato MJ, You R, Lal BK, Fasehun F, Padberg FT, Jr, Hobson RW, 2nd, Durán WN, Pappas PJ. Role of matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(5):930–938. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.119503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkhosh K, Tredget EE, Karami A, Uludag H, Iwashina T, Kilani RT, Ghahary A. Immune cell proliferation is suppressed by the interferon-gamma-induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression of fibroblasts populated in collagen gel (FPCG) J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(1):206–217. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki G, Marcoux Y, Sarkhosh K, Tredget EE, Ghahary A. Interaction of keratinocytes and fibroblasts modulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases-2 and −9 and their inhibitors. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;269(1–2):209–216. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-3178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayani K, Dodd CM, Nedelec B, Shen YJ, Ghahary A, Tredget EE, Scott PG. Delayed appearance of decorin in healing burn scars. Histopathology. 2000;36(3):262–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr E, Hausser HJ. Extracellular matrix and cytokines: a functional unit. Dev Immunol. 2000;7(2–4):89–101. doi: 10.1155/2000/31748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott PG, Dodd CM, Tredget EE, Ghahary A, Rahemtulla F. Immunohistochemical localization of the proteoglycans decorin, biglycan and versican and transforming growth factor-beta in human post-burn hypertrophic and mature scars. Histopathology. 1995;26(5):423–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott PG, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Molecular and cellular aspects of fibrosis following thermal injury. Hand Clin. 2000;16(2):271–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralising antibody to TGF-beta 1,2 reduces cutaneous scarring in adult rodents. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 5):1137–1157. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.5.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralisation of TGF-beta 1 and TGF-beta 2 or exogenous addition of TGF-beta 3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 3):985–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi-wen X, Stanton LA, Kennedy L, Pala D, Chen Y, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, Carter DE, Bou-Gharios G, Stratton RJ, Pearson JD, Beier F, Lyons KM, Black CM, Abraham DJ, Leask A (2006) CCN2 is necessary for adhesive responses to transforming growth factor-beta1 in embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 21;281(16):10715–10726. Epub 2006 Feb 16 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sidgwick GP, Bayat A. Extracellular matrix molecules implicated in hypertrophic and keloid scarring. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):141–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon F, Bergeron D, Larochelle S, Lopez-Vallé CA, Genest H, Armour A, Moulin VJ. Enhanced secretion of TIMP-1 by human hypertrophic scar keratinocytes could contribute to fibrosis. Burns. 2012;38(3):421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell JM, Caplan AI. Fibroblast heterogeneity: more than skin deep. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 5):667–675. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamenkovic I. Extracellular matrix remodelling: the role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2003;200(4):448–464. doi: 10.1002/path.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa M, Anhuf D, Terstegen L, Gatsios P, Gressner AM, Dooley S. Participation of Smad2, Smad3, and Smad4 in transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta)-induced activation of Smad7. THE TGF-beta response element of the promoter requires functional Smad binding element and E-box sequences for transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(38):29308–29317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanriverdi-Akhisaroglu S, Menderes A, Oktay G. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and −9 activities in human keloids, hypertrophic and atrophic scars: a pilot study. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27(2):81–87. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredget EE. Pathophysiology and treatment of fibroproliferative disorders following thermal injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;888:165–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredget EE, Nedelec B, Scott PG, Ghahary A. Hypertrophic scars, keloids, and contractures. The cellular and molecular basis for therapy. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(3):701–730. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70576-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredget EE, Shankowsky HA, Pannu R, Nedelec B, Iwashina T, Ghahary A, Taerum TV, Scott PG. Transforming growth factor-beta in thermally injured patients with hypertrophic scars: effects of interferon alpha-2b. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(5):1317–1328. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredget EE, Wang R, Shen Q, Scott PG, Ghahary A. Transforming growth factor-beta mRNA and protein in hypertrophic scar tissues and fibroblasts: antagonism by IFN-alpha and IFN-gamma in vitro and in vivo. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20(2):143–151. doi: 10.1089/107999000312540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tredget EE, Yang L, Delehanty M, Shankowsky H, Scott PG. Polarized Th2 cytokine production in patients with hypertrophic scar following thermal injury. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26(3):179–189. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D, Noah EM, von Heimburg D, Pallua N (2003) TIMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, and PIIINP as serum markers for skin fibrosis in patients following severe burn trauma. Plast Reconstr Surg 1;111(4):1423–1431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vaalamo M, Leivo T, Saarialho-Kere U. Differential expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, -2, -3, and −4) in normal and aberrant wound healing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(7):795–802. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Ghahary A, Shen YJ, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Human dermal fibroblasts produce nitric oxide and express both constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase isoforms. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106(3):419–427. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12343428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Ghahary A, Shen Q, Scott PG, Roy K, Tredget EE. Hypertrophic scar tissues and fibroblasts produce more transforming growth factor-beta1 mRNA and protein than normal skin and cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(2):128–137. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Hao J, Jones SC, Yee MS, Roth JC, Dixon IM. Decreased Smad 7 expression contributes to cardiac fibrosis in the infarcted rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282(5):H1685–H1696. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00266.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiao H, Stewart TL, Lyons MV, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Accelerated wound healing in leukocyte-specific, protein 1-deficient mouse is associated with increased infiltration of leukocytes and fibrocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(6):1554–1563. doi: 10.1189/0507306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JF, Jiao H, Stewart TL, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Fibrocytes from burn patients regulate the activities of fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(1):113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiao H, Stewart TL, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Increased TGF-beta-producing CD4+ T lymphocytes in postburn patients and their potential interaction with dermal fibroblasts in hypertrophic scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(4):530–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen H, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Improved scar in postburn patients following interferon-alpha2b treatment is associated with decreased angiogenesis mediated by vascular endothelial cell growth factor. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28(7):423–434. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dodd C, Shankowsky HA, Scott PG, Tredget EE, Wound Healing Research Group Deep dermal fibroblasts contribute to hypertrophic scarring. Lab Invest. 2008;88(12):1278–1290. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ding J, Jiao H, Honardoust D, Momtazi M, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Human hypertrophic scar-like nude mouse model: characterization of the molecular and cellular biology of the scar process. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(2):274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hori K, Ding J, Huang Y, Kwan P, Ladak A, Tredget EE. Toll-like receptors expressed by dermal fibroblasts contribute to hypertrophic scarring. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1265–1273. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA. Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(8):583–594. doi: 10.1038/nri1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie JL, Bian HN, Qi SH, Chen HD, Li HD, Xu YB, Li TZ, Liu XS, Liang HZ, Xin BR, Huan Y. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) alleviates the scar of the rabbit ear model in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(4):576–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LL, Warren MK, Rose WL, Gong W, Wang JM. Human recombinant monocyte chemotactic protein and other C-C chemokines bind and induce directional migration of dendritic cells in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60(3):365–371. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SW, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, Holmes A, Pearson JD, Dashwood MR, Bou-Gharios G, Denton CP, du Bois RM, Black CM, Leask A, Abraham DJ (2004) Endothelin-1 induces expression of matrix-associated genes in lung fibroblasts through MEK/ERK. J Biol Chem 28;279(22):23098–23103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu J, Mora A, Shim H, Stecenko A, Brigham KL, Rojas M. Role of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in the pathogenesis of lung injury and fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37(3):291–299. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0187OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Tredget EE, Ghahary A. Activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta1 is induced by mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(6):538–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Chan T, Demare J, Iwashina T, Ghahary A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Healing of burn wounds in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor-beta 1 in the epidermis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):2147–2157. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Scott PG, Giuffre J, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Peripheral blood fibrocytes from burn patients: identification and quantification of fibrocytes in adherent cells cultured from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Lab Invest. 2002;82(9):1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000027841.50269.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Scott PG, Dodd C, Medina A, Jiao H, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. Identification of fibrocytes in postburn hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13(4):398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Varga J (2001) Transforming growth factor-beta repression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in dermal fibroblasts involves Smad3. J Biol Chem 19;276(42):38502–38510. Epub 2001 Aug 13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang GY, He B, Liao T, Luan Q, Tao C, Nie CL, Albers AE, Zheng X, Xie XG, Gao WY. Caveolin 1 inhibits transforming growth factor-β1 activity via inhibition of Smad signaling by hypertrophic scar derived fibroblasts in vitro. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;62(2):128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZF, Zhang YG, Hu DH, Shi JH, Liu JQ, Zhao ZT, Wang HT, Bai XZ, Cai WX, Zhu HY, Tang CW. Smad interacting protein 1 as a regulator of skin fibrosis in pathological scars. Burns. 2011;37(4):665–672. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393(6685):595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]