Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the efficiency of intratympanic dexamethasone (ITD) injections as a new treatment modality in otitis media with effusion resistant to conventional therapy. We planned a nonrandomized prospective study to determine the safety and effectiveness of the direct administration of dexamethasone into middle ear cavity with chronic eustachian tube dysfunction. This study was applied on 75 ears of 64 patients aged from 12 to 60 years. ITD received 47 ears of 41 patients who had previously been treated by medical or surgical therapy middle ear effusion without resolution classified as study group. They were taken conventional medical therapy again 28 ears of 23 patients classified as a control group. ITDs were administered 0.5 ml/4 mg per mm directly in antero-superior quadrant of tympanic membrane. These injections were repeated once a week for 4 weeks. Results were evaluated by using audiometric and tympanometric measurements 1 and 3 months after the treatments. Audiometric measurement shows that 9.91 dB improvement in the mean air–bone gap 15.17 dB in air conduction (AC) pure-tone averages (PTA) and 5.25 dB bone conduction (BC) PTA. But the control group data showed only 2 dB improvement in the mean air–bone gap, 3 dB AC–PTA and 1.36 dB BC–PTA. Tympanometric improvement was found. In 28 ears of patients (59.6%) like type B or C converted to type A in study group without complication but only in three ears (10.7%) of control group. ITD administration to the middle ear is safe and effective for the treatment of otitis media with effusion or chronic eustachian tube dysfunction. No complications like tympanic membrane perforation and/or sensorineural hearing loss have occurred.

Keywords: Intratympanic dexamethasone, Otitis media with effusion, Resistant to conventional therapy, Hearing loses

Introduction

Otitis media with effusion (OME) in all its manifestations is a worldwide major health problem for both of children and adults who have a lifelong history of eustachian tube dysfunction [1]. It may have a significant negative impact on the patients’ quality of life and functional health status [2]. Chronic eustachian tube dysfunction is frequently encountered by otolaryngologists chronic OME is defined as middle ear effusion in one or both ears for 6 weeks to 6 months [2]. OME or eustachian tube dysfunction can result in negative middle ear pressure and precipitate associated signs and symptoms. These signs and symptoms include conductive hearing loss, tinnitus, otalgia, vertigo, permanent changes of tympanic membrane or atelectasis, cholesteatoma formation, and recurrent otitis media [3–6]. Several aetiological factors are taken into consideration in the progression of the illness. The middle ear tends to loose gas by diffusion into the surrounding mucosal circulation. It is characterised by the presence of fluid in the tympanic cavity and caused by pathological changes taking place in the mucous membrane of the middle ear. The causes of eustachian tube obstruction can vary, but the principal pathways involve mucosal oedema, degeneration and hypertrophy, which can be precipitated by allergic and reactive diseases [6, 7]. However many cellular and molecular mechanisms take place in aetio-pathogenesis as the basis of the immunological and inflammatory response in this disease [8]. The changes that occur in the middle ear mucosa are thought to be treated by steroids. This condition can be very difficult to treat, particularly in adults because, the treatment options still remain limited. Commonly used antibiotics have had limited impact in treating this condition [9] because about 40–60% of middle ear effusions were considered to be sterile in chronic OME when analyzed by bacterial culture [10, 11].

Currently, middle ear aeration via tympanotomy and tube insertion has been the choice of management for chronic effusions that do not respond to medical therapy. However, no method has been proven to be effective that involves treating eustachian tube pathology directly when conventional therapy fails. Several techniques have been proposed over the past years [7]. For example direct application of steroid into middle ear mucosa through tympanostomy tube or intratympanic injections of dexamethasone (ITD) were also found more effective in the reduction of granulation tissue than antibiotic therapy alone [12, 13].

We have developed a technique for treatment of chronic eustachian tube dysfunction that involves a transtympanic approach to the eustachian tube as a direct application of dexamethasone via 28 gauge needle through antero-superior quadrant of tympanic membranes. This method is aimed to determine the efficiency of ITD as a treatment modality in patients whom are resistant to standard therapy for OME. We propose that direct steroid application may serve to reduce mucosal hypertrophy and improve eustachian tube function.

Patients and Methods

We planned a nonrandomized controlled prospective clinical trial. This was conducted on 64 patients presenting with OME between January 2007 and December 2009. This study was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Experiments of the Current Haydarpaşa Numune Training and Research Hospital with protocol number (13/2009). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Statistically, there were no significant differences related to age, gender, disease suffering period, history of tube insertion, this was very important, hence the control and study groups were chosen amongst the patients who had the same clinical criteria.

All patients that were chosen for this study had complaint from either chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction or middle ear effusion, in one or both ears for 6 months, which could not be solved by classic treatments. Therefore, these patients were offered to have treatment with ITD.

These patients met four selection criteria for study group:

Their symptoms were consistent with eustachian tube dysfunction (e.g., hearing loss and aural fullness).

They had previously received either medical therapy or insertion of ventilation tubes but their ear problems couldn’t have resolved or recurred. They had shown middle ear pressure disturbance at least Type C tympanogram after conventional treatments before we offered treatment with the ITD.

Findings of tympanometer or clinical examinations suggested that their middle ear pressures were abnormal without adhesive otitis media.

Patients were at least 12 years old for application of ITD easily. The control group was chosen from these patients who had same criteria and refused ITD application. 75 ears of 64 patients who were between 12 and 60 years old (mean age 35.2 ± 1) were chosen according to these criteria. They had type B (n = 49) or C (n = 26) tympanograms and mean hearing levels (0.5 kHz + 1 kHz + 2 kHz + 4 kHz/4) of more than 20 dB. Nasopharyngeal and nasal examinations were performed on all patients to rule out an obstructing mass and chronic sinusitis. The treatments of ITD were started with the patients who had received and failed conservative treatment at least 6 months later. No one has preferred ventilation tube reinsertion. The procedure was performed at supine position under a microscope. Topical anaesthesia was achieved with lidocaine (10 mg/dose pump spray). An antero-superior quadrant puncture was made for perfusion by using a 28-gauge needle and a 1 ml syringe without the aspiration of the middle ear fluid. Approximately 0.5 ml of dexamethasone (4 mg/ml) was instilled through this site. The patients were instructed to avoid swallowing or moving in the supine position with the head tilted 45° to the healthy side for 15 min. ITD injections were repeated once a week for 5 weeks. The control group (28 ears of 23 patients) were given oral antibiotics (containing amoxicillin and clavulanic acid), local and systemic decongestant (xylomethazoline-HCl as nasal spray and pseudoephedrine-HCl t.i.d-per oral) treatment for 4 weeks. Pure tone audiometer and tympanogram were performed just before applications of ITD and conventional treatment. Finally pure tone audiometer and tympanogram were taken 1 and 3 months later from last injection and medical treatments. There were no signs of perforation and complications in all patients. Every patient has been treated and observed individually at least for 3 months in this study.

Statistical Analysis

All analysis was done by using statistical software in SPSS 11.5 program. Central and prevalence values, frequency tables, Chi-square (χ2) tests were used in analysis and evaluation. T test and Pearson’s correlation test were used in paired and independent groups. Independent t tests or Pearson’s χ2 tests were used to assess group differences in for applicability of data’s in normal distributions choose of the importance test in this study. Data variables were tested by both histogram and one sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The rank correlation coefficients served to evaluate to show applicability in normal distributions. Parametric importance tests were used for this reason. χ2 tests were used to assess group differences in results of improvement in tympanoaudiometric. P-values below 0.05 or 95% were regarded as significant.

Results

Air conduction (AC) and bone conduction (BC)—pure-tone average (PTA) were measured pre treatment, post treatment, and during follows ups as shown in Table 1. We list the means for both the four-frequency and the data at each individual frequency of PTA because of the variability in the air–bone gap across frequencies in ITD received group. Statistically, no differences has been seen in these two groups when evaluated in gender with χ2 test (P = 0.318), ages (P = 0.471) and tympanometry findings (P = 0.256) with t test.

Table 1.

Improvement of mean hearing levels in study and control groups of patients with OME (independent sample t test)

| Group | Mean | Std. deviation | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC first (dB) | Study | 40.81 | 14.525 | 1.285 | 0.203 |

| Control | 36.18 | 16.002 | |||

| AC last (dB) | Study | 25.64 | 14.399 | 2.021 | 0.047 |

| Control | 33.18 | 17.520 | |||

| BC first (dB) | Study | 14.70 | 8.968 | 1.888 | 0.063 |

| Control | 10.57 | 9.492 | |||

| BC last (dB) | Study | 9.45 | 8.056 | 0.112 | 0.911 |

| Control | 9.21 | 9.746 | |||

| GAP first (dB) | Study | 26.06 | 8.773 | 0.046 | 0.963 |

| Control | 25.96 | 9.481 | |||

| GAP last (dB) | Study | 16.15 | 9.139 | 3.403 | 0.001 |

| Control | 23.96 | 10.390 | |||

| Tymp first | Study | 2.70 | 0.462 | 1.145 | 0.256 |

| Control | 2.57 | 0.504 | |||

| Tymp last | Study | 1.79 | 0.806 | 3.792 | 0.000 |

| Control | 2.46 | 0.637 |

Values have showed differences with regards to groups in statically (P < 0.05). According to last AC was 33.18 dB in control group while it was 25.6 dB in the study group. Last GAP was 23.96 dB in control group while it was 16.15 dB in study group. Last tympanometry value was 2.46 in control group while it was 1.79 in the study group. The important views of points are that it was found marked differences between two groups, the value of study group lower than control group at last measurements. These results can give a positive outlook about effectiveness of ITD treatment

AC Air conduction of hearing, BC bone conduction of hearing, GAP air–bone hearing gap, dB decibel

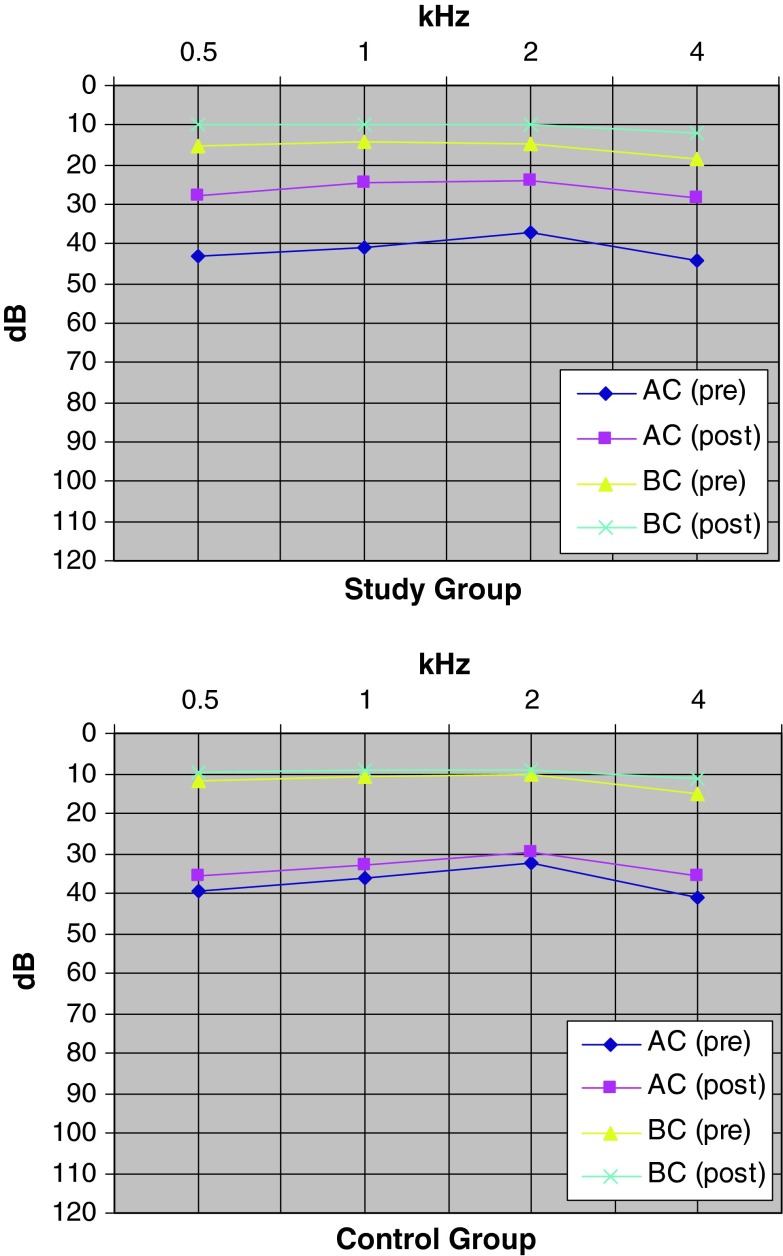

The mean AC–PTA improved from 40.8 to 25.6 dB, BC–PTA from 14.7 to 9.5 dB, air–bone gap from 26.1 to 16.2 dB 1 month after the treatment in ITD received group. The mean AC–PTA improved from 36.2 to 33.2 dB, BC–PTA from 10.6 to 9.2 dB, air–bone gap from 25.9 to 23.9 dB after the treatment in control group. These changes are demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mean pure tone audiometric changes of study and control groups before and after treatments. AC and BC pre and posttreatment changes were significant in statically in two groups (P < 0.05). The study group is shown more improvement in hearing levels than control group in AC. Pre before treatment, Post after treatment

Pre and post treatment mean AC and BC PTA thresholds, air–bone gap values of study and control groups were compared and statistically significant differences were found with paired sample t test (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

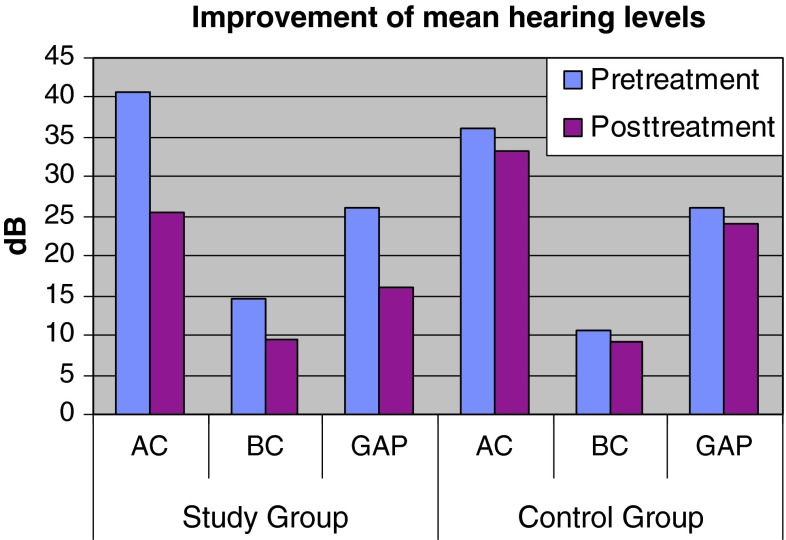

These two groups were compared in PTA and air–bone gap improvement degrees. The ITD received group showed better results when compared to the control group statistically with independent sample t test for PTA (P = 0.047) and air–bone gaps (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Fig. 2.

It is shown the improvement of mean hearing levels in study and control groups of patients with OME in histogram

Table 2.

The comparisons of first and last of mean AC, BC, GAP and tympanogram measurement inside of groups (Paired sample t test)

| Group | Mean | Std. deviation | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | ||||

| AC first (dB) | 40.81 | 14.525 | 9.658 | 0.000 |

| AC last (dB) | 25.64 | 14.399 | ||

| BC first (dB) | 14.70 | 8.968 | 6.320 | 0.000 |

| BC last (dB) | 9.45 | 8.056 | ||

| GAP first (dB) | 26.06 | 8.773 | 6.873 | 0.000 |

| GAP last (dB) | 16.15 | 9.139 | ||

| Tymp first | 2.70 | 0.462 | 7.332 | 0.000 |

| Tymp last | 1.79 | 0.806 | ||

| Control | ||||

| AC first (dB) | 36.18 | 16.002 | 4.177 | 0.000 |

| AC last (dB) | 33.18 | 17.520 | ||

| BC first (dB) | 10.57 | 9.492 | 3.293 | 0.003 |

| BC last (dB) | 9.21 | 9.746 | ||

| GAP first (dB) | 25.96 | 9.481 | 2.440 | 0.022 |

| GAP last (dB) | 23.96 | 10.390 | ||

| Tymp first | 2.57 | 0.504 | 1.800 | 0.083 |

| Tymp last | 2.46 | 0.637 | ||

While the first and last measurement of AC, BC, and GAP has shown differences. The first and last measurement of tympanogram has shown improvement in study group but not in control group. The last values were found lower than the first values in all of these changes

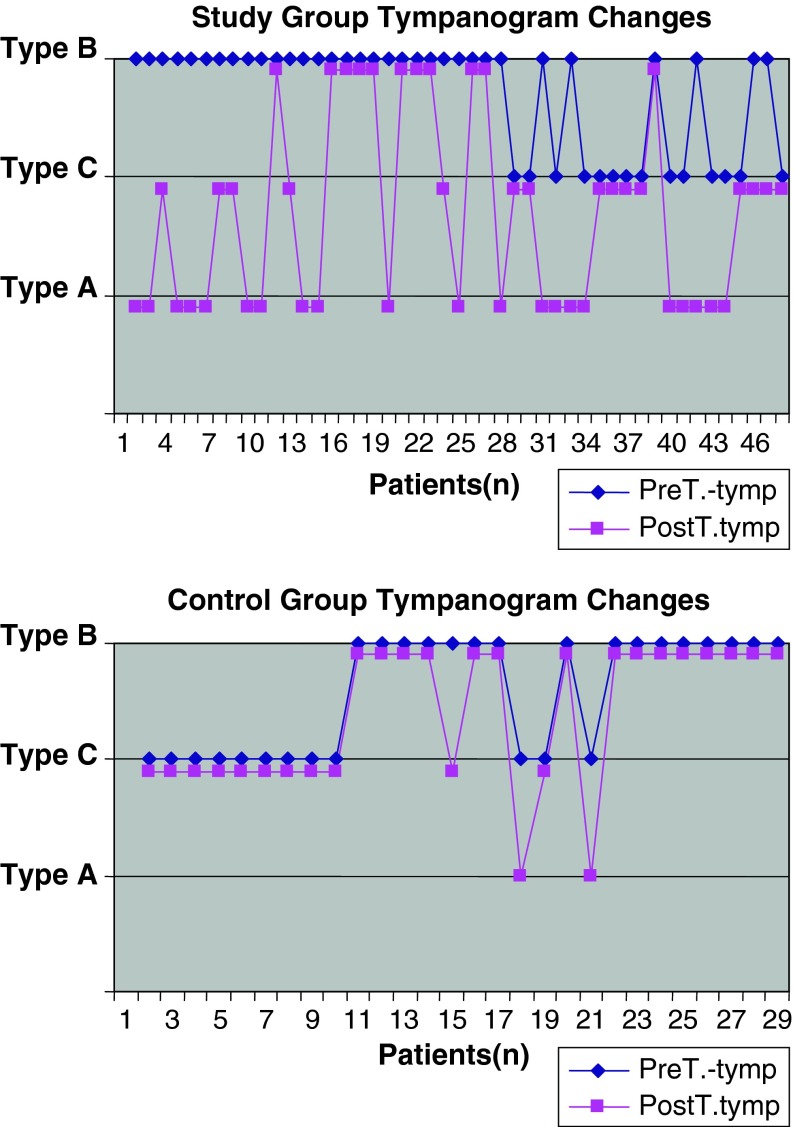

When tympanometric results were evaluated, 15 of 31 ears have improved from type B to type A, seven ears have improved from type B tympanograms to type C. nine ears with type B tympanograms showed no improvement. Six of 13 ears have improved from type C tympanograms to type A after treatment with ITD.

Only 2 of 12 ears have improved from type C tympanograms to type A and one of 16 ears have improved from type B tympanograms to type C. In control group, none of the ears with type B tympanograms have improved to type A after treatment. These changes are demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Improvement rates of the middle ears compliance of the patients. The tympanogram changes of patients after treatments in study and control groups. PreT before treatment, PostT after treatment

The percentages of improvement in tympanometric results were 59.6% (28/47) in study group and 10.7% (3/28) in the control group. These data clearly show that the improvement was statistically significantly higher in the study group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tympanogram improvement group * cross tabulation

| Groups | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Control | ||

| Tympanogram improvement | |||

| Positive | |||

| Count | 28 | 3 | 31 |

| % within group | 59.6 | 10.7 | 41.3 |

| Negative | |||

| Count | 19 | 25 | 44 |

| % within group | 40.4 | 89.3 | 58.7 |

| Total | |||

| Count | 47 | 28 | 75 |

| % within group | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| The results of importance test; P = 0.000 | |||

The improvement of tympanogram showed marked differences between two groups in statically (P < 0.05). It was found 10.7% in control group while it was 59.6% in study group

No significant differences were found in tympanometric improvement between ITD received and control group according to age and gender (P > 0.05).

All injections were applied easily and well tolerated by patients. No persistent tympanic membrane perforation and complications has occurred.

Discussion

There are lots of treatment modalities for resolution of OME where several aetiological factors are taken in consideration in pathogenesis. Persistent bacterial infection and associated chronic inflammation, causes Eustachian tube dysfunction, which itself is an important factor in leading to chronic OME. But 40–60% ears with OME were found with infectious agent [10, 11]. This finding leads us to think the role of anti inflammatory agents as a treatment method, especially steroids in treatment. Prescribing antibiotics, contributes to the growing problem of bacterial resistance. The optimal treatment strategy remains controversial and there is wide international variability in clinical practice [14]. OME treatment depends on multiple patient and disease specific factors. Middle ear aeration via tympanotomy and tube insertion has been the option of management for chronic effusions that do not respond to medical therapy [5]. The patients can benefit from surgical therapy but other factors can contribute to a more positive outcome [15]. However, treatment options still remain limited. Complications of long-term ventilation tube placement include otorrhea, persistent tympanic membrane perforations, and the inconvenience of adhering to dry-ear precautions. Unfortunately, the underlying patho-physiology usually leads to a recurrence of symptoms when the tube is removed and the tympanic membrane is allowed to heal [16–18]. Difficulties in application and complications of ventilation tubes made us to seek new, easy and effective treatment modality as ITD. Due to the factors listed, we have used ITD in this study. No complications have been reported with ITD application.

The effects of steroids and non-steroid anti inflamatuar were performed for many years as the treatment of the inflammatory middle ear disease. The ability of steroids to inhibit inflammation and reduce oedema has led to their use in the treatment of chronic OME.

Topical steroids have been shown to shorten the duration of acute OME, and oral prednisone has been shown to be effective in treating acute OME, although the degree of its long-term efficacy is unclear [14]. Silverstein et al. administrated dexamethasone to the eustachian tube by placing a micro-wick directly in the eustachian tube orifice through a pressure-equalization tube and they suggested that this method is safe and effective for the treatment of chronic OME. The incidence of persistent perforations found to be relatively low [7]. Dexamethasone and fosfomycin were performed via iontophoresis in one study. Improvement has been seen where type B tympanogram was converted to type A and converted to type C. Tympanometric results were found in 63.6% of study group patients and only in 37.1% of control group [19]. Tympanometric results were also significantly good in ITD received group (59.6%) as compared to the control group (10.7%) in our study (P < 0.05).

A different experimental study on an animal model reported that transtympanic steroid injections reduced lipopolysaccharide which induces middle ear effusion. They have also suggested that their results support to the current use of anti-inflammatory ototopical in the treatment of inflammatory middle ear disease such as corticosteroids, avoiding systemic side effects [13, 20]. It has also shown that combination therapy including dexamethasone has been to be more effective than antibiotic alone in the treatment of acute otitis media and otorrhea through a patent tympanostomy tube. The addition of dexamethasone is also more effective in the reduction of granulation tissue than antibiotic therapy alone [12, 15, 21]. In this study, we have found that ITD is also more effective than conventional therapy in the reduction of hearing loses and middle ear pressure in this study.

All of these studies have shown that there are more advantages of directed ototopical steroid therapy over systemic therapy. Topical medications often have limited systemic effects due to their limited systemic uptake. Its delivery may be further beneficial by altering pH and/or other factors in the local milieu. It may be less expensive as compared to systemic medications [13]. Hospitalization for insertion of ventilation tubes is the most common paediatric surgical procedure in many industrialized countries [22]. The total annual cost of treating children younger than 5 years for OME is more than $5 billion annually in the United States [23]. Cost of ITD treatments were lesser than conventional treatment due to the hospitalisation of the patients.

Many studies show that, patients with OME are followed up from 2 to 12 months using a typanometer after the treatment with conventional therapy [23–28]. In this study, we have followed up our cases using a typanometer but, 1 and 3 months after the medical treatment and ITD processes. We have chosen these time intervals to check our patients since these are the times that medical treatment effect is at its maximum; therefore, equal treatment time could be evaluated.

All cases of this study, previously received myringotomy, ventilation tube insertion and/or medical therapy at least once. 1 or 2 days after the application, tympanic membrane repairs the obstructed area itself. After 3 months, middle ear fluids couldn’t aspirate and discharge directly via this point hence we have used 28 gauge needles to achieve this. If any additive effect would come across from this application, we think it would be useful and not harmful.

We have aimed and found an easy and direct application of drugs like dexamethasone to the middle ear. None of the middle ear fluid was aspirated since it wasn’t required which was achievable by 28 gauge needle. The hearing improvements on PTA and tympanometric results were statistically significant in this study. We have presented the results of a new technique that is aimed at reducing mucosal oedema in the Eustachian tube and restoring tubal patency. The intratympanic steroid injection is a simple drug delivery system that can specifically target various structures in the middle ear. ITD injection appears to be well tolerated, as no adverse effects were seen. No persistent perforation of tympanic membrane had been seen. This procedure obviates the need for placing a ventilation tube in 59.6% of affected patients.

Considering that the patients enrolled in our study all had chronic, recurrent disease, the positive trend in hearing ability, the improvement reflected in tympanometry, and the alleviation of aural symptoms suggests that this is an effective treatment. Long-term studies to confirm our findings are under way.

Conclusion

The causes of OME and eustachian tube dysfunction are multi factorial; these include mucosal oedema, muscular dysfunction, cartilage collapse, and obstruction by structures in the nasopharynx. As improvements continue in diagnostic techniques for identifying the precise underlying patho-physiology in each individual case, patient selection for this treatment will become more refined.

This problem remains a common and potentially serious condition for which few treatment options exist. We have presented the results of a new technique that is aimed at reducing mucosal oedema in middle ear and restoring tubal patency. ITD procedure appears to be well tolerated, easily applicable as fairly effective for improvement hearing loses, shown no side effects in OME which resisted to conventional treatment.

References

- 1.Coates H, Thornton R, Langlands J, Filion P, Keil AD, Vijayasekaran S, Richmond P. The role of chronic infection in children with otitis media with effusion: evidence for intracellular persistence of bacteria. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(6):778–781. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer CN, Maille’ AR, Rovers MM, Grobbe DE, Sanders EA, Schilder AG. Health-related quality of life in children with otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bluestone CD, Doyle WJ. Anatomy and physiology of eustachian tube and middle ear related to otitis media. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;81(5 Pt 2):997–1003. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantekin EI, Bluestone CD, Parkin LP. Eustachian tube ventilatory function in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85(2 Suppl 25 Pt 2):171–177. doi: 10.1177/00034894760850S233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sade J, Ar A. Middle ear and auditory tube: middle ear clearance, gas exchange, and pressure regulation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;l16:499–524. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tos M. The intraluminal obstructive pathogenic concept of eustachian tube in secretory otitis media. In: Sade J, editor. Basic aspects of the eustachian tube and middle ear diseases. Amsterdam: Kugler and Ghedini; 1991. pp. 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein H, Light JP, Jackson LE, Rosenberg SI, Thompson JH., Jr Direct application of dexamethasone for the treatment of chronic eustachian tube dysfunction. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82(1):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skotnicka B, Hassmann E. Proinflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines in the middle ear effusions. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergie N, Bayston R, Pearson JP, Birchall JP. Is otitis media with effusion a biofilm infection? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29(1):38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park CW, Han JH, Jeong JH, et al. Detection rates of bacteria in chronic otitis media with effusion in children. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19(5):735–738. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rayner MG, Zhang Y, Gorry MC, et al. Evidence of bacterial metabolic activity in culture-negative otitis media with effusion. JAMA. 1998;279(4):296–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roland PS, Dohar JE, Lanier BJ, et al. Topical ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone otic suspension is superior to ofloxacin otic solution in the treatment of granulation tissue in children with acute otitis media with otorrhea through tympanostomy tubes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler JL, Wall M, Labadie RF. Effects of ototopic steroid and NSAIDS in clearing middle ear effusion in an animal model. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(4):585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.06.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler CC, van der Voort JH. Steroids for otitis media with effusion. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:641–647. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datema FR, Vemer-van den Hoek JG, Wieringa MH, Mulder PM, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Blom HM. A visual analog scale can assess the effect of surgical treatment in children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(4):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuknecht HF, Zaytoun GM, Moon CN., Jr Adult-onset fluid in the tympanomastoid compartment. Diagnosis and management. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:759–765. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790600003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamp CB., Jr Chronic secretory otitis media: etiologic factors and pathologic mechanisms. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:276–291. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paksoy M, Tezer I, Çelebi Ö, Şanlı A. Gold-plated and fluoroplastic ventilation tubes in the treatment of otitis media with effusion. KBB Klinikleri. 2006;8(1–3):11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato H, Takahashi H, Honjo I. Transtympanic iontophoresis of dexamethasone and fosfomycin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:531–533. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860170061019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florea A, Zwart JE, Lee CW, et al. Effect of topical dexamethasone versus rimexolone on middle ear inflammation in experimental otitis media with effusion. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:910–915. doi: 10.1080/00016480600606699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roland PS, Anon JB, Moe RD, et al. Topical ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone is superior to ciprofloxacin alone in paediatric patients with acute otitis media and otorrhea through tympanostomy tubes. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2116–2122. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haggard M, Hughes E (1991) Screening children’s hearing: a review of the literature and the implications for otitis media. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

- 23.Gates GA. Cost effectiveness considerations in otitis media treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:525–530. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van heerbeek N, Ingels KJ, Snik AF, Zielhuis GA. Eustachian tube function in children after insertion of ventilation tubes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110(12):1141–1146. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rovers MM, Straatman H, Ingels K, Van der wilt GI, Van den broek P, zielhuis GA. The effect of short-term ventilation tubes versus watchful waiting on hearing in young children with persistent otitis media with effusion: a randomized trial. Ear Hear. 2001;22(3):191–199. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunne M, Falk B, Hellström S, Magnuson B. Variability of eustachian tube function in children with secretory otitis media. Evaluations at tube insertion and at follow-up. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;52(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandel EM, Rockette HE, Bluestone CD, Paradise JL, Nozza RJ. Myringotomy with and without tympanostomy tubes for chronic otitis media with effusion. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115(10):1217–1224. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860340071020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prokopakis EP, Lachanas VA, Christodoulou PN, Velegrakis GA, Helidonis ES. Laser-assisted tympanostomy in pediatric patients with serous otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(4):601–604. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]