Abstract

Background

Failure after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may be related to emerging technologies, surgical techniques, and changing patient demographics. Over the past decade, TKA use in Korea has increased substantially, and demographic trends have diverged from those of Western countries, but failure mechanisms in Korea have not been well studied.

Questions/purposes

We determined the causes of failure after TKA, the risk factors for failure, and the trends in revision TKAs in Korea over the last 5 years.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 634 revision TKAs and 20,234 primary TKAs performed at 19 institutes affiliated with the Kleos Korea Research Group from 2008 to 2012. We recorded the causes of failure after TKA using 11 complications from the standardized complication list of The Knee Society, patient demographics, information on index and revision of TKAs, and indications for index TKA. The influences of patient demographics and indications for index TKA on the risk of TKA failure were evaluated using multivariate regression analysis. The trends in revision procedures and demographic features of the patients undergoing revision TKA over the last 5 years were assessed.

Results

The most common cumulative cause of TKA failure was infection (38%) followed by loosening (33%), wear (13%), instability (7%), and stiffness (3%). However, the incidence of infections has declined over the past 5 years, whereas that of loosening has increased and exceeds that of infection in the more recent 3 years. Young age (odds ratio [OR] per 10 years of age increase, 0.41; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37–0.49) and male sex (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.42–2.49) were associated with an increased risk of failure. The percentage of revision TKAs in all primary and revision TKAs remained at approximately 3%, but the annual numbers of revision TKAs in the more recent 3 years increased from that of 2008 by more than 23%.

Conclusions

Despite a recent remarkable increase in TKA use and differences in demographic features, the causes and risk factors for failures in Korea were similar to those of Western countries. Infection was the most common cause of failure, but loosening has emerged as the most common cause in more recent years, which would prompt us to scrutinize the cause and solution to reduce it.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

TKA is one of the most efficacious, successful, and cost-effective treatments for advanced knee arthritis [4, 8, 32]. In addition, as TKA is being recognized as a standard treatment option for end-stage knee disease, its use has increased steadily over the past few decades [1, 9, 21, 26, 33, 35, 36, 42, 43]. Moreover, the future demand for TKA is projected to increase substantially [12, 20, 27–29] as is the need for revision TKA in the future [27–29]. Although revision TKA is reported to be a reliable and cost-effective procedure for failed TKA [3, 23, 40], it is generally recognized as more technically difficult with inferior outcomes, which are devastating to the patients, and is more expensive than primary TKA. Therefore, a thorough understanding of causes of failure after TKA is necessary to improve surgical and implant performance and minimize risk of failure. In addition, information on trends in performance and demographics of patients who undergo revision TKA would help to establish appropriate healthcare strategies, because this procedure places a considerable economic burden on healthcare resources [3, 27, 28].

Because the causes of failure after TKA are strongly associated with trends in primary TKA use such as emerging new technologies, surgical techniques, and changing demographics, carefully updated information on revision TKA is essential to recognize current failure mechanisms after TKA. Multiple recent epidemiologic studies and nationwide TKA registries in Western countries have documented that the major reasons for revision TKA are infection, loosening, instability, wear, and pain [1, 2, 19, 35, 36, 42–44], whereas the proportion of revision TKA for wear has diminished [11, 41]. However, few studies have elucidated the causes of failure after TKA in Asian patients. Indeed, only one study in the current literature focused on Asian patients and reported that the common causes of TKA failure in Japan were loosening, infection, wear/osteolysis, and instability [22]. Moreover, the causes and risk factors for failure after TKA in Korea have not been elucidated, and the longitudinal trends in revision TKA remain unclear.

We therefore (1) determined the causes of failure after TKA; (2) identified risk factors for failure based on patient demographics and diagnoses listed for the index TKA; and (3) determined the longitudinal trends in revision TKA use and demographics over the past 5 years using a data set compiled by multiple centers in Korea.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively identified 634 revision TKAs and 20,234 primary TKAs performed between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2012, at 19 institutes in Korea, which were affiliated with the Kleos Korea Research Group. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the first author’s hospital. Of the 19 institutes, 16 were secondary or tertiary referral, training hospitals and three were specialized hospitals for knee surgery; 13 were metropolitan and six were located in provincial areas. We included only primary TKAs and revision TKAs after primary TKAs, excluding TKAs after unicompartmental knee arthroplasties and rerevision TKAs. This data set consisted of all the procedures performed at those sites during the time period indicating that the mentioned inclusion criteria were met. Of the 643 TKAs needing revision, 336 (53%) were referred to the 19 Kleos institutes for revision TKA. The mean time to revision was 76.5 months (range, 1–312 months).

All clinical information was collected using a predesigned case report form from the 19 institutes. The clinical information included demographic data, time to revision, the indications for index TKA, causes of failure after index TKA, and types of revision TKA. Demographic data included age, sex, height, weight, and BMI. The indications for index TKA were classified as (1) primary degenerative arthritis; (2) secondary degenerative arthritis such as that after infection, trauma, instability, tumor, and congenital anomaly; (3) inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis; and (4) other causes. The types of revision TKA were classified into (1) all-component revision; (2) femoral component; (3) tibial component; (4) patella component; and (5) tibial polyethylene insert only. The causes of failure were determined by medical records and radiographic findings. They were classified into 11 items based on a standardized complication list and definition of The Knee Society [17], including infection, loosening, wear, osteolysis, instability, periprosthetic fracture, stiffness, malalignment, implant failure (implant fracture or insert dislocation), extensor mechanism failure, and unidentified pain. If there were combined causes of failure, the major reason that was determined to be the most predominant failure mechanism was selected by the surgeon. We also collected demographic information including age, sex, weight, height, and BMI and indication for TKA from the primary TKA group using the same classification as the revision TKA group.

For each cause of failure, we assessed the cumulative incidence, the time-dependent incidence, the age-specific incidence, and time to revision TKA. In addition, we identified the risk factors for overall TKA failure and for each cause of failure and the age-specific risk factors in each age group. Finally, the number of primary and revision TKAs, the number of each revision type, the proportion of each cause and demographic data in each year during the study period, and the age-specific performance of revision TKAs were assessed to investigate trends in revision TKAs.

The cumulative incidence of each cause of failure was determined by calculating the incidence of each of the 11 causes of 634 revision TKAs during the study period. To determine the time-dependent incidence for each cause, the incidences according to the time period from index TKA to revision TKA were assessed and plotted against time. To evaluate the function of age, it was adjusted to the age at index TKA, which was calculated by subtracting the time to revision (years) from age at revision TKA, and then it was categorized into three groups: younger than 65 years, 65 to 74 years, and 75 years or older. The revision burden was calculated by dividing the number of revision TKAs by the total number of primary and revision TKAs [34]. Difference in distribution of failure causes among those three age groups was compared using the chi-square test, and differences in time to revision and the revision burden of each cause of failure among those three age groups were compared using ANOVA. To identify predictors for failure after TKA and each cause of failure, we performed univariate comparisons between the overall revision TKA group and the primary TKA group and between each cause of failure and the primary TKA group. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for overall failure after TKA and each cause. Univariate comparisons were performed for the demographic data (sex, age, height, weight, and BMI) and the indications for index TKA. The statistical significance of differences between the revision TKA group and primary TKA group was determined with the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables. Variables with p < 0.1 on univariate analysis were used for multivariate logistic regression analysis and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to account for potentially confounding variables. To identify age-specific risk factors, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for each of the three age groups. Finally, trends in revision TKA were determined by assessing the annual number of primary and revision TKAs, the revision burden, the annual number of each revision type, the annual proportion of each cause, and annual demographic data (age, sex, weight, height, BMI, incidence of obesity) between 2008 and 2012. Chi-square tests were used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for continuous variables. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS® for Windows (Version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

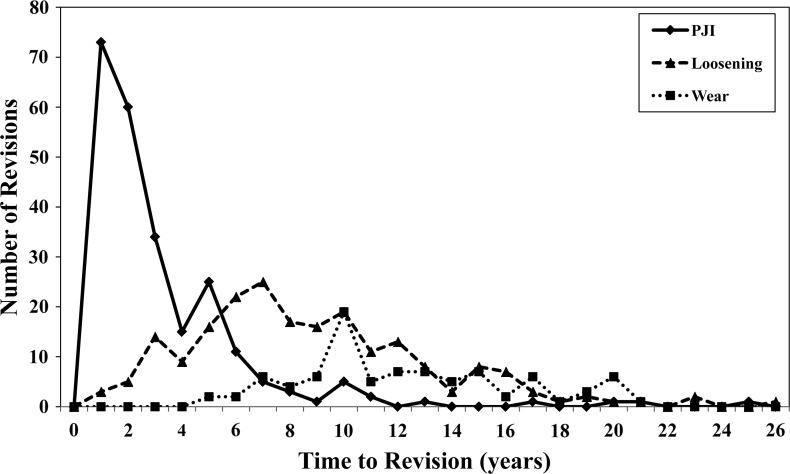

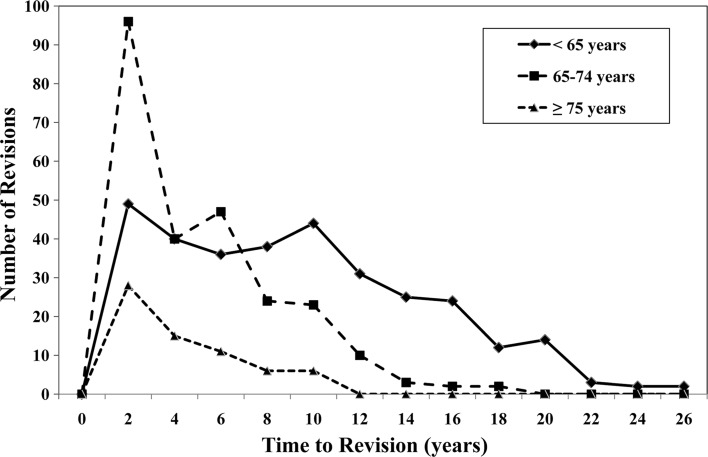

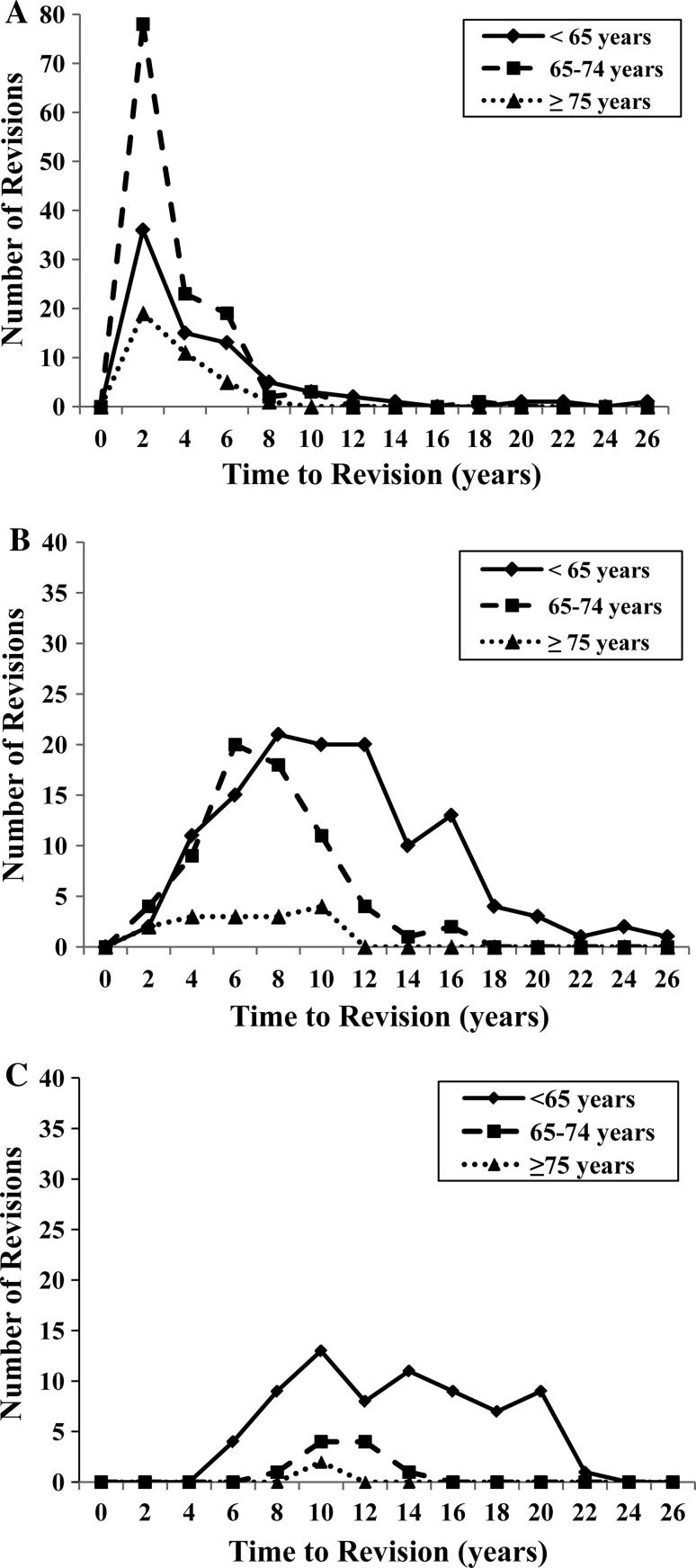

The most common cumulative cause of TKA failure in the past 5 years was infection (38%) followed by loosening (33%), wear (13%), instability (7%), and stiffness (3%). Each cause had a different time-dependent incidence pattern and age-specific distribution. Infection was the most common cause of failure within the first 2 years (77%), whereas loosening was the most common cause of failure after 2 years (44%; Table 1). In addition, the incidence of infection reached a peak during the first 2 years and declined rapidly thereafter, whereas the incidence of loosening and wear increased slowly from 2 years after TKA and overtook infection to become the most common reason 6 years after TKA (Fig. 1). Among patients younger than 65 years, loosening (38%) was the most common cause of failure followed by infection (24%) and wear (22%), whereas infection (50%), loosening (26%), and instability (7%) were common failure causes in the 65 years or older age group (p < 0.001). In addition, time to revision for all causes of failure decreased with increasing age and had a different time-dependent pattern (Fig. 2); thus, patients younger than 65 years of age had the longest time to revision (103 months), whereas the 75 years or older age group had the shortest time to revision (41 months, p < 0.001; Table 2). Moreover, each cause of failure had quite different age-specific patterns (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Cumulative causes of failure after TKA over the last 5 years*

| Causes | Overall | Time to revision | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 2 years | > 2 years | ||

| Infection | 239 (38) | 133 (77) | 106 (23) |

| Loosening | 207 (33) | 6 (4) | 201 (44) |

| Wear | 83 (13) | 0 | 83 (18) |

| Instability | 41 (7) | 16 (9) | 25 (5) |

| Stiffness | 16 (3) | 9 (5) | 7 (2) |

| Implant failure | 14 (2) | 3 (2) | 11 (2) |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 13 (2) | 2 (1) | 11 (2) |

| Osteolysis | 10 (2) | 0 | 10 (2) |

| Extensor mechanism failure | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Malalignment | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Unidentified pain | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Total | 634 | 172 (27) | 462 (73) |

* Data are presented as numbers with percentages in parentheses.

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the time-dependent variation in the incidences of the causes of TKA failure. Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) increased rapidly, peaked at 1 year after TKA, and declined rapidly thereafter. Loosening and wear increased slowly, peaked 7 to 10 years after TKA, and then declined slowly.

Fig. 2.

A graph shows age-specific trends in the time at which revision TKAs were performed. Revision TKAs reached a peak 2 years after TKA in all age groups, declined thereafter in the 65 years or older age group, and decreased slowly 10 years after TKA in the younger than 65 years age group.

Table 2.

Comparisons of failure causes and time to revision according to the age at index TKA

| Failure causes and time to revision | < 65 years | 65–74 years | ≥ 75 years | Overall | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of failure* | |||||

| Infection | 78 (24) | 125 (50) | 36 (55) | 239 (38) | < 0.001 |

| Loosening | 123 (38) | 69 (28) | 15 (23) | 207 (33) | |

| Wear | 71 (22) | 10 (4) | 2 (3) | 83 (13) | |

| Instability | 17 (5) | 20 (8) | 4 (6) | 41 (7) | |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 3 (1) | 7 (3) | 3 (5) | 13 (2) | |

| Stiffness | 8 (3) | 6 (2) | 2 (3) | 16 (3) | |

| Others | 20 (6) | 11 (4) | 4 (6) | 35 (6) | |

| Time to revision (months) | |||||

| Overall | 103 | 52 | 41 | 76 | < 0.001 |

| Infection | 48 | 29 | 28 | 35 | 0.002 |

| Loosening | 120 | 81 | 67 | 103 | < 0.001 |

| Wear | 152 | 124 | 120 | 148 | 0.177 |

| Instability | 54 | 47 | 21 | 47 | 0.369 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 120 | 72 | 51 | 78 | 0.282 |

| Stiffness | 65 | 63 | 20 | 58 | 0.698 |

| Others | 85 | 62 | 48 | 73 | 0.400 |

* Data are presented as numbers with percentages in parentheses.

Fig. 3A–C.

Graphs show age-specific trends in TKA performance according to the three major indications of revision TKA: (A) periprosthetic joint infection (PJI); (B) loosening; and (C) wear. (A) Revision TKAs resulting from PJI peaked 2 years after TKA with the largest proportion in the 65 to 74 years age group. (B) Revision TKAs resulting from loosening peaked 6 years after TKA, decreased thereafter in the 65 to 74 years age group, and peaked later and declined slowly in the younger than 65 years age group. (C) Most of the revision TKAs resulting from wear occurred in the younger than 65 years age group, reached a peak 10 years after TKA, and continued 20 years after TKA.

Young age at the time of index TKA and male sex were identified as risk factors for failure after TKA overall, and male sex and nonprimary degenerative arthritis as indications for index TKA were predictors for failure in the younger than 65 years age group (Table 3). Univariate comparisons revealed several demographic factors such as age at the time of index TKA, sex, and indication for index TKA that differed between the primary and revision TKA groups and the primary TKA and each failure group. Multivariate regression analysis revealed that the overall risk for TKA failure decreased by 60% for every 10 years of age increase at index TKA (OR per 10 years of age increase, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.37–0.49). The risks of wear and loosening were decreased by 80% and 70%, respectively, for every 10 years of age increase (OR per 10 years of age increase, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.15–0.26 for wear; OR per 10 years of age increase, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.25–0.35 for loosening) (Table 3). The overall risk for revision was increased by 1.9-fold for males (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.42–2.49), and the risks for infection and stiffness were increased by 2.3-fold (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.51–3.40) and 6.7-fold (OR, 6.68; 95% CI, 1.78–25.41), respectively. The risk for failure was increased by 1.6-fold for males (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.03–2.32) and 1.8-fold for nonprimary degenerative arthritis as indications for index TKA (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.20–2.59) in the younger than 65 years age group. However, no significant risk factor was identified in the 75 years or older age group.

Table 3.

Risk factors identified in multivariate regression analyses for the failures from five major causes and failures in three different age groups

| Risk factors | Number (%) | Factor | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 634 (100) | Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.41 (0.37–0.45) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.88 (1.42–2.49) | < 0.001 | ||

| Five major causes | ||||

| Infection | 239 (38) | Male sex | 2.27 (1.51–3.40) | < 0.001 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.66 (0.56–0.78) | < 0.001 | ||

| Loosening | 207 (33) | Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.30 (0.25–0.35) | < 0.001 |

| Wear | 83 (13) | Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.20 (0.15–0.26) | < 0.001 |

| Instability | 41 (7) | Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | < 0.001 |

| Stiffness | 16 (3) | Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 6.68 (1.78–25.41) | 0.005 | ||

| Three groups by the age at index surgery | ||||

| < 65 years | 320 (51) | Male sex | 1.55 (1.03–2.32) | 0.034 |

| Secondary degenerative arthritis | 1.77 (1.20–2.59) | 0.004 | ||

| 65–74 years | 248 (39) | Male sex | 2.38 (1.57–3.63) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 75 years | 66 (10) | No significant risk factor | ||

Over the past 5 years, annual numbers of revision TKA increased notably, and the most common cause of failure changed with no differences identified in the types of revision TKAs and demographic characteristics of patients undergoing revision TKAs (Table 4). The annual numbers of revision TKAs in the more recent 3 years increased from the number of 2008 by more than 23%. However, the revision burden, defined as the percentage of revision TKAs in all primary and revision TKAs, remained at a similar level, approximately 3%; the annual numbers of primary TKAs increased as well. In the first 2 years, infection was the most common cause of failure (54% in 2008 and 41% in 2009), but in the more recent 3 years, loosening was the most common cause (33% in 2010, 40% in 2011, and 35% in 2012). Other failure causes showed similar orders and percentages over the 5 years, namely, wear of approximately 13%, instability of 7%, stiffness of 3%, and periprosthetic fracture of 2%. No notable patterns of changes were identified in the revision types and demographic characteristics of patients undergoing revision TKAs.

Table 4.

Trends in revision TKA over the last 5 years (2008–2012)

| Variable | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKAs (number of knees) | ||||||

| Revision TKA (% increase) | 109 | 111 | 136 | 144 | 134 | 634 (23%) |

| Primary TKA (% increase) | 2806 | 3615 | 4954 | 4456 | 4403 | 20234 (57%) |

| Revision burden* | 3.8% | 3.0% | 2.7% | 3.1% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Causes of failures (%) | ||||||

| Infection | 54 | 41 | 29 | 36 | 33 | 38 |

| Loosening | 25 | 27 | 33 | 40 | 35 | 33 |

| Wear | 11 | 14 | 20 | 9 | 12 | 13 |

| Instability | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Stiffness | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Others | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Revision type (knee number with percentage in parentheses) | ||||||

| All components | 98 (90) | 94 (85) | 118 (87) | 132 (92) | 105 (78) | 547 (87) |

| Femur alone | 0 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (2) | 0 | 5 (4) | 11 (2) |

| Tibia alone | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 8 (6) | 7 (5) | 27 (4) |

| Patella alone | 0 | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 6 (1) |

| Polyethylene insert alone | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 12 (9) | 3 (2) | 17 (13) | 43 (7) |

| Demographics (mean) | ||||||

| Age at revision TKA (years) | 69 | 70 | 69 | 71 | 72 | 70 |

| Sex (female, %) | 82 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 84 | 86 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 | 26.1 | 25.6 | 26.6 | 27.0 | 26.3 |

| Secondary degenerative arthritis | 11% | 9% | 11% | 8% | 5% | 9% |

* Revision burden was defined as the percentage of revision TKAs in all primary and revision TKAs performed during the study period [34].

Discussion

The cause of failure after TKA depends on a number of factors, including changes in patient demographics, surgical techniques, and, sometimes, emerging technologies failing to meet expectations. An understanding of the most common failure mechanisms after TKA and risk factors for these failures is essential to help guide our choices of techniques and approaches. In addition, current information on trends in revision TKA is important to establish appropriate healthcare strategies regarding future demand for revision TKA. The current TKA use in Korea has reached that of Western countries over the past 10 years owing to the rapid growth of primary TKA use; however, the demographic trends in Korea differ from those of Western countries. In Korea, the proportion of elderly patients (≥ 65 years) is higher than in other countries and there is a ninefold higher female predominance [25]. We therefore determined causes, risk factors, and longitudinal trends in revision TKAs over the past 5 years based on the clinical records of 19 institutes in Korea.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, because we evaluated only Korean patients, the demographic characteristics and lifestyle of our study population should be noted before extrapolating our findings to other populations. Some salient differences to consider might include more frequent varus knee deformity [6, 7, 31], more frequent squatting and kneeling in daily activities [15, 24], the higher use of TKA in elderly patients (≥ 65 years), and a pronounced female predominance [25]. Second, the present study was retrospective, but we classified the causes of failure according to a recently defined standardized complication list proposed by The Knee Society [17]. Some causes of failure did not exactly meet the criteria, especially for infection, and a more validated definition of each kind of failure using broad-based clinical practice data would help studies like ours better classify failures; we believe that validation of complication lists like those of The Knee Society [17] will help us better understand current TKA failure mechanisms. Third, because we only recorded age, sex, weight, height, and BMI for the patient demographics, we were unable to account for the potential effect of other patient characteristics that might be strongly associated with TKA failure such as patient comorbidities, preoperative deformities and functional status, activity level, socioeconomic status, and education level. Fourth, we did not take into account the potential impact of implant characteristics and surgical techniques such as a mobile-bearing, high-flexion design, minimally invasive technique, navigation, and patient-specific implants. Likewise, we did not classify the type of loosening and wear based on each component. The lack of these data does not allow us to draw conclusions about implant-specific or technique-specific causes of failures. Fifth, our study also did not consider surgeon or hospital statistics such as the number of TKAs performed annually or number of hospital beds. These data would better enable us to understand the current failure mechanisms and risk factors for failure. Future studies should investigate these issues in more detail. Finally, there is concern over whether this study accurately represents the nationwide trends regarding TKA performance in Korea. However, our current data accounted for approximately 10% of primary and revision TKAs in Korea during this study period, lending our study validity in this respect. Despite these limitations, this study is the largest series regarding revision TKA trends in an Asian population and can provide valuable information on failure mechanisms after TKA.

Our findings suggest that the current major reasons for revision TKA in Korea are infection, loosening, and wear and that each cause of failure has different trends in age-specific performance of revision TKAs. In this study, infection (38%), loosening (33%), wear (13%), instability (7%), and stiffness (3%) were the major reasons for revision TKA during the past 5 years. Our study concurs with recent nationwide TKA registry reports (Table 5) and with previous studies (Table 6) that have reported infection, loosening, wear, and instability as current major failure mechanisms, except for a higher proportion of patellar resurfacing (14%–23% in Western countries versus 1% in this study) and unidentified pain (9%–31% in Western countries versus 0.3% in this study) in nationwide TKA registry data in Western countries [1, 2, 19, 22, 35, 36, 42–44]. The reason why the incidence of unidentified pain was higher in TKA registry reports is unclear, but it may be associated with the use of different definitions of failures among countries. In addition, 10 years ago, wear was reported as the most prevalent failure mechanism, accounting for 56% of all revision TKAs [41], and early failures of cementless implants were reported to account for 13% [11]. Our findings, along with those of previous studies, indicate that causes of failure are changing as emerging technologies and surgical techniques for TKA change, and the incidence of implant performance-related failure has decreased over the past decade. On the other hand, there were notable associations between the causes and time to revision in relation to the primary TKA, and the incidence of each cause was affected by the age at index TKA. Surgeons should recognize the recent trends in failure mechanisms and be aware of the most likely causes for failure for each age group to improve surgical performance and postoperative management after TKA.

Table 5.

Summary of nationwide TKA registry reports

| Country | Australia [1] | England and Wales [35] | New Zealand [36] | Norway [42] | Sweden [43] | Current study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registry | NJRR | NJR | NZJR | NAR | SKAR | N/A |

| Record period | 2003–2012 | 2011–2012 | 1999–2011 | 1994–2009 | 2001–2010 | 2008–2012 |

| Revision number | 31,698 | 5135 | 4603 | 3445 | 3104 | 634 |

| Revision burden | 8.3 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 3.0 |

| Time to revision (months) | N/P | N/P | 88.6 | N/P | N/P | 77 |

| Age (years) | 65–74 | 69.5 | 68.8 (female), 68.1 (male) | N/P | N/P | 70 |

| Female (%) | 51 | 51 | 52 | N/P | N/P | 86 |

| Cause of failures* | ||||||

| 1 | Loosening† (30) | Loosening (35) | Loosening‡ (37) | Pain (27) | Loosening | Infection (38) |

| 2 | Infection (22) | Infection (23) | Pain (31) | Loosening‡ (24) | Infection | Loosening (33) |

| 3 | Patellofemoral pain (14) | Pain (16) | Infection (24) | Infection (13) | Patellar resurfacing | Wear (13) |

| 4 | Pain (9) | Instability (14) | Patellar resurfacing (23) | Instability (10) | Instability | Instability (7) |

| 5 | Instability (6) | Lysis (10), wear (10) | Instability (7) | Wear§ (5) | Wear | Stiffness (3) |

* Failure causes are listed in the order of the percent given in parentheses if available; † loosening was classified as loosening/lysis in the original report [1]; ‡ all tibial, femoral, and patellar component loosenings were added; § wear was classified as “defect polyethylene” in the original report [41]; the proportion of indications was presented as a graph only [43]; revision burden was defined as the ratio of revision TKAs to the total number of primary and revision TKAs [34]; NJRR = National Joint Replacement Registry; NJR = National Joint Registry; NZJR = New Zealand Joint Registry; NAR = Norwegian Arthroplasty Register; SKAR = Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register; N/A = not available; N/P = not presented.

Table 6.

Summary of previous studies reporting revision burden and failure causes in the literature

| Study (year) | Country (data source) | Study period | Number of cases | Revision burden (%) | Age (years) | Female (%) | Causes of TKA failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes (%) | Time to revision (months) | |||||||

| Fehring et al. (2001) [11] | USA (1 institute) | 1986–1999 | 440 | N/P | N/P | N/P | Infection (38), | 19.4, |

| instability (27), | 19.0, | |||||||

| failure of ingrowth (13) | 27.3 | |||||||

| Sharkey et al. (2002) [41] | USA (1 institute) | 1997–2000 | 212 | N/P | Male: 68.7, female: 68.4 | 63 | Wear (25), | Early: 13.2, |

| loosening (24), | late: 84 | |||||||

| instability (21) | ||||||||

| Vessely et al. (2006) [44] | USA (1 institute) | 1987–1989 | 45 | N/P | N/P | N/P | Infection (36), | N/P |

| loosening (20), | ||||||||

| wear (16) | ||||||||

| Bozic et al. (2010) [2] | USA (†NIS) | 2005–2006 | 60,355 | N/P | 66 | 57 | Infection (25), | N/P |

| loosening (16), | ||||||||

| implant failure/breakage (10) | ||||||||

| Hossain et al. (2010) [19] | UK (1 institute) | 1999–2008 | 349 | N/P | 68 | 41 | Infection (33), | 84.3 |

| loosening (15), | ||||||||

| wear (12) | ||||||||

| Kasahara et al. (2013) [22] | Japan (5 institutes) | 2006–2011 | 140 | 3.3 | 73 | 81 | Loosening (40), | 74 |

| infection (24), | 31 | |||||||

| wear/lysis (9), | 139 | |||||||

| instability (9) | 91 | |||||||

| Current study | Korea (19 institutes) | 2008–2012 | 634 | 3.0 | 70 | 86 | Infection (38), | 35 |

| aseptic loosening (33), | 103 | |||||||

| wear (13) | 148 | |||||||

* Revision burden was defined as the percentage of revision TKAs in all primary and revision TKAs [34]; NIS = Nationwide Inpatient Survey; N/P = not presented.

In this study, male sex and younger age at the index TKA were identified as the risk factors for failures, but to our surprise, obesity, which is a well-documented risk factor for TKA failure [10, 13, 38], was not a major risk factor. Our finding of no association between obesity and TKA failure may be associated with a relatively low prevalence of severe obesity in Asian patients. This interpretation was echoed by a previous study reporting that obesity was not a risk factor for TKA failures in Japanese patients [22]. On the other hand, the identified risk factors, male sex and younger age, concur with previous studies reporting a higher revision rate for younger patients [1, 14, 18, 23, 34, 39, 45], a higher association between wear and young age [19, 37], and a higher incidence of infection in males [1, 22]. However, this study does not provide clues to understand why male sex increases the risk for infection, and future studies are warranted to elucidate this issue and to reduce infection in male patients. Nonetheless, our findings indicate, despite improvement of surgical technique and implant performance, implant longevity must still be improved in younger, active patients.

Our data suggest although the incidence of revision TKAs has increased and the distribution of failure mechanism has changed, demographic characteristics of patients undergoing revision TKAs remained stable. In this study, the annual number of both primary and revision TKAs increased by 57% and 23%, respectively, and the incidence of loosening has increased and exceeds that of infection recently. However, the demographics of patients with revision TKA did not change over the period of our study. Our data concur with nationwide TKA registry reports in Western countries that found an increase in the overall number of revision TKAs with stable demographics [1, 5, 35, 36]. Our findings, along with those of previous reports, indicate that appropriate healthcare strategies for preparing the future demand for revision TKA such as ensuring adequate hospitals and workforce for TKAs and revisions and providing adequate reimbursement should be established [12, 20, 29, 30]. Also needed is a better understanding of the reasons why the proportion of loosening has increased recently. It may be associated with a high rate of early femoral component loosening after high-flexion TKA designs in Korean, which was reported to be associated with postoperative high-flexion activities [15, 16]. Carefully updated epidemiologic studies on revision TKA reflecting current TKA technologies based on more detailed demographic features are needed to find the reason and solution for the recent increase in loosening in Korea.

This study demonstrates that despite a recent remarkable increase in TKA use and different demographic features in Korea, the causes and risk factors for revision TKA are similar to those of Western countries. Infection is the most common cumulative cause of failure, but loosening has emerged as the most common cause in more recent years, which would prompt us to scrutinize the cause and solution to reduce it. The findings of male sex and younger age at index TKA as risk factors for revision emphasize that special efforts should be made to improve the durability of TKA in these young active patients across the countries. The information that this study provides on cause of failures, risk factors, and temporal patterns of revision TKAs should be considered to establish appropriate strategies for meeting the future demands for revision TKA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chong Bum Chang MD (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea); Sung Ryong Shin MD, Sang Bum Kim MD, Jong Won Kim MD, Duck Hyun Choi MD, Ki Hyun Jo MD, and Nong Kyoum Ahn MD (Himchan Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Yong Bum Park MD, and Sug Jun Kim MD (KS Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Gwang Chul Lee MD (Chosun University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea); and Yong Chan Kim MD, and Chul Jun Choi MD (Yonsei Sarang Hospital, Bucheon, Korea) for their assistance in furnishing data. We also thank Seongeun Byun MD (Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea); Jae-Woong Yoon MD, and Kyo-Sun Lee MD (St Paul’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Hyuk Park MD (Chonbuk National University Hospital, Kunsan, Korea); Jong-Min Park MD (St Vincent’s Hospital, Suwon, Korea); Ho Hyun Won MD, and Yeon Gwi Kang MS (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea); Bum Yong Park MD (Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Jun Gyu Lee MD (Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea); Hye Sun Ahn MS (Himchan Hospital, Seoul, Korea); and Seon Hwa Lee MS (Yonsei Sarang Hospital, Bucheon, Korea) for their assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

The Kleos Korea Research Group: Ju-Hong Lee MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Kunsan, Korea); Dong Hwi Kim MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chosun University Hospital, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea); Lih Wang MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Dong-A University Hospital, Dong-A University College of Medicine, Pusan, Korea); Ji Hyun Ahn MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Ilsan, Korea); Young-Joon Choi MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Gangneung Asan Hospital, Ulsan University School of Medicine, Gangneung, Korea); Jong-Heon Kim MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Guri Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Guri, Korea); Ju-O Kim MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Gwang-Ju Veterans Hospital, Gwangju, Korea); Kwang-Am Jung MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Himchan Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Kwang-Jun Oh MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Konkuk University Medical Center, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Byung June Chung MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, KS Hospital, Seoul, Korea); HyungTaek Park MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Maryknoll Hospital, Pusan, Korea); Jae Doo Yoo MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Yong In MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Hae Seok Koh MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, St Vincent’s Hospital, Suwon, Korea); Sae Kwang Kwon MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yonsei Sarang Hospital, Bucheon, Korea); In Jun Koh MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Uijeongbu St Mary’s Hospital, Gyeonggi-do, Korea; The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Woo-Shin Cho MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Asan Medical Center, Ulsan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Nam Yong Choi MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, St Paul’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); and Tae Kyun Kim MD (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea).

One or more of the authors (IJK, W-SC, NYC, TKK) have received during the study period (USD 10,000 to USD 100,000) from Smith & Nephew (Memphis, TN, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this Investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Uijeongbu St Mary’s Hospital (Gyeonggi-do, Korea) affiliated with the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine (Seoul, Korea).

References

- 1.Australian Orthopaedic Association (AOA). National Joint Replacement Registry (NJRR) Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Annual Report. 2012. Available at: www.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/aoanjrr/documents/AnnualReports2012/AnnualReport_2012_WebVersion.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2013.

- 2.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0945-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns AW, Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, MacDonald SJ, Rorabeck CH. Cost effectiveness of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:29–33. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214420.14088.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271:1349–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510410061034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI). Canadian Joint Replacement Registry (CJRR) Hip and Knee Replacement in Canada 2007 Annual Report. Available at: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/2007CJRRAnnualReport%20(web).pdf. 20. Accessed Feburary 10, 2013.

- 6.Chang CB, Choi JY, Koh IJ, Seo ES, Seong SC, Kim TK. What should be considered in using standard knee radiographs to estimate mechanical alignment of the knee? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CB, Koh IJ, Seo ES, Kang YG, Seong SC, Kim TK. The radiographic predictors of symptom severity in advanced knee osteoarthritis with varus deformity. Knee. 2011;18:456–460. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang RW, Pellisier JM, Hazen GB. A cost-effectiveness analysis of total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip. JAMA. 1996;275:858–865. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530350040032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culliford DJ, Maskell J, Beard DJ, Murray DW, Price AJ, Arden NK. Temporal trends in hip and knee replacement in the United Kingdom: 1991 to 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:130–135. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Obese diabetic patients are at substantial risk for deep infection after primary TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1577–1581. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315–318. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehring TK, Odum SM, Troyer JL, Iorio R, Kurtz SM, Lau EC. Joint replacement access in 2016: a supply side crisis. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foran JR, Mont MA, Etienne G, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. The outcome of total knee arthroplasty in obese patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1609–1615. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gioe TJ, Novak C, Sinner P, Ma W, Mehle S. Knee arthroplasty in the young patient: survival in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:83–87. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31812f79a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han HS, Kang SB. Brief followup report: does high-flexion total knee arthroplasty allow deep flexion safely in Asian patients? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1492–1497. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2628-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han HS, Kang SB, Yoon KS. High incidence of loosening of the femoral component in legacy posterior stabilised-flex total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1457–1461. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.19840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healy WL, Della Valle CJ, Iorio R, Berend KR, Cushner FD, Dalury DF, Lonner JH. Complications of total knee arthroplasty: standardized list and definitions of the Knee Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2489-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Himanen AK, Belt E, Nevalainen J, Hamalainen M, Lehto MU. Survival of the AGC total knee arthroplasty is similar for arthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis Finnish. Arthroplasty Register report on 8,467 operations carried out between 1985 and 1999. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:85–88. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hossain F, Patel S, Haddad FS. Midterm assessment of causes and results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1221–1228. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorio R, Robb WJ, Healy WL, Berry DJ, Hozack WJ, Kyle RF, Lewallen DG, Trousdale RT, Jiranek WA, Stamos VP, Parsley BS. Orthopaedic surgeon workforce and volume assessment for total hip and knee replacement in the United States: preparing for an epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1598–1605. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain NB, Higgins LD, Ozumba D, Guller U, Cronin M, Pietrobon R, Katz JN. Trends in epidemiology of knee arthroplasty in the United States, 1990–2000. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3928–3933. doi: 10.1002/art.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasahara Y, Majima T, Kimura S, Nishiike O, Uchida J. What are the causes of revision total knee arthroplasty in Japan? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1533–1538. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2820-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keeney JA, Eunice S, Pashos G, Wright RW, Clohisy JC. What is the evidence for total knee arthroplasty in young patients? A systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:574–583. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1536-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HA, Kim S, Seo YI, Choi HJ, Seong SC, Song YW, Hunter D, Zhang Y. The epidemiology of total knee replacement in South Korea: national registry data. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:88–91. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koh IJ, Kim TK, Chang CB, Cho HJ, In Y. Trends in use of total knee arthroplasty in Korea from 2001 to 2010. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1441–1450. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2622-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1487–1497. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2606–2612. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Mowat F, Saleh K, Dybvik E, Karrholm J, Garellick G, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Malchau H, Lau E. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:144–151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Zhao K, Mowat F, Lau E. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasam MP, Lee KJ, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim TK. Femoral lateral bowing and varus condylar orientation are prevalent and affect axial alignment of TKA in Koreans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1472–1483. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavernia CJ, Guzman JF, Gachupin-Garcia A. Cost effectiveness and quality of life in knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Losina E, Thornhill TS, Rome BN, Wright J, Katz JN. The dramatic increase in total knee replacement utilization rates in the United States cannot be fully explained by growth in population size and the obesity epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:201–207. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, Garellick G, Soderman P. The Swedish Total Hip Replacement Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:2–20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200200002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Joint Registry (NJR) for England and Wales. 9th Annual Report. 2012. Available at: www.njrcentre.org.uk/NjrCentre/Portals/0/Documents/NJR%209th%20Annual%20Report%202012.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2013.

- 36.New Zealand Orthropaedic Association. The New Zealand Joint Registry Thirteen Year Report. 2012. Available at: www.cdhb.govt.nz/NJR/reports/A2D65CA3.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2013.

- 37.Odland AN, Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Wells CW. Wear and lysis is the problem in modular TKA in the young OA patient at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1429-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1710–1715. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0209-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rand JA, Trousdale RT, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS. Factors affecting the durability of primary total knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:259–265. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200302000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh KJ, Rand JA, McQueen DA. Current status of revision total knee arthroplasty: how do we assess results? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:S18–S20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7–13. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) Report June 2010. Available at: http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/Report_2010.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2013.

- 43.The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR). Annual Report 2012. Available at: www.knee.nko.se/english/online/uploadedFiles/117_SKAR2012_Engl 1.0.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2013.

- 44.Vessely MB, Whaley AL, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Berry DJ. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: Long-term survivorship and failure modes of 1000 cemented condylar total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:28–34. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229356.81749.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.W-Dahl A, Robertsson O, Lidgren L. Surgery for knee osteoarthritis in younger patients. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:161–164. doi: 10.3109/17453670903413186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]