Abstract

Purpose

The mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin) pathway is constitutively activated in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). mTOR inhibitors (mTORi) have activity in DLBCL, although response rates remain low. We evaluated DLBCL cell lines with differential resistance to the mTORi Rapamycin, in order to (A) identify gene-expression profile(s) (GEP) associated with resistance to Rapamycin, (B) understand mechanisms of Rapamycin resistance, and (C) identify compounds likely to synergize with mTORi.

Experimental Design

We sought to identify a GEP of mTORi resistance by stratification of eight DLBCL cell lines with respect to response to Rapamycin. Then, using pathway analysis and connectivity mapping, we sought targets likely accounting for this resistance, and compounds likely to overcome it. We then evaluated two compounds thus identified for their potential to synergize with Rapamycin in DLBCL, and confirmed mechanisms of activity with standard immunoassays.

Results

We identified a GEP capable of reliably distinguishing Rapamycin resistant from Rapamycin sensitive DLBCL cell lines. Pathway analysis identified Akt as central to the differentially expressed gene network. Connectivity mapping identified compounds targeting Akt as having a high likelihood of reversing the GEP associated with mTORi resistance. Nelfinavir and MK-2206, chosen for their Akt-inhibitory properties, yielded synergistic inhibition of cell viability in combination with Rapamycin in DLBCL cell lines, and potently inhibited phosphorylation of Akt and downstream targets of activated mTOR.

Conclusions

GEP identifies DLBCL subsets resistant to mTORi therapy. Combined targeting of mTOR and Akt suppresses activation of key components of the Akt/mTOR pathway and results in synergistic cytotoxicity. These findings are readily adaptable to clinical trials.

Introduction

Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). Approximately 30% of patients relapse and die of these aggressive tumors despite chemotherapy and stem cell transplant (1). Therefore, new treatment approaches for DLBCL are urgently needed.

The mTOR pathway is constitutively activated in NHL, and mTOR inhibition has emerged as a potential therapeutic option for solid tumors, especially Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) (2), and the NHL subtypes Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) (3) and DLBCL (4). Rapamycin, the prototypical mTOR inhibitor, binds to the immunophilin FKBP, and inhibits cell cycle progression by blocking cytokine-mediated signal transduction pathways. This interrupts downstream signals that regulate gene expression, cellular metabolism, and apoptosis (5). However, response rates to mTOR inhibitors remain approximately 30% in DLBCL (6). Mechanisms of resistance to mTOR inhibition are poorly understood (3), (7). Gene expression profiling (GEP) is an important tool to recognize genes and pathways responsible for resistance to chemotherapeutic agents (8). To date, GEP has not only been helpful in the delineation of prognostically important subtypes of DLBCL, but also in identifying potentially important targets and therapies (9).

We sought to identify and explore in a pre-clinical model the gene expression signature associated with differences in resistance to Rapamycin in DLBCL. This gene signature proved to be an accurate biomarker for predicting response to Rapamycin in DLBCL cell lines. Since differentially expressed genes associated with resistance to Rapamycin are enriched for the Akt pathway, we investigated the potential for Akt-inhibitors to augment the anti-lymphoma effect of Rapamycin. We specifically tested Nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor (PI) used in the treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, and MK-2206, an orally bioavailable compound currently in early-phase trials in patients with solid tumors. Our results demonstrate synergism between Akt inhibitors and Rapamycin in reduction of DLBCL cell viability, inhibition of downstream genes in the Akt pathway, and interruption of feedback between mTOR inhibition and Akt.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, culture conditions, and drug treatment

DLBCL cell lines Farage, Karpas-422, OCI-Ly1, OCI-Ly3, OCI-Ly18, OCI-Ly19, Pfeiffer, SUDHL-4, SUDHL-6, SUDHL-8, Toledo, and WSU-NHL, and breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB 231 and MDA-MB 468, were each cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro; Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio-Products), 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Cellgro), at 37°C with humidification. Rapamycin was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), MK-2206 from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX), and Vinblastine from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Each drug was formulated at stock solutions between 200 nM and 1 uM. Doxorubicin was obtained from Teva Pharmaceuticals (Irvine, CA) and formulated at 500 nM. Purified Nelfinavir was a generous gift from Pfizer (Groton, CT), and was formulated at 200 uM, after dissolution in DMSO. All drugs were stored at between −20 and −88°C. Cells were treated in series of eight 100 ul wells for 48 hours for viability assessment, and in 4 ml wells in triplicate, for 24 hours, for flow cytometry and to determine protein amounts.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by a fluorometric resazurin reduction method (CellTiter-Blue; Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. The number of viable cells in each treated well was calculated 48 hours after treatment. Cells (100 uL; 105 cells per well for lymphoma cell lines and 4×103 cells per well for breast cancer cell lines) were plated in 96-well plates (8 replicates per condition), with 20 uL of CellTiter-Blue Reagent (Promega) added to each well. After 1 hour of incubation with the dye (2 hours for breast cancer cell lines), fluorescence (560Ex/590Em) was measured with the Polarstar Optima microplate reader (BMG Lab Technologies). The number of viable cells in each treated well was calculated, based on the linear least-squares regression of the standard curve. Cell viability in drug-treated cells was normalized to their respective untreated controls. Cell counts were confirmed on the Countess automated cell counter (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's specifications.

Gene expression arrays and analysis

Gene expression data were obtained using the Affymetrix HuGene ST 1.0 GeneChip; mRNA isolation, labeling, hybridization, and quality control were carried out as described previously (10). Raw data were processed using the Robust Multi-Averaging (RMA) algorithm and Affymetrix Expression Console software. Data are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE27255; National Center for Biotechnology Information, Gene Expression Omnibus database. http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). A total of 33,297 probes were measured on the array. The association between gene expression and cell line resistance was assessed first using a conventional T-test, and second with a modified T-test employed by the eBayes function in limma (R version 9.2) (11)(12). The final set of candidates was defined as those genes differentially expressed between resistant and sensitive cell lines with a p-value, by both methods, below 0.03. This cutoff was chosen in order to provide a reasonably-sized set of genes that was felt likely to retain predictive power. Pathway Analysis was performed using Ingenuity (http://www.ingenuity.com/products/pathways_analysis.html). In this program, the Core Analysis function was selected, and default analysis settings were maintained (Direct and Indirect Relationships; Maximum 35 Molecules per Network; Maximum 25 Networks per Analysis), with the exception of cell lines, which were limited to Lymphoma.

In order to predict resistance patterns of additional cell lines not included in the training set (see “Results,” first section), the collection of genes was analyzed using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) prediction module from Gene Pattern software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern/). A Support vector machine (with linear kernel) uses all gene expression values as input and fits a classifying line, with the largest margin separating the two classes (resistant vs. sensitive cell lines), in this feature space, which has as many dimensions as the number of genes submitted. This classifying line, also called a hyperplane, is then used to classify each unknown cell line (in our case as either “sensitive” or “resistant”) based upon which side of the hyperplane each test case falls.

The GEP data was then analyzed with the Broad Institute's Connectivity Map (cmap) database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cmap/index.jsp), using the same set of differentially expressed genes in resistant vs. sensitive cell lines. With cmap, our imported query was compared with established signatures of therapeutic compounds (or “perturbagens”). Each compound was assigned a connectivity score (from +1 to -1), representing relative association with our specific query. Compounds with connectivity scores closest to -1 were considered most likely capable of reversing the gene pattern of our query (i.e., overcoming resistance), and were therefore considered the best candidates for functional validation in an attempt to confer Rapamycin sensitivity.

The online database Oncomine (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html) was then used to evaluate Akt expression in primary tissue samples. In Oncomine, data sets are composed of samples represented as microarray data measuring either mRNA expression or DNA copy number on primary tumors, cell lines, or xenografts, generally from published research. These data sets include sample metadata, which is used to set up analyses on groups of interest (cancer vs. normal, etc). These data sets are collected from public repositories, such as GEO and Array Express, and by communicating with study authors, and permit searching for specific disease types, tissue types, and/or genes. Our search was conducted using the filters Akt (gene name) and Lymphoma (disease type).

Cell cycle analysis

Approximately 106 cells of each cell line were harvested (along with untreated controls) after 12 hours of treatment in 12-well plates. Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 400 uL of solution containing propidium iodide and RNAase. Cell cycle was analyzed with a Becton-Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) Flow Cytometer, and proportional cell cycle distribution was assessed with ModFit software.

Protein estimation by Luminex Assay

Approximately 2 × 106 cells were treated (along with untreated controls) for 3 and 6 hours in 12-well plates. Cells were lysed with radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. A commercially-available multiplex panel (Millipore; Billerica, MA) was used to analyze proteins in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway using the manufacturer's recommended technique. Colored bead sets, each of which was coated by the manufacturer with a specific capture antibody, were introduced into 200 uL wells (96-well plates) containing approximately 30 ug of protein. After the sample analyte was captured by the bead, a biotinylated detection antibody was introduced. The mixture was then incubated with Streptavidin-PE conjugate, the reporter molecule, to complete the reaction on the surface of each bead. The beads were passed through dual laser excitation (Luminex 100 Flow Cytometer [Austin, TX]) for identification and quantification. The data was analyzed using Luminex LDS Flow Cytometry Software (v 1.7), with all values calculated as a proportion of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Western blot analysis

After treatment, cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold PBS, and subsequently lysed with RIPA buffer with fresh protease inhibitors. Total protein concentrations were estimated by the Lowry method. Approximately 30 ug of each sample were resolved on tris-glycine gels made in our laboratory, using 15% acrylamide for 4-EBP-1, and 10% acrylamide for all other proteins. These were transferred to nitrocellulose filters, which were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit antibodies against phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP; Ser 235/236; 1:1000), phosphorylated 4EBP-1 (p-4EBP-1; Thr 37/46, 1:1000), phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt; Ser473; 1:250), total Akt (1:250), caspase-3 (1:500), and poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP; 1:500) (all antibodies obtained from Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA). Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit), were incubated for at least one hour at room temperature. Actin was measured with a conjugated HRP antibody. Western blotting luminol reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) was subsequently applied and the membranes were exposed to film for between 10 seconds and one hour. Blot patterns were analyzed using Image-J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), providing a quantitative measure of protein expression.

Assessment of synergy

All determinations of synergism were made using Calcusyn Software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK), based upon the mathematical equations of Chou and Talalay (13). Degrees of synergism are expressed as combination indices (CI), with smallest values indicating the most synergy. CI values <0.8 indicate synergy; those 0.8-1.2 indicate an additive effect; and those >1.2 indicate antagonism.

Results

Gene expression profiling identifies a signature capable of predicting Rapamycin resistance in six DLBCL cell lines

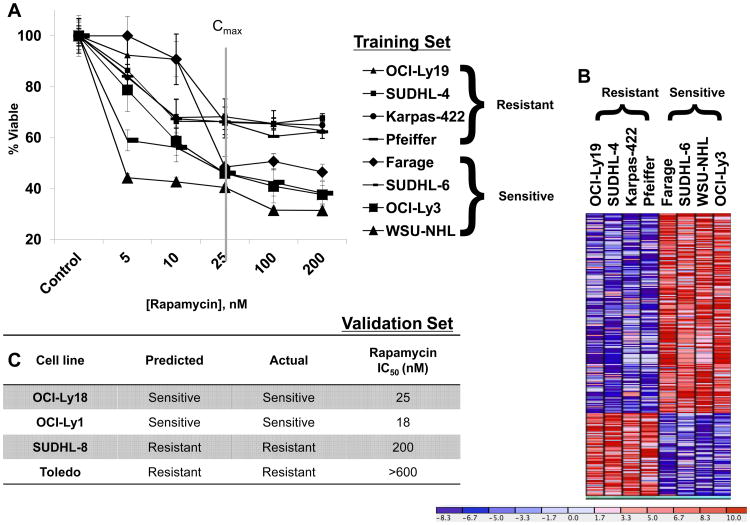

Eight germinal center B-cell (GCB) DLBCL cell lines were treated with Rapamycin in the dose range of 5-200 nM (see Figure 1, Panel A), based upon therapeutically achievable concentrations (14), (15). In our experiments, Rapamycin decreased cell viability by approximately 30 to 60% in the eight cell lines examined, and resulted in stratification into two groups: four cell lines (SUDHL-6, Farage, OCI-Ly3, and WSU-NHL) with IC50 at 25 nM or lower, and the other four (SUDHL-4, OCI-Ly19, and Karpas-422, and Pfeiffer) with IC50 of greater than 200 nM (Figure 1, Panel A). The majority of the cell lines (6/8) have a doubling time between 30-40 hours (16, 17). Accounting for the doubling time of the resistant cell line Karpas (60-90 hours) (16), and sensitive cell line OCI-Ly3 (24 hours) (18), would not change their stratification in our system. We were able to therefore classify these cell lines into two groups based on fluorometric resazurin reduction assay results (see “Methods and Materials”) as a surrogate for cell viability.

Figure 1. Gene expression profiling identifies a signature capable of predicting Rapamycin resistance in DLBCL cell lines.

A. 106 DLBCL cells/ml were treated with Rapamycin, 5-200nM for 48h. DLBCL cell lines corresponding to the dose/response curves are labeled to the right of the figure, in order of degree of resistance. These cell lines comprised the “training” set of our pattern recognition algorithm. The post-treatment cell viability was evaluated by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. The X-axis depicts Rapamycin concentration; the Y-axis, the percentage of viable cells as compared to control. The values of each point represent the mean +/- standard deviation (SD) derived from octuplicate measurements. This was performed thrice for each cell line, with representative results shown. The Cmax in cancer patients, as derived from a phase I trial (15), is indicated by the gray vertical line. B. Using both conventional and modified T-test (see Materials and Methods), a signature of those genes differentially expressed between Rapamycin-sensitive and Rapamycin-resistant cell lines, with significance of p<0.03 was identified. This signature is represented here by a supervised clustering heatmap, as generated by the GenePattern Server. C. The signature shown in Figure 1B was analyzed with the SVM class prediction algorithm found on the GenePattern Server to predict response patterns of six additional cell lines (composing our Validation Set). The predicted and observed response patterns of those cell lines, along with corresponding IC50 levels, are shown.

Global gene expression was measured in the cell lines using the Affymetrix HuGene ST 1.0 Arrays. A heat map representing the 239 significantly (p-value < 0.03) differentially expressed genes between resistant and sensitive cell lines is shown in Figure 1, Panel B. We next examined a multivariable model for resistance based on expression using a linear SVM (see “Methods and Materials”) and the p=239 top univariate candidates. We found that the resistance patterns of four additional DLBCL cell lines, whose IC50 concentrations we determined experimentally, were accurately predicted by our SVM-based classifier (Figure 1, Panel C).

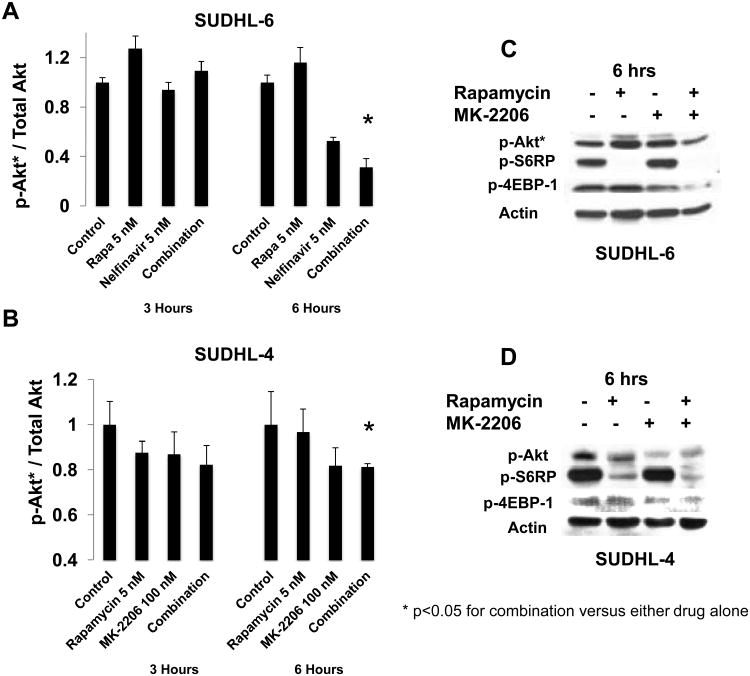

Gene expression profiles of Rapamycin response of DLBCL cell lines identify central role for Akt

To identify pathways and functional groups enriched by differentially-expressed loci, our 239-gene signature (p<0.03) was evaluated with the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis database Core Analysis module (see “Methods and Materials”). The most-enriched Network identified (Network Score = 26, with network functions Hematological System Development and Function, Humoral Immune Response, and Tissue Morphology) revolved around the serine threonine kinase Akt (Figure 2, Panel A). The top two biological functions identified by the Core Analysis were Cancer (Fisher exact test p-value 1.33 × 10-3 - 4.3 × 10-2, with 27 molecules identified) and Hematological Disease (Fisher exact test p-value 1.33 × 10-3 - 3.71 × 10-2, with 10 molecules identified; see Figure 2, Panel B). When the GEP signature was narrowed to include only those genes significantly overexpressed in resistant cell lines, Akt maintained a central position in the most-enriched pathway (Supplementary Figure 1, Panel A).

Figure 2. Gene expression profiles of Rapamycin response of DLBCL cell lines identify central role for Akt.

A-B. The signature shown in Figure 1B was analyzed using the Core Analysis function on the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) Server. A diagram of the top Network enriched by this analysis is shown (A). The most enriched Biological Functions, as determined by IPA Core Analysis of the same signature, are shown in Panel B, with Fisher's exact test p-values as shown. C. The Oncomine database was queried using gene name Akt1, using disease-type filter “Lymphoma.” This provided levels of Akt gene expression levels in healthy B-cells (C: Centroblast; GCB: germinal center B lymphocyte; n=6), Activated B-cell-like DLBCL (ABC-DLBCL; n=26), and GCB-like DLBCL (GCB-DLBCL; n=30) samples of primary (human) tissue samples. These data are represented here as a waterfall plot for each set of samples, in which the Y-axis represents log-2 median-centered ratio, and each sample is displayed in order of this ratio value. D. Protein levels of total Akt, and actin were assayed by Western blotting. Levels of total Akt were quantified as compared to actin (X-axis; measured with ImageJ as described in “Methods and Materials”), and then plotted against the IC50 (Y-axis) for that particular cell line.

We then examined Akt expression in healthy (n=6) and malignant (n=56) primary (human) lymphoid tissue samples using the Oncomine database in order to determine Akt expression in primary NHLs. The data set resulting from our query (as described in “Materials and Methods”) provided normalized expression values of Akt for Activated B-cell-like DLBCL (ABC-DLBCL; n=26); Germinal Cell B-Cell-Like DLBCL (GCB-DLBCL; n=30); and normal B-cells (n=6), each derived from a study describing GEPs characteristic of GCB- and ABC-DLBCL (19). Akt mRNA was relatively over-expressed in DLBCL as compared to normal lymphoid tissue, with approximately two-thirds of all samples showing relative over-expression of this gene (Figure 2, Panel C).

Higher phospho-Akt (p-Akt) protein levels are associated with poor prognosis in DLBCL (20) and other malignancies (21), (22). We therefore asked the question whether Akt levels, as determined by Western blotting, would correlate with resistance to Rapamycin in DLBCL cell lines. We found evidence of a loose correlation between total Akt and IC50 for the eight cell lines tested (Figure 2, Panel D; source Western blots shown in Supplementary Figure 1, Panel B). However, we also found that higher levels of p-Akt (Supplementary Figure 1, Panel C), including as a proportion of total Akt (Supplementary Figure 1, Panel D), inversely correlated with IC50, such that sensitive cell lines had overall higher levels of p-Akt.

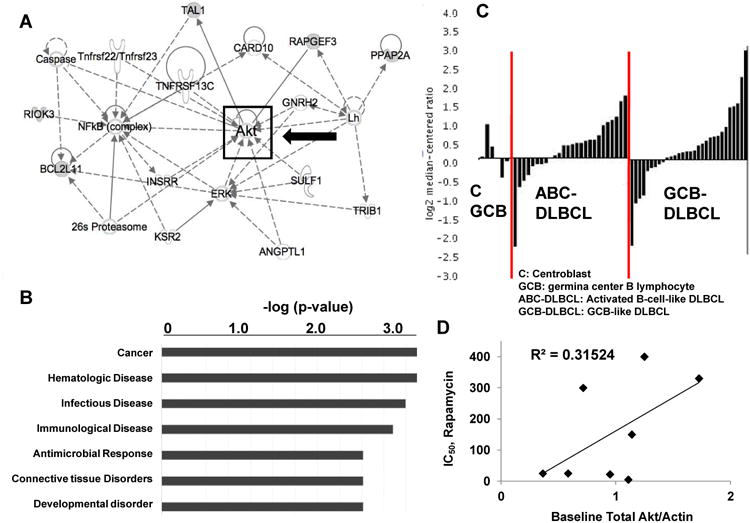

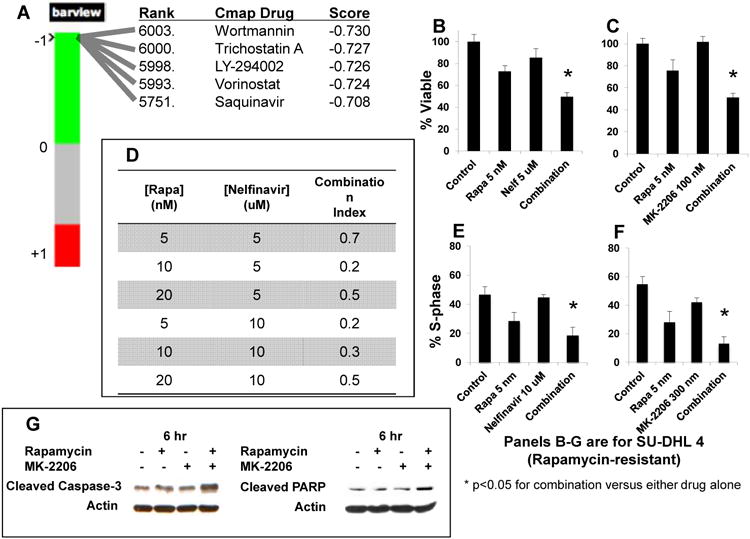

Connectivity mapping identifies Akt inhibitors that synergize with Rapamycin at clinically relevant doses

In light of A) the relatively low response rates of DLBCL patients seen in trials of mTOR inhibitors (7, 23); and B) the fact that data mining of gene expression profiles can identify novel drugs capable of overcoming chemotherapy resistance (24), we next sought to use GEP data for in silico identification of drugs most likely to overcome resistance to mTOR inhibitors. Connectivity mapping of differentially-expressed genes between Rapamycin sensitive and resistant cell lines (see “Materials and Methods”), provided a ranked list of candidate compounds in order of likelihood of efficacy for reversing the GEP-associated resistance. In this list, two phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors (Wortmannin and LY294002), the protease inhibitor (PI) Saquinavir, and multiple histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (including both Vorinostat and Trichostatin-A), were all identified within the top 2% of the candidate compounds (Figure 3, Panel A).

Figure 3. Connectivity mapping can identify compounds targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway, which synergize with Rapamycin at clinically relevant doses.

A. The signature of differentially-expressed genes was submitted for analysis to the Connectivity map (Cmap) server. Shown here are the rank, name, and Cmap score of selected compounds, each within the top 2% of perturbagens, as determined by analysis of this signature. B-C. 106 cells/ml of two Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) and two Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) DLBCL cells were treated with Rapamycin, an Akt inhibitor (either Nelfinavir or MK-2206), and the combination of Rapamycin and an Akt inhibitor, for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated twice, with representative results shown. Viability patterns of the Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4 treated with Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (Nelf) (B), and Rapamycin and MK-2206 (C), are shown. The Y-axis represents percentage of cells viable. D. Combination indices (CI) values were calculated using the Chou-Talalay equation, as employed by Calcusyn software, for the four cell lines described above (SUDHL-6, WSU-NHL, SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19). Shown here are the CI values observed in the SUDHL-4 cell line. Similar results, indicative of synergy, were achieved in the other three cell lines. E-F. 106 cells/ml of the same four DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL-6, WSU-NHL, SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) were treated for 12 hours with Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (Nelf) (E), and Rapamycin and MK-2206 (F), and then analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide. Each experiment was repeated twice under independent conditions, with representative results shown. The proportion of cells in each treatment group found to be in S-phase is shown as a marker of cell cycle progression. The Y-axis represents percentage of cells in S-phase. G. Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) were treated for 6 hours with Rapamycin at 25 nM, MK-2206 at 300 nM, and the combination, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of cleaved caspase 3 (left) and cleaved PARP (right), in the SUDHL-4 cell line.

While PI3K and HDAC inhibition have been previously described to synergize with mTOR inhibitors (25, 26), we reasoned that inhibition of Akt would represent a novel strategy to augment therapeutic activity of mTOR inhibition in DLBCL. We elected to investigate Akt inhibition with two agents: MK-2206, a highly selective allosteric inhibitor of Akt; and Nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor used frequently for treatment of HIV. MK-2206 was chosen for its target specificity, and because there are safety and efficacy data in humans (27). Nelfinavir was chosen because A) of preclinical evidence showing that it inhibits activity of Akt (28); B) it has the most potent anti-tumor activity among its class of drug (including Saquinivir) (29); C) as an FDA-approved medication, it has ample pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) and safety data. We compared the synergy (with Rapamycin) in anti-lymphoma effects between the specific Akt inhibitor MK-2206, and the PI Nelfinavir, which likely inhibits Akt through an indirect mechanism (28), by assaying cell viability, cell cycle changes and inhibition of downstream genes in the AKT/mTOR pathway in DLBCL cell lines. We also studied the effect of combining Rapamycin with MK-2206 on the viability of two breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB 231 and MDA-MB-468, in order to help determine whether the combination effects were specific to lymphoma cell lines. Then, in order to help validate the predictive accuracy of connectivity mapping, we sought a commonly used cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent predicted by our connectivity mapping results to be unlikely to overcome Rapamycin resistance. In this manner, we identified the agent Vinblastine, a microtubule disruptive agent used in lymphoid malignancies and solid tumors, for further testing in combination with Rapamycin.

We found that Rapamycin showed synergistic effects with Nelfinavir in inhibiting cell viability in Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4, Figure 3, Panel B) as well as Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6, Supplementary Figure 2, Panel A). Combination index (CI) values <1 were demonstrable in four cell lines tested (SUDHL-4 [shown in Figure 3, Panel D], SUDHL-6, OCI-Ly19, and WSU-NHL). Rapamycin also demonstrated synergistic effects on cell viability when used with MK-2206 (Figure 3, Panel C). CI values <1 were again demonstrable for each cell line (SUDHL-4, SUDHL-6, OCI-Ly19, and WSU-NHL) when treated with Rapamycin and MK-2206 (Supplementary Figure 2, Panel B). Taken together, our data indicate that Rapamycin synergizes effectively with both Nelfinavir and MK-2206 in a panel of four DLBCL cell lines, including two (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) that we previously classified as resistant to Rapamycin as a single agent (see Figure 1, Panel A). Significant synergy was observed with combining Rapamycin and MK-2206 in breast cancer cell lines (Supplementary Figure 5), suggesting that the therapeutic effects of dual targeting of mTOR and Akt are not limited to lymphoma cell lines. We also found that the combinations of Rapamycin with Vinblastine in SUDHL 4 and SUDHL 6 cell lines were not synergistic, and in fact antagonistic, with CI values >1 (Supplementary Figures 6), suggesting that connectivity mapping can predict for both the presence and absence of synergism.

To investigate the mechanism of synergy, we next examined effects of these agents on cell cycle and apoptosis. To evaluate cell cycle effects, cells were treated with individual agents and combinations, then analyzed cell cycle phase distributions by flow cytometry (see “Materials and Methods”). The combinations of Rapamycin and Nelfinavir, and Rapamycin and MK-2206, produced greater reduction in proportion of cells in S phase than when any single drug was used alone. This phenomenon was demonstrable in both Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (Figure 3, Panels E and F; Supplementary Figure 2, Panels C and D) and Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (Supplementary Figure 2, Panels E and F). We next evaluated caspase-3 and PARP cleavage as markers of apoptosis. We found that, in SUDHL-4 cells, levels of cleaved forms of both proteins were increased by the combination of Rapamycin and MK-2206 as compared to control and/or either drug alone (Figure 3, Panel G). Nelfinavir also increased the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP compared to control, although these levels were not further decreased in the combination of Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (Supplementary Figure 3, Panel A).

Akt activation is induced by Rapamycin treatment; this activation is abrogated by Akt inhibitors

In light of data suggesting that Rapamycin treatment can induce Akt phosphorylation via a TORC2-mediated feedback mechanism in DLBCL (25), we examined whether this phenomenon could be abrogated in DLBCL cell lines by Akt inhibitors MK-2206 and Nelfinavir. Using a flow cytometry-based multiplex assay for Akt/mTOR pathway proteins, we found increased p-Akt levels in the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line SUDHL-6, but not in the Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4, after short exposure to Rapamycin (Figure 4, Panel A). Furthermore, the use of either Nelfinavir or MK-2206 decreased levels of phosphorylated Akt, even in the presence of Rapamycin, particularly after 6 hours of exposure (Figure 4, Panels A and B).

Figure 4. Akt activation is induced by Rapamycin treatment, and Akt inhibitors abrogate Rapamycin-induced Akt activation.

A-B. 106 cells/ml of the same four DLBCL cell lines (SUDHL-6, WSU-NHL, SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) were treated with Rapamycin, an Akt inhibitor (either Nelfinavir or MK-2206), and the combination of Rapamycin and Akt inhibitor for 3h and 6h. A flow-cytometry-based multiplex protein assay of phosphorylated Akt, as a proportion of total Akt, was performed in SUDHL-6 (Rapamycin-sensitive) cells treated with Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (A) and SU-DHL 4 (Rapamycin-resistant) cells treated with Rapamycin and MK-2206 (B). Each experiment was performed in triplicate, in independent conditions, with mean and SD displayed. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (t-test p value <0.05). C-D. One Rapamycin-resistant cell line (SUDHL-4) and one Rapamycin-sensitive cell line (SUDHL-6) were treated for 6 hours with Rapamycin (25 nM), Nelfinavir (15 uM), and the combination; or Rapamycin (25 nM), MK-2206 (300 nM), and the combination; after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phospho-S-6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP), and phosphorylated 4-EBP-1 (p-4-EBP-1) in SUDHL-6 cells (C), and SUDHL-4 cells (D) treated with Rapamycin (5 nM) and MK-2206 (100 nM) for 6 hours.

We sought to confirm these findings with immunoblotting, and indeed found that Rapamycin induced Akt activation in Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (though not clearly in Rapamycin-resistant cell lines), and that the combination of Rapamycin with either MK-2206 (Figure 4, Panels C and D; Supplementary Figure 3, Panels B and C) or Nelfinavir (Supplementary Figure 4, Panels A-C) led to a significant decrease in the levels of p-Akt relative to Rapamycin treatment alone. Importantly, neither Nelfinavir nor MK-2206 negatively affected Rapamycin-induced inhibition of phosphorylation of mTOR targets S6 ribosomal protein (S6RP) and translational cofactor 4-EBP-1.

mTOR inhibition and Akt inhibition synergize with cytotoxic chemotherapy in DLBCL

We next asked the question whether mTOR inhibitors and Akt inhibitors would synergize with chemotherapy used in DLBCL. To do so, we evaluated the effects of Doxorubicin, a potent cytotoxic anti-lymphoma agent, in combination with Rapamycin and MK-2206. Using each agent at concentrations achievable in humans, with treatment for 48 hours, we found that both Rapamycin and MK-2206 synergize with Doxorubicin in reduction of cell viability (Supplementary Figure 7, Panels A and B). The three-drug combination indices for Doxorubicin, Rapamycin, and MK-2206 were well below 0.8, signifying mathematical confirmation of synergy (Supplementary Figure 7, Panel C) in all four cell lines studied (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19 [Rapamycin-resistant]; SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL [Rapamycin-sensitive]).

Discussion

In summary, we show here that gene expression profiling has the ability to predict resistance to Rapamycin, in which the expression of Akt is central. We subsequently identify agents that inhibit Akt and synergize with mTOR inhibitors (such as Rapamycin) in reduction of viability, inhibition of cell cycle progression, and promotion of apoptosis. Our data suggest that simultaneous mTOR and Akt inhibition is an effective strategy to substantiate Rapamycin cytotoxicity in both Rapamycin-sensitive and –resistant DLBCL cell lines

Gene expression signatures that sub-classify DLBCL and predict response to chemoimmunotherapy have been described (30). The accurate stratification of cell line responses to Rapamycin by GEP supports further testing of this signature in future clinical trials of mTOR inhibitors in DLBCL. Notably, cDNA-mediated Annealing, Selection, extension, and Ligation (DASL) technology (31)(32) may allow use of paraffin embedded tissues to obtain genomic expression data, which would circumvent the need to obtain fresh frozen samples from patients. We believe that our data represents a framework for a technique that could offer early and precise prediction of response to mTOR inhibitors, and should permit better selection of patients for treatment using these agents.

After confirming that connectivity mapping could positively predict for the presence of synergy, we felt it was warranted to determine if it could predict the opposite (ie, for the lack of synergy). We therefore identified Vinblastine as an agent predicted not to have synergistic properties with Rapamycin, and experimentally demonstrated antagonistic effects upon cell viability. Similar results were obtained for Metformin, another pharmacologic agent predicted to be devoid of synergistic effect when combined with Rapamycin (data not shown).

High levels of tissue Akt phosphorylation have been associated with inferior clinical outcomes in breast cancer (21), lung cancer (22), and DLBCL (20), though none of these studies included patients treated with mTOR inhibitors. Some authors have associated increased Akt activation with increased sensitivity to mTOR inhibition (33), (34, 35), and our data demonstrating increased phosphorylated Akt in sensitive cell lines would certainly support this. However, others have observed mTOR inhibitor resistance in tumors with PI3K/Akt activation: in a phase I trial of patients with PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on Chromosome 10)-deficient glioblastoma treated with Rapamycin, baseline Akt upregulation was associated with a significantly shorter time to progression (36). Taken together, these data indicate that the ability of p-Akt levels to predict mTOR inhibitor resistance might be tumor-dependent, and should be further investigated in future trials.

Other recent preclinical and clinical findings support the idea that inhibiting proteins upstream or downstream of mTOR in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway can overcome mTOR inhibitor resistance. Simultaneous Akt/PI3K and mTOR inhibition by the novel agent NVP-BEZ235 showed nanomolar efficacy in Rapamycin-resistant Primary Effusion Lymphoma cell lines (37); and the Akt/PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was efficacious in multiple DLBCL cell lines. In this study, however, elevated p-Akt levels predicted for increased resistance to LY294002, suggesting that targeting of both Akt and PI3K might allow for the greatest therapeutic efficacy. Gupta and colleagues demonstrated that phosphorylated Akt was upregulated by mTOR inhibitor treatment in DLBCL cell lines and patients, and that treatment with histone deacetylase inhibition overcame this effect and synergized with mTOR inhibition (25). In our experiments, treatment of DLBCL cells with Rapamycin alone did not produce apoptosis, consistent with the results reported by Gupta, et al and others (38). However, the baseline cleavage of Caspase-3 and PARP was significantly increased upon combination of the Akt inhibitors. Our data support a novel strategy for inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by synergistic application of Akt inhibitors, along with Rapamycin, the prototypical mTOR inhibitor. In addition, our data indicates that the phosphorylation of Akt is a dynamic and reactive process in DLBCL, and can be modulated with therapeutic benefit by the use of Akt inhibitors.

We chose to target Akt with MK-2206, as it has been shown to inhibit activation of all three isoforms of Akt at nanomolar doses and synergize with cytotoxic and targeted chemotherapy agents in preclinical models (39). Based upon preclinical data and xenograft models, MK-2206 is known to be highly selective for Akt1 and Akt 2 over other members of the AGC family of kinases, inhibition of which required MK-2206 concentrations >50uM (40). We therefore believe that all concentrations of MK-2206 used in our experimentation would have maintained a high level of specificity for Akt, and that desired pharmacologic effects were primarily due to Akt inhibition, as opposed to off-target effects. Most importantly, MK-2206 has shown safety and efficacy in early phase human trials (27). We believe that the demonstration of synergism between Rapamycin and MK-2206 is a significant step in its optimal deployment in future clinical trials.

Protease inhibitors (PIs), a class of anti-retroviral agents used widely in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), have been shown to effectively downregulate Akt phosphorylation by inhibiting proteasome activity and inducing the unfolded protein response, which in turn leads to a global decrease in protein synthesis (14). Nelfinavir, a PI that is FDA-approved for use in HIV/AIDS, can sensitize malignant cells to both chemotherapy (41) and radiation (42). Of six clinically relevant PIs tested in the NCI-60 panel of cancer cell lines, Nelfinavir demonstrated the most potent effects in decreasing viability of this panel of cancer cell lines (29). It has also been noted that the PI3K/Akt pathway is up-regulated in HIV-related malignancies associated with Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and Kaposi Sarcoma Herpes Virus (KSHV) (43), and this has formed the rationale for successful testing of inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in preclinical models of these tumors (37). The lifetime incidence of NHL is dramatically increased in patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and DLBCLs comprise the vast majority of histologic subtypes of these AIDS-related lymphomas (ARL) (44). Patients with HIV/AIDS are widely excluded from participation in clinical trials of antineoplastic agents, and data for the optimal treatment of ARL are therefore lacking. Advances in the safe and effective treatment of ARL, including therapy aimed at HIV itself, are therefore urgently needed. We believe that our data, showing the presence and mechanism of synergy between Nelfinavir and Rapamycin, support the potential for Nelfinavir to be used in clinical trials for the treatment of ARL, and perhaps other AIDS-related malignancies as well. Because both Rapamycin and Nelfinavir are FDA-approved compounds, their use is supported by significant safety and efficacy data, and repositioning them as antineoplastic agents (alone or in combination) is significantly faster than bringing new compounds to market (15). Likewise, safety data for the use of MK-2206 in humans are already reported, facilitating its investigation in clinical trials, particularly as compared to other compounds yet to be tested beyond the laboratory.

Our data suggest that exposure to the mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin seemed to up-regulate expression of phosphorylated Akt in sensitive cell lines, but not necessarily in resistant cell lines. This is consistent with the notion that mTOR inhibitors induce greater perturbation of cellular function in sensitive cell lines as compared to resistant cell lines. But this also suggests that resistant cell lines may have additional mechanisms of resistance to mTOR inhibition, which is unlikely to be explained simply by studying levels of one isoform of p-Akt. Rather, resistance may be related to either qualitative differences in p-Akt (eg, phosphorylation at sites other than Serine 473), or variation in the quantity or quality of other molecules in the Akt/mTOR pathway, which would only be captured with wider pathway-based or genomic studies (such as of our 239- gene profile). Regardless of the actual explanation for these observed differences, we view the in silico identification of agents that can ultimately synergize with Rapamycin, in both Rapamycin-sensitive and Rapamycin-resistant cell lines, to be an important finding of this work.

In conclusion, our results identify a GEP based signature for predicting response to Rapamycin in DLBCL and support Akt inhibition as a viable strategy for producing synergistic anti-lymphoma cytotoxicity with mTOR inhibition. More broadly, our approach supports the use of global RNA expression and drug discovery using connectivity mapping to identify synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy, and to improve the selection of appropriate patients.

Supplementary Material

A. Using the Core Analysis function on the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) Server, a gene signature of only those genes over-expressed by Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (p<0.03) was analyzed. A schematic diagram of the top pathway enriched by this analysis is shown.

B. Untreated cell lysates of eight cell lines (those used to determine GEP signature associated with Rapamycin resistance) were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), Total Akt, and actin.

C-D. Protein levels of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), total Akt, and actin were assayed by Western blotting. Levels of phosphorylated and total Akt were quantified, respectively, as proportions of actin (X-axis; measured with ImageJ as described in “Methods and Materials”), and then plotted against the IC50 (Y-axis) for that particular cell line.

A. Approximately 106 cells/ml of two Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) and two Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) DLBCL cells were treated with Rapamycin, an Akt inhibitor, either Nelfinavir or MK-2206, and the combination of Rapamycin and an Akt inhibitor, for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated twice. Shown here are representative results for the Rapamycin-sensitive SUDHL-6 cell line after 48 hours of treatment with Rapamycin (Rapa), Nelfinavir (Nelf), and the combination.

B. Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19), and Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) were treated with the combination of Rapamycin and MK-2206 for 48h, as described above. Combination indices for the effects on viability, as determined using the Chou-Talalay equation, are shown.

C-F. DLBCL cell lines were treated for 12 hours with Rapamycin and MK-2206 (C and E), and Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (D and F), and then analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide. Each experiment was repeated twice under independent conditions, with representative results shown. Cell cycle progression, as represented by proportion of cells in S-phase, in the Rapamycin-resistant cell line OCI-Ly19 (C and D), and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line SUDHL-6 (E and F) are shown.

A. Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4 was treated for 6 hours with Rapamycin at 25 nM, MK-2206 at 300 nM, and the combination, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP.

B-C. The Rapamycin-resistant cell line OCI-Ly19 (B) and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line WSU-NHL (C) were treated for 3 and 6 hours with Rapamycin, MK-2206, and the combination, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Shown here are results using antibodies against phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phospho-S-6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP), and phosphorylated 4-EBP-1 (p-4EBP-1). Experiments were performed in duplicate, with representative results shown.

A-C. The Rapamycin-resistant cell lines OCI-Ly19 (A) and SUDHL-4 (C) and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line WSU-NHL (B) were treated for 3 hours and 6 hours with Rapamycin, Nelfinavir, and the combination of the two agents, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Shown here are results using antibodies against phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phospho-S-6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP), and phosphorylated 4-EBP-1 (p-4EBP-1).

A-B. Shown here are normalized isobolograms of treatment effects of Rapamycin and MK-2206, in the above cell lines. Proportion of MK-2206 IC50 is shown on the X-axis, and proportion of Rapamycin IC50 are shown on the Y-axis. Points at or near the red line are indicative of additive effects of the two agents; those below the line are indicative of synergistic effects.

A-B. Approximately 106 cells/ml of SUDHL-4 and SUDHL-6 were treated with Rapamycin, Vinblastine, and the combination of both drugs (all doses lower than IC50 for each drug), for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated twice. Shown here are representative results.

C-D. Combination indices for the effects of combination of Rapamycin and Vinblastine on viability, as determined using the Chou-Talalay equation, are shown.

A-B. 106 cells/ml of two Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) and two Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) DLBCL cells were treated with single-agent Rapamycin, MK-2206, and Doxorubicin; the combination of Rapamycin and Doxorubicin; and the combination of MK-2206 and Doxorubicin, each for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated once, with representative results shown. Shown here are normalized isobolograms of treatment effects of Rapamycin and Doxorubicin (A), and MK-2206 and Doxorubicin (B), in the Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4. Proportion of Doxorubicin IC50 is shown on the X-axis, and proportion of Rapamycin IC50 and MK-2206 IC50, respectively, are shown on the Y-axes. Points at or near the red line are indicative of additive effects of the two agents; those below the line are indicative of synergistic effects.

C. Rapamycin-resistant (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) and Rapamycin-sensitive (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) were treated with the combination of three agents (Rapamycin, MK-2206, and Doxorubicin) for 48h as described above, and viability was assessed. Combination indices (CI) for the treatment effect were calculated using the Chou-Talalay equation (see Methods and Materials), and are shown here. CI Values below 0.8 indicate the presence of synergistic effect.

Statement of Translational Relevance.

There is a large unmet need for advances in the treatment of relapsed and refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). Recent trials of mTOR inhibitors (mTORi) in this population have shown low response rates, and mechanisms of resistance are poorly described for these drugs. We have identified a gene expression signature that proved to be an accurate biomarker for predicting response to Rapamycin in DLBCL cell lines. Using a systems biology approach consisting of pathway analysis and connectivity mapping, we next identified Akt inhibitors MK-2206 and Nelfinavir capable of overcoming resistance to Rapamycin. These findings create a basis for combining these agents with Rapamycin in clinical trials for lymphoma patients and support the use of gene expression profiles for patient selection for mTOR inhibitor therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Barbara Birshtein, PhD, for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Hoskins P, et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hess G, Herbrecht R, Romaguera J, Verhoef G, Crump M, Gisselbrecht C, et al. Phase III study to evaluate temsirolimus compared with investigator's choice therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3822–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess G, Smith SM, Berkenblit A, Coiffier B. Temsirolimus in mantle cell lymphoma and other non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):S37–45. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sehgal SN. Rapamune (Sirolimus, rapamycin): an overview and mechanism of action. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 1995;17:660–5. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199512000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SM, van Besien K, Karrison T, Dancey J, McLaughlin P, Younes A, et al. Temsirolimus has activity in non-mantle cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtypes: The University of Chicago phase II consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4740–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witzig TE, Reeder CB, Laplant BR, Gupta M, Johnston PB, Micallef IN, et al. A phase II trial of the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. Leukemia. 2010 doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riedel RF, Porrello A, Pontzer E, Chenette EJ, Hsu DS, Balakumaran B, et al. A genomic approach to identify molecular pathways associated with chemotherapy resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3141–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iqbal J, Liu Z, Deffenbacher K, Chan WC. Gene expression profiling in lymphoma diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2009;22:191–210. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Wiestner A, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, et al. The proliferation gene expression signature is a quantitative integrator of oncogenic events that predicts survival in mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:185–97. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth G. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3:1–26. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth G. Limma: linear models for microarray data. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. 2005:397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Advances in Enzyme Regulation. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman JJ, Kahan BD. Pharmacokinetics of sirolimus in stable renal transplant patients after multiple oral dose administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:405–15. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jimeno A, Rudek MA, Kulesza P, Ma WW, Wheelhouse J, Howard A, et al. Pharmacodynamic-guided modified continuous reassessment method-based, dose-finding study of rapamycin in adult patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4172–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DSMZ. [cited 2011 May 30]; Available from: http://www.dsmz.de/human_and_animal_cell_lines/

- 17.ATCC. cited; Available from: http://www.atcc.org/

- 18.Tweeddale ME, Lim B, Jamal N, Robinson J, Zalcberg J, Lockwood G, et al. The presence of clonogenic cells in high-grade malignant lymphoma: a prognostic factor. Blood. 1987;69:1307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uddin S, Hussain AR, Siraj AK, Manogaran PS, Al-Jomah NA, Moorji A, et al. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/AKT pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survival. Blood. 2006;108:4178–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou X, Tan M, Stone Hawthorne V, Klos KS, Lan KH, Yang Y, et al. Activation of the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin/4E-BP1 pathway by ErbB2 overexpression predicts tumor progression in breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6779–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David O, Jett J, LeBeau H, Dy G, Hughes J, Friedman M, et al. Phospho-Akt overexpression in non-small cell lung cancer confers significant stage-independent survival disadvantage. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6865–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SM, van Besien K, Karrison T, Dancey J, McLaughlin P, Younes A, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2010. Temsirolimus Has Activity in Non-Mantle Cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Subtypes: The University of Chicago Phase II Consortium. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006;313:1929–35. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta M, Ansell SM, Novak AJ, Kumar S, Kaufmann SH, Witzig TE. Inhibition of histone deacetylase overcomes rapamycin-mediated resistance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by inhibiting Akt signaling through mTORC2. Blood. 2009;114:2926–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sos ML, Fischer S, Ullrich R, Peifer M, Heuckmann JM, Koker M, et al. Identifying genotype-dependent efficacy of single and combined PI3K- and MAPK-pathway inhibition in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18351–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907325106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolcher AW, Yap I, Fearen A. A phase I study of MK-2206, an oral potent allosteric Akt inhibitor (Akti), in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumor (ST) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 abstract 3503. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta AK, Li B, Cerniglia GJ, Ahmed MS, Hahn SM, Maity A. The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir downregulates Akt phosphorylation by inhibiting proteasomal activity and inducing the unfolded protein response. Neoplasia. 2007;9:271–8. doi: 10.1593/neo.07124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, Shoemaker RH, Best CJM, Abu-Asab MS, et al. Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5183–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenz G, Wright G, Dave SS, Xiao W, Powell J, Zhao H, et al. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2313–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abramovitz M, Ordanic-Kodani M, Wang Y, Li Z, Catzavelos C, Bouzyk M, et al. Optimization of RNA extraction from FFPE tissues for expression profiling in the DASL assay. Biotechniques. 2008;44:417–23. doi: 10.2144/000112703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.April C, Klotzle B, Royce T, Wickham-Garcia E, Boyaniwsky T, Izzo J, et al. Whole-genome gene expression profiling of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macaskill EJ, Bartlett JM, Sabine VS, Faratian D, Renshaw L, White S, et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in early breast cancer: results of a pre-operative study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0967-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, Malina A, Ray S, Kogan S, et al. Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nature. 2004;428:332–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beeram M, Tan QTN, Tekmal RR, Russell D, Middleton A, DeGraffenried LA. Akt-induced endocrine therapy resistance is reversed by inhibition of mTOR signaling. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1323–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, Brown K, Dang J, Zhu S, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhatt AP, Bhende PM, Sin SH, Roy D, Dittmer DP, Damania B. Dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR inhibits autocrine and paracrine proliferative loops in PI3K/Akt/mTOR-addicted lymphomas. Blood. 2010;115:4455–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanner K, Hipp S, Oelsner M, Ringshausen I, Bogner C, Peschel C, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition induces cell cycle arrest in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells and sensitises DLBCL cells to rituximab. British Journal of Haematology. 2006:475–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirai H, Sootome H, Nakatsuru Y, Miyama K, Taguchi S, Tsujioka K, et al. MK-2206, an allosteric Akt inhibitor, enhances antitumor efficacy by standard chemotherapeutic agents or molecular targeted drugs in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1956–67. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bilodeau MT, Balitza AE, Hoffman JM, Manley PJ, Barnett SF, Defeo-Jones D, et al. Allosteric inhibitors of Akt1 and Akt2: a naphthyridinone with efficacy in an A2780 tumor xenograft model. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Ikezoe T, Nishioka C, Bandobashi K, Takeuchi T, Adachi Y, et al. NFV, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor, induces growth arrest, reduced Akt signalling, apoptosis and docetaxel sensitisation in NSCLC cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1653–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plastaras JP, Vapiwala N, Ahmed MS, Gudonis D, Cerniglia GJ, Feldman MD, et al. Validation and toxicity of PI3K/Akt pathway inhibition by HIV protease inhibitors in humans. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:628–35. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.5.5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Damania B. In: Molecular Basis for Therapy of AIDS-Defining Cancers. Dittmer DP, Krown SE, editors. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navarro WH, Kaplan LD. AIDS-related lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2006;107:13–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Using the Core Analysis function on the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) Server, a gene signature of only those genes over-expressed by Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (p<0.03) was analyzed. A schematic diagram of the top pathway enriched by this analysis is shown.

B. Untreated cell lysates of eight cell lines (those used to determine GEP signature associated with Rapamycin resistance) were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), Total Akt, and actin.

C-D. Protein levels of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), total Akt, and actin were assayed by Western blotting. Levels of phosphorylated and total Akt were quantified, respectively, as proportions of actin (X-axis; measured with ImageJ as described in “Methods and Materials”), and then plotted against the IC50 (Y-axis) for that particular cell line.

A. Approximately 106 cells/ml of two Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) and two Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) DLBCL cells were treated with Rapamycin, an Akt inhibitor, either Nelfinavir or MK-2206, and the combination of Rapamycin and an Akt inhibitor, for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated twice. Shown here are representative results for the Rapamycin-sensitive SUDHL-6 cell line after 48 hours of treatment with Rapamycin (Rapa), Nelfinavir (Nelf), and the combination.

B. Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19), and Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) were treated with the combination of Rapamycin and MK-2206 for 48h, as described above. Combination indices for the effects on viability, as determined using the Chou-Talalay equation, are shown.

C-F. DLBCL cell lines were treated for 12 hours with Rapamycin and MK-2206 (C and E), and Rapamycin and Nelfinavir (D and F), and then analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide. Each experiment was repeated twice under independent conditions, with representative results shown. Cell cycle progression, as represented by proportion of cells in S-phase, in the Rapamycin-resistant cell line OCI-Ly19 (C and D), and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line SUDHL-6 (E and F) are shown.

A. Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4 was treated for 6 hours with Rapamycin at 25 nM, MK-2206 at 300 nM, and the combination, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Each experiment was repeated, with representative results provided. Shown here are results from analysis of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP.

B-C. The Rapamycin-resistant cell line OCI-Ly19 (B) and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line WSU-NHL (C) were treated for 3 and 6 hours with Rapamycin, MK-2206, and the combination, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Shown here are results using antibodies against phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phospho-S-6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP), and phosphorylated 4-EBP-1 (p-4EBP-1). Experiments were performed in duplicate, with representative results shown.

A-C. The Rapamycin-resistant cell lines OCI-Ly19 (A) and SUDHL-4 (C) and the Rapamycin-sensitive cell line WSU-NHL (B) were treated for 3 hours and 6 hours with Rapamycin, Nelfinavir, and the combination of the two agents, after which cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot technique. Shown here are results using antibodies against phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), phospho-S-6 ribosomal protein (p-S6RP), and phosphorylated 4-EBP-1 (p-4EBP-1).

A-B. Shown here are normalized isobolograms of treatment effects of Rapamycin and MK-2206, in the above cell lines. Proportion of MK-2206 IC50 is shown on the X-axis, and proportion of Rapamycin IC50 are shown on the Y-axis. Points at or near the red line are indicative of additive effects of the two agents; those below the line are indicative of synergistic effects.

A-B. Approximately 106 cells/ml of SUDHL-4 and SUDHL-6 were treated with Rapamycin, Vinblastine, and the combination of both drugs (all doses lower than IC50 for each drug), for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated twice. Shown here are representative results.

C-D. Combination indices for the effects of combination of Rapamycin and Vinblastine on viability, as determined using the Chou-Talalay equation, are shown.

A-B. 106 cells/ml of two Rapamycin-sensitive cell lines (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) and two Rapamycin-resistant cell lines (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) DLBCL cells were treated with single-agent Rapamycin, MK-2206, and Doxorubicin; the combination of Rapamycin and Doxorubicin; and the combination of MK-2206 and Doxorubicin, each for 48h. Viability was assessed by a fluorometric resazurin reduction assay. Each experiment was performed in octuplicate, and repeated once, with representative results shown. Shown here are normalized isobolograms of treatment effects of Rapamycin and Doxorubicin (A), and MK-2206 and Doxorubicin (B), in the Rapamycin-resistant cell line SUDHL-4. Proportion of Doxorubicin IC50 is shown on the X-axis, and proportion of Rapamycin IC50 and MK-2206 IC50, respectively, are shown on the Y-axes. Points at or near the red line are indicative of additive effects of the two agents; those below the line are indicative of synergistic effects.

C. Rapamycin-resistant (SUDHL-4 and OCI-Ly19) and Rapamycin-sensitive (SUDHL-6 and WSU-NHL) were treated with the combination of three agents (Rapamycin, MK-2206, and Doxorubicin) for 48h as described above, and viability was assessed. Combination indices (CI) for the treatment effect were calculated using the Chou-Talalay equation (see Methods and Materials), and are shown here. CI Values below 0.8 indicate the presence of synergistic effect.