Abstract

Objective

To examine and quantify the relation between purine intake and the risk of recurrent gout attacks among gout patients.

Methods

The authors conducted a case-crossover study to examine associations of a set of putative risk factors with recurrent gout attacks. Individuals with gout were prospectively recruited and followed online for 1 year. Participants were asked about the following information when experiencing a gout attack: the onset date of the gout attack, clinical symptoms and signs, medications (including antigout medications), and presence of potential risk factors (including daily intake of various purine-containing food items) during the 2-day period prior to the gout attack. The same exposure information was also assessed over 2-day control periods.

Results

This study included 633 participants with gout. Compared with the lowest quintile of total purine intake over a 2-day period, OR of recurrent gout attacks were 1.17, 1.38, 2.21 and 4.76, respectively, with each increasing quintile (p for trend <0.001). The corresponding OR were 1.42, 1.34, 1.77 and 2.41 for increasing quintiles of purine intake from animal sources (p for trend <0.001), and 1.12, 0.99, 1.32 and 1.39 from plant sources (p=0.04), respectively. The effect of purine intake persisted across subgroups by sex, use of alcohol, diuretics, allopurinol, NSAIDs and colchicine.

Conclusions

The study findings suggest that acute purine intake increases the risk of recurrent gout attacks by almost fivefold among gout patients. Avoiding or reducing amount of purine-rich foods intake, especially of animal origin, may help reduce the risk of gout attacks.

INTRODUCTION

Gout is a common and excruciatingly painful inflammatory arthritis caused by monosodium crystal deposition. While the pathophysiology of gout is well understood and efficacious pharmacological regimens are available, the disease burden of gout remains substantial and is growing.1 In addition, many patients with gout continue to experience recurrent gout attacks.2,3 Gout attacks are frequently ascribed to triggering events such as high-purine food intake, and avoidance of these triggers is widely promulgated as a central strategy in the management of gout. Despite the widespread adoption of such strategies, the risk that purine intake confers on gout recurrence remains unknown.

Purine intake is associated with hyperuricaemia4 and an increased risk of incident gout.5 While recognised anecdotally to trigger gout attacks, no study to date has examined whether purine-rich food intake triggers recurrent gout attacks over a short period of time. Clarifying this link and quantifying its magnitude would help gout patients make informed decisions about food items that should be limited or avoided, or even certain items that may be preferred to help lower their risk of recurrent gout attacks.

To address these issues, we conducted an online case-crossover study and examined the relation of a set of potential triggers, including total amount of purine intake as well as purine from animal and plant sources, to the risk of recurrent gout attacks. We also assessed whether the impact of purine intake varied by other known major risk factors of gout.

METHODS

The details of the Online Case-Crossover Study of Triggers for Recurrent Gout Attacks have been described previously.6 With this approach, each patient serves as his or her own control, and this self-matching eliminates confounding by risk factors that are constant within an individual during the study period but that differ between study subjects (eg, genetics, sex, race, education). Such a design has been successfully utilised in many previous studies where the impact of transient exposures on the risk of an acute event was evaluated (eg, triggering factors for myocardial infarction or motor vehicle collision).7,8

Study population

We constructed a study website on an independent secure server in the Boston University School of Medicine domain (https//dcc2.bumc.bu.edu/GOUT). The study was advertised on the Google search engine (www.Google.com) by linking an advertisement to the search term `gout.' Individuals who clicked on the study advertisement were directed to the study website and were asked the following: socio-demographic information, gout-related data (eg, diagnosis of initial gout attack, age of onset, medication used for treatment of gout and number of gout attacks in the last 12 months), and history of other diseases and medication use.

To be eligible for the study, a subject had to report gout diagnosed by a physician, have had a gout attack within the past 12 months, be at least 18 years of age, reside in the USA, provide informed consent, and agree to release medical records pertaining to gout diagnosis and treatment. To confirm a diagnosis of gout, we obtained medical records pertaining to the participant's gout history and/or a checklist of the features listed in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Preliminary Classification Criteria for Gout9 completed by the subject's physician. Two rheumatologists (DJH, TN) reviewed all medical records and the checklists and determined whether the participants had a diagnosis of gout according to the ACR criteria. Similar methods of gout diagnosis confirmation have been used in the Health Professional Follow-up Study.5 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus.

Ascertainment of recurrent gout attacks

Data were collected regarding the onset date of the recurrent gout attack, anatomical location of the attack, clinical symptoms and signs (maximal pain within 24 h or redness) and medications used to treat the attack (ie, colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), systemic corticosteroids, intra-articular corticosteroid injections). Our method of identifying gout attacks is in keeping with approaches used in acute and chronic gout trials10–13 and the ACR/EULAR supported initiative for defining gout attacks that includes only patient reported elements.14 We further evaluated the robustness of our results by restricting our analyses to those treated with at least one antigout medication (as listed above), those with podagra, those whose attacks resulted in maximal pain within 24 h and those who had redness over their joint(s) during the attack. We also evaluated combinations of these features (ie, those with ≥2, ≥3 and all 4 features).

Ascertainment of risk factors

Participants were queried about the presence of a set of potential risk factors (ie, dietary factors, medication use, infection, immunisations, physical activity and geographic location) during the 2-day period prior to the gout attack (ie, hazard period) as well as at the following time points that were control periods: at study entry (for the subjects who entered the study during an intercritical period), and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 (for the subjects who entered the study at the time of a gout attack) months of follow-up. The questions used to assess the risk factors during the control period were the same as those used in the hazard period.

Questions on food intake included the number and size of servings of each food consumed on each day of the prior 2 days for the control and the hazard periods. The food items included all high-purine content of foods (eg, all meats, organ meats, meat extracts and gravies, seafood, beans, peas, lentils, oatmeal, spinach, asparagus, mushroom, yeast, beer and other alcoholic beverages (including wine and liquor)).15 We estimated the total amount of purine intake from all foods consumed during these periods according to the published purine content of each food item.16,17

Statistical analysis

The total amount of purine intake over 2 days was divided into quintile groups. We examined the relation of total purine intake to the risk of recurrent gout attacks using a conditional logistic regression model, which accounts for the matching of each individual's own hazard and control periods. Each person can have more than one hazard and/or more than one control period. In a multivariable regression model, we adjusted for use of alcohol, allopurinol and diuretics. Using the same approach, we evaluated the effect of purine intake from animal sources (ie, meat, seafood) separately from plant sources (ie, vegetables, fruits) on the risk of recurrent gout attacks. Finally, we assessed potential subgroup effects of purine consumption according to sex, alcohol (ie, either beer, or wine, or liquor) use (yes vs no), allopurinol use (yes vs no), diuretic use (yes vs no), NSAIDs use (yes vs no) as well as colchicine use (yes vs no), and tested for a modification of effect by adding an interaction term to our final multivariable regression models.

RESULTS

We analysed 633 gout patients who completed both hazard period and control period questions. Of them, 554 (87.5%) participants met the ACR Preliminary Classification Criteria for Gout and 78 (12.3%) had crystal-proven gout based on medical records review. The characteristics of the participants are presented in table 1. The average age of the participants was 54 years. Participants were predominantly men (78%), Caucasian (88%), and over a half had received college education. Subjects were recruited from 49 states and the District of Columbia. About 61% of participants consumed alcohol, 29% used diuretics, and 45% took allopurinol, 54% used NSAIDs and 25% took colchicines during either hazard or control periods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 633 participants in the internet-based case-crossover study of gout

| Characteristics | N=633 |

|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Men | 494 (78.0%) |

| Age (median, range) | 54 (21–88) |

| Education (n, %) | |

| Less than high school graduate | 10 (1.6) |

| High school graduate | 55 (8.7) |

| Some college/technical school | 199 (31.4) |

| College graduate | 157 (24.8) |

| Some professional/graduate school | 70 (11.1) |

| Completed professional or graduate school | 142 (22.4) |

| Household income in US$ (n, %) | |

| <25,000 | 51 (8.1) |

| 25 000–49 999 | 127 (20.7) |

| 50 000–74 999 | 121 (19.1) |

| 75 000–99 999 | 89 (14.1) |

| >100 000 | 163 (25.8) |

| Refuse to answer | 82 (13.0) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| Black | 19 (3.0) |

| White | 558 (88.2) |

| Other | 48 (7.6) |

| Refuse to answer | 8 (1.3) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, median, range) | 30.6 (14.7, 69.9) |

| Years of disease duration (median, range) | 5 (0–49) |

| Alcohol drinkers* (n, %) | 383 (60.5) |

| Diuretic users* (n, %) | 184 (29.1) |

| Allopurinol users* (n, %) | 285 (45.0) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users* (n, %) | 342 (54.0) |

| Colchicine users* (n, %) | 160 (25.3) |

During either hazard or control periods.

During the 1-year follow-up period, we documented 1247 recurrent gout attacks. Most gout attacks occurred in the lower extremity (92%), particularly in the first metatarsophalangeal joint, and had features of either maximal pain within 24 h or redness (89%). Approximately 90% of the gout attacks were treated with colchicine, NSAIDs, systemic corticosteroids, intra-articular corticosteroid injections or a combination of these medications. The median time between the onset of a gout attack and completion of the hazard period questions was 3 days.

The median amount of purine intake over a 2-day control period was 1.66 g (the equivalent of ~ 1.4 kg of beef or 2.9 kg of spinach) in men and 1.38 g (the equivalent of ~ 1.2 kg of beef or 2.4 kg of spinach) in women, respectively. The corresponding figures over a 2-day hazard period were 2.03 g (the equivalent of ~ 1.7 kg of beef or 3.6 kg of spinach) and 1.66 g (the equivalent of ~ 1.4 kg of beef or 2.9 kg of spinach), respectively.

As shown in table 2, compared with the lowest quintile of purine intake over a 2-day period, the OR for recurrent gout attacks were 1.17, 1.38, 2.21 and 4.76, respectively, with each increasing quintile (p for trend < 0.001). When we limited the analysis to participants who met to the ACR Preliminary Classification Criteria for Gout (n=554), the corresponding multivariable OR were 1.13, 1.35, 2.15 and 4.61, respectively (p for trend < 0.001). In addition, when we varied our definition of recurrent gout attacks by requiring specific features individually or in combination, the results did not change materially. For example, when we limited the analysis to those who had at least two of the four features (n=606) (antigout medication use, podagra, maximal pain within 24 h and redness), the corresponding multivariable OR were 1.20, 1.44, 2.32 and 5.47 (p for trend < 0.001). Furthermore, when we excluded patients treated with febuxostat (N=7), our results did not change materially (OR=4.76 for highest quintile of purine intake; p for trend <0.001).

Table 2.

Total purine consumption and risk of recurrent gout attack

| Total purine intake over 2 days (g, median) | Number of control periods | Number of hazard periods | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 (0.85) | 363 | 203 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Quintile 2 (1.30) | 359 | 209 | 1.21 (0.92 to 1.59) | 1.17 (0.88 to 1.55) |

| Quintile 3 (1.74) | 348 | 219 | 1.43 (1.06 to 1.91) | 1.38 (1.02 to 1.87) |

| Quintile 4 (2.28) | 301 | 267 | 2.32 (1.72 to 3.13) | 2.21 (1.62 to 3.01) |

| Quintile 5 (3.48) | 218 | 349 | 4.98 (3.55 to 6.98) | 4.76 (3.37 to 6.74) |

| p For trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for use of alcohol, diuretics, allopurinol, colchicines and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

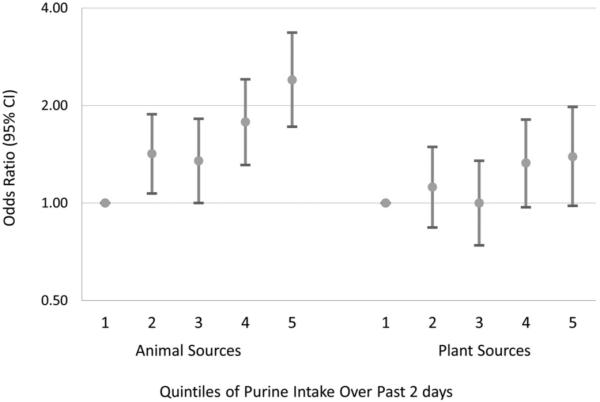

The effect of purine intake from animal sources and plant sources on the risk of recurrent gout attacks is shown in figure 1. The median amount of purine intake over a 2-day period from animal sources (0.87 grams) was five times higher than that from plant sources (0.16 g). Compared with the lowest quintile of purine intake from animal sources, OR of recurrent gout attacks were 1.42 (95% CI: 1.07 to 1.87), 1.34 (95% CI: 0.99 to 1.80), 1.77 (95% CI: 1.30 to 2.41) and 2.41 (95% CI: 1.72 to 3.36), respectively, with each increasing quintile (p for trend < 0.001). The corresponding OR for purine intake from plant sources were 1.12 (95% CI: 0.84 to 1.49), 0.99 (95% CI: 0.73 to 1.34), 1.32 (95% CI: 0.97 to 1.81) and 1.39 (95% CI: 0.98 to 1.98) (p for trend = 0.04), respectively.

Figure 1.

Estimated OR for recurrent gout attacks related to the source of purine intake.

The effect of purine intake on the risk of recurrent gout attacks persisted across subgroups by sex, age, use of alcohol, diuretics, allopurinol, NSAIDs and colchicine (all p values for trend <0.01) (table 3). The associations did not vary significantly by these factors (all p values for interaction > 0.1) except by diuretic use in which the relative effect of purine on the risk of recurrent gout attacks was greater when subjects did not use diuretics even though the diuretic use was associated with an increased risk of recurrent gout attacks in the current study.18

Table 3.

Total purine consumption and risk of recurrent gout attack in subgroups by sex, alcohol consumption, use of diuretics, allopurinol, colchicine and NSAIDs

| Other risk factors over 2 days | Quintile of purine intake over 2 days | Number of control periods | Number of hazard periods | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | p For trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Quintile 1 | 290 | 156 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 285 | 162 | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.52) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 275 | 171 | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.94) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 235 | 212 | 2.34 (1.64 to 3.33) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 175 | 271 | 4.83 (3.25 to 7.18) | ||

| Women | Quintile 1 | 73 | 47 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 74 | 47 | 1.45 (0.79 to 2.67) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 73 | 48 | 1.44 (0.77 to 2.71) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 66 | 55 | 1.86 (0.98 to 3.52) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 43 | 78 | 4.73 (2.28 to 9.84) | ||

| Age <55 | Quintile 1 | 169 | 94 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 166 | 101 | 1.31 (0.87 to 1.96) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 161 | 121 | 1.84 (1.19 to 2.84) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 145 | 143 | 2.50 (1.63 to 3.86) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 111 | 153 | 4.21 (2.56 to 6.92) | ||

| Age ≥55 | Quintile 1 | 194 | 109 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 193 | 108 | 1.08 (0.73 to 1.61) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 187 | 98 | 1.02 (0.67 to 1.57) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 156 | 124 | 1.91 (1.22 to 2.99) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 107 | 196 | 5.43 (3.20 to 8.91) | ||

| Alcohol intake | Quintile 1 | 138 | 65 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 143 | 92 | 1.17 (0.72 to 1.91) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 120 | 76 | 1.32 (0.72 to 1.91) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 121 | 112 | 2.07 (1.19 to 3.62) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 80 | 162 | 4.91 (2.66 to 9.08) | ||

| No alcohol intake | Quintile 1 | 225 | 138 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 216 | 117 | 1.17 (0.72 to 1.91) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 228 | 143 | 1.44 (0.97 to 2.13) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 180 | 155 | 2.32 (1.54 to 3.48) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 138 | 187 | 4.13 (2.59to 6.56) | ||

| Diuretic use | Quintile 1 | 67 | 63 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.006 |

| Quintile 2 | 65 | 52 | 0.82 (0.44 to 1.52) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 66 | 60 | 1.11 (0.57 to 2.15) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 55 | 62 | 1.36 (0.67 to 2.75) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 50 | 91 | 2.78 (1.28 to 6.04) | ||

| No diuretic use | Quintile 1 | 296 | 140 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 294 | 157 | 1.31 (0.94 to 1.81) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 282 | 159 | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.07) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 246 | 205 | 2.54 (1.78 to 3.64) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 168 | 258 | 5.52 (3.69 to 8.28) | ||

| Allopurinol use | Quintile 1 | 119 | 49 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 114 | 59 | 1.41 (0.80 to 2.50) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 119 | 51 | 1.44 (0.76 to 2.77) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 97 | 61 | 1.70 (0.88 to 3.29) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 65 | 85 | 5.51 (2.57 to 11.8) | ||

| No allopurinol use | Quintile 1 | 244 | 154 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 245 | 150 | 1.04 (0.73 to 1.48) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 229 | 168 | 1.27 (0.89 to 1.83) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 204 | 206 | 2.16(1.48 to 3.16) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 153 | 264 | 4.35 (2.85 to 6.64) | ||

| Colchicine use | Quintile 1 | 74 | 34 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 42 | 24 | 2.46 (0.92 to 6.59) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 43 | 18 | 1.19 (0.32 to 4.38) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 35 | 27 | 3.26 (1.00 to 10.6) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 29 | 41 | 13.2 (3.24 to 53.6) | ||

| No colchicine use | Quintile 1 | 289 | 169 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 317 | 185 | 1.08 (0.80 to 1.47) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 305 | 201 | 1.29 (0.93 to 1.79) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 266 | 240 | 1.95 (1.39 to 2.74) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 189 | 308 | 4.20 (2.88 to 6.13) | ||

| NSAIDs use | Quintile 1 | 85 | 44 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 91 | 56 | 1.66 (0.84 to 3.29) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 104 | 54 | 1.23 (0.59 to 2.58) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 79 | 73 | 2.72 (1.31 to 5.66) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 53 | 115 | 6.36 (2.76 to 14.7) | ||

| No NSAIDs use | Quintile 1 | 278 | 159 | 1.0 (referent) | <0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 268 | 153 | 1.20 (0.86 to 1.69) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 244 | 165 | 1.65 (1.15 to 2.39) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 222 | 194 | 2.37 (1.63 to 3.47) | ||

| Quintile 5 | 165 | 234 | 5.12 (3.32 to 7.90) |

Adjusted for use of alcohol, diuretics, allopurinol, colchicine and non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drug (NSAIDs).

DISCUSSION

Although purine-rich food intake has been anecdotally considered a risk factor for recurrent gout attacks, to our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to formally test this hypothesis and quantify the magnitude of the association. We found that the highest quintile of purine intake, mainly from animal sources, over a 2-day period increases the risk of recurrent gout attacks almost by five times compared with the lowest quintile of purine intake. These associations were independent of other risk factors for gout such as sex, alcohol consumption, and use of allopurinol or diuretics. The associations persisted across subgroups stratified by these major risk factors.

Recurrent attacks are a hallmark of untreated or inadequately treated gout. In our online gout study, we have found that approximately two-thirds of participants who had gout attacks in the previous year experienced at least one recurrent gout attack in the following year.3 While urate-lowering therapy (eg, allopurinol in >90% of cases in the USA and Europe) can be generally effective in lowering levels of serum urate and the risk of gout when used compliantly, urate-lowering therapy is currently primarily recommended for specific indications such as frequent gout attacks and tophaceous gout, primarily due to rare but serious side effects.19 Thus, when such indications are not yet met or urate-lowering therapy is not otherwise feasible, dietary manipulation and other risk factor modifications are appropriate options. Furthermore, these measures should continue as adjunct measures to aid pharmacological urate-lowering therapy. This approach is strongly supported by our finding that even among allopurinol users acute purine intake can increase the risk of recurrent gout attacks by more than five times.

Our findings and the long-standing anecdotal observation that intake of purine-rich foods can increase the risk of recurrent gout attacks are supported by metabolic experiments in animals and humans that examined the impact of artificial short-term loading of purified purine on serum urate levels (not gouty arthritis per se).20 More recently, studies have shown that higher levels of meat/seafood consumption are associated with higher levels of serum urate,4 and habitually higher meat and seafood intake is strongly associated with an increased risk of incident gout5 among individuals without gout at baseline. Our findings extend the evidence to a clinically relevant context, recurrent gout attacks among patients with existing gout, and indicate that avoiding or reducing purine-rich foods, especially of animal origin (that tend to have higher purine content than those of plant origin), would help reduce recurrent gout attacks.

We found that the short-term impact of purine from plant sources on the risk of gout attacks was substantially smaller than that from animal purine sources. Also, in a large prospective study of incident gout, the long-term, habitual consumption of purine-rich vegetables was not associated with the risk of incident gout.5 Interestingly, in that study, the highest quintile of vegetable protein consumption was actually associated with a 27% lower risk of gout compared with the lowest quintile.5 Our analysis of purine quantities suggests that these findings of small or null effects of purine intake from plant sources can be explained by the substantially lower amounts of purine content in those food items. Other healthy nutrients of vegetable items (eg, fibre or healthy fat) could contribute to reducing long-term weight gain21 and lowering insulin resistance. Of note, these plant-derived food items are key components of dietary approaches to reduce insulin resistance, which have been advocated as a long-term antigout dietary measure.22,23 These findings have important implications for patients with gout, since plant-derived food items are virtually the only protein sources to meet their nutrient needs once animal protein sources are eliminated from their diets. Furthermore, low-protein/purine dietary approach may lead to higher consumption of foods that are often rich in refined carbohydrates and saturated fat which may worsen both gout and its comorbidities by promoting insulin-resistance and increasing levels of serum urate, plasma glucose, triglycerides and LDL-C.22,23 To that effect, our findings support the notion that plant-derived foods should be the preferred sources of protein for gout patients, given that plant food items (especially, nuts and legumes) are excellent sources of protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals, and studies have found their benefits against the risk of weight gain,21 coronary heart disease,24,25 sudden cardiac deaths26 and type 2 diabetes.27

Several features of the current study are worth noting. Identifying potential triggers for recurrent gout attacks and assessing their effects are challenging when using conventional study designs. For example, a case-control study would pose difficulties for valid control selection, while a cohort design would be costly and unwieldy for participants. The case-crossover study uses each case as his/her own control and is highly adaptable to examining associations of triggers with acute events.28 In addition, to help overcome recruitment challenges of conventional study designs, we used the internet to recruit a large number of subjects with gout from the entire USA. These methods allowed us to assess both exposure and disease occurrence in real-time while minimising the potential of recall bias.

Our study has some limitations. First, while the current study design allows us to assess the acute effects of dietary purine intake on the risk of recurrent gout attacks, it is not ideal for examining the long-term effects of habitual purine consumption. Second, the amount of purine from various foods consumed over the 2-day period was based on dietary recall according to the serving size and number of servings of each food consumed; thus, recall bias is possible. Nonetheless, such data allow us to classify categories of purine intake over a specific time period relative to that over other time periods for the same person. Third, the purine content of each food item used in the current study was mainly based on raw foods, but the bioavailability of purine contained in different foods varies when they are cooked or processed.29 In the current study, we were unable to estimate purine intake that accounts for the food preparation process and this might have led to misclassification of purine exposure. Nevertheless, this type of misclassification would be non-differential and therefore would have biased the study results toward the null. Fourth, we did not collect data on serum urate levels for each study participant; thus, we were unable to assess whether purine-rich food intake over a short period would increase the risk of gout attacks even among subjects whose serum urate was below the threshold level. However, when we limited our analysis to subjects who reported taking allopurinol during the follow-up period (n=285), the risk of recurrent gout attacks was still increased when individuals increased their purine intake, even though allopurinol use itself was associated with lower risk of recurrent gout attacks. Finally, characteristics of study participants and distribution of purine intake may not be representative of US gout patients; however, the biological effects of purine intake on gout attacks should not differ.

In conclusion, our study findings suggest that acute purine intake increases the risk of recurrent gout attacks by almost five times among patients with gout. The impact from animal purine sources was substantially greater than that from plant purine sources. Avoiding or reducing purine-rich foods intake, especially of animal origin, may help reduce the risk of recurrent gout attacks.

Acknowledgments

Funding Arthritis Foundation, American College Rheumatology Research and Education Fund, and NIH.

Footnotes

Contributors YZ and TN had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests None.

Ethics approval Approval provided by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41. doi: 10.1002/art.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutman AB. The past four decades of progress in the knowledge of gout, with an assessment of the present status. Arthritis Rheum. 1973;16:431–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780160402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neogi T, Hunter DJ, Chaisson CE, et al. Frequency and predictors of inappropriate management of recurrent gout attacks in a longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:104–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:283–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1093–103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Chaisson CE, McAlindon T, et al. The online case-crossover study is a novel approach to study triggers for recurrent disease flares. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, et al. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. Protection against triggering by regular exertion. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1677–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostofsky E, Burger MR, Schlaug G, et al. Alcohol and acute ischemic stroke onset: the stroke onset study. Stroke. 2010;41:1845–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060–8. doi: 10.1002/art.27327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundy JS, Baraf HS, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.So A, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A, et al. Canakinumab for the treatment of acute flares in difficult-to-treat gouty arthritis: Results of a multicenter, phase II, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3064–76. doi: 10.1002/art.27600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaffo AL, Schumacher HR, Saag KG, et al. Developing a provisional definition of a flare in patients with established gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1508–17. doi: 10.1002/art.33483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emmerson BT. The management of gout. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:445–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfram G, Colling M. Total purine content in selected foods. Z Ernahrungswiss. 1987;26:205–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02023808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata E, Fujimori S, Kaneko K. Contents of purine bases in foods and alcoholic beverages. Nippon Rinsho. 2003;61(Suppl 1):489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter DJ, York M, Chaisson CE, et al. Recent diuretic use and the risk of recurrent gout attacks: the online case-crossover gout study. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1341–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clifford AJ, Riumallo JA, Young VR, et al. Effect of oral purines on serum and urinary uric acid of normal, hyperurecemic and goulty humans. J Nutr. 1976;106:428–34. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, et al. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2392–404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fam AG. Gout, diet, and the insulin resistance syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1350–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dessein PH, Shipton EA, Stanwix AE, et al. Beneficial effects of weight loss associated with moderate calorie/carbohydrate restriction, and increased proportional intake of protein and unsaturated fat on serum urate and lipoprotein levels in gout: a pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:539–43. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.7.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317:1341–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7169.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ. Nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a review of epidemiologic evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 1999;1:204–9. doi: 10.1007/s11883-999-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Willett WC, et al. Nut consumption and decreased risk of sudden cardiac death in the Physicians' Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1382–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.12.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Nut and peanut butter consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA. 2002;288:2554–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maclure M, Mittleman MA. Should we use a case-crossover design? Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson T, Rodgers AV, Simmonds HA, et al. A controlled study of diet in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42:123–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.42.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]