Abstract

Brucellosis is a serious zoonosis that occurs worldwide, and its diagnosis is typically based on the detection of antibodies against Brucella lipopolysaccharide (LPS). However, the specificity of the LPS-based test is compromised by cross-reactivity with Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Yersinia enterocolitica O:9. Also, diagnosis based on the LPS test cannot differentiate between vaccinated and infected individuals. The detection of the 26-kDa cytosoluble protein (BP26) antibody is considered an alternative that circumvents these drawbacks because it is exclusively expressed by infectious Brucella. A BP26-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has been tried for the diagnosis of Brucella-infected animals and humans, but a few results showed that BP26 couldn't react with all Brucella-positive sera. In order to explore whether different animals could produce antibodies against BP26 after being infected with various Brucella species, we infected sheep, goats, and beef cattle with common virulent reference Brucella species. All sera were collected from the experimental animals and tested using both LPS-based ELISAs and BP26-based ELISAs. The results showed that all Brucella-infected individuals could produce high levels of antibodies against LPS, but only B. melitensis 16M- and B. melitensis M28-infected sheep and B. melitensis 16M- and B. abortus 2308-infected goats could produce antibodies against BP26. Therefore, we concluded that the BP26-based indirect ELISA (i-ELISA) showed both Brucella species and host specificity, which obviously limits its reliability as a substitute for the traditional LPS-based ELISA for the detection of brucellosis.

INTRODUCTION

Brucella is a Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterial pathogen that causes one of the world's most widely spread zoonotic infections, including infectious abortion in animals and Malta fever in humans (1, 2). Brucella species include Brucella melitensis (natural host: goat), Brucella abortus (cattle), Brucella ovis (sheep), Brucella suis (swine), Brucella canis (dogs), and Brucella neotomae (desert rats) as well as some strains that infect marine mammals (3). Besides their natural hosts, most Brucella species also infect other animals. B. melitensis and B. abortus are considered to be major health threats because of their highly infectious nature and worldwide occurrence (3–5). Control of brucellosis depends on reliable diagnostic methods.

The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of smooth Brucella species is an antigen of strong reactivity and can elicit a long-lasting serological response in both vaccinated and infected animals (6, 7). Serological tests based on the detection of antibodies against lipopolysaccharide (LPS), like the Rose Bengal plate agglutination test, the complement fixation test, the fluorescence polarization assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) display satisfying specificity and sensitivity and therefore are widely used for the diagnosis of brucellosis. Among these serological tests, ELISAs showed the highest sensitivity and specificity (8, 9). However, it is difficult to differentiate vaccinated animals from infected ones using LPS-based serological tests (10). In addition, cross-reaction can occur between Escherichia coli O157:H7, Yersinia enterocolitica O:9, and B. abortus, so the LPS-based serological tests may yield false-positive results (11).

Therefore, researchers are focusing on identifying diagnostic methods of higher specificity, such as non-LPS antigen-based tests, in which the drawbacks of the LPS-based test can be circumvented. In 1996, Cloeckaert et al. found that the 28-kDa cytosoluble protein (BP26) of Brucella melitensis showed high immunogenicity in infected sheep and could be used to differentiate the B. melitensis Rev. 1-vaccinated sheep from those infected with B. melitensis H38 (12). Subsequently, scientists established and evaluated indirect-ELISA (i-ELISA) and competitive-ELISA (c-ELISA), which were based on the detection of antibodies against BP26 (13, 14). According to previous data, the sensitivity of BP26-based ELISAs ranges from 88.7% to 100%, and the specificity ranges from 85.59% to 98.41% (15–17). Most published studies indicate that BP26-based ELISA can be used for the diagnosis of B. melitensis- or B. ovis-infected sheep or goats (12, 13, 15, 18, 19); however, data obtained from using other Brucella species or other animal species are rare (8, 14). Furthermore, some published data showed that the recombinant BP26 protein was not recognized by sera obtained from B. abortus 2308-infected cattle, swine naturally infected with B. suis (14), or patients with chronic brucellosis using Western blotting (20). In order to examine the bacterial species and host species for which the BP26 test is applicable, we evaluated Brucella infections with different species and in different hosts, using the LPS test as the control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

All animals used in this research were treated with care, and this study was approved by the China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control.

Bacterial species and plasmids.

Brucella species were obtained from the China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control, Beijing, China. B. melitensis 16M (biotype 1, virulent), B. melitensis M28 (biotype 1, isolated in China and used as a Brucella reference species in China) (21, 22), B. abortus 2308 (biotype 1, virulent), and B. suis S1330 (biotype 1, virulent) were used in the present study. All Brucella strains were checked for purity, species, and biovar characterization by standard procedures. Plasmid pET32a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI) was used as the expression vector, and E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was used for protein expression in this study.

Expression and purification of recombinant BP26a.

The amino acid sequences of BP26 are identical among B. melitensis 16M (GenBank accession no. AE008918), B. melitensis M28 (GenBank accession no. CP002459.1), B. abortus 2308 (GenBank accession no. AM040264.1), and B. suis S1330 (GenBank accession no. AE014291.4). Genomic DNA was isolated from B. abortus 2308 using the Genomic DNA minipreparation kit with spin column (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −80°C. The bp26 gene was amplified by PCR using sense primer 5′-CGCGGATCCATGAACACTCGTGCTAGCAAT-3′ and antisense primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTTTACTTGATTTCAAAAACGAC-3′, designed according to the gene sequence of B. melitensis 16M (GenBank accession no. AE008918). The PCR mixture containing 0.4 μM each primer, 2 μl DNA, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture, 25 μl 2× GC buffer (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and 1.25 U Pfu DNA polymerase (Fermentas) was brought to a final volume of 50 μl with double-distilled water. The PCR was initiated with a 10-min 95°C denaturation, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 45 s), annealing (54°C, 45 s), extension (72°C, 45 s), and a final extension (72°C, 10 min). The PCR product was digested by HindIII and BamHI (TaKaRa) after purification using E.Z.N.A. gel extraction kit (Omega, USA) and the digested product was cloned into expression vector pET32a(+) with the same restriction sites. The generated recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α. The recombinants were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing (Songong Biotech, Shanghai, China).

The constructed plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Transformants were plated on LB solid medium containing ampicillin (50 ng/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 12 to ∼16 h. A single clone was selected and grown in LB medium with ampicillin until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6 to 0.8. The cells were then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and cultured at 22°C for 12 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS [pH 7.4]). Cells were resuspended in 10 ml of PBS (pH 7.4) and lysed by sonication after washing. Following sonication, lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the recombinant protein BP26 was recovered from the supernatant of sonicated recombinant E. coli cells in a soluble form. The BP26 was purified by HisTrap affinity column (HisTrap FF Crude, 1 ml; GE Healthcare, Germany) using AKTA purifier and exchanged into PBS (pH 7.4) with a HiTrap 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Germany). The purified BP26 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay.

In order to identify the recombinant BP26, the purified protein was digested by thrombin (Sigma, USA) at 22°C for 1 h and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. The target fragment (nearly 26 kDa) was carved and analyzed by the tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) method using Applied Biosystems 4700 proteomics analyzer 7044 (Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, SIBS, CAS, Shanghai, China).

LPS-based i-ELISA and c-ELISA.

Two commercial LPS-based ELISA kits (i-ELISA kit and c-ELISA kit) were used in parallel to detect all serum samples collected from the experimental cattle, sheep, and goats to detect IgG antibodies against Brucella LPS. All serum samples were tested using the LPS-based i-ELISA kit (Pourquier ELISA brucellosis individual and pool serum screening; P04130/10) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After the optical density was read at 450 nm (OD450) for all of the plates, the sample/positive (S/P) ratio of each serum sample was calculated as follows: S/P (%) = 100 × [(OD450 sample − OD450 negative control)/(mean OD450 positive control − OD450 negative control)].

The manufacturers' recommended cutoff value for cattle was 110%. Those with an S/P ratio higher than 120% were considered to be from cattle that had specific antibodies to Brucella LPS. Any samples with an S/P ratio between 110% and 120% were considered indeterminate. However, because there has been no cutoff for sheep or goats so far, the cutoff value for sheep was calculated by analyzing the S/P ratios of 10 negative sera from healthy sheep (from a Brucella-free herd and shown to be negative by the Rose Bengal plate agglutination test and the complement fixation test) and 20 positive sera from Brucella experimentally infected sheep by receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis (GraphPad Prism 5 software). The cutoff value for goats was calculated by analyzing the S/P ratios of 10 negative sera from healthy goats (from a Brucella-free herd and shown to be negative by the Rose Bengal plate agglutination test and the complement fixation test) and 20 positive sera from Brucella experimentally infected goats on the same program.

All serum samples from experimental cattle, sheep, and goats were also tested using the LPS-based c-ELISA kit (Svanovir Brucella-Ab C-ELISA test kit; 10-2701-10) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After the OD450 values of the plates were read, the percent inhibition (PI) values were calculated using the following formula: PI = 100% − [100% × (ODsample/mean ODconjugate control)]. The manufacturers' recommended cutoff value for cattle was 30%. Samples with a PI of ≥30% were considered to be from animals having specific antibodies to Brucella LPS. However, because there is no cutoff for sheep or goats so far either, the cutoff value for sheep was calculated by analyzing the PI of 10 negative sera from healthy sheep (from a Brucella-free herd and shown to be negative by the Rose Bengal plate agglutination test and the complement fixation test) and 20 positive sera from Brucella experimentally infected sheep on ROC analysis. The cutoff value for goats was calculated by analyzing PI of 10 negative sera from healthy goats (from a Brucella-free herd and which showed negative by the Rose Bengal plate agglutination test and the complement fixation test) and 20 positive sera from Brucella experimentally infected goats on the same program.

Recombinant BP26-based i-ELISA.

The antigen concentration, dilution ratio of serum samples, reaction time, and blocking solution were optimized for BP26-based i-ELISA. The established BP26-based i-ELISA was performed as follows. The 96-well polystyrene microplates were coated overnight at 4°C with purified BP26 at 1 μg/ml in 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6; 100 μl/well). Before use, the antigen-coated plates were washed 6 times with Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T [pH 7.4]) and then blocked with 5% chicken serum (2 h at 37°C). Serum samples were diluted 1:100 in TBS-T and added in duplicate to the coated wells. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed 6 times with TBS-T. For detection of goat or sheep serum samples, the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with mouse monoclonal anti-goat/sheep IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Sigma) diluted 1: 30,000 in TBS-T. The plates were washed 6 times with TBS-T, and 100 μl of substrate solution containing 3, 3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added to each well. They were then incubated for 15 min in dark at room temperature, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl 2 M H2SO4 to each well. The OD450 values were measured using an automatic microplate reader. For detection of cattle serum samples, the plates were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-bovine IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma) diluted 1:15,000 in TBS-T for 1 h at 37°C. After the plates were washed 6 times with TBS-T, 100 μl of substrate solution (10 ml substrate solution containing 2 tablets of p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 1 ml diethanolamine, and 0.5 mM MgCl2, with pH adjusted to 9.8 with HCl) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl 0.4 M NaOH per well. The OD405 values were measured using an automatic microplate reader. Two serum samples from B. melitensis-infected sheep and two sera from healthy sheep were diluted in 1:20, 1:40, 1:80, 1:160, and 1:320 with TBS-T and detected by this kit to confirm the reliability of the BP26-based i-ELISA kit.

Animals and infection.

Fifteen female small-tail Han sheep, 15 female Boer goats, and 6 female Luxi beef cattle (widely raised in China), all aged 1 to 2 years, were randomly selected from brucellosis-free farms and raised in isolated pens under strict pathogen-free conditions. Animals were experimentally infected with different Brucella species (as listed in Table 1) through the conjunctival route. All animals were clinically monitored for 42 weeks postinfection, and serum samples were collected every 2 to 4 weeks. IgG antibodies against LPS or BP26 were detected by ELISAs.

Table 1.

Animals infected with different Brucella species

| Animal | Level of infection (no. of CFU/animal) with: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B. melitensis |

B. abortus 2308 | B. suis S1330 | PBS control | ||

| 16M | M28 | ||||

| Sheep | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 3 ml/animal |

| Goats | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 1 × 1011 | 3 ml/animal |

| Beef cattle | 1 × 1011 | 3 ml/animal | |||

Field trial.

In order to access the accuracy of BP26-based i-ELISA, 62 dairy cattle sera, 55 sheep sera, 58 goat sera, 62 dairy cattle sera, and 35 beef cattle sera were collected and detected in parallel by LPS-based ELISA kits and the BP26-based i-ELISA kit.

Bacteriology analysis.

All experimental infected animals and 10 naturally infected animals (including 2 dairy cattle, 3 sheep, 3 goats, and 2 beef cattle) were slaughtered after the experiment, and tissue samples were taken for Brucella culture according to the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) standard. The isolates were identified by AMOS-PCR as previously established in our lab.

The primers used are listed in Table 2. PCR mixture containing 0.1 μM FAbortus, Fsuis, RIS711, Feri, and Reri, 0.2 μM Fmelitensis, 1 μl DNA, 4 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture, 5 μl 10× buffer (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) was brought to a final volume of 50 μl with double-distilled water. The PCRs were initiated with a 10-min 95°C denaturation, followed by 29 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 1 min), annealing (60°C, 1.5 min), extension (72°C, 1.5 min), and a final extension (72°C, 10 min). The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels. IS711 products (Omega, USA) were digested with SphI (TaKaRa) and then analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels after purification using the E.Z.N.A. gel extraction kit to confirm the specificity of the PCR.

Table 2.

Primers used in AMOS-PCR

| Primer | Sequence | Size of fragment generated (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Fabortus | 5′-GACGAACGGAATTTTTCCAATCCC-3′ | 494 |

| Fmelitensis | 5′-AAATCGCGTCCTTGCTGGTCTGA-3′ | 733 |

| Fsuis | 5′-GCGCGGTTTTCTGAAGGTTCAGG-3′ | 285 |

| RIS711 | 5′-TGCCGATCACTTAAGGGCCTTCAT-3′ | |

| Feri | 5′-GCGCCGCGAAGAACTTATCAA-3′ | 178 |

| Reri | 5′-CGCCATGTTAGCGGCGGTGA-3′ |

All isolates were also identified by a sulfureted hydrogen test and serological identification according to the OIE standard.

Data analysis.

For the BP26-based i-ELISA, the serum antibody levels were evaluated using a cutoff value based on the average OD value for 20 Brucella-free serum controls plus 3 times the standard deviation. Agreement between tests was evaluated using the kappa (κ) coefficient.

RESULTS

Identification of recombinant BP26.

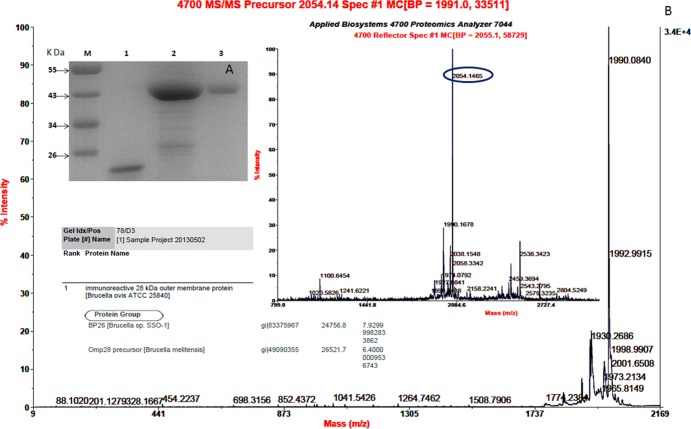

A fusion protein strategy was adopted to increase the expression of the BP26 protein, and recombinant BP26 was expressed with thioredoxin, S tag (S15), and His tag (the total molecular mass of the tags was 18 kDa) at the carboxyl terminus. The restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing analysis showed the bp26 gene was inserted into pET32a(+) vector successfully (data not shown). The proteins were separated in a 12% polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1 A), and the molecular mass of each protein matched the predicted molecular mass (44.5 kDa). The tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis confirmed the purified recombinant protein was BP26 (as shown in Fig. 1B). Purified BP26 with a purity of >90% at final concentrations of 0.6 mg/ml was used for the subsequent experiments.

Fig 1.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant BP26. Lanes: M, prestained protein ladder (Fermentas); 1, purified pET32a(+) tag; 2, BP26 expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3); 3, purified recombinant BP26. (B) Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis of the purified recombinant protein.

Brucella infection confirmed by LPS-based ELISAs.

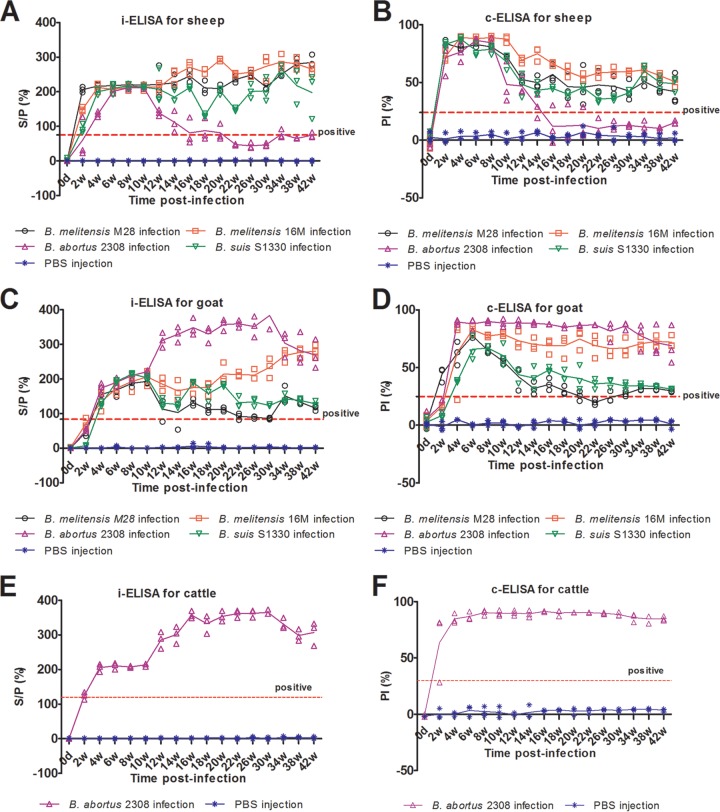

To confirm the efficacy of the LPS test for detection of Brucella infection, IgG antibodies against Brucella LPS were detected in the serum samples of the experimentally infected animals by using both i-ELISA and c-ELISA kits. As shown in Fig. 2, most sera from B. melitensis 16M-, B. melitensis M28-, and B. suis S1330-infected sheep, B. melitensis 16M- and B. abortus 2308-infected goats, and B. abortus 2308-infected beef cattle showed strong IgG antibody responses to Brucella LPS, and the antibodies against LPS persisted for more than 42 weeks. The LPS-based ELISA is effective for diagnosis of Brucella infection caused by various Brucella species and in different host species. However, the level of IgG antibodies in the sera from B. abortus 2308-infected sheep and B. melitensis M28- and B. suis S1330-infected goats gradually decreased over time. Especially the IgG antibodies against LPS in sera from B. abortus 2308-infected sheep could only last 12 to 16 weeks and then became nearly undetectable, while the antibodies against LPS in B. abortus 2308-infected goats and beef cattle could last more than 42 weeks. This may be related to the fact that the virulence of B. abortus 2308 to sheep was relative lower than that to goats and cattle, so the sheep may clear organisms from the system much faster than goats and cattle.

Fig 2.

IgG antibodies against LPS in serum samples from experimentally infected animals. Each point represents one serum sample tested in duplicate using ELISA, and the solid line denotes the reactivity for each animal. (A) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental sheep were tested using the i-ELISA kit. The cutoff was set as 75% by ROC analysis. (B) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental sheep were tested using the c-ELISA kit. The cutoff was set as 24% by ROC analysis. (C) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental goats were tested using the i-ELISA kit. The cutoff was set as 84% by ROC analysis. (D) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental goats were tested using the c-ELISA kit. The cutoff was set as 25% by ROC analysis. (E) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental cattle were tested using the i-ELISA kit. The cutoff was 110% of that recommended by the manufacturers. (F) The levels of antibodies against LPS in experimental cattle were tested using the c-ELISA kit. The cutoff was 30% of that recommended by the manufacturers.

Design of the BP26-based ELISA kit.

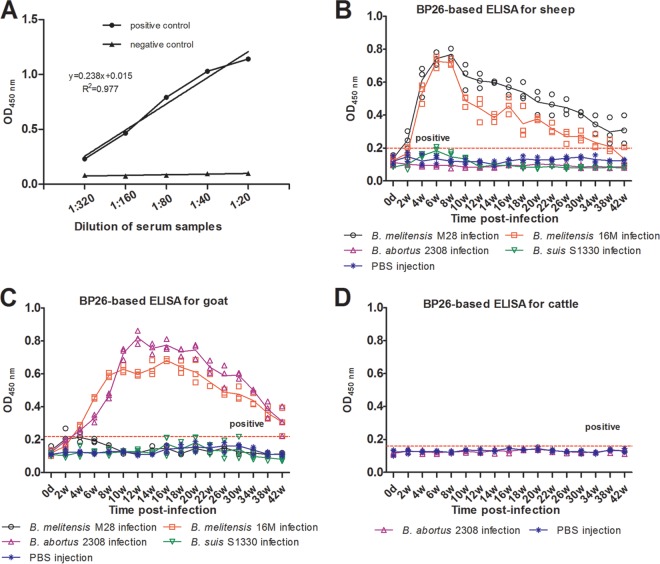

In evaluation of the quality of the BP26-based i-ELISA kit, positive and negative serum samples were diluted to different concentrations and tested by the kit. As shown in Fig. 3A, the kit we developed could identify different concentrations of BP26 antibodies in serum samples.

Fig 3.

IgG antibodies against BP26 in serum samples from experimental animals. Each point represents one serum sample tested in duplicate using ELISA, and the solid line denotes the reactivity for each animal. (A) Efficacy of the BP26-based i-ELISA. The positive control was the serum samples from B. melitensis-infected sheep, and the negative control was sera from healthy sheep. (B) The levels of antibodies against BP26 in experimental sheep were tested using the i-ELISA kit. (C) The levels of antibodies against BP26 in experimental goats were tested using the i-ELISA kit. (D) The levels of antibodies against BP26 in experimental cattle were tested using the i-ELISA kit.

BP26-based i-ELISA fails to detect all cases of Brucella infection.

To determine whether BP26-based i-ELISA could be used to detect infection caused by various Brucella species, the levels of IgG antibodies against recombinant BP26 in the sera of experimentally infected animals were measured by i-ELISA throughout the monitoring time. Antibody responses to BP26 in the experimental animals were analyzed using cutoff values of 0.20, 0.22, and 0.16 obtained from 20 healthy sheep, goats, and beef cattle, respectively, as mentioned before. As shown in Fig. 3B, C, and D, not all Brucella-infected animals showed positive results in the BP26-based i-ELISA (Table 3). We infected sheep and goats with four frequently used virulent reference Brucella species (including B. melitensis 16M, B. melitensis M28, B. suis S1330, and B. abortus 2308), respectively, but only B. melitensis M28- or B. melitensis 16M-infected sheep and B. melitensis 16M- and B. abortus 2308-infected goats could produce antibodies to BP26, and these antibodies could persist for more than 42 weeks (as shown in Fig. 3B and C), While sera from the B. suis S1330-infected sheep and goats and B. abortus 2308-infected sheep and beef cattle couldn't react with BP26 throughout the monitoring period.

Table 3.

Data from the present study regarding BP26-based ELISAs

| Animal | Result fora: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B. melitensis |

B. suis S1330 | B. abortus 2308 | ||

| 16M | M28 | |||

| Sheep | + | + | − | − |

| Goats | + | − | + | + |

| Beef cattle | ? | ? | ? | − |

+, can be tested using BP26-based ELISAs; −, cannot be tested using BP26-based ELISAs; ?, unknown.

In order to identify whether the BP26-based i-ELISA could detect all Brucella infections in naturally infected animals, 55 sheep sera, 58 goat sera, 62 dairy cattle sera, and 35 beef cattle sera were collected and detected in parallel by LPS-based i-ELISA or c-ELISA kits and the BP26-based i-ELISA kit. The results showed the BP26 based i-ELISA kit could be used to detect most Brucella-infected sheep and goats and showed good agreement with the LPS-based ELISA kit (κ > 0.5) (Table 4). The relative sensitivity and specificity of this kit to LPS-based ELISA kits in the detection of sheep and goats were more than 80% and 90%, respectively. However, the relative sensitivity of the BP26-based i-ELISA kit to LPS-based i/c-ELISA kits was only 50% for the detection in dairy cattle, and Brucella infection in beef cattle couldn't even be detected by this kit. Therefore, the BP26-based i-ELISA kit is unable to detect infection in all Brucella-infected animals.

Table 4.

Numbers of tested animals and agreement between the BP26-based i-ELISA and LPS-based i/c-ELISAs

| BP26-based i-ELISA result | No. of animals with result by LPS-based i/c-ELISAa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep |

Goats |

Cattle |

||||||

| Dairy |

Beef |

|||||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| Positive | 37 | 1 | 40 | 0 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative | 8 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 32 | 6 | 29 |

For the detection of infection in sheep, the relative specificity and sensitivity of BP26-based i-ELISA to LPS-based i/c-ELISAs were 90% and 82.2%, respectively; κ (agreement) = 0.5677 for the BP26-based i-ELISA and LPS-based i/c-ELISAs. For the detection in goats, the relative specificity and sensitivity of BP26-based i-ELISA to LPS-based i/c-ELISAs were 100% and 80%, respectively; κ = 0.5246 for the BP26-based i-ELISA and LPS-based i/c-ELISAs. For the detection in dairy cattle, the relative specificity and sensitivity of BP26-based i-ELISA to LPS-based i/c-ELISAs were 88.9% and 50%, respectively; κ = 0.4085 for the BP26-based i-ELISA and LPS-based i/c-ELISAs. For the detection in beef cattle, the relative specificity and sensitivity of BP26-based i-ELISA to LPS-based i/c-ELISAs were 100% and 0%, respectively; κ = 0 for the BP26-based i-ELISA and LPS-based i/c-ELISAs.

Bacteriology analysis.

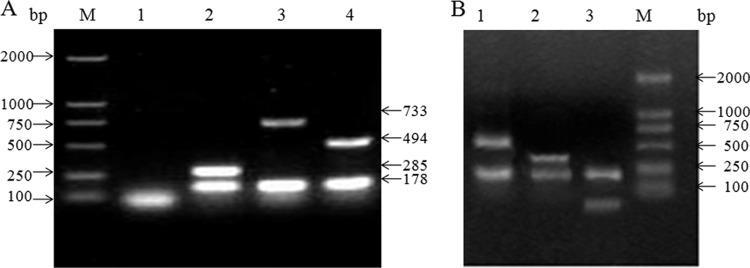

In the evaluation of BP26-based i-ELISA with truly infected animals, animals were slaughtered after the experiment. The infection of these animals was confirmed by Brucella culture (data not shown). All isolates were identified by the sulfureted hydrogen test, serological identification (data not shown), and AMOS-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, fragments of the expected size were successfully amplified from various isolates, respectively, and all of the IS711 PCR products could be digested by SphI successfully into target 215-bp fragments. However, the test is unable to differentiate the B. melitensis M28 strain from the B. melitensis 16M strain based on these tests.

Fig 4.

(A) AMOS-PCR analysis of Brucella isolates from experimentally infected animals. Lanes: M, DNA marker (DL2000); 1, negative control; 2, B. suis 1330 strain; 3, B. melitensis M28; 4, B. abortus 2308. (B) Digestion analysis of IS711 PCR products. Lanes: M, DNA marker (DL2000); 1, B. melitensis M28 (518 bp and 215 bp); 2, B. abortus 2308 (285 bp and 215 bp); and 3, B. suis 1330 strain (70 bp and 215 bp).

Ten naturally infected animals (including 2 dairy cattle, 3 sheep, 3 goats, and 2 beef cattle) were slaughtered after the experiment. However, only two Brucella strains were isolated successfully (one from a sheep, the other from a goat), and both of them were identified as B. melitensis (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The LPS-based i-ELISA and c-ELISA show high specificity and sensitivity and are considered to be the most effective methods for the diagnosis of brucellosis (8, 23). In our study, the Brucella-infected animals could be tested positive for brucellosis during 2 to 4 weeks postinfection; the anti-LPS antibodies persisted for nearly 42 weeks postinfection in the infected animals. However, the anti-LPS antibodies were nearly undetectable in the B. abortus 2308-infected sheep and B. melitensis M28- and B. suis S1330-infected goats 16 weeks postinfection, indicating that some clinical cases could have been neglected in epidemiological surveys of sheep or goat brucellosis, and the prevalence of Brucella could have been underestimated. This result is consistent with previous reports: Celik reported two brucellosis cases that were diagnosed as positive through bacterial culture or needle biopsy but tested negative in serological tests (24).

BP26, also termed CP28, belongs to group III antigens. In this study, we found that BP26-based i-ELISA showed bacterial species specificity (Table 3 and Fig. 3), that only sera from B. melitensis 16M-infected sheep and goats could react with BP26, and that sera from B. suis S1330-infected sheep and goats couldn't react with BP26. BP26-based i-ELISA also showed specificity to animal species: the BP26 humoral responses in sheep, goats, and beef cattle infected with B. abortus 2308 were different, and only sera from infected goats reacted with BP26. Furthermore, the sera from B. melitensis M28-infected sheep could react with BP26, but sera from goats infected by the same Brucella strain couldn't react with BP26. The detection of sera from naturally infected animals also confirmed that the BP26-based i-ELISA kit couldn't identify all Brucella-infected animals. Our results seem to be consistent with some published data that the recombinant BP26 protein may not recognized by sera obtained from B. abortus 2308-infected cattle, swine naturally infected with B. suis, or patients with chronic brucellosis (14, 20), but some other data showed that the BP26-based ELISA had high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of brucellosis in sheep, goats, cattle, and humans (13, 15–17). Chaudhuri et al. found that the Omp28-based ELISA showed 88.7% sensitivity and 93.8% specificity when used in the detection of bovine brucellosis (16). In 2011, Tiwari et al. (28) found that the recombinant 10-kDa immunodominant region of the BP26 protein of B. abortus could be used in the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. The different levels of antibodies against BP26 in different hosts after challenge with various Brucella strains might be related to the location and the different quantities of BP26 protein in exposure to host. However, the research about the location of BP26 has not been consistent so far. Lindler et al. found the BP26 located in the outer membrane and bleb (14); Rossetti et al. localized this protein in the periplasm (20); unlikely, Cloeckaert et al. found this protein localized exclusively intracellularly as a soluble protein by using certain monoclonal antibodies (12). Live Brucella dynamically adjusts its protein expression profile for survival in the host, and it may change enormously during the course of infection (25). Some proteins may be not expressed under laboratory conditions. Furthermore, even under the same experimental conditions, the protein expression profile of B. melitensis is different from that of B. abortus (26), so we speculate that BP26 may exist in various states in different host species infected with different Brucella strains (25, 27). Besides, immune responses may be directed to surface and/or internal proteins, depending on the processing of macrophages to the bacteria and the pathogenicity of the bacterial. Consequently, BP26-based i-ELISA is not reliable for the diagnosis of brucellosis. In future studies, we will examine the efficacy of combined antigens, which could compensate for the disadvantages of BP26-based ELISA and make it a suitable substitute for the LPS-based serological tests.

Conclusion.

Here, we focused on the application of the BP26 test in Brucella infections caused by various Brucella species in different hosts. The BP26-based ELISA showed bacterial and animal species specificity, and it was found to be unsuitable for the diagnosis of brucellosis. Nonetheless, we enriched the Brucella diagnosis spectrum and identified limitations in the BP26 test, especially in the detection of beef cattle, the most common meat source in China.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Special Fund for National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (no. 2012AA101302) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant 6101002).

We are especially grateful to the personnel at the farms involved in this study for collecting samples.

The authors of this article declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 July 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.de Jongand MF, Tsolis RM. 2012. Brucellosis and type IV secretion. Future Microbiol. 7:47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christopher S, Umapathy BL, Ravikumar KL. 2010. Brucellosis: review on the recent trends in pathogenicity and laboratory diagnosis. J. Lab Physicians 2:55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbel MJ. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manturand BG, Amarnath SK. 2008. Brucellosis in India—a review. J. Biosci. 33:539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chelli Bouaziz M, Ladeb MF, Chakroun M, Chaabane S. 2008. Spinal brucellosis: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 37:785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldi PC, Giambartolomei GH, Goldbaum FA, Abdon LF, Velikovsky CA, Kittelberger R, Fossati CA. 1996. Humoral immune response against lipopolysaccharide and cytoplasmic proteins of Brucella abortus in cattle vaccinated with B. abortus S19 or experimentally infected with Yersinia enterocolitica serotype 0:9. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3:472–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jimenez de Bagues MP, Marin CM, Blasco JM, Moriyon I, Gamazo C. 1992. An ELISA with Brucella lipopolysaccharide antigen for the diagnosis of B. melitensis infection in sheep and for the evaluation of serological responses following subcutaneous or conjunctival B. melitensis strain Rev 1 vaccination. Vet. Microbiol. 30:233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrett LL, McGiven JA, Brew SD, Stack JA. 2010. Evaluation of competitive ELISA for detection of antibodies to Brucella infection in domestic animals. Croat. Med. J. 51:314–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Praud A, Champion JL, Corde Y, Drapeau A, Meyer L, Garin-Bastuji B. 2012. Assessment of the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of an indirect ELISA kit for the diagnosis of Brucella ovis infection in rams. BMC Vet. Res. 8:68. 10.1186/1746-6148-8-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrio MB, Grillo MJ, Munoz PM, Jacques I, Gonzalez D, de Miguel MJ, Marin CM, Barberan M, Letesson JJ, Gorvel JP, Moriyon I, Blasco JM, Zygmunt MS. 2009. Rough mutants defective in core and O-polysaccharide synthesis and export induce antibodies reacting in an indirect ELISA with smooth lipopolysaccharide and are less effective than Rev 1 vaccine against Brucella melitensis infection of sheep. Vaccine 27:1741–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen K, Smith P, Widdison J, Gall D, Kelly L, Kelly W, Nicoletti P. 2004. Serological relationship between cattle exposed to Brucella abortus, Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 and Escherichia coli O157:H7. Vet. Microbiol. 100:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloeckaert A, Debbarh HS, Vizcaino N, Saman E, Dubray G, Zygmunt MS. 1996. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Brucella melitensis bp26 gene coding for a protein immunogenic in infected sheep. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 140:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debbarh HS, Zygmunt MS, Dubray G, Cloeckaert A. 1996. Competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using monoclonal antibodies to the Brucella melitensis BP26 protein to evaluate antibody responses in infected and B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccinated sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 53:325–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindler LE, Hadfield TL, Tall BD, Snellings NJ, Rubin FA, Van De Verg LL, Hoover D, Warren RL. 1996. Cloning of a Brucella melitensis group 3 antigen gene encoding Omp28, a protein recognized by the humoral immune response during human brucellosis. Infect. Immun. 64:2490–2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zygmunt MS, Baucheron S, Vizcaino N, Bowden RA, Cloeckaert A. 2002. Single-step purification and evaluation of recombinant BP26 protein for serological diagnosis of Brucella ovis infection in rams. Vet. Microbiol. 87:213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhuri P, Prasad R, Kumar V, Basavarajappa AG. 2010. Recombinant OMP28 antigen-based indirect ELISA for serodiagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Mol. Cell. Probes 24:142–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thavaselvam D, Kumar A, Tiwari S, Mishra M, Prakash A. 2010. Cloning and expression of the immunoreactive Brucella melitensis 28 kDa outer-membrane protein (Omp28) encoding gene and evaluation of the potential of Omp28 for clinical diagnosis of brucellosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seco-Mediavilla P, Verger JM, Grayon M, Cloeckaert A, Marin CM, Zygmunt MS, Fernandez-Lago L, Vizcaino N. 2003. Epitope mapping of the Brucella melitensis BP26 immunogenic protein: usefulness for diagnosis of sheep brucellosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:647–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloeckaert A, Jacques I, Grillo MJ, Marin CM, Grayon M, Blasco JM, Verger JM. 2004. Development and evaluation as vaccines in mice of Brucella melitensis Rev 1 single and double deletion mutants of the bp26 and omp31 genes coding for antigens of diagnostic significance in ovine brucellosis. Vaccine 22:2827–2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossetti OL, Arese AI, Boschiroli ML, Cravero SL. 1996. Cloning of Brucella abortus gene and characterization of expressed 26-kilodalton periplasmic protein: potential use for diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:165–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Junsheng PX, Kairong M, Yuwen J, Yecai X, Jiabo D. 2010. Detection of virulences of B. abortus 2308, B. melitensis M28 and B. suis S1330. Chin. J. Vet. Drug 44:3 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding J, Pan Y, Jiang H, Cheng J, Liu T, Qin N, Yang Y, Cui B, Chen C, Liu C, Mao K, Zhu B. 2011. Whole genome sequences of four Brucella strains. J. Bacteriol. 193:3674–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chand P, Rajpurohit BS, Malhotra AK, Poonia JS. 2005. Comparison of milk-ELISA and serum-ELISA for the diagnosis of Brucella melitensis infection in sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 108:305–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celik AD, Yulugkural Z, Kilincer C, Hamamcioglu MK, Kuloglu F, Akata F. 2012. Negative serology: could exclude the diagnosis of brucellosis? Rheumatol. Int. 32:2547–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rafie-Kolpin M, Essenberg RC, Wyckoff JH., III 1996. Identification and comparison of macrophage-induced proteins and proteins induced under various stress conditions in Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 64:5274–5283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eschenbrenner M, Horn TA, Wagner MA, Mujer CV, Miller-Scandle TL, DelVecchio VG. 2006. Comparative proteome analysis of laboratory grown Brucella abortus 2308 and Brucella melitensis 16M. J. Proteome Res. 5:1731–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Z, Yan F, Ji W, Luo D, Liu X, Xing L, Duan Y, Yang P, Shi X, Lu Z, Wang X. 2011. Identification of immunoreactive proteins of Brucella melitensis by immunoproteomics. Sci. China Life Sci. 54:880–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiwari AK, Kumar S, Pal V, Bhardwaj B, Rai GP. 2011. Evaluation of the recombinant 10-kilodalton immunodominant region of the BP26 protein of Brucella abortus for specific diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18:1760–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]