Abstract

Escherichia coli YggS is a member of the highly conserved uncharacterized protein family that binds pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP). To assist with the functional assignment of the YggS family, in vivo and in vitro analyses were performed using a yggS-deficient E. coli strain (ΔyggS) and a purified form of YggS, respectively. In the stationary phase, the ΔyggS strain exhibited a completely different intracellular pool of amino acids and produced a significant amount of l-Val in the culture medium. The log-phase ΔyggS strain accumulated 2-ketobutyrate, its aminated compound 2-aminobutyrate, and, to a lesser extent, l-Val. It also exhibited a 1.3- to 2.6-fold increase in the levels of Ile and Val metabolic enzymes. The fact that similar phenotypes were induced in wild-type E. coli by the exogenous addition of 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate indicates that the 2 compounds contribute to the ΔyggS phenotypes. We showed that the initial cause of the keto acid imbalance was the reduced availability of coenzyme A (CoA); supplementation with pantothenate, which is a CoA precursor, fully reversed phenotypes conferred by the yggS mutation. The plasmid-borne expression of YggS and orthologs from Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and humans fully rescued the ΔyggS phenotypes. Expression of a mutant YggS lacking PLP-binding ability, however, did not reverse the ΔyggS phenotypes. These results demonstrate for the first time that YggS controls Ile and Val metabolism by modulating 2-ketobutyrate and CoA availability. Its function depends on PLP, and it is highly conserved in a wide range species, from bacteria to humans.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli YggS belongs to a poorly characterized but highly conserved protein family that binds pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP). YggS and its orthologs, which range in molecular mass from 24 to 30 kDa, are highly conserved and are present in almost all kingdoms of life, including bacteria, plants, yeasts, and mammals. This high degree of conservation indicates that YggS plays an important role in cellular functions, but no definitive information is available thus far.

In the E. coli genome, yggS is located at 66.67 min on the genetic map and is in a polycistronic operon that is composed of 5 poorly characterized genes, yggS-yggT-yggU-yggV-yggW (1). A similar genetic localization is also found in the genomes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pantoea sp. strain At-9b. Among the products of these operons, YggT is an integral membrane protein that has no clearly defined function, and its orthologs are found in bacteria and plants. We previously found that the introduction of the plasmid-borne yggT into an E. coli TK2420 strain, which lacks 3 major K+ uptake systems (Kdp, Trk, and Kup) and requires exogenous K+, enabled us to restore cell growth at high osmotic pressure (1). The YggT homologs are required for the biogenesis of the c′ heme in the cytochrome b6f complex in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (2), as well as for the proper distribution of nucleoids in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria (3). The fourth gene product, YggV, exhibits ITP/XTPase activity, and a previous study has suggested that it removes misincorporated bases, such as xanthine or hypoxanthine, from the pool of DNA precursors (4). To date, no functional correlations have been reported between YggS and other gene products in the cluster, which include YggT, YggU, YggV, and/or YggW.

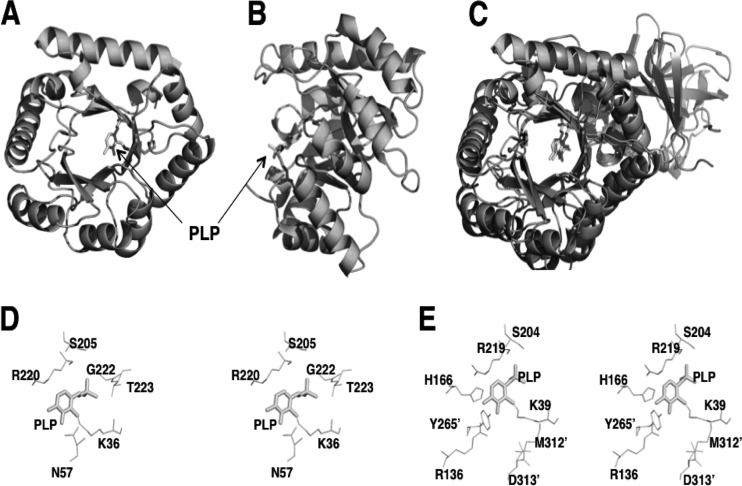

Three-dimensional structures of YggS and the yeast ortholog Ybl036c (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have been solved, and they are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under entries 1W8G (for Ygg proteins) and 1CT5/1B54 (for Ybl036c). They exist as a single-domain and a monomeric molecule, respectively, and exhibit typical (β/α)8-TIM barrel structures (Fig. 1A and B). One mole of PLP is covalently bound via a Lys residue, Lys36 in YggS and Lys49 in Ybl036c, through a Schiff base linkage (Fig. 1). Despite their low sequence identities, the structures of YggS and Ybl036c show striking similarity to that of the N-terminal domain of bacterial alanine racemase (AR) (Fig. 1C) and eukaryotic ornithine decarboxylase. The Z score between Ybl036c and AR of Geobacillus stearothermophilus is 18.6 with a root mean square deviation of 2.7 Å (5). It should be noted that previous studies have suggested that Ybl036c and the ortholog of Bacillus subtilis (YlmE) are amino acid racemases (5, 6). There is, however, no definitive evidence of the proteins' functions; thus, it remains to be elucidated whether they actually catalyze amino acid racemization.

Fig 1.

Structure of YggS and comparison to bacterial AR. A front view (A) and side view (B) of the YggS structure are represented. The PDB code used for YggS is 1W8G. (C) The superposition of the YggS structure onto that of the monomeric structure of G. stearothermophilus AR (PDB entry 1SFT). (D and E) Stereo view of the putative active site of YggS (D) and the active site of AR (E).

This study was initiated to examine the in vitro reactivity of YggS and its orthologs, including S. cerevisiae Ybl036c and Bacillus subtilis YlmE, with various d- and l-amino acids. The results obtained showed that the purified proteins have no in vitro activity, such as racemization against 20 kinds of proteinogenic amino acids and their corresponding d-amino acids. An in vivo study provided the first direct evidence that YggS regulates Ile and Val metabolic pathways in E. coli cells. A yggS-deficient E. coli strain was found to accumulate l-Val with a severely perturbed intracellular amino acid level in the stationary phase. We found that such phenotypes were caused by 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate accumulation. Further studies indicated that the initial consequence of the keto acid imbalance was caused by the attenuation of coenzyme A (CoA) availability. We also demonstrated that the biological function of YggS depends on PLP and is highly conserved in a wide range of species, from bacteria to humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Amino acids, leucine dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus, phosphotransacetylase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and malate dehydrogenase from pig heart were from Wako (Osaka, Japan). KOD-plus ver-2 DNA polymerase was from Toyobo (Osaka, Japan). Citrate synthase (from porcine heart) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Restriction enzymes were purchased from TaKaRa Shuzo (Kyoto, Japan) or New England BioLabs Inc. (Beverly, MA). Oligonucleotides were ordered and purchased from Fasmac (Tokyo, Japan) or Operon Biotechnology (Tokyo, Japan). d-Pantoate was obtained by autoclaving d-pantolactone solution (0.5 M d-pantolactone in 0.5 M KOH) for 20 min at 121°C.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. LB or M9-glucose synthetic medium were used for cell growth. The LB medium contained 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl. The M9-glucose medium consisted of 0.6% Na2HPO4, 0.3% KH2PO4, 0.1% NH4Cl, 0.05% NaCl, 0.2% glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 μM FeSO4, 10 μM CaCl2, and 0.001% thiamine-HCl. Agar (1.5%) was added for solid medium. Ampicillin and kanamycin were added to the LB or the M9-glucose medium when required at a final concentration of 100 and 30 μg/ml, respectively. For the growth test, cells from overnight culture (in LB medium) were washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.5), and inoculated in the M9 medium at a final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.02. Growth of the bacteria was measured as the cell OD600 with shaking at 30°C.

Table 1.

E. coli strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| MG1655 | F− λ− rfb-50 rph-1; mutated in ilvG | Laboratory collection |

| MG1655ΔyggS | F− λ− rfb-50 rph-1 yggS::Kmr; mutated in ilvG | This study |

| XL1-Blue | hsdR17 supE44 recA1 endA1 gyrA46 thi relA1 lac-F′ [proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15::Tn10(Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| BL21 | F− dcm ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal[malB+]K-12 (λS) | Laboratory collection |

| BL21(DE3) star | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm rne131 (DE3) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD13 | Kmr gene with FLP recombination target sequence | 7 |

| pKD46 | λ Red recombinase expression plasmid | 7 |

| pU0 | Control vector (pUC19 containing partial sequence of yggS) | This study |

| pUS | yggS expression vector (expresses YggS-His) | 1 |

| pUSm | pUS containing K36A mutation of YggS | 1 |

| pGEX-4T-1 | Empty vector | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX-4T-3 | Empty vector | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX-yggS | yggS expression (expresses GST-YggS-His) | This study |

| pGEX-ylmE | ylmE expression (expresses GST-YlmE) | This study |

| pGEX-YBL036C | YBL036C expression (expresses GST-ybl036c) | This study |

| pGEX-prosc | PROSC expression (expresses GST-PROSC) | This study |

| pYggS | YggS (C-terminal His tag) expression | This study |

| Primersa | ||

| yggS-H1 | AGCGCCATCGCAGAAGCCATTGATGCCGGGCAGCGTCAATGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC | This study |

| yggS-H2 | TCGTCCGACATTCCCAGAGAGAGCGTGTCGATATGCGGGTATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | This study |

| yggS-pET-fw | CACCATGAACGATATGCGCATAAGCGG | This study |

| yggS-pET-rv | TTAATGGTGATGAGGTGATGTTTTTTAGAGTAATCA | This study |

| yggS-fw | AAAGAATTCAGAAGGAGATCCTCGGAAAATGAACG | This study |

| yggS-rv | AAACTGCAGTTAATGGTGATGATGGTGATGTTTTTTAGAGTAATCACGCGC | This study |

| ybl036c-fw | GGAATTCAGGAGGATTGCAATATGTCCACTGGTATTACTTATGATG | This study |

| ybl036c-rv | AACTCGAGCTAGTGATGGTGGTGATGGTGAATGATTCTAGCTTCATTTTTTGGAGGTC | This study |

| hPROSC-fw | GGAATCCAGAAGGAGATCCTCGGAAAATGTGGAGCTGGAGAGCTGGCAGCATGTC | This study |

| hPROSC-rv | AACTGCAGTCAATGATGGGTGATGATGGTGCTCCTGTGCACCTCCAG | This study |

| ylmE-fw | AAAGAATTCATGCGTGTTGTTGATAATTTACGAC | This study |

| ylmE-rv | AATAGTCGACTCATTGCTGTACACCCCCTG | This study |

Primer sequences are given in 5′ to 3′ orientation.

Genetic manipulation.

The disruption of yggS of E. coli K-12 MG1655 was performed using the λ Red recombinase system described by Datsenko and Wanner (7). A PCR product was generated by using two 60-nucleotide (nt) primers, yggS-H1 and yggS-H2, comprised of 40 nt homologous to the yggS gene and an additional 20 nt complementary to the template plasmid pKD13, which carries the kanamycin resistance gene. The 100-ng sample of the PCR product was purified from the agarose gel and electroporated into wild-type (WT) E. coli MG1655 cells harboring pKD46, which had been grown in LB solid medium containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C. Gene knockout was verified through colony-directed PCR. Construction of pUS (pUC19-yggS) and pUSm has been described previously (1). A control plasmid, pU0, which contains part of the yggS sequence, was obtained by FspI digestion of pUS and then self-ligation (1). pGEX-yggS, pGEX-YBL036C, pGEX-ylmE, and pGEX-prosc are derived from pGEX vector (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and express E. coli yggS, S. cerevisiae YBL036C, B. subtilis ylmE, and Homo sapiens PROSC, respectively. They were constructed as follows. The E. coli yggS gene was obtained by PCR with a set of primers (yggS-fw and yggS-rv) with genomic DNA of E. coli MG1655 as the template. A set of primers (YBL036C-fw and YBL036C-rv) and the chromosomal DNA from S. cerevisiae BY4742 were used for the amplification of the Ybl036c gene. The ylmE gene was amplified with primers ylmE-fw and ylmE-rv. The genomic DNA from B. subtilis NCIB3610 was used for gene amplification. The cDNA of PROSC was amplified using the primes hPROSC-fw and hPROSC-rv. Plasmid pOTB7 containing the full-length PROSC cDNA, which was purchased from Open Biosystems Inc. (plasmid MHS1011; Huntsville, AL), was used as the template. Each of the amplified DNA fragments was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, purified from the agarose gel, and then cloned into pGEX vector. The proteins were expressed in E. coli cells as a fusion with N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST). pYggS was constructed by using Champion pET directional TOPO expression kits (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primer set yggS-pET-fw and yggS-pET-rv and the genomic DNA of E. coli MG1655 were used for the yggS amplification. Plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Protein purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3) star (Invitrogen) carrying pYggS was cultivated in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 30°C. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG; 1 mM) was added to the medium at mid-log phase, and the cells were collected after 12 h of cultivation. All of the following purification steps were performed at 4°C. The cell pellet was suspended in a binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 500 mM NaCl and 80 mM imidazole, pH 7.9) and disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min, the clear lysate was applied to a Ni affinity chromatography equipped with Ni Sepharose 6 fast flow (GE Healthcare, WI). The column was washed with a washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 500 mM NaCl and 80 mM imidazole, pH 7.9), and the purified protein was eluted with an elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 500 mM NaCl and 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.9). The protein was dialyzed with PBS containing 20 μM PLP and redialyzed in the same buffer in the absence of PLP to remove unbound PLP. The purified protein was stored at −80°C until use.

Amino acid pool analysis.

Cells were grown in M9-glucose medium to a final OD600 of 0.5 or 2.0. The cell pellet (∼100 mg) was washed once with the ice-cold PBS and was resuspended in 4-fold cell pellet volumes (∼400 μl) of 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution. After sonication and following incubation for 30 min at 4°C, the cell debris was removed by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C). The TCA was removed from the sample by three extractions with a water-saturated diethyl ether. The samples were stored at −20°C until use. The culture medium supernatant (1 ml) was deproteinized with 200 μl of 30% TCA, and the TCA was removed by 3 extractions with water-saturated diethyl ether. The solution was dried under vacuum, and the resultant pellet was then reconstituted in distilled water. The samples were stored at −20°C until use.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

A 20-μl aliquot of the sample was applied to an amino acid analysis system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Shim-pack amino Na column (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and RF-10A spectrofluorometer after derivatization with O-phtalaldehyde and l-acetylcysteine according to the manufacturer's protocol. Amino acid mixture standard solution (Type H; Wako, Japan) was used for identification and quantification of amino acids. The enantioselective amino acid analysis was performed as described previously (8, 9).

Enzymatic determination of l-Val.

The reaction mixture (final volume, 250 μl) containing 200 mM glycine-KCl-KOH buffer (pH 10.2), 5 mM NAD+, 1 mU leucine dehydrogenase (1 U is defined as the amount of enzyme to produce 1 μmol of NADH from l-leucine in 1 min at 30°C), and the deproteinized culture supernatant was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, the l-Val concentration was estimated as the NADH formation (increase of the A340) over time.

Keto acid analysis.

Intracellular keto acids were extracted from E. coli cells as follows. Mid-log-phase cells (OD600, 0.5; ∼100 mg cells) in M9-glucose medium were suspended in 4 volumes (∼400 μl) of 0.8 M HClO4 and incubated for 5 min at 4°C. The resultant cell suspension was centrifuged for 15 min (11,000 × g, 4°C), and the supernatant was 10-fold diluted. The aliquot (200 μl) was mixed to equal amounts in a solution consisting of 0.7 mM 1,2-diamino-4,5-methylenedioxybenzene (DMB; Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan), 0.7 M HCl, 1.0 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 28 mM Na2S2O4 and incubated for 4 h at 50°C in a dark place. The resultant solution was passed through a 0.45-μm filter device and stored at −80°C until use. The separation and quantification of the derivatized keto acids were performed according to the protocol described by Kato et al. (10).

Determination of total coenzyme A.

The levels of total coenzyme A were determined according to the method previously described by Allred and Guy (11). Briefly, WT and ΔyggS strains were cultivated in M9-glucose medium at 30°C. Cultures were grown to log phase (OD600, ∼0.5), and the cells were collected by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). Cells (∼80 mg) were resuspended in ice-cold PBS and disrupted by the addition of HClO4 to a final concentration of 0.4 M. The suspensions were incubated on ice for 30 min and were vortexed periodically. After centrifugation (20,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C), the resultant supernatant was neutralized with KOH. The reaction solution (1 ml) contained 500 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 50 mM KCl, 20 mM malate, 8 mM lithium acetyl phosphate, 2 mM NAD+, 3 U citrate synthase, 15 U malate dehydrogenase, 8.4 U phosphotransacetylase, and the cell extract. The reaction was performed at 30°C in a cuvette with a 1-cm light path. The rate of NADH formation was measured at 340 nm using a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer.

Enzyme assay.

Crude cell extracts were prepared using mid-log-phase cells (OD600, 0.5) grown in M9-glucose medium. The cells (∼80 mg) were collected by centrifugation and were resuspended in 10 volumes of a disruption buffer (∼800 μl) containing 100 mM potassium phosphate, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 20% glycerol (pH 7.5). The cell suspension was sonicated and centrifuged (20,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C), and the resultant clear lysate was used for the enzyme assay. Protein concentration was determined by the procedure of Bradford with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

(i) Threonine dehydratase activity.

An aliquot of the cell-free lysate (∼125 μg of protein) was added to the reaction mixture containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 40 μM PLP, and 20 mM l-Thr at a final volume of 250 μl. After incubation for 60 min at 30°C, 20 μl of the reaction mixture was withdrawn and diluted to 50 μl. A 50-μl aliquot of 0.1% 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (2,4-DNP; Kanto Chemical Co. Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in 2N HCl was added to the mixture and incubated for 10 min at 25°C. A 100-μl aliquot of ethanol and a 125-μl aliquot of 2N NaOH were mixed, and chromophore formation was allowed to occur. The absorbance at 515 nm of the sample was determined with a Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrophotometer. The amount of 2-ketobutyrate formed was estimated by comparison of the absorbance of known concentrations of 2-ketobutyrate.

(ii) AHAS activity.

Activity of acetohydroxy acid synthase (AHAS) was determined in the reaction mixture containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM pyruvate, 100 μM thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), 100 μM flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and the cell-free lysate (∼300 μg of protein) in a total volume of 500 μl at 30°C. The rate of pyruvate consumption was calculated by monitoring the decrease of the absorbance at 333 nm (ε, 17.5 M cm−1) (12).

(iii) Transaminase B (IlvE) activity.

Activity of branched-chain amino acid transaminase (transaminase B; IlvE) was determined according to the method described by Duggan and Wechsler (13). The standard assay mixture (500 μl) contained 100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 μM PLP, 15 mM α-ketoglutarate, 25 mM l-Val, and the cell extract (0.5 to 1.0 mg/ml), pH 8.0, which was incubated for 30 min at 37°C.

(iv) Transaminase C (AvtA) assay.

Activity of alanine-valine transaminase (transaminase C; AvtA) was determined at 37°C according to the method described previously, with slight modifications (14). The method is based on a different extraction of pyruvate and α-ketoisovaleric acid (KIV). The 500-μl reaction mixture contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM KIV, 10 mM l-Ala, 1 mM PLP, and cell extract (∼1 mg protein). After 30 min of incubation, 50 μl of 20% metaphosphoric acid was added to terminate the reaction. The ensuing procedures were performed according to the protocol described in reference 14.

RESULTS

Overexpression, purification, and in vitro reactivity of YggS.

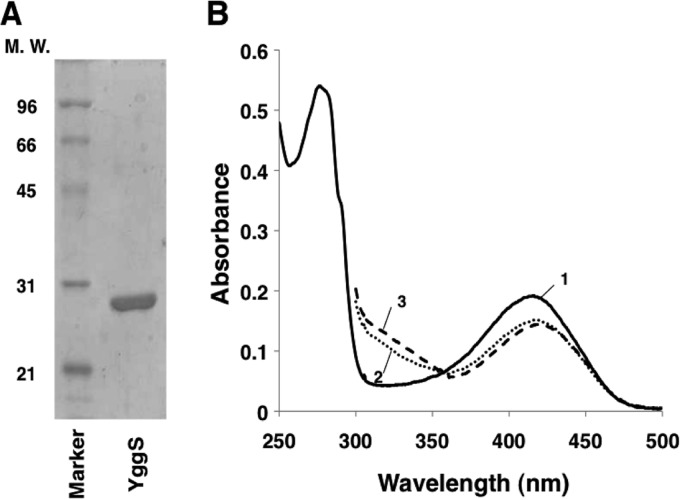

We first constructed an YggS expression vector called pYggS based on the pET system. The recombinant protein with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag was purified from E. coli cells by employing Ni+-affinity chromatography. A single protein band was visible on the SDS-PAGE gel with a molecular mass of approximately 27 kDa; this was compatible with the molecular mass that was calculated from its amino acid sequence (26,610 Da) (Fig. 2A). In the isolated form, the protein solution was yellow and absorbed at 278 and 416 nm with an absorbance ratio (A278/A416) of 2.8 (Fig. 2B). The 416-nm peak decreased with a concomitant increase at approximately 330 nm upon the addition of the Schiff base-reducing agent NaBH4. The Lys36-to-Ala mutation of YggS (YggS-K36A) disappeared from the absorption peak observed at 416 nm (data not shown). These observations confirmed that YggS binds PLP through a Schiff base linkage with Lys36.

Fig 2.

Purity of the recombinant YggS and the UV-visible spectra in the presence or absence of d- and l-Cys. (A) The purified protein was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. MW, molecular weight (in thousands). (B) Absorption spectra of the purified YggS in the absence (line 1) or presence of d-Cys (5 mM; line 2) and l-Cys (5 mM; line 3). These spectra were recorded in PBS buffer at a protein concentration of 31 μM.

The majority of PLP-dependent enzymes are involved in amino acid metabolism. Therefore, enzymatic activities of YggS, such as racemization, decarboxylation, transamination, and deamination, were investigated by incubating it with each of 20 kinds of proteinogenic amino acids and their corresponding d-amino acids. Unlike as suggested elsewhere (5, 6), no racemase activity was detected in this study. In addition, the presence of YggS neither decreased the reactant amino acids nor yielded new amino acids, which was confirmed through HPLC analyses and which indicates that YggS does not show in vitro activity toward these amino acids under the conditions examined (data not shown). Similar analyses were also performed with recombinant Ybl036c, YlmE, and PROSC, which were purified from E. coli XL1-Blue cells that harbored pGEX-YBL036C, pGEX-ylmE, and pGEX-prosc, respectively. However, no enzymatic activity was detected for any of the proteins.

In order to examine the binding of amino acids to the protein, we individually added the 20 kinds of proteinogenic amino acids and their corresponding d-amino acids to YggS and then examined the changes in the visible spectra of the protein. Almost no spectral changes occurred with the amino acids, which suggests that YggS did not react with them. Two exceptions were d- and l-Cys, which affected the visible spectra of YggS (Fig. 2B). The addition of d- and l-Cys decreased the absorption at around 420 nm in a time-dependent manner, with the concomitant appearance of a new peak at 330 nm. This phenomenon likely was observed because of the formation of nonreactive thiazolidine, which absorbs at approximately 330 nm. Similar phenomena have been observed for some other PLP-dependent enzymes (15).

Inhibitory effect of ΔyggS culture supernatant.

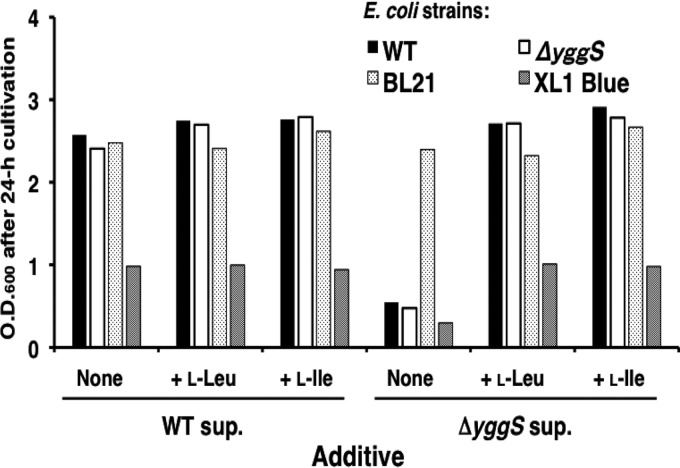

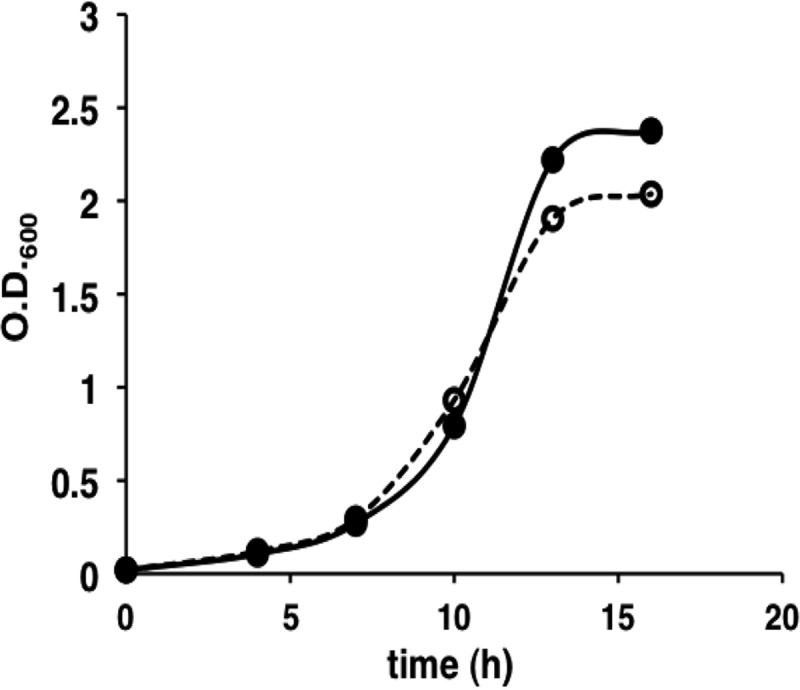

To analyze the biological role of YggS, a yggS-deficient E. coli strain (ΔyggS) was constructed by using homologous recombination according to the protocol developed by Datsenko and Wanner (7). The ΔyggS strain grew well both in rich (LB) and minimal salt (M9-glucose) media. Although no apparent differences were observed in the growth rates between the WT and ΔyggS E. coli strains in the LB medium, the ΔyggS strain exhibited slight growth retardation in the M9-glucose medium (Fig. 3). In the log phase, the initial rate of glucose consumption was almost the same for the 2 strains (data not shown). This suggested that some toxic metabolite(s) was produced by the ΔyggS strain. To examine the toxicity of the ΔyggS culture supernatant, 24-h-old culture supernatant was added to freshly prepared M9-glucose medium, and the cell growth of WT and ΔyggS strains was examined after 24 h of cultivation by measuring their OD600 values. As shown in Fig. 4, cell growth was severely impaired by the ΔyggS mutant culture supernatant. In contrast, the culture supernatant of WT (Fig. 4) and ΔyggS/pUS (ΔyggS cells that expressed complementary yggS; data not shown) strains did not show inhibitory effects, which indicated the presence of a toxic compound in the ΔyggS culture supernatant. It should be noted that the toxic effect was manifested regardless of the presence of yggS; growth of both WT and ΔyggS strains was inhibited by the ΔyggS culture supernatant (Fig. 4). Thus, the toxic molecule was unlikely to be the substrate of YggS. Moreover, this molecule should be a nonprotein compound, because the autoclaved culture supernatant of the ΔyggS mutant retained its inhibitory effect on E. coli cells (data not shown).

Fig 3.

Growth of WT and ΔyggS strains in the M9-glucose medium. Wild-type (•) and ΔyggS (○) strains were cultivated in the M9-glucose medium at 30°C. The OD600 was determined 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16 h after inoculation.

Fig 4.

Inhibitory effect of ΔyggS mutant strain culture supernatant. Wild-type E. coli MG1655 (shown as the WT), E. coli MG1655 ΔyggS mutant (ΔyggS), E. coli BL21 (BL21), and E. coli XL1-Blue (XL1 blue) were grown in the M9-glucose medium containing 24-h-old WT or ΔyggS culture supernatant (sup.). The 24-h-old culture supernatants were filter sterilized and added to a freshly prepared M9-glucose medium at a final concentration of 25%. l-Ile and l-Leu were added at a final concentration of 0.1 mM. After 24 h of cultivation, the OD600 was determined.

l-Valine accumulation in the stationary-phase medium of the ΔyggS strain.

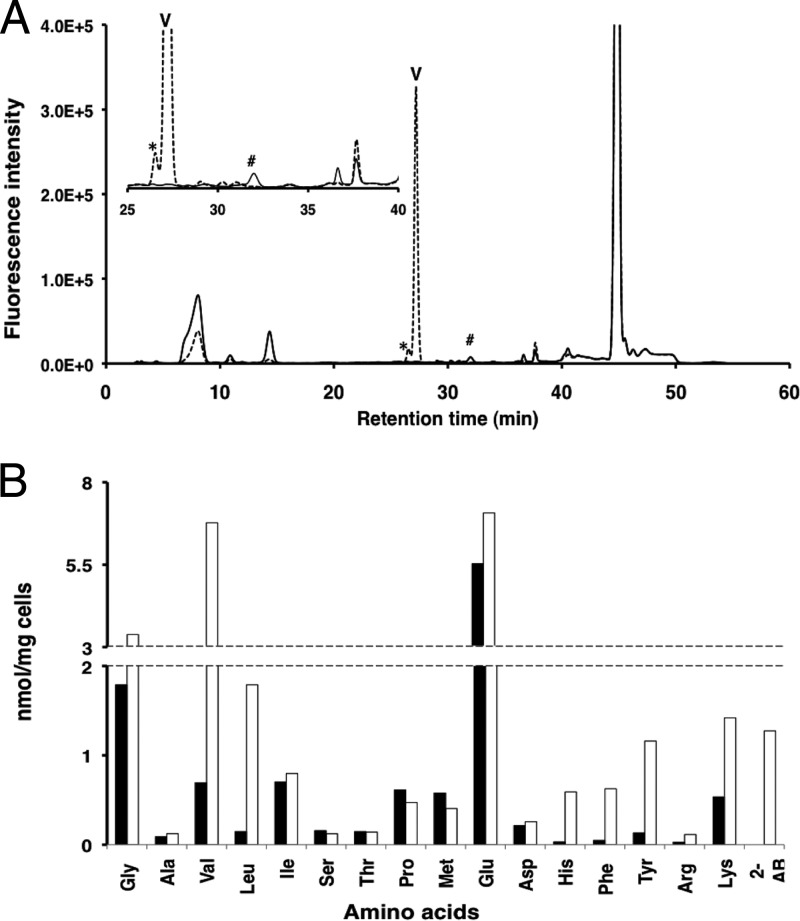

Because YggS is a PLP-binding protein, we were able to make a simple prediction about whether the toxic metabolite(s) was an amino acid or its related compound. For this purpose, we performed an amino acid analysis of the 24-h-old culture supernatant. We found that the ΔyggS culture supernatant contained a significant amount of Val (Fig. 5A). The l-Val concentration was 0.7 μM for the WT culture supernatant and 110 μM for the ΔyggS culture supernatant. Enantioselective amino acid analysis confirmed that the amino acid is l-Val. Extracellular l-Val accumulated in a time-dependent manner and reached a concentration of approximately 120 μM after inoculation for 16 h. The ΔyggS culture supernatant also contained relatively high levels of 2-aminobutyrate, which hardly accumulated in the parental strain (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

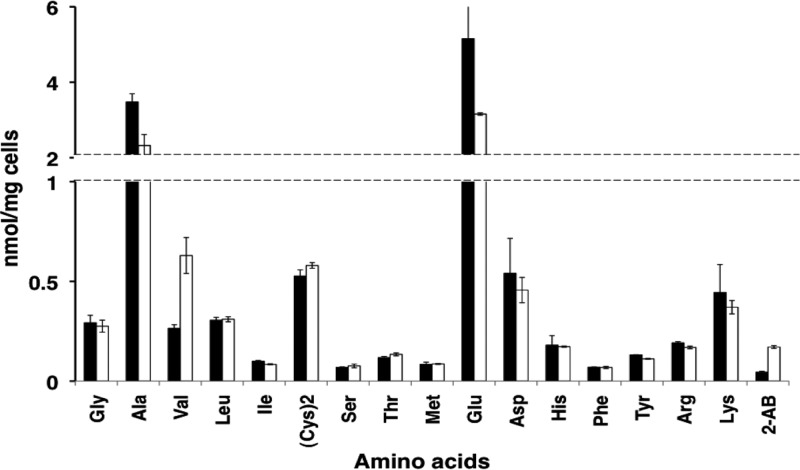

(A) Elution profile of extracellular amino acid at the stationary phase. Wild-type and ΔyggS mutant strains were grown in M9-glucose medium at 30°C. The stationary-phase culture supernatants were collected, deproteinized, and subjected to amino acid analysis. The HPLC chromatograms generated by the amino acid analysis are shown (wild-type, solid line; ΔyggS mutant, broken line). The inset graph shows an expansion of the retention time from 25 to 40 min. The extracellular l-Val (V) concentration was 0.7 and 110 μM in the WT and ΔyggS mutant culture supernatant, respectively. The ΔyggS mutant produced 2-aminobutyrate (*), and only the WT accumulated extracellular Nle (#). (B) Intracellular amino acid composition of stationary-phase cells. Both WT (closed bar) and ΔyggS (open bar) strains were grown in M9-glucose medium at 30°C. After 24 h of cultivation, the concentrations of intracellular amino acids were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

The inhibitory effect of exogenous l-Val against the growth of E. coli K-12 cells is a well-known phenomenon. l-Val inhibition in E. coli K-12 is due to the loss of 1 of 3 acetohydroxy acid synthases (AHAS II). AHAS is an enzyme that converts 2 pyruvate molecules into an α-acetolactate during l-Val biosynthesis and condenses one pyruvate plus one 2-ketobutyrate to yield an α-aceto-hydroxybutyrate during l-Ile biosynthesis. The genome of E. coli K-12 contains 3 AHAS genes (AHAS I, II, and III), but the l-Val-insensitive AHAS (AHAS II) gene is inactivated. It is reported that the in vitro AHAS activity of E. coli K-12 is inhibited up to 85 to 90% by treatment with 1.5 mM l-Val, and that growth of E. coli K-12 is completely blocked with 0.1 mM l-Val (16–18).

To determine whether growth inhibition due to the ΔyggS culture supernatant reflected the accumulation of l-Val, the growth of 2 classes of E. coli strains, (i) E. coli MG1655 and E. coli XL1-Blue carrying a nonfunctional AHAS II and (ii) E. coli BL21 possessing the functional enzyme, were compared to the 24-h-old culture supernatant. As shown in Fig. 4, the growth of both E. coli MG1655 and E. coli XL1-Blue were severely inhibited by the ΔyggS culture supernatant. In contrast, the growth of E. coli BL21 was unchanged with the ΔyggS culture supernatant. Inclusion of l-Ile and l-Leu, which alleviate l-Val toxicity, reduced the inhibitory effect of the ΔyggS supernatant (Fig. 4). These results validated our hypothesis that the inhibitory effect stemmed, in part, from l-Val.

Effect of yggS mutation on intracellular amino acids and keto acids.

Intracellular amino acid analysis using stationary-phase cells revealed that, compared to the WT, the ΔyggS strain accumulates l-Val up to 10-fold (Fig. 5B). In addition to l-Val, the ΔyggS strain overproduced l-Leu, l-His, l-Phe, l-Tyr, and 2-aminobutyrate (Fig. 5B). The concentrations of other intracellular amino acids, such as l-Ala, l-Ile, l-Ser, l-Thr, l-Pro, l-Met, l-Glu, and l-Asp, were unchanged in the ΔyggS strain (Fig. 5B). Such l-Val overproduction suggested that the yggS mutant also overproduced l-Val during the log phase. Amino acid analysis using log-phase cells, however, revealed that the ΔyggS strain accumulated l-Val at a level that was much lower than we expected (∼2.4-fold) (Fig. 6). In contrast, a considerable amount of 2-aminobutyrate was detected in the mutant strain. This amino acid, which also was detected in the ΔyggS strain during the stationary phase (Fig. 5A and B), was accumulated more than 4-fold in the log-phase ΔyggS mutant cells (Fig. 6). Almost all of the other amino acids, such as l-Ile, l-Leu, l-Asp, l-Thr, l-Ser, Gly, l-Met, l-Ile, l-Leu, l-Tyr, l-Phe, l-His, l-Lys, and l-Arg, remained largely unchanged in the mutant strains (Fig. 6). The intracellular content of l-Glu and l-Ala was slightly affected in the mutant strain and was ∼0.6-fold compared to that of the WT (Fig. 6). These results suggest that l-Val and 2-aminobutyrate metabolism were specifically affected by the yggS mutation.

Fig 6.

Intracellular amino acid composition of the log-phase WT (closed bar) and ΔyggS (open bar) strains. Both WT and ΔyggS strains were grown in M9-glucose medium at 30°C. The log-phase cells (OD600, 0.5) were collected and used for the amino acid analysis. 2-AB, 2-aminobutyrate.

l-Val originates exclusively from pyruvate, and 2-aminobutyrate is produced from 2-ketobutyrate; hence, we quantified the levels of intracellular keto acids, including pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate, with the fluorescent labeling agent 1,2-diamino-4,5-methylenedioxybenzene as previously described (10). This experiment revealed that the log-phase ΔyggS cells accumulated 2-ketobutyrate at a more than 6-fold higher level (5.0 pmol/mg) than the WT (0.8 pmol/mg) (Table 2). The pyruvate concentration was slightly higher in the mutant cells. The concentrations of 2-ketoglutarate and glyoxylate were unchanged in ΔyggS cells (Table 2). These results indicate that in the log phase, 2-ketobutyrate metabolism is significantly affected by the yggS mutation.

Table 2.

Intracellular keto acid content of WT and ΔyggS cells at log phase

| Strain | Keto acid contenta (pmol/mg cells) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate | α-Ketoglutarate | 2-Ketobutyrate | Glyoxylate | |

| Wild type | 238 ± 82 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| ΔyggS mutant | 290 ± 43 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

Data are averages from triplicate experiments.

Aminobutyric acid and/or 2-ketobutyrate contributes to l-Val production.

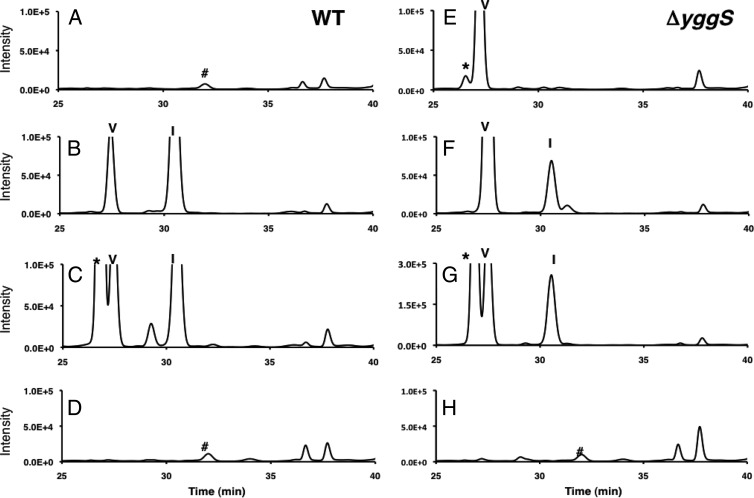

Previous studies have shown that 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate inhibit cell growth and induce the expression of a number of enzymes that are required for Ile and Val biosynthesis (19–21). Therefore, we examined whether endogenously produced 2-ketobutyrate and the resulting 2-aminobutyrate affect l-Val productivity. The toxicity of these compounds was mimicked by adding them to the culture medium at a final concentration of 1 mM. Both WT and ΔyggS mutant cells were cultivated in the medium, and the extracellular amino acid content was analyzed after overnight cultivation (∼24 h). As shown in Fig. 7, more l-Val was excreted from ΔyggS mutants by the additives: the concentration of extracellular l-Val was at 58 μM without the additive, 125 μM with 2-ketobutyrate, and 102 μM with 2-aminobutyrate, respectively (Fig. 7F and G). More importantly, treatment of the WT with the 2 compounds resulted in l-Val secretion (Fig. 7B and C). Upon the addition of 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate, the WT produced extracellular l-Val up to 23 and 37 μM, respectively (Fig. 7B and C). Similar experiments were performed with l-Ile, l-Thr, l-Leu, l-Asp, l-Ala, Gly, and l-Met. However, these amino acids neither induced l-Val secretion in the WT nor alleviated l-Val excretion from the ΔyggS strain (data not shown). These results indicate that l-Val overproduction was due in part to the accumulation of endogenously produced 2-ketobutyrate and the resulting 2-aminobutyrate.

Fig 7.

Effect of 2-ketobutyrate, 2-aminobutyrate, and pantothenate on l-Val productivity. The HPLC chromatograms generated by amino acid analysis of the stationary-phase culture supernatant of WT (left) and ΔyggS mutant (right) strains cultivated alone (A and E) or in the presence of 1 mM 2-ketobutyrate (B and F), 1 mM 2-aminobutyrate (C and G), and 1 mM pantothenate (D and H). The cells were grown in the M9-glucose medium at 30°C. Symbols: *, 2-aminobutyrate; V, valine; I, isoleucine; #, norleucine.

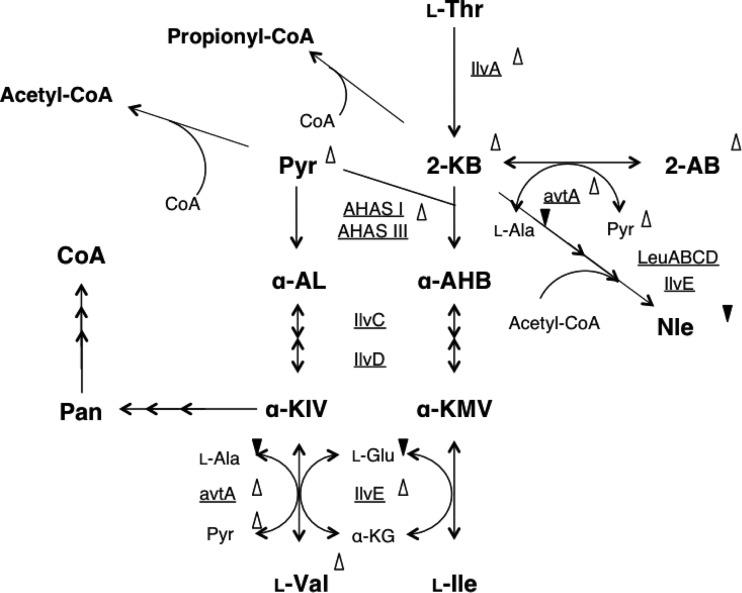

As suggested, 2-ketobutyrate affected the levels of enzymes that are involved in Ile-Val metabolism. The levels of all 4 enzymes involved in Ile-Val metabolism (i.e., AHAS, threonine dehydratase, transaminase B, and transaminase C; Fig. 8 depicts the reactions that are catalyzed by each enzyme) were quantified using log-phase cells (Table 3). Enzyme tests showed that the level of threonine deaminase (IlvA), which produces 2-ketobutyrate from l-Thr as a starting molecule of l-Ile biosynthesis, was 2.6 times higher in the yggS mutant (50.0 nmol · min−1 · mg−1) than in the WT (18.6 nmol · min−1 · mg−1). AHAS activity in the ΔyggS mutant (66.3 nmol · min−1 · mg−1) was elevated by approximately 1.6-fold compared to that of the WT (41.1 nmol · min−1 · mg−1). Transaminase B (IlvE), which catalyzes the last step in the synthesis of branched amino acids, was slightly stimulated in the ΔyggS mutant (∼1.3-fold) compared to the WT. The level of transaminase C (alanine-valine transaminase; AvtA), which is responsible for the synthesis of l-Val and 2-aminobutyrate (14), was elevated 2.4-fold in the strain that lacked yggS. Derepression of the Ile-Val metabolic enzymes by the accumulated 2-ketobutyrate was probably the main cause of the ΔyggS phenotypes.

Fig 8.

Schematic view of the l-Ile and l-Val metabolic pathways in E. coli. Metabolites and enzymes (underlined) in Ile and Val metabolism are shown. The symbols (Δ or ▼) indicate an increase (Δ) or decrease (▼) in the level of the compound or the enzyme in log phase. 2-AB, 2-aminobutyrate; 2-KB, 2-ketobutyrate; Pyr, pyruvate; Pan, pantothenate; α-AL, α-acetolactate; α-AHB, α-aceto-α-hydroxybutyrate; α-KMV, α-keto-β-methylvalerate; α-KIV, α-ketoisovalerate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate.

Table 3.

Levels of enzymes in Ile and Val metabolism of WT and ΔyggS cells at log phase

| Enzyme | Level (nmol/min/mg protein) ina: |

|

|---|---|---|

| WT | ΔyggS mutant | |

| Threonine dehydratase (IlvA) | 18.6 ± 2.4 | 50.0 ± 2.8 |

| Acetolactate synthase (AHAS) | 41.1 ± 1.9 | 66.3 ± 5.5 |

| Transaminase B (IlvE) | 12.8 ± 0.4 | 16.3 ± 1.0 |

| Transaminase C (AvtA) | 61.3 ± 2.5 | 148 ± 3.4 |

Data are averages from triplicate experiments.

yggS mutation affects coenzyme A availability.

The results presented above strongly suggest that 2-ketobutyrate accumulation accounts for the ΔyggS phenotypes. It would be helpful for us to determine the initial cause of the 2-ketobutyrate accumulation. A careful review of the amino acid analysis results revealed that the culture supernatant of ΔyggS cells hardly accumulated the nonproteinogenic amino acid norleucine (Nle; Fig. 5A, inset, and 7A and E). In E. coli, Nle is synthesized from 2-ketobutyrate by chain elongation through the action of the l-Leu biosynthetic enzymes 2-isopropylmalate synthase (LeuA), isopropylmalate isomerase (LeuCD), and 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (LeuB), and it follows transamination (IlvE) (Fig. 8). The ΔyggS strain possessed a considerable amount of 2-ketobutyrate as an Nle precursor (Table 2), and all of the enzymes that are involved in Nle (Leu) synthesis seemed to be fully active, since the l-Leu content was elevated rather than decreased in the mutant strain. These results and the fact that, in addition to 2-ketobutyrate, 2 mol acetyl-CoA is required for 1 mol Nle suggest that acetyl-CoA availability is compromised in ΔyggS cells. It is known that exogenous acetate is converted to acetyl-CoA from acetate, CoA, and ATP by acetyl-CoA synthetase. Acetate was added to the M9-glucose medium at final concentrations of 1 and 2 mM, and then extracellular l-Val was assayed in a ΔyggS strain. The exogenous acetate did not restore the l-Val accumulation in a ΔyggS strain (data not shown). These observations suggest that the levels of CoA pools are also lowered in the ΔyggS strain.

Based on these observations, we supplemented the M9-glucose medium with pantothenate, which is a CoA precursor, and the excretion of l-Val and Nle was quantified using the stationary-phase culture supernatant. Upon supplementation, the ΔyggS mutant was allowed to grow with Nle but without l-Val excretion (Fig. 7H). It should be noted that in the presence of pantothenate, the contents of the other extracellular amino acids of the ΔyggS strain were almost identical to those of the WT (Fig. 7A, D, and H). These results indicate that pantothenate fully complemented the phenotypes that were conferred by the yggS mutation. The pantothenate (and CoA) limitation seems to have arisen from the limitation of pantoate but not of β-alanine. Addition of 1 mM pantoate was effective to decrease the l-Val excretion. β-Alanine supplementation did not affect l-Val productivity in ΔyggS cells (data not shown).

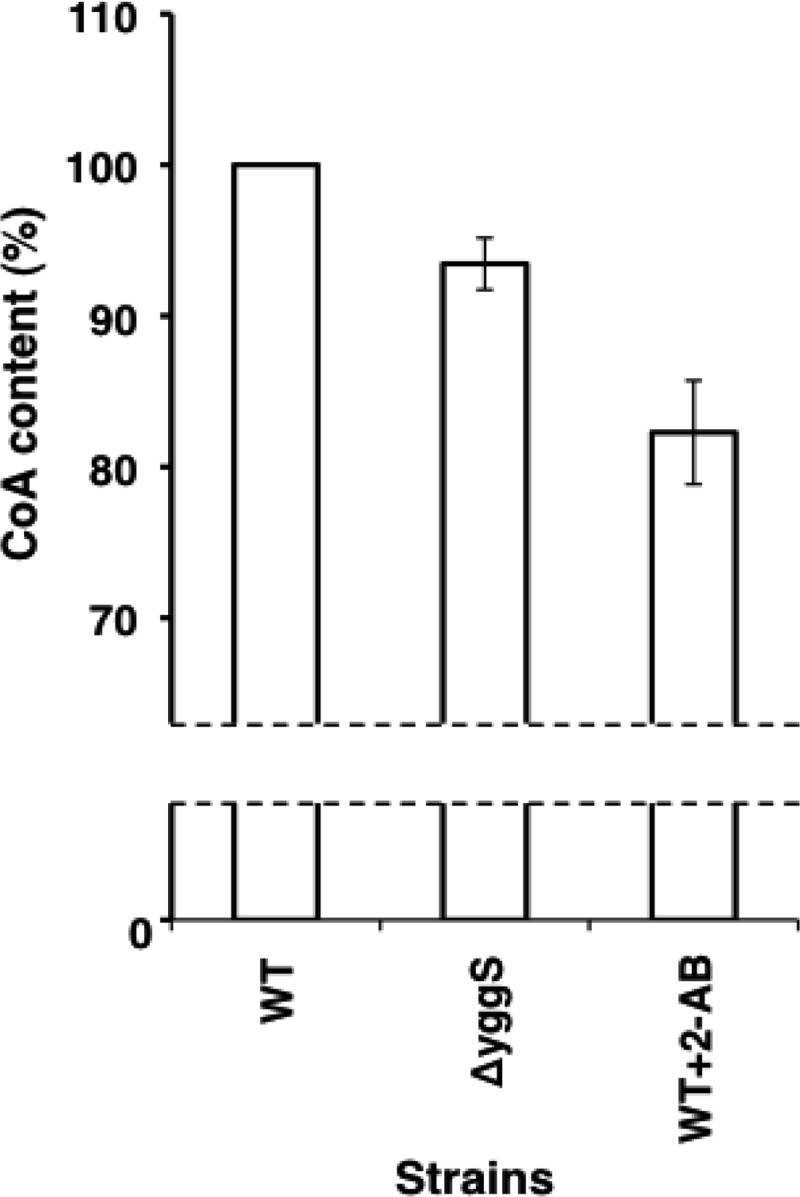

Finally, we determined the intracellular CoA levels in the ΔyggS mutant according to the protocol of Allred and Guy (11). We found that the total CoA levels were ∼10% lower in ΔyggS cells than in WT cells (Fig. 9). The reduced availability of CoA (and/or pantothenate) may have caused pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate accumulation by decreasing the fluxes of these keto acids to acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA. These observations strongly suggest that the primary cause of the ΔyggS phenotypes was the attenuation of CoA availability.

Fig 9.

Total CoA levels in WT and ΔyggS mutant strains. Strains were grown using M9-glucose medium at 30°C. Total CoA levels were quantified according the protocol described in Materials and Methods. 2-Ketobutyrate was added to the medium at a final concentration of 0.1 mM.

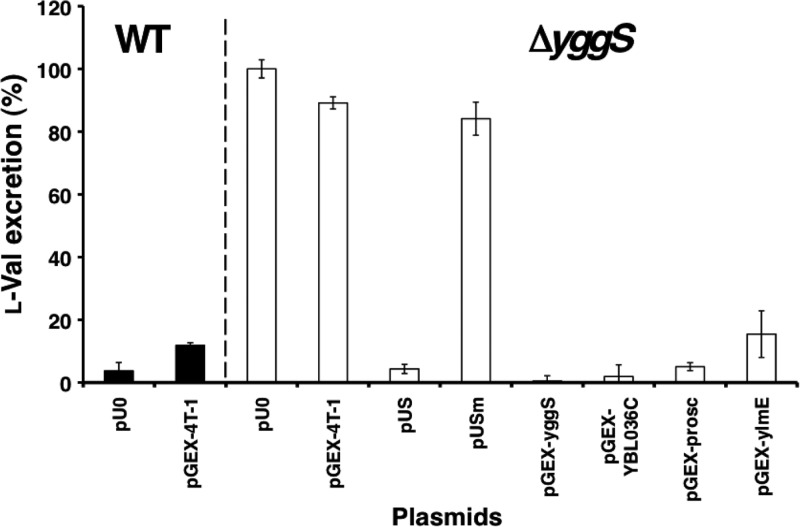

Complementation of the ΔyggS phenotype with the homolog.

In order to investigate the functional conservation of the YggS protein family, we constructed a series of plasmids that expressed YggS (pGEX-yggS) and the orthologs of humans (PROSC and pGEX-prosc), S. cerevisiae (Ybl036c and pGEX-YBL036C), and B. subtilis (YlmE and pGEX-ylmE). These proteins were expressed as fusion proteins with N-terminal glutathione S-transferase. The sequence identities of PROSC, Ybl036c, and YlmE with YggS are 29, 28, and 27%, respectively. The plasmids that encoded these fusion proteins were transferred into the yggS mutant, and the resulting strains were subsequently cultivated in M9-glucose medium. After overnight cultivation, l-Val accumulation in the culture supernatant was enzymatically estimated using leucine dehydrogenase. The yggS mutants that harbored pUS, pGEX-yggS, pGEX-prosc, pGEX-YBL036C, and pGEX-ylmE did not produce extracellular l-Val (Fig. 10). In contrast, the ΔyggS mutant that harbored the control vector (pU0 and pGEX-4T-1) and pUSm, which encodes a mutant YggS protein (YggS-K36A) that lacks PLP binding activity, continued to excrete l-Val into the culture medium (Fig. 10). The intracellular amino acids compositions of ΔyggS cells that harbored pUS, pGEX-yggS, pGEX-prosc, pGEX-YBL036C, and pGEX-ymlE were almost identical to that of the WT. These observations indicate that these orthologs perform the same function as YggS in E. coli and that the binding of PLP is essential for protein function.

Fig 10.

Effect on l-Val productivity of the yggS mutation and the introduction of YggS orthologs. The WT harboring a control vector (pU0 and pGEX-4T-1) and the ΔyggS strain harboring pU0, pGEX-4T-1, pUS, pUSm, pGEX-yggS, pGEX-YBL036C, pGEX-prosc, or pGEX-ylmE were cultivated in M9-glucose medium at 30°C. pUSm expresses a YggS mutant (K36A) lacking PLP binding ability. The l-Val concentration of the stationary-phase culture supernatant was estimated with leucine dehydrogenase as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

YggS and its orthologs show no amino acid racemase activity.

YggS is a member of a highly conserved protein family that has no definite physiological function. YggS binds 1 mol of PLP and exhibits single-domain and monomeric structures that are very similar to the N-terminal domain of bacterial AR (Fig. 1C). The special arrangement of residues around PLP also closely resembles that of AR (Fig. 1D and E). At the same time, there is a critical difference is the residue at the si face of PLP. AR possesses a conserved Tyr residue at the si face of PLP (Tyr265′ in G. stearothermophilus, which originated from another polypeptide). On the other hand, YggS has no residues that interact from the si side of PLP; therefore, the PLP is solvent exposed (Fig. 1B). It is noteworthy that in a previous study by Eswaramoorthy et al., Ybl036c from S. cerevisiae displayed d-Ala to l-Ala racemase activity in vitro (5). In addition, another recent report by Kolodkin-Gal et al. shows that a ylmE and racX (a homolog of bacterial aspartate racemase) double-knockout strain of B. subtilis 3610 (ΔylmE ΔracX) shows blocked d-Tyr accumulation in the culture medium and the cell wall (6).

Thus, we obtained recombinant proteins of YggS, YlmE, Ybl036c, and PROSC and examined their in vitro reactivities with 20 kinds of proteinogenic amino acids and their corresponding d-amino acids. This experiment revealed that these proteins displayed no in vitro reactivity toward the amino acids, including Ala and Tyr racemization. This was not surprising, because they lack the residue that is approached from the si side of PLP. Generally, the racemization of an amino acid requires α-proton abstraction and subsequent reprotonation at the opposite face where α-proton abstraction occurs (22). To achieve this, PLP-dependent amino acid racemases, such as AR and eukaryotic serine racemase (SR), are equipped with 2 catalytic residues that are situated at the re and si faces of the PLP plane, respectively. AR possesses an essential Tyr residue (Tyr265′ in G. stearothermophilus) that abstracts and donates a proton of l-Ala (23–25). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe SR, Lys57 and Ser82 play vital roles in serine racemization (26). Therefore, if YggS catalyzes amino acid racemization, a residue at the si face of PLP that is provided by another polypeptide is probably required. To examine whether YggS catalyzes in vivo racemase activity, we constructed an E. coli strain that lacked 2 alanine racemases (Δalr-Δdad) and displayed d-Ala auxotrophy, and then we introduced pUS into it. We found that the E. coli strain (Δalr Δdad yggS+) still required d-Ala for cell growth (data not shown). This disputes the possibility that YggS catalyzes in vivo alanine racemization.

2-Ketobutyrate is the primary cause of yggS phenotypes.

In vivo studies demonstrated that yggS affects Ile and Val metabolism. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the biological functions of the YggS protein family. During the stationary phase, the amino acid pool of the ΔyggS mutant was dramatically changed compared to that of the WT and reflected the excretion of a considerable amount of l-Val (Fig. 5A). Elevated levels of pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate were also detected in the mutant strain. This indicates that yggS plays important roles in the amino acid and keto acid homeostasis. Measurement of intracellular amino acids and the keto acids using the log-phase cells revealed that the ΔyggS mutant produced a considerable amount of 2-ketobutyrate and its aminated compound, 2-aminobutyrate. l-Val was slightly accumulated in the mutant, but this occurred at a level that was much lower than we expected. In E. coli W and Salmonella Typhimurium that have been supplemented with 2-ketobutyrate and/or 2-aminobutyrate, derepression (i.e., increased levels) of AHAS, transaminase B (IlvE), dihydroxy acid dehydrase (IlvD), and/or IlvA occurs (19–21). Kisumi et al. reported a similar situation, whereby a high concentration of l-Val was excreted into the culture medium for a 2-aminobutyrate-resistant mutant strain of Serratia marcescens (27). These observations led us to hypothesize that 2-ketobutyrate and/or 2-aminobutyrate accumulation is the primary cause of the stationary-phase phenotypes of the ΔyggS mutant. As expected, supplementation with 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate induced l-Val production both for the WT and ΔyggS strain. Because 2-aminobutyrate is synthesized from 2-ketobutyrate, 2-ketobutyrate imbalance is probably the key for l-Val overproduction.

Reduced CoA availability may affect the accumulation of 2-ketobutyrate.

2-Ketobutyrate is mainly produced by IlvA and consumed by AHAS in E. coli. Both the elevation of its biosynthesis and defects in its catabolism can cause 2-ketobutyrate accumulation. Because the intracellular concentrations of l-Ile and l-Leu of the ΔyggS strain were unchanged during the log phase, the latter possibility can be ruled out. In contrast, the elevation in IlvA activity in the yggS mutant could be a reason for the excess 2-ketobutyrate. However, as described above, 2-ketobutyrate and 2-aminobutyrate can stimulate Ile-Val enzymes, including IlvA (19–21, 27). In addition, we found that supplementation with l-Ile and l-Leu, which reduce IlvA activity through allosteric inhibition, could not reverse l-Val secretion in the ΔyggS strain. These observations suggest that the derepression of IlvA is not the primary cause but the result of excess 2-ketobutyrate.

In contrast, we provide a plausible explanation for the keto acid accumulation, which is the attenuation of CoA availability. A first hint about the cause of 2-ketobutyrate accumulation evolved from the observation that the ΔyggS strain hardly accumulated Nle. We showed that total CoA levels were ∼10% less in a ΔyggS strain than those in the WT, and the supplementation with pantothenate, which is a CoA precursor, was very effective in reversing the stationary-phase phenotypes of the ΔyggS strain (Fig. 7 and 9). A decrease in CoA availability is assumed to prevent the efficient conversion of pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate to acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA, respectively, thereby leading to pyruvate and 2-ketobutyrate accumulation. A similar situation was observed by Blombach et al. and Valle et al. (28, 29). They recently reported that the inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (ΔaceE), which catalyzes the transformation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, led to pyruvate accumulation and l-Val excretion in Corynebacterium glutamicum and E. coli (28, 29). Radmacher et al. showed that a C. glutamicum ΔilvA ΔpanBC strain with plasmid-borne ilvBNCD could overproduce l-Val under pantothenate-limiting conditions (30).

On the other hand, we cannot rule out the possibility that the pantothenate and/or CoA limitation stems from the excess 2-ketobutyrate. Powers et al. and Primerano et al. previously suggested that CoA synthesis was compromised by 2-ketobutyrate accumulation by demonstrating that 2-ketobutyrate is a competitive substrate for ketopantoate hydroxymethyltransferase, which is the first enzyme in pantothenate biosynthesis, in E. coli K-12 and S. Typhimurium (31, 32). Accordingly, we found that 2-ketobutyrate significantly lowers the intracellular CoA levels in E. coli (Fig. 9). Therefore, it is necessary to determine the molecular basis of YggS-mediated 2-ketobutyrate accumulation and CoA limitation.

YggS function depends on PLP and is highly conserved in various species.

In an attempt to investigate the functional conservation of the YggS protein family, we found that all of the ΔyggS strains that expressed yggS or its orthologs (of B. subtilis, S. cerevisiae, and humans) grew without l-Val overproduction (Fig. 10). In contrast, YggS-K36A expression did not affect the l-Val productivity of ΔyggS cells (Fig. 10). This observation led us realize that the in vivo function of YggS is highly conserved in a wide range of species, from bacteria to humans, and it depends on PLP. As described above, YggS and its orthologs (PROSC, Ybl036c, and YlmE) share ∼30% sequence identity. However, their highly conserved residues are located near the PLP (data not shown); therefore, they lack conservation of the protein surface. This finding suggests that YggS function is not mediated by protein-protein interactions.

Valle et al. showed that biofilms of E. coli and other Gram-negative bacteria accumulate high levels of Val under stationary-phase-like conditions (29). 2-Ketobutyrate is known to regulate the phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) in amino acid starvation and to be served as an alarmone to govern the shift from anaerobic to aerobic growth (33). ylmE of B. subtilis is reported to be involved in biofilm disassembly (6). These pieces of evidence suggest to us that yggS and the orthologs play a regulatory role under specific conditions, such as low nutrients, and within biofilm by valine or 2-ketobutyrate signaling.

Further studies may shed light on the conserved processes that are mediated by this unique PLP-dependent protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) 24780098 (to T.I.) and by funding from the Takano Life Science Research Foundation and the Towa Foundation for Food Research (to T.I.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Ito T, Uozumi N, Nakamura T, Takayama S, Matsuda N, Aiba H, Hemmi H, Yoshimura T. 2009. The implication of YggT of Escherichia coli in osmotic regulation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73:2698–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuras R, Saint-Marcoux D, Wollman FA, de Vitry C. 2007. A specific c-type cytochrome maturation system is required for oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:9906–9910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabeya Y, Nakanishi H, Suzuki K, Ichikawa T, Kondou Y, Matsui M, Miyagishima SY. 2010. The YlmG protein has a conserved function related to the distribution of nucleoids in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. BMC Plant Biol. 10:57. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw JS, Kuzminov A. 2003. RdgB acts to avoid chromosome fragmentation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1711–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eswaramoorthy S, Gerchman S, Graziano V, Kycia H, Studier FW, Swaminathan S. 2003. Structure of a yeast hypothetical protein selected by a structural genomics approach. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolodkin-Gal I, Romero D, Cao S, Clardy J, Kolter R, Losick R. 2010. D-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science 328:627–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito T, Hemmi H, Kataoka K, Mukai Y, Yoshimura T. 2008. A novel zinc-dependent D-serine dehydratase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 409:399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T, Murase H, Maekawa M, Goto M, Hayashi S, Saito H, Maki M, Hemmi H, Yoshimura T. 2012. Metal ion dependency of serine racemase from Dictyostelium discoideum. Amino Acids 43:1567–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato S, Kito Y, Hemmi H, Yoshimura T. 2011. Simultaneous determination of D-amino acids by the coupling method of D-amino acid oxidase with high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879:3190–3195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allred JB, Guy DG. 1969. Determination of coenzyme A and acetyl CoA in tissue extracts. Anal. Biochem. 29:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasegawa S, Uematsu K, Natsuma Y, Suda M, Hiraga K, Jojima T, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2012. Improvement of the redox balance increases l-valine production by Corynebacterium glutamicum under oxygen deprivation conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:865–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duggan DE, Wechsler JA. 1973. An assay for transaminase B enzyme activity in Escherichia coli K-12. Anal. Biochem. 51:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGilvray D, Umbarger HE. 1974. Regulation of transaminase C synthesis in Escherichia coli: conditional leucine auxotrophy. J. Bacteriol. 120:715–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook SP, Galve-Roperh I, Martínez del Pozo A, Rodríguez-Crespo I. 2002. Direct calcium binding results in activation of brain serine racemase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27782–27792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Felice M, Squires C, Levinthal M, Guardiola J, Lamberti A, Iaccarino M. 1977. Growth inhibition of Escherichia coli K-12 by l-valine: a consequence of a regulatory pattern. Mol. Gen. Genet. 156:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Felice M, Squires C, Levinthal M. 1978. A comparative study of the acetohydroxy acid synthase isoenzymes of Escherichia coli K-12. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 541:9–17 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JH, Herring PA, Patterson EB, Blatt JM. 1993. A mechanism for valine-resistant growth of Escherichia coli K-12 supported by the valine-sensitive acetohydroxy acid synthase IV activity from ilvJ662. Biochimie 75:759–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freundlich M, Clarke LP. 1968. Control of isoleucine, valine and leucine biosynthesis. V. Dual effect of alpha-aminobutyric acid on repression and end product inhibition in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 170:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaRossa RA, Van Dyk TK, Smulski DR. 1987. Toxic accumulation of alpha-ketobutyrate caused by inhibition of the branched-chain amino acid biosynthetic enzyme acetolactate synthase in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 169:1372–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw KJ, Berg CM. 1980. Substrate channeling: alpha-ketobutyrate inhibition of acetohydroxy acid synthase in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 143:1509–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soda K, Yoshimura T, Esaki N. 2001. Stereospecificity for the hydrogen transfer of pyridoxal enzyme reactions. Chem. Rec. 1:373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw JP, Petsko GA, Ringe D. 1997. Determination of the structure of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus at 1.9-A resolution. Biochemistry 36:1329–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe A, Yoshimura T, Mikami B, Esaki N. 1999. Tyrosine 265 of alanine racemase serves as a base abstracting alpha-hydrogen from l-alanine: the counterpart residue to lysine 39 specific to D-alanine. J. Biochem. 126:781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe A, Yoshimura T, Mikami B, Hayashi H, Kagamiyama H, Esaki N. 2002. Reaction mechanism of alanine racemase from Bacillus stearothermophilus: x-ray crystallographic studies of the enzyme bound with N-(5′-phosphopyridoxyl)alanine. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19166–19172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto M, Yamauchi T, Kamiya N, Miyahara I, Yoshimura T, Mihara H, Kurihara T, Hirotsu K, Esaki N. 2009. Crystal structure of a homolog of mammalian serine racemase from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 284:25944–25952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kisumi M, Komatsubara S, Chibata I. 1971. Valine accumulation by alpha-aminobutyric acid-resistant mutants of Serratia marcescens. J. Bacteriol. 106:493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blombach B, Schreiner ME, Holátko J, Bartek T, Oldiges M, Eikmanns BJ. 2007. L-valine production with pyruvate dehydrogenase complex-deficient Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2079–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valle J, Da Re S, Schmid S, Skurnik D, D'Ari R, Ghigo JM. 2008. The amino acid valine is secreted in continuous-flow bacterial biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 190:264–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radmacher E, Vaitsikova A, Burger U, Krumbach K, Sahm H, Eggeling L. 2002. Linking central metabolism with increased pathway flux: L-valine accumulation by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2246–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powers SG, Snell EE. 1976. Ketopantoate hydroxymethyltransferase. II. Physical, catalytic, and regulatory properties. J. Biol. Chem. 251:3786–3793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Primerano DA, Burns RO. 1982. Metabolic basis for the isoleucine, pantothenate or methionine requirement of ilvG strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 150:1202–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniel J, Dondon L, Danchin A. 1983. 2-Ketobutyrate: a putative alarmone of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 190:452–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]